Tick bites, IgE to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose and urticarial or anaphylactic reactions to mammalian meat: The alpha-gal syndrome

Abstract

The recent recognition of a syndrome of tick-acquired mammalian meat allergy has transformed the previously held view that mammalian meat is an uncommon allergen. The syndrome, mediated by IgE antibodies against the oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), can also involve reactions to visceral organs, dairy, gelatin and other products, including medications sourced from non-primate mammals. Thus, fittingly, this allergic disorder is now called the alpha-gal syndrome (AGS). The syndrome is strikingly regional, reflecting the important role of tick bites in sensitization, and is more common in demographic groups at risk of tick exposure. Reactions in AGS are delayed, often by 2–6 h after ingestion of mammalian meat. In addition to classic allergic symptomatology such as urticaria and anaphylaxis, AGS is increasingly recognized as a cause of isolated gastrointestinal morbidity and alpha-gal sensitization has also been linked with cardiovascular disease. The unusual link with tick bites may be explained by the fact that allergic cells and mediators are mobilized to the site of tick bites and play a role in resistance against ticks and tick-borne infections. IgE directed to alpha-gal is likely an incidental consequence of what is otherwise an adaptive immune strategy for host defense against endo- and ectoparasites, including ticks.

Abbreviations

-

- AGS

-

- alpha-gal syndrome

-

- Alpha-gal

-

- galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose

-

- IgA

-

- immunoglobulin A

-

- IgE

-

- immunoglobulin E

-

- IgG

-

- immunoglobulin G

-

- IgM

-

- immunoglobulin M

-

- LDL

-

- low-density lipoprotein particle

-

- TLR

-

- toll-like receptor

-

- VLDL

-

- very low-density lipoprotein particle

1 INTRODUCTION

BOX 1. Major milestone discoveries

- Investigations into first infusion anaphylaxis to cetuximab leads to the recognition of IgE to alpha-gal in a region of the southeastern USA

- Reports of tick-acquired allergic reactions to mammalian meat in Australia and recognition that cases of adult-onset mammalian meat allergy in the southeastern USA were associated with IgE to alpha-gal

- Confirmation of link between alpha-gal IgE sensitization and tick bites

The original description of the alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), a tick-acquired mammalian meat allergy caused by IgE to the oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), only dates back some 15 years.1, 2 The prevalence of AGS prior to that time can be debated, but what is indisputable is that several unusual features contributed to a lack of earlier recognition of the syndrome. Whereas traditional IgE-mediated food allergy, such as in children who are allergic to peanut or tree nuts, involves rapid onset of reactions after consumption of a relevant allergen, reactions in AGS characteristically start between 2–6 h after meat ingestion.3 This delay in symptom onset, often among adults who had tolerated mammalian meat for many years, led to confusion for both patients and providers in connecting an allergic reaction with a meal that could have been consumed 5 h earlier. Another unique feature that hindered earlier description of the syndrome relates to the fact that AGS, owing to the role of bites from certain tick species in sensitization, is strikingly regional.4 Taken together, it was a confluence of events including those unrelated to mammalian meat allergy that paved the way for the seminal publications describing what we now call the alpha-gal syndrome5, 6 (see Box 1). These events included: (i) recognition that IgE antibodies specific for alpha-gal were present in individuals who experienced anaphylaxis on first infusion of the novel cancer monoclonal antibody cetuximab,7, 8 (ii) reports of patients who experienced frequent tick bites and developed mammalian meat allergy,1, 9, 10 (iii) the presence of an oligosaccharide on cat IgA that was recognized by IgE in some individuals who were not symptomatically allergic to cat,11, 12 and (iv) patients in Europe who were allergic to kidneys and other organs from pigs.13 Here we review current understanding and epidemiology of AGS and discuss recent insights into the relevance of tick bites in the development of IgE and allergic immune responses.

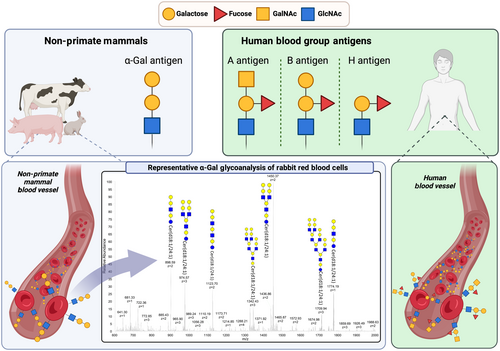

2 WHAT IS ALPHA-GAL?

The oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, though only recently appreciated by the allergy/immunology community as an important allergen, has been the subject of study for nearly a century. The initial description likely dates back to work by Landsteiner and Miller in 1925 who described a ‘B-like’ blood group antigen on the blood cells of New World Monkeys that was targeted by an ‘agglutinin’ in human serum.14, 15 Through the seminal work of Galili and others that started in the 1980s, it is now evident that: (i) this antigen was alpha-gal,15 (ii) alpha-gal is expressed widely not only by non-primate mammals but also by select bacteria and parasites, including ticks (see Table 1),16-36 (iii) alpha-gal can be expressed as part of glycoproteins or glycolipids37 and (iv) humans universally make abundant IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies targeting alpha-gal.38-40 Although often referred to by the simple disaccharide Gal-α-1,3-Gal structure, it is helpful to realize that literature describing the trisaccharide Gal-α-1,3-Gal-β-1,4-GlcNAc also refers to alpha-gal. Modern structural studies have revealed that alpha-gal differs from the B-group blood antigen by a single fucose at the penultimate galactose residue (see Figure 1) and serologic studies show cross-reactivity in antibody binding between the two oligosaccharides.41-43 As discussed later, this likely explains why the ABO-blood group, specifically the expression of the B-blood group, impacts AGS risk. Given the abundance of alpha-gal-specific IgG and IgM produced by all humans, it is also not surprising that alpha-gal is recognized as a major barrier to xenotransplantation.44, 45 As a consequence, alpha-gal has now been targeted by biotechnology companies and ‘alpha-gal knock-out’ swine (e.g. GalSafe pigs from Revivicor, Inc.) have been engineered with hopes of overcoming this barrier.46, 47

| Organism | References |

|---|---|

| Mammals | |

| Non-primate mammals, platyrrhines and prosimians | Macher et al, 2008 |

| Ticks | |

| Amblyomma americanum | Crispell et al, 2019; Choudhary et al, 2021; Sharma et al, 2021 |

| Amblyomma cajennense | Araujo et al, 2016 |

| Amblyomma hebraeum | Murangi et al, 2021 |

| Haemaphysalis longicornis | Chinuki et al, 2016 |

| Hyaloma marginatum | Mateos-Hernandez et al, 2017 |

| Ixodes ricinus | Hamsten et al, 2013; Hamsten et al, 2013; Fischer et al, 2020 |

| Rhipicephalus evertsi | Murangi et al, 2021 |

| Rhipicephalus bursi | Mateos-Hernandez et al, 2017 |

| Endoparasite | |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | Murangi et al, 2022 |

| Plasmodium subspecies | Yilmaz et al, 2014 |

| Leishmania | Avila et al, 1989; Moura et al, 2017 |

| Schistosoma mansoni | Hodzic et al, 2020 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Hodzic et al, 2020; Mateos-Hernandez et al, 2020 |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | Avila et al,1989; Almeida et al,1994 |

| Bacteria | |

| E. coli | Galili et al,1988; Yilmaz et al, 2014 |

| Serratia | Galili et al, 1988 |

| Salmonella | Galili et al, 1988 |

| Klebsiella | Galili et al, 1988 |

| Mycobacterium spp | Cabezas-Cruz et al, 2017 |

| Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli, H. influenza, Lactobacillus species) | Montassier et al, 2020 |

| L. mesenteroides | Bamgbose et al, 2022 |

| L. brevis | Bamgbose et al, 2022 |

| A. omposti | Bamgbose et al, 2022 |

An evolutionary lens raises important questions about the variance in alpha-gal expression across different species. In mammals, alpha-gal synthesis depends on the glycosylation enzyme α-1,3-galactosyltransferase. The gene encoding this enzyme is present in humans and higher primates, but, owing to select mutations, the gene is not functionally expressed and is considered a pseudogene. In humans, this can be attributed to at least two separate mutations that have been selected over the past ~28 million years.48, 49 The explanation for the retention of these mutations is not entirely clear, but the universal lack of functional alpha-gal expression in humans and other higher primate species clearly suggests a strong selective advantage.49, 50 Some have argued that the loss of alpha-gal expression and subsequent development of anti-Gal antibodies in higher primates conferred protection against enveloped zoonotic viruses or parasites that carried the glycan.51 However, alternative explanations are also possible. A recent study suggests a mechanism unrelated to alpha-gal-specific immunity in which loss of alpha-gal glycosylation on IgG contributed to enhanced IgG effector function.52

3 EPIDEMIOLOGY, RELATIONSHIP TO TICKS AND OTHER RISK FACTORS

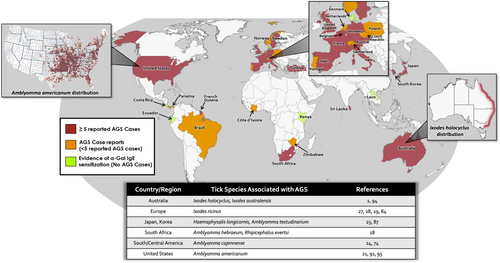

AGS is reported in many areas around the globe (Figure 2),4, 13, 25, 53-81 but firm estimates of prevalence and incidence are difficult. Challenges in describing the epidemiology stem from the fact that AGS (i) is not a reportable disease, (ii) does not have a dedicated diagnostic medical billing code (at least in the USA), (iii) has marked regional variability and (iv) the alpha-gal sIgE test may also be costly for some patients, leading to underdiagnosis. Population-based serologic surveys are informative, but on the other hand, we now appreciate that many individuals who have alpha-gal specific IgE are not aware of symptoms. Our understanding of the distribution of AGS cases comes from several pieces of evidence, not excluding social media platforms (see ZeeMaps.com, where in the world is alpha-gal?). To better understand regional variance it is also important to appreciate that bites from certain species of ticks are critical in driving sensitization. The evidence supporting a role for ticks is now unequivocal (see Box 2), with different species of ticks being implicated in specific regions where AGS is reported (Table 1 and Figure 2).10, 21, 22, 24, 27, 28, 57, 82-95

BOX 2. Evidence that ticks are causally related to AGS

- Tick bites, especially those that are pruritic, are strongly associated with AGS and alpha-gal IgE is directly associated with number of prior tick bites

- Regional variability in AGS corresponds with the territory of certain tick populations

- Levels of alpha-gal IgE are directly related to frequency of tick bites

- A small number of cases followed prospectively following tick bites

- Data showing that alpha-gal IgE wanes in patients who avoid tick bites, but not in patients who experience subsequent tick bites

- Several species of ticks that are linked to AGS can express alpha-gal glycans

- Inoculation of tick extracts into mice through the skin promotes total and alpha-gal specific IgE; these mice subsequently have anaphylaxis when fed mammalian meat

In the USA, AGS cases are strongly linked with bites from A. americanum (lone star tick), and accordingly cases and alpha-gal sensitization are most prevalent in parts of the Southeast and Coastal Atlantic, including the states of Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Virginia where lone star ticks are common.4, 95 Occasional cases are reported in more northern areas, including the upper Midwest in the region of northern Minnesota.4, 96 A study by Binder et al. that investigated alpha-gal IgE blood tests in the US that were sent to a central laboratory found a similar statewide distribution and reported ~2–5 cases per 100,000 persons in the Southeast and Coastal Atlantic areas, though methodologic limitations may have led to an underestimate of true prevalence in these areas.81 A recent report looked more granularly at this data using county-based mapping and found a similar distribution pattern and estimated there have been up to 450,000 AGS cases in the USA.97 In Australia, AGS is largely restricted to an area of the eastern coast where Ixodes holocyclus ticks are established, ranging from southern New South Wales northward into Queensland.78 Of note. over 60% of the Australian population lives in this range. AGS has been described in several areas of continental Europe, largely in areas where the tick Ixodes ricinus is established.98 The largest European cohorts have been described in Sweden and Germany, but reports have ranged from Portugal eastward to Poland and Turkey.54, 58, 61, 62, 80 In Asia, AGS cases are best described in Japan, but cases have been described in South Korea and alpha-gal IgE was common among snakebite victims studied in Laos.25, 71, 78, 88 In Africa, an important study by Mabelane et al. provided evidence of challenge-proven AGS in residents of the Eastern Cape of South Africa.55 Other rare reports have come from Africa,67 and limited serological surveys have shown a strikingly high prevalence of alpha-gal IgE in some rural areas of the continent.12, 19, 79 There have been few published reports of AGS in Central and South America, but cases have been reported in Panama, Brazil and French Guiana.60, 74, 99 A serologic survey of children in tropical Ecuador reported a high prevalence of alpha-gal IgE.19 In addition, Amblyomma sculptum, a tick common in Brazil and other parts of South America, has been convincingly shown to express alpha-gal.24, 100

Risk factors other than tick bites have been reported by some groups to be associated with alpha-gal sensitization and AGS. Arguably the best studied risk factor relates to ABO blood group status as multiple studies have shown that individuals with B antigen blood group have some protection against sensitization and/or development of the clinical syndrome.42, 101 On the other hand, individuals with B blood group can still develop AGS.102 Male sex, rural residence and outdoor lifestyle have been associated with AGS, though these are presumably risk modifiers for tick exposure.4, 89, 92, 103 Cat ownership has been proposed as a possible risk factor for alpha-gal sensitization,68 but this has not been supported by other studies.4, 104 The relevance of pre-existing atopy as a risk factor for AGS remains unclear. Investigating a large Swedish cohort, Kiewet et al. reported that AGS patients had a higher frequency of IgE to common respiratory allergens than the general Swedish population.54 The authors also found that atopic AGS patients were more likely to present with anaphylaxis involving airway symptoms. However, a study of 261 cases of mammalian meat allergy in the United States found similar self-reported symptoms among individuals with and without IgE to respiratory allergens.102 Studying the Stockholm-based BAMSE birth cohort at age 24, Westman et el. found that allergen poly-sensitization was associated with alpha-gal sensitization even when accounting for tick bite history.92 In considering the relationship between pre-existing atopy and AGS it is important to recognize that total IgE levels are consistently found to be higher when comparing alpha-gal sensitized cohorts to those that are non-sensitized.89, 104, 105 While this high total IgE could be a non-specific marker of atopy, as discussed later, total IgE could equally be a direct consequence of tick bites. Finally, parasites other than ticks likely contribute to alpha-gal IgE sensitization in less developed areas of the world, with Ascaris being the best studied.18, 19 Whether this is a significant cause of symptomatic AGS remains to be demonstrated. Associations between IgE to alpha-gal and IgE to venom from stinging insects such as honey bees and wasps have been reported.102, 106 This could reflect a shared environmental sensitization risk from outdoor exposure, but a recent paper noted cross-reactivity between tick and wasp proteins.107

4 CLINICAL SPECTRUM OF IGE TO ALPHA-GAL: ASYMPTOMATIC TO LIFE-THREATENING ANAPHYLAXIS

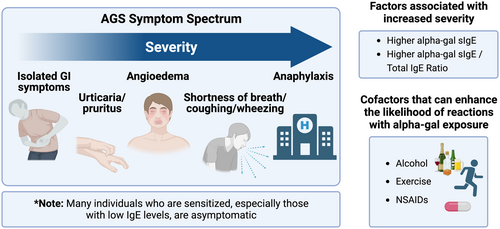

The initial description of AGS stemmed from investigation into patients suffering clear anaphylactic reactions. Reactions to cetuximab were often severe, as were the initial case series of patients reacting to mammalian meat, which explains why the syndrome was often referred to as ‘delayed anaphylaxis to red meat’.2, 7-9 We continue to see patients who have severe allergic reactions to mammalian meat, but equally, now appreciate a much greater spectrum of clinical heterogeneity (see Figure 3). In addition to inter-patient variability in symptoms, there can also be significant variability in reaction severity within a given individual. Urticaria and gastrointestinal symptoms are often reported in AGS patients, typically occurring 2–6 h after a relevant exposure.54, 102, 108, 109 Some patients deny frank hives but develop skin pruritus with flushing-like presentation or pruritus in the absence of any visible rash. Symptoms for some patients tend to involve only one system but can present as a combination.110 Recent reports emphasize that many patients with AGS, including children, can have isolated gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.111-115 These reports are also interesting as they raise the possibility that alpha-gal sensitization could be an underappreciated contributor to GI morbidity in areas where ticks are endemic.116

Not all individuals who are sensitized to alpha-gal experience allergic reactions. One of the earliest studies that convincingly showed that many individuals who were sensitized could nonetheless tolerate mammalian meat was an investigation by Fischer et al. involving Forest Workers from Southwest Germany. This cohort, which was high risk on the basis of recurrent tick exposures, had an alpha-gal IgE prevalence of 35% (at a cut-off of ≥0.1 kUA/L), but over 90% of the sensitized workers routinely consumed mammalian meat without overt allergic symptoms.104 Subsequent studies of alpha-gal sensitization in individuals not recruited on the basis of meat allergy have shown similar findings.92, 117, 118 A recent paper by McGill and colleagues assessed GI symptoms among sensitized subjects in an endoscopy screening cohort and found that most routinely consumed mammalian meat regardless of sensitization status.118

An additional consideration is whether alpha-gal IgE could contribute to symptoms or diseases not traditionally considered to be allergic. Limited evidence suggests alpha-gal IgE could contribute to arthralgia,119 which is plausible given that mast cells are present in joint synovium, but this connection certainly requires more study.120 There are also reported connections between IgE (and other isotypes of antibodies) to alpha-gal and cardiac disease. There are several different types of studies that have identified connections between antibodies specific for alpha-gal and cardiac disease. In 2005, Dr. Ankersmit in Vienna reported that lgG to alpha-gal increased after transplantation of porcine or bovine heart valves.121 That study was carried out because there was accepted evidence that implantation of valves derived from mammals increased the risk of cardiac-related mortality as compared to mechanical valves, especially in patients under age 55.122 After the discovery of lgE to alpha-gal in 2008, two separate phenomena were reported in Virginia on the consequences of implanting biovalves in a patient with lgE to alpha-gal. Our group reported three subjects who experienced hives or anaphylaxis during the first few hours after implantation and, in addition, cases of accelerated valve damage were reported in patients with IgE to alpha-gal.123, 124 The investigation into alpha-gal IgE and atherosclerosis was prompted by observations in the clinic of several AGS patients suffering myocardial infarction. In Virginia, we started a collaboration with Dr. McNamara and Dr. Taylor who had an ongoing study using high-sensitivity intra-vascular ultrasound (IVUS) to study the severity of atherosclerosis. Assaying lgE to alpha-gal in that cohort of 118 at-risk adults we found an increased risk of atherosclerotic plaques, including plaques with unstable characteristics, among patients with positive serum lgE to alpha-gal.105 Recently, a similar finding was reported in Sydney, Australia among 1056 patients who were being investigated for atherosclerosis using CT imaging of the coronary arteries.125 We have added a questionnaire on diet and allergic reactions to the prospective recruitment of at-risk patients in Virginia and confirmed that it is common for sensitized subjects to routinely consume mammalian meat and dairy.126 A causal relationship with atherosclerosis remains to be established but our working hypothesis is that subclinical inflammation in the vessel wall results from an interaction between a specific immune response to alpha-gal and routine ingestion of the allergen as part of the Western diet.127 Further studies are needed to clarify the magnitude of risk, determine whether dietary avoidance mitigates the risk and also to investigate whether sensitization could confer the risk of other subclinical chronic inflammatory diseases. Most recently, two other reports from Vienna have added a further possible direction to studying the cardiac effects of antibodies to alpha-gal. In a survey of outcome results on all cardiac valve operations in Austria, Dr. Ankersmit and his colleagues confirmed that the mortality risk among patients receiving bovine or porcine valves was higher than for those receiving mechanical valves.122 Secondly, his group published a report on increases in antibodies to alpha-gal, most strikingly IgG3, over the 3 months after implanting bovine or porcine valves.128

5 PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

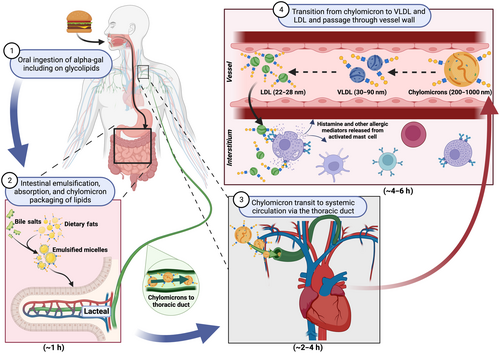

There are two novel features of the delayed allergic reactions that follow eating mammalian meat in patients with AGS. The first is that, in almost all cases, the patients are not aware of oral or other symptoms during the first 2 h. This is equally true of patients with high levels of lgE to alpha-gal and was a major reason why the syndrome was so difficult to identify clinically before the IgE assay was developed.8 The second is that severe reactions can develop rapidly after a delay of 3–5 h. There are several theories to explain the delayed responses, of which the theory about lipid particles is most compelling; however, that theory is difficult to investigate in humans and has not been proven. The attractive feature of this ‘glycolipid hypothesis’ is the well-established time taken to digest lipid particles which includes the slow passage of chylomicrons through the lymphatics in the small intestines, the thoracic duct and into the bloodstream, as well as the subsequent progressive transition to VLDL and LDL129, 130 (Figure 4). What is certain is that LDL (and HDL) are small enough to pass through the walls of small blood vessels and thus potentially bring the glycolipids close to the mast cells in the tissue. Thus, the time course could fit with the time before developing hives or abdominal symptoms. Equally, given that LDL, especially oxidized forms, penetrate vascular endothelium and enter the subintima, this could theoretically contribute to coronary atherosclerosis over a period of years.131 An important feature of the hypothesis is that the small particles, that is, LDL, are assumed to carry multiple epitopes of alpha-gal in order to be able to crosslink IgE on the FcεR1 on mast cells in the skin or blood vessels. In vitro studies support the idea that alpha-gal glycolipids, but not glycoproteins, can transit through the gut epithelium and be packaged into chylomicrons.132 However, experiments to date have not shown that LDL particles carry the oligosaccharide on them, nor has the hypothesis been demonstrated in vivo. The alternative explanation is that orally ingested glycoprotein forms of alpha-gal, which clearly can be allergenic in vitro and in vivo when introduced parenterally, are absorbed, processed and presented to IgE-bound mast cells with a delay of 3–5 h.37 This is clearly different from classic IgE-mediated food allergy, such as peanut allergy, but has parallels with some forms of wheat allergy, where co-factors are important and there is often a substantial delay between ingestion and symptom onset.133 Whether the relevant source of alpha-gal is in glycolipid and/or glycoprotein form, there is now good in vivo evidence that peak levels of alpha-gal require two or more hours to reach the systemic circulation after challenge with a mammalian meal.134 The recent development of models of semi-humanized pigs (i.e. alpha-gal knock-out pigs) both in the US and in Europe, may be the most promising approach to studying the time course of reactions after challenge.

6 DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

In areas where ticks are endemic, AGS should be in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with recurrent episodes of urticaria or anaphylaxis. We find that querying about tick bite history, particularly recent pruritic tick bites, has a high pre-clinical probability for predicting alpha-gal sensitization.4, 10, 89 Sensitization is most often identified by measuring alpha-gal specific IgE in serum, though skin tests using beef, pork or milk extracts can be helpful for clarifying or confirming the diagnosis. Testing for IgE to beef, pork or lamb is not necessary if the pre-clinical probability for AGS is high, however, these tests can be helpful for diagnosing other forms of mammalian meat allergy if alpha-gal IgE is not detected. For example, cases of pork-cat syndrome are occasionally seen in individuals who are cat allergic and react predominantly to pork.135 However, this is because of cross-reactivity between cat serum albumin and pork serum albumin and is not related to alpha-gal. Of note, commercial prick tests have limited sensitivity and intradermal tests or prick-to-prick testing using fresh meat are often required. Some groups also report using cetuximab as part of skin testing protocols.136 Basophil activation tests have been described for alpha-gal, but we are unaware that these are available for routine clinical care.137 Consistent with other IgE-mediated food allergies, there is no specific alpha-gal IgE cut-off that has both high sensitivity and high specificity for predicting clinical allergy. Mabelane et al. suggested that an alpha-gal level of 2 IU/mL had the best performance characteristics for predicting reactions while a recent report by Kersh et al. suggested 0.59 IU/mL was optimal.55, 89 The different results between the two groups are likely attributable to differences in the populations studied, but from an individual patient's perspective, it has to be emphasized that any positive test in the setting of the appropriate clinical history is suggestive of the syndrome. We have seen many AGS cases in Virginia that have had alpha-gal IgE levels <1.0 IU/mL, but whose specific/total ratio was nonetheless >1% because their total IgE was modest. To formalize the diagnosis it is also important that the presenting allergic symptoms remit or diminish on a mammalian avoidance diet. The core of management of symptomatic AGS involves avoidance of mammalian meat (and visceral organs), but some patients also need to avoid dairy products and mammalian-derived gelatin. Details about alpha-gal content in different dairy products are limited but high-fat dairy may be more problematic than light milk.138 On the other hand, whey proteins such as lactoferrin, gamma-globulin and lactoperoxidase have been shown to carry alpha-gal.139 The monoclonal antibody cetuximab has significant amounts of alpha-gal and should be avoided by all patients unless under the care of an allergist. Gelatin-containing colloidal fluids are also high-risk in AGS patients, though fluids of this kind are no longer used in most countries. Other medications such as pancreatic enzyme replacement (which is typically porcine derived) and anti-venom also often contain alpha-gal,140-144 but these can generally be tolerated or at least do not have good data linking them with severe allergic reactions.71, 142 Heparin does not intrinsically have alpha-gal linkages, but because heparin is sourced from swine intestines contamination with alpha-gal is possible. Reactions to heparin appear to be rare in most AGS patients,145 but patients who have received high-dose intravenous heparin (such as is often used during cardiovascular surgery) were reported to have a disproportionately high occurrence of anaphylaxis.146 Whether excipients such as magnesium stearate or compounds such as carrageenan contain appreciable amounts of alpha-gal is controversial and inadequately studied, but our experience is that only a small minority of AGS patients report overt allergic reactions to these products.109, 147

In patients whose symptoms do not readily respond to an avoidance diet, there are a few important considerations. One is that there could be sources of dietary alpha-gal that have not been eliminated and that a more complete avoidance strategy would be beneficial. The second is that alpha-gal is either not contributing to their symptomatology or that there could be a concurrent allergic cause in addition to AGS. Further study is needed, but there are ample examples from clinical experience of patients who experienced tick bites (in some cases clearly developing allergic reactivity to mammalian meat) who have gone on to develop symptoms suggestive of chronic spontaneous urticaria or other mast cell disorders showing some features of mast cell activation syndrome.109, 148 In those patients, emphasis should be on utilizing standard allergy medications, including H1 blockers, mast cell stabilizers such as cromolyn, or leukotriene receptor antagonists. In refractory cases who meet eligibility, treatment with the anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab may be beneficial.149 Whether biologics such as omalizumab would be beneficial for AGS patients who present with classical symptoms remains to be investigated or reported. However, given the presumptive role of IgE in mediating reactions to alpha-gal, omalizumab could be protective for AGS patients.150 In addition, dupilumab, which targets the IL-4Rα, has been shown to strikingly decrease food-specific IgE levels.151 Formal studies, ideally involving placebo-controlled trials, will be important to determine the relevance of biologics to AGS management. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is being increasingly implemented as a means of inducing food-specific tolerance (or sustained unresponsiveness) in food allergic patients.152 Many of the studies have been in children, but OIT also shows promise in adults.153 A few case reports have suggested OIT may be safe and effective in AGS, which is supported by a recently published series of 12 cases that underwent successful OIT.154-156

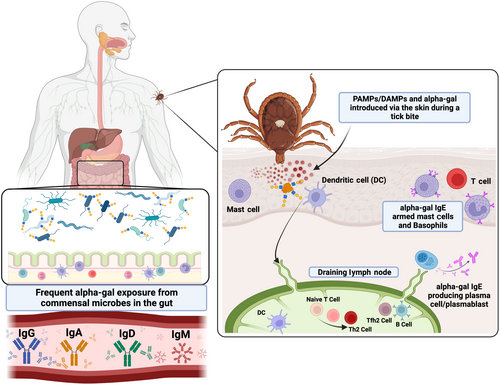

7 MECHANISMS OF ALPHA-GAL SENSITIZATION: RELEVANCE OF TICKS TO AGS AND ALLERGIC IMMUNITY

The evidence linking tick bites to alpha-gal IgE is now very strong (Box 2). In addition to the epidemiological correlations noted previously, case series have shown that alpha-gal IgE levels are higher in individuals who report frequent tick bites and alpha-gal IgE levels are more likely to wane in AGS patients who avoid recurrent tick bites.86, 87 Some of the strongest evidence comes from studies using alpha-gal ‘knock-out’ mice where tick bites or inoculation of tick extracts through the skin can lead to alpha-gal IgE induction.22, 24, 82 Importantly, the evidence does not support a role for tick-borne infections in sensitization. The explanation for why the host immune response is directed at alpha-gal makes sense in view of several studies showing that alpha-gal is expressed in the saliva of tick species that are linked with AGS.21, 29, 84, 157, 158 The question that remains to be answered is why ticks are so effective at eliciting IgE. Exposure to alpha-gal via the gut, likely from the microbiome, drives IgG, IgM and IgA in most individuals, but this is clearly not adequate for promoting IgE to alpha-gal. This suggests that there is something unique either about transmission via the skin and/or that there is another feature of tick saliva that favours the IgE class switch (see Figure 5). The idea that tick bites would be efficient at promoting alpha-gal IgE becomes perhaps less surprising when reflecting on the key role of Type 2 immune cells and mediators in defending mammalian hosts against ticks. Basophils in particular, but also eosinophils, IgE, histamine and mast cells all have roles in what has been termed ‘acquired tick resistance’.159 Best described in guinea pig models but also studied in mice and cattle, it is clear that a primary tick infestation elicits an immune response that can diminish the success of a subsequent tick infestation, including the transmission of tick-borne pathogens.160 Looking into molecular pathways relevant to IgE induction, Chandrasekhar et al. reported that subcutaneous inoculation of larval stage lone star tick extracts into mice promoted IgE class switch that depended on MyD88 signalling in B cells.82 A role for TLR2, TLR4 or TLR5 activity in this pathway was suggested by a TLR ligand screen of the tick extracts. Interestingly, when introduced intraperitoneally the same extracts did not induce IgE, indicating that exposure via the skin is also important. In accordance with the induction of IgE as part of anti-tick defense, anaphylaxis to ticks has been occasionally reported. Cases seem more common in Australia than elsewhere, perhaps indicating specific features of the Ixodes holocyclus tick, but cases have also occasionally been reported in the USA, Europe and Asia.53 A species of soft tick called Argas reflexus has also been implicated in anaphylaxis following bites, but we are unaware of any connections between this tick (or other soft ticks) and AGS.161

8 CONCLUSION

Looking back since the initial recognition of IgE to alpha-gal, our understanding of the tick-acquired mammalian meat allergy, now widely known as the alpha-gal syndrome (AGS), has come a long way. Important studies have come from meat-allergic patients, non-allergic populations, mouse models and from ticks. Early insights about the delayed timing of onset and relationship to ticks reported in Australia and the United States have been replicated and confirmed by several groups, including in Europe, Japan and South Africa, and we are increasingly aware that the syndrome can often present with isolated gastrointestinal symptoms. Realization that a large proportion of individuals sensitized to alpha-gal are not aware of symptoms has also opened up the possibility that IgE to this blood-group-like antigen of non-primate mammals may be a risk factor for chronic inflammatory disorders such as coronary artery disease. A causal role for tick bites in the development of mammalian meat allergy may not have always been readily apparent, but appreciation of the important role of allergic immune pathways in anti-tick defense goes a long way to explaining the connection between tick bites and AGS. We expect that ongoing and future investigations in the field will reveal novel insights into allergic immunity and this unusual syndrome (Box 3).

BOX 3. Open questions for future research

- What factors at the tick–host interface drive total and alpha-gal IgE?

- What are the mechanisms that explain the delay and heterogeneity of symptoms?

- Does IgE to alpha-gal contribute to chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g. atherosclerosis)?

- Can a diet including mammalian products contribute to atherosclerosis in individuals with IgE to alpha-gal who are not aware of allergic symptoms?

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JW and TPM wrote the original manuscript, SA created graphical content and all authors provided critical feedback.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (JW, LE, SC, TP-M) and AAAAI Faculty Development Award (JW).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

TP-M receives royalties for a patent related to the alpha-gal IgE assay. J.W. and TP-M have received assay support from Thermo-Fisher/Phadia. S.C. is the recipient of a grant from Revivicor, Inc. and has received royalties from UpToDate Inc., honoraria from Genentech for participation in educational events and Regeneron for participation in an advisory meeting. The remaining authors do not have relevant disclosures.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.