2019 ARIA Care pathways for allergen immunotherapy

Abstract

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is a proven therapeutic option for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and/or asthma. Many guidelines or national practice guidelines have been produced but the evidence-based method varies, many are complex and none propose care pathways. This paper reviews care pathways for AIT using strict criteria and provides simple recommendations that can be used by all stakeholders including healthcare professionals. The decision to prescribe AIT for the patient should be individualized and based on the relevance of the allergens, the persistence of symptoms despite appropriate medications according to guidelines as well as the availability of good-quality and efficacious extracts. Allergen extracts cannot be regarded as generics. Immunotherapy is selected by specialists for stratified patients. There are no currently available validated biomarkers that can predict AIT success. In adolescents and adults, AIT should be reserved for patients with moderate/severe rhinitis or for those with moderate asthma who, despite appropriate pharmacotherapy and adherence, continue to exhibit exacerbations that appear to be related to allergen exposure, except in some specific cases. Immunotherapy may be even more advantageous in patients with multimorbidity. In children, AIT may prevent asthma onset in patients with rhinitis. mHealth tools are promising for the stratification and follow-up of patients.

Abbreviations

-

- AIT

-

- allergen immunotherapy

-

- AR

-

- allergic rhinitis

-

- ARIA

-

- Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma

-

- CDSS

-

- clinical decision support system

-

- CRD

-

- chronic respiratory disease

-

- DB-PC-RCT

-

- double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial

-

- EIP on AHA

-

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing

-

- EIT

-

- European Institute for Innovation and Technology

-

- EU

-

- European Union

-

- GRADE

-

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

-

- ICER

-

- incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

-

- ICP

-

- integrated care pathway

-

- JA-CHRODIS

-

- Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle

-

- MACVIA

-

- fighting chronic diseases for active and healthy ageing

-

- MASK

-

- Mobile Airways Sentinel NetworK

-

- MASK-air®

-

- (formerly Allergy Diary)

-

- NICE

-

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK)

-

- PCP

-

- primary healthcare professional

-

- QALY

-

- quality-adjusted life year

-

- QOL

-

- quality of life

-

- RCT

-

- randomized controlled trial

-

- RWE

-

- real-world evidence

-

- SCIT

-

- subcutaneous immunotherapy

-

- SCUAD

-

- severe chronic upper airway disease

-

- SLIT

-

- sublingual immunotherapy

-

- SmPC

-

- summary of product characteristics

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

1 INTRODUCTION

In all societies, the burden and cost of allergic diseases are increasing rapidly and “change management” strategies are needed to support the transformation of the healthcare system for integrated care. As an example for allergic disease care, the newest ARIA (Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma) project (ARIA phase 4)1, 2 and POLLAR (Impact of Air POLLution on Asthma and Rhinitis, EIT Health)3 are proposing digitally-enabled, integrated, person-centred care for rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity embedding environmental exposure.2, 4

Integrated care pathways (ICPs) are structured multidisciplinary care plans detailing the key steps of patient care.5 They promote the translation of guideline recommendations into local protocols and their application to clinical practice.6, 7 ICPs should integrate recommendations from clinical practice guidelines, but they usually enhance recommendations by combining interventions iteratively, integrate quality assurance and offer recommendation on the coordination of care.

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is a proven therapeutic option for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and/or asthma for many standardized products by sublingual (SLIT) or subcutaneous (SCIT) routes.8-14 Studies using prescription databases have recently found that the efficacy demonstrated in double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials (DB-PC-RCT) translates into real life.15 In most countries, AIT is more expensive than other medical treatments for allergic rhinitis (AR) and should therefore be considered in patients within a stratified medicine approach.16 Many international and national guidelines on AIT 8-14, 17 have been produced but the evidence-based method varies, many are complex and none propose ICPs.

The aim of the present publication is to develop the ARIA ICPs for both SCIT and SLIT that were proposed by a EAACI Task Force.18

2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCUMENT

The original draft of this document was prepared by JB and was circulated to several authors for comments. A questionnaire (Annex 1) was also circulated, and the answers were collected.

The document and the questionnaire answers were reviewed during a meeting including ARIA, EIT Health (POLLAR: Impact of Air POLLution on Asthma and Rhinitis),3 the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing19 and the Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases (GARD, WHO Alliance) with the participation of major allergy societies and patient's organizations (Paris, December 3, 2018). The meeting was carried out with the support of many organizations (Figure 1).

The final document was approved by the members of the Paris study group and the ARIA working group.

A Pocket Guide has been developed and includes the major recommendations of this document in a simple format. It is to be used digitally and in paper form to guide clinical practice for all stakeholders including patients, all healthcare providers and policymakers.

3 GAPS IN AIT KNOWLEDGE

AIT is an effective treatment, but there are many gaps including those identified by AIRWAYS ICPs19, 20 (Table 1).21 Some of these gaps are the basis for the development of ARIA ICPs for AIT.

| Better understand the role of AIT across the life cycle, particularly in preschool children (prevention and treatment) and in the elderly |

| Increase the awareness of the impact of AIT across the life cycle to promote active and healthy ageing |

| Stratify patients who benefit the most from AIT in all age groups |

| Launch a collaboration to develop care pathways for chronic respiratory allergic diseases integrating AIT in European countries and regions within the framework of AIRWAYS ICPs |

| Follow and implement actions and plans suggested by this integrated collaboration |

| Provide evidence for regulatory decisions including cost-effectiveness |

| Follow and implement actions and plans suggested by this integrated collaboration, endorsed by national (or regional) health authorities |

| Encourage research strategies for novel approaches and biomarker discovery in AIT |

| Encourage research strategies for “responders/no-responders” in AIT |

4 ALLERGENS TO BE USED

4.1 Relevant extract

The decision to prescribe AIT for the patient should be based on allergen relevance and on the persistence of clinical symptoms, despite appropriate medications according to guidelines, as well as on the availability of good-quality extracts.

Adequate quality is essential for any medicinal product to be eligible for marketing.10, 22 Only regulated, standardized allergen extracts that are efficacious and safe should be used for AIT.23, 24

4.2 Extrapolation to untested products

AIT products have to show efficacy and safety in line with regulatory requirements.25 Allergen extracts cannot be regarded as generics. In the EU, each individual product (individual product or mixtures), with the exceptions made by EMA (European Medicines Agency) or PEI (Paul Ehrlich Institute), must prove its efficiency.23

In some cases, exceptions related to the concept of homologous groups defining allergens with a significant clinical important cross-reactivity can be accepted without specific clinical documentation. These homologous groups include a range of pollen allergen extracts and house dust mites which are defined in the respective EMA guides for allergen products.23

There is no evidence that mixing different allergens will have the same effect as separately administering individual allergens. Mixing different allergens can result in a dilutional effect—underdosing of the treatment and potential specific allergen degradation—due to the enzymatic activity of certain allergens.26 The risk of allergic side effects can increase, especially by the degradation, when a new batch is used.27 Therefore, the EMA has recommended only to use mixed allergen products of allergens represented by the allergen sources from homologous groups.23

4.3 Named patient products

In many countries, named patient products (NPP) are used by practitioners in an effort to apply precision treatment to patients. However, this practice requires appropriate confirmatory trials and real-world evidence since clinical data with some allergens cannot be directly extrapolated to NPP practice. NPPs are marketed on exception from the European legislation on allergen extracts.14, 28

4.4 Polysensitized patients

Allergic diseases are among the most complex and diverse diseases. Patients are often sensitized (IgE) to many allergens (polysensitization), but not all of these sensitizations may be clinically relevant. Therefore, it is important to treat the allergies that give rise to allergic symptoms and not the sensitizations potentially irrelevant for the patient. There is a broad range of evidence for the clinical efficacy of single extracts in polysensitized patients.29-31

Instead of mixing extracts, the different allergens can be applied separately.12 However, it has been proposed without data that two extracts can be given with a 30-minute interval in two different injection spots. By doing so, each allergen can be monitored separately for the local reaction and potential systemic side effects.

In general, the question regarding the efficacy of poly-allergen compared to oligo-allergen or mono-allergen immunotherapy in polysensitized patients has not been addressed in carefully designed clinical trials. A recent report from an NIH-sponsored international workshop on aeroallergen immunotherapy outlines trial concepts to address this important knowledge gap.32

5 STRATIFICATION OF ALLERGIC PATIENTS FOR AIT

5.1 Concept of patient stratification

Precision medicine aims to customize health care with medical decisions, practices and/or products tailored to the individual patient. It also refers to the tailoring of medical treatment to the clinical and social characteristics of each patient and not necessarily to genomics.33 The stratification of patients into subpopulations is the basis of clinical decision-making for increased diagnostic and treatment efficacy.34, 35 Patient stratification also integrates cost trends and social determinant risk models to match the patient to the right care management. This model applies to AIT.36

In non–life-threatening diseases with a very high prevalence, such as allergic diseases, patient stratification is required (a) to identify the best candidates for intervention through complex care management, (b) to reduce the amount of time and resources needed to match the right patient to a care management programme and (c) to optimize costs as some therapeutic interventions cannot be administered to all patients. Patient stratification may also help to improve the patient's engagement.37

Molecular diagnosis, when used with other tools and patients' clinical records, can help clinicians to better select the most appropriate patients and allergens for AIT38 and, in some cases, predict the risk of adverse reactions.39 The pattern of sensitization to allergens could potentially predict the efficacy of allergen immunotherapy provided that these immunotherapy products contain a sufficient amount of these allergens. Nevertheless, multiplex assay remains a third-level approach, not to be used as a screening method in current practice.39

VAS may also be useful for monitoring AIT effectiveness and medication use as it is easy to use and has been validated for AR control of severity. It has also been used as a secondary endpoint in both adult and paediatric trials.40, 41

The role of precision medicine in selecting an AIT regimen was proposed further to an expert meeting36 (Table 2).

| Precise diagnosis with history, skin prick tests and/or specific IgE and, if needed, component-resolved in vitro diagnosis (CRD).116 In some rare instances, provocation tests may be needed |

| Proven indications: Allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis and/or asthma |

| Allergic symptoms predominantly induced by the relevant allergen exposure |

| Patient stratification: Poor control of symptoms despite appropriate pharmacotherapy according to guidelines with adherence to treatment during the allergy season and/or the alteration of the natural history of allergy. Mobile technology may become of relevant importance in the stratification of patients (mHealth biomarker) |

| Demonstration of efficacy and safety for the product with relevant trials |

| The patient (and caregiver)’s views represent an essential component |

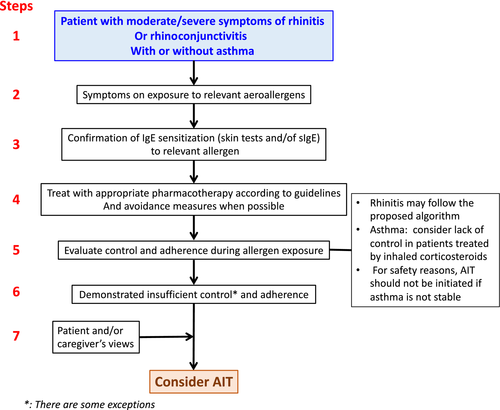

The flow of the precision medicine approach in allergic disease has been adapted (Figure 2) from (Ref.16) and(Ref.36). In some instances, AIT can be offered to patients whose AR is controlled by pharmacotherapy such as those who may develop thunderstorm-induced asthma.42, 43 AIT should also be considered even in moderate AR, particularly (but not necessarily only) in patients who have had asthma exacerbations during the pollen season and who live in geographically at-risk regions.

5.2 Biomarkers in AIT

Biomarkers - clinical or laboratory characteristics that reflect biological processes - are essential for monitoring the health of patients. They include clinical signs identified by physical examination, biological assays, mHealth outcomes, genomic indices and others that can be objectively measured and used as indicators of pathophysiological processes.44 They can be used individually or in combination, but they require further studies.

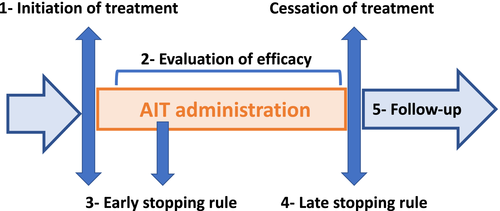

There are currently no validated genetic or blood biomarkers for predicting or monitoring the efficacy of AIT at an individual patient level although several candidates have been investigated.45 Biomarkers associated with mHealth and a clinical decision support system (CDSS)46 may change the scope of AIT as they will help monitor the patient's disease control47, 48 for (a) patient stratification, (b) clinical trials and real-world evidence, (c) monitoring efficacy and safety of targeted therapies (a critical process for identifying appropriate reimbursement) and (d) implementation of stopping rules (Figure 3). Clinical stopping rules should be developed for AIT, similarly to what is currently considered for biologics in severe asthma, as a guidance for continuing or stopping treatment after a short (early stopping rule) or long (late stopping rule) period. As an example, a global treatment evaluation after 16 weeks is used as an early stopping rule for omalizumab treatment.49, 50

5.3 ARIA

In ARIA 2008,16 it was indicated that DB-PC-RCTs have confirmed the efficacy of SCIT and SLIT. However, trial-based clinical efficacy is one of the many factors in a clinician's decision-making process for the use of AIT, especially since AIT RCTs are designed to fulfil regulatory demands for marketing authorization.51 Before starting AIT, it is essential to appreciate the relative value of pharmacotherapy and AIT as well as the degree of disease control achieved using pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, it is important to consider the rest of the patient's medical history as well as his/her social and geographical environment. The indications for SCIT in ARIA 2008 were similar to those published in 199852 and 2001.53

6 ECONOMIC BURDEN OF ALLERGIC RHINITIS AND ASTHMA, AND COST-EFFECTIVENESS OF AIT

Allergic diseases place a huge burden on society in terms of high prevalence, morbidity, direct costs (health service and drugs prescribed) and indirect costs, in particular those related to presenteeism.54 In addition, allergies have an impact on learning and performance at all levels of education.55, 56 Better care for allergies based on guideline-based treatment would allow substantial savings for Europe's economy.55

Patients with allergic diseases may not understand the benefits of treatment, and adherence to treatment is poor.47 A substantial proportion of AR patients can be managed by appropriate pharmacological treatment.1 However, a subset of patients (10% to 20%) is poorly controlled and is ascribed to SCUAD (severe chronic upper airway disease).57-59 Patients with asthma tend to incur higher rhinitis costs.

The cost-effectiveness of AIT should be considered for ICPs. However, it varies widely between countries, and in some countries such as Japan, the costs of AIT and pharmacotherapy are similar, whereas in the EU, acquisition costs of AIT are higher than pharmacotherapy. A health technology assessment examined the comparative costs of SLIT and SCIT using the UK cost model.60 A benefit from both SCIT and SLIT compared with placebo was consistently demonstrated, but the extent of this effectiveness in terms of clinical benefit was considered unclear. The study concluded that both SCIT and SLIT may be cost-effective from around six years compared with standard treatment using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000-30 000 per quality-adjusted life years (QALY).60, 61 A systematic overview showed that the cost-effectiveness of AIT is limited and of low methodological quality, but suggests that AIT may be cost-effective for people with AR with or without asthma.62 This systematic overview suggested that SLIT and SCIT would be considered cost-effective using the NICE cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000 per QALY.63 Many of these studies were based on assumptions of the preventive effect of AIT using prediction models such as Markov's model. These costs should be compared to biologics in the treatment of severe asthma. Although many limitations were identified, NICE proposed that omalizumab,64 mepolizumab65 or reslizumab66 were likely to be cost-effective in severe asthma at the threshold of £30 000 per QALY.

However, the cost model of NICE may be questioned as it was developed for diseases impairing mobility or for severe diseases and does not take indirect costs (eg presenteeism) into account. Furthermore, it neglects the potential savings outside the UK healthcare system which may not be generalizable.

7 SAFETY

7.1 Subcutaneous immunotherapy

A typical reaction (local reaction) is redness and swelling at the injection site immediately or several hours after the injection. Sometimes, sneezing, nasal congestion or hives can occur (systemic reactions).67 Serious reactions to injections are very rare but require immediate medical attention. Symptoms of an anaphylactic reaction can include swelling in the throat, wheezing or tightness in the chest, nausea and dizziness. The most serious reactions develop within 30 minutes after the injections and it is therefore recommended that patients wait in their doctor's surgery for at least 30 minutes after an injection.

7.2 Sublingual immunotherapy

Allergen drops or tablets have a more favourable safety profile than injections. SLIT can be administered at home after the first dose is administered under the supervision of a physician. The large majority of adverse events are local (mouth itching, lip swelling, nausea) and spontaneously subside after the first days of administration. The severity of local side effects is graded according to persistence and impact on the quality of life.68 In some countries outside of Europe, SLIT tablets include a warning about possible severe allergic reactions and adrenaline auto-injectors are routinely recommended. This is not the case in Europe although in the rare event that a general allergic reaction occurs after SLIT then the risk/benefit should be reassessed and a decision made whether to continue SLIT and, if appropriate, whether a rescue auto-injector should be provided.

8 PATIENT'S VIEWS

The patient's perspective should always be considered to enable a customized approach in shared decision-making. There are contrasting real-life studies assessing the level of knowledge, perceptions, expectations and satisfaction about AIT. In two European studies, there was a relatively high degree of patient's perception and satisfaction that corresponded well with the physician's views.69, 70 However, most studies report a lack of information from allergic patients and every effort should be made to improve communication, leading to increased patient knowledge and increased patient satisfaction.71, 72 Many AR patients have never heard of AIT.72

Adherence to allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is crucial for its efficacy. SCIT requires regular (often monthly) visits, while SLIT is performed with a daily intake of allergen tablets or drops at home. Nonadherence to an AIT schedule and premature discontinuation are common problems.73 Various studies have shown controversial results with regards to the rate of AIT adherence. Evidence-based communication, strategy-patient-centred care, motivational interviewing and shared decision-making all underscore the importance of taking time to establish trust, understand patient concerns and priorities, and involve the patient in decisions regarding AIT.74 A well-organized allergologist's time schedule not only increases safety but also offers the possibility of close follow-up and an increase in patient loyalty.73

Information from a medical, economical and legal perspective illustrates the importance of the effort for evidence. From the medico-legal standpoint, the application of current medical knowledge, in combination with care for the patient's welfare, should drive daily medical practice. Medical criteria need to be prioritized over economic aspects, as physicians need to choose treatments according to the commonly acknowledged professional standards. Furthermore, the physician has the obligation to inform the patient about treatment options according to professional standards - detailing routes of administration, benefits and risks of available treatments/drugs - and to involve him/her in the decision.75

9 PHARMACIST'S VIEWS

Self-medication to treat AR symptoms is common, and most patients self-manage their AR with few interactions with their physician.76 Community pharmacists are the most accessible health professionals for the public, and AR is one of the most common diseases managed by pharmacists. They play an essential role in the management of pharmacotherapy, counselling, disease prevention and primary care. In particular, with the availability of nonprescribed medications (OTC) in the pharmacy, the community pharmacy is often the first stop for AR management.77, 78

AR treatment encompasses three different aspects: avoidance of allergen exposure, pharmacotherapy and immunotherapy. The pharmacist's intervention can specifically tackle the first two and might be an opportunity for patient education in terms of avoidance of allergen exposure, disease information and medication use, especially medication administration and adherence. However, products for allergen immunotherapy are available in the pharmacies of many countries and the pharmacist must be well-informed about this treatment. Moreover, the pharmacist might play an important role in educating patients about the commitments involved in immunotherapy and its risks. For example, if patients miss several doses of immunotherapy, they may have to restart it. It is therefore important for patients to know what is expected up front and the pharmacist can play a significant role in providing this information.

10 GENERAL PRACTITIONER'S VIEWS

In many countries, the diagnosis and management of allergic disorders take place almost exclusively in primary care that has an essential role in the diagnosis and management of allergic diseases.79, 80 The continuous, easy-to-access and holistic role of primary care can support the identification of allergic patients, reassure early diagnosis and regularly follow up allergic patients for assessment of disease control, treatment adjustments and shared decision-making that is patient-centred. However, few general practitioners (GPs) receive formal undergraduate or postgraduate training in allergy.81, 82 Although considered important,80, 83, 84 there are minimal requirements for training and certification of subspecialists in allergy.85 Therefore, it is important for GPs to have access to training and evidence-based primary care allergy guidelines.86 Although some attempts of ICPs have been made,87 close collaboration with specialists for proper and time-efficient referral of cases will be beneficial for the patient and the healthcare system. Clear referral criteria and pathway plans should be created, implemented and validated by national circumstances and by cost-efficiency evaluation.88 Furthermore, GPs play a major role in patient education, self-medication and shared decision-making,34, 88, 89 borrowing good practices from the management of other chronic diseases. Greater patient adherence to AIT is reported if AIT is provided by a GP rather than a specialist.90 SCIT could also be carried out in primary care, and although it is associated with some risks, these can be minimized when given by trained GPs that carefully select patients in an appropriate environment with available primary care facilities for treating systemic anaphylactic reactions.91-94

11 PRACTICAL APPROACH FOR PATIENT STRATIFICATION IN AIT

Shared decision-making is required for AIT. Patients should be informed about all possible treatment options, benefits and drawbacks of AIT including its duration. Moreover, patients should know whether AIT is covered by their health system or insurance company and whether it will generate partial out-of-pocket costs or will need to be fully covered out-of-pocket.

Although biologics in severe asthma and AIT in allergic diseases target two different populations, costs per QALY, at least in some European countries, appear to be similar between AIT and biologics. This indicates that AIT should be reserved for stratified rhinitis patients insufficiently responsive to pharmacologic treatment (eg SCUAD57) who have been evaluated and guided with respect to adherence to pharmacotherapy. For asthma, a similar recommendation applies, but AIT should not be considered for severe asthma patients who are candidates for biologics. This recommendation is in line with the indications for a house dust mite tablet recently approved by the European Medicines Agency.95

11.1 Rhinitis and rhinoconjunctivitis in adolescents and adults

The selection of pharmacotherapy for AR patients depends on several factors, including age, predominant symptoms, severity, AR control, patient preferences and cost. Allergen exposure and resulting symptoms vary, for example based upon seasonal exposure or change in environment, making it necessary to make adjustments to therapy. CDSSs may be beneficial by assessing disease control.96 They should be based on the best evidence algorithms to aid patients and healthcare professionals to jointly decide on the treatment and its step-up or step-down strategy depending on AR control (shared decision-making).

The treatment of AR also requires consideration of (a) the phenotype (rhinitis, conjunctivitis and/or asthma) and severity of symptoms, (b) the relative efficacy of the treatment, (c) speed of onset of action of treatment, (d) current treatment, (e) historic response to treatment, (f) patient's preference, (g) interest to self-manage and (h) resource use. Guidelines and various statements by experts for AR pharmacotherapy usually propose the approach summarized in Table 3.8, 97, 98

| Overall, GRADE-based AR guidelines agree on some important points8, 97, 98, 100: |

| Oral or intra-nasal H1-anti-histamines are less effective than intra-nasal corticosteroids (INCS) for the control of all rhinitis symptoms. H1-anti-histamines are however effective in many patients with mild disease and many patients prefer oral medications to intra-nasal ones |

| Consensus has not been reached as to the relative efficacy of oral versus intra-nasal H1-anti-histamines |

| In patients with severe rhinitis, INCS represent the first line treatment. However, they need a few days to be fully effective |

| The combination of oral H1-anti-histamines and INCS does not offer a better efficacy than INCS alone 97, 98 |

| MPAzeFlu, the combined intranasal FP and Azelastine (Aze) in a single device, is more effective than monotherapy and is indicated for those patients in whom monotherapy with intranasal glucocorticoid is insufficient,117-121 patients with severe AR or those who want rapid symptom relief.97, 98, 122 An allergen chamber study has confirmed the speed of onset of the combination 101 |

All recommended medications are considered to be safe at the usual dosage except first-generation oral H1 antihistamines which should be avoided.99 Notably, despite guidelines, the practice of prescribing both an INCS and an oral H1 antihistamine is globally common.

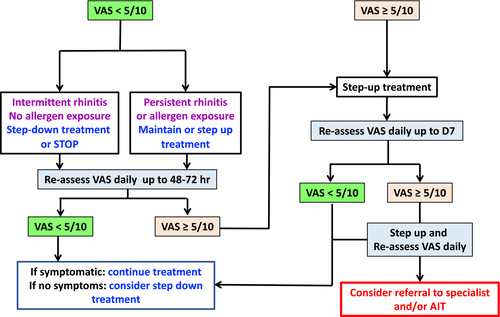

For step-up and step-down management, a simple algorithm was devised by MACVIA, but its applicability varies depending on the availability of medications and resources in different countries (Figure 4).100

Algorithms inherently result from combining individual decision nodes that represent separate recommendations. To be fully validated, the algorithm needs to be tested as a complete management plan and compared to alternative plans to explore whether the combination of these separate recommendations leads to more benefit than harm when applied in practice. A large scale mobile technology study,47 a speed of onset study101 and new recommendations all supported the algorithm.97, 98

11.2 Asthma in adolescents and adults

An algorithm is not yet available for asthma. Uncontrolled asthma is a contraindication for AIT.102

GINA (Global INitiative for Asthma) has endorsed SLIT for house dust mite asthma.103 From the SmPC for the approved SLIT house dust mite tablet,95 (a) the patient should not have had a severe asthma exacerbation within the last 3 months of AIT initiation; (b) in patients with asthma and experiencing an acute respiratory tract infection, initiation of treatment should be postponed until the infection has resolved; (c) AIT is not indicated for the treatment of acute exacerbations and patients must be informed of the need to seek medical attention immediately if their asthma deteriorates suddenly; and (d) mite AIT should initially be used as an add-on therapy to controller treatment and reduction in asthma controllers should be performed gradually under the supervision of a physician according to management guidelines.

No other AIT product has been approved for asthma in the EU.

11.3 Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity, the co-existence of more than one allergic disease in the same patient, is very common in allergic diseases, and over 85% of patients with asthma also have AR. On the other hand, only 20%-30% of patients with AR have asthma. AR multimorbidity increases the severity of asthma.104

An advantage of AIT is that it can control many aspects of multimorbidity including AR, asthma and conjunctivitis. Although multimorbid patients appear to have more severe symptoms related to each component of their allergic disease constellation, it is not yet known whether AIT is equally or more effective in these patients, compared to patients with no multimorbidity. This can be tested using existing databases, but a controlled trial will also offer useful evidence. In the conditions and authorization of a SLIT mite tablet,95 multimorbidity was recognized as an indication for mite SLIT.

11.4 Children

In children, AIT is effective as shown by RCTs105 and may have long-term effects after it is stopped.106 A recent study of SLIT,107 a previous study of subcutaneous grass pollen immunotherapy in children108 and a meta-analysis109 have provided some evidence that AIT can delay or prevent the onset of asthma in children. However, (a) the meta-analysis showed a limited reduced short-term risk of developing asthma in those with AR with unclear benefit over the longer term109 and (b) costs cannot be supported by healthcare systems due to the very large number of patients who might be treated with uncertainty on cost-effectiveness.

Thus, AIT can be initiated in children with moderate/severe AR that is not controlled by pharmacotherapy. In such children without asthma, the possibility of preventing the onset of asthma should be taken into consideration, although more studies are needed for an unreserved indication.9

The lower age for initiating AIT has not been clearly established. In many countries, products are licensed for children without a lower age limit. Prospective observational trials and/or registries can help confirm AIT safety and performance in the youngest recipients, perhaps down to the age of 3 years.

AIT is a paradigm for precision medicine, as it takes into account the multitude of sensitization and multimorbidity profile of each patient, both cross-sectionally and in relation to their natural history. Indirect yet important evidence provides clues about young patients who may benefit the most: (a) the severity of respiratory allergic disease is associated with its persistence110; (b) epitope spreading and development of new sensitizations suggest benefit with early intervention 111; and (c) the effects of AR on school performance and education56 support focusing of treatment on developmental/career milestones. Therefore, the consideration of AIT at early time points, using risk in addition to severity as a key selection criterion, is expected to maximize impact on the natural history of the disease as well as on cost/burden.

More studies are needed to characterize the long-term effects of AIT. Such studies cannot be randomized and, even less, blinded. Therefore, observational approaches, such as registry research, need to be used.112

In addition, there are opportunities for disease prevention that have not been adequately explored, such as primary prevention. We need more evidence on whether AIT may play a role for the prevention of allergic sensitization, the first allergic disease.9 Support for such studies needs to come from governmental organizations/public sources, in order to identify optimal cost-efficacy strategies.

11.5 Allergen immunotherapy in older age adults

The immunologic and allergic characteristics of older allergic patients differ from those of young and middle-aged adults. Limited studies have found that AIT may be effective in this population.113, 114 More data are certainly required for a strong recommendation. At this point, and before making the decision to initiate AIT in older patients, physicians need to have strong indications for the role of specific allergens in these patients’ AR or asthma and to take into account nonallergic co-morbidities that may have impact on the safety of AIT.

12 MHEALTH IN THE AIT PRECISION MEDICINE APPROACH

12.1 Patient stratification

It is recommended to stratify AR patients who are uncontrolled despite appropriate treatment and adherence to treatment.115 This can easily be achieved using electronic diaries obtained by cell phones as demonstrated in MASK-air®.2, 3, 47 Such diaries should include the full list of medications. After a single year of survey, physicians can assess whether SCUAD is present and could initiate AIT if (a) symptoms are associated with pollen season, (b) adherence to pharmacologic treatment is achieved, (c) the duration of uncontrolled symptoms was long enough and (d) an impact on work or school productivity was observed. Moreover, asthma and eye symptoms can be recorded, as in MASK-air® 2 and other Apps, allowing the evaluation of the role of multimorbidity.

12.2 Follow-up of patients under AIT

The same approach can be proposed for the follow-up of patients on AIT to assess its efficacy as suggested by a panel of international experts in an AIT position paper.18

12.3 Electronic clinical decision support system

The AR algorithm has been digitalized in tablets for healthcare professionals.46

13 CONCLUSIONS

AIT is an effective treatment for allergic diseases caused by inhaled allergens. Its use should, however, be restricted to carefully selected patients who are unresponsive to appropriate pharmacotherapy according to guidelines and for whom effective and cost-effective AIT is available. The present report reviews care pathways for the administration of AIT using evidence-based criteria. It is hoped that these recommendations will be considered by healthcare professionals, so that the appropriate usage of AIT will maximize its impact on allergic diseases.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr Claus Bachert reports personal fees from Uriach. Dr Bosnic-Anticevich reports personal fees from TEVA, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, AstraZeneca and GSK, and grants from TEVA and MEDA, outside the submitted work. Dr Bousquet reports personal fees and other from Chiesi, Cipla, Hikma, Menarini, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, Teva and Uriach, and other from Kyomed, outside the submitted work. Dr Cardona reports personal fees from Allergopharma, ALK, Diater, Leti and Thermo Fisher, outside the submitted work. Dr Casale reports grants and personal fees from Stallergenes, outside the submitted work. Dr Cecchi reports personal fees from Menarini, Malesci and ALK, outside the submitted work. Dr Cruz reports grants and personal fees from GSK, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and MEDA, personal fees from Novartis, Boston Scientific and Eurofarma, and nonfinancial support from CHIESI, outside the submitted work. Dr Durham reports personal fees from Adiga, Anergis, ALK, Allergopharma, MedicalUpdate GmBC and UCB, outside the submitted work. Dr Du Toit reports personal fees from Stallergenes, outside the submitted work. Dr Ebisawa reports personal fees from DBV Technologies, Mylan EPD, Maruho, Shionogi & CO., Ltd., Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Thermo Fisher Diagnostics, Pfizer, Beyer, Nippon Chemifar, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and MSD, outside the submitted work. Dr Gerth van Wijk reports personal fees from ALK Abello and Allergopharma, outside the submitted work. Dr Haahtela reports personal fees from Orion Pharma and Mundipharma, during the conduct of the study. Dr Hellings reports grants from Mylan, other from Stallergenes, Allergopharma and Sanofi, during the conduct of the study, and grants from Mylan. Dr Ivancevich reports personal fees from Eurofarma Argentina and Faes Farma, and other from Sanofi and Laboratorios Casasco, outside the submitted work. Dr Kvedariene reports personal fees from GSK and Berlin Chemie Menarini, and nonfinancial support from StallergenGreer, Mylan and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. Larenas Linnemann reports personal fees from GSK, AstraZeneca, MEDA, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Grunenthal, UCB, Amstrong, Siegfried, DBV Technologies, MSD and Pfizer and grants from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Novartis, UCB, GSK, TEVA, Chiesi and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Dr Okamoto reports personal fees from Shionogi Co. Ltd., Torii Co. Ltd., GSK, MSD, Kyowa Co. Ltd. and Eisai Co. Ltd., grants and personal fees from Kyorin Co. Ltd. and Tiho Co. Ltd. and grants from Yakuruto Co. Ltd. and Yamada Bee Farm, outside the submitted work. Dr Papadopoulos reports personal fees from Abbvie Novartis, Faes Farma, BIOMAY, HAL, Nutricia Research, Menarini, Novartis, MEDA, MSD, Omega Pharma and Danone, and grants from Menarini, outside the submitted work. Dr Panzner reports personal fees from ALK, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Stallergenes, outside the submitted work. Dr Pfaar reports grants and personal fees from ALK-Abelló, Allergopharma, Stallergenes Greer, HAL Allergy Holding BV/HAL Allergie GmbH, Bencard Allergie GmbH/Allergy Therapeutics, Lofarma, ASIT Biotech Tools SA, Laboratorios LETI/LETI Pharma and Anergis SA, grants from Biomay, Nuvo and Circassia, personal fees from Novartis Pharma, MEDA Pharma, Mobile Chamber Experts (a GA2LEN Partner), Pohl-Boskamp and Indoor Biotechnologies, and grants from GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. Dr Scadding reports personal fees from ALK and Seqirus, outside the submitted work. Dr Sheikh reports grants from EAACI, outside the submitted work. Dr Todo-Bom reports grants and personal fees from Teva and Mundipharma, personal fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Novartis, and grants from Bial and Leti, outside the submitted work. Dr Wallace reports other from ALK, outside the submitted work. Waserman reports personal fees from Merck, GSK, Novartis, Behring, Shire, Sanofi, Barid Aralez, Mylan Meda and Pediapharm outside the submitted work. Dr Zuberbier reports and Organizational affiliations: Committee member: WHO-Initiative "Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma" (ARIA). Member of the Board: German Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI). Head: European Centre for Allergy Research Foundation (ECARF); Secretary General: Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN). Member: Committee on Allergy Diagnosis and Molecular Allergology, World Allergy Organization (WAO).