The EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria

Abstract

This evidence- and consensus-based guideline was developed following the methods recommended by Cochrane and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group. The conference was held on 1 December 2016. It is a joint initiative of the Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), the EU-founded network of excellence, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA²LEN), the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and the World Allergy Organization (WAO) with the participation of 48 delegates of 42 national and international societies. This guideline was acknowledged and accepted by the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). Urticaria is a frequent, mast cell-driven disease, presenting with wheals, angioedema, or both. The lifetime prevalence for acute urticaria is approximately 20%. Chronic spontaneous urticaria and other chronic forms of urticaria are disabling, impair quality of life and affect performance at work and school. This guideline covers the definition and classification of urticaria, taking into account the recent progress in identifying its causes, eliciting factors and pathomechanisms. In addition, it outlines evidence-based diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for the different subtypes of urticaria.

Abstract

Abbreviations

-

- AAS

-

- angioedema activity score

-

- ACE

-

- angiotensin-converting enzyme

-

- AE-QoL

-

- angioedema quality of life questionnaire

-

- AGREE

-

- appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation

-

- AOSD

-

- adult-onset Still's disease

-

- ARIA

-

- allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma

-

- ASST

-

- autologous serum skin test

-

- BAT

-

- basophil activation test

-

- CAPS

-

- cryopyrin-associated periodic symptoms

-

- CIndU

-

- chronic inducible urticaria

-

- CNS

-

- central nervous system

-

- CSU

-

- chronic spontaneous urticaria

-

- CU

-

- chronic urticaria

-

- CU-Q2oL

-

- chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire

-

- CYP

-

- cytochrome P

-

- EAACI

-

- European academy of allergology and clinical immunology

-

- EDF

-

- European dermatology forum

-

- EtD

-

- evidence-to-decisions

-

- FCAS

-

- familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome

-

- GA2LEN

-

- global asthma and allergy European network

-

- GDT

-

- guideline development tool

-

- GRADE

-

- grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation

-

- HAE

-

- hereditary angioedema

-

- HIDS

-

- hyper-IgD syndrome

-

- IVIG (also IGIV)

-

- intravenous immunoglobulins

-

- MWS

-

- Muckle-Wells syndrome

-

- NOMID

-

- neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease

-

- NSAID

-

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

-

- PAF

-

- platelet-activating factor

-

- PET

-

- positron-emission tomography

-

- PICO

-

- technique used in evidence-based medicine, acronym stands for patient/problem/population, intervention, comparison/control/comparator, outcome

-

- REM

-

- rapid eye movement

-

- sgAH

-

- 2nd-generation antihistamine

-

- sJIA

-

- systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis

-

- TRAPS

-

- tumour necrosis factor receptor alpha-associated periodic syndrome

-

- UAS

-

- urticaria activity score

-

- UCT

-

- urticaria control test

-

- UEMS

-

- European union of medical specialists

-

- UV

-

- ultraviolet

-

- WAO

-

- World Allergy Organization

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

1 INTRODUCTION

This evidence- and consensus-based guideline was developed following the methods recommended by Cochrane and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group. A structured consensus process was used to discuss and agree upon recommendations. The conference was held on 1 December 2016 in Berlin, Germany.

It is a joint initiative of Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), the EU-founded network of excellence, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA²LEN), the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), and the World Allergy Organization (WAO), all of which provided funding for the development of this updated and revised version of the EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline on urticaria.1-4 There was no funding from other sources.

This revision and update of the guidelines were developed by 44 urticaria experts from 25 countries, all of which are delegates of national and/or international medical societies (Table 1). All of the societies involved endorse this guideline and have supported its development by covering the travel expenses for the participation of their delegate(s) in the consensus conference. The development of this revision and update of the guideline were supported by a team of methodologists led by Alexander Nast and included the contributions of the participants of the consensus conference (see Table 1).

| First name | Last name | Delegate of/affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Alexander | Nast | Division of Evidence-Based Medicine, Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin; Berlin, Germany |

| Corinna | Dressler | |

| Stefanie | Rosumeck | |

| Ricardo N | Werner | |

| Werner | Aberer | ÖGDV |

| Amir Hamzah | Abdul Latiff | MSAI |

| Riccardo | Asero | AAIITO |

| Diane | Baker | AAD |

| Barbara | Ballmer-Weber | SGAI |

| Jonathan A. | Bernstein | AAAAI |

| Carsten | Bindslev-Jensen | DSA, EAACI |

| Zenon | Brzoza | PSA |

| Roberta | Buense Bedrikow | SBD |

| Walter | Canonica | WAO, SIAAIC |

| Martin | Church | GA²LEN |

| Timothy | Craig | ACAAI |

| Inna Vladimirovna | Danilycheva | RAACI |

| Luis Felipe | Ensina | ASBAI |

| Ana | Giménez-Arnau | EAACI, AEDV |

| Kiran | Godse | IADVL |

| Margarida | Gonçalo | SPDV |

| Clive | Grattan | BSACI, EAACI |

| Jaques | Hebert | CSACI |

| Michihiro | Hide | JDA |

| Allen | Kaplan | WAO |

| Alexander | Kapp | DDG |

| Constance | Katelaris | ASCIA, APAAACI |

| Emek | Kocatürk | TSD |

| Kanokvalai | Kulthanan | DST (joined expert panel in October 2016) |

| Désirée | Larenas-Linnemann | CMICA |

| Tabi Anika | Leslie | BAD |

| Markus | Magerl | UNBB |

| Pascale | Mathelier-Fusade | SFD, GUS (Groupe Urticarie de la Société francaise de dermatologie) which is one of the subgroups of the SFD |

| Marcus | Maurer | EAACI |

| Raisa Yakovlevna | Meshkova | RAACI |

| Martin | Metz | EMBRN |

| Hanneke | Oude-Elberink | NvvA |

| Sarbjit | Saini | AAAAI, WAO |

| Mario | Sánchez-Borges | WAO |

| Peter | Schmid-Grendelmeier | SSDV |

| Petra | Staubach | UNEV |

| Gordon | Sussman | CSACI |

| Elias | Toubi | IAACI |

| Gino Antonio | Vena | SIDeMaST |

| Christian | Vestergaard | DDS |

| Bettina | Wedi | DGAKI |

| Zuotao | Zhao | CDA |

| Torsten | Zuberbier | EDF, GA²LEN |

The wide diversity and number of different urticaria subtypes that have been identified reflect, at least in part, our increasing understanding of the causes and eliciting factors of urticaria as well as the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in its pathogenesis. The aim of this guideline is to provide a definition and classification of urticaria, thereby facilitating the interpretation of divergent data from different centres and areas of the world regarding underlying causes, eliciting factors, burden to patients and society, and therapeutic responsiveness of subtypes of urticaria. Furthermore, this guideline provides recommendations for diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in common subtypes of urticaria. This guideline is a global guideline and takes into consideration that causative factors in patients, medical systems and access to diagnosis and treatment vary in different countries.

2 METHODS

The detailed methods used to develop this revision and update of the EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline on urticaria are published as separate methods report, including all GRADE tables.5

In summary, this updated and revised guideline takes into account the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) Instrument6 and the methods suggested by the GRADE working group. The literature review was conducted using the methods given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.7

Experts from 42 societies were nominated to be involved in the development of the guideline. First, key questions and relevant outcomes were selected and rated by the experts using an online survey tool.8 Twenty-three key questions were chosen by 30 members of the expert panel.

Subsequently, we developed a literature review protocol, which specified our literature search strategy, researchable questions (PICO), eligibility criteria, outcomes as chosen by the experts, the risk of bias assessment, and strategies for data transformation, synthesis and evaluation.

The systematic literature search was conducted on 1 June 2016 and yielded 8090 hits. Two independent reviewers evaluated the literature and extracted eligible data. After 2 screening phases, 65 studies were determined to fulfil the inclusion criteria. Wherever possible, we calculated effect measures with confidence intervals and performed meta-analyses using Review Manager.9 We assessed the quality of the evidence following GRADE using GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GDT).10, 11 Five criteria (namely, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias) were evaluated for each outcome resulting in an overall assessment of quality of evidence (Table 2). Effect measures such as risk ratios express the size of an effect, and the quality rating expresses how much trust one can have in a result.

| High (++++) | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. |

| Moderate (+++) | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

| Low (++) | Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

| Very low (+) | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. |

Subsequently modified evidence-to-decisions (EtD) frameworks were created to help the experts make a judgement on the size of the desirable and the undesirable effect, the balance of the 2, and to provide an overview of quality. The evidence assessment yielded 31 GRADE evidence profiles/evidence-to-decision frameworks. A recommendation for each evidence-based key question was drafted using standardized wording (Table 3).

| Type of recommendation | Wording | Symbols | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong recommendation for the intervention | “We recommend …” | ↑↑ | We believe that all or almost all informed people would make that choice. Clinicians will have to spend less time on the process of decision making and may devote that time to overcome barriers to implementation and adherence. In most clinical situations, the recommendation may be adopted as a policy |

| Conditional recommendation for the intervention | “We suggest …” | ↑ | We believe that most informed people would make that choice, but a substantial number would not. Clinicians and healthcare providers will need to devote more time on the process of shared decision making. Policymakers will have to involve many stakeholders and policymaking requires substantial debate |

| Conditional recommendation for either the intervention of the comparison | “We cannot make a recommendation with respect to …” | 0 | At the moment, a recommendation in favour or against an intervention cannot be made due to certain reasons (eg, no evidence data available, conflicting outcomes) |

| Conditional recommendation against the intervention | “We suggest against …” | ↓ | We believe that most informed people would make a choice against that intervention, but a substantial number would not |

| Strong recommendation against the intervention | “We recommend against …” | ↓↓ | We believe that all or almost all informed people would make a choice against that intervention. This recommendation can be adopted as a policy in most clinical situations |

In a preconference online voting round, all GRADE tables EtD frameworks and draft recommendations were presented and voted on. Of the 41 invited participants (expert panel), 30 completed the survey (response rate 73%). The results were either fed back to the expert panel or integrated into the EtD frameworks. All EtD frameworks and draft recommendations were made available to the participants before the consensus conference.

During the conference, all recommendations were voted on by over 250 participants, all of whom had to submit a declaration that they were (i) a specialist seeing urticaria patients and (ii) gave a declaration of conflict of interest. A nominal group technique was used to come to an agreement on the different recommendations.12 The consensus conference followed a structured approach: presentation of the evidence and draft recommendation, open discussion, initial voting or collection of alternative wording and final voting, if necessary. Participants eligible for voting had received one green and one red card, either of which they held up when voting for or against a suggested recommendation. Voting results were documented. Strong consensus was defined as >90% agreement, and 70-89% was documented as consensus. All recommendations passed with a 75% agreement. An internal and an external review took place.

All consented recommendations are highlighted in grey, and it is indicated whether these are based on expert opinion (based on consensus) or evidence and expert opinion (based on evidence and consensus).

3 DEFINITION

3.1 Definition

Urticaria is a condition characterized by the development of wheals (hives), angioedema or both. Urticaria needs to be differentiated from other medical conditions where wheals, angioedema or both can occur, for example anaphylaxis, auto-inflammatory syndromes, urticarial vasculitis or bradykinin-mediated angioedema including hereditary angioedema (HAE).

|

Definition Urticaria is a condition characterized by the development of wheals (hives), angioedema or both. |

- wheal in patients with urticaria has 3 typical features:

- a central swelling of variable size, almost invariably surrounded by reflex erythema,

- an itching or sometimes burning sensation,

- a fleeting nature, with the skin returning to its normal appearance, usually within 30 minutes to 24 hours.

- Angioedema in urticaria patients is characterized by:

- a sudden, pronounced erythematous or skin coloured swelling of the lower dermis and subcutis or mucous membranes,

- sometimes pain, rather than itch.

- a resolution slower than that of wheals (can take up to 72 hours).

3.2 Classification of urticaria on the basis of its duration and the relevance of eliciting factors

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of different urticaria subtypes is very wide. Additionally, 2 or more different subtypes of urticaria can coexist in any given patient.

Acute spontaneous urticaria is defined as the occurrence of spontaneous wheals, angioedema or both for less than 6 weeks.

| How should urticaria be classified? | ||

|

We recommend that urticaria is classified based on its duration as acute (≤ 6 weeks) or chronic (>6 weeks). We recommend that urticaria is classified as spontaneous (no specific eliciting factor involved) or inducible (specific eliciting factor involved). (consensus-based) |

↑↑ | >90% consensus |

Table 4 presents a classification of chronic urticaria (CU) subtypes for clinical use. This classification has been maintained from the previous guideline by consensus (>90%) urticarial vasculitis, maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (formerly called urticaria pigmentosa), auto-inflammatory syndromes (eg, cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes or Schnitzler's syndrome), nonmast cell mediator-mediated angioedema (eg, bradykinin-mediated angioedema) and other diseases such as syndromes that can manifest with wheals and/or angioedema are not considered to be subtypes of urticaria, due to their distinctly different pathophysiologic mechanisms (Table 5).

| Chronic urticaria subtypes | |

|---|---|

| Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria (CSU) | Inducible Urticaria |

| Spontaneous appearance of wheals, angioedema or both for > 6 weeks due to knowna or unknown causes |

Symptomatic dermographismb Cold urticariac Delayed pressure urticariad Solar urticaria Heat urticariae Vibratory angioedema Cholinergic urticaria Contact urticaria Aquagenic urticaria |

- a For example, autoreactivity, that is the presence of mast cell-activating auto-antibodies.

- b Also called urticaria factitia or dermographic urticaria.

- c Also called cold contact urticaria.

- d Also called pressure urticaria.

- e Also called heat contact urticaria.

|

- These diseases and syndromes are related to urticaria (1) because they can present with wheals, angioedema or both and/or (2) because of historical reasons.

| Should we maintain the current guideline classification of chronic urticaria? | ||

|

We recommend that the current guideline classification of chronic urticaria should be maintained. (consensus-based) |

↑↑ | >90% consensus |

3.3 Pathophysiological aspects

Urticaria is a mast cell-driven disease. Histamine and other mediators, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF) and cytokines released from activated skin mast cells, result in sensory nerve activation, vasodilatation and plasma extravasation as well as cell recruitment to urticarial lesions. The mast cell-activating signals in urticaria are ill-defined and likely to be heterogeneous and diverse. Histologically, wheals are characterized by oedema of the upper and mid dermis, with dilatation and augmented permeability of the postcapillary venules, as well as lymphatic vessels of the upper dermis leading to leakage of serum into the tissue. In angioedema, similar changes occur primarily in the lower dermis and the subcutis. Skin affected by wheals virtually always exhibits upregulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules, neuropeptides and growth factors and a mixed inflammatory perivascular infiltrate of variable intensity, consisting of neutrophils with or without eosinophils, basophils, macrophages and T cells but without vessel-wall necrosis, which is a hallmark of urticarial vasculitis.13-17 The nonlesional skin of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients shows upregulation of adhesion molecules,18 infiltrating eosinophils and altered cytokine expression.19 A mild to moderate increase in mast cell numbers has also been reported by some authors. These findings underline the complex nature of the pathogenesis of urticaria, which has many features in addition to the release of histamine from dermal mast cells.20-22 Some of these features of urticaria are also seen in a wide variety of inflammatory conditions and are thus not specific or of diagnostic value. A search for more specific histological biomarkers for different subtypes of urticaria and for distinguishing urticaria from other conditions is desirable.23

3.4 Burden of disease

The burden of CU for patients, their family and friends, the healthcare system and society is substantial. The use of patient-reported outcome measures such as the urticaria activity score (UAS), the angioedema activity score (AAS), the CU quality of life questionnaire (CU-Q2oL), the angioedema quality of life questionnaire (AE-QoL) and the urticaria control test (UCT) in studies and clinical practice has helped to better define the effects and impact of CU on patients.24 The available data indicate that urticaria markedly affects both objective functioning and subjective well-being.25-27 Previously, O'Donnell et al showed that health status scores in CSU patients are comparable to those reported by patients with coronary artery disease.28 Furthermore, both health status and subjective satisfaction in patients with CSU are lower than in healthy subjects and in patients with respiratory allergy.29 CU also has considerable costs to patients and the society.30-32

4 DIAGNOSIS OF URTICARIA

4.1 Diagnostic work up in Acute Urticaria

Acute urticaria usually does not require a diagnostic workup, as it is usually self-limiting. The only exception is the suspicion of acute urticaria due to a type I food allergy in sensitized patients or the existence of other eliciting factors such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In this case, allergy tests as well as educating the patients may be useful to allow patients to avoid re-exposure to relevant causative factors.

| Should routine diagnostic measures be performed in acute urticaria? | ||

| We recommend against any routine diagnostic measures in acute spontaneous urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↓↓ | >90% consensus |

4.2 The diagnostic work up in CU

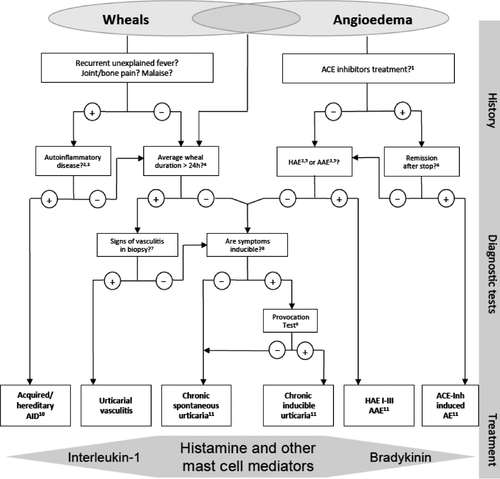

The diagnostic work up of CSU has 3 major aims: (i) to exclude differential diagnoses, (ii) to assess disease activity, impact and control and (iii) to identify triggers of exacerbation or, where indicated, any underlying causes. Ad (1) Wheals or angioedema can be present in some other conditions, too. In patients who display only wheals (but no angioedema), urticarial vasculitis and auto-inflammatory disorders such as Schnitzler syndrome or cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) need to be ruled out. On the other hand, in patients who suffer only from recurrent angioedema (but not from wheals), bradykinin-mediated angioedema-like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-induced angioedema or other nonmast cell-related angioedema, that is HAE type 1-3, should be considered as differential diagnoses (Figure 1). Ad (2) Baseline assessment of disease activity (UAS, AAS), quality of life (CU-Q2oL, AE-QoL) and disease control (UCT) are indispensable for guiding treatment decisions, providing better insights into the patients’ disease burden, as well as facilitating, improving and standardizing the increasingly important documentation work (see also section on Assessment of disease activity, impact, and control). Ad (3) History taking is essential in patients with urticaria, as exacerbating triggers are variable. Further diagnostic procedures to reveal underlying causes in patients with long-standing and uncontrolled disease need to be determined carefully.

In the last decades, many advances have been made in identifying causes of different types and subtypes of urticaria, for example in CSU.33-35 Among others, autoimmunity mediated by functional auto-antibodies directed against the high-affinity IgE receptor or IgE-auto-antibodies to auto-antigens, pseudo-allergy (nonallergic hypersensitivity reactions) to foods or drugs, and acute or chronic infections (eg, Helicobacter pylori or Anisakis simplex) have been described as causes of CU (Table 6). However, there are considerable variations in the frequency of underlying causes in the different studies. This also reflects regional differences in the world, for example differences in diets and the prevalence of infections. Thus, it is important to remember that not all possible causative factors need to be investigated in all patients, and the first step in diagnosis is a thorough history, taking the following items into consideration:

| Types | Subtypes | Routine diagnostic tests (recommended) | Extended diagnostic programmea (based on history) For identification of underlying causes or eliciting factors and for ruling out possible differential diagnoses if indicated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous urticaria | Acute spontaneous urticaria | None | Noneb |

| CSU | Differential blood count. ESR and/or CRP | Avoidance of suspected triggers (eg, drugs); Conduction of diagnostic tests for (in no preferred order): (i) infectious diseases (eg, Helicobacter pylori); (ii) functional auto-antibodies (eg, autologous skin serum test); (iii) thyroid gland disorders (thyroid hormones and auto-antibodies); (iv) allergy (skin tests and/or allergen avoidance test, eg, avoidance diet); (v) concomitant CIndU, see below69; (vi) severe systemic diseases (eg, tryptase); (vii) other (eg, lesional skin biopsy) | |

| Inducible urticaria | Cold urticaria | Cold provocation and threshold testc,d | Differential blood count and ESR or CRP, rule out other diseases, especially infections168 |

| Delayed pressure urticaria | Pressure test and threshold testc,d | None | |

| Heat urticaria | Heat provocation and threshold testc,d | None | |

| Solar urticaria | UV and visible light of different wavelengths and threshold testc | Rule out other light-induced dermatoses | |

| Symptomatic dermographism | Elicit dermographism and threshold testc,d | Differential blood count, ESR or CRP | |

| Vibratory angioedema | Test with vibration, for example Vortex or mixerd | None | |

| Aquagenic urticaria | Provocation testingd | None | |

| Cholinergic urticaria | Provocation and threshold testingd | None | |

| Contact urticaria | Provocation testingd | None |

- ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

- a Depending on suspected cause.

- b Unless strongly suggested by patient history, for example allergy.

- c All tests are carried out with different levels of the potential trigger to determine the threshold.

- d For details on provocation and threshold testing see.69

- Time of onset of disease

- Shape, size, frequency/duration and distribution of wheals

- Associated angioedema

- Associated symptoms, for example bone/joint pain, fever, abdominal cramps

- Family and personal history regarding wheals and angioedema

- Induction by physical agents or exercise

- Occurrence in relation to daytime, weekends, menstrual cycle, holidays and foreign travel

- Occurrence in relation to foods or drugs (eg, NSAIDs, ACE-inhibitors)

- Occurrence in relation to infections, stress

- Previous or current allergies, infections, internal/autoimmune diseases, gastric/intestinal problems or other disorders

- Social and occupational history, leisure activities

- Previous therapy and response to therapy including dosage and duration

- Previous diagnostic procedures/results

The second step of the diagnosis is the physical examination of the patient. Where it is indicated by history and/or physical examination, further appropriate diagnostic tests should be performed. The selection of these diagnostic measures largely depends on the nature of the urticaria subtype, as summarized in Figure 1 and Table 6.

| Should differential diagnoses be considered in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria? | ||

| We recommend that differential diagnoses be considered in all patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of chronic urticaria based on the guideline algorithm. (consensus-based) | ↑↑ | >90% consensus |

| What routine diagnostic measures should be performed in chronic spontaneous urticaria? | ||

|

We recommend limited investigations. Basic tests include differential blood count and CRP and/or ESR. (consensus-based) In CSU, we recommend performing further diagnostic measures based on the patient history and examination, especially in patients with long-standing and/or uncontrolled disease. (consensus-based) |

↑↑ | >90% consensus |

| Should routine diagnostic measures be performed in chronic inducible urticaria? | ||

|

We recommend using provocation testing to diagnose chronic inducible urticaria. We recommend to use provocation threshold measurements and the UCT to measure disease activity and control in patients with chronic inducible urticaria, respectively. (consensus-based) |

↑↑ | >90% consensus |

Intensive and costly general screening programs for causes of urticaria are strongly advised against. The factors named in Table 6 in the extended programme should only be investigated based on patient history. Type I allergy is an extremely rare cause of CSU. In contrast, pseudo-allergic (nonallergic hypersensitivity reactions) to NSAIDs or food may be more relevant for CSU. Diagnosis should be based on history of NSAID intake or a pseudo-allergic elimination diet protocol. Bacterial, viral, parasitic or fungal infections, for example with H. pylori, streptococci, staphylococci, Yersinia, Giardia lamblia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, hepatitis viruses, norovirus, parvovirus B19, Anisakis simplex, Entamoeba spp, Blastocystis spp, have been implicated to be underlying causes of urticaria.36-38 The frequency and relevance of infectious diseases vary considerably between different patient groups and different geographical regions. For example, Anisakis simplex, a sea fish nematode, has only been discussed as a possible cause of recurrent acute spontaneous urticaria in areas of the world where uncooked fish is eaten frequently.39, 40 The relevance of H. pylori, dental or ear, nose and throat infections also appears to vary between patient groups.38, 41-44 More research is needed to make definitive recommendations regarding the role of infection in urticaria.

Routine screening for malignancies in the diagnosis of underlying causes for urticaria is not suggested. Although it is noted that a slightly increased prevalence has been reported in Taiwan,45 there is not sufficient evidence available for a causal correlation of urticaria with neoplastic diseases. Ruling out malignancies is, however, warranted if patient history (eg, sudden loss of weight) points to this.

Currently, the only generally available tests to screen for auto-antibodies against either IgE or FcεR1 (the high-affinity IgE receptor) are the autologous serum skin test (ASST) and basophil activation tests (BATs). The ASST is a nonspecific screening test that evaluates the presence of serum histamine-releasing factors of any type, not just histamine-releasing auto-antibodies. The ASST should be performed with utmost care as infections might be transmitted if, by mistake, patients were injected with someone else's serum. The subject is further elucidated in a separate EAACI/GA2LEN position paper.46, 47

BATs assess histamine release or upregulation of activation markers of donor basophils in response to stimulation with the serum of CSU patients. BATs can help to co-assess disease activity in patients with urticaria 48, 49 as well as to diagnose autoimmune urticaria.50 Furthermore, BAT can be used as a marker for responsiveness to ciclosporin A or omalizumab.51, 52

In some subjects with active CSU, several groups have noted blood basopenia and that blood basophils exhibit suppressed IgE receptor-mediated histamine release to anti-IgE. Blood basophils are detected in skin lesions of CSU patients.19 CSU remission is associated with increases in blood basophil numbers and IgE receptor-triggered histamine response.53, 54 A rise in basophil number is also observed during anti-IgE treatment 55 This finding, however, needs to be examined in future research and currently does not lead to diagnostic recommendations. However, it should be noted that a low basophil blood count should not result in further diagnostic procedures. It is also known that levels of D-dimer are significantly higher in patients with active CSU and decrease according to the clinical response of the disease to omalizumab. The relevance of this finding is not yet clear, and currently, it is not recommended to measure D-dimer levels.56, 57

4.2.1 Assessment of disease activity impact and control

Disease activity in spontaneous urticaria should be assessed both in clinical care and trials with the UAS7 (Table 7), a unified and simple scoring system that was proposed in the last version of the guidelines and has been validated.58, 59 The UAS7 is based on the assessment of key urticaria signs and symptoms (wheals and pruritus), which are documented by the patient, making this score especially valuable. The use of the UAS7 facilitates comparison of study results from different centres. As urticaria activity frequently changes, the overall disease activity is best measured by advising patients to document 24-h self-evaluation scores once daily for several days. The UAS7, that is the sum score of 7 consecutive days, should be used in routine clinical practice to determine disease activity and response to treatment of patients with CSU. For patients with angioedema, a novel activity score, the angioedema activity score (AAS) has been developed and validated.60 In addition to disease activity, it is important to assess the impact of disease on quality of life as well as disease control both in clinical practice and trials. Recently, the urticaria control test (UCT) has become valuable in the assessment of patients’ disease status.61, 62 The UCT was developed and validated to determine the level of disease control in all forms of CU (CSU and CIndU). The UCT has only 4 items with a clearly defined cut-off for patients with “well-controlled” vs “poorly controlled” disease, and it is thus suited for the management of patients in routine clinical practice. The cut-off value for a well-controlled disease is 12 of 16 possible points. This helps to guide treatment decisions.

| Score | Wheals | Pruritus |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None |

| 1 | Mild (<20 wheals/24 h) | Mild (present but not annoying or troublesome) |

| 2 | Moderate (20-50 wheals/24 h) | Moderate (troublesome but does not interfere with normal daily activity or sleep) |

| 3 | Intense (>50 wheals/24 h or large confluent areas of wheals) | Intense (severe pruritus, which is sufficiently troublesome to interfere with normal daily activity or sleep) |

Patients should be assessed for disease activity, impact and control at the first and every follow up visit, acknowledging that some tools, for example the UAS can only be used prospectively and others, for example the UCT, allow for retrospective assessment. Validated instruments such as the UAS7, AAS, CU-Q2oL, AE-QoL and UCT should be used in CU for this purpose.

| Should patients with chronic urticaria be assessed for disease activity, impact, and control? | ||

| We recommend that patients with CU be assessed for disease activity, impact, and control at every visit. (consensus-based) | ↑↑ | >90% consensus |

| Which instruments should be used to assess and monitor disease activity in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients? | ||

| We suggest the use of the urticaria activity score, UAS7, and of the angioedema activity score, AAS, for assessing disease activity in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| Which instruments should be used to assess and monitor quality of life impairment in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients? | ||

| We suggest the use of the chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire, CU-Q2oL, and the angioedema quality of life questionnaire, AE-QoL, for assessing quality of life impairment in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| Which instruments should be used to assess and monitor disease control in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients? | ||

| We suggest the use of the urticaria control test, UCT, for assessing disease control in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

In CIndU, the threshold of the eliciting factor(s) should be determined to assess disease activity, for example critical temperature and stimulation time thresholds for cold provocation in cold urticaria. These thresholds allow both patients and treating physicians to evaluate disease activity and response to treatment.63-68

Sum of score: 0-6 for each day is summarized over one week (maximum 42).

4.3 The diagnostic work up in CIndU

In CIndUs, the routine diagnostic work up should follow the consensus recommendations on the definition, diagnostic testing and management of CIndUs.69 Diagnostics in CIndU are used to identify the subtype of CIndU and to determine trigger thresholds.69 The latter is important as it allows for assessing disease activity and response to treatment. For most types of CIndU, validated tools for provocation testing are meanwhile available.69 Examples include cold and heat urticaria, where a Peltier element-based provocation device (TempTest®) is available,70 symptomatic dermographism for which a dermographometer (FricTest®) has been developed,71, 72 and delayed pressure urticaria. In cholinergic urticaria, a graded provocation test with office-based methods, for example pulse-controlled ergometry, is available.66, 73 Patients with contact urticaria or aquagenic urticaria should be assessed by appropriate cutaneous provocation tests.69

4.4 Diagnosis in children

Urticaria can occur in all age groups, including infants and young children. Although data for childhood CSU are still sparse, recent investigations indicate that the prevalence of CIndUs and CSU, and underlying causes of CSU are very similar to the prevalence and causes in adults, with some minor differences.74-77

Thus, the diagnostic approaches for children should be similar to those in adults.

The diagnostic work up of CSU in children has the same aims as in adults: (i) differential diagnoses should be excluded with a special focus on cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). CAPS is a rare disease with a urticaria-like rash that manifests in childhood.78 (ii) If possible, that is depending on the age of the child, disease activity, impact and control should be assessed using assessment tools similar to those used in adults, although it has to be noted that no validated disease-specific tools for children are available as of now. (iii) Triggers of exacerbation should be identified and, where indicated, underlying causes, which appear to be similar to those in adults, should be searched for. In children with CIndU, similar tests for provocation and the determination of trigger thresholds should be performed.

5 MANAGEMENT OF URTICARIA

5.1 Basic considerations

- The goal of treatment is to treat the disease until it is gone.

- The therapeutic approach to CU can involve

- the identification and elimination of underlying causes,

- the avoidance of eliciting factors,

- tolerance induction, and/or

- the use of pharmacological treatment to prevent mast cell mediator release and/or the effects of mast cell mediators

- Treatment should follow the basic principles of treating as much as needed and as little as possible. This may mean stepping up or stepping down in the treatment algorithm according to the course of disease.

| Should treatment aim at complete symptom control in urticaria? | ||

| We recommend aiming at complete symptom control in urticaria, considering as much as possible the safety and the quality of life of each individual patient. (consensus-based) | ↑↑ | >90% consensus |

5.2 Identification and elimination of underlying causes and avoidance of eliciting factors

To eliminate an underlying cause, an exact diagnosis is a basic prerequisite. The identification of a cause in CU is, however, difficult in most cases, for example infections may be a cause, aggravating factor or unrelated. The only definite proof of a causative nature of a suspected agent or trigger is the remission of symptoms following elimination and recurrence of symptoms following re-challenge in a double-blind provocation test. Spontaneous remission of urticaria can occur any time, the elimination of a suspected cause or trigger can also occur coincidentally.

5.2.1 Drugs

When these agents are suspected in the course of diagnostic work up, they should be omitted entirely or substituted by another class of agents if indispensable. Drugs causing nonallergic hypersensitivity reactions (the prototypes being NSAIDs) cannot only elicit, but can also aggravate pre-existing CSU,79 so that elimination in the latter case will only improve symptoms in some patients.

| Should patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria be advised to discontinue medication that is suspected to worsen the disease? | ||

| We recommend advising patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria to discontinue medication that is suspected to worsen the disease, for example NSAIDs. (consensus-based) | ↑↑ | >90% consensus |

5.2.2 Physical stimuli

Avoidance of physical stimuli for the treatment of CIndUs is desirable, but mostly very difficult to achieve. Detailed information about the physical properties of the respective stimulus should make the patient sufficiently knowledgeable to recognize and control exposure in normal daily life. Thus, for instance, it is important in delayed pressure urticaria and in symptomatic dermographism to point out that pressure is defined as force per area and that simple measures, such as broadening of the handle of heavy bags for pressure urticaria or reducing friction in case of symptomatic dermographism, may be helpful in the prevention of symptoms. Similar considerations hold for cold urticaria where the impact of the wind chill factor in cold winds needs to be remembered. For solar urticaria, the exact identification of the range of eliciting wavelengths may be important for the appropriate selection of sunscreens or for the selection of light bulbs with an UV-A filter. However, in many patients, the threshold for the relevant physical trigger is low and total avoidance of symptoms is virtually impossible. For example, severe symptomatic dermographism is sometimes confused with CSU because seemingly spontaneous hives are observed where even loose-fitting clothing rubs on the patient's skin or unintentional scratching by patients readily causes the development of wheals in that area.

5.2.3 Eradication of infectious agents and treatment of inflammatory processes

In contrast to CIndU, CSU is often reported to be associated with a variety of inflammatory or infectious diseases. This is regarded as significant in some instances, but some studies show conflicting results and have methodological weaknesses. These infections, which should be treated appropriately, include those of the gastrointestinal tract like H. pylori infection or bacterial infections of the nasopharynx80 (even if association with urticaria is not clear in the individual patient and a meta-analysis shows overall low evidence for eradication therapy,80 H. pylori should be eliminated as an association with gastric cancer is suggested81). Bowel parasites, a rare possible cause of CSU in developed industrial countries, should be eliminated if indicated.80, 82 In the past, intestinal candidiasis was regarded as a highly important underlying cause of CSU,80 but more recent findings fail to support a significant causative role.83 Apart from infectious diseases, chronic inflammatory processes due to diverse other diseases have been identified as potentially triggering CSU. This holds particularly for gastritis, reflux oesophagitis or inflammation of the bile duct or gall bladder.84, 85 However, similar to infections, it is not easily possible to discern whether any of these are relevant causes of CSU but should be treated as many of them may be also associated with development of malignancies.

5.2.4 Reduction of physical and emotional stress

Although the mechanisms of stress-induced exacerbation are not well investigated, some evidence indicates that disease activity and severity are correlated with stress levels.86 This holds true for emotional stress as well as physical stress which in some entities can be relevant for the development of symptoms such as in cholinergic urticaria.87

5.2.5 Reduction in functional auto-antibodies

Direct reduction in functional auto-antibodies by plasmapheresis has been shown to be of temporary benefit in some, severely affected patients.88 Due to limited experience and high costs, this therapy is suggested for auto-antibody-positive CSU patients who are unresponsive to all other forms of treatment.

5.2.6 Dietary management

IgE-mediated food allergy is extremely rarely the underlying cause of CSU.84, 89 If identified, the specific food allergens need to be omitted as far as possible which leads to a remission within less than 24 hours. In some CSU patients, pseudo-allergic reactions (non-IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions) to naturally occurring food ingredients and in some cases to food additives have been observed.84, 89-93 A pseudoallergen-free diet, containing only low levels of natural as well as artificial food pseudoallergens, has been tested in different countries 94 and also a low histamine diet may improve symptoms in those patients.95 Those diets are controversial and as yet unproven in well-designed double-blind placebo-controlled studies. However, when used, they must usually be maintained for a minimum of 2-3 weeks before beneficial effects are observed. However, it should be pointed out that this kind of treatment requires cooperative patients and success rates may vary considerably due to regional differences in food and dietary habits. More research is necessary on the effect of natural and artificial ingredients of food in causing urticaria.

5.3 Inducing tolerance

Inducing tolerance can be useful in some subtypes of urticaria. Examples are cold urticaria, cholinergic urticaria and solar urticaria, where even a rush therapy with UV-A has been proven to be effective within 3 days.96 However, tolerance induction is only lasting for a few days, and thus, a consistent daily exposure to the stimulus just at threshold level is required. Tolerance induction and maintenance are often not accepted by patients, for example in the case of cold urticaria where daily cold baths/showers are needed to achieve this.

5.4 Symptomatic pharmacological treatment

A basic principle of the pharmacological treatment is to aim at complete symptom relief. Another general principle in pharmacotherapy is to use as much as needed and as little as possible. The extent and selection of medication may therefore vary in the course of the disease.

The main option in therapies aimed at symptomatic relief is to reduce the effect of mast cell mediators such as histamine, PAF and others on the target organs. Many symptoms of urticaria are mediated primarily by the actions of histamine on H1-receptors located on endothelial cells (the wheal) and on sensory nerves (neurogenic flare and pruritus). Thus, continuous treatment with H1-antihistamines is of eminent importance in the treatment of urticaria (safety data are available for use of several years continuously). Continuous use of H1-antihistamines in CU is supported not only by the results of clinical trials97, 98 but also by the mechanism of action of these medications, that is that they are inverse agonists with preferential affinity for the inactive state of the histamine H1-receptor and stabilize it in this conformation, shifting the equilibrium towards the inactive state.

However, other mast cell mediators (PAF, leukotrienes, cytokines) can also be involved and a pronounced cellular infiltrate including basophils, lymphocytes and eosinophils may be observed.99 These may respond completely to a brief burst of corticosteroid and may be relatively refractory to antihistamines.

These general considerations on pharmacotherapy refer to all forms of acute and chronic urticaria. The difference between spontaneous urticaria and CIndU is, however, that in some forms of physical urticaria, for example cold urticaria instead of continuous treatment, on-demand treatment may be useful. In particular, if the patient knows of a planned trigger such as expected cold exposure, when going for a swim in summer, the intake of an antihistamine 2 hours prior to the activity may be sufficient.

Antihistamines have been available for the treatment of urticaria since the 1950s. The older first-generation antihistamines have pronounced anticholinergic effects and sedative actions on the central nervous system (CNS) and many interactions with alcohol and drugs affecting the CNS, such as analgesics, hypnotics, sedatives and mood elevating drugs, have been described. They can also interfere with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and impact on learning and performance. Impairment is particularly prominent during multi-tasking and performance of complex sensorimotor tasks such as driving. In a GA²LEN position paper,100 it is strongly recommended not to use first-generation antihistamines any longer in allergy both for adults and especially in children. This view is shared by the WHO guideline ARIA.101 Based on strong evidence regarding potential serious side effects of old sedating antihistamines (lethal overdoses have been reported), we recommend against the use of these sedating antihistamines for the routine management of CU as first-line agents, except for the rare places worldwide in which modern 2nd-generation antihistamines are not available. The side effects of first-generation H1-antihistamines are most pronounced for promethazine, diphenhydramine, ketotifen and chlorphenamine and are well understood. They penetrate the blood-brain barrier, bind to H1-receptors in the CNS and interfere with the neurotransmitter effects of histamine. Positron-emission tomography (PET) studies document their penetration into the human brain and provide a new standard whereby CNS H1-receptor occupancy can be related directly to effects on CNS function.102

The development of modern 2nd-generation antihistamines led to drugs which are minimally or nonsedating and free of anticholinergic effects. However, 2 of the earlier modern 2nd-generation drugs, astemizole and terfenadine, which were essentially pro-drugs requiring hepatic metabolism to become fully active, had cardiotoxic effects if this metabolism was blocked by concomitant administration of inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 isoenzyme, such as ketoconazole or erythromycin. These 2 drugs are no longer available in most countries, and we recommend that they are not used.

Further progress with regard to drug safety has been achieved in the last few decades with a considerable number of newer modern 2nd-generation antihistamines.102 Not all antihistamines have been tested specifically in urticaria, but many nonsedating antihistamines studies are available, for example cetirizine, desloratadine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine, loratadine, ebastine, rupatadine and bilastine. Modern 2nd-generation antihistamines should be considered as the first-line symptomatic treatment for urticaria because of their good safety profile. However, up to date, well-designed clinical trials comparing the efficacy and safety of modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines in urticaria are largely lacking.

| Are 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines to be preferred over 1st-generation H1-antihistamines for the treatment of chronic urticaria? | ||

| We suggest 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines over 1st-generation H1-antihistamines for the treatment of patients with chronic urticaria. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| Should modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines be used as first-line treatment of urticaria? | ||

| We recommend 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines as first-line treatment of chronic urticaria. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | ↑↑ | >90% consensus |

| Should modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines be taken regularly or as needed by patients with chronic urticaria? | ||

| We suggest 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines to be taken regularly for the treatment of patients with chronic urticaria. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| Should different 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines be used at the same time? | ||

| We recommend against using different H1-antihistamines at the same time. (consensus-based) | ↓↓ | >90% consensus |

There are studies showing the benefit of a higher dosage of 2nd-generation antihistamines in individual patients103-105 corroborating earlier studies which came to the same conclusion employing first-generation antihistamines.106, 107 This has been verified in studies using up- to fourfold higher than recommended doses of bilastine, cetirizine, desloratadine, ebastine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine and rupatadine.103, 104, 108-111

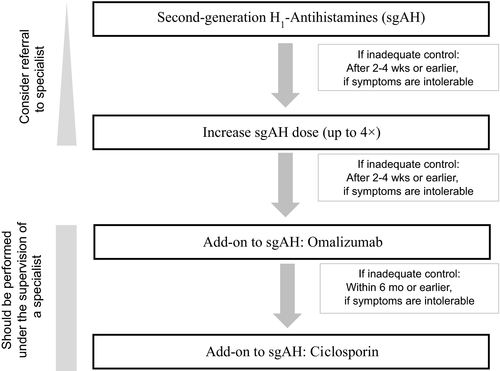

In summary, these studies suggest that the majority of patients with urticaria not responding to standard doses will benefit from up-dosing of antihistamines. Modern 2nd-generation antihistamines at licensed doses are first-line treatment in urticaria and up-dosing is second-line treatment (Figure 2).

Recommended treatment algorithm for urticaria*

Chronic urticaria treatment algorithm. This algorithm was voted on after finishing all separate GRADE questions taking into consideration the existing consensus. It was decided that omalizumab should be tried before ciclosporin A since the latter is not licensed for urticaria and has an inferior profile of adverse effects. In addition: A short course of glucocorticosteroids may be considered in case of severe exacerbation. Other treatment options are available, see Table 9. >90% consensus.

- First line = High-quality evidence: Low cost and worldwide availability (eg, modern 2nd-generation antihistamines exist also in developing countries mostly cheaper than old sedating antihistamines), per daily dose as the half life time is much longer, very good safety profile, good efficacy

- Second line = high-quality evidence: Low cost, good safety profile, good efficacy

- Third line as add-on to antihistamine

- Omalizumab = High-quality evidence: High cost, very good safety profile, very good efficacy

- Fourth line as add-on

- Ciclosporin A = High-quality evidence: Medium to high cost, moderate safety profile, good efficacy

- Short course of corticosteroids = Low-quality evidence: Low cost, worldwide availability, good safety profile (for short course only), good efficacy during intake, but not suitable for long-term therapy

| Is an increase in the dose to fourfold of modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines useful and to be preferred over other treatments in urticaria (second-line treatment)? | ||

| We suggest up-dosing 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines up to fourfold in patients with chronic urticaria unresponsive to 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines onefold. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| If there is no improvement, should higher than fourfold doses of 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines be used? | ||

| We recommend against using higher than fourfold standard dosed H1-antihistamines in chronic urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↓↓ | > 90% consensus |

5.5 Further therapeutic possibilities for antihistamines-refractory patients

Omalizumab (anti-IgE) has been shown to be very effective and safe in the treatment of CSU.112-117 Omalizumab has also been reported to be effective in CIndU118, 119 including cholinergic urticaria,120 cold urticaria,68, 121 solar urticaria,122 heat urticaria,123 symptomatic dermographism,67, 124 as well as delayed pressure urticaria.125 In CSU, omalizumab prevents angioedema development,126 markedly improves quality of life,9, 127 is suitable for long-term treatment128 and effectively treats relapse after discontinuation.128, 129 Omalizumab, in CU, is effective at doses from 150 to 300 mg per month. Dosing is independent of total serum IgE.112 The recommended dose in CSU is 300 mg every 4 weeks. The licensed doses and treatment duration vary between different countries.

| Is omalizumab useful as add-on treatment in patients unresponsive to high doses of H1-antihistamines (third-line treatment of urticaria)? | ||

|

We recommend adding on omalizumab* for the treatment of patients with CU unresponsive to 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines. (evidence-based and consensus-based) *currently licensed for urticaria |

↑↑ | >90% consensus |

Ciclosporin A also has a moderate, direct effect on mast cell mediator release.130, 131 Efficacy of ciclosporin A in combination with a modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamine has been shown in placebo-controlled trials 132-134 as well as open controlled trials 135 in CSU, but this drug cannot be recommended as standard treatment due to a higher incidence of adverse effects.133 Ciclosporin A is off-label for urticaria and is recommended only for patients with severe disease refractory to any dose of antihistamine and omalizumab in combination. However, ciclosporin A has a far better risk/benefit ratio compared with long-term use of steroids.

| Is ciclosporin A useful as add-on treatment in patients unresponsive to high doses of H1-antihistamines (third-line treatment of urticaria)? | ||

| We suggest adding on ciclosporin A for the treatment of patients with CU unresponsive to 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

| Comment by the authors: as shown in the consensus-based treatment algorithm (Figure 2), which was voted on later, it was decided that omalizumab should be tried before ciclosporin A as the latter is not licensed for urticaria and has an inferior profile of adverse effects. | ||

Some previous RCTs have assessed the use of leukotriene receptor antagonists. Studies are difficult to compare due to different populations studied, for example inclusion of only aspirin and food additive intolerant patients or exclusion of ASST-positive patients. In general, the level of evidence for the efficacy of leukotriene receptor antagonists in urticaria is low but best for montelukast.

| Are leukotriene antagonists useful as add-on treatment in patients unresponsive to high doses of H1-antihistamines? | ||

| We cannot make a recommendation with respect to montelukast as add-on treatment to H1-antihistamines in patients with chronic urticaria unresponsive to H1-antihistamines. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | 0 | >90% consensus |

At present, topical corticosteroids are frequently and successfully used in many allergic diseases, but in urticaria topical steroids are not helpful (with the possible exception of pressure urticaria on soles as alternative therapy with low evidence). If systemic corticosteroids are used, doses between 20 and 50 mg/day for prednisone are required with obligatory side effects on long-term use. There is a strong recommendation against the long-term use of corticosteroids outside specialist clinics. Depending on the country, it must be noted that steroids are also not licensed for CU (eg, in Germany prednisolone is only licensed for acute urticaria). For acute urticaria and acute exacerbations of CSU, a short course of oral corticosteroids, that is treatment of a maximum of up to 10 days, may, however, be helpful to reduce disease duration/activity.136, 137 Nevertheless, well-designed RCTs are lacking.

| Should oral corticosteroids be used as add-on treatment in the treatment of urticaria? | ||

| We recommend against the long-term use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in CU. (consensus-based) | ↓↓ | >90% consensus |

| We suggest considering a short course of systemic glucocorticosteroids in patients with an acute exacerbation of CU. (consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

While antihistamines at up to quadruple the manufacturers’ recommended dosages will control symptoms in a large part of patients with urticaria in general practice, alternative treatments are needed for the remaining unresponsive patients. Before changing to an alternative therapy, it is recommended to wait for 1-4 weeks to allow full effectiveness.

As the severity of urticaria may fluctuate, and spontaneous remission may occur at any time, it is also recommended to re-evaluate the necessity for continued or alternative drug treatment every 3-6 months.

Except for omalizumab and ciclosporin A, which both have restrictions due to their high cost, many of the alternative methods of treatment, such as combinations of modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines with leukotriene receptor antagonists, are based on clinical trials with low levels of evidence (Table 9). Based on the level of evidence, the recommended third-line and fourth-line treatment options are thus limited (see algorithm figure 2).

H₂-antagonists and dapsone, recommended in the previous versions of the guideline, are now perceived to have little evidence to maintain them as recommendable in the algorithm but they may still have relevance as they are very affordable in some more restricted healthcare systems. Sulphasalazine, methotrexate, interferon, plasmapheresis, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG/IGIV) and other treatment options have low-quality evidence, or just case series have been published2 (Table 9). Despite the lack of published evidence, all these drugs may be of value to individual patients in the appropriate clinical context.138

| Are H2-antihistamines useful as add-on treatment in patients unresponsive to low or high doses of H1-antihistamines? | ||

| We cannot make a recommendation for or against the combined use of H1-and H2-antagonists in patients with chronic urticaria. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | 0 | >75% consensus |

Antagonists of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha)139 and IVIG/IGIV,140-143 which have been successfully used in case reports, are recommended currently only to be used in specialized centres as last option (ie, anti-TNF-alpha for delayed pressure urticaria and IVIG/IGIV for CSU).144, 145

For the treatment of CSU and symptomatic dermographism, UV-B (narrow-band UV-B, TL01), UV-A and PUVA treatment for 1-3 months can be added to antihistamine treatment.146-148

Some treatment alternatives formerly proposed have been shown to be ineffective in double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and should no longer be used as the grade of recommendation is low. These include tranexamic acid and sodium cromoglycate in CSU,149, 150 nifedipine in symptomatic dermographism/urticaria factitia 151 and colchicine and indomethacin in delayed pressure urticaria.152, 153 However, more research may be needed for patient subgroups, for example recently Ref.154 a pilot study of patients with elevated D-dimer levels showed heparin and tranexamic acid therapy may be effective.

| Could any other treatment options be recommended as third-line treatment in urticaria? | ||

| We cannot make a recommendation with respect to further treatment options. (evidence-based and consensus-based) | 0 | > 90% consensus |

5.6 Treatment of special populations

5.6.1 Children

Many clinicians use first-generation, sedating H1-antihistamines as their first choice in the treatment of children with allergies assuming that the safety profile of these drugs is better known than that of the modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines due to a longer experience with them. Also, the use of modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines is not licensed for use in children less than 6 months of age in many countries while the recommendation for the first-generation H1-antihistamines is sometimes less clear as these drugs were licensed at a time when the code of good clinical practice for the pharmaceutical industry was less stringent. As a consequence, many doctors choose first-generation antihistamines which, as pointed out above, have a lower safety profile compared with modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines. A strong recommendation was made by the panel to discourage the use of first-generation antihistamines in infants and children. Thus, in children, the same first-line treatment and up-dosing (weight and age adjusted) is recommended as in adults. Only medications with proven efficacy and safety in the paediatric population should be used. Cetirizine,155 desloratadine,156, 157 fexofenadine,158 levocetirizine,159 rupatadine,160 bilastine161 and loratadine155 have been well studied in children, and their long-term safety has been well established in the paediatric population. In addition, the choice of the modern 2nd-generation H1-antihistamines in children depends on the age and availability as not all are available as syrup or fast dissolving tablet suitable for children. The lowest licensed age also differs from country to country. All further steps should be based on individual considerations and be taken carefully as up-dosing of antihistamines and further treatment options are not well studied in children.

| Should the same treatment algorithm be used in children? | ||

| We suggest using the same treatment algorithm with caution in children with chronic urticaria. (consensus-based) | ↑ | > 90% consensus |

5.6.2 Pregnant and lactating women

The same considerations in principle apply to pregnant and lactating women. In general, use of any systemic treatment should generally be avoided in pregnant women, especially in the first trimester. On the other hand, pregnant women have the right to the best therapy possible. While the safety of treatment has not been systematically studied in pregnant women with urticaria, it should be pointed out that the possible negative effects of increased levels of histamine occurring in urticaria have also not been studied in pregnancy. Regarding treatment, no reports of birth defects in women having used modern 2nd-generation antihistamines during pregnancy have been reported to date. However, only small sample size studies are available for cetirizine162 and one large meta-analysis for loratadine.163 Furthermore, as several modern 2nd-generation antihistamines are now prescription free and used widely in both allergic rhinitis and urticaria, it must be assumed that many women have used these drugs especially in the beginning of pregnancy, at least before the pregnancy was confirmed. Nevertheless, as the highest safety is mandatory in pregnancy, the suggestion for the use of modern 2nd-generation antihistamines is to prefer loratadine with the possible extrapolation to desloratadine and cetirizine with a possible extrapolation to levocetirizine. All H1-antihistamines are excreted in breast milk in low concentrations. Use of second-generation H1-antihistamines is advised, as nursing infants occasionally develop sedation from the old first-generation H1-antihistamines transmitted in breast milk.

The increased dosage of modern 2nd-generation antihistamines can only be carefully suggested in pregnancy as safety studies have not been carried out, and with loratadine it must be remembered that this drug is metabolized in the liver which is not the case for its metabolite desloratadine. First-generation H1-antihistamines should be avoided.100 The use of omalizumab in pregnancy has been proven to be safe and to date there is no indication of teratogenicity.164-166 All further steps should be based on individual considerations, with a preference for medications that have a satisfactory risk-to-benefit ratio in pregnant women and neonates with regard to teratogenicity and embryotoxicity. For example, ciclosporin, although not teratogenic, is embryo-toxic in animal models and is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight in human infants. Whether the benefits of ciclosporin in CU are worth the risks in pregnant women will have to be determined on a case-by-case basis. However, all decisions should be re-evaluated according to the current recommendations published by regulatory authorities.

| Should the same treatment algorithm be used in pregnant women and during lactation? | ||

| We suggest using the same treatment algorithm with caution both in pregnant and lactating women after risk-benefit assessment. Drugs contraindicated in pregnancy should not be used. (consensus-based) | ↑ | >90% consensus |

6 NEED FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The panel and participants identified several areas in which further research is needed. These points are summarized in Table 8.

|

| Intervention | Substance (class) | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Widely used | ||

| Antidepressant | Doxepina | CSU |

| Diet | Pseudoallergen-free dietb | CSU |

| H2-antihistamine | Ranitidine | CSU |

| Immunosuppressive |

Methotrexate Mycophenolate mofetil |

CSU ± DPUc Autoimmune CSU |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist | Montelukast | CSU, DPU |

| Sulphones | Dapsone, Sulphasalazine |

CSU ± DPU CSU ± DPU |

| Infrequently used | ||

| Anabolic steroid | Danazol | Cholinergic urticaria |

| Anticoagulant | Warfarin | CSU |

| Antifibrinolytic | Tranexamic acid | CSU with angioedema |

| Immunomodulator |

IVIG Plasmapheresis |

Autoimmune CSU Autoimmune CSU |

| Miscellaneous |

Autologous blood/serum Hydroxychloroquine |

CSU CSU |

| Phototherapy | Narrow-band UV-B | Symptomatic dermographism |

| Psychotherapy | Holistic medicine | CSU |

| Rarely used | ||

| Anticoagulant | Heparin | CSU |

| Immunosuppressive |

Cyclophosphamide Rituximab |

Autoimmune CSU Autoimmune CSU |

| Miscellaneous |

Anakinra Anti-TNF-alpha Camostat mesilate Colchicine Miltefosine Mirtazapine PUVA |

DPU CSU ± DPU CSU CSU CSU CSU CSU |

| Very rarely used | ||

| Immunosuppressive | Tacrolimus | CSU |

| Miscellaneous |

Vitamin D Interferon alpha |

CSU CSU |

- a Has also H1- and H2-antihistaminergic properties.

- b Does include low histamine diet as pseudoallergen-free diet is also low in histamine.

- c Treatment can be considered especially if CSU and DPU are coexistent in a patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank physicians and specialists who contributed to the development of this revision and update of the guidelines by active participation in the democratic process and discussion within the 5th International Consensus Meeting on Urticaria 2016. They want to express their thanks to all national societies for funding their delegates, and the following societies especially for the additional financial contribution to meeting costs and methodological research work: EAACI, EADV, EDF, GA2LEN, WAO. They also thank Tamara Dörr for her substantial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and the GA2LEN-UCARE-Network (www.ga2len-ucare.com) for scientific support.

Endorsing societies: AAAAI, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (endorsing with comments); AAD, American Academy of Dermatology; AAIITO, Italian Association of Hospital and Territorial Allergists and Immunologists; ACAAI, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; AEDV, Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; APAAACI, Asia Pacific Association of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology; ASBAI, Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunopathology; ASCIA, Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy; BAD, British Association of Dermatologists; BSACI, British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology; CDA, Chinese Dermatologist Association; CMICA, Mexican College of Clinical Immunology and Allergy; CSACI, Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; DDG, German Society of Dermatology; DDS, Danish Dermatological Society; DGAKI, German Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; DSA, Danish Society for Allergology; DST, Dermatological Society of Thailand; EAACI, European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; EMBRN, European Mast Cell and Basophil Research Network; ESCD, European Society of Contact Dermatitis; GA²LEN, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; IAACI, Israel Association of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; IADVL, Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists; JDA, Japanese Dermatological Association; NVvA, Dutch Society of Allergology (the official delegate agreed with the guideline but at time of publication the official letter of endorsement was not received. If received later an update will be published on the GA²LEN website.); MSAI, Malaysian Society of Allergy and Immunology; ÖGDV, Austrian Society for Dermatology; PSA, Polish Society of Allergology; RAACI, Russian Association of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; SBD, Brazilian Society of Dermatology; SFD, French Society of Dermatology; SGAI, Swiss Society for Allergology and Immunology; SGDV, Swiss Society for Dermatology and Venereology; SIAAIC, Italian Society of Allergology, Asthma and Clinical Immunology; SIDeMaST, Italian Society of Medical, Surgical and Aesthetic Dermatology and Sexual Transmitted Diseases; SPDV, Portuguese Society of Dermatology and Venereology; TSD, Turkish Society of Dermatology; UNBB, Urticaria Network Berlin-Brandenburg; UNEV, Urticaria Network; WAO, World Allergy Organization.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This are only the COI of the first author. Please refer to the table in the Method's paper where the COI of all authors are listed in detail