Incidence, mortality, survival, and disease burden of breast cancer in China compared to other developed countries

Abstract

Breast cancer was the most diagnosed malignant neoplasm and the second leading cause of cancer mortality among Chinese females in 2020. Increased risk factors and widespread adoption of westernized lifestyles have resulted in an upward trend in the occurrence of breast cancer. Up to date knowledge on the incidence, mortality, survival, and burden of breast cancer is essential for optimized cancer prevention and control. To better understand the status of breast cancer in China, this narrative literature review collected data from multiple sources, including studies obtained from the PubMed database and text references, national annual cancer report, government cancer database, Global Cancer Statistics 2020, and Global Burden of Disease study (2019). This review provides an overview of the incidence, mortality, and survival rates of breast cancer, as well as a summary of disability-adjusted life years associated with breast cancer in China from 1990 to 2019, with comparisons to Japan, South Korea, Australia and the United States.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2020, breast cancer became the most commonly diagnosed malignant neoplasm and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1 A total of 2.3 million people were diagnosed with breast cancer, representing 11.7% of all new cancers in both sexes, and 685,000 people died, representing 6.9% of all cancer mortality.1 According to the Global Cancer Observatory, breast cancer incidence rates were the highest in Australia and New Zealand, Western Europe, Northern America, Northern and Southern Europe, and Polynesia with age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR) greater than 70 per 100,000 women.2 Alternatively, Asian countries have demonstrated the lowest ASIRs.2 The breast cancer mortality data also showed significant geographic variations, with age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) being the highest among women in Melanesia (27.5/100,000), Polynesia (22.3/100,000) and Western Africa (22.3/100,000), and the lowest in Eastern Asia (9.8/100,000).1

As the largest and most populated upper-middle-income country, China has experienced a growing number of breast cancer cases.3 This may be attributed to a change in prevalence of certain risk factors of breast cancer, as well as rapid urbanization and widespread adoption of westernized lifestyles.3 Notably, in 2020, 416,371 Chinese women were diagnosed with breast cancer, contributing to 18% of the total number of new breast cancer cases worldwide.2, 3 However, the actual cancer burden in China may be underestimated due to the more limited coverage of cancer registries compared to some other countries: there were 574 registries throughout the country in 2019, covering 31.5% of the total population in China,4 compared to almost 100% in Australia.5 This deficit may affect the accurate interpretation of the burden of breast cancer in China. However, it should also be noted that these cancer registries are widely distributed across China. They cover populations from urban and rural areas, and from eastern, central, and western regions containing varying levels of economic development, which ensures a reasonable representative sample of the entire Chinese population, especially as the quality of registry data has improved.6 Besides, using statistical modeling such as Bayesian methods and Moran's I statistics, the temporal and spatial changes can still be proposed to facilitate informing prevention and treatment strategies.

The purpose of this narrative literature review is to provide an overview of the status of breast cancer in China in terms of incidence, mortality, survival, and disease burden. Temporal and geographic trends will be described and compared to data from Japan, South Korea, Australia and the United States. Urban-rural disparities will also be explored as well as the breast cancer burden in China represented by disability-adjusted life years (DALY).

2 INCIDENCE

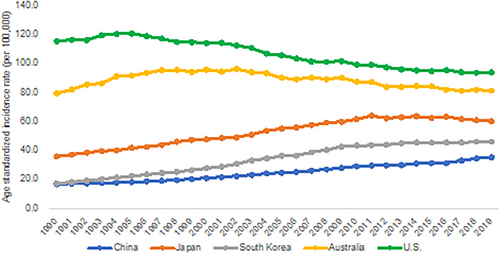

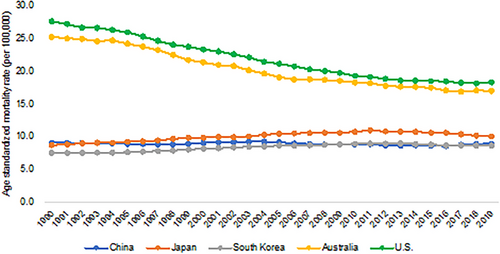

The incidence rate of breast cancer in China has been on an upward trend since 1990, similar to that in other Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea (Figure 1).7, 8 This may be attributed to the adoption of westernization practices in Asian countries.3 In particular, it is of note that despite limited access to national data before 1990 in China, regional records from the Shanghai Cancer Registry, one of the oldest cancer registries in China, revealed an increase in ASIRs among females living in urban Shanghai from 1973 to 2012, thus aligning to national trends.9 However, these increases contrast with what is reported in Australia and the United States, where ASIRs have steadily declined after around 1995 (Figure 1).

Despite the increasing trend, the ASIR in China remains relatively low compared to Japan and South Korea, Australia and the United States (Figure 1).7, 8 For example, in 2019, the ASIRs among women in Japan (60.5/100,000), South Korea (46.4/100,000), Australia (81.5/100,000), and the United States (94.2/100,000) were 1.3 to 2.6 times higher than that in China (35.6/100,000).7

2.1 Incidence of breast cancer by age

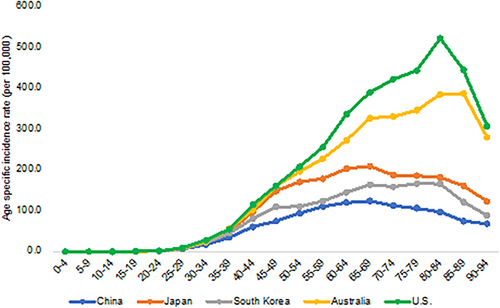

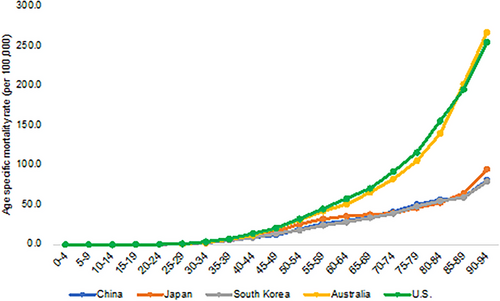

Compared with women in westernized countries, the peak age of breast cancer incidence is 10 years or more earlier among Chinese females (Figure 2).7, 8 Specifically in 2019, the highest age-specific incidence rate in China was 123.7/100,000 observed among women in the 65–69-year-age group, compared to 521.4/100,000 and 386.8/100,000 in 80–84 and 85–89 years old based in the United States and Australia, respectively. This dissimilarity was also shown with the onset age,10 with the medium age at diagnosis in China (46 years in 2013–2017) being over 10 years earlier than that in Australia (63 years in 2017), United States (63 years in 2014–2018) and Japan (60 years in 2017).11-14 Like China, South Korea also reported an early onset age of 52 years in 2018.15

It is important to note however that the peak age of incidence has been gradually shifting to older ages in China.16 Although, as mentioned above, incidence rates are relatively low before the age of 20, and then increase significantly and plateau in the fifth or sixth decade, the peak age group has moved from 50–54 in 200817 to 55–60 in 2013,18 and 65–69 years in 2019.7 Keeping with national trends, regional records of age-specific incidence from Shanghai,19 Wuhan,20 and Hong Kong Special Administration Region (SAR)21 show similar patterns and have reported a 10- to 15-year time shift toward older ages within the last 20 years.

2.2 Urban-rural disparity of incidence

Administratively, urban areas in China are defined as the areas where the local governments of the county (xian) level and above are situated, and the rural areas are the places governed by village authorities (xiang).22 Under these definitions, urban areas are composed of “districts in cities” (chengqu), and “districts in towns” (zhenqu), which are usually located in the center of a city and the surrounding suburbs, respectively.22 Rural areas are remote from the city districts, with less population and under-developed infrastructures, which people residing in are mainly involved in agricultural activities, provided with fewer social and healthcare benefits, and have a lower income compared to those living in urban places.23

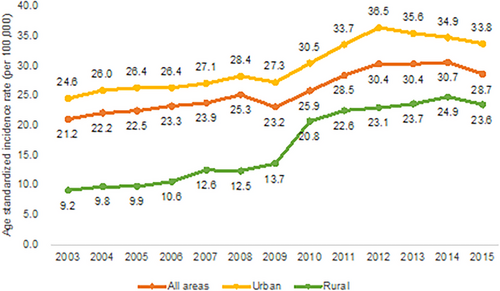

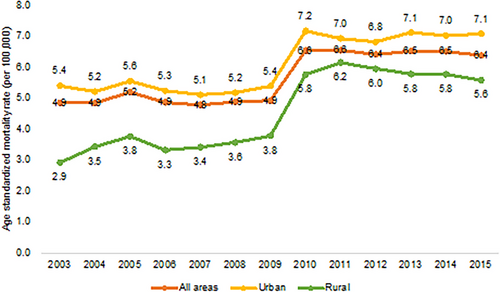

Sourced from the National Central Cancer Registry of China, studies have revealed an incidence disparity among women between urban and rural areas, with ASIRs being higher in urban regions (Figure 3).17, 18, 24-29 However, a reduction in this regional discrepancy was observed after 2009 due to the significant increase in incidence rates in rural areas, which may be attributable to the implementation of a free breast screening program in rural regions since 2009, leading to an increase in early detection and diagnosis of breast cancer.30 The recent rural increases may also be attributable to the policy of the public health system which requires rural migrant workers who are diagnosed with breast cancer after being exposed to high risk factors in the city to register as a rural patient in their hometown.31

Geographical disparity in the incidence rate of breast cancer was also demonstrated across regions in China, in line with socioeconomic development and industrialization.31 Specifically, the average incidence rates during 2010–2015 in the eastern, central, and western regions (divided according to the National Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbook) were 47.7/100,000, 35.0/100,000 and 29.1/100,000, respectively.32 The higher prevalence of risk factors for breast cancer due to westernized practices, and the higher detection rate of breast cancer due to the greater accessibility to medical resources in the eastern region compared to the central and western regions could be possible explanations for this geographical disparity.31, 33

3 MORTALITY

The ASMR of breast cancer in China showed a slightly ascending trend from 1990 to 2019, not dissimilar to that of Japan and South Korea (Figure 4).7, 8 However, this is in contrast to Australia and the United States, where numbers have steadily declined (Figure 4).7, 8 The decline in these two countries has been suggested to be attributable to increased awareness of breast cancer and concomitant reductions in breast cancer risks, increased adoption of mass breast screening programs, and better treatments.34 Furthermore, the adoption of digital mammography and classification of breast cancer by molecular expression in the early twenty-first century have further contributed to the reduction of mortality rates by increasing sensitivity in detecting cancer and improving personalized treatment through molecular subtyping.35

Regional trends within China demonstrate a similarity to national data: the Shanghai Cancer Registry showed a 26.6% increase in ASMR in females living in urban Shanghai from 1973 to 2012,9 and the Jiangsu Cancer Registry recorded an increase from 10.6/100,000 to 23.4/100,000 during 2003–2011.36 It is interesting to note that ASMRs in Hong Kong SAR remained nearly stable or decreased slightly between 1991 and 2018,21 possibly resulting from the adoption of the guidelines for surgeons published in 1995 in the United Kingdom focused on the treatment of symptomatic breast cancer, which improved diagnosis and treatment services.37

The ASMR of breast cancer is lower in China compared to that of Australia and the United States, while being similar to that of Japan and South Korea (Figure 4).7, 8 In 2019, the ASMRs in China (9.0/100,000), Japan (10.1/100,000), and South Korea (8.7/100,000) were almost half of those in Australia (17.1/100,000) and the United States (18.4/100,000). The relatively low mortality rates in Asian countries are at least partly due to the lower incidence rates compared to those in Australia and the United States.

3.1 Breast cancer mortality by age

Similarly to incidence, breast cancer mortality is highly associated with age (Figure 5).7, 8 Generally, the mortality rate of breast cancer increases with age, being the lowest in women under 35 years and the highest in those over 85 years of age in all countries. Before 50–54 years, the mortality rates of breast cancer are almost the same across countries, after which, the mortality risks are divergent, with figures in Australia and the United States increasing substantially compared to a slight increase in China, Japan, and South Korea. This disparity could be explained by the two-disease model of breast cancer, where premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancers are hypothesized to be two diseases with different pathological mechanisms.38 The “two” diseases themselves demonstrate mortality rates that are different but overlapping in terms of age distribution.38 The relatively high mortality rates after 55 years in Australia and the United States may be due to a higher proportion of post-menopausal breast cancer compared to Asian countries (82.6% in North America, 78.2% in the Australia and New Zealand region, and 64.6% in Eastern Asia).39 Furthermore, this disparity may be related to a higher prevalence of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in Western than Asian populations. Because the HRT is suggested to increase the risks of breast cancer in post-menopausal women, especially those on combined estrogen/progestin therapy for more than 5 years.40 Studies have reported that the proportion of women who used HRT was 2.1% (2012) and 6.3% (2013) in China and South Korea, respectively,41, 42 compared to 24% (2013) in Australia.43 However, more comparative studies are needed to investigate the impact of HRT consumption patterns, including estrogen alone versus combined estrogen/progestin therapy, dose and administration method, and treatment duration, on breast cancer development among post-menopausal females from Asian and Western countries.

3.2 Urban–rural disparity of mortality

The urban–rural disparity in breast cancer mortality was in line with the geographical distribution of incidence rates in China, with mortality rates higher among women in urban than in compared to other rural areas during 2003 and 2015 (Figure 6).17, 18, 24-29 Other location-dependent variations in mortality rates have been demonstrated, with higher numbers in the southwest compared to northeast China, and in the west compared to eastern and southeastern coastal China.32

4 SURVIVAL

4.1 Survival difference between China and other countries

The breast cancer survival rate is relatively low in China compared to other developed countries. The age standardized 5-year relative survival rate was 82% for breast cancer consumers diagnosed in 2012–2015 in China, compared to that recorded in Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the United States where 5-year relative survival rates exceeded 90% for a similar time period (Table 1).12, 44-47 Despite a relatively low survival rate, breast cancer outcomes are improving in China.44 Specifically, the 5-year relative survival rate of breast cancer increased from 73.1% to 82.0% for patients diagnosed in 2003–2005 and 2012–2015 (Table 1).44 This could be partially due to the national medical reform initiated in 2009, and since then Basic Medical Insurance (BMI) expanded its coverage and the national reimbursement drug list (NRDL) subsidized more essential anticancer drugs.48 In particular, 95% of all residents of China were covered under BMI in 2011.48

| Country | Period of diagnosis | 5-year relative survival (%) | Period of diagnosis | 5-year relative survival (%) | Period of diagnosis | 5-year relative survival (%) | Period of diagnosis | 5-year relative survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 2003–2005 | 73.1% | 2006–2008 | 78.9% | 2009–2011 | 79.7% | 2012—2015 | 82.0% |

| Japan | 2000—2002 | 87.7% | 2003–2005 | 89.1% | 2006–2008 | 91.1% | 2009—2011 | 92.3% |

| South Korea | 1993–1995 | 79.2% | 2006–2010 | 86.6% | 2011–2015 | 92.3% | 2013–2017 | 93.2% |

| Australia | 1998–2002 | 86.4% | 2003–2007 | 88.4% | 2008–2012 | 89.8% | 2013–2017 | 91.5% |

| U.S. | 1996–1998 | 88.2% | 1999–2002 | 89.9% | 2003–2009 | 90.3% | 2011–2017 | 90.3% |

Delayed diagnosis and subsequent late stages at presentation are related to poor breast cancer survival. Unlike populations in some developed countries where a high percentage of breast cancer diagnoses occur in the early stages mainly attributable to breast screening, some Chinese women are commonly not taking advantage of breast screening or do not recognize and respond quickly to breast changes.49 This could be due to insufficient cancer awareness,50-52 breast cancer fatalism, the stigma of having the disease,53-56 financial concern,52, 57 and inaccessibility of screening and diagnostic facilities in less economically developed regions,30, 52 which has resulted in a high proportion of females being diagnosed in late stages.58

Cross-sectional surveys reported that Chinese women lacked a detailed understanding of breast cancer-related symptoms, risk factors, and detection methods.50-52 Although most of them understand that breast cancer is common and breast lumps and family history are strongly related to this disease, only around half of the women in the study know other atypical symptoms (e.g., nipple discharge and axillary lump) and risk factors (e.g., a high-fat diet, early menarche and late menopause).50-52 Regarding cancer detection methods, up to 80% of surveyed women are unaware of the benefits of mammography, which at least partially explains the low utilization rate of breast screening in China (22.5% for women aged 35–69 years in 2013).49, 52

Fatalism and stigma are also related to the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer.53-56 In China, some people believe that cancer development and progression are predetermined by external forces and that personal intervention will not alter health outcomes.55, 56 This fatalistic view negatively affects patients’ health practices, leading to avoidance of breast screening participation, in-adherence to medical treatment, and thus poor outcomes.56 Furthermore, people are often stigmatized for having breast cancer, making them reluctant to attend breast screening and delay hospital visits. The stigma often arises from the beliefs in Buddhism that treat cancer as a punishment for the misdeeds of patients or their ancestors, and traditional Chinese medicine that attributes breast cancer to negative personalities, such as jealousy and narrow-mindedness; or traditional Chinese philosophies that associate breast cancer with immoral behaviors.53, 55

The Chinese health authority has launched several breast cancer screening programs. In 2012–2013, a breast screening program was launched, targeting high-risk urban females residing in 14 selected cities from nine provinces in China.59 Since 2009, a “two cancers” screening program was implemented, providing government-funded breast and cervical cancer screening for rural and economic-disadvantaged urban females aged 35–64 years and at average risk.30 Despite being free, the reported attendance rate is still low (22.5% for women aged 35–69 years in 2013).49 One of the underlying reasons is insufficient medical resources, such as a shortage of general practitioners, mammography, and screening facilities.30 Studies revealed that people are unwilling to attend if the screening site is far away from where they live.30 It is also worth noting that the coverage of the free “two cancers” screening program is limited, and the nontargeted population needs to pay out-of-pocket, which raises financial concerns, leading to delayed diagnosis.52

Effective and systematic management of breast cancer plays a significant role in preventing recurrence and metastasis and prolonging survival. In recent years, molecular targeted therapy, including inhibitors of endocrine and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), has transformed conventional breast cancer treatment with reduced toxicity, improved response rates to treatment, and a better prognosis.60 However, in China, the use of targeted therapy was partially affected by the unaffordability of patent anticancer drugs that were not covered by medical insurance.61, 62 A 2013–2014 nationwide survey on the clinical use of a HER2-targeted drug called trastuzumab found that less than 30% of HER2-positive breast cancer patients received post-surgery adjuvant treatment that included trastuzumab.61 In particular, the underuse of trastuzumab was more prominent in the less developed regions of China,62 this was at least partially due to the high cost of trastuzumab, which was not included in the NRDL until 2017.48 Although listed in NRDL, by 2018 only eight provinces had trastuzumab on their local reimbursement drug list (LRDL).48 In comparison, the uptake rate of trastuzumab in breast cancer adjuvant therapy has been higher in Australia and New Zealand region and the United States, ranging from 72% to 80.9%.63

The out-of-pocket medical expenses are still substantial even if using the anticancer drugs covered by LRDL, given the high and increasing launch prices and the long-term treatment after cancer diagnosis.64 The Chinese cancer survivors spent approximately 48% and 288% of the average monthly income on generic and patented anticancer pharmaceuticals, respectively.65 The antibreast cancer drugs cost even more, placing a severe financial burden on cancer patients.65 Compared to developed countries, financial hardship is heavier among Chinese cancer patients, although the retail prices of anticancer drugs are lower in China.65 For example, in Australia, the monthly expenses of generic and patented anticancer drugs account for 3% and 71% of the average monthly income, respectively.65 The lower affordability of cancer treatment may be attributable to the lower per capita spending power in China than that in westernized countries.65 Besides, the abuse of traditional Chinese medicine adds to the financial burden of Chinese cancer patients. Since it is reported that some patients rely on traditional Chinese drugs in addition to western medicine to cure cancer; however, the actual benefits of these traditional Chinese drugs are largely unproven.64 The considerable financial burden negatively affects their medical adherence, mental health, and quality of life.64, 65 Patients with heavier financial difficulties are more likely to quit treatment or reduce the prescribed amount of medication, suffer a mental disorder, and reduce daily necessities expenditures.64

4.2 The urban–rural disparity in survival

Adapted to incidence and mortality, there are also urban–rural disparities in breast cancer survival. For women diagnosed in 2012–2015, the 5-year relative survival of breast cancer was 84.9% and 72.9% in urban and rural areas, respectively.44 The underlying reason for this discrepancy is multifaceted, including but not limited to lower breast screening participation, more difficulty in accessing tertiary hospitals, and lower reimbursement rates in rural than urban populations.66, 67 Rural females demonstrated a greater reluctance to pay and attend screening, which might have led to more delayed diagnoses and undesired prognoses compared to urban females.67 Although several free breast screening programs have been introduced for rural and urban women since 2009 and 2013, respectively, the coverage was limited and to date, free screening has not yet completely addressed the urban-rural participation gap.68 Regarding the accessibility of tertiary hospitals, rural women had more difficulty accessing urban tertiary hospitals, which are generally better equipped with diagnostic equipment and qualified health providers than rural local hospitals, thus influencing breast cancer outcomes.66, 67 Additionally, rural residents receive a lower reimbursement rate than their urban counterparts who are covered by different BMI schemes.66 Specifically, rural people are under the New Rural Cooperative Medical System which receives a 44% inpatient reimbursement, while urban residents receive a 48%−68% inpatient reimbursement under Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance or Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance.66

5 OVERALL BURDEN OF BREAST CANCER

DALY is an effective tool to quantify the burden of disease in populations taking into account both fatal and nonfatal health outcomes.69 This measurement is calculated by combining years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality with years of life lived with disability (YLD), with one DALY representing the loss of one equivalent year of ideal health life.69 Understanding DALY of breast cancer, in addition to mortality rates, is necessary to comprehensively measure the actual burden of breast cancer among populations.2

According to Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019), the absolute values of DALY increased in all countries from 1990 to 2019, with the highest value being observed in China (Figure S1).7, 8 This increase ranged from 5% to 138%, among which South Korea (138%) and China (106%) experienced the most rapid escalation, while Australia (26%) and the United States (5%) remained almost stable. Due to the steep increase and the highest starting point of DALY, by 2019 the burden of breast cancer in China became 2–32 times higher compared to the other four countries.

Trends with YLLs and YLDs are in line with that of DALYs, with YLLs being the predominant component of the burden of breast cancer (Figures S2–S3).7 Specifically in China, 91% of DALYs came from YLLs and 9% from YLDs in 2019. However, there is a gradual shift of the cancer burden toward nonfatal disabilities in all these countries since 1990 (Figure S4). This change may be in part due to the widespread acceptance of breast screening coupled with the improvement in breast cancer treatment. These interventions have helped find more cancer cases at curable stages, thus prolonging the survival time and reducing the number of premature deaths.34 However, the effect of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer should also be taken into consideration in the interpretation of the trends.34

Age-specific DALY of breast cancer showed that the peak age occurred in 50–54 years in China in 2019, around 5 to 15 years earlier compared to that of Australia, the United States, and its neighboring countries Japan and South Korea (Figure S5).7 This is in line with the age-specific incidence and mortality, which can be attributable to the early onset age of breast cancer in the Chinese population compared to their western counterparts. However, a shift in the peak age of DALYs to older ages was noticed in China, with the most rapid increase in women aged 65 years and above.70 Considering the aging population in China, the burden of breast cancer will become heavier, which prompted measures to prevent the occurrence of breast cancer.

6 MAIN FINDINGS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This study reviewed the increasing burden of breast cancer in China and highlighted the urban-rural disparities in breast cancer incidence, mortality, and survival. The rising incidence rate of breast cancer suggests an increasing prevalence of risk factors among Chinese women. To advance people's health awareness, campaigns can be run to educate women regarding risk factors, early signs and symptoms, and detection methods of breast cancer, and to promote a healthy lifestyle. This study also revealed a lower survival rate of breast cancer among rural residents compared to their urban counterparts. This survival discrepancy is largely due to the suboptimal utilization of medical resources that can be attributed to the lack of healthcare resources and financial support in rural places.57 The lack of medical facilities and specialists in less developed rural areas is a barrier to cancer screening and medical assistance, and most rural cancer patients are diagnosed after developing symptoms.57 Additionally, the high costs of medical services discourage them from seeking medical services, and some rural residents delay treatment after cancer diagnosis due to a lack of financial supports.57 To ensure that every patient can receive proper health care, the Chinese health authorities could address the shortage of medical facilities, screening sites, and medical specialists in rural places, prioritize financial allocation, and provide more public insurance reimbursements to disadvantaged rural residents. Also, ongoing efforts should be made to include more generic and patented anti-cancer medications in NRDL through negotiation to increase drug availability and reduce the financial toxicity for cancer patients in China.

Although this review found that the incidence, mortality, and survival rates of breast cancer are higher in urban than rural areas, and in eastern than central and western China, the impact of other factors, including socioeconomics, educational attainment, occupation, and ethnicity, on the occurrence and development of breast cancer among Chinese females is under-investigated. This is predominately due to the inaccessibility of sufficient demographic data. Limited studies have suggested that income, education, profession, and ethnicity could influence an individual's knowledge of breast cancer, attitudes toward cancer screening, and thus cancer diagnosis, staging, and treatment.71 Liu et al. found that patients with lower income and educational levels were more likely to be diagnosed in advanced stages with larger tumor sizes due to a lack of awareness of early signs of breast cancer.72 However, a higher incidence rate was observed among those with higher educational attainment, which may be attributable to their high risk lifestyles such as nulliparity and short breastfeeding time.72 Li et al. indicated that certain occupation-related risk factors such as night shift work increased the likelihood of breast cancer, suggesting that changes in sleep patterns would affect estrogen secretion and receptor function, leading to the occurrence of breast cancer.73 Additionally, studies focusing on ethnic minorities revealed that women from different ethnic groups may display various genotypes that determine treatment responses.74 However, research is still limited in such disparities such as socioeconomic status, educational attainment, occupation, and ethnicity. More studies are needed to reveal the variations in breast cancer profile in different population groups to better allocate medical resources and cancer prevention.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Breast cancer is a significant public health issue in China. The incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer have been increasing since the beginning of the twentieth century. Despite the rates being relatively lower compared to those in other developed countries, the actual number of new cases and deaths has been considerable, placing a heavy burden on the finance and healthcare systems in China. The incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer have been higher in urban than rural areas of China, and these urban-rural gaps have narrowed since around 2010. This may reflect geographic variations in breast cancer risk factors and the accessibility of breast cancer early detection and treatment methods. Although breast cancer survival is comparatively lower in China compared to some other developed countries, improvements are attributable to wider coverage of the health system and insurance and advances in treatment and management. However, as with incidence and mortality, an urban-rural survival disparity is again present, highlighting the need to ensure adequate distribution of medical resources and equal access to medical care.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The research team would like to acknowledge that they received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created in this study.