The management of clinically suspicious para-aortic lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer: A systematic review

Abstract

Approximately 1%–2% of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) develop para-aortic lymph node (PALN) metastases, which are typically considered markers of systemic disease, and are associated with a poor prognosis. The utility of PALN dissection (PALND) in patients with CRC is of ongoing debate and only small-scale retrospective studies have been published on this topic to date. This systematic review aimed to determine the utility of resecting PALN metastases with the primary outcome measure being the difference in survival outcomes following either surgical resection or non-resection of these metastases. A comprehensive systematic search was undertaken to identify all English-language papers on PALND in the PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar databases. The search results identified a total of 12 eligible studies for analysis. All studies were either retrospective cohort studies or case series. In this systematic review, PALND was found to be associated with a survival benefit when compared to non-resection. Metachronous PALND was found to be associated with better overall survival as compared to synchronous PALND, and the number of PALN metastases (2 or fewer) and a pre-operative carcinoembryonic antigen level of <5 was found to be associated with a better prognosis. No PALND-specific complications were identified in this review. A large-scale prospective study needs to be conducted to definitively determine the utility of PALND. For the present, PALND should be considered within a multidisciplinary approach for patients with CRC, in conjunction with already established treatment regimens.

1 INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer globally and has the fourth highest mortality rate.1, 2 Up to 30% of patients with CRC develop distant metastases, most commonly in the liver or lung.1 Approximately 1%–2% develop para-aortic lymph node (PALN) metastases. The development of PALN metastases is considered to constitute systemic disease, in accordance with the classification system from the American Joint Committee on Cancer, which classifies these as M1b disease. PALN metastases are associated with a poor prognosis with a reported mean overall survival (OS) ranging from 3 – 33 months, even with systemic palliative therapy.3-5

The treatment options for isolated CRC liver and lung metastases include surgical metastasectomy and chemotherapy, which in combination, have improved 5-year OS to approximately 30%–50%.2 However, there is currently a paucity of research on the utility of resecting PALN metastases in patients with CRC given that these are generally considered markers of underlying systemic disease.3, 6 Palliative chemotherapy is therefore the usual mainstay of treatment for PALN metastases, with a 5-year OS of approximately 30% reported in literature following treatment.6 To date, several case series have reported favourable outcomes in patients who have undergone PALN dissection (PALND), but these studies have predominantly been small-scale and retrospective in nature.

This review aims to better determine the utility of PALND, with a focus on developing a better understanding of the treatment algorithm associated with this procedure, the criteria for patient selection, and of its impact on prognosis and subsequent survival.

2 METHODS

2.1 Search strategy

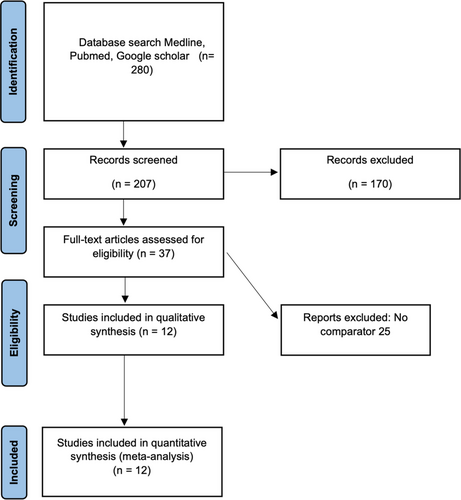

A systematic search was undertaken in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines to identify relevant studies in the PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar databases. A detailed search strategy was performed. The keywords used in combination for the search were as follows: “PALND”, “extended lymph node dissection”, “retroperitoneal lymph node”, and “colorectal lymph node metastasis”. The search, review, and data extraction were performed by two independent authors (Michelle Zhiyun Chen and Joseph C Kong). Any discrepancy in the inclusion or exclusion of a study or data was independently reviewed by Yeng Kwang Tay. Additional studies were also included in the full-text review.

2.2 Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the difference in survival between surgical resection and non-resection of PALN metastases in CRC. Secondary outcome measures included the rate of post-operative complications, the rate of disease recurrence, disease-free survival (DFS), and OS. An R0 resection meant that there was no residual cancer at the resection margins while an R1 resection meant that there was microscopic residual cancer at the distal or circumferential resection margins.

2.3 Data extraction, inclusion and exclusion criteria

All English language studies reporting on at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes were included. Studies were excluded if there were no reported survival outcomes of patients undergoing PALND. Case reports, letters, editorials, expert opinions, and abstracts were also excluded.

3 RESULTS

The search results identified a total of 12 eligible studies for analysis. (Figure 1) All studies were either retrospective cohort studies or case series. (Tables 1–3)2, 3, 5-14

| Study | Year | Design | Country | Site of Primary | Study comparisons | Total patients | PALN diagnosis criteria | No. PALN +ve (histologically post-op) | Resection margins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous PALND | |||||||||

| Min et al.7 | 2009 | Case series | Korea | Rectum | Lateral LND 16 versus PALND 85 versus PALND + Lateral LND 50 | 151 |

|

43/135 |

133 R0 18 R1 |

| Bae et al.8 | 2016 | Case series | Korea | Colorectal |

Regional lymphadenectomy (RLND) 953 versus PALND 129 versus Liver metastasectomy 91 |

1082 |

|

49/129 | - |

| Song et al.9 | 2016 | Case series | Korea | Colorectal | PALND 40 | 40 |

|

16/40 | - |

| Ogura et al.1 | 2017 | Case series | Japan | Colorectal | PALND 16 versus palliative surgery/control group 12 | 28 |

|

15/16 |

16 R0 12 R1 |

| Ushigome et al.11 | 2020 | Cohort | Japan | Colorectal | PALND 16 versus PALND + metastasectomy 4 (one liver, two ovarian, and one peritoneal) | 20 |

|

20/20 | 20 R0 |

| Synchronous and metachronous PALND (sPALN and mPALN) | |||||||||

| Choi et al.2 | 2010 | Cohort | Korea | Colorectal |

PALND 24 (sPALN 19, mPALN 5) versus no surgery/control 53 |

77 |

|

24/24 | - |

| Gagniere et al.12 | 2015 | Case series | France | Colorectal | sPALN 19, mPALN 6 | 25 |

|

25/25 | 25 R0 |

| Arimoto et al.6 | 2015 | Case series | Japan | Colorectal | sPALN 9, mPALN 5 | 14 |

|

14/14 | 14 R0 |

| Metachronous PALND | |||||||||

| Shibata et al.13 | 2002 | Cohort | United States | Colorectal | PALND 20 versus no surgery/control 5 | 25 |

|

20/20 |

15 R0 5 R1 |

| Min et al.5 | 2008 | Cohort | Korea | Colorectal | PALND 6 versus no surgery/control 32 | 38 |

|

6/6 | 6 R0 |

| Dumont et al.3 | 2012 | Case series | France | Colorectal | PALND 23 versus Locoregional LND 8 | 31 |

|

- | 31 R0 |

| Kim et al.14 | 2020 | Cohort | Korea | Colorectal | PALND 16 versus no surgery/control 30 | 46 |

|

16/16 |

12 R0 4 R1 |

| Study | Year | Neoadjuvant therapy | Type of neoadjuvant therapy | Adjuvant therapy | Type of adjuvant therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous PALND | |||||

| Min et al.7 | 2009 | Chemoradiotherapy 19 | 5FU/leucovorin + concurrent radiation. (5040cGy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks) |

|

|

| Bae et al.8 | 2016 | - | - | Chemotherapy 937 (86.6%) | 5FU/leucovorin or FOLFOX for 6 months |

| Song et al.9 | 2016 | Chemoradiotherapy 7 | - | Chemotherapy 24 | 5FU/capecitabine |

| Ogura et al.10 | 2017 | Chemotherapy:

|

- | Chemotherapy:

|

Oxaliplatin or irinotecan |

| Ushigome et al.11 | 2020 | Chemotherapy 2 | Oxaliplatin | Chemotherapy 12 | Camptothecin-11 or oxaliplatin |

| Synchronous and metachronous PALND (sPALN and mPALN) | |||||

| Choi et al.2 | 2010 | Chemotherapy:

|

|

Chemotherapy:

|

|

| Gagniere et al.12 | 2015 |

|

5FU/leucovorin, folinic acid, oxaliplatin/irinotecan +/- cetuximab or bevacizumab | Chemotherapy 21 | 5FU+leucovorin, folinic acid, oxaliplatin/irinotecan +/- cetuximab or bevacizumab |

| Arimoto et al.6 | 2015 | Chemotherapy 9 | Oxaliplatin 3 months | Chemotherapy 6 | Oxaliplatin, oral 5FU |

| Metachronous PALND | |||||

| Shibata et al.13 | 2002 |

|

- |

|

- |

| Min et al.5 | 2008 | No surgery group:

|

|

No surgery group: 0 PALND group: Chemotherapy 6 |

5FU/leucovorin + oxaliplatin |

| Dumont et al.3 | 2012 |

|

|

Chemotherapy 23 (7LND, 1PALND) |

5FU/leucovorin + oxaliplatin + irinotecan + cetuximab or bevazizumab |

| Kim et al.14 | 2020 | No surgery group:

|

|

No surgery group: 0PALND group:

|

|

| Study | Year | Morbidity and Mortality (%) | Post op complications | Operative outcomes | Disease-free survival (DFS) | Overall survival (OS) | Follow up period | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous PALND | ||||||||

| Min et al.7 | 2009 |

|

41 patients: 15 urinary dysfunctions, six intestinal obstructions, five anastomotic leaks, six wound-related, respiratory-related, and four others | 5-year:

|

5-year:

|

- | - | |

| Bae et al.8 | 2016 |

|

|

5-year:

|

5-year:

|

Median follow-up 74.2 (1–179) months |

|

|

| Song et al.9 | 2016 |

|

PALND: Two anastomotic leaks, two ileuses, and two others |

|

3-year:

|

3-year:

|

Median follow-up 31 (9.1–103.1) months |

Nine recurrences (22.5%): five distant metastases, three PALN + distant metastasis, and one PALN only |

| Ogura et al.10 | 2017 |

|

|

Blood loss:

|

5-year: PALND 60.5% |

5-year: PALND 70.3% Palliative group 12.5% |

Median follow-up 4.9 (0.2–8.6) years | PALND 7 recurrences (43.8%): Two in PALN, one in PALN + lateral pelvic LN, one liver+PALN, one liver, one lateral pelvic LN, and one peritoneum |

| Ushigome et al.11 | 2020 | - | - | - | 5-year 25% | 5-year 39% | Median follow-up 24.8 (6.6–248.1) months | 17 recurrences (85%) |

| Synchronous and metachronous PALND (sPALN and mPALN) | ||||||||

| Choi et al.2 | 2010 | PALND:

|

|

- | PALND:

|

PALND:

|

PALND: Median follow-up 29 (7–75) months Control: Median follow up 28 (3–96) months |

PALND 16 recurrences (66.7%): Seven PALN and nine multiple organs |

| Gagniere et al.12 | 2015 | 8% morbidity | One pulmonary embolism and one right ureteric injury | Median length of stay 16 (7–23) days |

|

|

Median follow up 85 (4–142) months | 15 recurrences (60%) |

| Arimoto et al.6 | 2015 | 50% morbidity | One anastomotic leak, one bleeding, one ileus, and three others | - |

|

|

Median follow up 33.2 (4.3–50.6) months | 12 recurrences (85.7%) |

| Metachronous PALND | ||||||||

| Shibata et al.13 | 2002 | 28% morbidity | One abscess, one phlebitis, one pneumonia, one small bowel obstruction, and one bladder injury | - | PALND:

|

PALND:

|

Median follow up 29 (1–151) months | 12 recurrences(60%): 11 local, 1 distant metastases |

| Min et al.5 | 2008 | 33% morbidity | Two small bowel obstruction | - |

PALND: Mean 28 months, Median 21 months No surgery: Mean 18 months |

PALND: Median 34 months No surgery: Median 14 months |

Median follow up 30 months | 100% recurrence |

| Dumont et al.3 | 2012 | - | - | - |

Overall 3-year DFS 19% LND: 3-year 0% PALND: 3-year 26% |

|

Median follow up 47 (4–258) months |

27 recurrences (87%) |

| Kim et al.14 | 2020 | - |

|

Median follow up 50 (30–72) months | Eight recurrences (50%) | |||

3.1 Is there a difference in survival between patients undergoing curative treatment for PALN metastases and locoregional lymph node metastases?

Patients with PALN metastases or locoregional lymph node metastases typically undergo curative surgery with associated PALND or regional lymphadenopathy respectively. In a 2009 study comparing post-operative outcomes following such surgery with curative intent, Min et al. demonstrated that 5-year DFS was worse in patients with PALN metastases as compared to patients with locoregional lymph node metastases, with survival rates of 17.6% and 26.3% noted in the two groups respectively (p < .001).7

These findings were corroborated by Bae et al.’s 2016 study which also found that both OS and DFS were significantly better following curative surgery in patients with locoregional disease as compared to those with PALN metastases (5-year OS 75.1% vs. 33.9%, p < .001; 5-year DFS 66.2% vs. 26.5%, p < .001).8 The systemic recurrence rate was also significantly higher in the PALN metastasis group as compared to the locoregional metastasis group with rates of 59.1% versus 18.8%, p < .001.

However, Dumont et al.’s study focusing on central retroperitoneal recurrences had contrasting results. In this study of 31 patients which compared outcomes from patients who underwent a complete resection of either locoregional or PALN recurrence, patients with locoregional recurrence were noted to have a significantly worse OS (p = .033).3

3.2 Is there a difference in survival between patients undergoing curative treatment for PALN metastases and distant metastases?

Curative treatment for distant organ metastases generally includes the options of liver and lung metastasectomy. In their 2016 study, Bae et al. demonstrated comparable 5-year OS and DFS between patients who underwent PALND and those who underwent liver metastasectomy (OS 33.9% vs. 38.7%, p = .080; DFS 26.5% vs. 27.6%, p = .604 respectively).8

3.3 What is the risk of recurrence after PALND?

Ushigome et al.’s retrospective study studied the long-term outcomes for patients who underwent R0 resection of synchronous PALN metastases and distant metastases, finding a 5-year OS of 39%.11 The risk of recurrence was noted to be very high at 85%. Recurrences more than a year after PALND were mostly isolated nodal recurrences, adding weight to the theory that a longer time to recurrence may be more oncologically favourable, and may be associated with better long-term survival from a biological perspective. High rates of recurrence after PALND have also been published elsewhere in the literature, including in Nakai et al.’s large-scale retrospective study.15

The role of re-resection of recurrence after PALND has not been studied much, but Ushigome et al. hypothesise that it may be valuable to perform re-resection given findings from elsewhere in the literature about improved prognosis with re-resection of lymph node recurrence or repeat hepatic resection for liver re-recurrence.11

3.4 Is there a difference between synchronous versus metachronous PALND?

In this systematic review, studies comparing survival outcomes between synchronous and metachronous PALND were noted to rarely distinguish between the two groups.

Arimoto et al.’s study compared R0 synchronous and metachronous PALND and demonstrated that patients with synchronous metastasis had poorer OS than those with metachronous disease (p = .013), with aggressive chemotherapy noted not to alter survival outcomes.6 They reported a 3-year OS of 41.2% after PALND, with a 86% recurrence rate. Gagniere et al.12 also reported a similar 3-year OS of 64% with a 60% recurrence rate in their 2015 study.

The findings of improved OS with metachronous PALN metastases as compared to synchronous PALN metastases are further corroborated by Wong et al.’s systematic review which found 5-year OS to be 22%–34%, and 15%–60% in the synchronous and metachronous groups respectively.16

3.5 What is the impact on survival from PALND?

Several studies found a positive survival correlation with PALND as compared to the non-resection of PALN metastases in CRC.

In comparing patients who did and did not undergo PALND, both Kim et al. and Shibata et al. found survival to be statistically better with PALND (71 months vs. 39 months, p = .017 and 31 months vs. 3 months, p ≤ .001 respectively).13, 14 Wong et al.’s systemic review corroborated these findings, demonstrating a median OS of 34–40 months for patients who underwent PALND, as compared to just 3–14 months for patients who did not undergo surgery.16

Min et al. reported a median OS of 34 months for patients who underwent metachronous PALND as compared to just 14 months for patients who did not undergo resection (p = .034), but a poorer outcome was noted if both lateral pelvic lymph node and PALN metastases were present.5 Choi et al. also noted a higher 5-year OS survival of 53.5% (median 64 months) in patients who underwent synchronous PALND, as compared to 12% (medial 13 months) in the unresected group (p = .045).2

Survival was noted to be impacted by the degree of PALN disease, with Song et al. reporting a 3-year DFS of 55.6% in the presence of <4 PALN metastases, as compared to 0% with >4 PALN metastases.9 Similarly, Yamada et al. also found that 5-year recurrence-free survival was significantly better with fewer PALN metastases (p = .01).17

With regards to the extent of resection, Ogura et al. reported a higher 5- year cancer-specific survival in those who underwent R0 versus R1 resection of PALN (90.3% vs. 12.5%, p = .0003).10 Similarly, Nakai et al. also demonstrated a 5-year OS of 29.1% as compared to 10.4% (p = .017) in a comparison of outcomes following R0 and R1/R2 resection respectively.15

3.6 Role of chemoradiotherapy in PALN metastasis

Min et al. demonstrated that resection of metachronous para-aortic nodal metastasis had a survival benefit over chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy alone. They reported that the median OS in the PALND group was 34 months, which was significantly better than the 14 months in the non-resection group (p = .034).5 Johnson et al. (2018) also showed that preoperative chemoradiotherapy prior to lymphadenectomy on isolated PALN metastasis was associated with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 45%.1

3.7 Complications from PALND

PALND should also be weighed against the risk of complications. Rates of post-operative complications in patients undergoing PALND ranged from 7.8% to 33% (Table 3). There were no documented complications specific to PALND identified in this systematic review.

3.8 Criteria for PALND

Amongst patients who achieved R0 resection, the histological type and number of PALN metastasis were found to be a weighty prognostic factor.4 Several studies suggested that the presence of two or fewer PALN metastases and a pre-operative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level of <5 was associated with a better prognosis, indicating that two or fewer PALN metastases may be a good indication for PALND.2, 18, 19 Other studies also suggested that patients with PALN metastasis with other concurrent organ involvement may not benefit from PALND.2, 20

4 DISCUSSION

In this systematic review of PALN metastases in CRC, PALND was found to be associated with a survival benefit when compared to non-resection. Metachronous PALND was found to be associated with better OS as compared to synchronous PALND. The number of PALN metastases was noted to be a factor helpful when selecting patients for PALND.

In the management of CRC, the presence of lymph node metastasis is an important prognostic factor.5, 7 More precisely, the location and the lymph node metastasis and the number of involved nodes impact not only the choice of treatment but also the long-term survival of patients with these metastases.10 Modern-day imaging such as abdominal computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography can aid with the identification of lymph node metastases or recurrences. However, not all patients with suspicious findings on preoperative imaging studies have pathologically positive lymph nodes. Surgical resection is the only definitive way to pathologically confirm the presence of positive lymph nodes, and also contributes to better disease control than radiotherapy treatment alone.14

PALN metastases have generally been considered a systemic disease. As such, there has been limited research with regard to the utility of its resection in patients with CRC. In this systematic review, it was found that PALND was associated with significantly better survival outcomes in patients with CRC, as compared to patients who didn't undergo resection of PALN metastases.2, 5, 13, 14, 16, 18 PALND was also noted to be superior to chemoradiotherapy alone, although pre-operative chemoradiotherapy was associated with better survival.1, 5 Improved survival was also associated with the presence of fewer PALN metastases, and a low CEA level.

Metachronous PALN metastases occur in approximately 1% of cases, close to the primary site, and are a sign of underlying lymphatic spread.3, 5, 6, 9, 21 It has been proposed that synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastases have distinct underlying tumour biology given that patients with synchronous metastases generally have poorer survival outcomes. It has been hypothesised that metachronous metastases are associated with a reduction in molecular marker expression, which may lead to a post-translational degradation of the protein. The subsequently reduced rate of proliferation of liver metastases is thought to lead to improved survival outcomes when compared to synchronous metastases.22 Findings from Choi et al. and Arimoto et al. where metachronous PALND patients were found to have better OS as compared to patients with synchronous PALND patients may be a testament to the validity of this hypothesis.2, 6

In a recent systematic review of CRC patients with synchronous and metachronous PALN metastases who underwent lymphadenectomy, OS was noted to improve following PALND.16 Predictors of improved survival in patients with synchronous PALND included a well-differentiated histology, R0 resection, and the presence of less than two PALN metastases. In contrast, a longer disease-free interval was associated with improved OS and DFS in patients with metachronous metastases.16

Given the paucity of studies published on PALND, it is difficult to definitively recommend that it be performed in patients with PALN metastases, at least based on the currently available literature. However, findings from this systematic review suggest that disease control benefits from PALND coupled with multimodality treatments including chemotherapy or radiotherapy are comparable to those following treatment for isolated hepatic or pulmonary metastases. There is therefore a role for PALND to be considered within a multidisciplinary treatment framework for patients in the absence of clear guidelines advocating for its utility. Relative indications for PALND may include the presence of <3 PALN metastases, the presence of metachronous metastases, and a low CEA level, with the aim of performing an R0 resection.

After PALN resection, high rates of recurrence are to be expected, which is similar to that in patients who undergo chemoradiotherapy alone.16 Given that patients with PALN have a poor prognosis, it is therefore imperative to carefully select patients to undergo PALND given the inherent morbidity. Excessive lymph node dissection can result in serious morbidities including diarrhoea and sexual dysfunction. Common complications described after PALN surgery can include urinary dysfunction, ileus, wound, bleeding, and anastomotic leaks. It is reassuring to note that no PALND-specific complications were noted in this review.

The decision-making calculus should take into account the possible complications of PALND, and consider patient-specific factors on a case-by-case series to appropriately select patients for this procedure. In addition, the utility of resecting re-recurrence of PALN metastases in a manner similar to repeat liver resection for liver metastasis re-recurrence versus administering further adjuvant chemotherapy should be discussed. Only a single study which conducted resection of re-recurrence was included in this systematic review, and more research is needed on this topic.

This study has several limitations. All analysed data was retrospective in nature, and most studies had a small sample size with a likely underlying selection bias. It was difficult to directly demonstrate the impact of PALND on prognosis. This paper, at times, directly compared the survival outcomes between patients who did and did not undergo PALND, finding that survival improved with PALND. However, it would be prudent to acknowledge that this comparison may have been a false dichotomy, as the patients who did not undergo PALND were likely to have more aggressive tumours or be in poorer general condition, precluding them from a surgical option.

5 CONCLUSION

PALND in CRC has been noted to have some promising results in this systematic review of small-scale retrospective studies. A prospective multicentre international database is required with standardised definitions and surgical techniques to better appreciate the long-term oncological outcomes of PALND. For the present, PALND should be considered within a multidisciplinary approach for patients with CRC, in conjunction with already established treatment regimens.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

There are no sources of funding to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable as this is a systematic review.