Enhancing or impeding? The influence of digital systems on interprofessional practice and person-centred care in nutrition care systems across rehabilitation units

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Abstract

Aims

Digital health transformation may enhance or impede person-centred care and interprofessional practice, and thus the provision of high-quality rehabilitation and nutrition services. We aimed to understand how different elements and factors within existing digital nutrition and health systems in subacute rehabilitation units influence person-centred and/or interprofessional nutrition and mealtime care practices through the lens of complexity science.

Methods

Our ethnographic study was completed through an interpretivist paradigm. Data were collected from observation and interviews with patients, support persons and staff. Overall, 58 h of ethnographic field work led to observing 125 participants and interviewing 77 participants, totalling 165 unique participants. We used reflexive thematic analysis to analyse the data with consideration of complexity science.

Results

We developed four themes: (1) the interplay of local context and technology use in nutrition care systems; (2) digitalisation affects staff participation in nutrition and mealtime care; (3) embracing technology to support nutrition and food service flexibility; and (4) the (in)visibility of digitally enabled nutrition care systems.

Conclusions

While digital systems enhance the visibility and flexibility of nutrition care systems in some instances, they may also reduce the ability to customise nutrition and mealtime care and lead to siloing of nutrition-related activities. Our findings highlight that the introduction of digital systems alone may be insufficient to enable interprofessional practice and person-centred care within nutrition and mealtime care and thus should be accompanied by local processes and workflows to maximise digital potential.

1 INTRODUCTION

The impact of nutrition on patient outcomes in rehabilitation is well-established, including functional ability, quality of life and length of stay.1-3 Thus, optimising nutrition care systems (encompassing dietetics and food services, as well as mealtime care) within rehabilitation is necessary, especially given the increasing reliance on rehabilitation services globally.4 This may be facilitated by person-centred care,5-8 and interprofessional practice.9-12 Furthermore, dietetics and food services in inpatient settings such as rehabilitation are influenced by systems and care models,8, 13, 14 with elements of these increasingly becoming digitalised.15-18

Digital transformation in healthcare is here and brings with it the potential to enhance healthcare processes, outcomes and experience.19, 20 Both consumers (i.e., patients and support persons) and organisations may benefit from digitalising healthcare systems and processes, with improvements in the accessibility, safety and effectiveness of practice.21, 22 Research has highlighted the specific advantages of digital approaches to nutrition and food services across healthcare settings, such as supporting choice at point of meal service,23 improving monitoring processes for nutritional intake,24 enhancing patient participation in nutrition care,21 and improving the nutrition-related outcomes of patients.17 Evidence also suggests that digital systems (e.g., electronic medical records) may adversely impact person-centred care and interprofessional practice.15, 25, 26 However, this is yet to be explored specifically in nutrition care.

Making a change in healthcare, such as introducing a new technology, can be complex and disruptive.27-29 This is influenced by the healthcare system itself being a complex adaptive system.30, 31 Complex adaptive systems have fuzzy boundaries, contain agents that interact and adapt based on internalised rules and are embedded within other systems with which they may co-evolve.30 While introducing a new technology may be conceptualised as being a ‘simple’ intervention (e.g., a fixed intervention with one active component), the healthcare system itself remains ‘complex’ (e.g., has many interrelated components which may change and adapt over time).27 Thus, the process and outcome of introducing the new technology may be unpredictable and non-linear, given the system must evolve to accommodate this change.30 This understanding supports a move towards considering how systems in healthcare work and interact through the lens of complexity science, to better understand the nuances of making change within a complex adaptive system.31

Given the evolution of digital transformation in healthcare, including rehabilitation services, it is necessary to understand how digital systems influence practice within nutrition care systems. Therefore, we aimed to understand how different elements and factors within existing digital nutrition and health systems in rehabilitation units impact person-centred and interprofessional nutrition care practices through the lens of complexity science.

2 METHODS

We undertook an ethnographic study to explore how digital systems affect the person-centredness and interprofessional nature of nutrition care in rehabilitation.32 Ethnography is a multifaceted methodology with some suggesting that it is a toolbox of methods, including observation and interviews.33 We chose ethnography to support exploring and contextualising the practices, interactions, experiences, and culture of a specific group.33-35 Ethnography was recently used to understand the impact of digital transformation in rehabilitation.29 Our ethnographic field work included observation and interviews with patients, support persons and staff, supporting a holistic exploration of practice. Our research was completed through an interpretivist paradigm, embracing subjectivity in data collection and analysis.36, 37

We conducted this study on three subacute rehabilitation units—two of which were at the same site—all from one health service. We purposively selected these units as there were different food service systems, mealtime care arrangements and dietetic models of care across sites, as well as variations within how digital nutrition and health systems were used (see Table 1). This supported our exploration into the interactions between these different systems and the influence on nutrition and mealtime care. Similar staff were employed across sites including nutrition assistants, food service officers, nurses, doctors, and allied health staff. We gained support from the directors/managers of medicine, nursing and allied health before securing ethical approval from the health service (HREC/2021/QRBW/75477) and University of Queensland (2021/HE001190) ethics committees.

| Details | Site A | Site B |

|---|---|---|

| Included units (n) | 2 | 1 |

| Years of operation | 1 | 11 |

| Medical record | Digital: integrated, electronic medical record (Cerner) | Paper based |

| Dietetics referral system | Integrated, electronic medical record: (1) Automated digital referral to dietetics for patients at risk of malnutritiona and (2) manual input | Direct contact with or without manual input into Patient Flow Managerb |

| Diet code communication process | Diet code directly entered into Patient Flow Manager which feeds into CBORDc via an automatic digital interface | Diet code directly entered into CBORD with ad-hoc entry into Patient Flow Manager |

| Meal ordering | Digital: (1) order taken at point of meal service by nutrition assistant or food service officer, or (2) on the day of service via self-selection on the bedside patient engagement system or by nutrition assistantd | Paper-based: Completed via nutrition assistant providing a spoken menu system with orders taken 2 days in advance |

| Food charts | Digital: Recorded in CBORD by food service officer for every meal and snack consumed | Paper-based: Completed ad-hoc by nursing staff at the request of staff (e.g., dietitian) |

- a A score of ≥2 on the Malnutrition Screening Tool completed on admission by nursing staff triggers a referral to dietetics.

- b Patient Flow Manager is a digital handover system that can be used to capture and share information across the healthcare team, including diet code, mealtime needs and referrals.

- c CBORD (Roper Technologies) is the digital menu management system used across sites.

- d Nutrition Assistants take meal orders on the day of service, if needed, except for breakfast which is completed the day prior.

Patients, support persons, and staff on the study units were eligible to participate. For observations, an opt-out consent approach was approved. To notify potential participants of the study and to provide the opportunity to opt-out, flyers summarising the study and the primary researcher's details were displayed across sites, routinely offered to patients and support persons (by support staff who were not part of the research team), and shared electronically with staff. Patients and support persons could opt-out by notifying their nurse, and staff could notify a manager, if they did not wish to directly contact the primary researcher. For interviews, consent was verbal following a brief explanation of the study (for opportunistic interviews) or written (for scheduled interviews). Patients who lacked the capacity to provide consent for interviews were excluded; however, their de-identified data may have been captured in observations. The primary researcher purposively sampled staff to ensure diversity based on profession and role (i.e., allied health, nursing, medical professionals; clinicians, managers and support staff). Patients and support persons were identified in collaboration with staff, or via convenience sampling (e.g., those in the dining room at a given meal period). Snowballing was also used. Unique identifiers were ascribed to each participant to protect anonymity.

Fifty-eight hours of field work were completed between September 2021 and April 2022 involving 165 unique participants (see Table 2). Field work was completed by the primary researcher, a clinical dietitian with a strong interest in nutrition services and systems in rehabilitation. The primary researcher had previously worked across both study sites, and was working on one unit at the time of the study, therefore was known to some participants. To promote transparency, she wore different identification badges to distinguish her positions and confirmed her role as a researcher when speaking to potential participants. When seeking consent for interviews, the primary researcher reiterated that participation was voluntary and that not taking part in the study or withdrawing would not negatively impact patient care or care relationships.

| Participant group | Observations | Interviews | Field work overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 27 | 23 | 46 |

| Support Personsa | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Support Staffb | 48 | 18 | 51 |

| Healthcare Professionalsc | 47 | 31 | 62 |

| Total | 125 | 77 | 165 |

- a Support persons include family, carers, and friends.

- b Support staff include clinical (e.g., nutrition or nursing assistants), operational (e.g., food services and patient support services), and administrative support staff.

- c Healthcare professionals include staff from dietetics, speech pathology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work, psychology, nursing and medicine. One of the healthcare professionals observed and six who were interviewed held management positions with healthcare professional backgrounds.

Overall, 28 h of observations were completed involving 125 participants on different days of the week and at different times of the day to capture a range of participants and activities (see Table 3). Handwritten notes of observed practices were taken in the field, using a recognised framework focused on the nine dimensions of space, actor, activity, object, act, event, time, goal, and feeling.38 The primary researcher reconstructed these electronically soon after the observation episode. Reflexive notes were also taken using the same documentation and reconstruction process. The reflexive notes captured the primary researcher's interpretations of the data as well as any reflections on the data collection process (e.g., effectiveness of methods and areas for further exploration).

| Observed activities |

|---|

| • Meal ordering by a nutrition assistant or patients. |

| • Meal service (e.g., plating or delivery) for breakfast, lunch, dinner and snack periods. |

| • Dietetics service delivery (e.g., initial or review consultations) provided by a dietitian or a nutrition assistant. |

| • Team meetings such as |

| ○ Case conference with interprofessional team members |

| ○ Dietitian-nutrition assistant handover |

| • Clinical services provided by different staff such as |

| ○ Medical ward round |

| ○ Speech and swallowing therapy |

| ○ Occupational therapy-led meal preparation group |

Additionally, the primary researcher completed 30 h of interviews (opportunistic and scheduled) with 77 participants. Interviews were conversational in nature, with questions loosely following a pre-prepared interview guide (see Table 4). Opportunistic interviews were often ad-hoc and occurred face-to-face on-site, while scheduled interviews were held face-to-face in a private place or via Microsoft® Teams. Interviews were recorded (with consent reconfirmed verbally) and transcribed using Microsoft® Word 365 Online. The primary researcher verified recordings by listening back, checking transcripts for accuracy and adding background or contextual information or non-verbal cues from field notes or reflexive notes.

| Interview questions |

|---|

• Can you tell me about how the mealtime model of care in this unit was planned? Prompt: Were consumers involved? |

• Can you tell me about protected or communal mealtimes on the unit? Prompts: What does this mean? Who's driving it? |

| • What are the strengths and limitations of current dietetic or food service workflows or models in supporting person-centred nutrition care? |

• What are the strengths and limitations of current nutrition and mealtime care practices and handover processes in supporting interprofessional practice in nutrition or mealtime care? Prompts: How is this done? What systems are used? |

| • What would make it easier for you to provide person-centred nutrition care? |

| • What would make it easier for interprofessional involvement in nutrition or mealtime care? |

• Can you tell me about how you order your meals? Prompts: How do you find that process? What's easy/hard about it? Has anyone helped you with this? |

We used reflexive thematic analysis to guide data analysis.39, 40 This method aligned with our interpretivist approach, embracing researcher subjectivity in creating knowledge from the data as relevant to our research aims.41 Furthermore, the theoretical flexibility of reflexive thematic analysis supported the consideration of complexity science to inform our interpretations.39 We applied the six phases of thematic analysis—familiarisation; coding; initial theme generation; theme review; theme naming, refinement, and definition; and writing the report40—recursively, considering inductive and deductive orientations to the data. We considered elements of complexity science such as overlapping networks, non-linearity, adaptation, and emergence when developing our initial themes.30, 39 A sample of the transcripts and field notes were independently coded by a senior member of the research team (AMY) and discussed to consider alternate viewpoints.

We utilised various strategies to promote rigour in our study. First, we ensured internal coherence by aligning the philosophical positioning, methodology and methods of this study.36, 42 Second, we showed commitment to enriching the depth and breadth of the data collected, thus the credibility of our findings, by the primary researcher's prolonged engagement in the field of inquiry, and by using different data collection. Third, we valued researcher reflexivity and considered alternative orientations to the data, documenting reflexive notes during field work and routinely discussing these with the research team. Regular discussion with the research team also occurred during the analysis process, supporting coding and theme development. Last, we considered the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist,43 alongside a tool for evaluating thematic analyses,44 to guide the comprehensive reporting of this study.

3 RESULTS

We developed four themes to understand the influence of digital systems on the person-centredness and interprofessional nature of nutrition and mealtime care in rehabilitation: (1) The interplay of local context and technology use in nutrition care systems; (2) Digitalisation affects staff participation in nutrition and mealtime care; (3) Embracing technology to support nutrition and food service flexibility; and (4) The (in)visibility of digitally enabled nutrition care systems.

The first theme, ‘the interplay of local context and technology use in nutrition care systems,’ described how contextual factors across each site affected which digital systems were used in dietetic and food service workflows.

The sites’ length of operation seemed to influence the use of technology. Site A was a newly established digitally enabled facility where the dietetics team embraced technology in their services. For example, there was a systematic, delegated model of care supporting timely intervention for patients at risk of malnutrition, where nutrition assistants would re-screen automatic digital referrals to dietetics, initiating nutrition interventions as required. However, some dietetics staff highlighted that the technology-enabled, protocolised model of care may exacerbate the imbalance between task-orientated and person-centred care. They suggested that this model may increase the tendency for nutrition care plans to be informed by the protocol and screening tool result, rather than the person.

Conversely, Site B was a long-standing service using less technology, despite dietetics staff also being eager to embrace digitalisation. Efforts had been made to use a digital handover system to streamline and enhance the continuity of referrals across dietitians and the wider team; however, dietitians reported inconsistent adoption by interprofessional team members. This may reflect the challenge of changing ingrained practice workflows.

The local change culture also appeared to influence the proclivity of staff to translate digital innovations into practice. Dietetics and nursing staff from Site B offered suggestions of how digital systems could be better harnessed in the nutrition care system. Despite their eagerness for change and improvement, altering elements of long-standing nutrition and food service systems was reported as difficult by some. Reasons for this suggested by staff included the anticipated resistance of some staff, inadequate staffing, budget constraints, extensive stakeholder engagement required for change, and complex governance structures. The impact of these barriers was reflected in the absence of change noted by staff.

“[Reflecting on changes regarding nutrition and mealtime care over time]: Umm, I can't say [I've seen] too many changes. I know that there was the implementation of the project with the [mid-meals] in the gym… But otherwise I don't think there's been any significant changes.” –Healthcare Professional 1, Site B.

On the contrary, dietetics staff at Site A felt that making change was easy and welcomed due to the site being young and digitally enabled. The technology embedded within the dietetic and food service systems reportedly made these systems nimble to change.

“…[Site A] is… open to change… Very fluid… because it's based on a really efficient digital system. So like we've seen with the trial [of on-demand snacks via the bedside Patient Engagement System] here … and the way in which we're able to, switch from pre-ordering [snacks] or back to [ordering on-demand] … [You] don't have that fluidity at [other sites], because [the system is] based on a very regimented, paper-heavy, operational … structure.” –Support Staff 7, Site A.

The second theme, ‘digitalisation affects staff participation in nutrition and mealtime care,’ explored how digital systems influenced the roles and actions of staff across professions in nutrition and mealtime care. Activities related to the capture and handover of patient information (including meal preferences or needs) were impacted by digital systems. This information was considered essential in person-centred care, with staff from dietetics, food services, speech pathology and occupational therapy across sites involved to varying degrees.

Nutrition assistants and food service officers valued having information on-hand regarding patients’ meal preferences and needs to inform person-centred nutrition care. Once collected (primarily by nutrition assistants), this information was recorded in digital systems across sites, supporting continuity of care. These details were then used to inform care via hybrid digital and paper-based approaches, such as printing handover sheets and tray tickets with prompts or having a laptop or iPad with access to the menu management systems. Despite having information regarding the needs and preferences of patients in advance, the digital handover system was not seen to replace patient or support-person collaboration to complete menus or support self-selection, as needed (i.e., when independent self-selection was not possible). Thus, collaboration with patients or support persons remained an important element of person-centred care for staff assisting with menu selection, regardless of technology.

Dietetics and nursing staff at Site B identified increased utilisation of existing digital handover systems would help to improve person-centred care through the efficient entry and handover of meal-related information.

“I don't think we do well with handover. We've got it [handover capability] there in the Patient Flow [Manager], but we're not using it to the max. … our handover sheet is extracted out from Patient Flow Manager, so exactly what you're putting in, is what you're getting out … you know if they are on modified [cutlery] … We should be able to then go straight from the handover sheet—even if you had a casual staff—be able to read and go provide that assistance. So the tool is there, but it's just the utilisation of the tool.” –Healthcare Professional 21, Site B.

This digital handover system was poorly utilised, which from staff reports was due to a lack of awareness of the functionality available and how to use it, as well as a lack of clarity regarding whose responsibility it was to enter this information outside of dietetics and speech pathology. The digital handover system and related workflow in Site A facilitated the capture and sharing of information with greater ease in some cases, such as in the identification and handover of mealtime needs (e.g., assistance and aids required), which was a core responsibility of nutrition assistants. However, nutrition assistants desired further information from the interprofessional team regarding patients’ mealtime goals to better support person-centred nutrition care, with untapped potential for this to also be captured in existing digital handover systems.

The non-existent interface between some digital systems posed challenges for continuity of care and thus the provision of safe, person-centred nutrition care across sites. Workarounds had been created to circumnavigate these issues and ensure essential information was handed over (e.g., diet codes or allergies), such as the double entry of the same information into different digital systems. Some staff at Site B implied the lack of communication between digital systems reduced their motivation to encourage others to use these systems for interprofessional handover.

“… none of the systems talk. Even if nursing were to change a diet in [the digital handover system], that doesn't then talk to CBORD [digital menu management system]. … that would be an issue in regard to mealtime changes. So things like putting in preferences if [nurses] write a note in the diet comment box in [the digital handover systems], that does nothing.” –Healthcare Professional 3, Site B.

The digital menu management system was seen to enhance workforce capacity and enable interprofessional practice between food service and dietetic staff, in some cases. At Site A, food service officers recorded the intake of all hospital food and beverages directly into the menu management system. Dietetics staff valued this information, and nutrition assistants were reported and seen to use this real-time data to work to their full professional capacity by providing timely nutrition intervention within a delegated malnutrition model of care. Thus, using digital systems in this way was thought to facilitate a high-value model of care, enabled by the opportunity to create a new service.

The third theme, ‘embracing technology to support nutrition and food service flexibility,’ detailed that while many managerial, clinical and support staff commented on the intended benefits of digital systems on service flexibility, some clinical staff called attention to the unintended and undesirable consequences.

Digitally supported meal selection promoted greater flexibility compared to a paper-based system. For example, the digital menu management system at Site A allowed patients to choose their meals at the point of service, or order via a self-selection system. In contrast, selections were taken in 2 days in advance in Site B to allow time for this data to be entered manually into a digital system, processed and actioned. Clinical and managerial staff at Site B wanted to update their system to facilitate choice closer to the point of service. However, they alluded to barriers including the sheer scale of the change process that would be required and the anticipated resistance of some staff.

The digitally supported, flexible meal ordering system at Site A was seen to promote elements of person-centred nutrition care, such as autonomy, within the meal selection process. Patients had the option to complete same-day ordering of their lunch and dinner via a self-selection system enabled by the bedside Patient Engagement System. The ability to order snacks, in the same way, was introduced during field work, with the aim of allowing patients to better fit their snacks in between therapy sessions. Furthermore, this digital system provided an opportunity for interprofessional practice in nutrition care.

“…sometimes within a [therapy] session, we might use the [bedside Patient Engagement System], orientate them to the [the system] and ask them what they would like to order for lunch … referring to the pictures and then just encouraging that independence.” –Healthcare Professional 5, Site A.

It was also noted that the digital system supporting self-selection of meals had unintended and undesirable consequences on patient care. For example, staff from Site A admitted that self-selection was hard for some patients, including those who were not technologically savvy, or those with vision or upper limb impairments. However, workarounds had been established where nutrition assistants or food service officers (depending on the meal period and patient needs) would support self-selection. Further, the task of orientating and educating newly admitted patients on using this system was embedded in the nutrition assistant workflows. Although, one healthcare professional identified the inadvertent rigidity from the quality control in digital menu management systems as a barrier to person-centred care. This made it more difficult to facilitate safe, patient-led ‘blending’ of diet codes, compared to using paper-dominant systems.

“You kind of can't take so much of a hybrid approach [in the digital menu management system] unless it's something that you're physically providing the patient … like we have patients where we do sensory enhanced fluids for therapy, and they get to a point where we're like, you know what, morning tea and afternoon tea, you'll be okay [to have sensory enhanced fluids], it's a small volume. You'll be supervised. … and the nurses aren't able to provide that, because in the system they're still on thickened fluids …” –Healthcare Professional 13, Site A.

The final theme, ‘the (in)visibility of digitally enabled nutrition care systems,’ described how digital systems enhanced the visibility of the nutrition care system in some instances, while in others the reverse was evident.

Digital systems were found to enhance the visibility of elements of nutrition care for patients and support persons, which impacted person-centred nutrition care. At Site A, the entire day's menu (tailored to the patient's dietary needs, such as allergies) was visible via the bedside Patient Engagement System. The menu for each lunch and dinner meal service was also displayed in the dining room via a widescreen television. Staff and patients described how the enhanced visibility of menu items meant that patients could and were ordering more via the self-selection system compared to ‘traditional’ ordering processes (e.g., spoken menu by a nutrition assistant).

Using different digital systems across sites also influenced elements of interprofessional practice through data visibility and availability. Staff at Site B reported printing diet code information from the digital handover system, with allied health assistants providing this information to therapists each morning so that they could safely offer patients beverages during physical therapy sessions. However, the accuracy of this information may have been questionable as there appeared to be no consistent process of updating this for patients not under the care of a dietitian or speech pathologist. Gaining similar information at Site A was also seen and reported by staff from occupational therapy and physiotherapy to be challenging.

“[It's harder to offer a patient a drink during therapy] because we don't really have access to [the digital handover system] here, or not as easily.” –Healthcare Professional 14, Site A.

While staff at Site A admitted knowing how to gain this information (e.g., contacting the speech pathologist, or searching the electronic medical record for the last recorded diet code), there was an observed hesitancy to do this. This indicated that staff preferred to quickly access this information themselves rather than pursuing other means of handover.

Additional workarounds to combat the invisibility of some digital systems were identified, with a double-up of activity noted across two different digital systems at Site A. As previously mentioned, food service officers recorded hospital food and beverage intake for all patients in the digital menu management system, which improved the visibility and availability of this information to nutrition assistants and dietitians. However, nursing leaders and medical staff commented that nurses continued to complete food charts in the separate digital medical record at times, unnecessarily duplicating this task. At this site, only dietitians and nutrition assistants had access to the intake tracking reports in the digital menu management system.

“…we [healthcare professionals/managers] had big discussions about the usefulness of food charts. … if a patient was on a food chart, they should be referred to the dietitian anyway. None of us could think of any instance that you would need a patient on a food chart that the dietitian wasn't involved in. So they [the wider team] will always have access to that information [via the dietitian].” –Healthcare Professional 11, Site A.

Thus, limited access to nutritional intake information in the digital menu management system meant that doctors could not review this information proactively, leading to this task being duplicated.

4 DISCUSSION

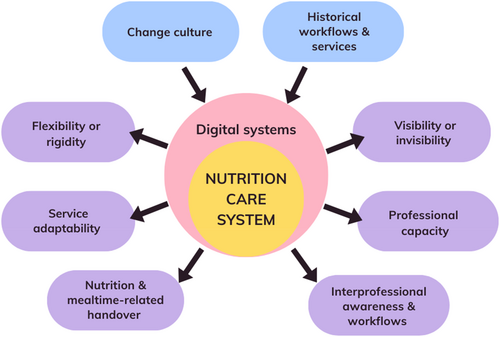

Through this ethnographic study, we aimed to understand how different elements of digital nutrition and health systems in rehabilitation units impact person-centred care and interprofessional practice in nutrition and mealtime care. Our findings highlight how digital systems used within the nutrition care system both enhance (e.g., increase agility, flexibility, visibility and professional capability) and impede (e.g., greater rigidity, hiddenness and disintegration) person-centred care and interprofessional practice. Overall, this study offers insights into how digital systems are used across nutrition care systems, which may be useful for managers and staff looking to embrace the digital transformation of healthcare. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of our findings.

We identified contextual challenges that impact digital transformation in nutrition care systems, including altering long-standing workflows and change culture. Others have reported similar findings when moving towards technology-supported models of nutrition care, along with challenges associated with upskilling and training an existing workforce in new technologies.45 Thus, organisations looking to improve existing digital systems, or move towards digitally enabled nutrition care systems may benefit from applying implementation science theories, models and frameworks,46 such as the Non-Adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread and Sustainability framework,27 to understand the barriers, enablers and opportunities for implementing digital innovation locally.

We found that digital systems—particularly menu management systems—can positively enable person-centred nutrition care. For example, flexible, digital systems that support the self-selection of meals and point-of-service ordering can promote patient autonomy. We have previously identified that autonomy is recognised as an important feature of person-centred nutrition care systems,47 with other research showing that patients value electronic meal ordering for its flexibility and convenience.48 However, we also noted unintended and negative consequences for person-centred care, exacerbated by the quality control embedded in digital systems. For example, the diminished ability for patient-led blending of diet codes when clinically appropriate and aligned with their goals. Tailoring digital systems to the needs of local teams and services may resolve this issue.49

Digital systems also positively and negatively influence interprofessional practice in nutrition care activities, with others, too, identifying mixed results in hospital settings (e.g., for electronic health records).15 In general, we found that digital systems enhance the visibility of nutrition information for patients, support persons and dietetics staff, while the opposite was true for occupational therapists, physiotherapists and doctors, and thus may exacerbate the isolation of nutrition care activities. Furthermore, we observed that embracing digital systems enhanced the ability of support staff (food service officers and nutrition assistants) to work to their full professional capacity within a systematic, delegated malnutrition model of care, with this possibility as suggested by others.45 Similar to previous research50 we also saw that a digital menu management system reduced the contribution of support staff in meal ordering with patients. However, this appeared to free up time for food service officers to be involved in other activities, such as providing mealtime care in a communal dining room model (where food service officers still took some meal orders with patients) and completing nutritional intake tracking.

Our study highlights that introducing a digital system alone may be insufficient to facilitate interprofessional practice in nutrition care. Similarly, Robertson et al. implied that face-to-face interaction between clinicians remains essential to support interprofessional practice when using an electronic health record.15 Thus, this suggests that interprofessional processes (e.g., workflows) should be collaboratively created, tailored to local contexts, then trialled, adapted and embedded to maximise the interprofessional practice potential offered by digital systems. Further, regardless of the handover system used (digital or not), our findings suggest that interprofessional workflows surrounding mealtime care may help to support person-centred nutrition care.

We also found that the non-existent interface between digital systems was a barrier to interprofessional practice, with similar inefficiencies highlighted previously.45 Thus, organisations should focus on ensuring that digital nutrition-related handover systems can effectively speak to other relevant systems. This may enhance the efficient, safe and team-wide distribution of valuable nutrition information and reduce the need for unproductive and time-wasting double-ups of data entry. Better information sharing across digital systems may also help patients to be more involved in their own care (e.g., nutrition-related self-monitoring,48 or using health information technologies in interactive learning51), which we have previously identified as important in person-centred nutrition care.47

There were strengths and limitations to our study. The primary researcher's background as a clinical dietitian supported prior understanding of different digital nutrition and healthcare systems. Sampling two sites with different dietetics and food service systems, lengths of operation, and digital system usage strengthened our in-depth investigation of digital systems across different care models, and thus the transferability of our findings. Transparent reporting of the digital systems used may also support transferability to other healthcare settings with similar staffing structures, and nutrition and food services. However, the limitations are that observations were not completed within kitchens, nor were staff in information technology roles interviewed, which may have offered additional insights into the impact of digital systems.

This is the first study to explore the influence of digital systems on person-centred care and interprofessional practice specifically in nutrition and mealtime care. Our findings highlight key considerations for health services looking to implement digital systems, or optimise person-centred care and interprofessional practice within existing digitally enabled nutrition care systems. Future research should focus on optimising the functionality and use of different digital systems in nutrition care systems, involving patients, support persons and staff as end-users in this process.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the design of this study. HTO led the completion of data collection and analysis. AMY also provided input into formal analysis, with EO, AMY and TLG all providing supervision and support during the entire analysis process. HTO completed the initial draft of the manuscript, with all authors providing input into further writing, review and editing. All authors have critically reviewed the content of this manuscript and approved the definitive version submitted for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Adrienne Young is an Associate Editor of Nutrition & Dietetics. They were excluded from the peer review process and all decision-making within the journal editorial team regarding this article. This manuscript has been managed throughout the review process by the Journal's Editor-in-Chief. The Journal operates a blinded peer review process and the peer reviewers for this manuscript were unaware of the authors of the manuscript. This process prevents authors who also hold an editorial role to influence the editorial decisions made. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship awarded to the doctoral researcher, Hannah Olufson.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.