Understanding the Perspectives of School Children Who Stutter: A Rapid Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Children who stutter have the right to express their views and be heard. However, in research on stuttering, attention tends to focus mainly on parental and adult perspectives. By actively engaging with children's viewpoints, we can enhance our understanding of their distinct needs and capabilities. This, in turn, enables the development of more personalised and child-centred interventions based on their lived experiences.

Aim

This rapid review aimed to identify qualitative methods in the research literature employed to explore the perspectives of school children who stutter (SCWS) aged 6–12 years and identify topics discussed by the children in such research.

Methods and Procedures

A rapid literature review was conducted using five databases: EBSCO CINAHL, Scopus, EBSCO PsycINFO, Embase, and OVID Medline. The search strategy focused on qualitative or mixed-method peer-reviewed studies and included a manual search of the reference lists of identified papers. The search targeted studies involving school-age children who stutter and excluded grey literature. The findings are presented through data extraction tables and a narrative summary.

Outcomes and Results

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria, all of which used at least one qualitative method to elicit the children's voices. A total of 14 methods across the 13 studies were identified. The most common method was open-ended questions as part of semi-structured interviews. In relation to what SCWS expressed about their talking, several insights emerged, including reports of wishing to participate in group discussions in school and fluency changes post-intervention. The findings revealed the multifaceted nature of the experiences of SCWS, from personal frustrations to positive transformations.

Conclusions and Implications

This rapid review provides a comprehensive overview of current qualitative approaches to understanding the perspectives of SCWS. It highlights the need to include the voices of SCWS in research. It advocates for innovative, authentic approaches to data collection and emphasizes the necessity for further research to bridge gaps in understanding the experiences and perspectives of children who stutter.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

- Stuttering goes beyond the act of stuttering and the impact on SCWS is influenced by a range of factors. Listening to the perspectives of SCWS is important to understand their individual needs, which will help facilitate more child-centred practice. It is important to consider that the method of eliciting children's perspectives may affect the results.

- This review identifies current methods used to listen to SCWS and identifies gaps in the research in relation to studies that focus exclusively on exploring the perspectives of SCWS on their talking. Furthermore, it identifies a range of issues that SCWS report as important in their lives.

- The review emphasises the necessity of researchers and clinicians employing multimethod approaches to listen to SCWS. It also underscores the importance of collaborating with SCWS themselves in addition to working with parents as proxies to ensure person-centred care. Refining these methods to actively include the perspectives of SCWS in decision-making leads to significant potential promote the agency of SCWS in both research and clinical contexts in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations 1989).

1 Introduction

Stuttering is a neurodevelopmental disorder influenced by motor, linguistic and emotional factors (Smith and Weber 2017). When considering the viewpoint of school children who stutter (SCWS), the phenomenon of stuttering encompasses a wide range of aspects beyond the act of stuttering (Tichenor and Yaruss 2018, 2019; Yaruss and Quesal 2004). Many researchers have reported that stuttering often affects the quality of life for those who stutter, leading to negative emotions such as anxiety in SCWS, who may be at risk of isolation and bullying, ultimately resulting in communication problems, affecting the child's academic success and school participation (Blood and Blood 2004; de Sonneville-Koedoot et al. 2014; Erickson and Block 2013; Karahan Tığrak et al. 2021; Langevin et al. 2009; Yaruss 2010). Therefore, it is essential to listen to the experiences and perspectives of SCWS to gain a holistic picture of the child for appropriate intervention and support (Bölte 2023; Tichenor, Constantino et al. 2022; Tichenor, Herring et al. 2022; Tichenor and Yaruss 2019).

The significance of Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (United Nations 1989) recognition of the fundamental entitlement of children to express their opinions freely and have those opinions duly considered in issues that concern them. It is important that all children have the opportunity to express their opinions, engage in decision-making processes that impact their lives, and acknowledge their growing ability to participate in such processes (Thomas 2007). It is important that we identify the methods being used in research to listen to the perspectives of SCWS.

In research and clinical practice, parental and adult input is frequently relied upon to understand children's views (Gallagher et al. 2019; Goldbart and Marshall 2011; Markham and Dean 2006; Markham et al. 2009; Roulstone and McLeod 2011; Salvo and Seery 2021). This reliance places greater emphasis on parents’ and adults’ views of the child's speech and communication needs rather than seeking the child's views (Tisdall 2018). Parents’ and adults’ perceived impact of the child's needs are valuable (Rocha et al. 2020). However, combining them with the child's perspective offers a more holistic view (Campbell 2000; Korelitz and Garber 2016). Rocha et al. (2020) found that SCWS (7–12 years) viewed the impact of their stuttering as less significant than their parents did. The results also highlight that both parents and their children have unique needs, emotions, views and concerns related to stuttering. Furthermore, Vanryckeghem (1995) reported that parents of SCWS are often unreliable representatives of their children's communication attitudes. Listening to children's perspectives and experiences allows us to gain insight into their unique lived experiences and can add to the development of interventions that foster their participation and well-being (Bedoin and Scelles 2015; Brundage et al. 2021; Carroll and Twomey 2021; Dockett and Perry 2007; Merrick et al. 2019; Tichenor, Herring et al. 2022).

Many researchers have reported that stuttering impacts SCWS's quality of life (Blood and Blood 2004; de Sonneville-Koedoot et al. 2014; Erickson and Block 2013). For instance, SCWS's are at risk of being isolated and bullied, which leads to negative emotions such as anxiety. As a result, the children's communication problems aggravate it. Therefore, the speech and language therapist (SLT) requires a range of assessment tools to get a holistic picture of the child, including the aetiology, the characteristics of stuttering, and the overall effect on the child's life (Tichenor and Yaruss 2019). Following the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework.

Children and adolescents with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) demonstrate their ability and willingness to engage in discussions regarding their needs and desires (Lyons et al. 2022). There are frameworks that can help researchers to improve children's participation in research, such as Lundy (2007) and Hart (1992). Lundy's (2007) model emphasises the importance of space, voice, audience and influence in creating opportunities for children to express their views and have them heard and taken seriously. Hart's (1992) Ladder of Participation involves levels of people's participation in decision-making processes ranging from non-participation to full partnership. Implementing Lundy's (2007) model involves creating a safe and inclusive space for children with SLCN to express themselves, using a variety of communication methods to support their expression (e.g., speech, gesture, drawing, writing, pictures, photographs, art and technology) ensuring that diverse voices are included (Gillett-Swan and Sargeant 2019; Hanna 2022; Lyons et al. 2022; McAllister et al. 2022). It also involves allowing time for children to think deeply about topics, providing ongoing and open opportunities for expression, and listening to and acting on children's views (Tisdall 2015).

When seeking to understand a person's experiences comprehensively, it becomes imperative to explore their subjective perspective (Rahman 2020). In this regard, the exploration of a child's thoughts and experiences through qualitative methods such as interviews, questionnaires and open-ended conversations is essential (Rambod 2018). Qualitative research involving children and young individuals with SLCN can serve as a valuable complement to quantitative research (Lyons et al. 2022). By adopting these qualitative approaches, researchers, clinicians and educators can effectively gain a nuanced understanding of dynamics pertaining to children and the concept of childhood (Rahman 2020).

The current study systematically summarised qualitative research relating to methods employed in gathering the perspectives of 6–12 years old SCWS. The research question addressed was: What are the qualitative research methods used to gather the perspectives of school-age children who stutter?

-

To summarise the research on exploring the perspectives of SCWS.

-

To identify the specific purposes of each data collection method in facilitating and capturing children's perspectives.

-

To identify the perspectives of the children about their talking.

2 Method

A rapid review (RR) offers an overview of the literature, emphasises important contributions, identifies areas that need further investigation, and expedites the production of significant scientific findings, thereby guiding practical applications and future research (Law et al. 2021). RRs produce evidence in a timely and resource-efficient way and help highlight areas that need further research, thereby guiding future research priorities (Garritty et al. 2025; Towers et al. 2020). Furthermore, this RR has supported our ongoing primary research study design (Garritty et al. 2025; McLennan et al. 2021) which focused on understanding the lived experiences of SCWS in a holistic way. This review followed the Cochrane Rapid Reviews guidelines (Garritty et al. 2021) outlined below and was conducted between January and June 2023. The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022383537). Rapid reviews have been criticised in relation to rigour (Ganann et al. 2010). The authors employed strategies such as multiple reviewers to attend to rigour and these are described in more below. To frame the search strategy, we employed the SPIDER framework (Cooke et al. 2012), which is presented in Table 1.

|

School children who stutter (ages 6–12). |

|

Methods used to gather the perspectives of SCWS. |

|

Qualitative methods used (e.g., drawing, photo elicitation, interviews) in peer-reviewed journal articles. |

|

How these methods gathered children's perspectives. The topics children talked about. |

|

Qualitative/Qualitative component of mixed methods. |

2.1 Search Parameters and Database Searches

- • Qualitative research or mixed methods articles with a qualitative component.

- • Articles in English only.

- • Peer-reviewed publications.

- • Available electronically.

The decision to focus on the school-age group was grounded in recognising the potentially heightened emotional and quality-of-life impact of stuttering on children between the ages of 6 and 12 years (Guitar 2014). By concentrating on this age cohort, the review aimed to provide a more nuanced understanding of the methods and approaches utilised in studying the perspectives of school children.

We identified keywords based on the research question, which involved four main concepts: (1) children, (2) stuttering, (3) perspective and (4) method. Each concept was organized with its synonyms (see Table 2). Before initiating the search, the three authors reached a consensus on these keywords and consulted with an experienced librarian.

| Sample | Child* OR paediatric* OR paediatric* OR pupil* OR ‘School-age’ OR ‘Service user’ AND Fluenc* OR Fluencies OR Stutter* OR Stammer* OR ‘Speech impairment’ OR Dysfluency OR Disfluency OR ‘Childhood stuttering’ OR ‘Developmental stuttering’ |

| Phenomenon of Interest and design | Draw* OR Sketch*OR Illustration* OR Outline* OR Art* OR Interview* OR ‘Arts based’ OR Photo* OR Pictur* OR Question* OR Questionnaire OR Ethnograph* OR Narrative OR Delphi |

| Evaluation | Idea OR Ideas OR Perspective* OR Feel* OR Experience* OR View* OR Listen* OR Hear OR Hearing OR understand* OR Voice* OR Facilitat* OR Consult* OR Engage* OR Emotion* OR Perception |

2.2 Conducting the Search

The first author searched five databases, EBSCO CINAHL, Scopus, EBSCO PsycINFO, Embase and OVID Medline, following consultation with the second and third authors and an experienced librarian. The references and bibliographies of the included studies were checked for additional citations. Electronic alerts for key journals were set up to identify newly published work. Database filters were applied to include only English-language and peer-reviewed journal articles involving SCWS.

2.3 Selecting Studies

Selecting the studies involved two phases. Search outputs were checked for duplication using the reference management tools Endnote Desktop 20 (2023) and Rayyan (Ouzzani et al. 2016). Furthermore, Rayyan (Ouzzani et al. 2016) facilitated screening by the three authors and made similarities and variations in decision-making during the two screening phases transparent. In Phase 1, the first author screened titles and abstracts based on the predetermined inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for this review were as follows: articles must include SCWS between the ages of 6 and 12 years, be published in English-language, and be peer-reviewed publications available electronically only. Grey literature was excluded from our study due to time constraints. The second and third authors conducted blind title and abstract screening of a random selection of 20% of the papers. During this phase, articles failing to meet the criteria were excluded. If the reviewers were uncertain, the studies were included in a full-text review.

In Phase 2, the first author conducted a full-text screen. The second and third authors independently assessed 100% of the articles to ensure fit with the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, the first author screened the reference lists of the included papers. The second and third authors independently assessed 100% of the screened reference lists. There was 100% agreement between the reviewers in relation to the final selection of articles. If discrepancies had arisen, the researchers would have engaged in detailed discussions to reach an agreement by consciences. This approach would have ensured that all included studies adhered to the predefined eligibility criteria and reduced potential biases (Lefebvre et al. 2019).

2.4 Extracting Data

Two data extraction forms were created. Table 3 presents an overview of the studies and includes details about study design, sample size, participant age ranges, geographical location and methods used to elicit voice. Table 4 highlights relevant characteristics of the methods identified in the studies.

| Authors | Location/Setting | Study purpose | Study design | Participant information | Qualitative methods used to elicit the voice | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics Number/Age /Gender |

First language | ||||||

| 1 | Lau et al. (2012) | Australia/Clinical setting | Examine if SCWS and fluent peers differed in care and control parenting strategies, parent-peer relationships, and self- and parent-reported child social behaviour. Also, to understand SCWS child perspectives, attitudes and social connections to peers and parents. | Mixed method | 10 participants, range: 8–14 years (9 males and 1 female) | English | Individual semi-structured interviews |

| 2 | Iimura et al. (2021) | Japan/Special education classes | Examined requests from school-age and adolescent stutterers towards the people around them. | Mixed method | 64 participants, of which 43 were school-age, range: 6–12 years (31 males and 12 females) | Japanese | Questionnaire with open and closed questions |

| 3 | Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017) | United Kingdom/Clinical setting | Examined SCWS's perceptions of the changes they made after intensive group therapy for stuttering, their most significant change, and the mechanism of change in relation to the therapy model's key components. | Mixed method | 5 participants, of which 3 school-age, range: 10.4–14.11 years (4 males, 3 females) | English | Individual semi-structured interviews |

| 4 | Fourlas et al. (2022) | Greece/Clinical setting | Introduces Lexipontix through a case study and explores its foundational principles and the effectiveness of the Lexipontix program. | Mixed method | 1 participant, 10-year-old male | Greek |

Structured interview using SFBT questions with parents and child Structured interview with child Emotion-graph completed by parents and child Structured interview with child using Alliance Interview Protocol |

| 5 | Gerlach et al. (2019) | United States/In convention | Investigated whether a multiday convention organised by stuttering support organisations affects cognitive and emotional changes in young stutterers. | Mixed method | 22 participants, range: 10–18 years (5 females and 17 males) (7 of 22 completed the interview) | English | Individual semi structured online interviews |

| 6 | Moïse-Richard et al. (2021) | Canada/Not available | Assessed the value of virtual classrooms in clinical practice with stuttering children and adolescents. | Mixed method | 10 of which 9 SCWS, range: 9–17 (2 females and 8 males) | French | Feedback about the participants’ experiences |

| 7 | Carey et al. (2014) | Australia/Telehealth | Evaluated a Webcam-based Phase II Camperdown Programme outcome with stuttering adolescents. | Mixed method | 16 adolescence males of which 1 SCWS, range: 12–16 years with one 12 years old SCWS | English | Post-treatment semi-structured interviews for adolescents |

| 8 | Prince et al. (2022) | United Kingdom/Clinical—residential setting | Conducted a feasibility study of the Fluency Trust Residential Course. | Mixed method | 12 adolescence of which 1 SCWS, range: 12:6–17:1 years (3 females and 9 males) | English | Semi-structured interview |

| 9 | Rodgers et al. (2020) | United Kingdom/Not available | Examined the viewpoints of children who stutter and their parents on the changes after 1 year of therapy. | Mixed method | 7 adolescences of which 2 SCWS, range: 11;9–14;3 years (5 males, and 2 females) | English | Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) worksheets adapted from De Shazer (1985) by Rodgers et al. (2020) |

| 10 | Berquez et al. (2011) | United Kingdom/Not available | Determined what information children, parents and education staff consider crucial for supporting a child who stutters in an educational setting, with the aim of developing suitable resources. | Mixed method | 25 SCWS/range: 7–11 and 27 young people who stutter age 12–18 years | English | Delphi method: Stages 2 and 3 (Goodman 1987) |

| 11 | Cooke and Millard (2018) | United Kingdom/Telehealth | Identified which outcomes are most important to SCWS. | Mixed method | 25 participants, range: 8;0–14;11 years (19 males and 6 females) | English | Delphi method: Stages 2 and 3 (Goodman 1987) |

| 12 | Turnbull (2006) | United Kingdom/Educational setting | This article includes a case study to demonstrate the advantages of an intervention approach for a child who stutter. | Qualitative | 1 participant, 10 years old girl who stutter | English | Semi-structured interview |

| 13 | Berquez et al. (2015) | United Kingdom/Clinical setting | Investigated the expectations of children who stutter and their parents regarding therapy, and determined if their hopes were in alignment. | Qualitative | 7 participants, range: 10–14 years (5 males and 2 females) | English | Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) scaling (De Shazer 1985) |

| Methods | Number of methods (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Techniques to elicit voice | Open ended questions | 13 |

| Draw emotional graph | 1 | |

| The mode of response | Verbal | 8 |

| Nonverbal | 1 | |

| Written | 4 | |

| Not specified | 1 |

2.5 Data Analysis

A narrative summary of the data was conducted (Boland et al. 2017). It involved categorising the methods based on what they aimed to measure and identifying differences and similarities across methods. Additionally, we identified the contexts in which children spoke and the topics they discussed as reported in the studies in question.

3 Findings

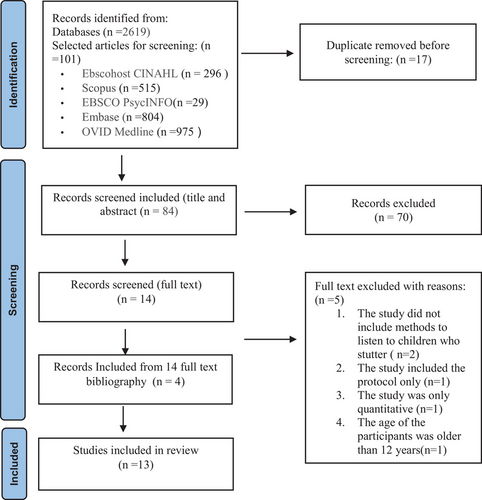

The PRISMA (Page et al. 2021) flow diagram in Figure 1 shows the study selection, which resulted in 13 studies to be included in this review. The initial search in the aforementioned databases yielded 2619 studies. One hundred and one were uploaded to the reference management software EndNote and Rayyan. Duplicates were removed and resulted in 84 studies, of which 25% (21 studies) were screened by the second and third authors. The percentage of agreement between the reviewers was 100%. After a full-text review, it was concluded that 13 out of 18 studies met the inclusion criteria with a consensus rate of 100%.

Eleven studies utilised mixed methods, and two utilised qualitative methods, with seven conducted in the United Kingdom, two in Australia, one in Canada, one in the United States, one in Greece, and one in Japan.

3.1 Study Purposes

The stated study's purposes varied across studies. For instance, Lau et al. (2012) aimed to understand the experiences of SCWS regarding their parental upbringing and interactions with both parents and peers. Prince et al. (2022), Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017), Fourlas et al. (2022), Gerlach et al. (2019), Turnbull (2006) and Carey et al. (2014) all explored the perceptions of SCWS, and its impact of the intervention provided. Iimura et al. (2021) focused on exploring the requests made by SCWS to people surrounding them. Moreover, studies conducted by Fourlas et al. (2022), Gerlach et al. (2019), Moïse-Richard et al. (2021), Prince et al. (2022), Carey et al. (2014) and Rodgers et al. (2020) explore the children's experiences, emotions, opinions on progress, satisfaction and the realisation of their aspirations. Notably, studies by Prince et al. (2022), Rodgers et al. (2020), Berquez et al. (2015) and Cooke and Millard (2018) specifically explored the children's aspirations to achieve their most important outcome. Finally, Berquez et al. (2011) explored children's perspectives on school support.

3.2 Locations

Data collection locations exhibited variability, encompassing clinical settings, residential environments, educational institutions and community contexts. However, three studies, namely Rodgers et al. (2020), Berquez et al. (2011) and Moïse-Richard et al. (2021), did not provide specific information about the data collection sites for children. Additionally, none of the studies clarified whether the choice of data collection space was determined by the children themselves.

3.3 Characteristics of the Participants

The 13 studies included 232 participants who stuttered age between 6 and 18 years, a range that encompasses the target age group of this review (6–12 years) (Table 3). Nine studies explicitly stated the number of targeted participants who were school-age 6–12 years (#86 in total). Sample sizes varied, with a minimum of one participant (Turnbull 2006; Fourlas et al. 2022) and a maximum of 64 participants, 43 of whom were school-age (Iimura et al. 2021).

3.4 Data Collection Methods to Elicit Voice

All the studies used one qualitative method to elicit the children's voices, with Prince et al. (2022) using three and Fourlas et al. (2022) using four methods (See Table 3 and Appendix A). In the 13 studies, a total of 14 different methods were employed to elicit the voices of SCWS (Table 4). The most prevalent method employed was open-ended questions, within semi-structured interviews. The predominant mode of response was verbal, utilised in eight of the methods, while four utilised written responses, and one employed drawing graphs (Fourlas et al. 2022). One study noted that their method involved self-reporting (Moïse-Richard et al. 2021). However, they did not explicitly specify whether the children answered verbally, non-verbally or in another mode of response. Furthermore, it was not clear whether the questions were read aloud by the participants or read by the researchers.

3.5 Purpose of the Methods

Iimura et al. (2021) employed a questionnaire to identify their potential requests to people around them. Prince et al. (2022) aimed to gauge the participants' progress in therapy. Rodgers et al. (2020) and Berquez et al. (2015) explored therapy expectations or hopes. Fourlas et al. (2022) asked children to express feelings about stuttering using emotional graphs, explored their therapy expectations, and conducted structured interviews to explore the child's perspective. Fourlas et al. (2022) also examined participants' aspirations before therapy and the influence of thoughts and emotions through cognitive cycles, as well as their experience with the Lexipontix program. Lau et al. (2012) focused on the child's life experiences and reflections on stuttering with questions related to school, peers, relationships and parental involvement. Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017) explored participants' points of view and experiences nine months after the intervention. Gerlach et al. (2019) aimed to comprehend how participants attributed meaning to their experiences at the National Association of Young People Who Stutter (FRIENDS) convention, while Moïse-Richard et al. (2021) collected feedback and suggestions for future development of the therapy. Carey et al. (2014) evaluated satisfaction with Webcam treatment delivery. Cooke and Millard (2018) and Berquez et al. (2011) respectively used the Delphi method to determine what children who stutter consider the most important therapy outcomes and the essential knowledge needed to support a stuttering child in school. Finally, Turnbull (2006) used semi-structured interviews to gather feedback from SCWS three months after their intervention.

3.6 What the Children Said About Their Talking

This review primarily found a noticeable lack of studies that explore children's viewpoints exclusively. Out of all the studies analysed, Berquez et al. (2015) were the only ones that explored children's perspectives on speaking in school as part of their study. The participants demonstrated a strong desire to speak out, respond to inquiries and participate in group discussions, highlighting their determination to overcome speech-related difficulties in school settings. Furthermore, Turnbull's case study (2006) briefly covered the topic in an interview with girl who stutter. The participant reported that the other students listened more during her conversations following the intervention. Additionally, she noted that after the intervention, everyone in the class noticed how challenging it was for her to speak. Despite the intervention, some children continued to bully her about her speech, but she now feels less bothered by it. Berquez et al. (2011) also discussed SCWS's perspectives on their speech. However, whether the statements originated directly from the children or other study participants was unclear. Additionally, part of their study involved quantitatively rating statements, which was not the focus of our review.

The other studies included in this review covered different topics related to stuttering rather than speaking. Lau et al. (2012) and Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017) offered perspectives on the psychological impact of stuttering on children. Lau et al. (2012) highlighted the experience of social isolation and dissatisfaction resulting from stuttering, compounded by difficulties establishing friendships in a school setting. In contrast, participants experienced increased comfort in speaking with their peers following the interventions, indicating positive social adaptations. Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017) reported changes in children's perceptions after undergoing speech therapy, noting that speaking at a slower pace improved their speech's smoothness. Participants also reassessed their perception of stuttering as a special need, demonstrating changing viewpoints after receiving treatment.

Participants in the Lexipontix Programme reported improvements in classroom participation and reduced phone-related anxiety, indicating enhanced speech fluency following therapeutic interventions (Fourlas et al. 2022). According to Gerlach et al. (2019), participants reported increased confidence when discussing stuttering following a convention. Witnessing others manage their stutter with confidence positively influenced their perceptions despite occasional challenges resurfacing post-convention. Moïse-Richard et al. (2021) participants found it easier to speak in an empty virtual reality room, which they reported also helped them prepare for potential laughter or reactions from others.

4 Discussion

This review explored the qualitative methods used to understand the perspectives of school children who stutter (SCWS), focusing specifically on how their voices and experiences are captured. Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria, and among these, only five studies had a primary focus to investigate (Berquez et al. 2011, 2015; Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017; Cooke and Millard 2018; Rodgers et al. 2020). The remaining eight studies had different objectives, primarily centred on assessing therapy outcomes (as depicted in Table 1). It is worth noting that even some of these five (Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017; Cooke and Millard 2018; Rodgers et al. 2020) did not explore the perspective of SCWS on their stuttering condition.

Lundy's (2007) framework encompasses the dimensions of Space, Voice, Audience and Influence, and Hart's (1992) Ladder of Participation is used to frame the extent and manner SCWS were involved in the research. Researchers and professionals can effectively engage children by utilising Hart's (1992) Ladder of Participation. This framework provides a conceptual structure for comprehending the various degrees of people's involvement in decision-making processes, ranging from non-participation (level 1) to full partnership (level 8).

4.1 Space

The concept of ‘Space’ in Lundy's (2007) framework is a mechanism that affords children the opportunity to articulate their perspectives. Emphasis is placed on the proactive involvement of participants who were given the chance to express their willingness to engage in these Spaces. Furthermore, it pertains to the tangible and intangible surroundings in which children and adolescents are positioned and the extent to which these surroundings can either enable or impede their capacity to articulate their perspectives and ensure their opinions are acknowledged (McAllister et al. 2022). This necessitates the presentation of information in a child-friendly manner and the implementation of methods that actively engage children in the research process (Olçay Gül and Vuran 2015). All studies provided ‘Space’ for the SCWS. While the majority of included studies provided consent forms for the parents and assent forms for the children (e.g., Lau et al. 2012; Iimura et al. 2021; Prince et al. 2022; Carey et al. 2014; Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017), six studies lacked clarity in this aspect (Berquez et al. 2011, 2015; Cooke and Millard 2018; Fourlas et al. 2022; Gerlach et al. 2019; Rodgers et al. 2020). Notably, Moïse-Richard et al.’s (2021) study completed assent forms with children older than 13; however, for younger children, they collected the consent form from the participants’ parents only. Moreover, it was unclear in the studies how the researchers collected the consent assent, for example, in person, online or over the phone. Turnbull (2006) did present the information about the study to the child verbally and requested assent verbally by asking if she was willing to join.

Furthermore, no information was provided on whether children had any choice in choosing the location of the data collection. Offering a child a choice between online or face-to-face interviews or between having the interview in their home or in the clinic could influence their participation and willingness to express themselves. The surroundings can influence the children's participation (McAllister et al. 2022). However, it is worth noting that the researcher might have limited resources or space to give children a choice.

4.2 Voice

The second dimension of Lundy's (2007) framework, denoted as ‘Voice’, explores the extent to which children are afforded the opportunity to articulate their perspectives. Furthermore, researchers are urged to provide children with essential information to formulate opinions and offer diverse avenues for self-expression, enabling them to choose the method that best suits them (Carroll and Twomey 2021). All the studies in this review employed one or more qualitative methods to elicit children's voices, aligning with the perspective of Lyons et al. (2022). Lyons et al. (2022) posit that the utilisation of qualitative research methods creates a space for children to explore their lived experiences, preferences, and values. However, a predominant focus on verbal or written modes of response is evident in the studies, and no study mentioned if they gave the children the choice of method of communication. This lack of choice may lead to lack of potential diversity and richness offered by alternative methods, such as visual methods, including photography and drawing activities, walk and talk activities, puppets and scrapbooks (Gillett-Swan and Sargeant 2019; Hanna 2022; Lyons et al. 2022). The combination of diverse methods can be used to elicit in-depth discussion from participants about a topic and ensure the inclusion of a range of voices (Carroll and Twomey 2021; Lyons et al. 2022; McAllister et al. 2022). An exception is noted in the study by Fourlas et al. (2022), which demonstrated variability in methods for collecting children's perspectives. However, clarity was lacking, particularly regarding the utilisation of certain methods, such as the emotion graph (Fourlas et al. 2022). The use of diverse and creative communication methods supports children's expression, ensuring the inclusion of a range of voices (Carroll and Twomey 2021; McAllister et al. 2022). Furthermore, the implementation of participatory methods is advocated to establish parity in relationships and mitigate power differentials in research, ensuring a shared responsibility and knowledge-sharing between researchers and participants (Merrick et al. 2019).

4.3 Audience and Influence

In Lundy's (2007)’s framework, ‘Audience’ is where children's views are listened to, and ‘Influence’ recognises that their views are given due weight. The framework centres on the recognition and active integration of children's perspectives, evaluating the extent to which their opinions are valued, deliberated upon and contribute to transformative change. Although all the included studies listened to the SCWS, the studies need more specific information regarding the implementation or response to SCWS perspectives, as there are uncertainties about any subsequent actions. Notably, Moïse-Richard et al.’s (2021) study employed a Likert scale (0–10) for children to respond to each question. The researchers utilised these responses to generate a hierarchy of feared reactions tailored to individual participants throughout their engagement in an immersive virtual classroom environment, which gives weight to the children's voices. Furthermore, Berquez et al. (2011) and Cooke and Millard (2018) as a part of the Delphi method, included the children in the process of question formulation as part of their research.

Nevertheless, some researchers acknowledged the importance of considering children's perspectives and their potential influence on treatments in studies such as those conducted by Fourlas et al. (2022), Moïse-Richard et al. (2021), Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017) and Carey et al. (2014). These studies facilitated the incorporation of children's perspectives in discussions about the development of their individual treatment plan, aiming for a more comprehensive understanding of the child. However, only two studies Berquez et al. (2011) and Cooke and Millard (2018) involved the children's voices in developing the methods or methods to elicit their voices. Additionally, the included studies advocate for the active engagement of SCWS in therapeutic environments and future research endeavours, as articulated by Prince et al. (2022), Fourlas et al. (2022) and Caughter and Dunsmuir (2017).

4.4 Hart's Level 4 Assigned but Informed

Seven out of 13 studies scored as level 4 ‘assigned but informed’, which happens when children comprehend the project's goals, are aware of who decided on their involvement and the reasons behind it, have a meaningful role rather than a superficial one, and volunteer for the project after understanding its details (Berquez et al. 2015; Carey et al. 2014; Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017; Iimura et al. 2021; Lau et al. 2012; Prince et al. 2022; Turnbull 2006). Four studies (Fourlas et al. 2022; Gerlach et al. 2019; Moïse-Richard et al. 2021; Rodgers et al. 2020) uniformly featured instances where children are given a voice but have limited choice or input (Lundy 2018), categorising them as level 3 ‘Tokenism’ on Hart's ladder. This level was chosen because there was no clear information regarding the children's understanding of the research process and consent to join. This observation corresponds with the potential tokenistic nature of decision-making processes when individuals with speech, language and communication needs are included (Lyons et al. 2022). However, according to Lundy (2018), engaging in tokenistic participation might offer specific children a beneficial learning experience.

4.5 Hart's Level 5 Consulted and Informed

Two studies were at level 5 on Hart's ladder as the children were consulted to generate questions and generated statements following the Delphi method included in the studies (Cooke and Millard 2018; Berquez et al. 2011). Bedoin and Scelles (2015), argue that it is crucial to include participants actively in the development and evaluation of first-person approaches; this not only enhances client-centred practices but also highlights possible deficiencies in their research and practice

4.6 Children's Perspectives on Their Stuttering

Berquez et al. (2015) explored children's perspectives on speaking as part of their study. Their participants expressed a strong desire to speak more and overcome the challenges they face talking in school, such as speaking and reading more out loud in the classroom and participating in tasks involving speaking in school.

Furthermore, Turnbull's (2006) intervention helped raise awareness of the participants’ school friends’ understanding of what she was going through, and that they should listen more to her.

Moreover, the other included studies also provide valuable insights into SCWS's diverse experiences and perspectives. They include problems in different settings (Lau et al. 2012), changes for the better after interventions (Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017; Fourlas et al. 2022) and the possible benefits of communication-focused environments like virtual reality (Moïse-Richard et al. 2021). Overall, these results show that children's experiences with stuttering are multifaceted. However, this review draws attention to a significant lack of qualitative research relating to the perspectives of SCWS regarding their stuttering.

4.7 Research and Clinical Implications

This review highlights the importance of involving school-aged children who stutter (SCWS) in both research and clinical practice, recognising their distinct perspectives, which differ from those of adults or parents (Gallagher et al. 2019; Goldbart and Marshall 2011; Markham and Dean 2006; Markham et al. 2009; Roulstone and McLeod 2011; Salvo and Seery 2021). Future research should focus on child-led approaches that explore SCWS's nuanced experiences and aspirations, challenging adult-centric assumptions.

Clinically, speech-language therapists (SLTs) are urged to reflect on their professional and ethical responsibilities when working with children (McAllister et al. 2022). This includes considering the Lundy Model and reflective questions proposed by McAllister et al. (2022) to guide their own practice and professional development. The Lundy Model (2007) offers a practical framework for ensuring genuine participation in both research and practice by promoting space, voice, audience and influence. This approach supports the obligations set out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (United Nations 1989), particularly Article 12, which asserts the child's right to be heard. By prioritising children's voices, SLTs can ensure that children's lived experiences remain central to interventions (McAllister et al. 2022).

SLTs are also encouraged to use multimodal, child-friendly tools such as drawing, photography and storytelling (Bölte 2023; McAllister et al. 2022). These approaches can help children express how stuttering affects their daily lives, resulting in more individualised and meaningful interventions (Bedoin and Scelles 2015; Bölte 2023).

Therapists should further reflect on their communication styles during therapy, ensuring that interactions are respectful, accessible and empowering. Including children in decision-making—rather than relying solely on parent perspectives—can strengthen therapeutic relationships, improve outcomes and uphold children's rights (Bedoin and Scelles 2015; Brundage et al. 2021; Carroll and Twomey 2021; Dockett and Perry 2007; McAllister et al. 2022; Merrick et al. 2019; Tichenor, Herring et al. 2022).

Finally, bridging research and practice is essential for advancing evidence-based, person-centred stuttering support (Chun et al. 2010). SLTs should engage with and contribute to research that values children's voices, ensuring authentic participation rather than tokenistic. Future studies should examine how participatory methods influence both clinical outcomes and long-term well-being. By actively involving SCWS in shaping their support, SLTs can foster more ethical, effective and empowering clinical environments.

4.8 Strengths and Limitations

This review fills an important gap in the literature by highlighting the methods used in studies that explore the perspectives of school children who stutter (SCWS) and their experiences with stuttering. It focuses specifically on research that uses qualitative and qualitative components of the mixed methods. The review was conducted in a systematic way and included a peer review process and Endnote Desktop 20 (2023) and Rayyan (Ouzzani et al. 2016) to manage references and to facilitate screening. However, the search strategy's predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria may have inadvertently overlooked or excluded relevant grey literature, as the search did not encompass dissertations or theses. The absence of specific articles focusing on the qualitative exploration of the perspectives of SCWS represents a notable gap in the literature. Due to the limited number of studies found, the studies included did not categorise participants into distinct age groups, potentially overlooking nuances in the perspectives of children versus older school-age children age more than 13. This limitation underscores the importance of future research considering not only what is analysed but also how it is analysed, providing a more nuanced understanding of the diverse perspectives within the broader category of school-age children who stutter.

5 Conclusion

This study aimed to elucidate the methods employed in eliciting perspectives from school children who stutter (SCWS) and to examine the nature of these perspectives regarding their speech experiences. The review included 13 studies, and findings revealed a diverse array of methods for accessing the viewpoints of children who stutter. However, it is imperative for researchers to extend beyond tokenistic forms of participation, recognising the necessity of authentic inclusion of children's voices. The restricted modes of response in some studies underscores the need for researchers to innovate and personalise inclusive methodologies for each young participant, investing the necessary time for meaningful engagement. While acknowledging the substantial time and resource implications, it is increasingly untenable to dismiss such approaches as overly challenging or analytically complex. Every child possesses the right to express their viewpoint, a right that must not be contingent upon perceived communication capacities or expressive skills (United Nations 1989). Furthermore, understanding these viewpoints is essential for creating individualised therapies to improve stuttering children's well-being and communication abilities. Future research endeavours should prioritise seeking the perspectives of underrepresented groups, including children who stutter and those under the age of 13, to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the experiences and perspectives of children who stutter.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Appendix A: METHODS EXTRACTION TABLE

| The data collection methods and techniques to elicit voice | The mode of response | The purpose of the method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1- | Questionnaire with open and closed questions (Iimura et al. 2021). | Written | The questionnaire sought participants’ potential requests to their friends, classroom teachers, and families. |

| 2- | A- The is solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) worksheets:adapted from De Shazer (1985) by Rodgers et al. (2020) a blank space for clients to free list their responses to a set of verbal prompts provided by the SLP related to their best hopes (open ended question with prompt). | Written | Best hopes that will or achieved from therapy. |

| B- Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) scaling (de Shazer 1985; Berquez et al. 2015). | |||

| 3- | Emotion-graph completed by parents and child (Fourlas et al. 2022). | Nonverbal | Emotional responses of children to their stuttering experience and draw their emotional graph. |

| Circle the emotion (word) and the child constructs his/her own “photograph” of emotions about stuttering. | |||

| 4- | Individual semi-structured interviews using open-ended and prompt questions (Lau et al. 2012). | Verbal | Semi-structured interview focused on stuttering, with additional questions on school, peers, and parents. |

| 5- | Semi-structured interviews 9 months post-therapy using eight open-ended and prompt questions (Caughter and Dunsmuir 2017). | Verbal. | To explore the viewpoints and actual experiences of the participants after the intervention. |

| 6- | Structured interview using SFBT questions with parents and child (Fourlas et al. 2022). | Verbal | A structured interview to explore the child's best hopes and expectations from therapy. |

| Three open-ended questions. | |||

| 7- | Structured interview with child (Fourlas et al. 2022). | Verbal | A structured interview to explore the child's perspective on stuttering. |

| Open-ended question not specified. | |||

| 8- | Online semi-structured interviews, including open ended questions on seven topics (Gerlach et al. 2019). | Verbal | To comprehend how participants made meaning out of their experiences at the FRIENDS convention. |

| 9- | Feedback about the participants experiences (Moïse-Richard et al. 2021). | Not clearly specified | Participants’ feedback about their experience and future development ideas. |

| Open ended questions not saponified. | |||

| 10- | Post-treatment semi-structured interviews for adolescents (Carey et al. 2014). | Verbal | Satisfaction with Webcam treatment delivery. |

| Eight open ended question. | |||

| 11- | Semi structured interview (Prince et al. 2022). | Verbal | To identify an event where talking was challenging. |

| Open ended question. | Explore how stuttering children's ideas and emotions affect their actions. | ||

| 12- | Structured interview with child using Alliance Interview Protocol (Fourlas et al. 2022). | Verbal | The children experience and changes the Lexipontix program. |

| Three open ended questions. | |||

| 13- | Delphi method: Stages 2 and 3 (Goodman 1987; Berquez et al. 2011; Cooke and Millard 2018). | Written | To create statements based on the questions formulated by each of the focus groups. |

| 14- | Semi structured interview (Turnbull 2006). | Written | Feedback 3 months after presentation (intervention) about the CWS experience after the intervention. |