Values motivating water governance in Delhi

Abstract

Values of individuals and organizations involved in decision-making processes form the basis for prioritizing outcomes in water governance. The novelty of this study lies in applying values to a specific decision-making context. It aims to assess the prioritized water governance outcomes and the underlying value systems shaping the actions of the primary water utility responsible for water governance in Delhi, the Delhi Jal Board (DJB). The paper will critically examine the policies and acts of the DJB that drive water governance in Delhi at present, utilizing a values-based framework in conjunction with secondary literature and expert interviews, to draw a picture of the values reflected. The study does not substantiate the notion of economic values dominating the water-related decisions; rather, recent policy guidelines indicate prioritization of equitable and fair distribution of water. Findings of this paper show that making the values explicit is largely disregarded in formulating water acts and policies, and values are never elucidated in the public domain, doing which can encourage water policies and practices that are socially, economically, and ecologically viable in the long run. It is expected that this paper will generate a discussion on water values being an integral part of water governance discourses.

1 INTRODUCTION

Values are moral codes that decision makers pursue when faced with situations demanding priority setting and trade-offs (Berg & Jacobs, 2016; Groenfeldt, 2019; Rokeach, 1973). Values implicitly and explicitly produce variegated impacts and outcomes for different categories of people. In this paper, values are held to be those cognitive structures, which steer day to day lives of human beings (Feather et al., 1996; Groenfeldt & Schmidt, 2013; Lewin, 1997; Rohan, 2000). Values, therefore, are central to human conduct, and lived reality does not stand independent of human values (Fischer, 2017). Value systems of individuals in organizations are more than often adapted from societal structures and processes (Asthana, 2009; Groenfeldt, 2017). Values are, in fact, shaped by the existing social, political, ecological, and economic realities, the major causes of innovations leading to radical changes in social systems (Gunderson & Holling, 2002).

The values of individuals and organizations involved in decision-making processes form the basis for prioritizing outcomes in water governance and tale-informed decisions (Jacobson et al., 2013; Jiménez et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2024; Pigmans et al., 2019; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development 2018). This study explores how applying a values framework to a particular decision-making context can provide insights into the decision-making processes, revealing the governance outcomes the city is aiming for and identifying necessary improvements. Although values cannot be separated from policy framing and implementation, there is a lack of scholarship that demonstrates this relationship in Delhi. The study examines water governance in Delhi, the capital of India, to assess the alignment of its intended outcomes with the desired outcomes of the values framework presented. This framework is used as a heuristic to decipher and comprehend the value base of the Delhi Jal Board (DJB), the water utility entrusted with the responsibility of water supply and sanitation in Delhi, by analyzing relevant acts and policies for the values they uphold.

Introduction has been divided into two sub-sections. In sub-section 1.1, the paper reviews the relationship between water values and water governance as a framing for examination of the case study, and sub-section 1.2 provides an overview of the water supply and use in Delhi, before it commences with the analysis of the values backing the critical acts and policies in Delhi.

1.1 A review for comprehending water values in water governance

Values impact what relative importance humans accord to different water uses, impacts, and outcomes (Groenfeldt, 2019). Since water is a political good (Schouten & Schwartz, 2006), it cannot exist without its ideological underpinnings constructed based on human values. Managing water resources is a “wicked problem” (Frame & Russell, 2009; Hearnshaw et al., 2011; Lockwood et al., 2010; Rittel & Webber, 1973), and its governance as such requires ethical and value-based decision making (Campbell, 2002; Groenfeldt, 2019; Lockwood et al., 2010; Nilay, 2021). Water governance can either be related to the process of decision making through different mechanisms or institutions or the outcomes of decision making (Allan, 2001; Jiménez et al., 2020; Lautze et al., 2011). As a process, Rogers and Hall (Rogers & Hall, 2003) described water governance as “…the range of political, social, economic and administrative systems that are in place to develop and manage water resources and the delivery of water services, at different levels of society.” Water governance can also be described as performing specific functions from the stage of policy formulation to implementation, with the intent of achieving value-driven desired outcomes by individuals and organizations” (Jacobson et al., 2013; Jiménez et al., 2020). The focus of this study is on integrating values into the implementation of water governance to enhance the likelihood of achieving intended outcomes.

Values pervade all approaches of water governance. The foundation of water governance cannot be laid only based on economic values alone which is a common approach in a utilitarian scenario (Chamberlain, 2008; Groenfeldt 2017, 2019; Gunderson & Holling, 2002; Shaw & Francis, 2014). Values such as empathy and equity are equally significant as an outcome of water governance as they empower the marginalized groups by ensuring them at least the basic human rights (Abbott & Vojinovic, 2010; Doorn, 2018; Roy, 1999). An understanding of the social and ecological conditions of the place is essential to identify the values that will add up in a particular setting (Akamani, 2016; Akhmouch & Correia, 2016; Groenfeldt, 2019; Harrison, 2003; OECD, 2015; Pahl-Wostl, 2017). The values steering water governance should thus be analyzed along substantive dimensions such as environmental, ecological, social, cultural, and economic values (Bauer & Smith, 2007; Groenfeldt, 2019; Haileslassie et al., 2020; Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2006a; Mostert, 2019; Schulz, 2019).

The concept of values in governance is relatively less explored. Governance-related values refer to the values that are believed to attain effective water governance by achieving the idealized goals set out by a water organization, expressed as desirable ends by individuals and groups of that organization (Schulz, 2019). Values in governance guide the societal actors involved in the governance of water to evaluate situations and select their policies and actions accordingly (Groenfeldt, 2017; Groenfeldt, 2019; Groenfeldt & Schmidt, 2013; Kooiman & Jentoft, 2009).

Often, conflicting interests decide the values that are finally upheld in policy-making decisions. The direction in which an individual pursues their moral goals is ultimately enacted in practice and embodied in institutions such as water laws and water management infrastructure (Asthana, 2009; Gunderson & Holling, 2002; Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz et al., 2012). Ideal values are often observed in public discussions and policy documents, while actual values that motivate actual human behaviors are different from stated values (Asthana, 2009; Mostert, 2019). For an effective water governance, the actors need to navigate through the socio-ecological norms and bring them into consideration while framing plans and policies (Asthana, 2009; Groenfeldt, 2017; Groenfeldt, 2019).

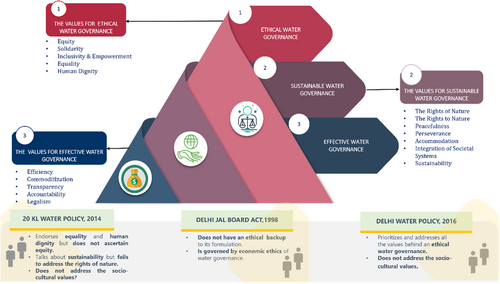

Values are sometimes listed explicitly as properties of good governance (Biswas & Tortajada, 2013) but mostly left implicit. Our discussion focuses on how water governance should function to maximize the likelihood of achieving the intended outcomes of good governance. We gather that prominent scholarships regarding good governance, including the UN good governance principles (UNESCAP, 2009), the OECD principles (OECD, 2015), Allen Rogers' principles of “effective water governance” (Rogers & Hall, 2003), all emphasize similar attributes that should be reflected from water governance such as transparency, accountability, participatory, responsive, consensus oriented, following the rule of law, equity, inclusive, effective, and efficient, sustainable, coherent, and integrative (Graham et al., 2003; Grönwall et al., 2010; Training Manual and Facilitator's Guide 2017; United Nations General Assembly, 2010; United Nations General Assembly, 2015). Drawing from the existing literature, we have categorized desirable governance values into three categories by corresponding values with desirable governance outcomes (Groenfeldt 2017, 2019; Schulz et al., 2017a; Schulz, 2019). We consider that water governance should comply with the principles of good governance and respond to place-based social, economic, and cultural needs and particularities.

In addition to drawing on the literature on good governance for classifying the set of values, we have also related the values to the Schwartz's (1992) Value Theory. Schwartz's theory provides a more psychologically grounded framework, while other governance literature focuses more on institutional or political dimensions. Schwartz's theory of values provides a framework for understanding human priorities and decision-making. He proposes that values stem from three fundamental needs: individual well-being, social cohesion, and the survival of groups. Within this framework, he identifies key motivational values, including benevolence, universalism, achievement, power, and security. These values are interconnected in a circular structure, where some complement each other while others present conflicts. For instance, values that emphasize altruism and global concern tend to align, whereas those centered on personal success and dominance may sometimes oppose those focused on fairness and collective welfare.

Our framework connects different types of water governance to Schwartz's values in a clear way. Ethical Water Governance is about caring for others and promoting fairness, linked to Benevolence and Universalism. Sustainable Water Governance focuses on protecting the environment and ensuring long-term stability, aligning with Universalism and Security. Efficient Water Governance is about being competent, organized, and maintaining control, which ties to Achievement and Power.

Legalism fits into Efficient Water Governance because its main role is to set rules and structures for managing water effectively. While it can have ethical aspects, its key purpose is maintaining order and control, just as Schwartz's theory connects legalism with Power and Security.

The first category of values includes the values that aim for an “equitable, inclusive and ethical water governance.” These values are equity, solidarity, inclusivity, empowerment, equality, and human dignity. This set of values is termed as “The Values for Ethical Water Governance.”

The second category of values aims for “sustainable water governance” and includes the rights of nature, the right to nature, peacefulness, perseverance, accommodation, and integration of societal systems. This set of values is termed as “The Values for Sustainable Water Governance.”

The third category includes the values of efficiency, commoditization, transparency, accountability, and legalism and aims at achieving an “efficient water governance.” This category is termed as “The Values for Effective Water Governance.”

None of these categories of water values can influence the outcomes of the water governance independently; they are often present simultaneously with varying degrees of influence. The three categories of values are summarized in Table 1 below. Making water values apparent is expected to contribute to improving the water policy-making mechanisms and processes. These potential benefits would include multiple uses of water resources, transparency in governance, integrated analyses, and strategic development planning.

| Water values | Elucidation |

|---|---|

| The Values for Ethical Water Governance | |

| Equity | Equity means recognizing different circumstances of citizens and allocating the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome. Fair distribution of resources like potable water in cities so that everyone can maintain and improve their well-being. It also means fair decision-making and implementation processes, serving the interests of diverse humans. Aligns with Schwartz's Universalism (social justice, equality). Primarily an end, reflecting concern for the welfare of others, but also a means to social stability |

| Solidarity | Alliance of the water utilities with the public as opposed to corporations for economic gains. Reflects Schwart's Benevolence (concern for the welfare of others). Primarily an end focusing on well-being of the society. |

| Inclusivity & empowerment | Participation of all stakeholders in water policy formulation and enactment of laws after meticulously considering peoples' views and vulnerabilities. Connects to both Benevolence and aspects of Universalism by valuing the participation of all stakeholders in policy processes. Both a means to create robust policies and an end, recognizing the intrinsic importance of participation. |

| Equality | Equal treatment of all the diverse groups of society without any prioritizations or exclusions. Equal access to water irrespective of class, income, or location. A core component of Schwartz's Universalism, ensuring impartial treatment and access to water resources, irrespective of social differences. Primarily an end, but also a means to foster social harmony. |

| Human dignity | Universal access to water being provided to all citizens by the water utility so that all citizens can behold this basic human right with respect. Aligned with Benevolence and Universalism, emphasizing the fundamental right to water as essential for human respect and well-being. Primarily an end, reflecting a fundamental ethical principle. |

| The Values for Sustainable Water Governance | |

| The rights of nature | By addressing the loss of global biodiversity and the consequences of climate change, the rights of nature ensure protecting and ensuring water for the climate, the environment, and people, thereby enhancing water governance. For e.g. The Universal Declaration of River Rights,2020 have recognized rivers as a rights-bearing entity (Eckersley, 2023; Kauffman & Martin, 2021). Humans have an obligation to pro-actively work for the protection of nature and coexistence. Extends Universalism to include the environment, acknowledging the intrinsic value of nature and the need for its protection in water governance. Both a means to ensure ecological sustainability and an end, valuing nature for its own sake |

| The rights to nature | Humans have the right to benefit from nature's abundance (water resources) and experience a good quality of life (Alves et al., 2023). While related to Universalism, it emphasizes the human-centric aspect, focusing on the right to benefit from nature's resources for a good quality of life. Primarily an end, centered on human well-being |

| Peacefulness | Maintaining a peaceful situation between and among diverse groups of water users and stakeholder organizations. Can be linked to Security (harmony, stability) in Schwartz's theory, promoting social stability among water users. Both a means to prevent conflict and potentially an end, valuing harmonious relations. |

| Perseverance | Policy makers must pursue water and planning policies for a long period of time to make a difference. Reflects the importance of long-term planning and policy commitment, aligning with the stability aspect of Security. Primarily a means to achieve enduring policy outcomes. |

| Accommodation | Assimilate new experiences into our worldviews, adjusting our mental structures like climate change adaptation in water planning. Demonstrates Self-Direction (adapting to changing circumstances) by emphasizing the need to adjust to new realities like climate change in water planning. Primarily a means for resilience. |

| Integration of societal systems | Identifying the social and ecological conditions of a place is to identify the values that will add up in a particular setting. Highlights the need to consider social and ecological contexts, linking to Universalism's emphasis on understanding and interconnectedness. Primarily a means to ensure context-relevant governance. |

| Sustainability | Planning for the utilization of water resources in a way that ensures equal access for both present and future generations. Encompasses Universalism (long-term welfare) and Security (stability for future generations), advocating for equitable resource use across generations. Both a means and an end, valuing both resource management and intergenerational fairness. |

| The Values for Effective Water Governance | |

| Efficiency | Policies should be cost-effective, making the best possible use of available resources. Aligns with achievement (competence, effectiveness) in Schwartz's framework, focusing on optimizing resource use and problem-solving. Primarily a means to achieve effective outcomes. |

| Commoditization | Water, like other commodities, is treated as a commodity having a price in the marketplace to be freely bought and sold by private parties. Reflects a tension with Schwartz's framework. While it can relate to Achievement (economic efficiency), it potentially conflicts with Universalism and Benevolence if it undermines equitable access. Primarily a means to financial sustainability, but raises ethical considerations. |

| Transparency | When decision-making processes are made comprehensible and visible to the public, whatever may be their content and nature. A procedural value that serves Achievement (accountability) and can enhance Universalism by enabling scrutiny and participation. Primarily, a means to ensure responsible governance. |

| Accountability | When organizations involved in water governance take responsibility for their decisions and are answerable to the citizens at any point of time. Like Transparency, it supports Achievement by emphasizing answerability and responsibility. Primarily a means to ensure good governance and ethical conduct. |

| Legalism | Impartial legal frameworks that can protect the vulnerable sections of society and the natural resources at the same time. These frameworks do not discriminate against anyone and promote basic human rights (Jiménez et al., 2020; OECD, 2015). Primarily, a means to security (order, rule-following) by providing the framework for regulation and enforcement. Can have ethical implications, but mainly serves to maintain order. |

- Source: Author

Values can serve as both means and ends. Some values are crucial as they help achieve desirable outcomes acting as means to an end while other values are important in their own right, representing the ultimate ends of governance. Transparency and accountability can fall on different points of this spectrum, with their role depending on the specific context in which they are applied.

Transparency in water governance refers to the degree to which information regarding water resources, governance processes, and decision-making is accessible, clear, and understandable to all stakeholders, including citizens, government agencies, and civil society organizations which emphasizes that transparency is a means to ensure that stakeholders can scrutinize decisions, participate effectively, and hold authorities responsible.

Accountability in water governance implies that those responsible for water management and service delivery are answerable for their actions, decisions, and performance, and are subject to scrutiny and potential consequences.” Accountability is both a means to improve performance and deter corruption and an end, ensuring that power is exercised responsibly.

Before analyzing the water values backing water governance in Delhi, the study provides a factual overview of water supply and use in Delhi (Figure 1).

Source: Author

.1.2 Introduction to case study area

DJB is the primary stakeholder organization responsible for supplying water and provisioning sanitation services in Delhi. It holds significant authority and plays a crucial role in taking decisions that govern accessibility to basic amenities in diverse categories of developments. The DJB is not only tasked with the responsibility of procurement and distribution of water but is also expected to provide equitable access to water to all sections of society.

Delhi is faced with the challenge of water insecurity as it procures 90 percent of its raw water from the neighboring states, producing uncertainty in the supply of potable water for the city residents (Planning Department, 2023). For obtaining raw water, Delhi relies majorly on surface water resources, mainly river Yamuna, and to some extent on groundwater resource. Yamuna's deteriorating water quality has been a matter of concern for Delhi over the years. Yamuna receives 79% of its total pollutant load from Delhi, in approximately 48 km stretch that flows within the NCT and represents only 2% of the Yamuna's total length (Central Pollution Control Board, 2006, 2013; Patel et al., 2020). The major contributor of this pollution is the untreated sewage that flows into Yamuna through 22 drains between Wazirabad Barrage and Okhla Barrage connected to major industrial estates (Patel et al., 2020). Moreover, groundwater levels are declining at an alarming rate. The rate of extraction of groundwater in Delhi is much higher than the rate of recharge, and groundwater levels have declined by 20–30 m in various locations (Aijaz, 2020; Planning Department, 2023). Moreover, high concentrations of nitrate and fluoride clubbed with high salinity have rendered groundwater unsuitable for human consumption.

The multiplicity of stakeholders involved in the water management system for the procurement of raw water makes it highly complex and poses a constant threat to water security for the residents. The city is characterized by an apparent diversity in housing settlements, comprising of planned developments and unplanned informal neighborhoods, which have a varied access to basic services like potable water and sanitation (Center for Policy Research, 2015). The citizens residing in informal developments like slums, “Jhuggi Jhopdi” clusters,1 and unauthorized colonies2 are deprived of access to basic amenities like water and sanitation. The decision-making processes that underlie infrastructure provisioning officially marginalize the poor by denying them equitable access to basic services (Kumar et al., 2021). As per economic survey of Delhi, 2022–-023, two thirds of Delhi live in sub-standard housing in informal settlements which have been built in violation of land use policies and do not abide by the building by laws (Truelove, 2016, 2018, 2019, 2020). This implies that a large percentage (76.3%) of Delhi's population is excluded from the right to access basic water supply (Delhi Development Authority, 2021) as DJB does not supply water to any area which is built in contravention to any law.

DJB has different provisions tailored for different areas, driven by the level of influence exercised by residents in those specific locales. The daily water supplied to residents living in different zones varies, with the least amount of water being supplied to lower-income areas. Spatial inequality is so deeply entrenched in DJBs water provisioning system that lack of equal opportunities to access and use water services compels the poor to access low quality services via unauthorized and informal means like water tankers, overly priced bottled water, unlicensed ground water extraction or turns them to water thieves from water networks (Center for Policy Research, 2015; Delhi Development Authority, 2021; Planning Department, 2023). On the contrary, the influential areas where most of the powerful politicians and bureaucrats reside; falling within the jurisdiction of New Delhi Municipal Council, the Delhi Cantonment Board, and Military Engineering Services, receive water in bulk from DJB with no metering system in place (Kumar et al., 2021).

Other prominent challenges include high distribution losses, suboptimal working of sewage treatment plants, inadequate use of treated wastewater, decreasing revenue for DJB. The distribution losses at different stages of the water supply system handled by DJB are very high. Fifty-eight percent of water is lost while distribution in the treatment plants, conveyance systems and distribution systems (Planning Department, 2022a).

Sewage treatment plants are not functioning at their optimum levels and are only utilized to only 87 percent of their capacity. As a result, 30 percent of the wastewater remains untreated and falls into river Yamuna directly without any treatment (Agarwal, 2022). At present, Delhi produces 560 million Gallons per Day (MGD) of wastewater (Planning Department, 2023). Out of this 560 MGD, DJB supplies 89 MGD to Irrigation Department, Power Plants, Irrigation purposes to Central Public Works Department and Delhi Development Authority, Flood control and Irrigation Department for various purposes, and 250 MGD is returned to Yamuna, as Delhi is bound to return 250 MGD to River Yamuna under the Upper Yamuna Water Sharing Agreement (Delhi Jal Board, 2016). Hence, we have an available wastewater resource of almost 221 MGD, which is not put to proper use.

Delhi's domestic consumer water tariffs are one of the lowest when compared to several countries of the world. The per capita income of Delhi is ranked at 3rd place among states and union territories and is three times higher than the national average (Planning Department, 2022b). Still, records show that the tariff collected by DJB decreased from Rs 1615.83 crore in 2016–17 to ₹1294.86 Crore during 2022–23 (Planning Department, 2024a, 2024b).

DJB is not well prepared to cater to the present water demand. DJB presents an overestimated figure of water supplied which creates a phony picture of quantity supplied. DJB does not have proper systems in place to measure the actual quantity of water supplied. It supplements its estimates by adding water from other sources (Kumar et al., 2021).

We consider that prioritization of decisions is rooted in values that order and legitimize human conduct towards certain ends and not others (Groenfeldt & Schmidt, 2013; Kooiman & Jentoft, 2009; Maio, 2016; Schulz et al., 2017a). To comprehend the moral goals of major stakeholders who ultimately frame policies and set priorities for water provisioning for different sections of society, it is vital to study the fundamental values that guide these processes (Glenk & Fischer, 2010; Ioris, 2012; Kovel, 2021; Nilay, 2021; Vázquez Rodríguez & León, 2004).

Now that we have a fair understanding of water supply and the critical position of DJB in water governance of Delhi, we will carry out a comprehensive analysis of the values guiding the critically important functions of the DJB. We believe for understanding the values shaping the governance of water in the case of Delhi, analyzing the acts and policies of DJB becomes crucial since it is the government body responsible for water supply and sanitation in Delhi. To set the context for our research, we commence by stating that, neither the policies, acts, and plans of Delhi have ever been examined through the lens of water values nor are water values given due consideration while preparation of important plans and policies, which ultimately determine the quality of life of the citizens. The work by Vandana Asthana is an exception (Asthana, 2009). She explains how policy making is multifaceted and layered with interpretations of social and cultural practices rather than being a linear process. The policy making process in Delhi has been explained with reference to a controversy over awarding the contract of a water treatment plant to a French multinational corporation by government of Delhi back in 2002. This was a pilot project aimed at providing 24/7 universal safe water and sewerage services to the people of Delhi. This study explains how the beliefs and values of societal actors made the decision makers retract their decision of privatizing water supply in Delhi and change their policy. The opposition was driven by the traditional cultural values of having community rights over water bodies and the belief that privatization would increase inequity in access to water.

The study concludes that analyzing water policies and plans through values could provide an opportunity to the decision-makers for improving access to water and sanitation services and encourage water policies and practices that prove to be citizen-friendly and protective of nature in the long run. Pricing of water using market as well as nonmarket values can ensure efficacious, equitable, and affordable access to water. A deeper analysis of values is also necessary because water values show real motivations behind inclusion of certain important aspects of water policies, and the interrelationship between them can facilitate conflict resolution amongst different governance actors.

In this backdrop, our study seeks to analyze the values of DJB to find out the core values backing critical water policies and acts (Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz et al., 2012). Our values' analysis could initiate a process of equitable potable water distribution in the city (Schulz, 2019). However, a major challenge to conduct research on water values is the collection of information from stakeholders who remain reluctant to share deeply held values and the implications of such values on water security.

This paper has been divided into five sections. Introduction is succeeded by a brief exploration of the methods used in Section 2. Section 3 then presents the results of the analysis of relevant significant acts and policies of DJB using the values-framework. Section 4 contains a discussion on the results obtained and the theoretical contributions of the paper. The study is then concluded in Section 5.

2 METHODS

The overall aim of this study is to understand the values that shape the governance of water, using Delhi as a case study. The first objective was to determine what policies have been implemented to govern water in Delhi. The second objective is to analyze key documents to uncover the underlying values that shaped them. The third objective is to understand the perspectives and values of key stakeholders in the governing of Delhi's water. The final objective is to suggest how the findings here can shape more effective policy-making in Delhi and in other cities.

This paper uses a qualitative approach using primary and secondary data to understand the context, processes, and motivations involved in governing water in Delhi and to uncover the values shaping them. The methods consisted of reviewing existing policy documents and selecting keys ones to critically analyze and then interviewing expert stakeholders to further uncover the underlying values and processes. A critical appraisal of plans, policies, and acts of Delhi water authority (DJB) was carried out to identify the pivotal data set. Three key pieces of legislation and policies were chosen that play a major role in the water governance in the NCT Delhi: “The Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998” (The DJB Act, 1998); “The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014”; and “Draft Delhi Water Policy, 2016” (DDWP, 2016) Keeping in mind the aim of our study, we narrowed down on the chosen act and policies as these are the critical documents that lay out the broader terms and conditions to be followed by DJB while supplying water to the masses. These documents were chosen as they comprehensively dictate the water-related decisions and their implementation in Delhi at present. As the focus of our work is on the value base of DJB, these documents were of particular interest to us. Policy documents are easily accessed in India via government websites. All these documents were collected and collated from the official website of Delhi Jal Board, Government of NCT of Delhi [69, 78, and 79]. Content analysis (Putt & Springer, 1989; Singleton et al., 1988; Spector, 1992) was conducted on these three documents to comprehend the values that the content symbolizes either directly or indirectly.

A well-defined coding procedure was used by allotting color codes to distinct values, and the values reflecting from the content of the plans and policies were categorized according to those codes. This helped us frame the results. The idea was to analyze the content by reducing it to value categories so that we could lay out the respective values that DJB prioritized or disregarded.

We used deductive coding, and overlapping and conflicting values were handled appropriately by putting them in both the categories. The coding scheme covered the full range of relevant values, by drawing on established frameworks like Schwartz's Value Theory, the UN good governance principles, the OECD principles, and Allen Rogers' principles of “effective water governance” which emphasize similar attributes that should be reflected from water governance such as transparency, accountability, participatory, responsive, consensus oriented, following the rule of law, equity, inclusive, effective, and efficient, sustainable, coherent, and integrative.

Table 1 served as the coding manual that explicitly defined each water governance value for us. It gave us a clear definition of the value. The keywords or phrases that indicate the presence of the value in the text were identified on a subjective basis for laying down the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For instance, when coding for “sustainability,” the manual could specify that phrases related to “intergenerational equity,” “resource conservation,” and “long-term ecological balance” should be included, while statements focused solely on economic efficiency should be excluded.

We read the policy document carefully. Then, we identified sentences or paragraphs that expressed or implied water governance values. We then proceeded with comparing the identified text with the value definitions in Table 1 and assigned the appropriate value code to the text. If a text unit expressed multiple values, we coded for all relevant values.

The following excerpts from the DJB Act and the Delhi Water Policy explain how specific phrases were coded for particular values.

“The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy” emphasizes water conservation, which “fosters the values of sustainability and accommodation on the part of the DJB as it is adjusting its policies to the changing water availability.”

“The Delhi Water Policy endorses full cost recovery for water provisioning,” which shows the value of efficiency.

Expert interviews allow specific insights into processes and practices and so have an important role in uncovering what shapes policy formation and implementation (Beyers et al., 2014; Clarke & Braun, 2013; Dorussen et al., 2005; Patton, 2014; Van Audenhove, 2007). A variety of experts were interviewed, and this data was considered in conjunction with the policies. Experts were selected based on the importance of the position they held in development, implementation, or control of water policies, and local leaders who had privileged access to information about specific communities (Meuser & Nagel, 2009). Semi-structured interviews were then carried out with an inclination towards the subjective interpretations of the often-concealed beliefs and actual values that are not discussed more than often. These were asked directly or interpreted from the technical and process knowledge they shared along with their personal opinions or opinions of the government departments they worked for (Bogner et al., 2009).

Eleven semi-structured expert interviews were conducted between 2021 and 2023 with stakeholders including engineers of the DJB, academics from prominent institutions, city planners, local representatives, and other experts from the field to assess stakeholders' water values and how these shape policy and governance decisions. Each interview was tailored to the expertise of the individual to make the most of their specific knowledge, rather than following a general interview schedule. The interviews were transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed. These semi-structured interviews enabled us to uncover diverse perspectives on water values. Details of interviews are shared below in Table 2.

| Role/Title | Organization | Date of interview | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Former Commissioner | Delhi Development Authority (DDA7) | 09-08-2021 |

| 2. | Former Chief Town Planner | Town and Country Planning Organization (TCPO8) | 07-02-2022 |

| 3. | Executive Engineer | Delhi Jal Board (DJB) | 31-08-2021 |

| 4. | Water and Environmental Lead | National Institute of Urban Affairs, India (NIUA9) | 9-02-2022 |

| 5. | Environmental Planner-1 | National Institute of Urban Affairs, India (NIUA) | 9-02-2022 |

| 6. | Environmental Planner-2 | National Institute of Urban Affairs, India (NIUA) | 31-08-2021 |

| 7. | Professor | Department of Environmental Planning, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi (SPA-D10) | 31-08-2021 |

| 8. | Civil Engineer | Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IITD11) | 02-03-2022 |

| 9. | Economist | Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IITD) | 02-03-2022 |

| 10. | Researcher (Development Studies) | Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IITD) | 02-03-2022 |

| 11. | Ward Councilor, Chirag Dilli | Elected representative of the Chirag Dilli Ward12 | 18-07-2022 |

- Source: Author.

3 RESULTS

An overview of the values reflected in “The Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998”; “The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014”; and “Draft Delhi Water Policy, 2016” is presented in Table 3 below.

| Ethics and values | The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy | Score | Delhi Water Policy, 2016 | Score | The Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Values for Ethical Water Governance | ||||||

| Equity | Х | 1 | Х | 1 | Х | 1 |

| Solidarity | √ | 5 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Inclusivity & Empowerment | √ | 5 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Equality | √ | 5 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Human Dignity | √ | 5 | √ | 5 | Х | 1 |

| The Values for Sustainable Water Governance | ||||||

| The rights of nature | Х | 1 | √ | 5 | Х | 1 |

| The rights to nature | Х | 1 | √ | 5 | Х | 1 |

| Peacefulness | √ | 4 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Perseverance | Х | 2 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Accommodation | √ | 3 | √ | 5 | Х | 1 |

| Integration of societal systems | Х | 2 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Sustainability | √ | 3 | √ | 5 | Х | 1 |

| The Values for Effective Water Governance | ||||||

| Efficiency | Х | 1 | √ | 4 | √ | 4 |

| Commoditization | Х | 2 | Х | 1 | √ | 4 |

| Transparency | √ | 4 | √ | 4 | Х | 2 |

| Accountability | √ | 4 | √ | 4 | Х | 1 |

| Legalism | Х | 1 | √ | 4 | √ | 4 |

- Source: Author.

A scoring system of 1 to 5 was used, where: 1 = Value is completely absent or explicitly contradicted. 2 = Value is weakly present or mentioned in passing. 3 = Value is moderately present or implied in some Section 4 = Value is strongly present and influences several policy aspects. 5 = Value is a central organizing principle of the policy.

For Example, for “Sustainability”: 1: The policy promotes unsustainable practices, such as excessive water consumption, and disregards long-term ecological consequences. 2: The policy mentions sustainability in passing but lacks concrete measures or commitments to achieve it. 3: The policy includes some measures related to sustainability, such as water conservation, but these are not consistently applied or prioritized. 4: The policy strongly emphasizes sustainability, with clear goals and strategies for long-term resource management and ecological protection. 5: Sustainability is a central guiding principle of the policy, integrated into all aspects of water governance and decision-making.

We would like to emphasize the significant findings from our analysis that we consider are worthy of discussion.

First, The DJB Act, 1998 lacks emphasis on moral and sustainable governance values. It is inherently exclusionary and discriminatory, failing to address regulations for the sustainable use of water resources. The act supports the commoditization of water and legalism, leading to unequal access to water and sanitation services. A significant portion of residents, specifically two-thirds living in unauthorized colonies and slums, are clearly excluded from entitlements, being treated as non-citizens.

Second, the 20 Kiloliter Water Policy predominantly promotes inclusivity, accommodation, solidarity of government with the poor, accountability of government to the poor, human dignity, equality, and partially accomplishes sustainability. The value of equity, however, gets violated as each economic class is treated equally. Middle- and high-income households do not need water subsidies. Charging these classes on actual consumption would serve the purposes of fairness and justice and reduce water thefts by the middle classes and the rich. So, the free water policy could be amended to exclude the middle- and high-income groups from this policy. It is worth pointing out here that the DJB has already started work on this front by asking households to electronically opt out of this scheme if they wish to do so. Voluntary opting out needs to be replaced with compulsory exclusion by making amendments to the policy. On sustainability, a separate analysis needs to be conducted to find out how far this policy has contributed to water conservation. This policy has also reduced conflicts on the streets for fetching water from the tankers, thereby promoting the value of peacefulness.

Third, The Delhi Water Policy, 2016, encompasses the principles of ethical and sustainable water governance, with a strong emphasis on efficiency, sustainability, transparency, and the rights of nature. These values are crucial elements for ensuring water security in Delhi. In addition to that, the policy addresses all the necessary values for efficient water governance, except for commoditization.

Fourth, our examination of water policies concluded by revealing only faint indications of neoliberal3 ideology, particularly through the commoditization reflected in water tariff adjustments. However, the analysis of the values held by key stakeholders does not substantiate the notion that neoliberal principles or the primacy of economic values dominate Delhi's water management practices. In fact, recent policy guidelines emphasize that the primary objective for policymakers is the equitable and fair distribution of water. The insights gathered from various stakeholders—both on the supply and demand sides—indicate that the overarching goal of Delhi's water governance is to achieve ethical, sustainable, and simultaneously economically and technically viable outcomes. Consequently, no single set of values appears to dominate the framework.

Fifth, making the values explicit is largely disregarded in formulating water acts and policies of DJB, and values are never elucidated in the public domain.

3.1 Analysis of water policies and acts in Delhi

“The Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998” (The DJB Act, 1998); “The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014”; and “Draft Delhi Water Policy, 2016” (DDWP, 2016) are examined below through the lens of the water values. In doing so, we have undertaken a critical content analysis of the mentioned documents along with the available secondary literature in light of the interviews of experts, basically to elucidate the value analysis with empirical evidence. The three sets of values are not treated separately but are placed on a continuum starting from morality to sustainability to neoliberalism. Each set of values is discussed to create an analytical framework. Application of the framework forms the most important part of the paper, where water policies are examined through the lens of various values. We argue that without placing values at the heart of water governance, it is improbable to understand the nature and consequences of water policies for the citizens and nature. Specifically, we seek answers to some of the following critical questions: Do the act and policies promote fair and equitable distribution of water? Do they espouse the value of sustainability? Do they pay attention to the integration of societal systems? Do they aim for effective water governance?

We will start our analysis by illustrating what the identified sets of values mean in the context of water governance of a city by taking the example of Delhi and then analyze the act and policies by employing the values framework through a set of framed questions which we believe are critical to understanding the value sets that they propagate. We will address each question individually, deciphering the values behind the important provisions in these documents. An attempt is made to make the values guiding the decision-making processes explicit to identify the priorities of the stakeholders and the areas that can be worked on for better outcomes for all sections of the society, especially the poor and marginalized (Tables 4 and 5).

| Water values | Connotation for water governance in Delhi |

|---|---|

| The Values for Ethical Water Governance | |

| Equity | Equity should be maintained in per capita water distribution, access to water, and water use between different user groups without any discrimination while framing water and planning policies and their implementation. |

| Solidarity | Governments and water utilities should stand with the people and their needs when making water policies and statutes. |

| Inclusivity & empowerment | Considering water management as a technical issue, water policies are prepared by engineers, bureaucrats, and politicians without any involvement of common citizens. Interests of vulnerable citizens and opinions of stakeholders from diverse fields should be incorporated in water policies. This will enable the incorporation of diverse social, cultural, and economic standpoints of the society into policy framing and implementation. |

| Equality | Uniform spatial distribution of potable water should be prioritized. Here, emphasis is placed on the quantities of water supplied. |

| Human dignity | Access to water should be available at household levels to prevent low-income groups from relying on illegal private tankers selling water at the community level. This can prevent people from queuing and fighting for fetching water from the tankers in the NCT of Delhi. |

| The Values for Sustainable Water Governance | |

| The rights of nature | River Yamuna should be protected not only as a source of raw water to the city but as a living entity with the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles. |

| The rights to nature | Water, particularly river Yamuna is looked at as a resource benefiting the citizens of the city. Importance is accorded as per the social, economic, and cultural values assigned to it by humans. |

| Peacefulness | When supplying potable water, accessibility, affordability, and safety are foundationally considered important issues; resolution of these would promote peacefulness. |

| Perseverance | Policies and actions should be coherent. Policy makers should strive to address and solve the problems on the ground. |

| Accommodation | Adapting to changes in the availability of raw water and incorporating measures to address this issue in water policies. |

| Integration of societal systems | For example, in Delhi, there is a requirement of large quantities of water for the celebration of majority of the religious festivals, which needs to be integrated in policy-formulation. |

| Sustainability | Demand management, reducing pollution load in river Yamuna, mindful extraction of groundwater are some sustainable ways of using the available water resources. |

| The Values for Effective Water Governance | |

| Efficiency | Prudent use of water, conservation of water, and reuse of wastewater with the use of the minimum possible financial resources per unit of water produced. Water networks working effectively could result in reducing non-revenue water. |

| Commoditization | Water as a commodity subjected to market forces could exclude income poor people leading to water inequities. |

| Transparency | Transparency should be invoked at all four stages including policy framing, policy implementation, review, and evaluation. |

| Accountability | Participation of stakeholders, particularly citizens in the beginning of the policy formulation process makes the government accountable. People should be able to effectively influence public decisions and decision-making processes related to water. |

| Legalism | Legal frameworks should not be exclusionary. |

- Source: Author.

3.1.1 Brief overview of water policies and acts in Delhi

First, a concise summary of all the policies and acts is provided to establish the context and give an overview of the selected documents.

The Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998

The DJB Act was published on 2 April 1998 to layout the basic guidelines for the establishment of a water utility (DJB) with the responsibility of handling the functions of water supply, sewage disposal, sewerage, and drainage in the National Capital Territory of Delhi. The DJB Act of 1998 provides a broad outline of how the board would carry out its everyday functions and how to deal with all the major and minor conflicts that may arise within the board or between the board and the consumers or the government.

The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014

The water and sewer tariff structures are set by the DJB in consonance with the political aspirations of parties in power. Delhi government led by the Indian National Congress party periodically enhanced water tariffs during their 15 years of rule before reins were taken over by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP).4 The AAP came up with the free water policy in its election manifesto, which promised all citizens 20 kiloliters of free water per month per household, that is, 667 liters per household per day for domestic consumers having functional water meters. The policy was implemented with effect from January 1, 2014 onwards (Delhi Jal Board, 2014).

Water tariffs under this policy followed the principle of progressive pricing. It was the first time that an egalitarian water policy was implemented in the dominant neoliberal economic environment. If the citizens consume more than 20 kiloliters of water in a month, the household is billed as per the applicable tariffs for the full amount of water consumption. The water price rates per unit of volume increase as the used volume increases. Thus, the largest consumers of water pay higher rates for the volume of water consumed beyond a certain threshold (see Tables 3 and 5).

| Serial number | Monthly consumption (kiloliter) | Service charge (USD) | Volumetric charge per kiloliter (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 0–20 | 1.75 | 0.063 |

| 2. | 20–30 | 2.62 | 0.31 |

| 3. | Above 30 | 3.49 | 0.52 |

- Note: Additional sewer maintenance charge is 60 percent of the volumetric water charge.

- Source: Delhi Jal Board (2018).

Draft Delhi Water Policy, 2016

The AAP-controlled Delhi government's purpose behind getting a water policy formulated for Delhi was to ensure water security in Delhi. In fact, unreliable water resources and arbitrary amendments in the water policies in consonance with change of governing political party led to the need of a policy that could guide the decisions regarding the water sector and steer the city through the threats looming over its water security. The DJB outsourced the policy preparation task to the renowned NGO, the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).5

3.1.2 Values analysis on water policies and acts in Delhi

Water values may not be explicitly discussed in any of these documents, but values could be discerned from content analysis of the policy documents and legislations through the lens of the values framework as per the questions framed above. We will address these questions one by one for all the documents.

a. Tracing fair and equitable distribution of water

The DJB statute clearly mentions that the DJB is not liable to supply water to settlements that are constructed in contravention of any law, as stated under section 9 (1a) (Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, 1998). The act is exclusionary and discriminatory in nature as it does not promote universal access to water. The act is indifferent to the economic status of the low-income strata of the society as it places the responsibility of arranging for the end infrastructure on consumers as mentioned in sections 15a and 15b (Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, 1998). Even if the board provides for the same, it levies development charges to residents living even in unauthorized or regularized colonies, which makes it difficult for economically weaker sections to have equal rights to water supply.

The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014 hinges on the promotion of human dignity and protection of human rights by providing free water and sanitation services to diverse sections of society irrespective of their paying potential. But this comes with a condition of supplying water only to households receiving a piped water supply and having functional water meters. The households in jhuggi jhopdi clusters do not have meters, which keeps them dependent on informal ways of procuring water like community taps, illegal bore wells, and water tankers. This poses critical health risks and lays a huge economic burden on them. The number of functional water meters has increased from 857,000 m in 2015–16 to 1,883,000 in 2021–22 (Dialog and Development Commission of Delhi, 2022; Planning Department, 2022a). If Delhi's population increases to 20,000,000, we will get 4,000,000 households, which means the same number of households should have functional water meters. This crucially implies that 2,117,000 households remain unserved and cannot take advantage of the 20 free kiloliters water policy.

Moreover, half of the population falling within the coverage of this policy is the middle- and higher-income groups. The benefits of this policy are equally available to them, even when they are fully capable of paying for the quantity of water they consume. Hence, this policy fails to address the value of equity and fair and equitable distribution of water.

The Delhi Water Policy, 2016 mentions in its policy statements, Clause 15.4; Statement 8, that the residents will be ensured the minimum quantities of water required as per the set norms of water supply in the city at affordable prices. Both these policies propagate water as a human right following the interpretation of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and the UN resolution that India is a signatory to. The stress is on providing affordable water to all, irrespective of their income and social status. Thus, the policies advocate for the values of equality, solidarity, inclusivity, and empowerment quite vocally.

However, the experts do not endorse supplying water for free, rather they suggest cross subsidizing the tariffs.

b. Fostering sustainable water governance

i) Sustainable use of water resources

The DJB act lays down provisions for managing and regulating the exploitation of ground water as one of the main functions of the Board in section 9c (Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, 1998). However, DJB itself uses groundwater to supplement its water supply. It also sets forth measures for promoting conservation, recycling, and reuse of water under section 9 d (Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, 1998). The statute explicitly provides that water supplied for domestic purposes should not be used for any nondomestic purposes and prohibits all from willfully polluting water supplied for human consumption. However, it does not layout any measures directly for safeguarding the water resources from over-exploitation for the very purpose of water supply.

Considering the high dependence of Delhi on water procured from the neighboring states, supplying 20 kiloliter per month of free water might particularly motivate the low income-poor households to consume less water and hence lead to water conservation behavior. This emphasis of the 20 Kiloliter Water Policy on water conservation fosters the values of sustainability and accommodation on the part of the DJB as it is adjusting its policies to the changing water availability. Nevertheless, on the contrary, providing free water to all sections of society places a significant burden on natural water resources, both surface water and groundwater. The contradictory outcomes of the policy allow us to argue that the sustainable use of water resources has somewhat been disregarded in this policy. According to a recent report submitted to the National Green Tribunal, it was found that middle-income households are increasingly misusing this policy. The National Green Tribunal noted that many housing colonies were misusing the Delhi Government's scheme of free water by resorting to illegal groundwater extraction to avoid water threshold of 20,000 kiloliters and to avoid payment of water bills even after availing free water (Press Trust of India, 2019). Thus, the policy does not foster a sustainable water governance as a whole.

The Delhi Water Policy, 2016, places utmost importance on the sustainable use of water resources, both surface and groundwater. Efficient aquifer management is one of the policy statements that suggests augmentation of aquifers and enforcing regulation of groundwater extraction by enacting new legislations. The policy addresses the impending challenge of an inevitable increase in water demand in the near future and notes how the city is completely unprepared to tackle this situation. It points out the dependence of Delhi on neighboring states for raw water and over exploitation of groundwater sources. It also highlights the deteriorating condition of the river Yamuna, which is causing long-term damage to river ecological functions, leaving the riverine habitats unfit for many organisms and negatively affecting their water cleansing functions. At the same time, the policy provides possible solutions to deal with the identified issues, which can be a looming threat on the water security in Delhi. The policy also talks about the challenges of climate change and global warming. Augmentation of internal resources, such as wastewater reuse and building resilience to climate change, is one of the five pillars of the policy. These provisions in the policy provide the value base for sustainable water governance.

The Draft Delhi Water Policy, 2016 acknowledges the possibility of a potential conflict between the NCT of Delhi and the upper riparian cities as the city is completely dependent on their water resources for acquiring raw water as per MoU, 19946, which is up for review in 2025, if any of the basin states demand so. The upper riparian states objecting to the critical provisions of the MoU can result in an unresolvable conflict over water sharing. The policy makers uphold the value of peacefulness and suggest negotiating the terms of the MOU before the conflicts erupt.

Largely, DJB officers also uphold the values of accommodation, sustainability, and the rights of nature. All the experts that we interviewed advocated for the practice of active rainwater harvesting and recycling and reuse of wastewater for recharging groundwater and water bodies, and for potable and non-potable uses. They believe that demand management and mindful use of water are the key to achieving water security in Delhi and suggest strict and comprehensive policy enforcement. During an interview with the Executive Engineer of DJB conducted in August 2021, he suggested: Delhi is completely dependent on others for its water resources. If we go to Rajasthan (desert state), they collect all the rainwater. If you make storage tanks in your house, collect water, and then check its quality, you will see how clean it is. You can simply filter it and use it for drinking. It is distilled water. In Rajasthan, they place 5–6 buckets in rain to collect water. If you keep 2–3 buckets, they can be used in inverter batteries. Delhi does not have its water resources; it is completely dependent on other states.

ii) Integration of societal systems

Water holds a special place in the religious beliefs in India, where rivers are treated as goddesses. Immersion of idols in water bodies and taking holy dips are integral rituals of various religious festivals like Durga Puja and Chhath Puja in Delhi. DJB supplies an enormous amount of water for the immersion of idols in artificial ponds. These ponds are used for immersion mostly at neighborhood levels following the ban on immersion in river Yamuna in view of the prevention of any further pollution due to religious immersions. There are numerous other festivals throughout the year whose celebration involves a huge amount of treated water to be supplied by DJB. Despite the importance accorded to these celebrations, the DJB act or the 20 Kiloliter Water Policy does not lay down any provisions for supply of water at these times, hence leading to situation-based temporary solutions every year leading to chaos and water wastage. As per personal communication with the Executive Engineer of the DJB conducted on 31 August 2021: Delhi has more than 10,000 artificial ponds. Every colony has at least one pond. We supply treated tankers to fill up these ponds. On average 1,00,000 lts (100 kl) of water is supplied for one single pond. In colonies, the usual size for the pond is 10 m × 10 m × 2 m. This is the smallest size. Some of the ponds are so large that even after filling them up to a certain amount, they look empty. To fill them up to 3–4 ft, it takes 200 tanks of 10,000 lts of capacity, i.e., almost 20,000,00 lts of water.

On the other hand, Delhi Water Policy stresses the integration of societal systems as it recommends maintaining the minimum flow in water bodies, particularly that of river Yamuna for ecological and social needs. The social needs imply the availability of water for religious purposes like idol immersion, etc. It also directs the use of wastewater for non-potable purposes, as the social and cultural values associated with the use of water make people reluctant to use recycled water. Cultural values directly influence how water is perceived, delivered, and used for religious purposes (Mintz, 2018; Priscoli, 2012; Shaw & Francis, 2014). In this way, the policy tries to integrate societal values in decision-making so that the decisions are made pragmatically, which contributes to the conservation of water.

The policy stresses demand management to cope with the reduced per capita water availability over the years. Demand management is closely linked to one's beliefs, traditions and habits that influence everyday behavior regarding water i.e., the social values attributed to water (Finn & Jackson, 2011; Jackson, 2006; Wei et al., 2017). The policy mentions the need for change in mindset of the citizens of the country who consider high per capita water consumption as progress. Even the experts support demand management as a major contributor to ensuring sustainable water governance.

As per our values framework, integration of societal systems is vital for sustainable water governance and effective outcomes on the ground. Hence, we conclude that the Delhi Water Policy aims for a sustainable water governance as opposed to that of the other two documents.

c. Aiming for effective water governance

As per section 55 (2) of the DJB Act, the organization is required to recover all the operation and maintenance costs and repay debt by recovering water and sewerage charges from its consumers as per the quantities of water supplied. Additionally, a return of not less than three percent on net fixed assets is expected from DJB (Mathur, 2023). However, on the contrary, the act directs DJB to provide water to the New Delhi Municipal Council, the Delhi Cantonment Board, and the Military Engineering Services in bulk without any actual metering of the water used. The final issue rate is calculated by the total expenditure of the board in a year divided by number of thousand litres of water supplied by DJB in totality to itself and these areas. This provision is one of the reasons that DJB is not making enough revenue at the present and huge quantities of water are wasted. In an interview with Former Commissioner of the Delhi Development Authority conducted on 9 August 2021, he stated: “In areas like Lutyens's Delhi, the supply of water is almost three times of the supply to rest of the city. They are, in fact, wasting huge quantities of water for all sorts of non-potable uses such as washing their vehicles, washing their houses, and even horticulture and their personal kitchen gardens. So, this water use must be checked, and we need a differential pricing for water use.”

Moreover, the act does not lay down any provisions for an efficient water supply and wastewater treatment. As a result, the amount of unaccounted-for-water is substantial. Hence, the act does not effectively foster efficiency.

Delhi's domestic consumer water tariffs are one of the lowest when compared to several countries of the world. Providing water to at subsidized rates as per 20 Kiloliter Water Policy does not stand out as a feasible decision economically. As per interviews with experts including Former Chief Town Planner, TCPO, Water and Environmental Lead, NIUA, Former Commissioner, DDA, Environmental planners, NIUA, Executive Engineer, DJB, and Academic, SPAD, there should be a differential scale for pricing the affluent areas that have the capacity to pay. Most of them believe that water should be either be cross-subsidized. An academic interview on 11 August 2021 stressed: Providing water is a welcome thing. But what is important is at what cost it is being supplied. Water is quite costly; giving it for free is not a good practice. Water tariff structure is highly subsidized. This practice is not sustainable.

The Delhi Water Policy endorses full cost recovery for water provisioning. The policy lays emphasis on curtailing the distribution losses and enhancing the revenue recovered from water supply. Additionally, use of water-efficient devices, regulating phosphate content of detergents, use of waterless toilets, and performing water audits in line with energy audits for consumers of large quantities of water has also been recommended. The policy also suggests database management, changes in institutional organization like setting up of a Water Resources Commission, and promotion of innovations in the water sector. The value of efficiency is noticeably highlighted in the policy.

Holding workshops before placing the water policy in the public domain to get comments from various interested parties like concerned government and nongovernment agencies, civil society organizations, and resident welfare associations or RWAs (Delhi Jal Board, 2016) and outsourcing policy formulation to another organization reflects the value of transparency on the part of DJB.

d. Following the rule of law

Legalism, i.e., strict conformity to law is another value that appears to be followed by the DJB as it does not obligate the utility to provide water to informal developments, which is two thirds of urbanization in Delhi. Legalism hits the value of equity very hard in the case of 20 Kiloliter Water Policy, 2014.

The Delhi Water Policy, 2016 is compliant with the Constitution of India in allocation of powers and responsibilities of water sector in Delhi. It briefly explains the constitutional provisions and acts relevant to framing water policy in Delhi in Chapter VIII. The Constitution of India bestows the power of making laws regarding the subject matter of water on the state governments, which covers water supplies, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, water storage, and water power. Regulation and development of inter-state rivers and river valleys, and inter-state river disputes are under the control of central government. The policy suggests that the power of managing water should be assigned to both the center and the state. It advocates allocation of more powers to the state government for the regulation of groundwater, which can give DJB the complete power for the regulation, control, and development of groundwater and not only exploration and management of groundwater.

The policy upholds the Right to Water as per Article 21 of the Constitution of India. It emphasizes the proper implementation of the 74th Constitutional Amendment, 1993 empowers local governments and decentralizes urban governance to enhance citizens' participation in decision making and points out the significance of The MoU, 1994 between Delhi and upper riparian states.

4 DISCUSSION

We argue that if plans and policies are prepared to achieve desired outcomes backed up by values aspired by the society, and the values are made explicit at the start of the policy formulation process, we can achieve the desirable water governance outcomes (Van Ast et al., 2016). Policy and strategy documents often articulate these aspired values as principles (Jiménez et al., 2020). There are several distinct dimensions to what makes good water governance, and a focus on any element would likely overstate some values (Ingram, 2011). Thus, understanding the plurality of values behind policy formulation can remove the biasness towards the interests of influential stakeholders and help them to reflect what is desired by the communities (Schulz et al., 2017a). This will result in a better quality of life for the citizens and maximization of economic, social, and ecological benefits (Euzen & Morehouse, 2011; Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2006b).

This framework can make the public aware of the motivations behind policy framing processes. Awareness could potentially lead to peoples' participation, empowering the citizens and compelling the government to appropriately become accountable to the people. Moreover, having a better knowledge of values held by various stakeholders helps with conflict negotiation and resolution (Glenk & Fischer, 2010; Schulz et al., 2017b). We believe that a deeper understanding of beliefs and priorities of different actors and clearly laying out the preferred outcomes provides a clear picture of what each of the stakeholders is aiming at and what water governance path will be taken by them. This can help the stakeholders to reach a common page and work towards improving water governance outcomes.

Based on a three-pronged theoretical framework, this paper makes four theoretical contributions for future research. First, water governance is perceived as a set of social and political practices aimed at the distribution of water to the public for various purposes driven by forethought desired outcomes (unpacking). Second, the distribution of any resource including water must make the values held by the politicians, bureaucrats, and engineers clear. This framework helps make these values explicit to the citizens and gives them an idea about what to expect from the existing model of water governance. Third, water policies standing on a set of values clearly inform the residents about their future political choices. Four, having a better knowledge of values held by various stakeholders helps with conflict negotiation and resolution.

Assessing water governance from the perspectives of values and elucidating them in public domain encourages water policies and practices that prove to be citizen friendly and protective of nature in the long run by reducing disadvantages of decisions leading to pollution of raw water sources, misallocation and unequal access to water, wasteful use of fresh water sources, and reuse of used water. By bringing explicitness in values, governance of water utilities could better consider the future possibility of water scarcity, avoid wastages, and promote conservation of the limited resources of water, thus leading to sustainable water management. In this line of thinking, pricing of water must use market as well as nonmarket values to ensure efficacious, equitable, and affordable access to water (Euzen & Morehouse, 2011; Schulz et al., 2017b).

A deeper analysis of values is also necessary because water values show real motivations behind inclusion of certain important aspects of water policies. For example, upholding of water rights for the residents of Delhi is not the only intention of Delhi government for the implementation of the free 20 kiloliters policy; keeping intact a certain vote bank is another strong motivation. Against the common perception of fair and equitable distribution of water through this policy, when seen through the lens of values, it becomes quickly evident that the value of fairness is only partially achieved because a significant number of poor households remain without functional water meters and cannot benefit from free water scheme. Officers of DJB promote the value of equality but do not favor equity as water is provided free of cost to all. They equate free water supply to the poor as freebees, leading to water wastages preventing water conservation.

Further, understanding the interrelationships between water values and water governance can facilitate conflict resolution amongst different governance actors. Our analysis of water values is useful in figuring out what matters the most to a particular political regime. Further negotiations by local communities with the political regime could result in favorable policy outcomes for the residents. However, if deep differences in values are common, conflict resolution will become difficult (Schulz et al., 2017b). For instance, this has been illustrated through different responses by planners and engineers in our interviews. Planners believe in equity in the supply of water either by providing free water or by means of fixing a differential scale of pricing. They believe that blanket pricing leads to wasteful use of water, and certain segments of society that can afford to pay for water end up paying subsidized amounts. The DJB officers, on the contrary, believe that water should not be provided for free to any section of society.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, values are held to be intrinsic to any decision-making process, and urban water governance is no different. This paper outlines the relationship between values and water governance and proposes a theoretical values-framework. This values framework consists of three sets of values derived from the type of governance outcomes they help achieve. “The Values for Ethical Water Governance” include the values that aim for an “equitable, inclusive, and ethical water governance.” These values are equity, solidarity, inclusivity, empowerment, equality, and human dignity. “The Values for Sustainable Water Governance” aims for “sustainable water governance” and includes the rights of nature, the right to nature, peacefulness, perseverance, accommodation, and integration of societal systems. The third category includes the values of efficiency, commoditization, transparency, accountability, and legalism and aims at achieving an “efficient water governance” and are termed as “The Values for Effective Water Governance.” The novelty of this study is application of this framework on a decision-making context and understand the values that shape the governance of water, using Delhi as a case study. Application of values framework can clearly point out the values that can bring about transformative change in water governance and make key actors more accountable. Assessing water governance from the perspectives of values and elucidating them in public domain encourages water policies and practices that prove to be socially, economically, and ecologically viable in the long run. A deeper analysis of values is necessary also because water values show real motivations behind inclusion of certain important aspects of water policies and can facilitate conflict resolution amongst different governance actors.

In the case of Delhi, we were able to draw a picture of the values reflected from key acts and policies governing water. The DJB Act, 1998 lacks emphasis on moral and sustainable governance values. The act supports the commoditization of water and legalism, leading to unequal access to water and sanitation services. The 20 Kiloliter Water Policy predominantly promotes inclusivity, accommodation, solidarity of government with the poor, accountability of government to the poor, human dignity, equality, and partially accomplishes sustainability. The value of equity, however, gets violated as each economic class is treated equally. The Delhi Water Policy, 2016, encompasses the principles of ethical, sustainable, and effective water governance. It is clear from our study that values are not made explicit while designing water policies and acts, and these are never elucidated in the public domain in Delhi. As the values are never elucidated in public, we never know what exactly the policies and acts aim to achieve and what their goals are. If plans and policies are prepared aiming at achieving the desired outcomes based on values, Delhi can take a step towards being water secure with equitable access to all. Moreover, putting out the viewpoints and perceptions of the key water professionals of the DJB in the public domain will provide an opportunity to the academicians, planners, and most importantly local people, and the water utility itself, to initiate a dialog and come together to provide common solutions to the water problems faced by Delhi embedded in desired values.