Strain hardening of polymer glasses: Effect of entanglement density, temperature, and rate

Abstract

The strain hardening behavior of model polymer glasses is studied with simulations over a wide range of entanglement densities, temperatures, strain rates, and chain lengths. Entangled polymers deform affinely at scales larger than the entanglement length as assumed in entropic network models of strain hardening. The dependence of strain hardening on strain and entanglement density is also consistent with these models, but the temperature dependence has the opposite trend. The dependence on temperature, rate, and interaction strength can instead be understood as reflecting changes in the flow stress. Microscopic analysis of local rearrangements and the primitive paths between entanglements is used to test models of strain hardening. © 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J Polym Sci Part B: Polym Phys 44: 3487–3500, 2006

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical deformation of polymer glasses has been studied for many decades, and the basic features of the stress–strain curves are well known.1 At very small strains the response is elastic. At slightly larger strains, yielding occurs when intermolecular barriers to segmental rearrangements are overcome. Following yield, the material may exhibit strain softening, a reduction in stress to a level corresponding to plastic flow. At higher strains, the stress increases again as the chain molecules orient, in a process known as “strain hardening.” The balance of strain softening and strain hardening is critical in determining material properties such as toughness. Polymers that exhibit greater strain hardening, such as polycarbonate, are tougher and tend to undergo ductile rather than brittle deformation, because strain localization is suppressed.

(1)

(1)It is not clear why an entropic argument should apply in the glassy state where chains cannot move freely to sample the configurational entropy,4 but the network model of strain hardening has had much success in describing experimental results on polymer glasses. For example, Gaussian hardening has been observed in many uncrosslinked glasses.5, 6 More recently, van Melick et al. performed experiments7 that showed GR has the predicted linear dependence on ρe. However, in contrast with the entropic prediction, GR was not proportional to T but instead decreased linearly with increasing T. Also, GR was found7 to be about 100 times larger than ρekBT, even near the glass transition temperature Tg. The higher modulus can be attributed8 to “frictional forces” or to the greater energy necessary to plastically deform a material below Tg, but quantitatively little is known. Other open questions about glassy strain hardening remain as well, as summarized recently by Kramer.4

In this paper we examine the effect of entanglement density, temperature, chain length, and strain rate on the strain hardening behavior of model polymer glasses. Several previous simulation studies have considered strain hardening,9-14 but none have examined the factors controlling GR over a wide parameter space. This is desirable to understand the results of van Melick et al. and other recent experiments.7, 15, 16 To examine chemistry-independent factors controlling GR, we use a generic coarse-grained bead-spring model.17 The lower computational cost of this model allows us to simulate a wide variety of relatively large systems, allowing for good statistics and precise measurements of GR.

We find that the functional form of the stress–strain curves at fixed temperature and strain rate is consistent with entropic elasticity as defined by eq 1. Both Gaussian hardening and the more dramatic “Langevin” hardening2 are observed. Moreover, the transition between these two forms is consistent with rubber-elastic predictions.2 In addition, we reproduce the key result of van Melick et al., GR ∝ ρe, over a comparable range of entanglement densities.

Other simulation results reveal dramatic inconsistencies with the entropic network model. As in the experiments of van Melick et al.,7GR drops linearly with increasing T. This drop extends to the T → 0 limit, which is clearly inconsistent with eq 1. The ratio of GR to ρekBT is also comparable to experiment, remaining of order 100 even near Tg. Our results for the variation of GR with T, intermolecular interactions, and the rate of deformation can be understood if GR scales with the plastic flow stress σflow rather than a network entropy. Indeed entire stress–strain curves at different strain rates and interaction strengths collapse onto a universal curve when scaled by σflow.

It is known that GR decreases with decreasing molecular weight, and this has been attributed to greater relaxation of the entanglement network.15 We study the entire range of molecular weights from the N ≪ Ne to N ≫ Ne limits, with N the degree of polymerization. We find significant strain hardening even in unentangled systems. At small strains the chains deform affinely, and their increased length and alignment leads to strain hardening that is very similar to that of entangled chains. Only at large strains do the alignment and strain hardening begin to drop below those in entangled systems. The chain length dependence combined with the rate dependence discussed above suggests that strain hardening can be expressed as a product of the flow stress and a factor that represents the amount of local plastic deformation required to maintain connectivity of the chains.

Our simulations also allow us to examine microscopic quantities that are not easily accessible in experiments. Entangled chains deform affinely at large scales, as expected if entanglements act like crosslinks, and there is little entanglement loss through slippage at chain ends. The underlying entanglement structure is studied using primitive path analysis.18 A primitive path is the shortest path a chain fixed at its ends can take without crossing any other chains.19 The scaling of primitive path lengths with increasing strain is well described by a model assuming affine stretching of paths, and also by the nonaffine tube model of Rubinstein and Panyukov.20 The degree of plastic deformation is studied by examining the nonaffine component of deformation at low temperatures. Results for different entanglement densities fall on a universal curve for low strains, but increase more rapidly for higher entanglement densities at large strains. Strain hardening is related to microscopic plastic events, which are required to maintain chain connectivity. As the stress rises with increasing strain, both the number of events and the energy dissipated per event increase.

In the following section we describe the polymer model used in our simulations, and the protocols used to strain the system and identify primitive paths and entanglement lengths.18 Next we describe the effect of entanglement density, temperature, interaction strength, strain rate, and the microscopic rearrangements of monomers, chains, and primitive paths. The final section contains conclusions.

POLYMER MODEL AND METHODS

(2)

(2) .

. (3)

(3) (4)

(4)The values of N employed in this paper range from 4 to 3500, but most simulations have N = 350, which is long enough for the systems to be in the highly entangled (N > 8Ne) limit. The initial simulation cell is a cube of side length L0, which is chosen to be greater than the typical end–end distance of the chains. Nch chains are placed in the cell, with periodic boundary conditions applied in all three directions. Nch is chosen so that the total number of monomers Ntot = NNch is 30,000–280000, and typically 70000 (Table 1). The monomer number density is ρ = 0.85a−3.

| kbend | C∞ | N | Ntot | f | Ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 3.2 | 350 | 70,000 | 0 | 22 |

| 1.5 | 2.6 | 350 | 70,000 | 0 | 26 |

| 2.0 | 3.2 | 350 | 70,000 | 0.25 | 28 |

| 2.0 | 3.2 | 350 | 70,000 | 0.33 | 29 |

| 1.5 | 2.6 | 350 | 70,000 | 0.25 | 36 |

| 0.75 | 2.0 | 350 | 70,000 | 0 | 39 |

| 2.0 | 3.2 | 350 | 70,000 | 0.5 | 45 |

| 0 | 1.7 | 500 | 250,000 | 0 | 71 |

| 0.75 | 2.0 | 350 | 70,000 | 0.5 | 77 |

| 0 | 1.7 | 3500 | 280,000 | 0.5 | 165 |

- Values of the entanglement length Ne and chain stiffness constant C∞ are given as a function of kbend and the fraction f of monomers in short chains of five beads. The total number of monomers Ntot in the simulation, and length N of long chains are also given.

(5)

(5)After the chains are placed in the cell, we perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Newton's equations of motion are integrated with the velocity-Verlet method23 and timestep δt = 0.007τLJ − 0.012τLJ. The system is coupled to a heat bath at temperature T using a Langevin thermostat24 with damping rate 1.0/τLJ.

We equilibrate the systems thoroughly at T = 1.0u0/kB, which is well above the glass transition25 temperature Tg ≃ 0.35u0/kB. For short, poorly entangled chains, we use the “fast pushoff” method.21 The cutoff radius rc is set to 21/6a, as is standard in melt simulations.17 The chains are allowed to diffuse several times their end–end length before the system is considered equilibrated. For longer chains, the time required for diffusive equilibration is prohibitively large, so we use the double-bridging-MD hybrid algorithm.21 In addition to standard MD, Monte Carlo moves that alter the connectivity of chain subsections are periodically performed, allowing the chain configurations to relax far more rapidly.26 In some cases, to reduce the entanglement density, we cut a fraction f of the long chains into pieces with N = 5 after the initial equilibration. Additional MD equilibration is then performed until the newly created short chains have diffused several times their length.

Glassy states are obtained by performing a rapid temperature quench at a cooling rate of Ṫ = −2 × 10−3u0/kBτLJ. We increase rc to its final value and cool at constant density until the pressure is zero. The quench is then continued at zero pressure using a Nose-Hoover barostat.23 Unless noted, the final temperature is 0.2u0/kB, which is about 3/5 of Tg. This temperature is chosen because it is high enough to observe significant thermal relaxation and strain rate effects, but still well below Tg. The resulting glasses have density ρ ≃ 1.00a−3. We have checked that results from other quench protocols are consistent with the conclusions presented below.

To examine trends in GR with entanglement density, it is necessary to measure ρe = ρ/2Ne. Melt entanglement lengths have been obtained for undiluted18 systems and vary from about 70 for fully flexible chains (kbend = 0) to 20 for semiflexible chains with kbend = 2.0u0. Measurements have not been made for diluted systems. Also, although quenching a melt into a glass has little effect27 on Ne, we still measure ρe at the various temperatures employed. The changes in ρe upon cooling are primarily due to changes in ρ. Values of ρe are measured by performing primitive path analyses (PPA)18, 28 on systems with N ≫ Ne. We also apply PPA to deformed states to examine how the primitive paths evolve with increasing strain.

In PPA, all chain ends are fixed in space and several changes are made to the interaction potential. Intrachain excluded-volume interactions are deactivated, while interchain excluded-volume interactions are retained. Turning off intrachain interactions means that self-entanglements are not preserved, but their number is negligibly small for the systems considered here.29 The covalent bonds are strengthened by setting k = 100u0, and the bond lengths are capped at 1.2a to prevent chains from crossing one another.29 The FENE potential is linearized for r < 0.75a so the length minimization takes place at constant tension.28 For semiflexible chains, the bond-bending potential is deactivated by setting kbend = 0. For systems diluted with short chains, the short chains are removed. This is justifiable because the short chains' contour length is smaller than the tube diameter.

(6)

(6) 〉 is the average squared end–end distance. The primitive paths have Gaussian random walk statistics, with Ne monomers per Kuhn segment.18, 29 Results for different systems are summarized in Table 1.

〉 is the average squared end–end distance. The primitive paths have Gaussian random walk statistics, with Ne monomers per Kuhn segment.18, 29 Results for different systems are summarized in Table 1.Several atomistic simulation studies have covered various aspects of strain hardening, but most have been for tensile deformation.9-12 For fundamental studies of strain hardening, compressive rather than tensile deformation is preferred because it suppresses strain localization. This allows the stress to be measured in uniformly strained systems. Previous atomistic simulations of strain hardening in compression13, 14 used united-atom models of polyethylene, and focused on dihedral (trans/gauche) transition physics rather than quantitative measurement of GR.

A plurality of the experiments7, 15, 16, 30, 31 most relevant to the present study have employed uniaxial compression; we therefore do the same. The systems are compressed along one direction, z, while maintaining zero stresses along the transverse (x,y) directions.32 The rapidity of the quench minimizes strain softening, which in turn yields ductile, homogeneous deformation even at the lowest temperatures and highest strains considered here.

The uniaxial stretch λ is defined as Lz/L , where L

, where L is the cube side length at the end of the quench. Since we consider compression, λ is less than one. Compression is performed at constant true strain rate

is the cube side length at the end of the quench. Since we consider compression, λ is less than one. Compression is performed at constant true strain rate

, which is the favored protocol for strain hardening experiments.8 We use

, which is the favored protocol for strain hardening experiments.8 We use  of between −3.16 · 10−5/τLJ and −10−3/τLJ. These rates are significantly lower than those employed in some previous simulations.11, 12 The systems are compressed to true (logarithmic) strains up to εfinal = −1.5, corresponding to λfinal = exp(−1.5) ≃ 0.223.

of between −3.16 · 10−5/τLJ and −10−3/τLJ. These rates are significantly lower than those employed in some previous simulations.11, 12 The systems are compressed to true (logarithmic) strains up to εfinal = −1.5, corresponding to λfinal = exp(−1.5) ≃ 0.223.

RESULTS

Variation of Stress with Strain and Ne

(7)

(7) approaches the contour length Nel0. The “Langevin” hardening model includes the change in configurational entropy as the ratio

approaches the contour length Nel0. The “Langevin” hardening model includes the change in configurational entropy as the ratio  increases.33 For uniaxial compression at constant volume,

increases.33 For uniaxial compression at constant volume,

(8)

(8) for an affine strain.34 For small h the ratio of Langevin to Gaussian hardening is 1 + 3h2/5, and the Gaussian approximation is usually considered adequate2 for h < 1/3.

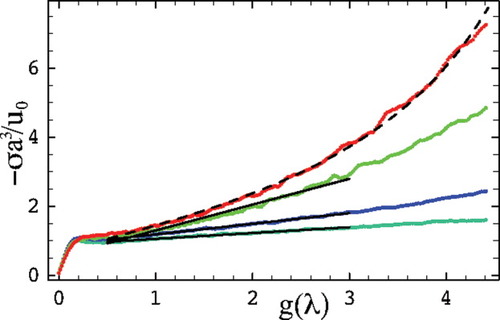

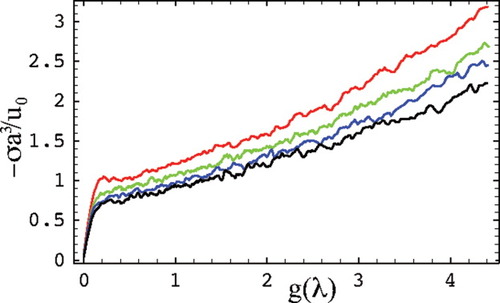

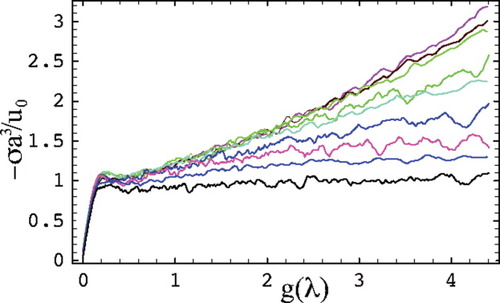

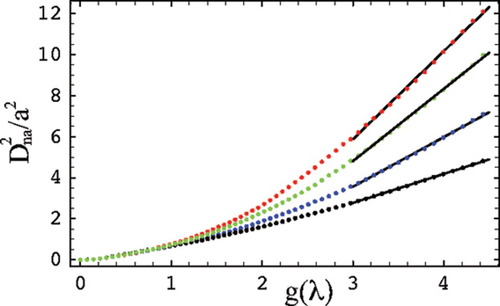

for an affine strain.34 For small h the ratio of Langevin to Gaussian hardening is 1 + 3h2/5, and the Gaussian approximation is usually considered adequate2 for h < 1/3.Figure 1 illustrates how the strain hardening varies with Ne in our simulations. The four cases shown span the range of Ne studied below. All simulations were done at

, and other parameters are listed in Table 1. As in many experiments,the stress is plotted against g(λ) so that Gaussian strain hardening corresponds to a straight line.

, and other parameters are listed in Table 1. As in many experiments,the stress is plotted against g(λ) so that Gaussian strain hardening corresponds to a straight line.

Strain hardening for various degrees of entanglement. The strain rate is

and T = 0.2u0/kB. Successive curves from bottom to top are for Ne = 165, Ne = 71, Ne = 26, and Ne = 22 and other parameters are provided in Table 1. Solid black lines indicate linear fits used to determine GR. A dashed curve shows a fit to eq 8, with the fit value of Ne = 14.25. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

and T = 0.2u0/kB. Successive curves from bottom to top are for Ne = 165, Ne = 71, Ne = 26, and Ne = 22 and other parameters are provided in Table 1. Solid black lines indicate linear fits used to determine GR. A dashed curve shows a fit to eq 8, with the fit value of Ne = 14.25. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

The behavior at small g is nearly independent of Ne. In this limit, g is proportional to strain. An initial elastic response is followed by yielding at a stress σy and nearly ideal plastic flow at a stress σflow. For the results shown in Figure 1, σy ≃ σflow, but postyield strain softening occurs at lower temperatures and slower quench rates.

The strain hardening at g > 0.5 depends strongly on Ne. For large Ne, the entire curve shows linear Gaussian strain-hardening. As Ne decreases, nonlinear Langevin strain-hardening sets in at smaller g. The nonlinearity becomes pronounced when h exceeds 1/3, as expected from the Langevin expression (eq 8). For Ne = 22, h = 0.4 in the unstrained state, and the results show pronounced curvature at all g. We find that such strongly nonlinear curves cannot be fit to the Langevin expression unless Ne is taken as a fitting parameter. The quality of such fits is illustrated by the dashed line in Figure 1. The fit value of Ne = 14.25 is about 2/3 of the value of Ne = 22 obtained from the PPA and plateau modulus.18

Experimental fits to Langevin strain hardening also produce smaller entanglement lengths than those determined from the plateau modulus.30, 35 This might be interpreted as a shift in the length between the effective crosslinks produced by entanglements, but may also reflect the limitations of the entropic network model. One is the assumption of constant volume. While volume changes less than 1% for the two systems that show Gaussian hardening, systems with Ne = 26 and 22 contracted by 3.2 and 5.5% respectively. Much of this contraction occurred at large g and could affect the fit to Langevin hardening.

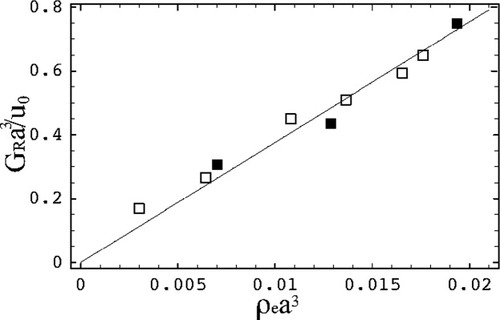

The network model also predicts that GR should increase linearly with entanglement density, and this prediction was verified in the recent experimental work of van Melick et al.7 Following their work, we obtain GR from linear fits to the stress over the range 0.5 ≤ g(λ) ≤ 3. Except for the most entangled system, Ne = 22, the behavior is nearly Gaussian over this range, and linear and Langevin fits to GR differ by less than 10%. Results for GR are plotted against ρe in Figure 2 over a slightly wider range (26 ≤ Ne ≤ 165) than considered in the experiments.7 As predicted by the network model, the results are well fit by a line passing through the origin. In the following sections we will consider whether GR/ρe scales with the temperature or the flow stress. The results in Figure 2 do not distinguish between these interpretations because T is constant and σflow only varies by ± 10%.

Plot showing proportionality of hardening modulus GR and entanglement density ρe. As shown in Figure 1, GR is obtained from linear fits for 0.5 ≤ g(λ) ≤ 3. Filled (empty) squares indicate the undiluted (diluted) systems from Table 1; the fractions f of short chains are indicated in this table. Error bars are of order the symbol size. Results for Ne = 22 are not shown since Langevin hardening extends to low strains, but Langevin fits to this and other Ne are consistent with the line drawn through the data.

Some authors have suggested that the Kuhn length lK, or more properly the chain stiffness constant C∞, plays a critical role in determining GR. They argue that the reason that GR is observed to be higher for polymers with larger C∞ is that straight chains are harder to deform.8, 9 However, these tests were performed on undiluted systems, in which C∞ and ρe cannot be varied independently. The data in Figure 2 show that systems of very different C∞ have similar GR if they are diluted so that they have the same entanglement density. We find that diluting gives an approximately linear decrease in both GR and the entanglement density from PPA. In particular, GR ≈ (1−f)G where G

where G is the undiluted value. Thus it appears that straighter chains have larger GR primarily because they are more densely entangled.

is the undiluted value. Thus it appears that straighter chains have larger GR primarily because they are more densely entangled.

To our knowledge, all previous simulation studies of strain hardening have employed dihedral (trans/gauche) interactions. Since dihedral interactions are absent from the model employed here, our results show that these interactions are not essential for strain hardening. Angular interactions apparently affect strain hardening only because they control the entanglement density through the equilibrium Kuhn length, and because of their less important effects on density and yield stress.

Effect of Temperature

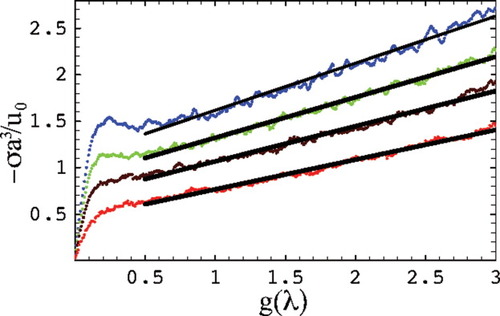

While both the form of the stress–strain curves shown in Figure 1 and the proportionality between GR and ρe are consistent with entropic elasticity, the temperature dependence is not. Figure 3 shows stress–strain curves for temperatures ranging from near zero to slightly below Tg. At higher temperatures, stress increases monotonically with strain, and exhibits a smooth transition to plastic flow. At low temperatures, the initial elastic response is followed by a clear peak and strain softening. In all cases, Gaussian hardening ensues at g(λ) ≃ 0.5. Again, values of GR are determined by linear fits to the stress over the range 0.5 ≤ g(λ) ≤ 3 and are reported in Table 2.

Strain hardening at kBT/u0 = = 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 from top to bottom. Simulations are done at strain rate −3.16·10−4/τLJ with Ne = 39, Nch = 200, and N = 350. Lines are fits to Gaussian hardening. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

| kBT/u0 | GRa3/u0 | ρea3 | GR/ρekBT | GR/σflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.0134 | 3800 | 0.35 |

| 0.1 | 0.44 | 0.0131 | 340 | 0.39 |

| 0.2 | 0.38 | 0.0129 | 150 | 0.41 |

| 0.3 | 0.32 | 0.0125 | 85 | 0.51 |

-

Data are for Ne = 39 and

.

.

Our results for GR show a linear decrease over the entire range of T from 0 to ∼Tg. A linear decrease was also seen in van Melick et al.'s experiments7 on increasing T from about 0.6Tg to 0.9Tg. The main difference from our observations is that a greater fractional change in GR was observed in experiments.7, 15, 30 This is due to the high strain rate employed in our simulations. The yield stress and GR only vanish at Tg in the low strain rate limit. Previous studies in similar systems show that σy drops linearly with temperature at all shear rates.25 At the strain rate used here, σy only decreases by about a factor of two as T changes from 0 to Tg. As the strain rate is decreased, σy goes to zero at Tg and the fractional change with temperature diverges. The relatively small change in GR with temperature in Table 2 is consistent with these observations, and rate dependence is discussed further below.

The decrease in GR with T in experiment7 and our simulations is inconsistent with entropic network models derived from eq 1. In the simplest form these predict GR = ρekBT. Experimental and simulation values for both GR and GR/ρe (Table 2) decrease linearly with increasing T rather than rising linearly. It has been suggested30, 34, 36-38 that a drop in effective entanglement density with increasing T could explain a decrease in GR near Tg. However, in order for a network model to explain the observed monotonic drop in GR from T = 0, the entropy would have to diverge faster than 1/T as T → 0, an unlikely proposition. Another difficulty with the network model is that even near Tg the values of GR are much larger than ρekBT. We find GR/ρekBT is of order 100 for T = 0.2 and T = 0.3, which is similar to the experimental ratios7 in the same range of T/Tg.

Refs.15,16 argue that thermally assisted relaxation of the entanglement network is the primary source of the drop in GR with increasing T. Primitive path analysis does not support this hypothesis. The stretching of primitive paths with strain, Lpp(λ)/L , is the same for T = 0.3u0/kB as it is for T = 0.01u0/kB (∼1.47 at ε = −1.5). Also, measurements of the nonaffine displacement of atoms as a function of chemical distance from the chain ends indicate that chain end slippage does not occur. Therefore, entanglement loss is negligible, at least at the large strain rate (

, is the same for T = 0.3u0/kB as it is for T = 0.01u0/kB (∼1.47 at ε = −1.5). Also, measurements of the nonaffine displacement of atoms as a function of chemical distance from the chain ends indicate that chain end slippage does not occur. Therefore, entanglement loss is negligible, at least at the large strain rate (

) used in these simulations. Instead, it seems that thermally assisted rearrangement at scales below the entanglement mesh is the primary source of the drop in GR with increasing T.

) used in these simulations. Instead, it seems that thermally assisted rearrangement at scales below the entanglement mesh is the primary source of the drop in GR with increasing T.

Local rearrangements are required to maintain chain connectivity during deformation of the glass. The local stresses required for these rearrangements must be of order of the flow stress. This decreases with increasing T due to thermal activation over local energy barriers (Fig. 3).25, 39, 40 The final column in Table 2 gives GR/σflow, with σflow measured at the onset of the strain hardening regime, g(λ) = 0.5. The ratio of hardening modulus to flow stress changes relatively little over the entire range of T, while GR/ρekBT changes dramatically. In the next section we examine the correlation between GR and σflow in more detail.

Scaling of GR with Flow Stress

The most direct way to vary the flow stress is by changing the intermolecular interactions. Changing the strength of the potential u0 will of course produce proportional increases in GR and σflow because all energies scale with u0. The flow stress also increases when the form of the potential is altered by increasing the cutoff rc, because a larger region contributes to the energy barriers preventing chains from sliding past each other. Table 3 shows that increasing rc produces comparable increases in both GR and σflow. Their ratio does not change within our numerical uncertainties as they increase by more than 50%. Note that the network model would not predict any change in the configurational entropy or GR with rc.

, N = 350, and Ne = 39

, N = 350, and Ne = 39| rc/a | GRa3/u0 | σflowa3/u0 | GR/σflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.92 | 0.41 |

| 1.8 | 0.45 | 0.97 | 0.46 |

| 2.2 | 0.56 | 1.25 | 0.45 |

| 2.6 | 0.60 | 1.44 | 0.42 |

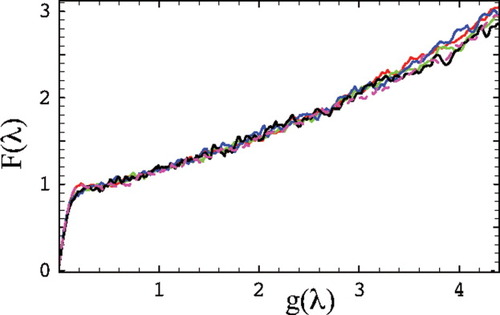

Studies of the strain-rate dependence of the stress also reveal a correlation between GR and σflow. Figure 4 shows stress–strain curves for an Ne = 39 system at four different strain rates ranging from −3.16·10−5/τLJ to −10−3/τLJ. The lowest three strain rates show a continuous transition between the elastic regime and plastic flow, while the highest rate shows a slight postyield strain-softening. At all strain rates Gaussian strain hardening is observed for 0.5 ≤ g(λ) ≲ 3. Both GR and σflow increase by about 35% with strain rate. The increase in GR is not accounted for in standard theories of strain hardening,30, 34, 36 where GR depends only on ρe and T. However, if GR scales with σflow, its rate dependence can be explained in terms of thermally activated local rearrangements.

Strain hardening at

, −10−4/τLJ, −3.16·10−4/τLJ, and −10−3/τLJ from bottom to top. Here kBT/u0 = 0.2 and Ne = 39.

, −10−4/τLJ, −3.16·10−4/τLJ, and −10−3/τLJ from bottom to top. Here kBT/u0 = 0.2 and Ne = 39.

(9)

(9) is a reference rate, b≡ kBT/V*, and V* is a constant with dimensions of volume. While studies25, 40, 43 show that b has a more complex dependence on temperature, the basic logarithmic dependence on rate is quite general. The variations in the flow stress observed in Figure 4 are consistent with these studies.

is a reference rate, b≡ kBT/V*, and V* is a constant with dimensions of volume. While studies25, 40, 43 show that b has a more complex dependence on temperature, the basic logarithmic dependence on rate is quite general. The variations in the flow stress observed in Figure 4 are consistent with these studies. (10)

(10) . The total change in σflow is a factor of two for the curves collapsed in Figure 5.

. The total change in σflow is a factor of two for the curves collapsed in Figure 5.

Ratio F(λ) of stress to flow stress for the data from Figure 4 with

(black), −10−4/τLJ (blue), −3.16·10−4/τLJ (green), and −10−3/τLJ (red) with rc = 1.5a. A dashed purple line shows the ratio of stress to flow stress for rc = 2.6a with

(black), −10−4/τLJ (blue), −3.16·10−4/τLJ (green), and −10−3/τLJ (red) with rc = 1.5a. A dashed purple line shows the ratio of stress to flow stress for rc = 2.6a with  .

.

We also examined the rate dependence of strain hardening for Ne = 22 where the hardening is highly nonlinear. The stress–strain curves at different rates also collapsed when scaled by the flow stress, but on a more nonlinear F(λ) because of the greater entanglement. Thus the correlation between strain hardening and the stress required for local rearrangements applies for both Gaussian and Langevin hardening regimes.

(11)

(11)Values of GR /σflow in Table 2 increase slightly with temperature, showing a bigger variation than the changes with rc and rate discussed in this section. This shows that thermally activated relaxation processes reduce σflow by more than they reduce GR. One possible explanation is that GR reflects the local rather than global flow stress, because local rearrangements must occur around each chain to maintain its connectivity during deformation. Studies of the global yield stress show that it decreases with increasing system size because there are more possible sites for fluctuations to nucleate yield.46 This effect should become more pronounced with increasing temperature, leading to a greater reduction of the large scale flow stress relative to the local flow stress. The rise in GR/σflow with increasing T in Table 2 would be reduced if GR was normalized by a larger local flow stress at higher T.

Chain Length Dependence

Our simulations allow us to test aspects of the microscopic picture underlying the network model. If the effective crosslinks come from entanglements, strain hardening should disappear for N < Ne and saturate for N ≫ Ne. In addition, the system should deform affinely at scales larger than

, something that is difficult to test in experiments.

, something that is difficult to test in experiments.

Figure 6 shows stress–strain curves for undiluted systems with Ne = 39 and chain lengths between 4 and 350. The initial elastic response and yield is fairly independent of N, although for large N the yield stress is slightly larger and there is some strain softening. For the N = 4 system, yield is followed by perfect-plastic flow, with no strain hardening. All other systems show strain hardening that increases monotonically with N. As expected from the network model, the stress appears to saturate for N ≫ Ne, and simulations at N = 500 showed no further change. Note however that there is a surprisingly large amount of strain hardening even for chains much shorter than the entanglement length. For example, the data for N = 25 show linear Gaussian hardening over the entire range of g.

Variation of strain hardening with N for systems with Ne = 39 at kBT/u0 = 0.2 and

. From bottom to top, N = 4, 7, 10, 16, 25, 40, 70, 175 and 350. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

. From bottom to top, N = 4, 7, 10, 16, 25, 40, 70, 175 and 350. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

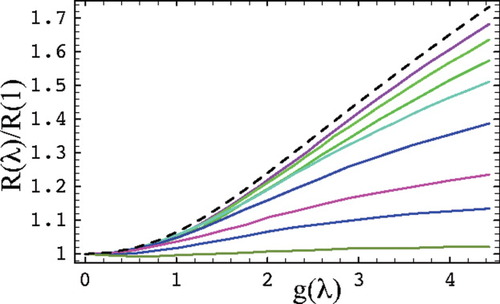

Strain hardening can occur as long as there is some order parameter that continues to evolve with increasing strain. We find a correlation between strain hardening and any measure of large scale chain orientation and deformation. A particularly simple one is the rms end to end length as a function of strain R(λ) normalized by its value in the initial state (λ = 1). Figure 7 plots R(λ)/R(1) for the systems whose stress–strain curves are depicted in Figure 6. A dashed line shows the prediction for an affine uniaxial deformation at constant volume,

, that is assumed to apply in the Langevin strain hardening model (eq 8).34 Results for highly entangled chains lie very close to this affine prediction, providing strong evidence that entanglements act like permanent crosslinks during deformation of these glassy systems. The small deviation (∼ 3% for N = 350) can be explained by noting that the entanglements will not be at the very ends of the chains and that the segments past the last entanglement need not deform affinely.* Note that neutron scattering experiments on deformed glasses also show that long chains deform nearly affinely on the scale of the radius of gyration, but short chains do not.47

, that is assumed to apply in the Langevin strain hardening model (eq 8).34 Results for highly entangled chains lie very close to this affine prediction, providing strong evidence that entanglements act like permanent crosslinks during deformation of these glassy systems. The small deviation (∼ 3% for N = 350) can be explained by noting that the entanglements will not be at the very ends of the chains and that the segments past the last entanglement need not deform affinely.* Note that neutron scattering experiments on deformed glasses also show that long chains deform nearly affinely on the scale of the radius of gyration, but short chains do not.47

Ratio of total rms length R(λ) to unstrained value R(1) as a function of g(λ) for N = 4, 7, 10, 16, 25, 40, 70, and 350 from bottom to top. A dashed line shows the predicted increase for an affine uniaxial compression at constant volume. Data for N = 175 lie on top of the N = 350 results and are not shown. Results are for Ne = 39 at

. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

There is a clear correlation between the degree of strain hardening (Fig. 6) and that of chain stretching (Fig. 7). The magnitude of the changes in both quantities increases monotonically with N and saturates above 5 to 10Ne. In this large N limit the chains deform affinely at large scales and their total length becomes irrelevant. Results for shorter chains follow the asymptotic large N behavior at small strains, and then cross over to a less rapid rise at a g that decreases with decreasing N. This suggests that the deformation involves straightening segments of increasing length as g increases. Only when this length becomes comparable to the chain length or Ne do the stress and R(λ) begin to saturate or follow the asymptotic behavior.

While chains of length 25 are only 60% of the entanglement length, they remain close to the asymptotic behavior up to g ≈ 2. Thus for this chain stiffness, entanglements only appear to affect strain hardening for g > 2. We expect that the degree of elongation in unentangled systems depends on a competition between the friction preventing relaxation of stretched configurations, and the decreasing number of configurations with a given degree of elongation. Thus the monomer friction, temperature, and strain rate may all affect the value of g where entanglements become important. For example, the higher shear rates used in the simulations of Lyulin et al.12 may have prevented nonaffine relaxation of short chains, explaining why GR was essentially the same for entangled and unentangled systems.

The very shortest chains in Figures 6 and 7, N ≤ 10, lie below the asymptotic curves at all g. The value of R(1) for these chains is already near the completely stretched limit Nl0 and they cannot align significantly under strain. For example, chains with N = 4 (about two Kuhn lengths) start at 80% of their fully extended length and show no strain hardening. For N = 7, R(1)/Nl0 = 0.6 and chains only stretch about 10% at the largest g studied.

A recent experimental result48 is consistent with our observation of strain hardening for chains with N < Ne. Wendlandt et al. found that the level of segmental orientation during plastic strain well below Tg is indicative of an effective constraint density much higher than the entanglement density in the melt. In addition to topological entanglements, they postulate the existence of frictional constraints, which cannot relax on the time scale of the experiment. Friction clearly prevents relaxation of the stretching in short chains in our simulations.

Plasticity and Nonaffine Displacements

(12)

(12) is the current position of a given monomer,

is the current position of a given monomer,  is its initial position at zero strain, and the average is taken over all monomers. To minimize the contributions to D

is its initial position at zero strain, and the average is taken over all monomers. To minimize the contributions to D from thermally activated diffusion, we present results for a very low temperature, kBT/u0 = 0.01. Previous studies have focused on deformation-enhanced mobility at higher temperatures.11-14

from thermally activated diffusion, we present results for a very low temperature, kBT/u0 = 0.01. Previous studies have focused on deformation-enhanced mobility at higher temperatures.11-14Figure 8 shows data for D plotted against g(λ) for four different entanglement densities. As noted above, we have also calculated D

plotted against g(λ) for four different entanglement densities. As noted above, we have also calculated D as a function of the position of atoms along highly entangled chains (N >5Ne). There is no statistically significant variation with position, indicating that chain end slippage does not play an important role.

as a function of the position of atoms along highly entangled chains (N >5Ne). There is no statistically significant variation with position, indicating that chain end slippage does not play an important role.

Nonaffine displacement D as a function of g(λ) = 1/λ − λ2. Successive curves from bottom to top are for Ne = 71, Ne = 39, Ne = 26, and Ne = 22. Solid lines indicate linear fits to the data for g(λ) ≥ 3. The system parameters are given in Table 1 and the strain rate is −3.16·10−4/τLJ. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

as a function of g(λ) = 1/λ − λ2. Successive curves from bottom to top are for Ne = 71, Ne = 39, Ne = 26, and Ne = 22. Solid lines indicate linear fits to the data for g(λ) ≥ 3. The system parameters are given in Table 1 and the strain rate is −3.16·10−4/τLJ. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

For strains up to g(λ) ≃ 1 (λ ≃ 0.7), the D data fall on a Ne-independent curve, showing that plastic deformation occurs on length scales below the scale of the entanglement mesh. At larger strains, well into the strain hardening regime, the rate of increase of D

data fall on a Ne-independent curve, showing that plastic deformation occurs on length scales below the scale of the entanglement mesh. At larger strains, well into the strain hardening regime, the rate of increase of D with g(λ) gradually increases, becoming linear in g(λ) at large strains. As in plots of stress and other quantities, the increase in the slope of D

with g(λ) gradually increases, becoming linear in g(λ) at large strains. As in plots of stress and other quantities, the increase in the slope of D occurs sooner for lower Ne.

occurs sooner for lower Ne.

Remarkably, the slopes of D at large strains (g(λ) ≥ 3) are proportional to ρe. Table 4 shows values of (∂ D

at large strains (g(λ) ≥ 3) are proportional to ρe. Table 4 shows values of (∂ D /∂ g(λ)) obtained from linear fits to D

/∂ g(λ)) obtained from linear fits to D for g(λ) ≥ 3. The fit lines are also shown in Figure 8. Values of Ne(∂ D

for g(λ) ≥ 3. The fit lines are also shown in Figure 8. Values of Ne(∂ D /∂ g(λ)) vary by only about 5%. This result is very surprising, especially since the more densely entangled samples are undergoing Langevin hardening at these strains while the hardening in the less entangled samples remains nearly Gaussian. The scaling of D

/∂ g(λ)) vary by only about 5%. This result is very surprising, especially since the more densely entangled samples are undergoing Langevin hardening at these strains while the hardening in the less entangled samples remains nearly Gaussian. The scaling of D with N

with N at large g suggests a simple picture in which the amount of plastic deformation is proportional to the density of entanglements.

at large g suggests a simple picture in which the amount of plastic deformation is proportional to the density of entanglements.

/∂g(λ)) versus ρe

/∂g(λ)) versus ρe| Ne | (∂D /∂g(λ)) /∂g(λ)) |

Ne(∂D /∂g(λ)) /∂g(λ)) |

|---|---|---|

| 71 | 1.41 | 100 |

| 39 | 2.42 | 94 |

| 26 | 3.52 | 92 |

| 22 | 4.29 | 94 |

-

Strain rate is

.

.

The increase in stress associated with strain hardening implies that more work must be done to produce each increment in strain. We observe a small increase in energy during deformation that is not expected from the network model, but is much smaller than the work performed. For the systems considered in Figure 8, the percentage of the work that goes into potential energy increases from 8 to 18%, with decreasing Ne. The entropic contribution to the change in free energy is also small, particularly, at the low temperature considered in this section. As a result, most of the work is dissipated as heat following local plastic rearrangements. The rate of work is proportional to the stress and should scale as the rate of plastic rearrangements times the energy dissipated in each.

One way of quantifying the rate of plasticity is to examine the nonaffine deformation δ D over a small strain interval δ ε = 0.025. Another is to count the number of atoms that undergo the large nonaffine displacements associated with plastic events. We find that the two measures are correlated because δ D

over a small strain interval δ ε = 0.025. Another is to count the number of atoms that undergo the large nonaffine displacements associated with plastic events. We find that the two measures are correlated because δ D is dominated by the atoms undergoing large displacements with typical size greater than 0.2a. Both show an increase in plastic deformation with increasing g. There is a rapid rise as the strain approaches the yield point, and then a slower rise in the strain hardening regime. Thus one factor in strain hardening is the increase in the amount of plastic deformation needed to maintain the connectivity of chains as g increases or the degree of entanglement increases. However, it appears that the stress rises more rapidly than the rate of plastic events at large g, particularly for Ne = 22. This implies that the energy dissipated in the events is increasing with g. Further studies of plastic deformation are underway.

is dominated by the atoms undergoing large displacements with typical size greater than 0.2a. Both show an increase in plastic deformation with increasing g. There is a rapid rise as the strain approaches the yield point, and then a slower rise in the strain hardening regime. Thus one factor in strain hardening is the increase in the amount of plastic deformation needed to maintain the connectivity of chains as g increases or the degree of entanglement increases. However, it appears that the stress rises more rapidly than the rate of plastic events at large g, particularly for Ne = 22. This implies that the energy dissipated in the events is increasing with g. Further studies of plastic deformation are underway.

Primitive Path Statistics

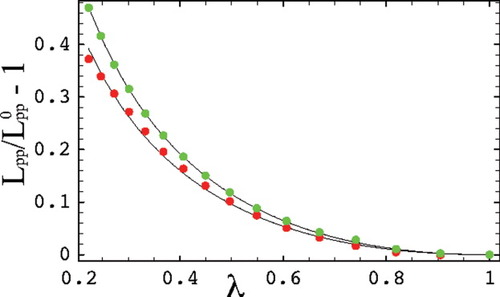

For the systems considered here, the deformation of chains is nearly perfectly affine on the end–end scale and there is negligible disentanglement through chain-end slipping. The network model of entanglements then suggests that the entanglement points and the primitive path between them will deform affinely. One way of testing this is to compare the increase in the contour length of the primitive path Lpp to the network model. Figure 9 shows Lpp(λ)/L − 1 for Ne = 22 and Ne = 39. We now show that these results can be described by two seemingly different models.

− 1 for Ne = 22 and Ne = 39. We now show that these results can be described by two seemingly different models.

Variation of Lpp(λ)/L −1 with λ for Ne = 22 (bottom) and Ne = 39 (top). Solid lines are fits to c(Y(λ) −1) with c = 0.58 and 0.70, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

−1 with λ for Ne = 22 (bottom) and Ne = 39 (top). Solid lines are fits to c(Y(λ) −1) with c = 0.58 and 0.70, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

(13)

(13) (λ)〉 and the strain-dependent tube diameter a(λ) by Lpp(λ) = 〈 R

(λ)〉 and the strain-dependent tube diameter a(λ) by Lpp(λ) = 〈 R (λ)〉 /a(λ). For volume-conserving compression the nonaffine tube model predicts

(λ)〉 /a(λ). For volume-conserving compression the nonaffine tube model predicts

(14)

(14) (λ)〉 = (λ2 + 2/λ)〈 R

(λ)〉 = (λ2 + 2/λ)〈 R 〉. Replacing 〈 R

〉. Replacing 〈 R 〉 with L

〉 with L a0, a0 drops out after some algebra, and the prediction is

a0, a0 drops out after some algebra, and the prediction is

(15)

(15)CONCLUSIONS

Simulations of strain hardening were carried out for glassy polymer systems with a wide range of entanglement densities. At fixed temperature and strain rate, the results are consistent with the entropic network model. The strain hardening modulus GR is linearly proportional to the entanglement density ρe and does not correlate with chain stiffness alone.8, 9 Both Gaussian and Langevin hardening are observed and the transition between them occurs at the expected entanglement density.

The effect of temperature on strain hardening is in dramatic disagreement with the entropic model. Both GR and GR/ρe decrease linearly with increasing T rather than being proportional to T. This behavior extends between the T → 0 and T → Tg limits. To accomodate this behavior, an entropic description would require that S diverge faster than 1/T as T → 0. In addition, values of GR at all temperatures considered were much larger than the entropic prediction GR = ρekBT. Near Tg the ratio GR/ρekBT is of order 100 in both our simulations and recent experiments.7 The decrease in GR with increasing T is similar to the corresponding decrease in the flow stress, suggesting that thermally assisted local rearrangements may reduce both quantities at higher temperatures.

The correlation between GR and the flow stress extended to variations with interaction parameters and rate. While both GR and σflow increase with the strength and range of adhesive interactions, the ratio GR/σflow remains essentially constant. Correlated increases with strain rate were also observed. Indeed the stress–strain curves for different rates and interactions collapsed onto a universal curve when normalized by σflow. The observed multiplicative dependence on strain and strain rate (eq 10) is very different than the additive dependence commonly assumed in constitutive laws (eq 11). The experimental literature offers conflicting results on the rate dependence of strain hardening. Some experiments6, 16, 39 show rate-dependent hardening, while others37, 50 do not. Most experiments are fit to additive constitutive laws like eq 11, but a multiplicative form like eq 10 has also been employed.41 In many cases the flow stress may not change by a large enough factor to distinguish between the two forms, but it would be interesting to test the multiplicative relation on a wider set of experimental data.

The effect of chain length on strain hardening was examined over the entire range of chain lengths from unentangled to fully entangled. Significant strain hardening was found in systems with chains much shorter than the topological entanglement length Ne. Hardening occurs as long as chains are able to continuously orient with increasing strain.

The evolution of microscopic quantities inaccessible to experiment was studied. The nonaffine part of the deformation was observed to fall on an Ne-independent curve at strains up to the early part of the strain hardening regime (g(λ) ≈ 1). This suggests that the deformation is restricted to chain segments shorter than Ne at small strains. The onset of a more rapid rise in the deformation moves to lower strains as Ne decreases and at high strains the rise in deformation is proportional to ρe. This is consistent with a simple model in which the amount of nonaffine (or plastic) deformation is proportional to the entanglement density. Studies of local plastic rearrangements indicate that strain hardening results from an increase in the amount of local plastic deformation with increasing strain and ρe, as well as an increase in the energy scale of rearrangements. Finally, the scaling of the increase in primitive path lengths was found to be consistent with both an affine primitive chain model and a nonaffine tube model, but the absolute values of the increases were smaller than those predicted.

We hope that the connections we have shown between GR and flow stress provide additional insight into the physics controlling GR. The flow stress is related to small scale structure and there is a growing understanding of the factors that control it.25, 40, 44, 46 The success of the network models in explaining the form of strain hardening suggests that entropic arguments may be able to predict the amount of deformation required to maintain chain connectivity, and thus the function F(λ) that multiplies σflow. Combining this approach with models for σflow may allow strain hardening to be predicted directly from knowledge of the microsopic interchain interactions.

Acknowledgements

Edward J. Kramer provided the inspiration for this work. Jorg Röttler and Kenneth S. Schweizer provided useful discussions. Gary S. Grest provided the DBH-equilibrated initial states. The simulations in this paper were carried out using the LAMMPS molecular dynamics software (http://www.cs.sandia.gov/∼sjplimp/lammps.html). This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants No. DMR-0454947 and PHY-99-07949.