Psychological predictors of adherence to lifestyle changes after bariatric surgery: A systematic review

Abstract

Objective

Adherence to lifestyle changes after bariatric surgery is associated with better health outcomes; however, research suggests that patients struggle to follow post-operative recommendations. This systematic review aimed to examine psychological factors associated with adherence after bariatric surgery.

Methods

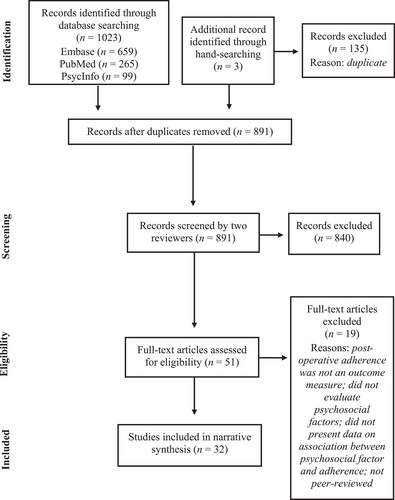

PubMed, PsycInfo, and Embase were searched (from earliest searchable to August 2022) to identify studies that reported on clinically modifiable psychological factors related to adherence after bariatric surgery. Retrieved abstracts (n = 891) were screened and coded by two raters.

Results

A total of 32 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the narrative synthesis. Appointment attendance and dietary recommendations were the most frequently studied post-operative instructions. Higher self-efficacy was consistently predictive of better post-operative adherence to diet and physical activity, while pre-operative depressive symptoms were commonly associated with poorer adherence to appointments, diet, and physical activity. Findings were less inconsistent for anxiety and other psychiatric conditions.

Conclusions

This systematic review identified that psychological factors such as mood disorders and patients' beliefs/attitudes are associated with adherence to lifestyle changes after bariatric surgery. These factors can be addressed with psychological interventions; therefore, they are important to consider in patient care after bariatric surgery. Future research should further examine psychological predictors of adherence with the aim of informing interventions to support recommended lifestyle changes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Bariatric surgery is among the most effective treatments for obesity, but there is also substantial variability in treatment outcomes.1, 2 Research suggests that this variability can be attributed, at least in part, to variability in adherence to post-operative lifestyle changes such as dietary changes, physical activity, and healthcare follow-up.3, 4 Despite strong evidence that post-operative adherence is associated with better weight loss, weight-loss maintenance, mental health, and quality of life,5, 6 patients often struggle to consistently enact recommended lifestyle changes. Therefore, it is important to improve the current understanding of the factors that predict post-operative adherence in the bariatric surgery setting.

Numerous reviews have examined psychological predictors of weight loss outcomes following bariatric surgery, which include (but are not limited to) depressive disorders, substance misuse, and disordered eating3, 6-8 but there has been less of focus on predictors of adherence to post-operative instructions regarding lifestyle changes. There are two existing systematic reviews of factors associated with post-operative adherence that focused on a range of demographic (e.g., age and unemployment) and clinical (e.g., pre-operative BMI) predictors.5, 9 While knowledge of these factors is valuable in identifying individuals at greater risk of poor post-operative adherence, they are not modifiable and, thus, can be of limited clinical utility. The review by Hood and colleagues included psychological factors5; however, this review contained studies published up until September 2015 and is therefore missing more updated findings.

In order to improve knowledge around factors that can be addressed in clinical practice, the present systematic review aimed to specifically examine clinically modifiable psychosocial predictors of adherence to common treatment instructions after bariatric surgery. For the purposes of this review, the term “psychological” is defined as factors pertaining to psychological wellbeing (e.g., mental health symptoms and disorders, emotional experiences) and cognition (e.g., self-efficacy, beliefs about adherence). This definition was kept broad in order to capture a wide range of factors that may be of clinical relevance.

2 METHOD

2.1 Search strategy

PubMed, PsycInfo, and Embase were searched to identify relevant articles from the earliest searchable paper through to August 2022 using keywords and MeSH terms related to two broad concepts: (1) bariatric surgery and (2) patient adherence or compliance. The search terms were based on the search strategies used in existing systematic reviews in the areas of bariatric surgery and treatment adherence, alongside discussions with a research librarian (see Supplementary File for the full search strategy). The search was kept broad in order to capture all studies that measured the relationship between a psychological factor and adherence. Additionally, the reference lists of included articles were hand-searched to identify relevant papers that were missed in the initial searches.

2.2 Study selection

A total of 1023 abstracts were located through the database searches and hand-searching (see Figure 1 for the flowchart of study selection). After removing duplicate results, 891 papers were independently screened by two raters (JC and a research assistant). Inclusion criteria were (1) included patient adherence to instructions after bariatric surgery as an outcome; (2) examined clinically modifiable psychological factors associated with post-operative adherence; (3) had an adult population (i.e., aged 18 years or older); and (4) written in English. Exclusion criteria were (1) did not have original data (e.g., reviews or editorial pieces); (2) examined only demographic, clinical, or surgical factors associated with adherence; (3) was a case study, trial, or qualitative study, which did not present data on the association between psychological variables and an adherence outcome; and (4) was not peer-reviewed. Studies were included only if they were considered relevant by both raters and any discrepancies were resolved by a third rater (LV). A total of 32 studies met inclusion criteria and were coded independently by two raters using a coding sheet developed for the purposes of this review.

Flow chart of study selection.

2.3 Data extraction

The following data were coded from the included papers: country where the study was conducted, demographic variables, surgical procedure, time since surgery, and study design. The raters also coded the post-operative recommendations(s) that were assessed with relation to adherence (e.g., diet, physical activity, follow-up appointment attendance, support group attendance, and vitamin/supplement use). The selection of these recommendations was guided by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Guidelines10 and discussions with bariatric clinicians. The psychological factors that were investigated as predictors of adherence in each study were coded as “positively associated”, “negatively associated”, or “not associated”. Although most papers also presented data on demographic and clinical factors associated with adherence, only data related to psychological predictors or correlates of adherence were extracted as these were the outcome measures for this review. In the case of missing data, attempts were made to contact the study's corresponding author via email for further information; however, not all authors responded. Where no response was received, missing data was indicated with “N/A”.

Study quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies.11 The measure comprises eight items designed to measure the potential risk of bias in study design, conduct, and data analysis. The items cover possible biases in participant recruitment, study sample, validity and reliability of measures used to define exposure, condition, and outcomes, identification/control of confounding factors, and appropriate choice of statistical analysis. The satisfaction of each criterion was rated as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable” by two independent raters (JC and LV). A study quality rating was given based on the number of criteria rated “yes”. Studies with low ratings were included in the review, but study quality was taken into consideration when synthesizing findings.

2.4 Data analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis was not conducted. A narrative synthesis method was used to summarize the direction of the relationship (positive, negative, or no significant association) between psychological factors measured in the studies and adherence to post-operative treatment instructions. Studies were grouped by post-operative recommendations.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study characteristics

Among the 32 included studies, the most commonly studied post-operative instruction was follow-up appointment attendance (n = 17), followed by dietary recommendations (n = 11), physical activity (n = 6), and support group attendance (n = 3). The studies included cross-sectional designs (n = 13), retrospective medical chart reviews (n = 10), prospective designs (n = 8), and a post-hoc analysis of randomized controlled trial data (n = 1). Psychological factors were assessed using self-report measures (n = 23), by health professionals (n = 8), or both (n = 1), and adherence was assessed via self-report (n = 14) and medical record data (n = 17). One study did not provide information on how adherence was measured. Most studies examined psychological factors pre-operatively (n = 20).

3.2 Study quality

The study quality ratings ranged from 3 to 8 (M = 6.34), with a maximum score of 8. All studies satisfied the criteria for adequate definition of inclusion criteria. The criterion that was least frequently satisfied was related to strategies to manage confounding factors, with only 50% of studies adequately controlling for confounds in their analyses. Table 1 shows the number of studies that satisfied each of the items in the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist, and the study quality ratings are included in Table 2.

| JBI critical appraisal checklist criterion | Studies satisfying criterion, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | 32 (100%) |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | 31 (97%) |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | 25 (78%) |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | 27 (84%) |

| Were confounding factors identified? | 19 (59%) |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | 16 (50%) |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | 22 (69%) |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 31 (97%) |

| Study (Year); Country | Bariatric procedure | Sample size | Sex (%F); Age (M, SD); Pre-operative BMI (M, SD) | Follow-up time/time since surgery | Study quality rating (0–8) | Study design | Measure of adherence | Measure of psychological predictor | Psychological predictors (Positive [Pos], Negative [Neg], Non-significant [NS]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative predictors | |||||||||

| Aarts et al. (2015); The Netherlands | Laparoscopic gastric bypass | 105 |

|

6, 12 m | 7 | Prospective survey study | Single item self-report of dietary adherence: “I generally/almost/did not follow dietary recommendations” |

|

|

| Barka et al. (2021); France | Sleeve gastrectomy; gastric bypass | 92 |

|

6, 12, 24, 36 m | 8 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance categorized into frequent attendees (attended at least two follow-up appointments in a 3-year period) and non-attendees (less than two appointments attended) | Medical records of pre-operative psychological evaluation of psychological and psychiatric history, previous psychiatric therapy, psychological impact of obesity; presence of negative emotions including altered body image, shame, shame facing others, and low self-esteem |

|

| Bergh et al. (2016); Norway | RYGB | 230 |

|

12 m | 7 | Prospective |

|

|

|

| Buddeberg-fischer et al. (2004); Switzerland | Gastric band; gastric bypass; gastric band then bypass | 119 |

|

M = 10 m | 5 | Prospective | Self-reported attendance at follow-up appointments | Psychosocial stress and symptom questionnaire, which comprised of the HADS, the binge scale questionnaire (BSQ), and the psychosocial assessment questionnaire (PAssQ) |

|

| Dixon et al. (2009); Australia | LAGB | 227 |

|

24 m | 8 | Prospective | Medical records of appointment attendance | Readiness to change: University of Rhode Island change assessment (URICA) scale |

|

| Gorin et al. (2009); USA | RYGB | 196 |

|

6 m | 6 | Prospective |

|

Medical records of pre-operative psychological evaluation of current and past history of psychiatric conditions. Evaluations were conducted by a clinical psychologist or psychiatric using a scripted interview based on DSM-IV criteria. |

|

| Hecht et al. (2022); USA | RYGB; sleeve gastrectomy | 210 |

|

12 m | 8 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance |

|

|

| Kedestig et al. (2019); Sweden | Laparoscopic gastric bypass | 2495 |

|

2 years | 7 | Post-hoc analysis of RCT | Study data on attendance at 2-year follow-up appointment | Medical record of pharmacological treatment for depression based on data reported to the scandinavian obesity surgery registry |

|

| Khorgami et al. (2015); USA | RYGB | 2658 |

|

1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 m | 5 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance | Medical records of pre-existing comorbidities |

|

| Larjani et al. (2016); Canada | RYGB; SG | 388 |

|

3, 6, 12, 24 m | 8 | Prospective | Study data on attendance to postoperative appointments | Assessment of psychiatric history and ongoing psychiatric comorbidities using the mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI), conducted by a psychiatrist or psychologist |

|

| Marek et al. (2015); USA | RYGB | 498 |

|

1 year | 8 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of attendance at 1-year post-operative appointment | Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-2-restructured form (MMPI-2-rf) |

|

| McVay et al. (2013); USA | RYGB | 538 |

|

3 w, 3, 6, 12 m | 8 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of 12-month follow-up appointment attendance |

|

|

| Ohta et al. (2022); Japan | LSG | 153 |

|

12 m | 8 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance | Medical records of psychiatric disorders evaluated by psychiatrists |

|

| Poole et al. (2005); UK | LAGB | 18 |

|

N/A | 5 | Retrospective chart review |

|

Review of psychiatric and surgical case notes for evidence of past or current disordered eating behavior, impulsivity, primary psychiatric diagnoses, and relevant attitudes/beliefs. |

|

| Sarwer et al. (2008); USA | RYGB | 200 |

|

20 w, 40 w, 66 w, 92 w | 6 | Prospective | Single-item self-report: “How well are you following the diet plan given to you by the dietitian?” on 9-point likert scale (1 - “not well at all” to 9 - “very well”) |

|

|

| Sockalingam et al. (2013); Canada | RYGB; SG | 132 |

|

12m | 8 | Prospective | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance |

|

|

| Toussi et al. (2009); USA | RYGB | 112 |

|

24m | 5 | Retrospective chart review |

|

|

|

| Vidal et al. (2014); Spain | RYGB; LSG | 263 |

|

N/A | 5 | Cross-sectional | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance | Medical records data, though it is unclear how depression was assessed |

|

| Wheeler et al. (2008); USA | RYGB; gastric banding | 375 |

|

90days | 8 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance |

|

|

| Won et al. (2014);USA | RYGB | 485 | 81%46.0 (11.0)47.8 (7.9) | 1year, 2years, 3years | 6 | Retrospective chart review | Medical records of follow-up appointment attendance |

|

|

| Post-operative predictors | |||||||||

| Adler et al. (2018); USA | RYGB | 274 |

|

M = 5.81 year | 4 | Cross-sectional | Single item self-report of dietary adherence: “How well are you following the diet plan given to you by the dietician/nutritionist/surgeon?” (scale from 1 to 9) | Six questions assessing frequency of maladaptive eating behaviors (scale from 1 to 7). Domains included: Grazing/mindless eating; eating foods “off the plan”; after-dinner hyperphagia; capitulating; loss of control |

|

| Carmichael et al. (2018); USA | Gastric bypass; gastric band; gastric sleeve; other | 320 |

|

M = 4.5 years | 3 | Cross-sectional | Self-reported adherence to follow-up appointments | Participant rating of relationship with primary surgeon and alternate surgeon/non-surgeon physician (scale from 1 to 5) |

|

| Feig et al. (2019); USA | Gastric bypass; sleeve gastrectomy; other | 95 |

|

M = 3.5 years | 7 | Cross-sectional |

|

|

|

| Feig et al. (2020); USA | Sleeve gastrectomy; gastric bypass | 112 |

|

M = 3.7 years | 7 | Cross-sectional |

|

|

|

| Hildebrandt et al. (1998); USA | RYGB | 102 |

|

M = 15.2 m | 3 | Cross-sectional | Self-reported number of support group sessions attended | Self-reported mood immediately after surgery and mood at time of study participation |

|

| Hochberg et al. (2015); Australia | LAGB | 179 |

|

N/A | 6 | Cross-sectional | Medical records of “surgical aftercare” session (i.e., follow-up appointment) attendance | Questionnaire developed for the purposes of the study, which included a list of 101 commonly perceived barriers to aftercare attendance. Patients rated endorsement of each barrier on a 5-point likert scale. |

|

| Hunt et al. (2009); USA | N/A | 212 |

|

M = 572days | 6 | Cross-sectional |

|

|

|

| Lester et al. (2014); USA | RYGB | 153 |

|

Range = 6–182m | 7 | Cross-sectional | The behavior scale, a 10-item measure using a 4-point likert scale, which was developed for the study to assess adherence to specific nutrition behaviors over the past month. |

|

|

| Miller et al. (2016); Australia | LAGB | 183 |

|

|

6 | Cross-sectional | Medical records of aftercare attendance | Gastric banding aftercare attendance questionnaire, a 31-item measure developed to assess barriers to aftercare attendance. Patients rated endorsement of each barrier on a 5-point likert scale. |

|

| Orth et al. (2008); USA | Gastric bypass; LAGB; VBG; revisional surgery | 46 |

|

N/A | 3 | Cross-sectional | N/A | The support group survey, a survey developed for the study to assess a patient's degree of agreeance with statements related to support group attendance. |

|

| Raves et al. (2016); USA | RYGB; VSG | 298 |

|

M = 20.8 m (12.3) | 8 | Cross-sectional |

|

|

|

| Zhu et al. (2022); China | Sleeve gastrectomy; gastric bypass; other | 288 |

|

3m–11year | 7 | Cross-sectional | Dietary adherence scale after bariatric surgery (DASBS) | Attitude-social influence-efficacy questionnaire after bariatric surgery (ASEQBS) |

|

- Abbreviations: LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band; RYGB, Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass.

The certainty in this body of evidence may be impacted by the presence of mixed findings for some treatment instructions (although, significant effects are generally in the same direction), the small number of studies available for some post-operative instructions, the variability in measures of adherence, and variability in study quality.

3.3 Psychological predictors of adherence

For appointment attendance, dietary adherence, and physical activity, the studies included in this systematic review were organized into subsections on (1) mental health symptoms and/or disorders and (2) beliefs/cognitions that were associated with adherence to post-operative instructions. These subsections were not used for the remaining outcomes (support group attendance, adherence to supplement use, and adherence to multiple instructions) because there were relatively few studies included.

3.4 Appointment attendance

3.4.1 Mental health factors

Studies investigating psychological factors related to adherence to medical and/or allied health follow-up appointments have focused primarily on emotional or mental health variables (see Table 2 for summary). In two studies of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy patients, having a history of any psychiatric condition was linked to poorer appointment attendance in the first 24–36 months after surgery.12, 13 Similarly, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) patients who had not attended any appointments in the previous 12 months were more likely than adherent patients to report that post-operative mental health problems acted as a barrier to attendance.14 However, other studies have failed to find the same association: specifically, pre-operative experience of “negative emotions”,12 pre-operative psychiatric diagnoses,15, 16 and psychiatric “stability” (i.e., having either no psychiatric history or well-managed symptoms)17 were not predictive of follow-up appointment attendance.

Specific mental health disorders have also been investigated in relation to appointment adherence. Pre-operative diagnosis of depression, high levels of depressive symptomology, and a history of pharmacological treatment of depression were predictive of missing follow-up appointments in the 24 months after gastric bypass surgery in three separate studies.13, 18, 19 However, four other studies found no link between pre-operative depression and adherence to follow-up appointments.20-23 In studies examining anxiety, higher levels of pre-operative phobic anxiety20 and an avoidant attachment style were associated with a lower likelihood of appointment attendance in the first 6–12 months post-surgery.21 However, there was no significant link between adherence and generalized anxiety15, 20 or an anxious attachment style21 in other studies.

Other behavioral and emotional disorders have also been examined in the context of post-operative adherence. Pre-operative behavioral problems (e.g., antisocial behaviors and substance use) were associated with poorer follow-up appointment attendance 1 year after surgery.24 In contrast, pre-operative emotional/internalizing dysfunction,24 hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, alexithymia,20 and maladaptive eating attitudes and habits23 were not significantly related to follow-up appointment adherence.

3.4.2 Cognitive factors

Patients' beliefs about adherence, about bariatric surgery itself, and about their surgeon have also been studied in relation to appointment attendance. Patients who reported low levels of motivation to attend follow-up appointments and/or to lose weight after surgery,14 and those who felt uncomfortable attending appointments,25 were more likely to have missed all follow-up appointments in the preceding 12 months than were patients who did not endorse those views. Conversely, patients were more likely to attend post-operative appointments if they reported a “good” or “very good” relationship with their bariatric surgeon compared with those reporting a “poor” or “very poor” relationship.26 However, adherence was not significantly correlated with readiness to change before surgery,27 nor with beliefs that adherence is too difficult, expectations concerning the outcomes of bariatric surgery, or perceived social/family support.14 Having limited health literacy and health numeracy has also been associated with a higher likelihood of missed and “no show” post-operative appointments, respectively.28

3.5 Dietary recommendations

3.5.1 Mental health factors

Mental health disorders or symptoms were among the most commonly evaluated psychological factors with regard to dietary adherence. Pre-operative positive affect, self-esteem, and body satisfaction were positively linked to dietary adherence. In a prospective study, those who had higher scores on self-report measures of positive affect and self-esteem also demonstrated greater improvements in their adherence to dietary recommendations from week 20 to week 92 post-surgery.29 Likewise, a prospective cohort study of 230 patients found that pre-operative self-esteem and body satisfaction were positively correlated with dietary adherence 1 year after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) surgery.30

In contrast, pre-operative depressive symptoms were negatively associated with dietary adherence in two prospective studies.29, 31 Patients who reported higher levels of depressive symptoms were more likely to identify as being “almost adherent” rather than “generally adherent” at 6 and 12 months after surgery, where the latter category was reflective of better adherence.31 Similarly, pre-operative negative affect predicted less improvement in patients' dietary adherence over time.29 Another study also demonstrated a negative correlation between pre-operative depressive symptoms and dietary adherence, but depressive symptoms were not a significant individual predictor of adherence in a regression model that also included pre-operative night-eating, readiness to limit food, and years of dieting experience.30

Depressive symptoms assessed after surgery also significantly predicted patients' classification as adherent (i.e., adhered approximately/more than half of the time) or non-adherent (i.e., adhered less than half of the time) to dietary recommendations.32 Other studies have found that having a history of mental health help-seeking,31 a history of sexual and/or physical abuse,13 and higher levels of pre- and post-operative generalized anxiety symptoms31, 32 were also negatively predictive of dietary adherence in the 6–24 months after RYGB surgery. Although attachment anxiety was similarly associated with poorer dietary adherence, attachment avoidance did not demonstrate a link to adherence.31 Contrary to the findings above, a separate study did not find a significant association between pre-operative generalized anxiety and dietary adherence.30

The literature has also identified eating disorders, disordered eating behaviors, and eating-related attitudes that are associated with dietary adherence. A history of purging,13 pre-operative emotional eating,33 pre-operative grazing (i.e., picking/nibbling),33 pre-operative night-eating,30 or a history of combined mood and eating disorder34 is predictive of poorer adherence to dietary recommendations in RYGB and gastric band patients. Poorer dietary adherence has also been associated with higher frequency of self-reported grazing, mindless eating, eating foods outside their dietary plan, after-dinner eating, “capitulating” (i.e., over-eating following perceived failure in dietary adherence), and loss of control after bariatric surgery.35 However, this was reported in a paper with a relatively low study quality rating (4/8). Conversely, patients who, prior to surgery, reported feeling more prepared to limit their food intake demonstrated better adherence after surgery, and those who reported having higher levels of eating-related cognitive restraint showed greater improvements in adherence over time.29, 30

3.5.2 Cognitive factors

Beyond these mental health factors, studies have also explored whether patients' cognitions about adherence are related to their dietary adherence behaviors. In a study of 153 female RYGB patients, both post-operative maintenance self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one's ability to adhere to treatment instructions) and post-operative relapse self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one's ability to get back on track after a lapse in adherence) were significant positive predictors of adherence.32 In the same study, patients who utilized action planning (i.e., planning details needed to adhere to recommendations) as a coping strategy reported higher levels of dietary adherence compared with those who used this strategy less frequently. However, no significant relationship was identified between coping planning (i.e., planning what to do in the face of barriers to adherence) and dietary adherence. Another study found that, post-operatively, a stronger intention to adhere, a more positive attitude toward adherence, and higher self-efficacy regarding adherence were associated with better dietary adherence.36

Finally, the role of internalized stigma has also been investigated with relation to dietary adherence. In a study of 298 patients who received RYGB or vertical sleeve gastrectomy within the 5 years prior to participation, those who had higher levels of internalized weight stigma were found to be at increased risk of engaging in disordered eating such as frequent snacking and perceived loss of control over food consumption.37 The internalized stigma was also negatively correlated with patients' self-assessed adherence to post-operative dietary recommendations. This finding was replicated in a separate study of 112 patients, in which weight bias internalization was associated with poorer self-reported dietary adherence (but not with adherence to fluid intake recommendations), even when controlling for age, gender, time since surgery, BMI, and surgery type.38 However, perceived weight stigma within healthcare settings specifically (e.g., weight-related discrimination from health professionals) was not associated with dietary adherence.37 Conversely, dietary adherence was positively associated with a stronger endorsement of social support or positive social norms related to dietary adherence.36

3.6 Physical activity

3.6.1 Mental health factors

Five studies evaluated the predictive value of mental health factors (including eating disorders) on patients' exercise adherence.13, 30, 34, 39, 40 Self-reported depressive symptoms before surgery were negatively predictive of physical activity in RYGB patients 12 months after surgery.30 Similarly, pre-operative psychosocial stress has been associated with poorer exercise adherence. A study of 119 LAGB and RYGB patients reported that those who were classified as experiencing “great psychosocial stress” (defined as meeting criteria for at least one of: depression, binge-eating disorder, or psychosocial problems in a self-report measure) were less likely to engage in regular exercise.39 However, this relationship was significant only in female participants.

In a study of RYGB patients, having a history of both mood and eating disorders was associated with a lower likelihood of exercising at least 5 days per week when compared with patients who reported no previous diagnoses, and compared to those who reported only a mood disorder or an eating disorder.34 That study did not report whether a statistically significant difference in adherence existed between those with just one psychological disorder and those with no disorders. Cross-sectionally, higher scores on measures of optimism and positive affect were associated with a higher frequency of engaging in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (but not with time spent walking) after bariatric surgery.40 However, this relationship was no longer significant once depression and anxiety were controlled for. Bergh and colleagues (2016) also assessed pre-operative night eating and binge eating in a cohort of RYGB patients and failed to find a significant relationship with physical activity levels 12 months after surgery. Surprisingly, in a separate study, having a history of sexual and/or physical abuse was correlated with better exercise adherence in the first 24 months after RYGB surgery.13 No significant relationships were found between exercise adherence and measures of pre-operative anxiety, emotion regulation, resilience, body satisfaction, self-esteem, or relationship satisfaction.30

3.6.2 Cognitive factors

In addition to psychological disorders or mental health factors, patients' beliefs have been linked to exercise adherence as well. This research has focused on beliefs that fall within the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which encompasses attitudes (i.e., beliefs about the benefits of the behavior), subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.41 The overall model of the TPB was significantly predictive of both intention to exercise and actual leisure-time physical activity (i.e., physical activity that is not related to work, transportation, or household chores) 6–9 months after surgery, and more than 12 months after surgery.42 Out of the three components of the TPB, post-operative perceived behavioral control (which is similar to self-efficacy) was the strongest and most consistent predictor of exercise adherence. A separate study also found a significant correlation between pre-operative self-efficacy and exercise adherence.30 Likewise, pre-operative planning for physical activity (e.g., what exercises to do, when to do them, and how to overcome barriers to exercise) was positively associated with exercise adherence. Conversely, weight bias internalization was negatively associated with time spent engaging in moderate-to-vigorous activity (but not time spent walking).38 Finally, views that patients reported before surgery, such as readiness to increase physical activity and expectations about wellbeing and social outcomes after surgery, were not significant predictors of exercise adherence.30

3.7 Support group attendance

Predictors of adherence to support groups or behavioral health groups (more akin to group therapy) were examined in three studies.20, 43, 44 One study examined the relationship between behavioral health group attendance and pre-operative depression, alexithymia, and psychiatric symptoms (i.e., hostility, anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity) in a group of RYBG patients.20 The behavioral health group utilized a cognitive-behavioral approach to address issues related to post-operative psychosocial adjustment, social support, adherence, and mindful eating. That study found that patients who attended fewer than two out of four behavioral groups in the first 12 months after surgery were more likely to have higher levels of pre-operative hostility, generalized anxiety, and phobic anxiety compared to those who attended three to four groups.20 However, these differences were only significant in univariate analyses. When hostility, anxiety, and phobic anxiety were included as predictors alongside travel distance (i.e., between the bariatric clinic and patients' homes) in a multivariate logistical regression, the psychosocial variables were no longer significantly predictive of group attendance. Travel distance remained a significant predictor in the regression, which suggests that it may explain behavioral group attendance over and above psychosocial factors.

Another study of RYGB patients found that self-reported mood (both pre- and post-operative) as well as emotional or psychosocial problems (operationalized as psychiatric treatment-seeking and use of psychotropic medications after surgery) were not significantly associated with support group attendance.43 In the third study,44 researchers investigated the views of patients who underwent bariatric surgery regarding in-person support group meetings. These views included patients' beliefs about the usefulness, necessity (for weight loss), and helpfulness of support group attendance. No significant differences in views were found between those who had never attended a post-operative support group and those who had attended at least one group, although non-attenders were marginally (p = 0.07) more likely than attenders to think that support groups would have no effect on weight loss and to think that support groups are not needed post-surgery. Note, however, that the latter two studies had relatively low ratings (3/8) on the measure of study quality.

3.8 Adherence to supplement use

Only one study presented data on adherence to vitamin supplements after bariatric surgery.38 In this cross-sectional survey study of 112 patients after sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass, greater weight bias internalization was associated with poorer adherence to recommended supplements.

3.9 Adherence to multiple instructions

Three studies measured adherence to a combination of post-operative instructions. In a small study of LAGB patients (N = 18), “non-compliers” (seven patients who were non-adherent to dietary recommendations and two patients who failed to attend any follow-up appointments for at least 12 months) were compared to nine control patients (randomly selected patients who had the same surgeon as the “non-compliers”).33 No differences between the groups were noted with regard to pre-operative binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, mood disorders, alcohol abuse, child sexual abuse history, insight about obesity, and the belief that the band is responsible for weight loss, but non-compliers were more likely to report pre-operative emotional eating. Another study examined the relationship between personality traits and affect and found that “overall adherence” (comprising diet, physical activity, fluid intake, and supplement use) was positively associated with post-operative positive affect and dispositional optimism.40 The third study examined adherence to vitamin use alongside other post-operative recommendations (e.g., dietary instructions, refusing to be weighed) under the category of ‘weight-loss instructions’,13 but no data were presented regarding psychological predictors of adherence to weight-loss instructions.

4 DISCUSSION

Pre-operative depression/depressive symptoms were commonly associated with poorer adherence to post-operative instructions, including dietary recommendations,29, 31 follow-up appointment attendance,13, 19 and exercise.30 Although six studies did not report a significant relationship between adherence and mood disorders/depressive symptoms, no studies identified a positive correlation between low mood and adherence. There was no discernible pattern of differences between the studies that identified a negative relationship compared to those that did not find a significant relationship in terms of study design, measures used to assess mood, and treatment instruction. Thus, pre-operative depressive symptoms appear to be a relatively consistent predictor of poorer adherence after bariatric surgery.

Likewise, pre-operative disordered eating behaviors and attitudes were consistently associated with poorer post-operative dietary adherence. This highlights the need to thoroughly assess for and treat maladaptive eating habits before surgery, particularly as patients may believe, prior to surgery, that their surgery would extinguish unhelpful eating behaviors.45 Therefore, patients should be offered education to manage expectations and support to address disordered eating behaviors before and after surgery. Studies have demonstrated that short-term psychological interventions such as motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy are effective in improving disordered eating behaviors in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.46-48

The results for anxiety in its various forms were less clear. Generalized anxiety,31, 32 phobic anxiety,20 and attachment anxiety31 were identified as barriers to adherence in some studies, but other studies did not find a significant association between generalized anxiety and post-operative adherence.15, 20, 30 This variability did not appear to be related to the method used to assess anxiety. Research on the anxiety/adherence relationship in other chronic conditions has similarly found weak associations.49 It may be that some forms of anxiety are associated with better or poorer post-operative adherence while other forms are unrelated, and identifying these relationships would be a worthwhile aim for future research.

When mental health factors were evaluated, it was common for studies to assess pre-operative symptoms or diagnoses as opposed to post-operative levels of these variables. Knowledge that pre-operative depression, for example, predicts post-operative adherence is undoubtedly useful as it allows the identification of individuals at increased risk of poor adherence. Where appropriate, clinicians could recommend psychological or pharmacological treatments for depression as part of patients' preparation for bariatric surgery to mitigate the risk of suboptimal outcomes. It is equally informative, however, to know whether post-operative depression similarly impairs adherence. Only one study measured post-operative depression (using the Patient Health Questionnaire50), finding that it was associated with a greater likelihood of being mostly non-adherent to post-operative dietary instructions.32 This may suggest that there is a need for clinicians to monitor and manage depression post-operatively to increase adherence and optimize treatment outcomes.

Another important factor to evaluate post-operatively may be cognitions (i.e., thoughts/beliefs) related to adherence, which was examined in only a few studies. Perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy after surgery were identified as facilitators of post-operative adherence in patients who received bariatric surgery.30, 32, 36, 42 This finding is in line with studies examining adherence in other chronic conditions.51, 52 However, beliefs about the usefulness of support groups did not differ between patients who did and did not attend these groups,44 although that study classified as “adherent” patients who attended even a single support group and also had a relatively low score (3/8) on the study quality measure. Only two studies investigated the role of internalized weight stigma with consistent findings of a detrimental impact on adherence.37, 38 Additionally, in the one study that examined the role of health literacy in follow-up appointment attendance, poorer health literacy was associated with lower attendance.28 This is consistent with the literature showing that health literacy positively predicts treatment adherence in other acute and chronic medical conditions and that interventions to improve health literacy can increase adherence.53 Therefore, it seems likely that increased health literacy may be beneficial for improving adherence in patients pursuing bariatric surgery, though further research is needed. Given the evidence that cognitions and knowledge play a role in behavior change and adherence,54-56 there may be of benefit in routinely discussing patients' views about post-operative adherence in follow-up appointments and addressing cognitions that may affect adherence. Indeed, psychological interventions aimed at addressing unhelpful cognitions have yielded promising outcomes in patients after bariatric surgery.57

Post-operative predictors of adherence to support group attendance have not been well-researched, with only three studies identified by this review. No significant relationship was found between support group attendance and psychological factors such as pre-operative and post-operative mood, emotional/psychosocial problems, and patients' attitudes toward support groups. Although one study reported negative correlations between support group attendance and pre-operative hostility and anxiety, these relationships were no longer significant once travel distance was taken into consideration.20 With the increased availability and acceptability of videoconferencing options, clinics could overcome the barrier of travel distance by offering online support groups. The literature suggests that over 70% of bariatric patients are interested in remote interventions after surgery,58 that telehealth options increase attendance,59 and that these interventions are associated with improved eating behaviors and psychological wellbeing.46

There is also very little data on psychological predictors of adherence to vitamin/supplement use after surgery.38 Although vitamin use may not impact on weight-loss outcomes directly, there is evidence that patients are at an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery60 and, thus, research examining psychological predictors of vitamin adherence after bariatric surgery is clearly needed.

The main limitations of this systematic review are that there were few studies available for several of the post-operative instructions examined, the diversity in how psychological factors and adherence outcomes were assessed, and the variability in study quality ratings.

5 CONCLUSION

Post-operative adherence is important for patients to maximize health benefits after bariatric surgery.5, 6 However, some patients struggle to consistently follow instructions given by their healthcare team.13 The current systematic review identified that pre-operative depression and disordered eating behaviors are consistently associated with poorer adherence; therefore, it is important to screen for and treat these conditions prior to surgery. Future research should seek to more deeply understand the impact of post-operative psychological factors, such as depression, anxiety, and cognitions, on adherence, as this could guide psychological management after surgery. The findings of this review also highlight the role of patients' cognitions/beliefs after surgery, as self-efficacy was consistently associated with better adherence, whereas internalized stigma was associated with poorer adherence. These psychological factors are amenable to treatment and, thus, are key considerations in patient care after bariatric surgery. Moreover, patients report an awareness of the impact of psychological factors on their ability to follow post-operative instructions, and view psychological care as essential for treatment success.45 Therefore, where clinically appropriate, health professionals working with patients pursuing bariatric surgery should offer psychological interventions before and after surgery to build skills that may improve post-operative adherence and treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Ashley McCuaig-Walton, Kate Nicholls, Eliza Paterson, and Veronica Smith for their assistance with abstract screening and data extraction. This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.