Mental health diagnosis attenuates weight loss among older adults in a digital diabetes prevention program

Abstract

Objective

Diabetes Prevention Programs (DPP) are effective at reducing diabetes incidence via clinically significant weight loss. Co-morbid mental health condition(s) may reduce the effect of DPP administered in-person and telephonically but this has not been assessed for digital DPP. This report examines the moderating effect of mental health diagnosis on weight change among individuals who enrolled in digital DPP (enrollees) at 12 and 24 months.

Methods

Secondary analysis of prospective, electronic health record data from a study of digital DPP among adults (N = 3904) aged 65–75 with prediabetes (HbA1c 5.7%–6.4%) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Results

Mental health diagnosis only moderated the effect of digital DPP on weight change during the first 7 months (p = 0.003) and the effect attenuated at 12 and 24 months. Results were unchanged after adjusting for psychotropic medication use. Among those without a mental health diagnosis, digital DPP enrollees lost more weight than non-enrollees: −4.17 kg (95% CI, −5.22 to −3.13) at 12 months and −1.88 kg (95% CI, −3.00 to −0.76) at 24 months, whereas among individuals with a mental health diagnosis, there was no difference in weight loss between enrollees and non-enrollees at 12 and 24 months (−1.25 kg [95% CI, −2.77 to 0.26] and 0.02 kg [95% CI, −1.69–1.73], respectively).

Conclusions

Digital DPP appears less effective for weight loss among individuals with a mental health condition, similar to prior findings for in-person and telephonic modalities. Findings suggest a need for tailoring DPP to address mental health conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Obesity and mental health conditions are highly prevalent among U.S. adults and many individuals struggle with these conditions concomitantly.1, 2 Approximately 42% of U.S. adults can be classified as having obesity and the rate of mental health conditions, such as depression, is significantly higher among those with obesity compared to those without.3-5 Individuals with obesity are at increased risk for developing many comorbid conditions, including type 2 diabetes, and having a concurrent mental health condition amplifies this risk.6-10 The bidirectional relationship between depression and metabolic conditions—obesity and type 2 diabetes—has been established.11-15 Multiple factors contribute to the association and research indicates the role of health behaviors, such as physical inactivity and poor diet, in mediating the relationship, as well as physiological factors related to psychotropic medications.15

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) has been a central strategy in diabetes prevention efforts for the past decade and is effective at reducing diabetes incidence as a result of clinically significant weight loss.16, 17 Yet, studies of the effectiveness of DPP among individuals with common mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety, are limited. A study of in-person DPP among veterans found that those with prediabetes and a diagnosis of a serious mental illness lost significantly less weight at 6 months compared to those with prediabetes and no mental health condition; the trend continued through 12 months but was not significant.18 A study among Hispanic/Latino women who received in-person DPP found that participants whose mental health symptoms worsened over time experienced significantly lower mean weight loss at 12 months than those whose symptoms remained stable or improved.19 In a study of telephonically-delivered DPP, participants with depressive symptoms had both significantly lower mean weight loss at 6, 12 and 24 months than those without symptoms and were less likely to achieve clinically meaningful weight loss at all time points.20 Thus, despite methodological differences across previous studies, such as definition of mental health condition (diagnosed disorder or presence/intensity of symptoms), and specific population (veterans, Hispanic/Latino women, general), having a mental health condition appears to attenuate the effect of DPP on weight loss. However, previous studies have only examined this phenomenon for DPP delivered either in-person or telephonically.

Development and use of digital and online platforms to deliver DPP has increased considerably over the years.21 In addition to its proven effectiveness for weight loss,22-25 digital DPP has a broader reach than in-person and is considered more convenient by participants.26 Given that digital DPP has the potential to expand access to an evidence-based behavioral intervention, which has become even more imperative during the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems relevant to also examine the effectiveness of this delivery modality in the context of mental health. Therefore, this study examined the moderating effect of a mental health diagnosis on weight change over a 12 and 24-month period among older adults who were invited to participate in digital DPP.

2 METHODS

This was a secondary analysis using data from a natural experiment study examining weight and hemoglobin A1C change among older adults with obesity and prediabetes who were invited to participate in a 12-month digital DPP (R01DK115237).27, 28 The study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a large, integrated health care system that provides comprehensive prepaid healthcare to approximately 600,000 members in Oregon and southwest Washington. All data used in the analyses were collected as part of standard healthcare administration and recorded in the electronic health record (EHR) system used by KPNW (Epic®). This study was approved by the KPNW Institutional Review Board (Protocol # STUDY00000693).

2.1 Participants and recruitment

The protocol from the overall study has been published elsewhere.27 In summary, patients who were invited to participate in digital DPP were identified in early 2017 based on meeting the following inclusion criteria in the EHR: current KPNW health plan member; age 65–75; BMI ≥30 kg/m2; HbA1c 5.7%–6.4%; no prior diagnosis of diabetes; and had access to and was actively using the electronic patient portal (approximately 80% of all KPNW health plan members meet this criterion). Eligible patients were sent a secure email message via the patient portal that provided a unique web link to enroll in digital DPP at no cost to the patient.

2.2 Digital DPP intervention

Omada Health provided the digital DPP intervention to KPNW patients, using a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-recognized translation of the DPP lifestyle intervention. The 12-month program has been described previously and included a 16-week intensive program and a 36-week maintenance program that consists of (virtual) small group support, health coaching from CDC-trained lifestyle coaches, a National DPP approved curriculum, and electronic behavioral tracking tools.27, 29

2.3 Mental health diagnosis and psychotropic medication use

EHR data were used to identify mental health diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. Patients with at least one encounter with a diagnosis code of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder during the 12 months prior to being invited to participate in digital DPP were classified as having a mental health diagnosis (i.e., yes vs. no). This approach has been used in other studies within integrated health care organizations, such as the Veterans Health Administration, where all behavioral and medical health services are delivered within one system, as it is at KPNW.5, 18, 30 Psychotropic medication use was identified from pharmacy prescription fill data during the 24-month follow-up period. Patients with at least one pharmacy dispense of a psychotropic medication during the study time period were classified as using psychotropic medications (yes vs. no; with always “yes” after the first dispense of the medication), which was treated as a time-varying variable.

2.4 Outcomes

The primary outcome was weight change over 12 months; the secondary outcome was weight change over 24 months. Weights recorded in the EHR as part of standard clinical care from April 2016 (up to 12 months prior to April 2017 when patients were invited to participate in digital DPP) to April 2019 (up to 24 months after the invitation month) were extracted and used in the analyses. Over the full 24-month observation period, patients had a mean of 7.5 (SD = 6.3) weight measurements recorded in the EHR with a range of 1–37 weight measurements per patient.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The primary covariates of interest included time in months since baseline, digital DPP enrollment status (enrolled vs. not enrolled), and mental health diagnosis at baseline (yes vs. no). The following variables were identified a priori as confounders to adjust for in the model: age; race and ethnicity; sex; minutes of exercise per week; Charlson co-morbidity index score31; baseline tobacco use; education (census tract-level proportion completing high school or less); census tract-level median household income; estimated propensity score for enrolling in digital DPP28; baseline weight; and metformin use (yes vs. no; with always “yes” after the first dispense of the medication).

Weight trajectories over 24 months were modeled using a linear mixed effects model. Based on the distribution of the data and intervention duration, a piece-wise linear spline function with a knot at 7 and 12 months was used. Specifically, a scatter plot of the weight data exhibited a check-mark shape with the nadir at around 7 months. A second knot was applied at 12 months, when the intervention period ended, to observe weight trajectories in the 12 months after the intervention ended. To compare the time trend of weight trajectories between digital DPP enrollees and non-enrollees with and without a mental health diagnosis, models included a three-way interaction term between time since baseline, digital DPP enrollment status, and mental health diagnosis at baseline. Model assumptions were checked by examining residuals and predicted values cross-sectionally and over time. Marginal means (95% confidence intervals [CI]) and model-estimated weights averaged over all covariates in the model were estimated at baseline, 7, 12, and 24 months. The primary contrasts of interest were the differences in estimated weight change from time of invitation between digital DPP enrollees/non-enrollees, with/without a mental health diagnosis at 12 and 24 months. In a second model psychotropic medication use (yes vs. no) was tested as a time varying covariate given the potential effect of these medications on weight change. Lastly, the estimated percent change in weight between digital DPP enrollees and non-enrollees, with/without a mental health diagnosis at 12 and 24 months was assessed using the primary model.

Missing data was handled using full-information maximum likelihood. All analyses were evaluated using a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 and 95% CI and conducted using Stata/IC 15.1 (College Station) or SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc).

3 RESULTS

A total of 3904 patients were included in analyses—472 who enrolled in digital DPP and 3432 who did not enroll. The proportion of digital DPP enrollees and non-enrollees with a mental health diagnosis at baseline was similar: 24.8% of enrollees and 22.8% of non-enrollees (Table 1). In addition, there were no differences between patients by DPP enrollment status for psychotropic medication use (4.9% for enrollees and 6.5% for non-enrollees). Differences were observed between digital DPP enrollees and non-enrollees for certain characteristics—age, sex, prior tobacco use and select socio-economic factors, as presented in Table 1.

| Total | Not enrolled | Enrolled | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 3904 | 3432 | 472 | -- |

| Mental health diagnosisa, N (%) | 899 (23.0) | 782 (22.8) | 117 (24.8) | 0.33 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.2 (2.9) | 69.3 (2.9) | 68.7 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 2155 (55.2%) | 1865 (54.3%) | 290 (61.4%) | 0.004 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.07 | |||

| Black/African American | 41 (1.1%) | 32 (0.9%) | 9 (1.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 58 (1.5%) | 53 (1.5%) | 5 (1.1%) | |

| Otherb | 123 (3.2%) | 114 (3.3%) | 9 (1.9%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3682 (94.3%) | 3233 (94.2%) | 449 (95.1%) | |

| Weight in kilograms, mean (SD) | 100.5 (17.0) | 100.6 (17.0) | 99.6 (17.4) | 0.22 |

| Body Mass index, mean (SD) | 35.4 (5.1) | 35.4 (5.0) | 35.5 (5.2) | 0.58 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | 0.26 | |||

| 0 | 2328 (59.6%) | 2030 (59.1%) | 298 (63.1%) | |

| 1 | 858 (22.0%) | 756 (22.0%) | 102 (21.6%) | |

| 2 | 446 (11.4%) | 401 (11.7%) | 45 (9.5%) | |

| 3+ | 272 (7.0%) | 245 (7.1%) | 27 (5.7%) | |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 2131 (54.6%) | 1840 (53.6%) | 291 (61.7%) | |

| Former | 1605 (41.1%) | 1431 (41.7%) | 174 (36.9%) | |

| Current | 168 (4.3%) | 161 (4.7%) | 7 (1.5%) | |

| Proportion of neighborhood with high school degree or less, mean (SD) | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.31 (0.15) | <0.001 |

| Median neighborhood household income in thousands, mean (SD)_ | 63.3 (21.5) | 62.9 (21.3) | 66.9 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| Exercise minutes per week based on exercise as vital sign, n (%) | 0.06 | |||

| 0 min | 1895 (48.5) | 1693 (49.3) | 202 (42.8) | |

| 10–140 min | 825 (21.1) | 717 (20.9) | 108 (22.9) | |

| ≥150 min | 881 (22.6) | 758 (22.1) | 123 (26.1) | |

| Missing | 303 (7.8) | 264 (7.7) | 39 (8.3) | |

| Metformin use, n (%) | 87 (2.2) | 77 (2.2) | 10 (2.1) | 0.86 |

| Psychotropic medication use, n (%) | 245 (6.3) | 222 (6.5) | 23 (4.9) | 0.18 |

- a Mental health diagnosis included depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

- b Includes Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, and patients who endorsed “other.”

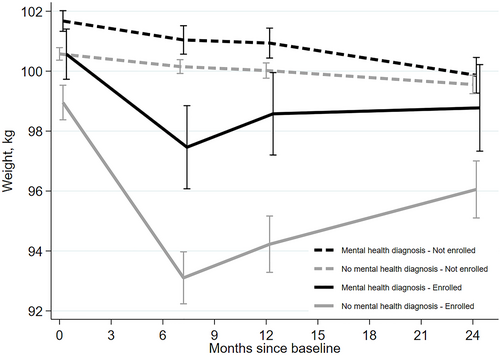

Figure 1 presents the estimated weight loss trajectories by digital DPP enrollment status and mental health diagnosis over 24 months. Overall, patients who enrolled in digital DPP, regardless of a mental health diagnosis, experienced the greatest weight loss, on average, in the first 7 months with some degree of weight gain thereafter; compared to those not enrolled, who experienced minimal to no weight change over time. Although there was no overall significant moderating effect of mental health diagnosis (i.e., mental health diagnosis*enrollment status) over the entire 24 months (p = 0.35), there was a significant three-way interaction (i.e., mental health diagnosis*enrollment status*time). Mental health diagnosis moderated the relationship between digital DPP enrollment status and weight change during the first 7 months (p = 0.003); however, this effect was not observed at 12 (p = 0.97) or 24 months (p = 0.25).

Estimated* (95% confidence intervals (CI)) weight trajectories by digital diabetes prevention programs (DPP) Enrollment and Mental Health Diagnosis Status. *Estimates (95% CIs) are marginal weights from a mixed effects model, with time since baseline modeled using a linear spline with a knot at 7 and 12 months. The model includes a random intercept and 3 random slopes (one for each time spline term); unstructured correlation structure was used for the random effects. The model was adjusted for age; race/ethnicity; sex; minutes of exercise per week; Charlson co-morbidity index score; baseline tobacco use; census tract-level proportion completing high school or less; census tract-level median household income; estimated propensity score for enrolling in digital DPP; baseline weight; and metformin use. The model included two-way interactions between each time spline with baseline weight, mental health diagnosis in the past year, and digital DPP enrollment status, and a three-way interaction of mental health diagnosis, digital DPP enrollment status, and time. All covariates were held constant at their means to estimate marginal weights by mental health diagnosis at the time points of baseline and 7, 12 and 24 months from baseline.

Among those without a mental health diagnosis, patients who enrolled in digital DPP lost 4.17 kg more (95% CI, −5.22 to −3.13) than non-enrollees at 12 months and 1.88 kg more at 24 months (95% CI, −3.00 to −0.76). Whereas among individuals with a mental health diagnosis, there was no significant difference in weight loss between digital DPP enrollees and non-enrollees at 12 and 24 months (−1.25 kg [95% CI, −2.77–0.26] and 0.02 kg [95% CI, −1.69–1.73], respectively). Among enrolled patients, those without a mental health diagnosis had significantly greater mean weight loss than those with a diagnosis at 12 months (−2.74 kg [95% CI, −4.47–−1.00]), but not at 24 months (−1.11 kg [95% CI, −3.02–0.80]). Results were unchanged after adjusting for psychotropic medication use. In terms of percent change in weight, among digital DPP enrollees, those with no mental health diagnosis reduced their initial weight by 4.7% (95% CI, −5.6% to −3.7%) over 12 months and 2.8% (95% CI, −3.8% to −1.7%) over the full 24 months. Enrollees with a mental health diagnosis lost 2.1% (95% CI, −3.6% to −0.6%) of their initial weight over 12 months and 1.7% (95% CI, −3.4%–0.0%) over 24 months [data not shown].

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this real-world implementation of digital DPP among older adults with obesity and prediabetes, having a mental health diagnosis significantly moderated the effect of digital DPP on weight change during the first 7 months only and the overall effect was not significant over 24 months. Yet, participants who enrolled in digital DPP with a mental health diagnosis experienced smaller weight loss at 12 and 24 months compared to participants who did not have a mental health diagnosis. These findings for digital DPP are generally consistent with previous studies that assessed DPP delivered in-person and telephonically. Specifically, Janney et al. evaluated in-person DPP among veterans with mental health conditions (based on ICD-10-CM codes) and found significant differences in weight loss at 6 months based on having a mental health condition; although the trend continued, it was not significant at 12 months18 Whereas the Trief et al. study of telephonic DPP, which assessed depressive symptoms over the duration of the intervention and follow-up period among their study population, observed significantly lower weight loss at 6, 12 and 24 months among those with elevated depressive symptoms.20 These findings together suggest that DPP (standard curriculum) is less effective among adults with a mental health condition, even across different delivery modalities (in-person, phone, digital).

Given that adults with a mental health condition(s) comprise a significant proportion of the overall U.S. population, have high rates of obesity, and experience disproportionate risk for prediabetes and development of type 2 diabetes, further refinement of DPP seems warranted to address this subpopulation's unique needs. Pilot studies that have tested DPP tailored for adults with a mental health condition(s) have had promising results related to its preliminary effectiveness for weight loss and feasibility of implementation.32-34 These studies suggest that utilizing peer support, breaking the DPP core content into additional sessions over a longer time period (vs. the standard 16 sessions delivered over 4–6 months), and more frequent contact both during the core curriculum (in-between sessions) as well as after the core curriculum (twice per month vs. once a month) may be needed to enhance the effectiveness of DPP among adults with a mental health condition.32-34 In addition, the literature assessing lifestyle interventions outside of DPP that target both depression and weight loss may offer important strategies for tailoring DPP that could simultaneously affect mental health as well as weight outcomes.35-39

This study has several limitations. First, EHR data were used for all variables and outcomes. Specifically, mental health diagnosis was identified by only using ICD-10-CM codes and not assessed using validated evaluation approaches, nor assessment of symptom severity. This may have contributed to an underestimate in the number of participants with a mental health condition as well as the effect on weight change. Furthermore, diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder were the conditions assessed as they are the most prevalent mental health conditions among the KPNW patient population. The primary outcome—weight change—also came from the EHR, which have established accuracy,40-43 but were not measured at set intervals related to intervention enrollment. Second, characteristics of the study population limit the generalizability of findings. The study population was primarily white, educated and limited to those 65–75 years of age. Lastly, although the model was adjusted for psychotropic medication use, only a small proportion of the study population were taking these medications and it was not feasible to assess medications associated with weight loss versus weight gain within this group, which may have contributed to the inability to detect an effect.

This study provides further evidence that there is a need for a DPP tailored to adults with a mental health condition. Given that the study sample consisted of older adults, findings also have potential policy implications since DPP is now reimbursed by Medicare. With the prevalence of social isolation, cognitive decline, and mental health conditions among older adults,44, 45 a tailored DPP for this vulnerable population may help reduce health care costs over time. Further research is needed to examine the potential behavioral and physiological mechanisms that may explain the interplay among prediabetes, mental health, and weight management.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analysis was performed by Ning Smith. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Meghan Mayhew and all authors commented on early versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (Project Number: 1R01DK115237).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.