Proposal for a Novel Classification of Patients With Enlarged Ventricles and Cognitive Impairment Based on Data-Driven Analysis of Neuroimaging Results in Patients With Psychiatric Disorders

Funding: This research was supported by AMED grants JP22tm0424222 (I.K.), JP21dk0307103 (Ry.H.), JP21uk1024002 (Ry.H., K.M., J.Ma., J.Mi.), JP21wm0425012 (Ry.H., K.M., J.Ma.), JP21wm0425007 (N.Oz.), JP21km0405216 (I.K.), JP19dm0207069 (K.M.), JP18dm0307002 (Y.O., Ry.H.); JSPS KAKENHI grants JP23H00395 (Ry.H.), JP23H02834 (K.K.), JP22H04926 (M.F.), JP21H05171 (K.K.), JP21H05174 (K.K.), JP21K07543 (I.K.), JP21H00194 (I.K.), JP21H02851 (Y.H.), JP20H03611 (Ry.H., K.M., J.Ma., NaomH), JP20K06920 (K.M., J.Ma., Naom.H.), JP20KK0193 (Y.H.), JP19H05467 (Ry.H.) JP18K07550 (T.T.), JP23K07001 (J.Ma.); JST Moonshot R&D Grant Number JPMJMS2021 (K.K.); 2019 SIRS Research Fund Award (Y.H.); UTokyo Institute for Diversity and Adaptation of Human Mind (UTIDAHM, K.K.); the International Research Center for Neurointelligence (WPI-IRCN) at The University of Tokyo Institutes for Advanced Study (UTIAS, K.K.); and Intramural Research Grant (3-1, 4-6) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP (Ry.H., K.M.). Some computations were performed at the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (projects: NIPS, 18-IMS-C162, 19-IMS-C181, 20-IMS-C162, 21-IMS-C179, 22-IMS-C195, M.F.). This work is supported by the NINS program of Promoting Research by Networking among Institutions (Grant Number 01412303, M.F.).

ABSTRACT

One of the challenges in diagnosing psychiatric disorders is that the results of biological and neuroscience research are not reflected in the diagnostic criteria. Thus, data-driven analyses incorporating biological and cross-disease perspectives, regardless of the diagnostic category, have recently been proposed. A data-driven clustering study based on subcortical volumes in 5604 subjects classified into four brain biotypes associated with cognitive/social functioning. Among the four brain biotypes identified in controls and patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and other psychiatric disorders, we further analyzed the brain biotype 1 subjects, those with an extremely small limbic region, for clinical utility. We found that the representative feature of brain biotype 1 is enlarged lateral ventricles. An enlarged ventricle, defined by an average z-score of left and right lateral ventricle volumes > 3, had a sensitivity of 99.1% and a specificity of 98.1% for discriminating brain biotype 1. However, the presence of an enlarged ventricle was not sufficient to classify patient subgroups, as 1% of the controls also had enlarged ventricles. Reclassification of patients with enlarged ventricles according to cognitive impairment resulted in a stratified subgroup that included patients with a high proportion of schizophrenia diagnoses, electroencephalography abnormalities, and rare pathological genetic copy number variations. Data-driven clustering analysis of neuroimaging data revealed subgroups with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment. This subgroup could be a new diagnostic candidate for psychiatric disorders. This concept and strategy may be useful for identifying biologically defined psychiatric disorders in the future.

1 Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) are the major psychiatric classification systems used worldwide. Both the DSM and the ICD define psychiatric disorders primarily by signs, symptoms, and disease course. However, signs and symptoms are nonspecific indicators shared by diagnostic categories rather than by the diseases themselves. In addition, current diagnostic systems have failed to incorporate results from biological psychiatry and neuroscience. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) launched the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project in 2009 [1, 2] to resolve this issue. The RDoC provides a matrix for a systematic, dimensional, domain-based study of psychiatric disorders that is not based on the established disease entities defined in the DSM or the ICD. The RDoC has considerable potential to define the complexity of the pathological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders. The use of small and heterogeneous study samples, unclear biomarker definitions, and insufficient replication studies are some of the major challenges that need to be overcome in the future.

A recent expert review of schizophrenia is presented as an example of the current state of biological research on psychiatric disorders [3]. The currently established findings on schizophrenia, including its composition, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment, suggest that schizophrenia is unlikely to involve a single common pathophysiological pathway. The boundaries of schizophrenia patients are blurred, and they do not fit into a categorical classification. In other words, schizophrenia needs to be reconceptualized as a broader multidimensional and/or spectral construct. Thus, a new diagnostic system using objective biomarkers should be constructed from a biological and cross-disease perspective that is not limited by diagnostic categories. An investigation into better stratification of clinical populations into more homogeneous delineations is needed for better diagnosis and evaluation and for developing more precise treatment plans. Subtyping on the basis of biologically measurable phenotypes, such as neuroimaging data, aims to identify subgroups of patients with common biological features, thereby allowing the development of biologically based therapies. However, effective strategies for subtyping psychiatric disorders using neuroimaging data have not been developed, and the limitations of the current diagnostic criteria have not been overcome.

Several brain imaging research consortia, such as Enhancing Neuroimaging Genetics Through Meta-analysis (ENIGMA) [4] and the Cognitive Genetics Collaborative Research Organization (COCORO) [5], have conducted large-scale, cross-disease, multicenter studies using a mega-analysis approach on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and autism spectrum disorder [6-11]. Subcortical structures serve as hubs not only for motor control [12] but also for learning [13], memory [14], attention [15], executive functions [16], and emotion [17]. The subcortical and cortico-subcortical circuits are associated with signaling pathways of neurotransmitters such as monoamines and amino acids [18-20]. Dysfunction of these subcortical circuits can be associated with various psychiatric disorders [21, 22]. Mega-analyses of brain MRI studies have reported alterations in subcortical volumes in individuals with psychiatric disorders, which are believed to contribute to characteristic symptoms [11, 23-26].

Using the COCORO cohort, we recently conducted a large multisite study of subcortical volume changes and lateralization changes in 5604 subjects (3078 healthy controls and 2526 patients with psychiatric disorders) [11]. The results revealed larger lateral ventricle volumes in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder; smaller hippocampal volumes in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder; and smaller volumes in the amygdala, thalamus, and nucleus accumbens and larger volumes in the caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus specific to schizophrenia. These brain morphological features are reported to be progressive in individuals with psychiatric disorders [27-31].

In a previous mega-analysis of subcortical volumes in individuals with psychiatric disorders, data-driven classification of 5602 subjects according to subcortical volumes resulted in seven clusters [11]. These seven clusters were integrated into four brain biotype classifications, with extremely or moderately smaller limbic regions, larger basal ganglia, and normal volumes being associated with cognitive/social functioning, for example, intelligence quotient (IQ) and working hours per week. Extremely or moderately smaller limbic regions and larger basal ganglia were associated with severe or mild cognitive/social impairment, whereas normal volumes were characterized by normal cognitive/social functioning.

Impairment of cognitive and social function is widely observed in individuals with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and autism spectrum disorder [32-34]. Cognitive impairments are associated with poorer functional outcomes [35]. A systematic review of meta-analyses examining a wide range of cognitive functions in 12 psychiatric disorders revealed that all disorders were associated with underperformance across cognitive domains [36]. The pattern of cognitive impairment associated with each disorder is unlikely to be specific; however, greater deficits in cognition are observed in patients with schizophrenia. The cognitive impairments observed in individuals with psychiatric disorders are complex; among patients in the same diagnostic category, there is a subgroup of patients with cognitive impairment and a subgroup of patients without cognitive impairment.

Many data-driven studies elucidating brain-based subtypes on the basis of neuroimaging data have been published [37, 38]. The B-SNIP consortium identified and validated more neurobiologically homogeneous psychosis biotypes using batteries of neurocognitive and psychophysiological laboratory measures [39]. Furthermore, the potential of molecular genetics to indicate the biological systems involved in psychopathology suggests the possibility of developing diagnostic classifications with high biological validity using genomics [40]. Although pioneering biotyping is now being actively studied, its clinical significance and utilization are not sufficient. Therefore, we aimed to find a new classification of patients based on data-driven analysis of neuroimaging in this study.

2 Methods

2.1 Subjects

Healthy controls (HC: n = 3077) and patients with schizophrenia (SZ: n = 1499), bipolar disorder (BD: n = 234), major depressive disorder (MDD: n = 598), autism spectrum disorder (ASD: n = 189), or other psychiatric disorders (OM: n = 5) from 14 COCORO participating sites were enrolled in this study (Table S1). All of the subjects were already analyzed in our previous work [11]. Subject inclusion and exclusion criteria by site are described in the Supplementary Method in Appendix S1. In addition, data from cognitive tests, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd edition (WAIS-III) [41] and the Japanese version of the National Adult Reading Test (Japanese Adult Reading Test) [42], were collected at only one site (Osaka). This study was carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (approval number B2023-080) and by each local institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation.

2.2 Neuroimaging Analysis

The detailed imaging processing, quality control, and protocol selection procedures were described previously [10, 11]. In brief, T1-weighted imaging data were processed using FreeSurfer software version 5.3 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The subjects were divided into groups according to site, scanner, and protocol. At sites with multiple protocols, a separate group was defined for each scanner. After quality control and protocol selection, a total of 5604 subjects scanned with 30 protocols were analyzed. The detailed procedures for MRI data-driven X-means nonhierarchical clustering based on eight regions of left and right subcortical volumes normalized according to the distribution of HCs and controlling for sex, age, and intracranial volume using a linear regression model [43] were described previously [11]. We defined four brain biotypes associated with cognitive/social functioning: extremely smaller limbic regions (brain biotype 1), moderately smaller limbic regions (brain biotype 2), larger basal ganglia (brain biotype 3), and normal volumes (brain biotype 4). Two subjects, who were not included in the four brain biotypes in the previous study, were excluded from the present study.

2.3 Definition of an Enlarged Ventricle and Cognitive Impairment

An enlarged ventricle was defined as a ventricle with an average z score > 3 for the left and right lateral ventricle volumes. Left and right lateral ventricle volumes were adjusted according to the distribution of HCs controlling for sex, age, and intracranial volume using a linear regression model [43] and divided by the standard deviation of the HCs, yielding a z score for the left and right lateral ventricle volumes of each subject. Cognitive impairment was defined as a moderate or severe decrease (20 points or more) in the current intellectual quotient (IQ) compared with the premorbid IQ [44-46]. The cognitive impairment score was defined by subtracting the premorbid IQ from the current IQ. The current IQ was measured with the full-scale Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III [41], and the premorbid IQ score was estimated with the Japanese Adult Reading Test [42]. Severe cognitive impairment was defined as a decrease of 30 points or more, moderate impairment was defined as a decrease of 20–30 points, mild impairment was defined as a decrease of 15–20 points, borderline impairment was defined as a decrease of 10–15 points, and normal impairment was defined as a decrease of < 10 points [44].

2.4 Evaluation of Electroencephalography Data

Digital 19-channel electroencephalography (EEG) signals were recorded via a Nihon–Kohden (Inc., Tokyo, Japan) system, with electrodes positioned according to the International 10–20 system. EEG activity was acquired using a linked ear reference, sampled at 500 Hz, and filtered offline between 1 and 30 Hz. The impedance was kept below 5 kΩ.

2.5 Copy Number Variation Analysis

The copy number variation (CNV) calling method and quality control (QC) procedure were performed as previously reported [47]. In brief, array comparative genomic hybridization (probe spacing ~2.5 kb) analysis was conducted according to the manufacturer's protocols (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI, USA and Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The statistical variance of the log2 ratio for each probe was calculated with subsequent QC: samplewise QC (subjects with a QC score > 0.15 and with > 80 or 45 CNVs on the NimbleGen and Agilent chips, respectively, were removed) and CNV-wise QC [CNVs were removed on the basis of size (< 10 kb), low probe density (< 1 probe/15 kb), overlap with segmental duplication (> 70%), and Y chromosome, with the exception of XXY]. Finally, common CNVs (> 1%) were filtered for the final analysis. The definition of a pathological CNV was the same as that used in a previous study [47] and was in accordance with the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG): clinically significant CNVs included “pathogenic” CNVs and CNVs of “uncertain clinical significance.” The detailed procedure was described in our previous report [47].

2.6 Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 28.0 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan) was used to perform the statistical analysis. Categorical data were analyzed with either the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, and numerical data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the performance of the ventricle volumes in classifying brain biotype 1. To define statistical significance, we used two-sided tests and set the type I error rate (p value) to 0.05.

3 Results

A total of 5602 participants, including healthy controls (n = 3077) and patients with schizophrenia (n = 1499), bipolar disorder (n = 234), major depressive disorder (n = 598), autism spectrum disorder (n = 189), and other psychiatric disorders (n = 5), were clustered according to brain subcortical volumes, and four brain biotype classifications were identified: extremely smaller limbic regions (brain biotype 1: n = 110), moderately smaller limbic regions (brain biotype 2: n = 566), larger basal ganglia (brain biotype 3: n = 679), and normal volumes (brain biotype 4: n = 4247), which were associated with cognitive/social functioning in a previous paper (Table 1) [11].

| Total | HC | SZ | BP | MDD | ASD | OM | Age | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5602 (100%) | 3077 (100%) | 1499 (100%) | 234 (100%) | 598 (100%) | 189 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 37.3 (14.0) | 2714 (48.4%) |

| Brain biotype 1 | 110 (2.0%) | 13 (0.4%) | 69 (4.6%) | 9 (3.8%) | 16 (2.7%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (20.0%) | 46.4 (16.9) | 41 (37.3%) |

| Brain biotype 2 | 566 (10.1%) | 163 (5.3%) | 273 (18.2%) | 28 (12.0%) | 87 (14.5%) | 15 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 40.4 (15.7) | 258 (45.6%) |

| Brain biotype 3 | 679 (12.1%) | 177 (5.8%) | 389 (26.0%) | 34 (14.5%) | 64 (10.7%) | 15 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37.4 (15.2) | 317 (46.7%) |

| Brain biotype 4 | 4247 (75.8%) | 2724 (88.5%) | 768 (51.2%) | 163 (69.7%) | 431 (72.1%) | 157 (83.1%) | 4 (80.0%) | 36.7 (13.4) | 2098 (49.4%) |

- Note: The number and proportion of subjects at each diagnosis, age (mean and standard deviation), and sex (female number and proportion) among the brain biotypes are shown.

- Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BP, bipolar disorder; HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; OM, other psychiatric disorders (personality disorder, conversion disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social anxiety disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified); SZ, schizophrenia.

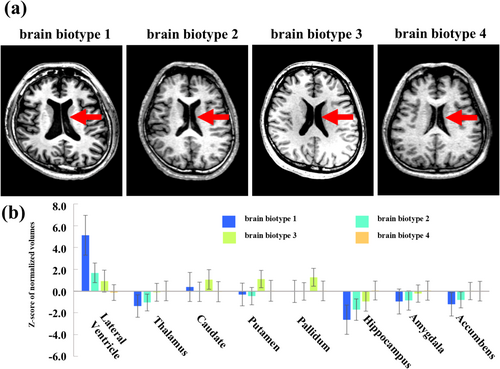

To clarify the clinically recognizable features of the four brain biotypes of subcortical structures, typical axial brain MR images, and subcortical volumes of brain regions, including the lateral ventricle, thalamus, caudate, putamen, pallidum, hippocampus, amygdala, and accumbens of the four brain biotypes are shown in Figure 1a,b. Images of subjects with brain biotype 1 showed a remarkably larger ventricle volume (z score = 5.1 ± 1.8) than those of subjects with other brain biotypes (z scores, brain biotype 2 = 1.7 ± 0.9, brain biotype 3 = 0.9 ± 1.0, brain biotype 4 = −0.1 ± 0.7). Another major feature among the biotypes was a difference in hippocampal volume (z scores, brain biotype 1 = −2.6 ± 1.3; brain biotype 2 = −1.7 ± 0.8; brain biotype 3 = −1.0 ± 0.9; brain biotype 4 = 0 ± 0.9), with no other major differences in other subcortical structures. Therefore, the main clinically recognizable feature of brain biotype 1 was the enlarged ventricle.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed that ventricle volume was able to discriminate between brain biotype 1 and other brain biotypes (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.999, p = 4.9 × 10−72). The sensitivity and specificity of enlarged ventricles to distinguish between brain biotype 1 and the other brain biotypes were 99.1% and 98.6%, respectively, when an enlarged ventricle was defined by a ventricle volume of a z score of three or more. The proportions of subjects with enlarged ventricles in each brain biotype are shown in Table 2. Enlarged ventricles were observed in 99.1% of the subjects with brain biotype 1, 8.8% of the subjects with brain biotype 2, 3.5% of the subjects with brain biotype 3, and 0.1% of the subjects with brain biotype 4, suggesting that enlarged ventricles were a representative feature of brain biotype 1.

| Total | EV | EV (% in each brain biotype) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5602 | 186 | 3.3% |

| Brain biotype 1 | 110 | 109 | 99.1% |

| Brain biotype 2 | 566 | 50 | 8.8% |

| Brain biotype 3 | 679 | 24 | 3.5% |

| Brain biotype 4 | 4247 | 3 | 0.1% |

- Note: The number and proportion of subjects with EVs in each brain biotype are shown. EV was defined as an average z score > 3 for left and right lateral ventricle volumes.

- Abbreviation: EV, subjects with enlarged ventricles.

Next, we examined the differences in brain structure between subjects with enlarged ventricles and those with nonenlarged ventricles (Table 3). Subjects with enlarged ventricles had larger lateral ventricle volumes (z score = 4.41 ± 1.66) than those with nonenlarged ventricles (z score = 0.13 ± 0.92). Smaller volumes of the hippocampus, thalamus, and total cortex were also observed in subjects with enlarged ventricles than in those with nonenlarged ventricles. With respect to the percentages of subjects with enlarged ventricles with psychiatric disorders, the highest percentage was found in patients with schizophrenia (7.3%), followed by approximately 3%–5% in patients with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and autism spectrum disorder, and 1% in healthy individuals (Table 4). While an enlarged ventricle was shown to be a biomarker with high sensitivity and specificity for discriminating brain biotype 1, some healthy individuals exhibited enlarged ventricles. Thus, the use of an enlarged ventricle alone is not sufficient for stratifying psychiatric disorders on the basis of objective examination, suggesting that additional stratification markers are needed.

| EV | Non-EV | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral ventricle | 4.41 (1.66) | 0.13 (0.92) | < 1.0 × 10 −15 |

| Thalamus | −1.09 (1.03) | −0.11 (0.94) | < 1.0 × 10 −15 |

| Caudate | 0.30 (1.34) | 0.07 (0.99) | 1.5 × 10−2 |

| Putamen | −0.15 (1.12) | 0.10 (1.01) | 8.7 × 10 −4 |

| Pallidum | 0.09 (1.09) | 0.15 (0.97) | 3.0 × 10−1 |

| Hippocampus | −1.97 (1.46) | −0.25 (1.07) | < 1.0 × 10 −15 |

| Amygdala | −0.72 (1.12) | −0.09 (0.92) | 1.3 × 10 −15 |

| Accumbens | −0.88 (1.16) | −0.09 (0.91) | < 1.0 × 10 −15 |

| Total cortical volume | −1.71 (1.99) | −0.26 (1.14) | < 1.0 × 10 −15 |

| The global mean cortical thickness | −1.09 (1.79) | −0.18 (1.14) | 2.1 × 10 −12 |

| Total cortical surface area | −0.26 (1.38) | −0.13 (1.10) | 2.5 × 10−1 |

- Note: The means and standard deviations of the normalized values (z scores) of subcortical volumes in subjects with EV (n = 186) and non-EV (n = 5416) are shown. The means and standard deviations of the normalized values (z scores) of cortical volume, thickness, and surface area in EVs (n = 175) and non-EVs (n = 5197) are also shown. The mean normalized values of subcortical volumes and total cortical volume were adjusted for age, sex, and intracranial volume in each MRI scanner. The mean normalized values of the global mean cortical thickness and total cortical surface area were adjusted for age and sex in each MRI scanner. The data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test. The p value adjusted by using Bonferroni correction for post hoc tests was defined as significant. Statistically significant associations (p value < 0.0045 (0.05/11)) are highlighted in bold.

- Abbreviations: EV, subjects with enlarged ventricles; non-EV, subjects without enlarged ventricles.

| Total | SZ | BP | MDD | ASD | OM | HC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | 186 (3.3%) | 109 (7.3%) | 11 (4.7%) | 26 (4.3%) | 7 (3.7%) | 1 (20.0%) | 32 (1.0%) |

| Non-EV | 5416 (96.7%) | 1390 (92.7%) | 223 (95.3%) | 572 (95.7%) | 182 (96.3%) | 4 (80.0%) | 3045 (99.0%) |

- Note: The number and proportion of patients classified as having EV or non-EV at each time point are shown. EV is defined as an average z score > 3 for left and right lateral ventricle volumes.

- Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BP, bipolar disorder; EV, enlarged ventricle; HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; non-EV, without an enlarged ventricle; OM, other psychiatric disorders (personality disorder, conversion disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social anxiety disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified); SZ, schizophrenia.

The enlarged ventricles and small cortical and subcortical volumes of subjects with brain biotype 1 can be assumed to indicate either an originally small brain or progressive atrophy of the brain. Progressive atrophy of brain structures and cognitive impairment has been reported to occur in patients with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders [3, 22]. Therefore, we attempted to further classify 33 subjects with enlarged ventricles for whom data were available for a comparison of clinical and biological features according to cognitive impairment (Table 5). Cognitive impairment was defined by a moderate or greater difference between the current and premorbid IQ scores [44]. In total, 27.3% of the subjects with enlarged ventricles exhibited cognitive impairment (cognitive impairment score = −27.1 ± 5.2, current IQ = 66.9 ± 10.5, premorbid IQ = 94.0 ± 13.2), and 72.7% of the subjects with enlarged ventricles did not exhibit cognitive impairment (cognitive impairment score = −3.8 ± 10.3, current IQ = 102.9 ± 14.7, premorbid IQ = 106.7 ± 10.3). The participants with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment included 8 patients with schizophrenia and one patient with autism spectrum disorder; no healthy subjects were included in this subgroup. The subjects with enlarged ventricles without cognitive impairment included 9 patients with schizophrenia, 9 healthy controls, and 6 patients with other psychiatric disorders. The proportion of patients with schizophrenia was significantly greater in those with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment than in those with enlarged ventricles without cognitive impairment (88.9% and 37.5%, respectively) (Table 5). By incorporating cognitive impairment as an additional stratification marker, only patients with psychiatric disorders will be stratified. There were no differences in age, sex, years of education, or ventricle volume between subjects with enlarged ventricles and those with cognitive impairment and subjects with enlarged ventricles without cognitive impairment.

| EV and CI | EV and non-CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 9 (27.3%) | 24 (72.7%) | |

| Female (%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (16.7%) | 0.36a |

| Age, mean (SD) | 31.6 (11.5) | 39.1 (19.1) | 0.49c |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 13.1 (1.8) | 14.3 (2.7) | 0.19c |

| Cognitive impairment score, mean (SD) | −27.1 (5.2) | −3.8 (10.3) | 5.2 × 10 −8c |

| Current IQ, mean (SD) | 66.9 (10.5) | 102.9 (14.7) | 1.6 × 10 −6c |

| Premorbid IQ, mean (SD) | 94.0 (13.2) | 106.7 (10.3) | 0.011 c |

| Ventricle volume, mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.6) | 0.54c |

| Psychiatric disorder classification: SZ/BP/MDD/ASD/OM/HC (% of SZ) | 8/0/0/1/0/0 (88.9%) | 9/0/1/4/1/9 (37.5%) | 0.017 b |

| EEG abnormality (abnormal/total) (%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 0/11 (0%) | 2.5 × 10 −3b |

| Rare CNV (N/total) (%) | 3/7 (42.9%) | 0/12 (0%) | 0.036 b |

- Note: Diagnostic and biological features of individuals with EVs and CIs and those with EVs and non-CIs are shown. An EV was defined as an average z score > 3 for the left and right lateral ventricle volumes. CI was defined as a decrease of ≥ 20 points in the cognitive impairment score, which was calculated by subtracting the premorbid IQ (Japanese Adult Reading Test [JART]) from the current IQ (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [WAIS]). Given that data for EEG and CNV were missing, the available data (EEGs: seven individuals in the EV and CI groups and 11 individuals in the EV and non-CI groups; CNVs: seven individuals in the EV and CI groups and 12 individuals in the EV and non-CI groups) were analyzed. Categorical data were analyzed with either the chi-square testa or Fisher's exact testb, and numerical data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney testc. Statistically significant associations (p value < 0.05) are highlighted in bold.

- Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BP, bipolar disorder; CI, cognitive impairment; CNV, copy number variation; EV, enlarged ventricles; MDD, major depressive disorder; N, number of subjects; OM, other psychiatric disorders (personality disorder: conversion disorder: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: social anxiety disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified); SD, standard deviation; SZ, schizophrenia.

We further investigated the clinical and biological characteristics of patients with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment. Individuals with insufficient information were omitted from the subsequent analysis. Five of the seven patients with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment had abnormal EEG signals, which were significantly more prominent than those in patients with enlarged ventricles without cognitive impairment (no abnormal EEG signals in 11 patients) (Table 5). The types of EEG abnormalities included one case of focal spike-and-wave complex at F7, T3, and T5 with diffuse high-amplitude slow waves; one case of focal spike-and-wave complex at F3, Fz, and F4; and three cases of diffuse slow waves. Three of the seven patients with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment had rare pathological CNV, which was significantly more common than those in subjects with enlarged ventricles without cognitive impairment (no rare pathological CNVs in 11 subjects) (Table 5). The types of rare pathological CNVs included one 22q11.21 deletion, one 7q11.23 duplication, and one 7q36.2 deletion. Patients stratified by enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment were found to have features of gross neurophysiological dysfunction that could be detected by clinical EEG and rare pathological CNV.

4 Discussion

This study proposes a new and biologically defined mental disease by stratifying a group of patients with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment (EVCI) characterized by a high rate of diagnosis of schizophrenia, EEG abnormalities, and rare pathological variants using MRI data-driven analysis of a large sample of cross-disorders. Although there have been many classification studies of psychiatric disorders based on large-scale data-driven analysis, to our knowledge, this is the first unique report to stratify a group of patients according to these novel biological features. The strategy for classifying patient groups that can be biologically stratified beyond the conventional diagnostic framework of psychiatric disorders is shown in Table 6. To achieve this stratification, it is necessary to collect multimodal big data on various psychiatric disorders, perform hypothesis-free, data-driven analysis to classify them, and then identify the features that can be detected in clinical settings on the basis of the data used for the classification. To stratify patients according to specific pathologies, further reclassification should be performed with data not used for the first classification, after which the clinical and biological characteristics of the stratified patient groups should be identified. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report the application of such a strategy.

| Strategy | EVCI as an example | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Collection of multimodality big data across psychiatric disorders | Brain MRI imaging data from 5602 patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and autism spectrum disorder and healthy subjects, accompanied by clinical information, cognitive and social function data, neurophysiological data, genomic information data, and biological samples |

| Step 2 | Identification of brain biotypes based on data-driven classification of neuroimaging across psychiatric disorders | Identified brain biotype 1 with small limbic system and enlarged ventricles |

| Step 3 | Identification of features that can be detected in clinical settings by reviewing classified subject data | Identification of biotype 1 represented by enlarged ventricles |

| Step 4 | Narrowing down to more homogeneous patient groups by reclassification using data features not used in data-driven classification | Identification of patients stratified by cognitive impairment in addition to enlarged ventricles |

| Step 5 | Identification of clinical characteristics in stratified patient groups | High proportion of diagnosis of schizophrenia, EEG abnormality and pathological rare copy number variation |

- Note: EVCI: patients with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment.

Since eight of the nine patients with EVCI included in this study had schizophrenia, we evaluated enlarged ventricles, cognitive impairment, EEG abnormalities, and rare pathological CNVs and compared them with those in patients with schizophrenia in general. An enlarged ventricle has been repeatedly reported in patients with schizophrenia since the 1970s [48, 49], and recent large meta- and mega-analyses have also reported enlarged ventricles in patients with schizophrenia [11, 50]. The effect size of an enlarged ventricle in patients with schizophrenia is approximately 0.5, and enlarged ventricles have been reported to a smaller extent in psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia. The effect size of an enlarged ventricle in patients with EVCI is more than three by definition, which is considered an extreme case among psychiatric disorders. Since 7.3% of patients with schizophrenia in this study had enlarged ventricles and eight out of 17 schizophrenia patients with enlarged ventricles had cognitive impairment, 3.4% of patients with schizophrenia had EVCI. As extremely large ventricles in some patients with schizophrenia have also been reported [49], it is possible that these patients may have EVCI.

Cognitive impairments have long been known as clinical features of schizophrenia, and clinical practice guidelines now include recommendations for the treatment of cognitive impairments; moreover, new treatments for cognitive impairment are being actively developed [51]. Cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia present prior to onset and persist and/or worsen throughout the course of the illness [3]. Neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia patients stratified by cognitive impairment have reported enlarged ventricles and decreased subcortical and cortical volumes [22, 48, 49]. It has also been reported that enlarged ventricles are correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia [22, 49, 52]. A recent review of schizophrenia patients revealed that an enlarged ventricle is an established finding and that cognitive impairment is now recognized as a further clinical feature of the disorder, supporting the theory of a subpopulation of patients with schizophrenia with enlarged ventricles and cognitive impairment proposed in this study [53]. Patients with EVCI did not have gait disturbance or urinary incontinence among three iNPH symptoms (dementia, gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence) [54]. Also, the average age of patients with EVCI was in their 30s, whereas the incidence of iNPH increases in older age and ranges from 60s to 70s [55]. Thus, patients with EVCI may develop iNPH in the future. A high frequency of slow wave and focal spike-and-wave complexes was observed in patients with EVCI. A high frequency of abnormal EEG signals (SZ: 20%–40%; HC: 0%–10%) and a variety of slow waves have been reported in patients with schizophrenia [56, 57]. Intermittent rhythmic delta or theta activity was also reported in 7% of patients with schizophrenia compared with 1% of normal subjects [58]. The presence of a focal spike-and-wave complex is a common finding in epilepsy. A review reported that the proportion of patients with schizophrenia associated with epilepsy ranged from 0.4% to 7.3% [59]. The reported occurrence of slow waves and possible epileptic abnormal waves in some schizophrenia patients is consistent with neurophysiological changes among large-scale brain networks in schizophrenia patients [53]. Thus, it is possible that EVCI might be associated with neurophysiological abnormalities related to the disruption of brain networks.

Three rare pathological CNVs were found in patients with EVCI, of which 22q11.21 deletion and 7q11.23 duplication are previously known pathogenic CNVs in schizophrenia [60]. Although the high incidence of known pathogenic CNVs in patients with EVCI is a high-impact event, known pathogenic CNVs are indicated not only in schizophrenia but also in a variety of phenotypes (e.g., intellectual disability and ASD with 22q11.21 deletion). The CNVs identified in this study, such as 22q11.2deletion, are not only associated with existing diseases but may also indicate a risk for EVCI, which is a characteristic phenotype [61]. Thus, it is worthwhile to propose a new group of patients with EVCI for genetic research in psychiatry. Genetic analysis in patients with EVCI in whom known pathogenic CNVs were not found is important because these patients exhibit a characteristic phenotype, and if rare variants are found, they may be variants that should be prioritized even if they were previously unknown.

This study has several limitations. We identified nine patients with EVCI from 5602 patients and healthy controls; however, we did not report patients with EVCI from other cohorts. Further reproducibility studies with large sample sizes are needed. Since ventricular volume could be influenced by age, the neuroimaging data were corrected for age in this analysis. On the other hand, we did not correct for a medication effect in this report. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of the effects of antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines on brain structure have been inconclusive, some reporting effects while others do not [62-65]. EVCI was found in 3.4% of patients with schizophrenia and 0.7% of patients with autism spectrum disorder but not in those with bipolar disorder or major depression. EVCI could be considered a very small outlier subgroup with biologically extreme phenotypes that might well be excluded from many studies.

We did not report the clinical course, symptoms, treatment responsiveness, or outcomes of the nine patients in detail. We also did not report the details of other domains of cognition, EEG, or neuroimaging findings, or the results of genomic analyses other than CNVs. Historical data need to be accessed, and the possibility of another patient examination or reexamination should be considered. The consideration of EVCI features in individuals with psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia was poor, as there were few cognitive data on other psychiatric disorders. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to increase the amount of cognitive data available for individuals with other psychiatric disorders. The present results are based on a cross-sectional neuroimaging study, so it is unclear whether the enlarged ventricles were originally larger or whether they progressively increased in size. In the future, longitudinal studies should be conducted to clarify the true nature of enlarged ventricles. Finally, the strategy of this study was reported for the first time in this report, and the reproducibility of the methodology has not been tested. It is necessary to verify other brain biotypes and whether similar patient stratification is possible on the basis of data-driven analysis using neuroimaging indices and other phenotypes.

5 Conclusions

We propose a new subgroup of psychiatric disorders characterized by markedly large lateral ventricle volume, cognitive impairment, a high proportion of schizophrenia diagnoses, EEG abnormalities, and rare pathological CNVs. Further studies, including detailed clinical information on nine EVCI patients, a prospective cohort for psychiatric disorders, neurophysiology, genetics, animal models, and neurobiology, are warranted to elucidate the etiology and develop treatments for patients with EVCI in the future.

Author Contributions

Y.Y. was critically involved in data collection and data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.I. was involved in the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. Junya M., T.O., M.I., I.K., Naohiro O., Masaki F., and K.N. were involved in the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. K.O., Hidenaga Y., and Michiko F. were involved in data collection and data analysis. C.S., K.M., N.H., T.T., Michihiko K., H.T., N.H., H.N., M.Y., D.S., K.K.T., Masataka K., T.K., E.I., Y.O., A.T., M.N., Manabu K., H.I., Y.H., G.O., Jun M., Shusuke N., O.A., R.Y., Shin N., Hidenori Y., Norio O., and K.K. were involved in data collection and contributed to the interpretation of the data. R.H. supervised the entire project, collected the data, and was critically involved in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data. All of the authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Kazuyuki Nakagome at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry for critical advice on this manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Review Board: This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (approval number B2023-080) and by each local institutional review board.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation.

Conflicts of Interest

Kazutaka Ohi and Reiji Yoshimura are editorial board members of Neuropsychopharmacology Reports and co-authors of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication. Except for that, no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the disclosure of the individual data was not included in the research protocol and because consent for public data sharing was not obtained from the participants. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.