Gender Differences in the Effects of Trust on Substance Abuse Severity Among Incarcerated Stimulant Offenders in Japan

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant from the Division of Research, National Center for Addiction Services Administration (2023-01), which was the project funding for addiction prevention and treatment by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. It was conducted as part of a research project titled “Research on understanding and support for stimulant drug offenders (2023-01)” by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

ABSTRACT

Background

Treatment of stimulant offenders in Japan is an urgent issue. One of the more recent support approaches for stimulant offenders in Japan is to understand and support them based on a self-medication hypothesis; however, the effect of trust on substance abuse severity among incarcerated stimulant offenders has not been examined. Additionally, while accounting for gender differences is essential when providing support for them, these differences have not also been examined.

Purpose

To investigate gender differences in the effect of trust on substance abuse severity in a national sample of stimulant offenders in Japanese prisons.

Method

Data from 586 incarcerated stimulant offenders who answered a nationwide questionnaire were analyzed. Descriptive statistics and multiple regression analyses were used to assess the association between trust and the severity of substance abuse.

Results

Compared with men, women reported lower trust in others; moreover, their distrust in others and substance abuse severity were greater. After controlling for confounding factors, multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for men and women, with trust as the independent variable and substance abuse severity as the dependent variable. The models for both men (R2 = 0.180, p < 0.001) and women (R2 = 0.236, p < 0.001) were significant. Trust in oneself influenced drug dependence severity for men (β = −0.183, p < 0.01), whereas distrust in others influenced drug dependence severity for women (β = 0.185, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that gender differences must be considered when supporting stimulant offenders in prison.

1 Introduction

1.1 Current State of Substance Use in Japan

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [1], methamphetamine is the most widely abused illicit drug in the world, after marijuana and opioids. This drug has the potential to cause various life-altering problems, including substance use disorders, mental health problems, violent behavior, and physical illness [2]; caring for methamphetamine users is a serious public health concern in countries around the world [3]. Japan has one of the lowest lifetime illicit drug use rates among individuals [4]. Among the general Japanese population, these rates have been reported as 1.4% for cannabis, 0.9% for organic solvents, 0.5% for new psychoactive substances, and 0.3% for methamphetamine, MDMA, and heroin [5]; however, these rates are lower than those reported in similar studies in Europe and the United States [6, 7].

Although the lifetime drug use rate in Japan is low according to international comparisons, the treatment of substance users in Japan, particularly methamphetamine users, remains an important issue. A nationwide hospital survey on drug-related psychiatric disorders in Japan revealed that methamphetamine was the substance with the highest percentage of lifetime use (60.6%), followed by over-the-counter drugs (31.6%), and anti-anxiety drugs (28.2%). Additionally, this survey showed that the substance that most commonly triggered the need to see a doctor was methamphetamine (49.7%), followed by sleeping pills/anti-anxiety drugs (17.6%), and over-the-counter drugs (11.1%) [8]. Importantly, although Japan has traditionally maintained a zero-tolerance policy for illegal drugs, and the use of methamphetamine has been strictly prohibited by the Stimulants Control Act [9], the number of people arrested for violating the Stimulants Control Act in Japan has remained around 10 000 people per year since the 2000s. Moreover, since 2010, the situation has continued to cause concern, as the percentage of repeat stimulant offenders who have violated the same Act has exceeded 60%. Furthermore, the rate of reimprisonment for the same offense against the Stimulants Control Act within five years of being released from prison was 43.8%, which is higher than that for other offenses [10]. Therefore, dealing with stimulant offenders is an urgent issue.

1.2 Theoretical Frameworks of Substance Use Treatment: Focusing on Trust

Substance use behavior has been examined using a variety of theoretical frameworks, including negative reinforcement (“pain avoidance”), positive reinforcement (“pleasure seeking”), incentive salience (“craving”), stimulus response learning (“habits”), inhibitory control dysfunction (“impulsivity”) [11], and reward deficiency syndrome [12]. One of the more recent support approaches for substance users in Japan is to understand and support them based on the self-medication hypothesis [13]. Self-medication hypothesis is a working hypothesis that argues that substance users cope with the pain of loneliness and interpersonal distrust caused by harsh experiences in their early life [13]. Indeed, a high percentage of substance users are known to have experienced interpersonal distrust, including Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) [4] or childhood abuse [14-16]. Additionally, it has been noted that interpersonal distrust owing to chronic traumatic experiences in early life underlies the process that leads from ACEs to substance use [17].

Trust is extremely important to human life. Erikson described trust as “an essential trust of others as well as a fundamental sense of one's own trustworthiness” [18]. By contrast, damaged or lack of trust—or distrust—is a dynamic part of trust that is expressed in ways that negatively impact relationship with others and oneself [18]. Additionally, Govier discussed the characteristics of a trusting and distrusting person [19]. He points out that a trusting person will understand themselves and others in a positive way; will tend to experience a benevolent world; find attractive, trustworthy friends and have meaningful intimate relationships; and will thereby have an optimistic sense of the world and their future within it. On the other hand, he also indicated that someone who is suspicious, cynical, and distrustful, with a negative sense of self and others, will construct and encounter a different world.

In Japan, the concept of trust, which integrates the concept of Rotter [20] based on Erikson's theory [18], has been proposed [21]. Amagai defined interpersonal trust as “a feeling of being able to trust toward oneself or others (other objects)” and developed a multidimensional scale that measures trust from three aspects: trust in oneself, trust in others, and distrust in others [21]. In Japan, this scale has been used to examine the relationship between trust and self-esteem [22], the relationship between trust and interpersonal dependence needs [23], and the influence of trust in oneself and others on one's view of Japanese society [24]. Additionally, in substance abuse research, Itabashi et al. examined distrust in other mediated models of the relationship between childhood adversity and drug abuse severity [25].

As the foregoing discussion indicates, many substance users have the possibility of depending on substances as a means to avoid pain because they cannot trust people. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the association between trust and severity of drug abuse, a topic that has not received sufficient attention.

1.3 Research on Stimulant Offenders in Japan

A few peer-reviewed studies on stimulant offenders in Japan have been conducted. For instance, some are about their characteristics [26, 27], the substance dependence process [28], the triggers for using stimulants [29, 30], the relationship between drug abuse severity and recidivism [31], gender differences in the relationship between methamphetamine use and high-risk sexual behavior [9], child abuse victimization [15], and the prevalence of ACEs and their association with suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury [4]. However, no studies have focused on the relationship between trust and substance abuse severity among stimulant offenders.

1.4 The Purpose of This Study

This study aimed to examine the effect of trust on substance dependence severity in a national sample of stimulant offenders incarcerated in Japanese penal institutions. Previous studies have reported gender differences in the characteristics of stimulant offenders [9, 30]; thus, gender differences were also considered in the analyses. In the present study, we hypothesized that the higher the score for distrust in others, the greater the substance abuse severity would be.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

This research was conducted as a secondary analysis of the original project titled “Health survey for drug offenders 2017,” collected by the Research and Training Institute, Ministry of Justice, Japan. Data for participating men in the present study were collected from July to August 2017 and for women from July to November 2017 at all 78 prisons, excluding medical prisons, in Japan. The criteria for selecting participants were as follows: (1) newly incarcerated to violate the Stimulants Control Law, (2) inmates who had used methamphetamine even once in their lifetime, (3) inmates who could read and write Japanese, and (4) inmates who provided informed consent.

Of the 806 inmates (542 men and 264 women) who were selected from the nationwide data of the penal institutions in Japan and invited to participate in this study, 107 refused to participate, and 699 (462 men and 237 women) answered the self-administered survey (response rate: 86.7%). The representativeness of this sample has been confirmed by Shimane et al. [31], and detailed demographic characteristics are described in Shimane et al. [9] and Takahashi et al. [4] In the present study, 113 participants' data were excluded because of missing values, resulting in a final analysis of 586 people, comprising 393 men (average age 43.96 years, SD = 10.31, range 22–72) and 193 women (average age 41.34 years, SD = 8.81, range 24–69).

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Dependent Variables

2.2.1.1 Trust

The scale used to measure trust was a self-administered 4-point Likert scale consisting of 18 items that multidimensionally capture three aspects of trust: trust in oneself, trust in others, and distrust in others. It reportedly has good reliability and validity [32]. Trust in oneself comprised five items (score range 5–20; e.g., “I consider myself trustworthy”), trust in others comprised five items (score range 5–20; e.g., “In general, I think people are trustworthy”), and distrust in others comprised eight items (score range 8–32; e.g., “If I'm not careful, others will try to take advantage of my weaknesses”). Cronbach's alpha for the three dimensions in this study was 0.729, 0.743, and 0.705, respectively.

2.2.2 Independent Variables

2.2.2.1 Drug Abuse Screening Test 20 (DAST-20)

The DAST-20 is a self-report scale developed by Canadian psychologist Skinner [33] for rating the severity of drug problems. In this study, we used the Japanese version of the DAST-20, the reliability and validity of which were verified by Shimane et al. [34]. Cronbach's alpha was 0.803.

2.2.3 Control Variables

The control variables in this study were gender, age, age at first stimulant use, number of drugs used per month, number of times in prison for drug use, and childhood adversity score. These variables reflect the findings showing that early drug use is associated with a range of clinical problems [35], that the severity of drug problems and frequency of imprisonments for drug use increase with age [31], and that childhood adversity increases the risk of drug use [36]. Moreover, these variables were used as continuous variables. We referred to Takahashi et al. [4] for the content of the ACE items and the method of calculating the score.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

First, all descriptive statistics were calculated. Our analysis was conducted for all participants and by gender. For analyses of all participants, correlations between pairs of variables were calculated using Pearson's correlation coefficient. After that the scores for distrust in others, trust in others, and trust in oneself were then centralized and interaction terms for each trust score and gender were created; the multiple regression analysis was conducted with trust as the independent variable, age, age at first stimulant use, number of stimulant use per month, number of times incarcerated for drug use, ACE scores, interaction terms for the three trust scores and gender as control variables, and the severity of drug dependence as the dependent variable. For the analyses by gender, correlations between each variable were calculated, and then multiple regression analyses were conducted with trust as the independent variable, age, age at first stimulant use, number of stimulant use per month, number of times incarcerated for drug use, ACE score as control variables, and the severity of drug dependence as the dependent variable. The value of R2, which is the coefficient of determination in multiple regression analysis, was evaluated using 0.0196 for small, 0.1304 for medium, and 0.2592 for large, following Cohen [37].

2.4 Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association. Informed consent was obtained from each participant during the original survey. After the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and the Ministry of Justice's Legal Research Institute signed a sample provisional agreement in April 2017, researchers obtained and analyzed anonymized datasets for secondary analysis. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan (approval number: A2017–107).

3 Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic variables for all participants by gender. Men were more likely than women to be imprisoned more often for drug offenses and tended to be older at the time of the survey and first drug use. In contrast, women were more likely to use drugs more frequently per month than men in addition to higher levels of ACE scores, distrust in others, and the severity of drug dependence, whereas lower trust in others was lower level.

| Total | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 586 | N = 393 | N = 193 | ||

| Age | 43.10 ± 9.91 | 43.96 ± 10.31 | 41.34 ± 8.81 | < 0.001 |

| First onset age | 22.95 ± 7.30 | 23.13 ± 6.96 | 22.60 ± 7.94 | 0.438 |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 8.65 ± 9.42 | 8.01 ± 8.99 | 9.99 ± 10.18 | < 0.025 |

| Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 2.80 ± 2.00 | 3.01 ± 2.14 | 2.38 ± 1.61 | < 0.000 |

| ACE score | 2.42 ± 2.32 | 2.05 ± 2.16 | 3.20 ± 2.46 | < 0.000 |

| Trust in oneself | 14.03 ± 3.18 | 14.06 ± 3.16 | 13.96 ± 3.22 | 0.707 |

| Trust in others | 13.87 ± 3.55 | 14.08 ± 3.54 | 13.45 ± 3.55 | < 0.043 |

| Distrust in others | 19.91 ± 4.76 | 19.58 ± 4.73 | 20.58 ± 4.76 | < 0.017 |

| DAST-20 | 9.61 ± 4.10 | 9.26 ± 3.90 | 10.34 ± 4.42 | < 0.003 |

- Abbreviations: ACE, adverse childhood experience; DAST-20, drug abuse screening test 20.

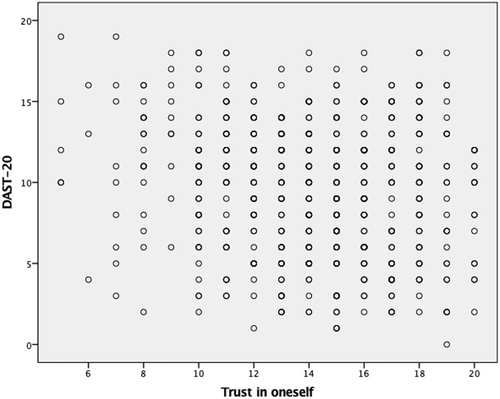

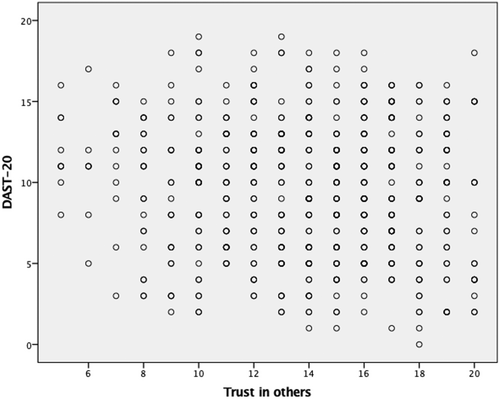

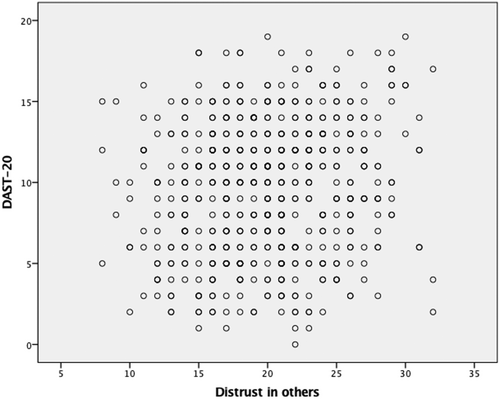

3.2 Relationship Between Trust and Severity of Drug Dependence for All Participants

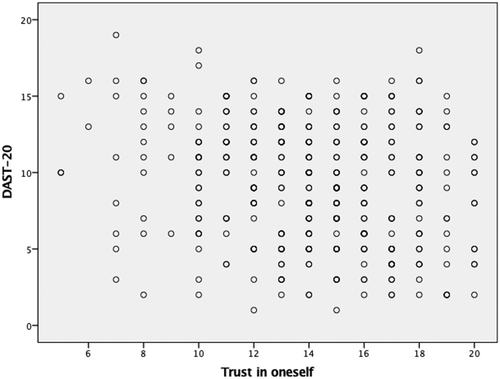

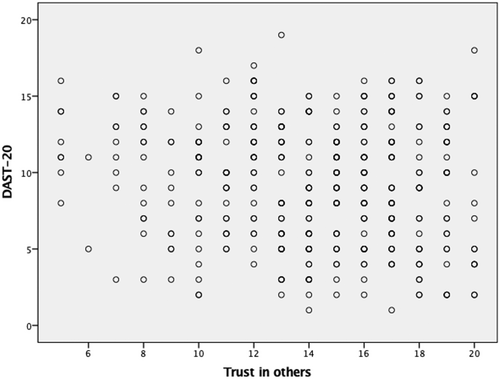

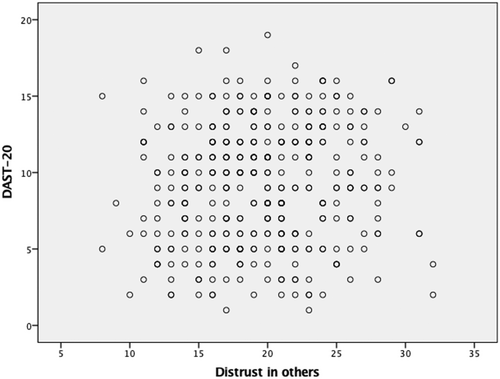

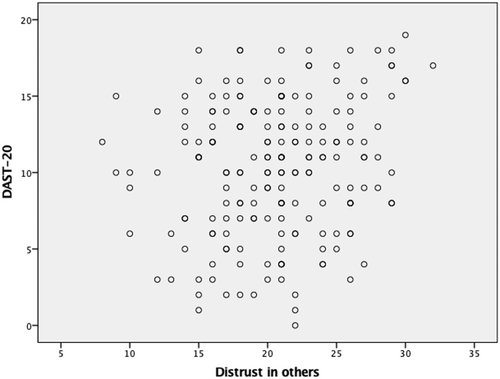

Prior to the multiple regression analysis, a correlation analysis was conducted between trust and the severity of drug dependence for all participants. The correlation coefficient between trust in oneself and severity of drug dependence was r = −0.154 (p < 0.01), the correlation coefficient between trust in others and severity of drug dependence was r = −0.096 (p < 0.05), and the correlation coefficient between distrust in others and severity of drug dependence was r = 0.143 (p < 0.01) (Table 2, Figures 1-3).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | ||||||||

| 2. First onset age | 0.275** | — | |||||||

| 3. Stimulant use frequency per month | −0.156** | −0.150** | — | ||||||

| 4. Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.586** | −0.097* | −0.041 | — | |||||

| 5. ACE score | −0.140** | −0.084* | 0.102* | −0.022 | — | ||||

| 6. Trust in oneself | 0.094* | 0.009 | −0.048 | 0.019 | 0.011 | — | |||

| 7. Trust in others | 0.122** | −0.012 | −0.061 | 0.062 | −0.036 | −0.251** | — | ||

| 8. Distrust in others | −0.017 | 0.050 | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.181** | −0.022 | −0.251** | — | |

| 9. DAST-20 | −0.120** | −0.182** | 0.307** | 0.084* | 0.191** | −0.154** | −0.096* | 0.143** | — |

- Note: ACE = adverse childhood experience; DAST-20 = drug abuse screening test 20. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Subsequently, multiple regression analysis was performed. The results showed that trust in oneself (β = −0.144, p < 0.001) and distrust in others (β = 0.091, p < 0.05) had main effects on predicting the severity of drug dependence and that the effects of trust in oneself (β = 0.086, p < 0.05) and distrust in others (β = 0.088, p < 0.05) on the severity of drug dependence differed by gender (Table 3).

| B | SE B | β | t | Tolerance | VIF | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in oneself | |||||||

| Age | −0.047 | 0.023 | −0.111 | −2.056* | 0.535 | 1.868 | 0.175*** |

| First onset age | −0.040 | 0.024 | −0.072 | −1.640 | 0.806 | 1.240 | |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 0.113 | 0.018 | 0.260 | 6.406*** | 0.952 | 1.051 | |

| Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.429 | 0.110 | 0.200 | 3.912*** | 0.601 | 1.664 | |

| ACE score | 0.183 | 0.075 | 0.101 | 2.436* | 0.918 | 1.089 | |

| Trust in oneself | −0.185 | 0.052 | −0.144 | −3.545*** | 0.955 | 1.047 | |

| Trust in oneself × gender | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.086 | 2.059* | 0.902 | 1.108 | |

| Trust in others | |||||||

| Age | −0.053 | 0.023 | −0.125 | −2.282* | 0.532 | 1.878 | 0.159*** |

| First onset age | −0.040 | 0.025 | −0.071 | −1.597 | 0.801 | 1.249 | |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 0.114 | 0.018 | 0.264 | 6.451 | 0.953 | 1.050 | |

| Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.444 | 0.111 | 0.207 | 4.014 | 0.601 | 1.663 | |

| ACE score | 0.169 | 0.076 | 0.093 | 2.230* | 0.912 | 1.097 | |

| Trust in others | −0.063 | 0.047 | −0.054 | −1.336 | 0.963 | 1.039 | |

| Trust in others × gender | 0.051 | 0.026 | 0.082 | 1.954 | 0.917 | 1.090 | |

| Distrust in others | |||||||

| Age | −0.052 | 0.023 | −0.124 | −2.286* | 0.541 | 1.848 | 0.169*** |

| First onset age | −0.044 | 0.025 | −0.080 | −1.791 | 0.798 | 1.253 | |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 0.115 | 0.018 | 0.266 | 6.536 | 0.957 | 1.045 | |

| Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.440 | 0.110 | 0.205 | 3.993 | 0.599 | 1.669 | |

| ACE score | 0.139 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 1.826 | 0.896 | 1.116 | |

| Distrust in others | 0.078 | 0.036 | 0.091 | 2.191* | 0.918 | 1.089 | |

| Distrust in others × gender | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.088 | 2.073* | 0.873 | 1.146 |

- Note: Independent variables were trust in oneself, trust in others, and distrust in others; control variables were age, first onset age, stimulant use frequency per month, number of times incarcerated for drug use, ACE score, and interaction terms trust in oneself, trust in others, distrust in others scores and gender; dependent variable was drug abuse screening test 20 (DAST-20). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.3 Gender Differences of Relationship Between Trust and Severity of Drug Dependence

Since the results for all participants showed that the effect of trust on the severity of drug dependence differed by gender, we analyzed the relationship between trust and the severity of drug dependence separately for men and women. Prior to the multiple regression analysis, the correlation analysis was conducted between trust and the severity of drug dependence, separated by gender. Regarding the correlation coefficients between trust and the severity of drug dependence for men, the correlation coefficient between trust in oneself and the severity of drug dependence was r = −0.203 (p < 0.01), the correlation coefficient between trust in others and the severity of drug dependence was r = −0.126 (p < 0.05), and the correlation coefficient between distrust in others and the severity of drug dependence was r = 0.101 (p < 0.05). On the other hand, for women, the correlation coefficient between distrust in others and the severity of drug dependence was r = 0.189 (p < 0.01) (Table 4, Figures 4-7).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | 0.270** | −0.104* | 0.613** | −0.140** | 0.105* | 0.109* | 0.023 | −0.038 |

| 2. First onset age | 0.289** | — | −0.136** | −0.053 | −0.064 | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.080 | −0.116* |

| 3. Stimulant use frequency per month | −0.239** | −0.166* | — | −0.028 | 0.050 | −0.116* | −0.091 | 0.081 | 0.341** |

| 4. Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.469** | −0.224** | −0.019 | — | 0.033 | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.049 | 0.123* |

| 5. ACE score | −0.067 | −0.100 | 0.131 | −0.037 | — | 0.012 | −0.068 | 0.155** | 0.109* |

| 6. Trust in oneself | 0.066 | −0.042 | 0.076 | 0.042 | 0.021 | — | 0.556** | −0.010 | −0.203** |

| 7. Trust in others | 0.124 | −0.070 | 0.021 | 0.158* | 0.072 | 0.471** | — | −0.188** | −0.126* |

| 8. Distrust in others | −0.070 | 0.010 | −0.095 | −0.034 | 0.180* | −0.042 | −0.361** | — | 0.101* |

| 9. DAST-20 | −0.252** | −0.277** | 0.230** | 0.058 | 0.260** | −0.064 | −0.016 | 0.189** | — |

- Note: The vertical value is male and the horizontal value is female. Abbreviations: ACE, adverse childhood experience; DAST-20, drug abuse screening test 20. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Subsequently, multiple regression analysis was performed. The results showed that the model for men (see Table 5), that is trust including trust in oneself and others and distrust in others, accounted for 18% of the severity of drug dependence (R2 = 0.180, p < 0.001), which corresponded to Cohen's criteria [37] for between a medium and large effect. Trust in oneself for men was found to be an influencing factor for the severity of drug dependence (β = −0.183, p < 0.01; Table 5). In the model for women (see Table 6), trust explained 23% of the severity of drug dependence (R2 = 0.236, p < 0.001), which met the same Cohen's (1992) criteria as that for men. Additionally, trust in oneself and others for women was shown to be an influencing factor for the severity of drug dependence (β = 0.185, p < 0.05).

| B | SE B | β | t | Tolerance | VIF | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.016 | 0.026 | −0.043 | −0.633 | 0.516 | 1.940 | 0.180*** |

| First onset age | −0.024 | 0.029 | −0.044 | −0.824 | 0.824 | 1.213 | |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 0.133 | 0.021 | 0.309 | 6.283*** | 0.961 | 1.041 | |

| Number of times incarcerated for drug use | 0.332 | 0.120 | 0.176 | 2.771** | 0.574 | 1.742 | |

| ACE score | 0.097 | 0.092 | 0.052 | 1.051 | 0.937 | 1.068 | |

| Trust in oneself | −0.224 | 0.072 | −0.183 | −3.091** | 0.665 | 1.504 | |

| Trust in others | 0.045 | 0.066 | 0.041 | 0.687 | 0.652 | 1.535 | |

| Distrust in others | 0.058 | 0.041 | 0.071 | 1.421 | 0.931 | 1.075 |

- Note: Independent variables were trust in oneself, trust in others, and distrust in others; control variables were age, first onset age, stimulant use frequency per month, and number of times incarcerated for drug; dependent variable was the drug abuse screening test 20 (DAST-20). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

| B | SE B | β | t | Tolerance | VIF | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

−0.133 |

0.047 | −0.254 | −2.853** | 0.592 | 1.690 | 0.236*** |

| First onset age | −0.057 | 0.044 | −0.105 | −1.290 | 0.713 | 1.402 | |

| Stimulant use frequency per month | 0.070 | 0.032 | 0.161 | 2.212* | 0.886 | 1.128 | |

| Number of times incarcerated | 0.618 | 0.253 | 0.202 | 2.446* | 0.691 | 1.448 | |

| ACE score | 0.253 | 0.134 | 0.136 | 1.883 | 0.895 | 1.117 | |

| Trust in oneself | −0.175 | 0.110 | −0.127 | −1.598 | 0.742 | 1.347 | |

| Trust in others | 0.164 | 0.108 | 0.131 | 1.520 | 0.630 | 1.588 | |

| Distrust in others | 0.169 | 0.071 | 0.185 | 2.387* | 0.780 | 1.281 |

- Note: Independent variables were trust in oneself, trust in others, and distrust in others; control variables were age, first onset age, stimulant use frequency per month, and number of times incarcerated for drug use; dependent variable was the drug abuse screening test 20 (DAST-20). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

4 Discussion

This research was a secondary analysis of the original project titled, “Health survey for drug offenders 2017,” conducted by the Research and Training Institute, Ministry of Justice in Japan. More specifically, we investigated the effects of trust on the severity of drug dependence in a large national sample of incarcerated substance users. By comparing data from the stimulant offenders used in this study with those published by the Ministry of Justice, Shimane et al. [31] concluded that the representativeness of the participants in this study was acceptable. Therefore, we argue that the results of this study fully reflect the characteristics of stimulant offenders in Japan.

4.1 Clinical Characteristics of Participants

Men in this study had an average stimulant use frequency of 8.01 times per month, an average of three prison sentences for drug use, and an average DAST-20 score of 9.26, which corresponds to moderate severity. Women participants had an average stimulant use frequency of 9.99 times per month, an average of 2.38 times incarcerated for drug use, and an average DAST-20 score of 10.34, which indicates moderate severity as men's score. These DAST-20 scores are highly correlated with a diagnosis of drug abuse/dependence as defined in the DSM-III-R [38]. Furthermore, the guidelines for using the drug abuse screening test [39] state that when the DAST-20 score is six points or more, the respondent should receive outpatient treatment. Thus, both men and women participants in the present study would be unable to control their drug use and would potentially be diagnosed with substance use disorder.

4.2 The Effect of Trust on the Severity of Drug Dependence

In this study, multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for men and women, considering the fact that there were gender differences in the effect of the trust on the severity of drug dependence. Our findings indicate a gender difference in the effect of trust on the severity of drug dependence. More specifically, after controlling for confounding factors, we found that trust in oneself affected the severity of men's drug dependence. The scales used to assess trust in oneself included items such as “I can trust myself to some extent” and “I consider myself to be a trustworthy person”; items measuring self-control were also included, for example, “I feel like I can manage my own life” and “I can control my own behavior to some extent.” Therefore, we interpreted the results to mean that low trust in oneself—including low self-control—influences the severity of drug dependence. Given that substance use disorders are disorders of control [40], it can be argued that the men in this study (stimulant offenders) diminished trust in oneself through the decline of self-control regarding their drug use experience of “I know, but I can't stop.” As a result, they may have become desperate and exacerbated their severity of drug dependence. Gottfredson and Hirschi showed in their self-control theory that individual differences in criminal and deviant behavior can be explained by differences in the ability to control oneself in the face of temptation [41]. Indeed, previous studies have indicated that self-control associates with substance use [42], that poor self-control increases substance use [43], and that low self-control associates with methamphetamine use [44, 45]. These findings are consistent with our present findings; low esteem—including low self-control—affects the severity of drug use dependence. The present study was the first study to examine and discuss the relationship between trust in oneself including self-control or self-esteem and the severity of drug dependence among men who are stimulant offenders, thus our findings are of academic importance.

Meanwhile, after controlling for confounding factors, high levels of distrust in others influenced the severity of women's drug dependence severity. Women who use drugs experience more interpersonal conflict than men [46] and interpersonal conflict can be a risk factor for drug use and relapse [47, 48]. Additionally, a self-medication hypothesis was proposed, which posits that people with drug use disorders seek to stifle the pain caused by interpersonal relationships with drugs [13]; thus, our findings suggest that it may be useful to understand women who are stimulant offenders from the perspective of interpersonal relationship conflicts and self-medication hypotheses.

Taken together, our study has academic significance in that the present study has clarified the gender differences in the effect of trust on the severity of drug dependence among incarcerated individuals.

4.3 Clinical Implications

Based on our examination of the effect of trust on the severity of drug dependence, we suggest that it is important to provide support that considers gender differences in the treatment of stimulant offenders. For men, trust in oneself was shown to affect the severity of drug dependence. Given that sustained efforts to maintain abstinence over the long term require a sense of self-control that “I have the power to stay off drugs” [49], in relapse prevention programs for men who are stimulant offenders in penal institutions, affirming them through episodes when they did not use drugs, rather than only discussing episodes when they did use drugs, may be an effective way to encourage them to feel confident about stopping their drug use.

For women, our findings indicate that it is necessary to provide support that considers distrust of others. Particularly, women place more emphasis on relationships in their developmental process of social connections and intimacy than men [50], and therapeutic relationships account for more of the explained variance in treatment outcomes than any other variable [51]. For example, a perceived positive relationship with a therapist has been shown to influence a woman's decision to remain in substance user treatment [52]. Therefore, when supporting women who are substance users, it is important to develop and provide women-specific programs that focus on women-specific mental health and other issues [53-55]. Furthermore, a good therapeutic relationship between drug users and those who provide relapse-prevention support is a predictor of drug users' treatment commitment, retention, and treatment outcomes [56, 57], and building a trustful relationship with a counselor reportedly facilitates treatment [58]. Thus, it is important to take into account women's distrust in others and to carefully build a relationship of trust when supporting women stimulant offenders.

In sum, this study illustrated that increasing trust in oneself can be a protective factor for men who are stimulant offenders, while considering distrust in others and carefully building therapeutic relationship can be protective for women who are stimulant offenders. Therefore, our findings are also of clinical significance.

5 Limitations and Future Research

Several methodological limitations in this study should be mentioned. First, the survey was a self-administered questionnaire. As the survey items were related to prisoners' drug use, the possibility of social desirability impacting responses cannot be denied. Second, we used a cross-sectional study design, which does not provide evidence of causation. The hypothesis of this study assumes that trust influences the severity of drug dependence; therefore, trust should be treated as an antecedent factor. However, a causal relationship between trust and the severity of drug dependence cannot be inferred because the present study participants were not evaluated longitudinally. Therefore, the interpretation of the results and generalization of the findings should be made with caution. Finally, because the present study analyzed only prison inmates, caution is required when applying the findings to other stimulant users. Therefore, future research should use a longitudinal study design that does not rely solely on self-report and should include community samples of stimulant users with no imprisonment history.

6 Conclusion

This study clarified gender differences in the effect of trust on the severity of drug dependence, using data from stimulant offenders imprisoned throughout Japan. Our findings indicate that men's sense of trust in oneself negatively influenced the drug dependence severity. Therefore, when providing treatment programs, hopeful emphasis on their ability to stop using drugs may be effective, for example, focusing on their thinking and behaviors on the day they were able to resist using drugs. Additionally, women's sense of distrust in others negatively affects the severity of their drug dependence. Thus, it is necessary to consider their distrust in others and to carefully build a trusting relationship with them and provide support for them. These findings offer important contributions to the academic and clinical practice for programs and interventions that provide support for drug addiction and prevention of recidivism among stimulant offenders.

Author Contributions

S.O. designed this study, contributed to conduct statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript, T.S. obtained the grant for this survey to complete the final manuscript, Y.T., A.K., M.K., M.T., M.O., A.K., and T.M. supervised S.O. to complete the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We take this opportunity to express our appreciation to Dr. Taichi Okumura of Shiga University for his useful advice on the statistical analysis of this study.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan (approval number: A2017–107).

Consent

The cover of the questionnaire clearly stated that the survey was being conducted to help support people suffering from drug problems, that participation in the survey was voluntary and there would be no disadvantage for not participating in the survey, so participants were guaranteed the right to refuse to participate in the survey, that the survey would be anonymous and that the collected information would be processed statistically so that individuals would not be identified, and that personal information would not be leaked to external parties. In addition, a checkbox was provided on the cover of the questionnaire to confirm whether or not respondents agreed to answer the questionnaire, and respondents' intentions were confirmed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

- Those who can analyze this data are restricted to the investigators belonging to the Research and Training Institute of Justice, Ministry of Justice, and the co-investigators designated by the principal investigator at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, under the collaborative research agreement between the Research and Training Institute of Justice, Ministry of Justice and the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

- Those who can analyze this data are restricted to the co-investigators designated by the principal investigator at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, and besides, the secondary use of this data and information and the provision of them to other institutions to other institutions are prohibited, under the study protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan (approval number: A2017–107).

Please contact the first author regarding the data from this study.