Bioinformatic survey of CRISPR loci across 15 Serratia species

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR–Cas) system of prokaryotes is an adaptative immune defense mechanism to protect themselves from invading genetic elements (e.g., phages and plasmids). Studies that describe the genetic organization of these prokaryotic systems have mainly reported on the Enterobacteriaceae family (now reorganized within the order of Enterobacterales). For some genera, data on CRISPR–Cas systems remain poor, as in the case of Serratia (now part of the Yersiniaceae family) where data are limited to a few genomes of the species marcescens. This study describes the detection, in silico, of CRISPR loci in 146 Serratia complete genomes and 336 high-quality assemblies available for the species ficaria, fonticola, grimesii, inhibens, liquefaciens, marcescens, nematodiphila, odorifera, oryzae, plymuthica, proteomaculans, quinivorans, rubidaea, symbiotica, and ureilytica. Apart from subtypes I-E and I-F1 which had previously been identified in marcescens, we report that of I-C and the I-E unique locus 1, I-E*, and I-F1 unique locus 1. Analysis of the genomic contexts for CRISPR loci revealed mdtN-phnP as the region mostly shared (grimesii, inhibens, marcescens, nematodiphila, plymuthica, rubidaea, and Serratia sp.). Three new contexts detected in genomes of rubidaea and fonticola (puu genes-mnmA) and rubidaea (osmE-soxG and ampC-yebZ) were also found. The plasmid and/or phage origin of spacers was also established.

1 INTRODUCTION

The prokaryotic system Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR–Cas) is a defense mechanism for bacteria and archaea against the invasion of bacteriophages and selfish genetic elements such as plasmids. Since their discovery around 15 years ago (Bolotin et al., 2005; Makarova et al., 2006; Mojica et al., 2005), CRISPR–Cas systems have been the object of many studies and functions, other than adaptative immunity, as regulation of bacteria virulence and stress response have been reported (Faure et al., 2019; Louwen et al., 2014). Based on a census of complete genomes, it is now reckoned that these systems are distributed mainly in archaea (~82.5%) and, to a lesser extent, bacteria (~40%) (Makarova et al., 2020). The CRISPR-–Cas systems are composed of CRISPR arrays and adjacent CRISPR-associated (cas) genes. The former are composed of direct repeats interspaced by spacers; the latter encode proteins involved in the immune response and DNA repair. This ever-expanding knowledge of the composition and architecture of cas gene clusters has led to an updated classification of CRISPR–Cas systems where two classes, six types, and various subtypes (some of which are further divided into different variants) are now reported (Koonin & Makarova, 2017; Makarova et al., 2020). Class 1 includes the types I (DNA targeting), III (DNA and/or RNA targeting), and IV (DNA targeting), which are divided into seven subtypes I (A–G), six subtypes III (A–F), and three subtypes IV (A–C), respectively. Class 2 includes the types II (DNA targeting), V (DNA or RNA targeting), and VI (RNA targeting); they are also divided into subtypes: three subtypes II (A–C), eleven subtypes V (A–K and U), and four subtypes VI (A–D), respectively (Koonin & Makarova, 2017; Makarova et al., 2020). While Class 2 is found mainly in Bacteria, Class 1 is present both in Bacteria and Archaea. Studies on CRISPR–Cas systems have been performed on genomes of different bacteria families, with that of the Enterobacteriaceae being one of the most investigated (Medina-Aparicio et al., 2018; Shariat & Dudley, 2014; Xue & Sashital, 2019). This family was unique in the Enterobacterales order until 2016 when Adeolu et al. (2016) reclassified the order by adding six new families (Budviciaceae, Erwiniaceae, Hafniaceae, Morganellaceae, Pectobacteriaceae, Yersiniaceae). Despite this reclassification, data on CRISPR–Cas systems remain mainly limited to genera of the Enterobacteriaceae family (Díez-Villaseñor et al., 2010; Shariat et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016).

The genus Serratia, a Gram-negative rod, is now part of the family Yersiniaceae. Serratia species can be found in different environments (e.g., water, soil) and hosts (e.g., humans, insects, plants, vertebrates) where they may play different roles ranging from opportunistic pathogens to symbionts (Cristina et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2021; Lo et al., 2016). Among Serratia species, marcescens is undoubtedly the most studied mainly for its role played as a symbiont associated with insects and nematodes (Chen et al., 2017) or as a human opportunistic pathogen (currently reported as one of the most important bacteria responsible for acquired hospital infections such as bacteremia, pneumonia, intravenous catheter-associated infections, and endocarditis) (Ferreira et al., 2020). Other Serratia species responsible (to a minor extent) for human bacteremia are liquefaciens and odorifera (Mahlen, 2011). A growing number of marcescens genomes have then been sequenced with a pangenome allele database available for different studies ranging from virulence and antibiotic resistance to the identification of CRISPR systems (Abreo & Altier, 2019). A number of studies, in addition to marcescens, have also been reported for other Serratia species that play different roles in human and insect pathogenesis(Petersen & Tisa, 2013). Although the characterization of CRISPR systems represents a valuable substrate for diagnostic, epidemiologic, and evolutionary analyses (Louwen et al., 2014), data on CRISPR–Cas systems in the genus are scarce and limited to the detection of subtypes I-E and I-F1 in genomes of the species marcescens (Medina-Aparicio et al., 2018; Scrascia et al., 2019; Srinivasan & Rajamohan, 2019; Vicente et al., 2016).

In this study, 146 Serratia complete genomes and 336 high-quality assemblies are available for the species ficaria, fonticola, grimesii, inhibens, liquefaciens, marcescens, nematodiphila, odorifera, oryzae, plymuthica, proteomaculans, quinivorans, rubidaea, symbiotica, and ureilytica were explored for the presence and type of cas gene clusters and/or CRISPRs. Apart from subtypes I-E and I-F1, the study showed the presence (first detected in Serratia) of subtype I-C, the presence of unique loci, and detailed genomic contexts of CRISPR loci. The plasmid and/or phage origin of spacers was also assessed.

The discovery of CRISPR–Cas systems has allowed the development of new technology tools in the bioengineering field (Dong et al., 2021). A clear example is represented by gene editing strategies based on CRISPR/Cas9 technique successfully used in agriculture, nutrition, and human health (Nidhi et al., 2021). The development of new CRISPR-based applications also relies on the continuous update of CRISPR–Cas systems data and knowledge. Our study, in providing more comprehensive data on CRISPR loci in Serratia, has undoubtedly contributed to an expanded knowledge of these systems.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Genomes analyzed

One hundred and forty-six Serratia complete genomes were considered in this study. The set of genomes encompasses the 15 S. marcescens complete genomes we previously analyzed (Scrascia et al., 2019) and those of the genus Serratia available at the CRISPR–Cas++ database (https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/MainDb/StrainList) up to December 12, 2020 (Couvin et al., 2018; Pourcel et al., 2020) (Supporting Information: Table S1). Among genome sequences available at the assembly level of scaffolds or contigs available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly) up to December 12, 2020, we selected the high-quality assemblies (N50 > 50 kb, i.e. 50% of the entire assembly is contained in contigs or scaffolds equal to or larger than the 50 kb) that have been included in the study.

Species attribution and strain details (name, place, date of isolation) were recovered (when available) from GenBank or related articles. Serratia strains AS12 (NC_015566.1), FGI94 (NC_020064), FS14 (NZ_CP005927), SCBI (NZ_CP003424), YD25 (NZ_CP016948), and DSM21420 (GCA_000738675) were reclassified as reported by Sandner-Miranda et al. (2018), Sandner-Miranda et al. (2018). In the study reported by Sandner-Miranda et al., the strain ATCC39006 was not assigned to the genus Serratia and we did not include it in this study.

We also included sequences with the accessions MK507743, MK507744, MK507745, and MK507746 referring to contigs (N50 ranging from 228817 to 291462) harboring CRISPR loci in genome assemblies (unpublished) of four S. marcescens strains reported as secondary symbionts in the Red Palm Weevil (RPW) Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier, 1790) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Scrascia et al., 2016, 2019) (Supporting Information: Table S1), an alien invasive pest now threatening South America (Dalbon et al., 2021).

2.2 Detection of CRISPR–Cas loci

Details about the detection of a cas gene cluster with associated arrays (CRISPR–Cas system) and CRISPR arrays only for complete genomes were retrieved from the CRISPR–Cas++ database. CRISPR arrays recorded by CRISPR–Cas++ were assigned to Levels 1–4 based on the criteria required to select the minimal structure of putative CRISPR as reported by Pourcel et al. (2020). Level 1 is the lowest level of confidence. Levels 2–4 were assigned based on the conservation of repeats (which must be high in a real CRISPR) and on the similarity of spacers (it must be low). Level 4 CRISPRs were defined as the most reliable ones. Levels 1–3 may correspond to false CRISPRs. In our study, only CRISPRs recorded with Level 4, were considered. CRISPRs without a set of cas genes in the host genome were defined as “orphans.” Genomes harboring cas gene clusters were then submitted to the CRISPRone analysis suite (http://omics.informatics.indiana.edu/CRISPRone/) (Zhang & Ye, 2017) to graphically visualize the architecture of each cluster. The same suite was used to search and visualize cas gene clusters in the high-quality assemblies. A subtype of cas gene clusters was assigned according to the recent classification update for CRISPR–Cas systems (Makarova et al., 2020).

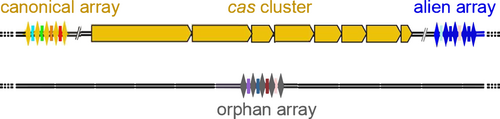

2.3 In silico analyses of consensus of direct repeats

A consensus of direct repeats from CRISPRs was clustered by BLAST similarity. Some consensus DRs were manually trimmed when just a few terminal nucleotides were the only difference from the other members of the same cluster. The consensus DRs were used as input for CRISPRBank (http://crispr.otago.ac.nz/CRISPRBank/index.html) and CRISPR–Cas++ to assign, based on identity with known consensus DRs (Biswas et al., 2016; Couvin et al., 2018; Pourcel et al., 2020), a specific CDR type to CRISPR. The CRISPRs whose CDR type was consistent with the subtype of the cas gene set harbored in the same genome were defined as “canonical.” While those not consistent with the subtype of the cas gene set harbored in the same genome were defined as “alien.” A schematic diagram of alien, canonical and orphan arrays is shown in Figure 1. consensus DRs and the number of repeats of the CRISPRs in the high-quality assemblies of Serratia sp. strains DD3, Ag1, and Ag2 were recovered from the CRISPRone output. Spacers’ analysis for duplications (spacers of Ag1, Ag2, and DD3 included) was performed through the CRISPRCasdb spacer database at the CRISPRCas++ site (https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/MainDbQry/Index). Phagic and/or plasmidic origin of matching protospacers were searched at the CRISPRTarget site (http://crispr.otago.ac.nz/CRISPRTarget/crispr_analysis.html) (Biswas et al., 2016).

2.4 Genomic contexts of CRISPR-positive genomes

Analysis of CRISPR-positive complete genomes and high-quality assemblies was performed to better characterize the genomic context surrounding the cas gene sets and/or CRISPR arrays. High-quality assemblies with at least 4 kb flanking the cas gene sets were considered. These regions were annotated by Prokka (https://github.com/tseemann/prokka) (Seemann, 2014). Synteny was established by either the Mauve algorithm (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html) (Darling et al., 2010) or visual inspection of annotated proteins.

2.5 Phylogenetic analyses

The evolutionary relationship of Serratia strains found positive for cas genes sets was established and graphically depicted by the Cas3 sequence tree. All the protein sequences were aligned by the MUSCLE algorithm (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/) (Edgar, 2004a, 2004b). The 16S rRNA gene tree was also drawn for comparison. Dendrograms were generated by the Neighbor-Joining clustering method and average distance trees with JalView (https://www.jalview.org/) (Waterhouse et al., 2009). For the 16S rRNA gene tree, the multiple sequence alignment was obtained by retrieving from one to seven full gene sequences (complete genomes) or truncated 16S rRNA gene sequences (high-quality assemblies). A phylogenetic tree was obtained by multiple alignment of all retrieved 16S rRNA genes; an abbreviated tree was constructed by using one sequence from each genome.

3 RESULTS

3.1 CRISPR-positive genomes

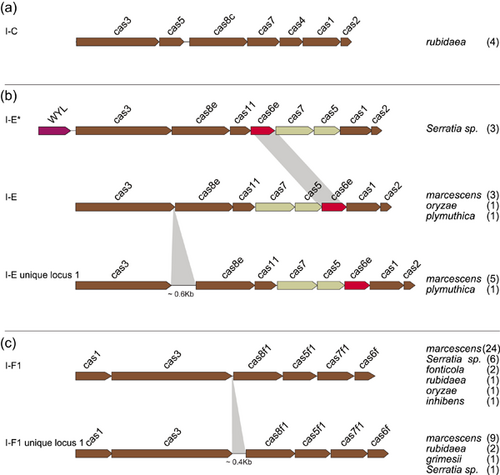

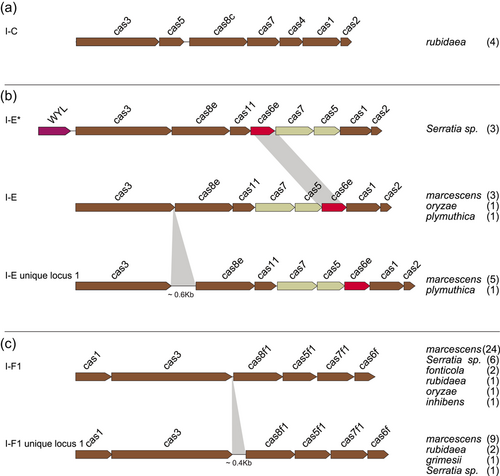

A collection of 146 Serratia complete genomes was explored for the presence of cas gene clusters and/or CRISPR arrays. Most of the genomes (134) were reported as known species: ficaria (1), fonticola (7), grimesii (1), inhibens (1), liquefaciens (7), marcescens (87), nematodiphila (1), plymuthica (11), proteomaculans (2), quinivorans (2), rubidaea (8), symbiotica (4), ureilytica (2). The remaining 12 genomes were of unidentified species and, from here on, they will be referred to as Serratia sp. (Supporting Information: Table S1). The CRISPR–Cas systems or only CRISPR arrays (orphan array) were detected in 35 complete genomes (24%) of which 17 harbored a CRISPR–Cas system, while 18 harbored orphan arrays. Some complete genomes characterized by the same cas gene set subtype and identical numbers of both CRISPRs and spacers were assumed as multiple records of the same genome (Table 1). All detected cas gene clusters were of Class 1. Nine were identical to those already published (Makarova et al., 2020) and distributed as follows: two subtypes I-C (rubidaea) (Figure 2a), one I-E (plymuthica) and six I-F1 (1 fonticola, 3 marcescens, 1 inhibens, and 1 rubidaea) (Figure 2b,c). The remaining eight clusters were found atypical and assigned, in this study, to I-E unique locus 1 (3 marcescens and 1 plymuthica) and I-F1 unique locus 1 (1 marcescens, 2 rubidaea, and 1 Serratia sp.).

| Subtype of cas cluster | CRISPRs | Serratia species | Strain | Source | Place of isolation | Year of isolation | Accession/Assembly | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR type | Category | #Arrays (#spacers) | |||||||

| I-C | I-C | Canonical | 1 (14) | rubidaea | FDAARGOS_926a | N/A | N/A | N/A | NZ_CP065640.1 |

| I-E | Alien | 1 (7) | |||||||

| I-F | Alien | 2 (2, 5) | |||||||

| I-C | I-C | Canonical | 1 (14) | rubidaea | NCTC12971a | N/A | N/A | N/A | LR590463.1 |

| I-E | Alien | 1 (7) | |||||||

| I-F | Alien | 2 (2, 5) | |||||||

| I-E | I-E | Canonical | 2 (43, 30) | plymuthica | NCTC8900 | N/A | N/A | N/A | LR134151.1 |

| I-E unique locus 1 | I-E | Canonical | 4 (6, 8, 27, 44) | marcescens | E28 | Hospital Ensuite | Australia | 2012 | CP042512.1 |

| “ | I-E | Canonical | 3 (7, 10, 22) | marcescens | SER00094 | Clinical | United States | 2017 | CP050447.1 |

| “ | I-E | Canonical | 3 (11, 39, 69) | marcescens | MSB1_9C-sc-2280320 | N/A | N/A | N/A | LR890657.1 |

| “ | I-E | Canonical | 2 (35, 47) | plymuthica | NCTC8015 | Canal water | N/A | N/A | LR134478.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 2 (25, 27) | marcescens | 12TM | Pharyngeal secretions | Romania | 2014 | CM008894.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 2 (8, 17) | marcescens | N4-5 | Soil | United States | 1995 | CP031316.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 2 (6, 45) | marcescens | PWN146 | Bursaphelenchus xylophilus | Portugal | 2010 | LT575490.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 3 (11, 13, 42) | fonticola | DSM 4576 | Water | N/A | 1979 | NZ_CP011254.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 2 (15, 24) | inhibens | PRI-2c | Maize rhizosphere soil | The Netherlands | 2004 | NZ_CP015613.1 |

| I-F1 | I-F | Canonical | 6 (1, 3, 7, 7, 14, 14) | rubidaea | FDAARGOS_880 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CP065717.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | I-F | Canonical | 3 (5, 10, 29) | marcescens | FZSF02 | soil | China | 2014 | CP053286 |

| “ | I-E | Alien | 1 (9) | rubidaea | FGI94 | Atta colombica | Panama | 2009 | NC_020064.1; |

| I-F | Canonical | 3 (6, 15, 16) | CP003942 | ||||||

| “ | I-F | Canonical | 4 (3, 6, 7, 8) | rubidaea | NCTC10036 | Finger | N/A | N/A | LR134493.1 |

| I-E | Alien | 1 (3) | |||||||

| “ | I-F | Canonical | 4 (2, 2, 7, 7, 10) | Serratia sp. | JUb9 | Compost | France | 2019 | CP060416.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (21) | marcescens | SCQ1 | Blood from silkworm | China | 2009 | CP063354.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (3) | marcescens | AR_0130 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CP028947.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (6) | plymuthica | AS9b | Plant | Sweden | N/A | NC_015567.1; CP002773.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (6) | plymuthica | AS12b | Plant | Sweden | 1998 | NC_015566.1; CP002774 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (6) | plymuthica | AS13b | Plant | Sweden | N/A | NC_017573.1; CP002775 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (3) | marcescens | B3R3 | Zea mays | China | 2011 | NZ_CP013046.2 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 2 (1, 2) | Serratia sp. | MYb239 | Compost | Germany | N/A | CP023268.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (3) | Serratia sp. | SSNIH1 | N/A | United States | 2015 | CP026383.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (3) | nematodiphila | DH-S01 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CP038662.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 2 (4, 6) | rubidaea | NCTC9419 | N/A | N/A | N/A | LR134155.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 2 (6, 2) | rubidaea | NCTC10848 | N/A | N/A | N/A | LS483492.1 |

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 1 (3) | ||||||

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 1 (26) | marcescens | KS10c | Marine | United States | 2006 | CP027798.1 |

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 1 (26) | marcescens | EL1c | Marine | United States | 2002 | CP027796.1 |

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 2 (3, 32) | marcescens | CAV1761d | Peri-rectal | Virginia | 2014 | CP029449.1 |

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 2 (3, 32) | marcescens | CAV1492d | Clinical | United States | 2011–2012 | NZ_CP011642.1 |

| N/A | I-E | Orphan | 1 (2) | Serratia sp. | KUDC3025 | Rhizospheric soil | South Korea | 2017 | CP041764.1 |

| N/A | I-F | Orphan | 1 (2) | plymuthica | V4 | Milk processing plant | Portugal | 2006 | CP007439.1 |

| N/A | I-C | Orphan | 1 (8) | symbiotica | CWBI-2.3 | Aphis fabae (type strain of S. symbiotica) | Belgium | 2009 | CP050855.1 |

- Abbreviations: CDR, consensus DR; CRISPR– Cas, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins.

- a,b,c,d Possible multiple records of the same genome.

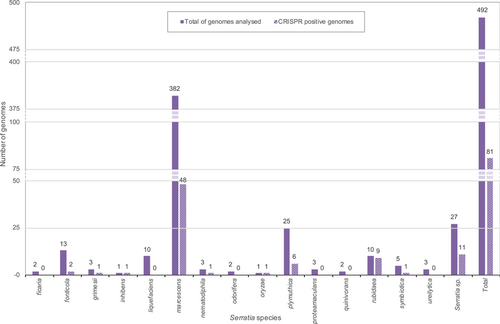

The I-E unique locus 1 had the cas3-cas8e genes spaced by ~600 nt while the I-F1 unique locus 1 had the cas3-cas8f1 genes separated from each other by ~400 nt (Figure 2b,c). Since the I-E unique locus 1 and the I-F1 unique locus 1 cas gene clusters have never been reported in Serratia, their presence was further explored among 336 Serratia high-quality assemblies. The assemblies were distributed as follows: ficaria (1), fonticola (6), grimesii (2), liquefaciens (3), marcescens (295), nematodiphila (2), odorifera (2), oryzae (1), plymuthica (4), proteomaculas (1), rubidaea (2), symbiotica (1), ureilytica (1), and Serratia sp. (15) (Supporting Information: Table S1). Of the 336 analyzed genomes, 46 (13.7%) were positive for the presence of cas gene clusters. Twenty-six were subtype I-F1 (21 marcescens, one fonticola, and 4 Serratia sp.) (Figure 2c), two subtype I-C (rubidaea) (Figure 2a), and three subtype I-E (marcescens) (Figure 2b; Table A1). The I-E unique locus 1 was detected in two genomes of marcescens, the I-F1 unique locus 1 in eight genomes of marcescens, and one of grimesii. In three genomes of Serratia sp. (strains Ag1, Ag2, and DD3) an additional unique locus of the subtype I-E, identical to I-E* previously reported by Shen et al. (2017), was detected (Figure 2b). The locus I-E* identified in this study was characterized by the translocation of cas6e between cas7 and cas11, and the presence (upstream of cas3) of a gene harboring the WYL domain which encodes for a potential functional partner of the CARF (CRISPR–Cas Associated Rossmann Fold) superfamily proteins (Makarova et al., 2020). Proteins containing the WYL domain (name standing for the three conserved amino acids tryptophan, tyrosine, and leucine, respectively) have only been reported for subtypes I-D and VI-D (Makarova et al., 2014, 2019). The distribution of CRISPR-positive genomes, over the total analyzed, among Serratia species is shown in Figure 3. Coexistence in the same genome of different sets of cas genes was also detected: subtypes I-E and I-F1 were found in the single HQA of oryzae, while I-E* and I-F1were detected in two high-quality assemblies of Serratia sp. (strains Ag1 and Ag2) (Table A1).

3.2 Consensus DRs and spacers

The 35 CRISPR-positive complete genomes harbored 78 CRISPRs of which 48 were canonical. The latter were distributed as follows: fonticola (4), inhibens (1), marcescens (19), plymuthica (5), rubidaea (15), and Serratia sp. (4). Twenty-three arrays were orphans and detected in genomes of marcescens (8), plymuthica (4), symbiotica (1), nematodiphila (1), rubidaea (5), and Serratia sp. (4) (Table 1; Figure 1). Alien arrays (8) were only detected in the species rubidaea. For a comprehensive analysis, arrays in the three high-quality assemblies Ag1, Ag2, and DD3 were included (Table A1). All disclosed CRISPRs were assigned, by comparative sequence analyses, to consensus DR types I-C, I-E, or I-F (Table 1). The association between consensus DR types and cas gene sets (canonical and unique loci) is reported in Table 2. Based on their nucleotide identity, the consensus DRs identified for subtype I-E and its unique loci (I-E* and unique locus 1) could be arranged into two clusters named consensus DR-I and consensus DR-II. consensus DR-I was composed of 6 consensus DRs (identity from 83% to 96%) and linked to the cas gene sets I-E and I-E unique locus 1. consensus DR-II was composed of 2 consensus DRs (identity of about 96%) and linked to the cas gene set I-E*. When the consensus DRs of the two clusters were compared to each other, the nucleotide identity dropped to 55%–62%.

| Sequence (5'−3') | # nt | Record in CRISPRBank and CRISPR–Cas++ | CDRa type | Associated cas genes set(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTCGTGCCTCATGCAGGCACGTGGATTGAAAC | 32 | I-C | I-C | I-C |

| GTCGTGCCTCACGTAGGCACGTGGATTGAAA | 31 | I-C | I-C | I-C |

| CGGTTCATCCCCGCTGGCGCGGGGAATAGa,d | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E |

| CGGTTTATCCCCGCTCTCGCGGGGAACACa | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E; I-E unique locus 1 |

| CGGTTTATCCCCGCTGACGCGGGGAACACa | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E unique locus 1 |

| CGGTTTATCCCCGCTGGCGCGGGGAACACa | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E; I-E unique locus 1 |

| CGGTTTATCCCCGCTCGCGCGGGGAACACa | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E |

| CGGTTTATCCCCGCTAGCGCGGGGAACACa | 29 | I-E | I-E | I-E |

| GAAACACCCCCACGTGCGTGGGGAAGACb,c | 28 | I-E | I-E* | I-E* |

| GAAACACCCCCACGTGCGTGGGGAAGGCd,c | 28 | I-E | I-E* | I-E* |

| GTGCACTGCCGTACAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1; I-F1 unique locus 1 |

| GTTCACTGCCGCATAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1 |

| GTTCACTGCCGTGCAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1 |

| GTTCACTGCCGTATAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1 |

| GTTCGCTGCCGTGCAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1 |

| GTTCACTGCCGTACAGGCAGCTTAGAAA | 28 | I-F | I-F | I-F1 |

- Note: Palindrome identified in each consensus DR is underlined.

- Abbreviation: CDR, consensus DR.

- a Consensus DR-I group.

- b Consensus DR associated with the 20DRs array in Ag1 strain, the 3DRs array in Ag2 strain and the DD3 arrays (Table A1).

- c Consensus DR-II group.

- d Consensus DR associated with the 5DRs arrays in Ag1 and Ag2 strains (Table A1).

The architecture of the cas gene set I-E* has previously been reported for Klebsiella and Vibrio cholerae (I-E variant) (McDonald et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2017). We then compared the consensus DRs sequences I-E* and I-E variant with those of consensus DR-II and the identity was found between 82% and 96%. This association has further been confirmed by results obtained from the analysis of the cas gene clusters identified in 99 genomes retrieved from CRISPRBank and by searching for the presence of consensus DRs I-E*. Results showed that 95 of these genomes had a cas gene architecture identical to that of I-E*. The remaining four genomes harbored a truncated set of cas genes. Overall these data linked specifically consensus DR-II to the cas gene set I-E*.

A total of 1391 spacers were identified. Identical arrays were shared by rubidaea strains FDAARGOS_926 and NCTC12971. Likewise, different sets of identical arrays were shared by plymuthica strains AS9, AS12, and AS13; marcescens strains KS10 and EL1; marcescens strains CAV1761 and CAV1492 (Supporting Information: Table S2). These findings confirmed multiple records of the same genome for each group of strains and the total number of spacers was estimated at 1290 of which 1219 were unique and 330 matched protospacers with the following origin: 131 phages, 132 plasmids, and 67 phage/plasmid (Supporting Information: Table S2).

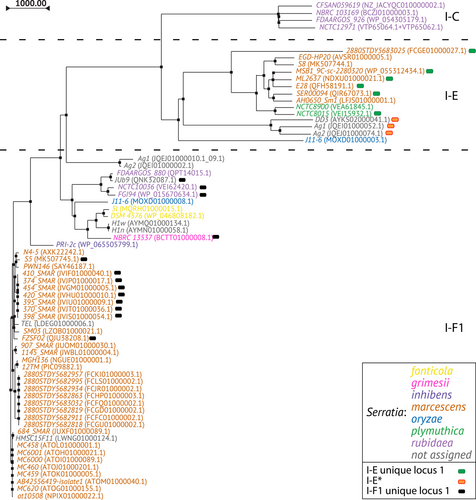

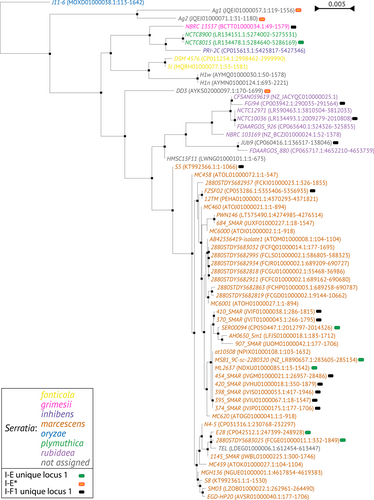

3.3 Phylogenetic trees

The phylogenetic tree generated by multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences of Cas3 showed a clusterization of the subtypes I-C, I-E, and I-F1 into three distinct branches (Figure 4). The I-E unique locus 1 and I-F1 unique locus 1 were randomly distributed among the I-E and I-F1, respectively, while the I-E* appears in a group within a sub-lineage of I-E. Within the I-C, I-E, and I-F1 branches, strains from the same species are grouped together. The phylogenetic tree based on multiple alignment of the 16S rRNA gene sequences was generated for comparison (Figure 5 and Supporting Information: Figure S1). The 16S rRNA gene trees showed, as expected, a nesting of the strains from the same species. The phylogenetic distribution of Serratia species in the Cas3 tree may suggest a possible independent intra-species evolutionary pathway. However, because the number of available CRISPR-positive genomes is too low for most Serratia species such a hypothesis needs to be validated by future studies. The position of strains TEL in the cluster marcescens and JUb9 in the cluster rubidaea shown in the Cas3 phylogenetic tree was confirmed by the 16S rRNA gene tree, which might suggest a species assignment for these strains.

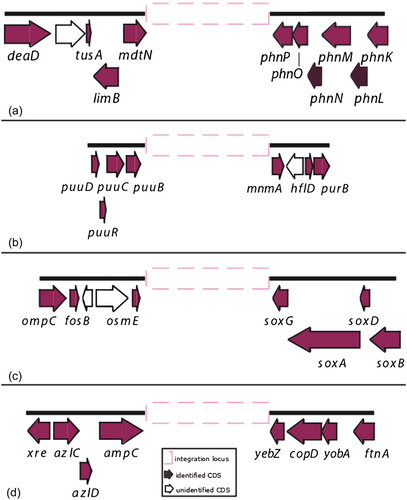

3.4 CRISPR genomic contexts

The 35 CRISPR-positive complete genomes and 28 of the 46 CRISPR-positive high-quality assemblies were analyzed to identify possible shared genomic contexts. Eight different genomic contexts, named from A to H, were identified. Contexts A to D (Figure 6) were shared by different genomes, while those from E to H were identified in single genomes. The genomic context A (mdtN-phnP) has previously been described in S. marcescens strains isolated as a secondary symbiont of RPW and in other marcescens complete genomes available in the NCBI database (Scrascia et al., 2019) becoming the most commonly shared in this study being identified in 55 genomes distributed as follows: 35 marcescens, one grimesii, one inhibens, one nematodiphila, six plymuthica, six rubidaea, and five Serratia sp. Contexts B (puu genes-mnmA), C (osmE-soxG), and D (ampC-yebZ) were shared by 11, four, and six genomes, respectively; context B by genomes of species fonticola (2), rubidaea (7), and Serratia sp. (2); C and D only by rubidaea genomes. For context D, assignment to rubidaea was assumed for the strain JUb9 (see above). The contexts E (nrdG-bglH) and F (sucD-vasK) were both identified in the single genome of S. oryzae strain J11-6; while G (gntR-cda) and H (gutQ-queA) in genomes of the Serratia sp. Ag1 and S. symbiotica CWBI-2.3, respectively (Table 3). Distribution of the genomic contexts by subtypes of cas gene sets and/or consensus DR types is reported in Table A2. Genomes of species rubidaea were characterized by the presence of multiple CRISPR contexts (A, B, C, D) with the context C associated with the cas gene set of subtype I-C.

| Genomic context | Chromosomal region | Species (#genomes) | Strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | mdtN-phnP | marcescens (35) | E28; S5; S8; B3R3; PWN146; CAV1492; 12TM; 2880STDY5682818; 2880STDY5682863; AH0650_Sm1; AR_0130; CAV1761; EGD-HP20; EL1; FZSF02; KS10; MC459; 2880STDY5682911; 2880STDY5683032; 2880STDY5682819; 2880STDY5682934; 2880STDY5682957; 2880STDY5682995; 454_SMAR; 420_SMAR; 395_SMAR; 370_SMAR; 1145_SMAR; MSB1_9C-sc-2280320; N4-5; SER00094; SCQ1; SM03; MGH136; at10508; |

| grimesii (1) | NBRC 13537 | ||

| inhibens (1) | PRI-2c | ||

| nematodiphila (1) | DH-S01 | ||

| plymuthica (6) | AS9; AS12; AS13; NCTC8015; NCTC8900; V4 | ||

| Unknown (5) | TEL; SSNIH1; KUDC3025; MYb239; JUb9 | ||

| rubidaea (6) | FGI94; NCTC10848; FDAARGOS_880; NCTC10036; NCTC12971; FDAARGOS_926 | ||

| B | puu genes-mnmA | fonticola (2) | DSM 4576; 5 l |

| rubidaea (7) | NCTC10848; FDAARGOS_880; NCTC9419; NCTC10036; NCTC12971; FDAARGOS_926; FGI94 | ||

| Unknown (2) | JUb9; MYb239 | ||

| C | osmE-soxG | rubidaea (4) | NBRC 103169; CFSAN059619; NCTC12971; FDAARGOS_926 |

| D | ampC-yebZ | rubidaea (5) | FDAARGOS_926; NCTC12971; NCTC10036; NCTC9419; FDAARGOS_880; |

| Unknown (1) | JUb9 | ||

| E | nrdG-bglH | oryzae (1) | J11-6 |

| F | sucD-vasK | ||

| G | gntR-cda | Unknown (1) | Ag1 |

| H | gutQ-queA | symbiotica (1) | CWBI-2.3 |

4 DISCUSSION

Bacteria of the genus Serratia are ubiquitous and have been isolated from soil, water, plant roots, insects, and the gastrointestinal tract of animals (Cristina et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2021; Lo et al., 2016). This broad range of environments exposes Serratia strains to exogenous genetic elements such as plasmids, phages, and chromosomal fragments of other bacteria. Some of them may represent a life threat (e.g., phages) or a metabolic burden (e.g., plasmids) to which CRISPR–Cas systems represent a unique adaptative immunity defense mechanism. Studying the presence/absence of CRISPR–Cas systems and their features in different genera of families is a relatively new scientific approach to investigation to gain data on the evolution of these systems and their role played during the bacterial lifetime (Butiuc-Keul et al., 2022). The average percentage of CRISPR distribution among Bacteria is the outcome of processes and/or factors that play different ecological roles within a genus/species. Among these processes/factors are noteworthy the balance between protection provided by CRISPR systems and their possible deleterious effects (e.g., self-targeting spacers), the role played by exogenous genetic elements (e.g., plasmids, phages, etc.) in bacteria evolution and the horizontal transfer of CRISPR systems.

Data on CRISPR loci in Serratia are limited to complete genomes of S. marcescens strains (Medina-Aparicio et al., 2018; Scrascia et al., 2019; Srinivasan & Rajamohan, 2019; Vicente et al., 2016). In the present study, along with the species marcescens, we extended data on CRISPR loci to 14 additional Serratia species. Note, CRISPRs were detected in 24% of the complete genomes and about 14% of the high-quality assemblies analyzed. The percentage of detection is lower than that reported for Bacteria (about 40%) (Makarova et al., 2020). However, whether the lower percentage of detection in Serratia reflects a distinguishing feature of the genus (particularly for the most representative analyzed marcescens species where the percentage was 12.6%) or a misrepresentative distribution of the available genomes in databases, remains to be established.

Most of the loci identified in this study were located within the genomic context mdtN-phnP previously reported in the species marcescens and now further extended to those of grimesii, inhibens, nematodiphila, plymuthica, and rubidaea. Three new possible contexts were also identified: one (puu genes-mnmA) shared by genomes of rubidaea and fonticola; and two (osmE-soxG and ampC-yebZ) detected in those of rubidaea. The context osmE–soxG might be closely linked to the cas gene set of subtype I-C (Table A2). Due to the low number of CRISPR-positive genomes of rubidaea and fonticola and genomes positive for the cas gene set I-C, further analyses are required to confirm this hypothesis.

A previous comprehensive study on the distribution of CRISPR–Cas systems in genomes of the Enterobacteriaceae family (now reorganized within the Enterobacterales order) showed the predominant presence of subtype I-E and the rare coexistence of subtypes I-E and I-F1 in the same genome (Medina-Aparicio et al., 2018). Our data show the prevalence of subtype I-F1 (39.5%), followed by subtypes I-E (about 5%), and I-C (about 5%). Detection of subtype I-C is the first report in Serratia. The prevalence of the subtype I-F1 in our subset of CRISPR-positive genomes is consistent with both the new reorganized Enterobacterales order (Adeolu et al., 2016) and data produced by Medina-Aparicio et al. (2018). Indeed, in the aforementioned study subtype I-F1 was found prevalent in genera Yersinia, Rahnella, and Serratia which are now part of the new Yersiniaceae family. On the other hand, the subtype I-E remains predominant within the Enterobacteriaceae family. Moreover, the finding of two distinct cas-gene sets (I-E/I-F1 or I-E*/I-F1) in only three Serratia genomes, confirms that the coexistence of these subtypes is not frequent. It is also important to note that the only Serratia strain harboring a type III system reported by Medina-Aparicio et al. (2018) is ATCC 39006. This strain was not included in our study due to recommendations stated by Sandner-Miranda et al. (2018) which highlighted the need to revise the assignment of the above-mentioned strain to the Serratia genus. In this respect, it is noteworthy that in any complete genomes and high-quality assemblies considered in our study, the type III system was not detected.

Six different cas-gene set architectures were identified of which those reported as I-E unique locus 1 (characterized by a 0.6 kb cas3/cas8e intergenic sequence), I-E* (characterized by the cas6e translocation between cas7 and cas11) and I-F1 unique locus 1 (characterized by 0.4 kb cas3/cas8f1 intergenic sequence) are, to the best of our knowledge, the first ever detected in Serratia. Similar or identical architectures of I-E unique locus 1, I-E*, and I-F1 unique locus 1 have been reported for other bacteria genera: a similar architecture to I-E unique locus 1 has been described in Escherichia coli (IGLB fragment) where the cas3/cas8e intergenic sequence was ~0.4 kb (Pul et al., 2010; Westra et al., 2010); an architecture identical to I-E* has already been detected in Klebsiella and Vibrio (I-E variant) strains (McDonald et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2017); a similar architecture to I-F1 unique locus 1 was reported in V. cholerae (I-FV1), where the cas3/cas8f1 intergenic sequence was ~0.1 kb (McDonald et al., 2019).

This study also supplies data on the presence/number of CRISPRs and their consensus DRs sequences in Serratia. Apart from canonical arrays (61.5% of the total disclosed arrays), orphans (29.4%) and aliens (10.2%) arrays were also detected (Table 1; Figure 1). Orphan arrays might represent remnants of previous complete CRISPR–Cas systems (Zhang & Ye, 2017). The presence of alien arrays found only in rubidaea complete genomes is, as far as we know, the first report in bacteria CRISPR-positive genomes. Its detection might be explained as traces of ancient complete CRISPR–Cas systems I-E/I-F1 or I-C/I-E/I-F1 coexistent within the same genome (Table 1). Alternatively, the aliens might result from single horizontal gene transfer events. Further analyses could unveil their genetic origin and the entity of their distribution among CRISPR-positive bacteria genomes. Detection of more alien arrays might unveil that the presence of multiple subtypes in a genome is more frequent than it has been reported so far. Furthermore, consensus DRs specifically associated with the cas gene set I-E* were also first described (Table 2).

Finally, the phylogenetic tree generated by multiple alignment of the Cas3 sequences showed a potential sub-lineage (I-E*) within the I-E branch and thus might represent and/or anticipate a distinct clonal expansion of an I-E sub-population (Figure 4).

Knowledge of CRISPR–Cas systems is constantly expanding due to studies on newly available genomic sequences or genomic sequences not yet explored. The CRISPR–Cas systems classification is thus continuously updating also in light of their possible applications. Indeed, the CRISPR–Cas technology has undoubtedly revolutionized systems of genome editing with a wide range of potential industrial and biomedical applications. Other, more recent genome-editing tools are based on methods that make use of the Cas9 protein (Arroyo-Olarte et al., 2021). However, expression of foreign proteins with DNA-binding and editing activity appears toxic for many bacteria. Harness of endogenous CRISPR systems is a recent and promising new line of approach for bacteria genome editing (Klompe et al., 2019; Strecker et al., 2019).

Our study has contributed to expanding knowledge of the variability and distribution of CRISPR systems in the Serratia genus. Data here presented might be exploitable for native CRISPR effectors of this genus that includes species (e.g., marcescens) relevant in environmental and clinical fields. Moreover, the detection of the same subtype of cas-gene sets in different Serratia species and other genera highlights the open question of the molecular mechanisms yet to be identified that have allowed intra- and inter-species spread.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Maria Scrascia: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Roberta Roberto: Formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal). Pietro Daddabbo: Formal analysis (equal). Yosra Ahmed: Data curation (equal). Francesco Porcelli: Conceptualization (equal). Marta Oliva: Investigation (equal). Carla Calia: Investigation (equal). Angelo Marzella: Investigation (equal). Carlo Pazzani: Methodology (equal); supervision (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Karen Laxton and Julian Laurence for their writing assistance. There are no funding agencies to report for this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None required.

APPENDIX

| Subtype of cas gene cluster | Species | Strain | Source | Place of isolation | Year of isolation | Assembly level | Accession/Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-C | rubidaea | NBRC 103169 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Contig | GCA_001598675.1 |

| I-C | rubidaea | CFSAN059619 | Throat | Pakistan | 1998 | Contig | NZ_JACYQC010000002 |

| I-E | marcescens | S8 | Rhynchophorus ferrugineus | Italy | 2013 | Contig | MK507744 |

| I-E | marcescens | AH0650_Sm1 | clinical | Australia | 2014 | Contig | GCA_001051865.1 |

| I-E | marcescens | EGD-HP20 | tannery waste | India | 2005 | Contig | GCA_000465615.2 |

| I-E unique locus 1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5683025 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2011 | Scaffold | GCA_001538785.1 |

| I-E unique locus 1 | marcescens | ML2637 | clinical | South Africa | 2016 | Scaffold | GCA_002118055.1 |

| I-E* | Serratia sp. | DD3c | Daphnia magna | Germany | 2008 | Contig | GCA_000496755.2 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682818 | blood | United Kingdom | 2002 | Scaffold | GCA_001539025.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682863 | blood | United Kingdom | 2004 | Scaffold | GCA_001539585.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC620 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418815.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC6001 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418835.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC6000 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418855.2 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC460 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418875.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC459 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418895.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MC458 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418915.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | AB42556419-isolate1 | clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_000418935.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682911 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | GCA_001537545.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5683032 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | GCA_001538705.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682819 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | GCA_001537145.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682934 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2007 | Scaffold | GCA_001538745.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682957 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2008 | Scaffold | GCA_001540825.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 2880STDY5682995 | clinical | United Kingdom | 2010 | Scaffold | GCA_001537925.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 684_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001065935.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | SM03 | clinical | India | 2012 | Scaffold | GCA_001909165.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | MGH136 | clinical | United States | 2015 | Scaffold | GCA_002153355.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | at10508 | clinical | Australia | 2017 | Scaffold | GCA_002250685.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 907_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Contig | GCA_001068085.1 |

| I-F1 | marcescens | 1145_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001060335.1 |

| I-F1a | fonticola | 5 l | Alces alces from permafrost | Russia | 2010 | Contig | GCA_001908045.1 |

| I-F1 | Serratia sp. | HMSC15F11 | clinical | N/A | N/A | Scaffold | GCA_001808215.1 |

| I-F1 | Serratia sp. | TEL | soil | South Africa | 2014 | Contig | GCA_001011075.1 |

| I-F1b | Serratia sp. | H1w | Phytotelma | Malaysia | N/A | Contig | GCA_000633355.1 |

| I-F1b | Serratia sp. | H1n | Phytotelma | Malaysia | N/A | Contig | GCA_000633315.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 410_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001063325.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 374_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001064725.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 454_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001064975.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 420_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001063375.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 398_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001064855.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 395_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001064835.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | 370_SMAR | clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | GCA_001064715.1 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | marcescens | S5 | Rhynchophorus ferrugineus | Italy | 2014 | Contig | MK507745 |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | grimesii | NBRC 13537 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Contig | GCA_001590905.1 |

| I-E; I-F1 | oryzae | J11-6 | rice | China | 2015 | Scaffold | GCA_001976145.1 |

| I-E*; I-F1 | Serratia sp. | Ag1d | Anopheles gambiae | France | 2014 | Contig | GCA_000743355.1 |

| I-E*; I-F1 | Serratia sp. | Ag2e | Anopheles gambiae | United States | 2014 | Contig | GCA_000743365.1 |

- Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

- a Stop codon detected in the gene cas8f.

- b Truncated sequence: flanking regions of the identified set of cas genes were not completely available.

- c Two arrays (26 DRs and 45 DRs) were detected.

- d Four arrays (5 DRs, 16 DRs, 20 DRs, and 27 DRs) were detected.

- e Four arrays (3 DRs, 5 DRs, 16 DRs, and 27 DRs) were detected.

| Subtype of cas gene cluster | CRISPRs | Species | Strain | Source | Place of isolation | Year of isolation | Assembly level | Accession/Assembly | Genomic contexts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConsensusDR type | #Arrays (#repeats) | |||||||||

| I-C | I-C | 1 (15) | rubidaea | FDAARGOS_926a | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | NZ_CP065640.1 | C |

| I-E | 1 (8) | A | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (6) | B | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (3) | D | ||||||||

| I-C | I-C | 1 (15) | rubidaea | NCTC12971a | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR590463.1 | C |

| I-E | 1 (8) | A | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (6) | B | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (3) | D | ||||||||

| I-C | N/A | N/A | rubidaea | CFSAN059619 | Throat | Pakistan | 1998 | Contig | NZ_JACYQC010000002 | C |

| I-C | N/A | N/A | rubidaea | NBRC 103169 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Contig | BCZJ01000003 | C |

| I-E | I-E | 2 (44, 31) | plymuthica | NCTC8900 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR134151.1 | A |

| I-E | I-E | 3 (11, 30, 31) | marcescens | S8 | Rhynchophorus ferrugineus | Italy | 2013 | Contig | MK507744 | A |

| I-E | N/A | N/A | marcescens | AH0650_Sm1 | Clinical | Australia | 2014 | Contig | LFJS01000001.1 | A |

| I-E | N/A | N/A | marcescens | EGD-HP20 | Tannery waste | India | 2005 | Contig | AVSR01000005.1 | A |

| I-E unique locus 1 | I-E | 4 (7, 9, 28, 45) | marcescens | E28 | Hospital Ensuite | Australia | 2012 | Complete genome | CP042512.1 | A |

| I-E unique locus 1 | I-E | 3 (8, 11, 23) | marcescens | SER00094 | Clinical | United States | 2017 | Complete genome | CP050447.1 | A |

| I-E unique locus 1 | I-E | 3 (12, 40, 70) | marcescens | MSB1_9C-sc-2280320 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR890657.1 | A |

| I-E unique locus 1 | I-E | 2 (36, 48) | plymuthica | NCTC8015 | Canal water | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR134478.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (7, 47) | marcescens | PWN146 | Bursaphelenchus xylophilus | Portugal | 2010 | Complete genome | LT575490.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (26, 28) | marcescens | 12TM | Pharyngeal secretions | Romania | 2014 | Complete genome | CM008894.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (9, 18) | marcescens | N4-5 | Soil | United States | 1995 | Complete genome | CP031316.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (4, 51) | marcescens | S5 | Rhynchophorus ferrugineus | Italy | 2014 | Contig | MK507745 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682818 | Blood | United Kingdom | 2002 | Scaffold | FCGU01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682863 | Blood | United Kingdom | 2004 | Scaffold | FCHP01000003.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | MC459 | Clinical | United States | N/A | Scaffold | ATOK01000005.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682911 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | FCFC01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5683032 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | FCFQ01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682819 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2006 | Scaffold | FCGD01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682934 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2007 | Scaffold | FCJR01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682957 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2008 | Scaffold | FCKI01000003.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 2880STDY5682995 | Clinical | United Kingdom | 2010 | Scaffold | FCLS01000002.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 454_SMAR | Clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | JVGM01000005.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 420_SMAR | Clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | JVHU01000010.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 395_SMAR | Clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | JVIU01000009.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 370_SMAR | Clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | JVJT01000036.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | SM03 | Clinical | India | 2012 | Scaffold | LZOB01000021.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | MGH136 | Clinical | United States | 2015 | Scaffold | NGUE01000001.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | at10508 | Clinical | Australia | 2017 | Scaffold | NPIX01000022.1 | A |

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | marcescens | 1145_SMAR | Clinical | United States | 2012–2013 | Scaffold | JWBL01000004.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (8, 18) | fonticola | 5 l | Alces alces from permafrost | Russia | 2010 | Contig | MQRH01000015.1 | B |

| I-F1 | I-F | 4 (12, 16, 23, 72) | fonticola | DSM 4576 | Water | N/A | 1979 | Complete genome | NZ_CP011254.1 | B |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (16, 25) | inhibens | PRI-2c | Maize rhizosphere soil | The Netherlands | 2004 | Complete genome | NZ_CP015613.1 | A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 6 (2, 8, 8, 15) | rubidaea | FDAARGOS_880 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | CP065717.1 | A |

| I-F | 1 (15) | B | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (4) | D | ||||||||

| I-F1 | N/A | N/A | Serratia sp. | TEL | Soil | South Africa | 2014 | Contig | LDEG01000006.1 | A |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | I-F | 3 (6, 11, 30) | marcescens | FZSF02 | Soil | China | 2014 | Complete genome | CP053286 | A |

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | I-F | 3 (4, 7, 8) | rubidaea | NCTC10036 | Finger | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR134493.1 | A |

| I-F | 1 (9) | B | ||||||||

| I-E | 1 (4) | D | ||||||||

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | I-F | 1 (11) | Serratia sp. | JUb9 | Compost | France | 2019 | Complete genome | CP060416.1 | B |

| I-F | 3 (3, 8, 8) | A | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (3) | D | ||||||||

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | I-F | 2 (16, 17) | rubidaea | FGI94 | Atta colombica | Panama | 2009 | Complete genome | NC_020064.1/CP003942.1 | A |

| I-E | 1 (10) | A | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (7) | B | ||||||||

| I-F1 unique locus 1 | N/A | N/A | grimesii | NBRC 13537 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Contig | BCTT01000008.1 | A |

| I-E | N/A | N/A | oryzae | J11-6 | Rice | China | 2015 | Scaffold | MOXD01000003.1 | F |

| I-F1 | Scaffold | MOXD01000008.1 | E | |||||||

| I-E* | I-E* | 2 (5, 20) | Serratia sp. | Ag1 | Anopheles gambiae | France | 2014 | Contigs | JQEI01000052.1; JQEI01000046.1 | N/A |

| I-F1 | I-F | 2 (16, 27) | Contig | JQEI01000002.1 | G | |||||

| N/A | I-C | 1 (10) | symbiotica | CWBI-2.3 | Aphis fabae | Belgium | 2009 | Complete genome | GCA_000821185.1 | H |

| N/A | I-E | 1 (27) | marcescens | KS10b | Marine | United States | 2006 | Complete genome | CP027798.1 | A |

| N/A | I-E | 1 (27) | marcescens | EL1b | Marine | United States | 2002 | Complete genome | CP027796.1 | A |

| N/A | I-E | 1(39) | marcescens | CAV1492 | Clinical | United States | 2011–2012 | Complete genome | NZ_CP011642.1 | A |

| N/A | I-E | 2 (4, 34) | marcescens | CAV1761 | Peri-rectal | Virginia | 2014 | Complete genome | CP029449.1 | A |

| N/A | I-E | 1 (3) | Serratia sp. | KUDC3025 | Rhizospheric soil | South Korea | 2017 | Complete genome | CP041764.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (22) | marcescens | SCQ1 | Blood from silkworm | China | 2009 | Complete genome | CP063354.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (4) | marcescens | AR_0130 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | CP028947.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (4) | marcescens | B3R3 | Zea mays | China | 2011 | Complete genome | NZ_CP013046.2 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (4) | nematodiphila | DH-S01 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | CP038662.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (7) | plymuthica | AS9c | Plant | Sweden | N/A | Complete genome | NC_015567.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (7) | plymuthica | AS12c | Plant | Sweden | 1998 | Complete genome | NC_015566.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (7) | plymuthica | AS13c | Plant | Sweden | N/A | Complete genome | NC_017573.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (3) | plymuthica | V4 | Milk processing plant | Portugal | 2006 | Complete genome | CP007439.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (2) | Serratia sp. | MYb239 | Compost | Germany | N/A | Complete genome | CP023268.1 | A |

| I-F | 1 (3) | B | ||||||||

| N/A | I-F | 1 (4) | Serratia sp. | SSNIH1 | N/A | United States | 2015 | Complete genome | CP026383.1 | A |

| N/A | I-F | 1 (5) | rubidaea | NCTC9419 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LR134155.1 | B |

| I-F | 1 (7) | D | ||||||||

| N/A | I-F | 1 (3) | rubidaea | NCTC10848 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Complete genome | LS483492.1 | A |

| I-E | 1 (4) | A | ||||||||

| I-F | 1 (7) | B | ||||||||

- Abbreviation: N/A: not applicable.

- a,b,c Possible multiple records of the same genome. Spacers’ sequences were identical.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (Appendix) and its Supporting Information files (Supporting Information: Table S1: List of Serratia genome assemblies; Supporting Information: Table S2: Spacer analyses; Supporting Information: Figure S1: Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene). Sequences used to generate the 16S tree are available via the reported accession numbers of all analyzed strains; cas gene sequences are available via the CRISPR–Cas++ database at https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/MainDb/StrainList.