The ongoing impact of COVID-19 on the clinical education of Australian medical radiation science students

Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant and ongoing impact on health care, particularly for medical radiation science (MRS) professionals. There exist many studies that describe the negative effects of clinical placement restrictions and access to universities on the well-being of all health professional students during the pandemic. There also exists evidence of changes to MRS student teaching and impacts to students and academic clinical educators; however, there exists a paucity of research that investigates how changes have affected the performance of students within the clinical environment and entering the workforce. This study surveyed workplace MRS clinical educators within Australia to gather their perspectives regarding the impact of COVID-19 on student clinical education.

Methods

A descriptive study comprising an online structured survey of 44 questions was provided to Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy Clinical Educators across Australia.

Results

A total of 55 survey responses were received. Of note, respondents described heavy reductions to student intake capacity, losses of clinical placement time, a noted theory–practice gap and possibility of sites ‘failing to fail’ students. Negative impacts to all domains of MRPBA professional capabilities, as well as a perceived unpreparedness to meet the MRPBA capabilities were described. There was general agreement that graduating students will require supportive periods upon entry into the profession.

Conclusion

This study highlights the considerable impact of changes to the education and training of MRS students in response to COVID-19. The results pose a real concern for a generation of MRS students affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant and ongoing impact on health care, including radiographers and radiation therapists.1-5 These frontline healthcare professionals played a vital role in hospitals and community centres throughout the fight against COVID-19 but perhaps did not get much public attention.1, 5, 6 Literature has detailed the use of radiation therapy as treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia,7-11 the use of CT as a diagnostic test for COVID-19 pneumonia12-15 and changes to the provision of medical imaging, particularly the use of mobile chest radiography.16, 17 Beyond this, the physical and emotional impacts of healthcare provision throughout the pandemic and the difficulties faced by medical radiation science (MRS) professionals have been well documented.1, 4, 5

From a student perspective, many studies describe the negative effects of clinical placement restrictions and access to universities on the well-being of all health professional students during the pandemic.6, 18-23 Some describe strategies to maintain quality of student placement and clinical training.24, 25 Many report the changes to education delivery within universities as well as within the clinical departments actively managing the delivery of care during the crisis.18-21, 26-32 Within academic institutions, a large focus of literature was on shifting the delivery of content to online, as well as the implementation of simulation training, either to support clinical placements or to replace them.18, 20, 21, 27-30

Many reports focused on how changes to MRS student teaching were felt by the students and university educators. Yet, there exists a paucity of research exploring how these changes have affected the performance of students within the clinical environment and entering the workforce. This challenge of students, now in the workplace following pandemic impacted years of study, is currently being felt. McConnell et al, in their letter to the editor, pose questions around the effect of the changes seen during the pandemic, in particular the loss of clinical exposure and what this may mean for the profession in terms of workforce shortages.33 Furthermore, the authors hint at the effect of continued loss of clinical opportunity and the requirement for longer periods of supervised practice or clinical placement time in order for students to recoup lost clinical experience.33 McConnell et al. also questions whether the loss of clinical experience has any impact on student preparedness.20, 33

Teo et al. postulate that there are difficulties for students to put theories into practice and a theory–practice gap as a result of the move to online delivery of content.31 The authors describe challenges to learning due to solely being online and some of the effects that this has had on student development. In a separate study, Tay et al. support the concept of a theory–practice gap and question the ramifications of this as students move from students to novice professionals.24 They raise concerns that pressures and the emotional stress of managing student placements through the difficulties of the pandemic may have also lead to clinical educators ‘failing to fail’ underperforming students.24 Commentary on curated orientation programs for student radiographers, provided by Tay et al., identifies the need for more supportive workforce orientation programs in the post-COVID era.34

MRS clinical educators, those educators employed and engaged by the healthcare providers to manage student placements within the clinical sites, are arguably best placed to judge the clinical performance of MRS students and to provide perspective on the concerns raised about the effects that COVID related changes have made to student placements and preparedness for the workforce. This study aimed to survey MRS clinical educators within Australia to gather their perspectives regarding the impact of COVID-19 on student clinical education, specifically the preparation for clinical placement, changes in performance and preparedness to enter the workforce.

Methods

A descriptive study of MRS clinical educator perspectives was conducted. An online structured survey comprising 44 questions was provided to Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy Clinical Educators across Australia via existing email lists maintained by clinical educator networks. The survey was accompanied by a participant information form and completion of the survey implied consent. Nuclear Medicine Clinical Educators were not included in the survey, due largely to a lack of access to nuclear medicine clinical educator networks at the time of preparation of the study.

Recruitment relied on active engagement of clinical educators through word of mouth and snowball sampling to identify relevant contacts. Clinical educators were only included where they were the clinical educator for a clinical site that managed student placement. University educators were not included in the study as the study aimed to assess the clinical abilities of students in the clinical environment. The survey was pilot tested by a team of four clinical MRS professionals to assess ease of use and approximate duration of completion (around 30 min).

The questionnaire sought participant demographic data, alongside perspectives on four areas relating to the effects of the pandemic, including student placement, student preparedness for placement, student performance and student well-being. Questions were a mix of ranked alternatives and ratings using a 5-point Likert scale. To provide a tool for describing student performance, questions were framed against the Medical Radiations Practice Board of Australia (MRPBA) professional capabilities.35

The questionnaire was released for completion for a one-month period from 17 June to 17 July 2022, with a reminder email sent via the email lists approximately a week prior to the closure of the survey. Survey responses were collected through the REDCap™ data management system.

The project received ethics approval through the Royal Children's Hospital Ethics Panel (HREC/85714/RCHM-2022).

Data analysis

Quantitative results were analysed by descriptive statistics, including the number and percentages of respondents answering in different categories (e.g. Likert scale responses or other response categories). Given the limited number of MRS clinical educators across the country, the extensive nature of the questionnaire, and that not all participants answered all questions, it was decided that for all questions the denominator would be taken as the number responding to the question and not the total number of participants.

Results

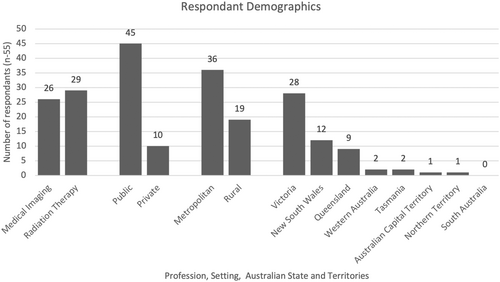

A total of 55 survey responses were received from clinical educators, 45 (82%) identifying roles within public hospital sites and 10 (18%) representing private services. Of the educators, 36 (65%) classified their service as metropolitan and 19 (35%) were from regional or rural clinical sites. The disciplines were relatively evenly represented, with 26 medical imaging clinical educators and 29 radiation therapy educators undertaking the survey.

Responses were recorded from all states except for South Australia, where no responses were received. Most responses from Victoria followed by New South Wales and then Queensland (Fig. 1), which is in keeping with access to clinical educators. Due to small study numbers, we did not analyse for differences in responses between states. Most participants indicated that they were the sole clinical educator (27/55, 49%) and described themselves as the lead clinical educator (45/55, 82%). Most lead clinical educators (28/45, 62%) had this role for the entire organisation, and the rest held the role for a particular site within their organisation (17/45, 38%).

Clinical placement

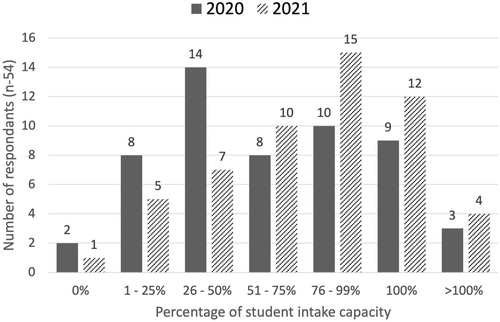

Prior to the pandemic, half of the respondents (30/54) indicated 16 or more student placements were offered per year. Almost half of the participants reported student intake capacity dropped to less than half of previous intake. A minority of respondents reported that student placements were at the same or increased levels during the pandemic (12/54, 20% for 2020 placements and 16/24, 30% for 2021 placements; Fig. 2).

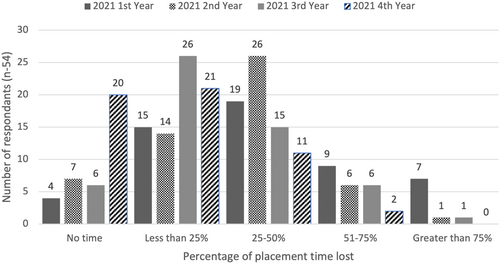

Around half (26/55, 48%) of the respondents estimated around 25–50% of lost placement time during the pandemic, and more than a third (21/55, 38%) indicated 25% of placement time or less was lost to students (Fig. 3). Most respondents (48/55, 89%) indicated a negative impact on student clinical education from the pandemic.

Prioritising the areas of clinical placement most impacted, clinical educators identified group social opportunities, clinical staff availability and clinical staff burnout. When ranking the top areas where they perceived students' clinical education required additional support educators identified clinical time, patient interaction and exposure to a variety of clinical experiences.

Before the pandemic restrictions, all clinical educators (25/25, 100%) believed that there were sufficient opportunities for students to meet placement requirements and gain hands-on experience. However, during the restrictions, most (21/25, 84%) felt that these opportunities were inadequate. Following the lifting of restrictions, just over two thirds of respondents (18/25, 72%) felt that the level of opportunity was sufficient, indicating that opportunities had not fully returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Student performance

Most respondents (29/34, 85%) agreed or strongly agreed that there was a theory to practice gap, and the majority (26/37, 70%) indicated that virtual or simulated training did not adequately prepare students for placement. Many respondents, 15 of 34 (44%), also somewhat agreed that clinical sites were ‘failing to fail’ students whose learning may have been impaired by the pandemic.

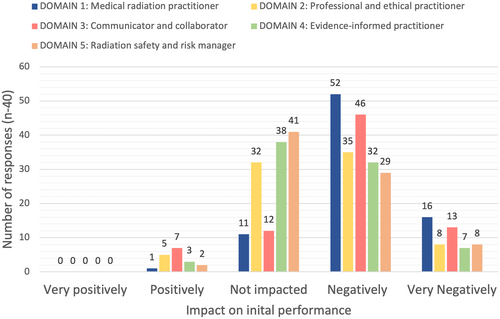

Across all domains of the MRPBA professional capabilities respondents perceived negative impacts on the student's performance as a result of placement limitations during the pandemic. This was most apparent in responses to impacts on Domain 1 (medical radiation practitioner) and Domain 3 (communicator and collaborator) where most responses (34/40, 85% and 29/40, 73%, respectively) describe negative impacts to student performance (Fig. 4).

Clinical educators were asked about their perception of the preparedness of students to meet the professional capabilities prior to the pandemic as well as during 2020 and 2021. Of responses around preparedness prior to the pandemic, most clinical educators (35/39, 90%) felt that students were prepared to meet the MRPBA professional capabilities. Opinions changed considerably during the years of the pandemic, with most responses (23/39, 59%) believing that students were unprepared or very unprepared to meet the same in both 2020 and 2021 (Table 1).

| Very prepared (n, %) | Prepared (n, %) | Neutral (n, %) | Unprepared (n, %) | Very unprepared (n, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to the pandemic | 6, (15.4%) | 29, (74.4%) | 4, (10.3%) | 0, (0.0%) | 0, (0.0%) |

| During the pandemic in 2020 | 0, (0.0%) | 8, (20.5%) | 8, (20.5%) | 20, (51.3%) | 3, (7.7%) |

| During the pandemic in 2021 | 0, (0.0%) | 9, (23.1%) | 7, (17.9%) | 20, (51.3%) | 3, (7.7%) |

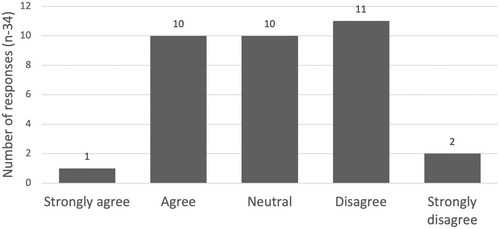

There was a split amongst the opinions of educators to the statement: ‘students are well prepared to enter the workforce despite COVID’ (Fig. 5). Furthermore, more than three quarters of clinical educators believed that graduating students require supportive periods upon entry into the profession (26/34, 74%). When asked to nominate the duration of this support, most educators recommended a provision of support for a period of 6–12 months.

Discussion

This study highlights the considerable amount of clinical placement time that was lost to MRS students in Australia during the two most impacted years of the COVID pandemic, and perceived negative impacts on the students' capabilities and preparedness to enter the workforce. Clinical educators described the areas where they perceived students required additional support for their education, including patient interaction, and exposure to a variety of clinical experiences, all of which stem from both the loss of placement time and opportunities within them. Even with the easing of restrictions, close to one in three clinical educators still felt that opportunities within placements were insufficient to meet requirements of the placement in contrast with pre-pandemic conditions.

These findings have implications for the current MRS workforce and ongoing student development, in particular the perception that graduates may be unable to meet the professional capabilities prescribed by the MRPBA due to the forced reduction in clinical placement time. Those nearing the end of their degree programs without an opportunity to make up lost clinical placement time may struggle to meet elements of the capabilities. While there was a shift to virtual training during the pandemic, most clinical educators perceived it did not adequately replace in-person experience. This is in contrast to literature highlighting the utility of virtual training technologies as a useful tool.18, 21, 27, 29, 30 This is not to say that such approaches lack utility and were not necessary during the pandemic, but that it is important to question outcomes from such approaches and recognise the learning they cannot replace. It is important to recognise the consequences that may still be felt in the workforce, given that online learning environments can be impersonal and course material during this period may have commonly been provided as recorded content, with a more didactic or theoretical approach. This may present barriers for students engaging with lecturers and other students and, by extension, the ability to question and problem-solve with experts and peers.

Close to half of clinical educators agreed that clinical sites were failing to fail students during the pandemic, which supports assertions made by Tay et al.24 This links with the pressures placed on clinical educators during this time and the relaxation of clinical standards that had to be adopted in order to meet workforce demands and those that restrictions imposed. These, combined with other perceived impacts described in this study, such as a theory to practice gap and reduced professional capacities, paint a worrying picture for this generation of the profession.

The findings suggest that additional support, either enhanced or a longer period of supportive supervision on workforce entry, is likely to be needed. Tay et al.34 describe curated orientation programs or tailored upskilling programs and further describe closer mentoring with more deliberate mechanisms for evaluating skills, including broader aspects of professionalism. These concepts would seem to be in keeping with the suggestions of clinical educators participating in this study. While many pandemic-forced changes have long since passed, a small generation of newly graduated MRS professionals may be impacted for some time. A focus for this generation of professionals towards continuing professional development would seem vital as would careful reflection and/or evaluation of knowledge and skills.

Development of not only technical skills and knowledge but also the ability to communicate, collaborate and engage in the clinical environment should be a focus for continued professional development. The generation of students affected by the changes imposed because of the pandemic often learned in an isolated environment, and it would seem prudent to fully engage these students in collaborative team-based environments as a core part of their continuing professional development. Increased opportunity for face-to-face seminars and workshops, that focus on ‘back to basics’ themes could potentially be beneficial, not only to provide education but also the opportunity to converse and network with other professionals. Auditing, skills evaluation and mentorships within departments would allow for assessment of deficiencies and the establishment of tailored education programs that aim to specifically remedy identified inadequacies.

Solutions are possible. Yet, it must be remembered that any solution has to be delivered by a workforce which has already described their own burn out during the pandemic, while delivering on existing student commitments.36, 37 The cost of not investing in new or enhanced approaches may, however, lead to longer term implications for the workforce and profession.

Limitations

There are several limitations with this study, including the limited number of responses and the number of partially completed surveys received. There is, however, a limited number of clinical educators across Australia, which means the sample is likely representative. Furthermore, COVID-19 affected the clinical environment and student teaching and training in a broad number of ways, many of which had crossover and/or impact on others. This makes specific conclusions about causal effects difficult.

Conclusion

This study highlights the considerable impact of changes made to the education and training of MRS students in response to COVID-19. The responses of clinical educators, overseeing students on clinical placement, describe a notable reduction on the technical skills, knowledge and preparedness for clinical placement and, more concerning, entry into the profession. The results highlight a perceived deficit in the theory to practice gap and large impacts on student ability to meet professional capabilities. Clinical educators describe a need for extended or enhanced periods upon graduation for this generation of students. Regular evaluation of skills and knowledge, along with considered structured professional development program, that includes in-person learning and targets learning gaps should be undertaken in the formative years following graduation.

Funding Information

This study was not funded by any external sources, and all costs were met by the researchers.

Ethics Statement

The project received ethics approval through the Royal Children's Hospital Ethics Panel (HREC/85714/RCHM-2022).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.