Efficacy of staging laparoscopy for resectable pancreatic cancer on imaging and the therapeutic effect of systemic chemotherapy for positive peritoneal cytology

Abstract

Background

The frequency and prognosis of positive peritoneal washing cytology (CY1) in resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (R-PDAC) remains unclear. The objective of this study was to identify the clinical implications of CY1 in R-PDAC and staging laparoscopy (SL).

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 115 consecutive patients with R-PDAC who underwent SL between 2018 and 2022. Patients with negative cytology (CY0) received radical surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, while CY1 patients received systemic chemotherapy and were continuously evaluated for cytology.

Results

Of the 115 patients, 84 had no distant metastatic factors, 22 had only CY1, and nine had distant metastasis. Multivariate logistic regression revealed that larger tumor size was an independent predictor of the presence of any distant metastatic factor (OR: 6.30, p = .002). Patients with CY1 showed a significantly better prognosis than patients with distant metastasis (MST: 24.6 vs. 18.9 months, p = .040). A total of 11 CY1 patients were successfully converted to CY-negative, and seven underwent conversion surgery. There was no significant difference in overall survival between patients with CY0 and those converted to CY-negative.

Conclusion

SL is effective even for R-PDAC. The prognosis of CY1 patients converted to CY-negative is expected to be similar to that of CY0 patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies, with an estimated 5-year relative survival rate of 12%.1 In Japan, PDAC is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths.2 Although surgical resection is the only potentially curative option, postoperative recurrence is common, and the 5-year recurrence-free survival rate is reported to be 8%–30%2-4 even with multidisciplinary treatment. Above all, pancreatic cancer with peritoneal dissemination has a poor prognosis, with a median survival period of approximately 7 months.5 Peritoneal dissemination is one of the most frequent causes of postoperative treatment failures, accounting for 33% of initial sites.6

Pancreatic cancer always involves the concern of systemic micrometastasis.7-10 The assumption that free cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity are an early stage of peritoneal dissemination is now widely accepted. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual (AJCC),11 the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)12 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),13 positive peritoneal washing cytology (CY1) is defined as distant metastasis. Staging laparoscopy (SL) with peritoneal washing cytology is not widely performed, and its significance in detecting microscopically disseminated cancer cells is unclear. Therefore, according to the recent Japanese protocol (General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer seventh edition14), CY1 is not defined as distant metastasis. Satoi et al5 reported that SL revealed distant metastases such as liver metastases or peritoneal dissemination in 34% and 24% of patients diagnosed with unresectable locally advanced (UR-LA) PDAC on imaging. Moreover, a recent nationwide study reported that patients with CY1 have a poorer prognosis than patients with negative cytology (CY0) following resection of PDAC.15-17 On the other hand, the significance of SL, the frequency of CY1 patients with resectable (R) PDAC, and the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy and its prognosis are not well defined.

In the current study, we appraise the results of SL in patients with R-PDAC before the initial treatment and the outcomes and prognosis of treatment with systemic chemotherapy according to CY status.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and patient selection

In this retrospective study, 115 consecutive patients with a preoperative diagnosis of R-PDAC on imaging who underwent SL before the initial treatment between December 2018 and August 2022 at the University of Toyama (Toyama, Japan) were analyzed.

All patients eligible for inclusion in this cohort were required to have preoperative imaging findings of R according to the NCCN guidelines.13 Resectability was assessed with multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT), ethoxybenzyl magnetic resonance imaging (EOB-MRI), positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET-CT),18 and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Patients who had already received chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded from this analysis.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee, University of Toyama (approval no. R2019138) and complied with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.19 All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for treatment was obtained from each patient prior to the start of treatment, and consent for the use of data for research was obtained on an opt-out basis.

2.2 Data collection

We collected all data regarding the patients’ clinical courses from medical records, operative reports, and pathological reports maintained by our institute.

The clinicopathological factors analyzed in this study were as follows: pretreatment factors (i.e., age, sex, body mass index, location of the tumor [head or body/tail of the pancreas], tumor size, duration from endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration [EUS-FNA] to SL, whether the tumor contacts the superior mesenteric vein or portal vein, and blood test results, including serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels); perioperative factors of SL (e.g., presence of metastasis, incidence of postoperative complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification20); treatment regimen (i.e., first-line regimen, second-line regimen); and pathological factors (e.g., results of washing cytology).

2.3 Peritoneal washing cytology

We performed SL before the start of treatment to evaluate the presence of distant metastases, such as liver metastases (H) and macroscopic peritoneal dissemination (P) and collected the peritoneal washing fluid.14 We inserted a soft catheter into the pouch of Douglas and introduced 100 mL of saline, and after slight agitation, we collected as much peritoneal washing fluid as possible. These samples were immediately sent to the department of pathology and centrifuged. The smear was made using Papanicolaou and Diff-Quick staining. Two experienced pathologists identified malignant cells in smears. In the pathological diagnosis of peritoneal washing cytology, Class V was regarded as CY1. Pathological results were intraoperatively reported to the surgeons within an hour after submission.

For patients with CY1, we principally implanted an abdominal port into the subcutaneous area of the right lower quadrant, and the catheter of the abdominal port was placed in the pouch of Douglas to allow peritoneal washing cytology during subsequent chemotherapy.

2.4 Treatment strategy

Patients with CY0 and no distant metastasis were treated with two cycles of gemcitabine and S-1 as preoperative chemotherapy. After imaging and biological markers were evaluated and it had been confirmed that there was no tumor progression, the patient underwent radical surgery.

Patients with CY1 were treated with systemic chemotherapy such as nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (GnP) or modified FOLFIRINOX as patients with distant metastasis, and imaging and tumor markers such as CA19-9 were continuously evaluated. In addition, peritoneal washing cytology was performed monthly using an abdominal port. We injected 100 mL saline through the abdominal port and collected as much as possible from the abdominal cavity. These fluids were sent to the department of pathology and evaluated using Papanicolaou, Periodic Acid-Schiff, and Giemsa-stained slides. Pathological results were generally reported 1–2 weeks later. If the cytology from the abdominal port was reported as negative, the tumor status and the imaging and tumor markers of the patients were re-examined. After confirming that the tumor had not progressed, second-look SL was performed occasionally, and then “conversion surgery (CS)” was performed.21

We defined “CY negative conversion” as two or more consecutive negative washing peritoneal cytology results from the abdominal port or negative washing peritoneal cytology results at the second-look SL.

2.5 Follow-up

Adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 was administered for at least 6 months for patients who underwent radical surgery. Postoperative follow-up was conducted at least every 2–3 months. Patients with CS continued systemic chemotherapy as an adjuvant for at least 6 months. Adjuvant chemotherapy was mainly performed using GnP or S-1. For patients who did not achieve CS, treatment continued until progression of the local status or a new metastatic lesion was evident.

2.6 Statistical analysis

A biostatistician (K.M.) was responsible for the statistical analysis. Binomial and continuous variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test and nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. All optimal cutoff values for the logistic regression were determined using the Youden index. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression to generate odds ratios, including 95% CIs, for clinical factors that would predict distant metastatic factors or H0P0CY1. Variables included in the multivariate models for H0P0CY1 had a p-value of .1 or less in the univariate analysis.

Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for between-group comparisons. The overall survival was measured from the date of SL or first chemotherapy until the date of patient death or most recent follow-up. No statistical hypothesis was set, and multiplicity was not accounted for because all analyses were performed in an exploratory manner. A p-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro Version 16 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline patient characteristics

Table S1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 115 patients with R-PDAC. Tumors were more common in the pancreatic head (53%) than in the pancreatic body and tail (47%). In more than half of the patients, the tumor made no contact with the portal venous system (64%). The median duration from EUS-FNA to SL was 18 days. There were only two postoperative complications associated with SL: anuria (grade I) and pain associated with the abdominal port (grade IIIb). No mortality after SL was observed in this study.

3.2 Study population

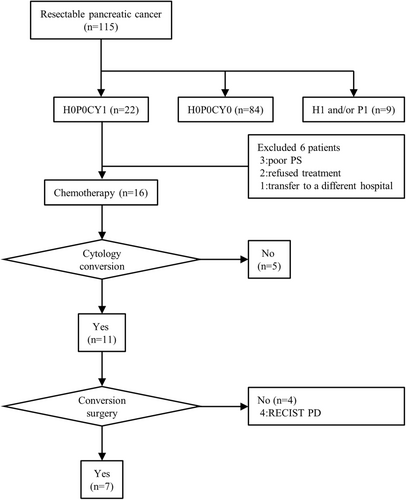

During the study period, a total of 115 patients with R-PDAC underwent SL (Figure 1). Of them, 22 (19%) patients had no distant metastatic factors, such as liver metastasis or peritoneal dissemination, but cytology of peritoneal washing fluid was positive (H0P0CY1). A total of 84 (73%) patients had no distant metastatic factors (H0P0CY0). There was one patient with class III peritoneal washing cytology but no patient with class IV at the time of SL. The class III patient was treated as CY0. Nine patients (8%) had liver metastasis or peritoneal dissemination (H1 and/or P1).

Of the 22 patients whose distant metastatic factor was only CY1, 16 were treated with systemic chemotherapy. A total of 15 were treated with GnP, and 1 was treated with modified FOLFIRINOX. A total of 11 of 16 patients who received chemotherapy showed a negative status following peritoneal washing cytology sampled from the abdominal port or at the time of second-look SL. CS was performed in seven patients (32%). Despite negative conversion of peritoneal washing cytology, CS was not performed due to disease progression in four patients. Among these four patients, liver metastases appeared in two, lung metastases in one, and local progression in one, and tumor markers in all of them gradually increased. The best supportive care was provided after an average of 18.5 months of chemotherapy.

Among 84 H0P0CY0 patients, 68 patients (81%) underwent radical surgery after preoperative chemotherapy, while three patients underwent upfront surgery due to aging. A total of 13 patients did not undergo pancreatectomy due to newly discovered metastatic lesions; 10 patients showed disease progression during preoperative chemotherapy and three were high-risk surgical patients (data not shown). The class III patient who was treated as CY0 underwent preoperative gemcitabine and S-1 therapy. The patient underwent radical surgery, at which time the peritoneal washing cytology was Class I. After surgery, the patient was treated with S-1 as adjuvant chemotherapy and survived for 28.3 months after the first chemotherapy. No peritoneal recurrence occurred.

3.3 Predictive factors in the SL results

In Table S2, the clinical characteristics were compared between 84 patients who had no distant metastatic factors (H0P0CY0) and 31 patients with distant metastatic factors (non-H0P0CY0). The non-H0P0CY0 group had a significantly larger tumor size (p = .038) and higher CA19-9 (p = .039) and DUPAN-2 (p = .020) levels than the H0P0CY0 group. Patients with tumors in the pancreatic body and tail tended to have more distant metastatic factors. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the other tumor markers, contact with the portal venous system, or time from EUS-FNA to SL.

The factors predicting distant metastasis in SL are shown in Table 1. Univariate logistic regression showed that lower body mass index, larger tumor size, and higher levels of tumor markers, including CA19-9, CEA, DUPAN-2, and CA125 were significantly associated with the presence of distant metastatic factors (H, P, CY) during SL. Multivariate analysis showed that larger tumor size and lower body mass index were independent predictors of distant metastatic factors (odds ratio, 6.30; 95% CI: 2.03–19.57; p = .002, and odds ratio, 4.23; 95% CI: 1.26–14.25; p = .020). The cutoff value for tumor size was 31 mm (Youden index 0.297).

| n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Body mass index | |||||||

| <21.9 kg/m2 | 50 | 6.07 | 2.41–15.32 | <.001 | 6.30 | 2.03–19.57 | .002 |

| ≥21.9 kg/m2 | 65 | ||||||

| Location of the tumor | |||||||

| Pbt | 54 | 2.22 | 0.95–5.15 | .064 | |||

| Ph | 61 | ||||||

| Tumor size | |||||||

| ≥31 mm | 27 | 4.50 | 1.79–11.31 | .001 | 4.23 | 1.26–14.25 | .020 |

| <31 mm | 88 | ||||||

| CA19-9 | |||||||

| ≥143 U/mL | 45 | 2.92 | 1.25–6.82 | .013 | 2.02 | 0.51–7.95 | .315 |

| <143 U/mL | 70 | ||||||

| CEAa | |||||||

| ≥5.2 ng/mL | 28 | 2.65 | 1.07–6.54 | .035 | 1.31 | 0.36–4.75 | .683 |

| <5.2 ng/mL | 86 | ||||||

| DUPAN-2a | |||||||

| ≥200 U/mL | 51 | 3.05 | 1.29–7.21 | .011 | 1.82 | 0.51–6.46 | .355 |

| <200 U/mL | 63 | ||||||

| CA125a | |||||||

| ≥14 U/mL | 39 | 2.64 | 1.07–6.51 | .035 | 1.18 | 0.37–3.83 | .778 |

| <14 U/mL | 53 | ||||||

| Contact with SMV or PV | |||||||

| Yes | 41 | 1.20 | 0.51–2.81 | .678 | |||

| No | 74 | ||||||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Pbt, pancreatic body and tail; Ph, pancreatic head; PV, portal vein; SMV, superior mesenteric vein.

- a Include missing values.

When examining predictive factors for H0P0CY1 only (Table 2), multivariate analysis also showed that larger tumor size and lower body mass index were independent predictors (OR: 8.38; 95% CI: 2.28–30.78; p = .001, and OR: 5.71; 95% CI: 1.45–22.44; p = .013).

| n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Body mass index | |||||||

| <21.8 kg/m2 | 42 | 8.02 | 2.67–24.14 | <.001 | 8.38 | 2.28–30.78 | .001 |

| ≥21.8 kg/m2 | 64 | ||||||

| Location of the tumor | |||||||

| Pbt | 48 | 2.02 | 0.78–5.25 | .148 | |||

| Ph | 58 | ||||||

| Tumor size | |||||||

| ≥32 mm | 22 | 5.00 | 1.77–14.12 | .002 | 5.71 | 1.45–22.44 | .013 |

| <32 mm | 84 | ||||||

| CA19-9 | |||||||

| ≥143 U/mL | 40 | 2.11 | 0.81–5.47 | .124 | |||

| <143 U/mL | 66 | ||||||

| CEAa | |||||||

| ≥5.2 ng/mL | 23 | 1.95 | 0.68–5.58 | .211 | |||

| <5.2 ng/mL | 82 | ||||||

| DUPAN-2a | |||||||

| ≥200 U/mL | 44 | 2.42 | 0.93–6.32 | .071 | 1.90 | 0.53–6.74 | .323 |

| <200 U/mL | 61 | ||||||

| CA125a | |||||||

| ≥14 U/mL | 34 | 2.48 | 0.91–6.81 | .077 | 1.42 | 0.41–4.90 | .575 |

| <14 U/mL | 50 | ||||||

| Contact with SMV or PV | |||||||

| Yes | 38 | 1.31 | 0.50–3.43 | .579 | |||

| No | 68 | ||||||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Pbt, pancreatic body and tail; Ph, pancreatic head; PV, portal vein; SMV, superior mesenteric vein.

- a Include missing value.

3.4 Treatment course for H0P0CY1 patients

In Table 3, we compared the clinical characteristics of H0P0CY1 patients at SL who received chemotherapy. A total of 11 patients underwent peritoneal washing cytology from the abdominal port and finally converted to a negative result, but five patients were not converted to a negative status. Patients whose cytology was converted to negative were significantly more likely to be male (p = .005) and had lower CA19-9 levels before the first chemotherapy (p = .005). In contrast, there were no significant differences in tumor size or other tumor markers. The cutoff value for CY negative conversion for CA19-9 was 218 U/mL (Youden index 0.818). Of the five patients who did not achieve negative conversion of cytology, three died, one was difficult to follow up, and one was undergoing chemotherapy but had distant metastasis. The mean survival from the start of chemotherapy was 14.5 months. In addition, of the six patients who did not receive chemotherapy, four died, and two were difficult to follow up. The mean survival from the date of SL was 11.0 months.

| Cytology conversion | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n = 11 | No n = 5 | ||

| Age (years)a | 69 (54–80) | 73 (70–81) | .078 |

| Sex (male/female) | 9/2 | 0/5 | .005 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 20.3 (18.6–24.9) | 19.9 (15–21.8) | .308 |

| Location of the tumor (Ph/Pbt) | 6/5 | 1/4 | .308 |

| Tumor size (mm)a | 21 (14–37) | 32 (26–37) | .089 |

| CA19-9 (U/mL)a | 41 (1–333) | 729 (143–1079) | .005 |

| CEA (ng/mL)a | 1.3 (1.1–5.6) | 3.4 (2.9–5.2) | .099 |

| DUPAN-2 (U/mL)a | 50 (25–1600) | 260 (240–710) | .156 |

| CA125 (U/mL)a | 13 (5–66) | 16 (5–65) | .610 |

| Contact with SMV or PV (yes/no) | 6/5 | 1/4 | .308 |

| Duration from EUS-FNA (days)a | 15 (3–28) | 7 (1–36) | .744 |

- Abbreviations: EUS-FNA, endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration; Pbt, pancreatic body and tail; Ph: pancreatic head; PV, portal vein; SMV, superior mesenteric vein.

- a Median (range).

Table 4 shows the clinical course of 11 patients who successfully converted to CY-negative. In most patients, the first-line regimen was GnP, and the median number of courses was four. The median number of courses required for CY-negative conversion was two courses, and the median period from the start date of chemotherapy to CY-negative conversion was 55 days. Seven of 11 patients who received first-line chemotherapy and showed stable disease (SD) or a partial response (PR) according to the RECIST criteria22 underwent CS. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy included S-1 in five patients and GnP in two patients. Four patients who did not undergo surgery due to progressive disease (PD) had distant metastases: liver metastases in two, lung metastases in one, and peritoneal dissemination in only one.

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | Location of tumor | CA19-9 before SL (U/mL) | CA19-9 after first line regimen (U/mL) | Tumor size before SL (mm) | Tumor size after first line regimen (mm) | First-line regimen | Number of first-line cycles | Number of courses required for conversion to negative cytology | Efficacy of first line chemotherapy according to the RECIST15 guidelines | Surgical technique of CS | Adjuvant chemotherapy | Metastasis after CS | Newly distant metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | Male | Head | 90 | 6 | 14 | 14 | GnP | 12 | 3 | SD | SSPPD + PVr | S-1 | Liver | – |

| 2 | 72 | Male | Tail | 195 | 82 | 18 | 17 | GnP | 3 | 3 | SD | LDP | GnP | Peritoneal dissemination | – |

| 3 | 77 | Male | Tail | 13 | 12 | 32 | 20 | GnP | 5 | 2 | PR | RDP | S-1 | Liver, peritoneal dissemination | – |

| 4 | 54 | Female | Body | 23 | 23 | 21 | 15 | GnP | 3 | 3 | PR | RDP | S-1 | – | – |

| 5 | 71 | Male | Tail | 41 | 7 | 20 | 16 | GnP | 3 | 1 | SD | RDP | GnP | – | – |

| 6 | 69 | Male | Head | 1 | 4 | 37 | 25 | GnP | 4 | 1 | PR | SSPPD + PVr | S-1 | – | – |

| 7 | 80 | Male | Head | 32 | 9 | 18 | 16 | GnP | 5 | 2 | SD | SSPPD + PVr | S-1 | – | – |

| 8 | 69 | Male | Body | 333 | 308 | 15 | 22 | GnP | 2 | 1 | PD | – | – | – | Lung |

| 9 | 68 | Male | Head | 86 | 211 | 23 | 39 | GnP | 3 | 2 | PD | – | – | – | Peritoneal dissemination |

| 10 | 67 | Male | Head | 45 | 38 | 27 | 37 | mFFX | 7 | 5 | PD | – | – | – | Liver |

- Abbreviations: CS, conversion surgery; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors: SL, staging laparoscopy.

3.5 Survival analysis

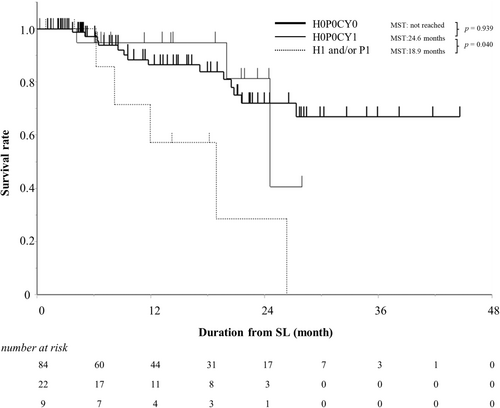

The median observational period from the date of SL to the date of death or censoring was 13 months. Of the 115 patients with resectable pancreatic cancer who received preoperative chemotherapy, 22 died due to cancer progression, one died due to bowel obstruction, and one died due to lung cancer. The MST was not obtained, and the 1-year survival rate was 85%. The prognosis of the H0P0CY0 group was not significantly different from that of the H0P0CY1 group (p = .939), and the prognosis of the H0P0CY1 group was significantly better than that of the H1 and/or P1 group (p = .040) (Figure 2).

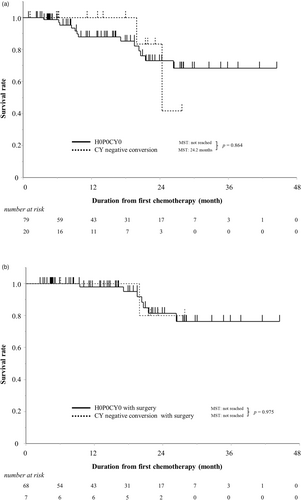

Next, the prognosis of the patients with H0P0CY0 and H0P0CY1 who were converted to CY-negative was evaluated. There was no significant difference in prognosis between patients with H0P0CY0 at the first SL and those with H0P0CY1 who were converted to CY-negative (p = .864) (Figure 3a). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in prognosis between the two groups who underwent surgery (p = .975) (Figure 3b). Of 68 patients who underwent radical surgery, 25 patients (37%) had recurrence, and seven patients died. The main pattern of recurrence was liver metastasis (56%). On the other hand, three of seven patients who underwent CS (43%) had recurrence after CS (Table 4). One patient had liver metastasis recurrence, and one had peritoneal dissemination recurrence. One patient had both liver metastasis and peritoneal dissemination recurrence and died.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated distant metastatic factors, including CY, by performing SL for patients with R-PDAC and assessed the efficacy of chemotherapy according to CY status. After exclusion of distant metastases on imaging by MDCT, EOB-MRI, and PET-CT, 8% of patients had gross distant metastases, and the proportion of H0P0CY1 patients was 19%, even among those with R-PDAC. In addition, the frequency of complications associated with SL was significantly low, which suggests that SL is useful and safe for the evaluation of distant metastatic factors in patients with R-PDAC.

Patients with distant metastases, including CY, had larger tumor diameters and higher levels of tumor markers in univariate analysis, similar to previously reported results,232426 whereas tumor diameter and body mass index were the only independent predictors in multivariate analysis. Furthermore, patients with H0P0CY1 were not significantly associated with higher levels of tumor markers in univariate analysis. In R-PDAC, tumor markers can predict micro H or P, but it may be difficult to predict only CY1. Although lower body mass index was a predictor of distant metastasis in the current study, it may have represented poor nutritional status, such as cachexia, but it could also be a bias derived from the small number of patients. While it may be preferable to perform SL in all patients with R-PDAC if possible, the results of this study strongly recommend SL in patients with larger tumor diameters. SL may also be considered for patients with lower body mass index and higher tumor marker values.

There was no significant difference in the number of days from EUS-FNA to SL or the localization of pancreatic cancer; thus, the risk of tumor cell leakage or seeding caused by FNA, as reported in a previous study,27 is likely to be low.

Diagnosing CY1 before introducing treatment enabled us to determine a suitable therapeutic strategy. The median survival of resected patients with CY1 at the time of resection was reported to be 17.5 months in a previous study,15 but in this study, the MST of all H0P0CY1 patients was extended to 24.2 months following systemic chemotherapy, implying that chemotherapy is effective. Therefore, upfront surgery is probably not recommended as described for peritoneal malignancy in two clinical practice guidelines.28, 29 Furthermore, patients who received systemic chemotherapy for H0P0CY1 and who were converted to CY-negative had lower CA19-9 levels before starting treatment. Notably, the prognosis of patients who were converted to CY-negative was similar to that of patients with CY0 at the initial diagnosis. In patients who could not be converted to CY-negative, liver metastasis was the main distant metastasis.

The presence of peritoneal dissemination has been shown to be closely associated with a poor prognosis in patients with PDAC.30 Nevertheless, there are only a few facilities in Japan, Europe, and the United States that perform SL to detect CY1, which is considered a preliminary stage of peritoneal dissemination. While prognosis has been studied in CY1 patients at the time of resection,15 there has been little evaluation before the introduction of preoperative chemotherapy. Satoi et al. reported the validity of assessing distant metastatic factors in SL in patients with UR-LA PDAC,5 but there has been no report focusing exclusively on R-PDAC, which is less advanced and more suitable for resection. Therefore, the results before the initiation of treatment, the frequency of distant metastatic factors, including CY, the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy, and the prognosis of CY-negative conversion patients with R-PDAC were not elucidated.

SL can detect distant metastatic factors that could not be detected by imaging evaluation, even in patients with R-PDAC. In addition, systemic chemotherapy for patients with positive CY can be performed to achieve CY-negative conversion and CS. The results of this study suggest that the rate of CY negative conversion and CS is relatively high, indicating that CY is easier to control than gross distant metastases such as liver metastases and peritoneal dissemination. Whether radical surgery should be performed for CY1 patients continues to be discussed,31, 32 but the current mainstream opinion is that upfront surgery should not be performed for CY1.33 On the other hand, CY-negative conversion and CS have been reported to possibly improve prognosis.34 SL is not yet widely performed, but it is a less invasive and safer procedure than resection surgery. We believe that confirming CY status by SL can help determine the appropriate systemic chemotherapy and possibly improve the prognosis.

There are several limitations of this study. First, it was a retrospective study based on single-center data, and may have included confounding factors and selection bias. Prospective studies will be needed in the future. Second, a small number of patients were included, and the follow-up period was relatively short. The median follow-up period was 13 months, which is insufficient to describe the long-term prognosis. Finally, most CY1 patients were treated with GnP for the first regimen, and no patients were treated with GS as standard therapy for R-PDAC. Patients who did not receive chemotherapy were also excluded from part of this study. Moreover, it is unclear whether CY-negative conversion is critical for resection, as there have been no patients in which surgery was performed without CY-negative conversion despite chemotherapy in our cohort.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, SL revealed distant metastatic factors even in patients with R-PDAC. Patients who converted to CY-negative as a result of systemic chemotherapy had lower CA19-9 levels, and the prognosis of patients who converted to CY-negative was not significantly different from that of patients with CY0 at the initial diagnosis. SL is effective in determining the appropriate chemotherapy and possibly results in improving the prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Katsuhisa Hirano, Kosuke Mori and Miki Ito for their expert support, and Yukino Kato for her excellent clerical support. The authors would also like to thank American Journal Experts (https://www.aje.com) for editing the draft of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.