Foot pain as first presenting symptom of renal cell carcinoma, due to metastatic lesion in medial cuneiform

Graphical Abstract

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) lesions in the foot are a rare entity and uncommon finding in a series of foot radiographs ordered to investigate foot pain. We report the case of a 72 year old male who experienced left foot pain for a year, before developing intermittent haematuria and right flank pain, and subsequently being found to have right RCC with an osseous metastatic lesion in the left medial cuneiform.

Abbreviations

-

- CT

-

- computed tomography

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

-

- RCC

-

- renal cell carcinoma

1 SUMMARY

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) lesions in the foot are a rare entity and uncommon finding in a series of foot radiographs ordered to investigate foot pain.

We report the case of a 72 year old male who experienced left foot pain for a year, before developing intermittent haematuria and right flank pain, and subsequently being found to have right RCC with an osseous metastatic lesion in the left medial cuneiform.

This case highlights the importance of the reporting radiologist considering metastatic disease in the differential for chronic foot pain. Diagnostic imaging workup and biopsy allowed for appropriate diagnosis and treatment in this case.

2 CLINICAL REPORT

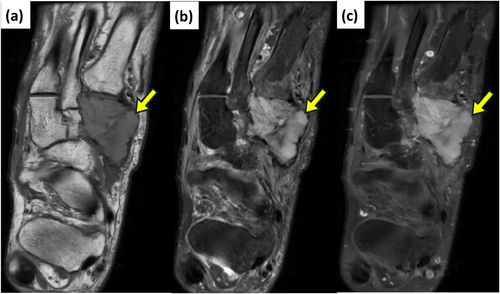

A 72 year old male had been experiencing left foot pain for about 12 months. Initial left foot radiographs were thought to be unremarkable, although in retrospect a subtle lucent lesion was apparent in the medial cuneiform (Figure 1). He subsequently developed symptoms of intermittent macroscopic haematuria and right flank pain, along with anorexia and weight loss. He has no other relevant medical conditions.

Initial left foot radiographs after symptom onset. Note the subtle lucency in the medial cuneiform without matrix calcification or periosteal reaction.

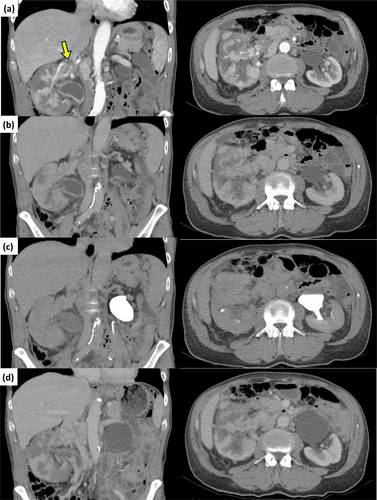

A contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a right renal mass with pathological regional lymph nodes and probable inferior vena cava (IVC) tumor thrombus (Figure 2). Left foot magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the same day confirmed an aggressive left medial cuneiform lesion with cortical breach and enhancing soft tissue component (Figure 3). He was referred to the Urology and Orthopedic outpatient clinics at our institution.

Coronal and axial CT abdomen contrast enhanced (a) arterial, (b) venous, (c) delayed phases, and (d) post contrast images, demonstrating the right renal mass and associated IVC thrombus (arrow). CT, computed tomography; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Left foot (a) axial T1, (b) axial PDFS, and (c) post gadolinium axial T1FS magnetic resonance images, demonstrating an expansile lesion in the medial cuneiform with cortical breach, replacement of marrow fat and enhancing soft tissue component.

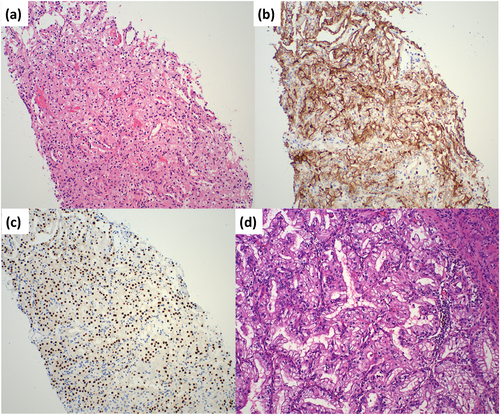

CT guided left foot core biopsy (Figure 4) and right renal mass biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC. Staging CT imaging revealed multifocal right renal carcinoma with direct invasion of the right renal vein/IVC and pathological regional lymphadenopathy, along with obstruction of the right collecting system.

(a) Photomicrograph of core biopsy of left foot showing a neoplasm composed of clear epithelial cells arranged in small nests and papillary structures (haematoxylin and eosin, magnification × 100). On immunohistochemistry, these cells demonstrate (b) CD10 membranous staining (magnification × 100) and (c) PAX8 nuclear staining (magnification × 100), in keeping with a diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. (d) Photomicrograph of representative section of tumor from the right nephrectomy, showing clear to eosinophilic cells with fine, arborizing vascularity and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, consistent with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (haematoxylin and eosin, magnification × 100).

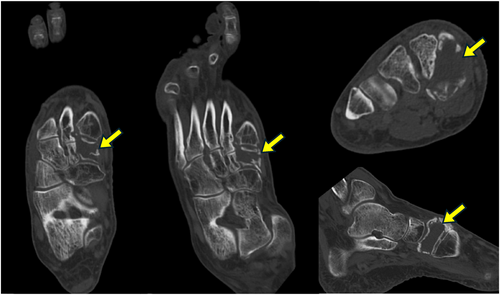

The patient subsequently underwent a right nephrectomy and IVC thrombus removal performed by the Urology Department, and 5 fractions of palliative radiotherapy to the left foot, with a total dose of 20.00 Gy, over 6 days performed by Radiation Oncology. He was commenced on dual agent immunotherapy with Ipilimumab and Nivolumab under the care of Medical Oncology. He was followed up in the Orthopedic outpatient clinic for his left foot lesion, with ongoing conservative management, as he is minimally symptomatic. His most recent left foot CT suggested partial collapse of the medial cuneiform without disease progression (Figure 5).

Left foot computed tomography images 2 years post radiotherapy demonstrating partial collapse of the medial cuneiform without disease progression.

3 DISCUSSION

Metastatic disease of the skeleton occurs in about 20%–30% of patients with malignancy, however metastatic disease to the hands and feet is extremely rare, which is somewhat surprising given the small bones of the hands and feet comprise more than half (106 of 206) of all bones in the human body [1]. Rates of metastases to the foot and ankle are less than 1%, with lung, colon and genitourinary tumors being the most common primary tumors [2]. In a retrospective analysis of 195 cases of foot tumors by Ajit Singh et al. published in 2024, 47 lesions were malignant, with 4 being metastases [3]. Often diagnosis of metastatic disease to the foot and ankle is delayed due to low clinical suspicion, and unfortunately the majority of acrometastases (lesions below the elbow and knee) are associated with disseminated malignancies, usually carrying a poor prognosis [4].

At initial diagnosis of RCC, abdominal CT remains the foundation of staging the primary tumour. The CT technique includes pre-contrast, arterial, nephrographic and delayed phase scans to identify hypervascular tumors and delineate arterial and venous structures [5]. Clear cell carcinoma demonstrates avid arterial enhancement as opposed to papillary or chromophobe subtypes, due to its vascularity. Clear cell metastases usually also demonstrate avid arterial enhancement, and can be undetectable in nephrographic phases, however other subtypes may enhance to a lesser degree and are better detected on nephrographic phases [6, 7]. Papillary lesions are hypovascular, and may appear cystic on one phase, but do show enhancement and washout. The nephrographic/portal venous phase is useful in examining the venous system to look for invasion, and for surgical planning. Delayed excretory phase images can be used to evaluate for extension into the collecting system, and for routine surveillance when there is clinical concern [5]. MRI can be used when iodinated contrast is contraindicated, or when further evaluation of soft tissue is required. Protocols should include gadolinium and non-contrast T1 sequences, and similar to CT, arterial phase imaging is useful in the detection of clear cell type metastases [6, 8]. It is also useful to show intravoxel fat and restricted diffusion; diffusion weighted imaging sequences should be included in the MRI kidney protocol to assist in tumor characterisation. 18F-FDG-PET/CT can be a useful adjunct in establishing metastatic lesions detected by CT, MRI or bone scan, however the physiological excretion of FDG in the renal pelvis limits the evaluation of small primary RCC [9].

Pulmonary metastases comprise 45% of metastatic RCC, and are usually asymptomatic [7, 8]. It is routine to perform chest CT with contrast to detect small pulmonary metastases. Bone is the second most common site of RCC metastases, with common locations including the pelvis, spine and ribs, and solitary bone metastases being rare. MRI can be more useful than CT in detecting smaller lesions, and lesions adjacent to bones [6, 9]. Bone scan is indicated for patients with bone pain or an elevated alkaline phosphatase level [10]. Lymph node metastases are the third most common site of spread in RCC, occurring in 22% of cases, with both CT and MRI being adequate in identifying metastatic lymph nodes [6]. Liver metastases are associated with a poor prognosis, with only 2%–4% of patients with metastatic RCC having operable liver metastases without additional sites of disease [6]. RCC has a low incidence of brain metastases, and brain imaging is usually reserved for those who have neurologic symptoms [9].

4 CONCLUSION

This patient's initial presenting complaint of foot pain is atypical, given the rarity of RCC metastasis to the bones of the foot.

This case highlights the importance of considering metastatic disease as a potential cause for chronic foot pain, particularly in those with systemic symptoms leading to a diagnosis of cancer.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christopher Kleimeyer: Project administration (lead); writing—original draft (lead). Stephanie Stoddart: Data curation (supporting); resources (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting). Simon Platt: Conceptualization (lead); supervision (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting). Craig A. Buchan: Supervision (lead); writing—review and editing (supporting).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr Mary-Ann Koh and Dr Sooraj Pillai, Pathology Queensland, Gold Coast University Hospital, for their assistance with the pathology figures. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. All authors have contributed significantly. All authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed patient consent was obtained.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.