Human–Wildlife Conflict or Human–Human Conflict? Social Constructions of Stakeholder Groups Involved in Wildlife Management in Northern Zimbabwe

人兽冲突抑或人际冲突?津巴布韦北部野生动物管理之利益相关方的社会建构研究

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

ABSTRACT

enConflicts between people and wildlife, often termed human–wildlife conflicts, are a global issue that can require complex solutions. However, another significant, frequently overlooked cause for concern within this context is the conflicts that can arise between stakeholders with varying interests, perspectives or goals regarding wildlife management and conservation. Such human–human conflicts can hamper the success of wildlife conservation initiatives outside protected areas. These conflicts frequently serve as proxies for the underlying socioeconomic and political tensions between stakeholders with divergent wildlife management goals. Using a social constructionist approach and a qualitative case study, this study investigates how diverse stakeholders—namely, agriculturalists, conservationists, foragers and safari operators—in Chapoto Ward, northern Zimbabwe, construct images of each other during conflicts over wildlife management. The findings reveal that stakeholder groups socially constructed one another as powerful outsiders, ignorant and inconsiderate, habitat destroyers and poachers, and uncaring, greedy and selfish. These social constructions were driven by differing agendas, beliefs, priorities and values regarding wildlife management, competing land-use activities, and socioeconomic and political interests. This study recommends that wildlife managers develop an objective understanding of the competing constructions of each stakeholder group and incorporate these insights into wildlife management policy and conflict resolution processes.

摘要

zh在野生动物管理方面, 常冠以“人兽冲突 (HWC)”之名的人际冲突已成为全球性治理难题, 严重制约着保护区外动物保护计划的有效实施。此类冲突的底层原因通常是具有不同野生动物管理目标的利益相关方之间潜在的社会经济和政治冲突。本研究基于社会建构主义方法, 通过定性案例研究揭示津巴布韦北部Chapoto Ward地区四类核心利益相关方 (农业从业者、环保主义者、偷猎者及狩猎经营者) 在野生动物管理冲突中如何建构彼此的形象。研究发现, 利益相关方相互建构了“有影响力局外者”、“无知冒进者”、“生态破坏与盗猎者”以及“冷漠利己主义者”四类形象。这种建构源于各群体在野生动物管理目标、竞争性土地利用活动以及社会经济政治利益诉求等方面中的不同议程、信念、优先事项以及价值观。研究建议野生动物管理者应搁置偏见, 理解各利益相关方之间相互抵牾的社会建构行为, 将思考成果纳入政策制定与冲突调解流程中。

简明语言摘要

zh在野生动物保护问题上的人际冲突往往反映了治理目标不同的利益相关方之间潜在的社会经济和政治冲突。在这些冲突中, 参与野生动物管理的不同利益相关方在构建彼此的形象。研究表明, 不同利益相关方之间的社会形象建构源于各群体在野生动物管理目标、竞争性土地利用活动以及社会经济政治利益诉求等方面中的不同议程、信念、优先事项以及价值观。研究建议野生动物管理者应搁置偏见, 理解各利益相关方之间相互抵牾的社会建构行为, 将思考成果纳入政策制定与冲突调解流程中。

Summary

enConflicts between people over wildlife often reflect deeper socioeconomic and political tensions between stakeholders with divergent wildlife management goals. Due to these conflicts, diverse stakeholders involved in wildlife management create images of each other. The study shows that these social constructions are driven by stakeholders' differing agendas, beliefs, priorities and values concerning wildlife management, as well as competing land-use activities and socioeconomic interests. The study recommends that wildlife managers work to objectively understand the competing constructions created by different stakeholder groups and incorporate their varying perspectives into wildlife management policy and conflict resolution processes.

-

Practitioner Points

- ∘

Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) is complex and should not solely be viewed as negative encounters between people and wildlife but also as clashes between stakeholder groups with differing perspectives on wildlife management.

- ∘

Understanding the opinions that diverse stakeholders have of one another and their intentions helps address the real issues driving the conflict, rather than simply focusing on the apparent HWC.

- ∘

Local communities should be actively involved in conservation efforts and conflict resolution to enhance the success of wildlife conservation initiatives.

- ∘

实践者要点

zh

-

人兽冲突具有多维复杂性, 不应简单归因于人类与野生动物的负面遭遇, 而应理解为持不同管理立场的利益相关方之间的结构性碰撞。

-

理解不同利益相关方在建构彼此形象, 有助于解决导致冲突的真正问题, 而不能只关注显著的人兽冲突。

-

本地社区应积极参与动物保护工作和冲突解决进程, 以提高野生动物保护计划的成效。

1 Introduction

Conflicts between people over wildlife, often termed human–wildlife conflicts (HWCs), are a global problem and hamper the success of wildlife conservation initiatives outside protected areas (Utete and Matanzima 2024). Redpath et al. (2014, 1) argue that using the term HWC to refer to the negative encounters between people and wildlife is “misleading”, while Peterson et al. (2010, 74) describe the phrase as “problematic”. Peterson et al. (2010, 79) argue that the term portrays animals as “conscious human antagonists” and “combatants against people”. In addition, Hill (2015) and Peterson et al. (2010) indicate that the HWC label masks the complex underlying conflicts arising from the different beliefs, goals, interests, priorities and values of stakeholder groups regarding wildlife management. In particular, the label conceals the underlying human–human conflicts (HHCs) between groups negatively impacted by wildlife and those defending wildlife conservation objectives (Hill 2015; Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2014). This is supported by Fraser-Celin et al. (2018, 341), who assert that HWC “can be understood better in terms of conflict between humans over wildlife”. Similarly, Ghosal et al. (2015, 273) posit that “treating so-called ‘human–wildlife conflicts’ exclusively as that (i.e., conflicts between people and animals) is a certain road to failure”. Thus, viewing HWC as a conflict between humans and animals masks the broader systemic drivers of HWC (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Madden and McQuinn 2014).

Peterson et al. (2010) and Redpath et al. (2014) argue that mislabelling these conflicts can aggravate the problems between people and wildlife and hinder conflict resolution. Furthermore, such framing results in wildlife managers prioritising the use of technical solutions to address the adverse consequences of human–wildlife interactions instead of addressing the underlying HHC (Dickman 2010; Hill 2015; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2014). However, technical solutions such as changes in livestock husbandry and compensation schemes have rarely achieved desired results as wildlife damage continues to escalate (Dickman 2010; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Rust et al. 2016). For example, Boitani et al. (2010) found that compensation schemes for the predation of livestock by wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy were unsuccessful in mitigating farmer–wolf conflict because they failed to address the underlying social conflict. Consequently, Peterson et al. (2010, 80) stress the need “to identify and address human–human conflicts masked by the human–wildlife conflict label”. Similarly, Redpath et al. (2014) and Young et al. (2010) highlight the necessity to clearly distinguish between the negative impacts of wildlife on people and their activities and the underlying HHCs between stakeholders with divergent wildlife management goals. This distinction would help identify the main adversaries involved in the conflict and enable conservation authorities to adopt effective and appropriate conflict mitigation strategies (Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2014).

Additionally, some authors have called for human–wildlife interactions to be understood in terms of how people perceive animals or assign symbolic meanings to them, as this influences how humans interact with certain species as well as understand human–wildlife relationships (Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005; Hill 2015). Hill (2015, 299) notes that “knowledge of different symbolic meanings of wild animals, their social importance, and how different groups use a particular species or wildlife construction to define or articulate an environmental problem is fundamental to understanding conflicts around wildlife”. This is supported by Fraser-Celin et al. (2018, 342) who posit that the social constructions of different animal species “reflect diverging agendas, priorities, values and feelings [among different stakeholders] that contribute to human conflict over wildlife”. These competing representations of animals are important because they help “to understand what the issue really is” and address the right problem (Pooley 2016, 516).

Building on the above, several authors (see Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Goedeke 2005; Jani 2024; Herda-Rapp and Marotz 2005) have examined competing stakeholder constructions of wild animals in attempts to capture the complexity of HWC. However, no known studies have investigated how diverse stakeholder groups construct images of each other. This study employs a social constructionist approach to explore the different images or meanings that diverse stakeholder groups in Chapoto Ward, in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, northern Zimbabwe, assign to each other. The aim of this study is to explore HHC over wildlife by documenting the social constructions of multiple stakeholders involved in wildlife conservation. Such a perspective helps holistically understand HWC within its social context (Dickman 2010; Madden and McQuinn 2014) and provides new insights into the issue. This study has three specific objectives: (1) to differentiate the stakeholders with different objectives regarding wildlife conservation, (2) to investigate HHC over wildlife by documenting different stakeholder groups' constructions of each other during conflicts over wildlife and (3) to examine the implications of these social constructions on wildlife management and human–wildlife coexistence.

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Social Constructionism

The social constructionist approach helps understand people's conceptions of nature and environmental issues (Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005). Social constructionists argue that people create their social worlds through social interactions that assign meaning to the environment (Harker and Bates 2007; Herda-Rapp and Marotz 2005; Scarce 1998). The varied meanings of nature created by social groups are instructive about human relationships with nature; they represent and shape how people think about nature and guide how people relate to it and interact with it (Greider and Garkovich 1994; Herda-Rapp and Marotz 2005; Scarce 1998). The multiple constructions of nature result in opposing definitions of landscapes (Greider and Garkovich 1994), animals (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Goedeke 2005; Jani 2024; Scarce 1998) and oceans (Hou 2022) within a single society. These multiple constructions of nature are often a source of social conflict over environmental and natural resource issues and are also important in resolving such problems (Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005).

In relation to animals, these multiple social constructions help understand stakeholders' competing interests, agendas, socioeconomic needs, priorities, opinions and perspectives regarding wildlife management (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Goedeke 2005; Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005; Hill 2015; Scarce 1998). For instance, the competing social constructions of the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) in Botswana by different stakeholders—agriculturalists, conservationists and tourism players—reflect the different groups' diverging values, feelings and priorities regarding the management of the species (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018). Similarly, Goedeke (2005) found that the competing social constructions of river otters (Lontra canadensis) by anglers, pond owners and otter protection activists in Missouri, USA, reflected disagreements over their management and appropriate conflict resolution strategies. In the same vein, Rikoon and Albee (1998) viewed the contrasting constructions of free-roaming horses (Equus ferus) in the Missouri Ozarks as symbolic of the power relations between residents and the National Park Service. Likewise, Scarce (1998) showed that for conservation authorities, wolves (C. lupus) symbolised power and control, while for residents bordering Yellowstone National Park, they symbolised self-determination and freedom. These competing constructions of wildlife species reflect the often-overlooked issues underlying the apparent conflict between people and wildlife (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018).

As stakeholder groups assign competing meanings to wildlife, they also create negative images of each other (Harker and Bates 2007). For instance, diverse stakeholders construct meanings of each other that reflect disagreement over wildlife management (Draheim et al. 2021). This was evident in the conflict over coyote (Canis latrans) management strategies in Denver, USA, where differing constructions of coyotes by various stakeholder groups involved in coyote management complicated the resolution of the conflict (Draheim 2012). Similarly, the black bear (Ursus americanus) hunt controversy in New Jersey involved the competing social constructions of bears, hunters, suburban homeowners, animal rights activists and state wildlife managers. The conflict became intractable because of the polarisation between the diverse stakeholder groups, with each group stereotyping the others (Harker and Bates 2007). Advocates of the hunt were described as “murderous, immoral, and barbaric”, while opponents were labelled as “idiots, wackos, and effeminate sorority sisters” (Harker and Bates 2007, 349). This polarisation was also evident in conflicts over wolves (C. lupus) in Norway, where rural citizens viewed the wolf as a symbol of the decline in rural traditions and the urban animal lovers' lack of respect for rural lifestyles. In contrast, urbanites viewed wolves as symbolic of “an authentic, wild nature” (Skogen 2017, 54). Consequently, rural communities blamed the powerful city people, including politicians, resource managers, scientists and environmentalists, whom they felt did not understand the impact of their policies on the rural way of life. The urban people were labelled as “city people” and “extremists” (Krange and Skogen 2011, 225).

In light of the above, this study employs a social constructionist perspective to explore how stakeholders in Chapoto Ward, in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, construct images of one another. These constructions reflect their divergent wildlife management goals and further entrench HWC.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Study Area

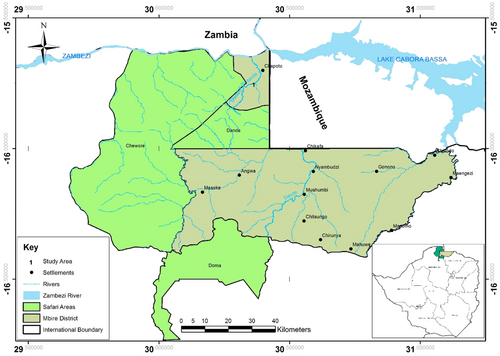

The study was conducted in Chapoto Ward, a dryland area in Mbire District (Figure 1) in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, northern Zimbabwe, from January to March 2018. Chapoto covers an area of 300 km2 and is bordered by Mozambique to the east and Zambia to the north, along the Zambezi River. It shares boundaries with the wildlife-rich Chewore and Dande Safari areas (Jani et al. 2019). The Mid-Zambezi Valley is characterised by low and variable rainfall, averaging between 350 and 650 mm/annum, and a mean annual temperature of 25°C (Chanza and Musakwa 2021). The area is covered by a deciduous dry savannah, dominated by Mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) (Chanza and Musakwa 2021), which provide local communities with ecosystem services, such as timber, fuelwood and construction materials.

Source: Author.

Chapoto Ward was chosen for this study due to its conservation significance, as it forms part of the Zimbabwe–Mozambique–Zambia (ZiMoZa) and Lower Zambezi–Mana Pools (LoZaMaP) Transfrontier Conservation Areas. It is also one of the first sites in Zimbabwe where the community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) initiative, represented by the renowned Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE), was initiated in 1989. The area has abundant wildlife because it shares immediate boundaries with the Chewore and Dande Safari areas. HWC is a significant issue in the area because wildlife species such as elephants (Loxodonta africana), buffalos (Syncerus caffer), spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) and lions (Panthera leo) share spaces with humans and livestock. Elephants also make incursions into the area from Mozambique and Zambia. Consequently, Chapoto Ward is an ideal location for examining conflict over wildlife, as HWC is a significant issue in the area.

In the Mid-Zambezi Valley, the expansion of agricultural land for cotton production, driven by human population growth, has led to wildlife habitat loss (Baudron et al. 2022). The authors indicate that a recent decline in cotton profitability, coupled with a shift to livestock farming, fuelled drastic land cover changes between 2007 and 2020. As a result, habitat loss has increased contact between people and wildlife, leading to negative interactions commonly referred to as HWC (Jani et al. 2020). The negative interactions include crop destruction, livestock predation, property damage, human injuries and deaths and restrictions on people's movement (Jani et al. 2023). Additionally, competing land uses and socioeconomic interests, such as cotton farming, conservation and safari hunting, have resulted in increased conflict between diverse stakeholder groups (Jani 2024). The reliance of local communities on forest resources, such as firewood, building materials, fruits, edible wild foods and honey, also increases their chances of coming into contact with wildlife (Chanza and Musakwa 2021; Jani et al. 2022).

The abundance of wildlife in the area supported the implementation the CAMPFIRE programme in 1989 as a pathway to potentially ensure human–wildlife coexistence (Tchakatumba et al. 2019). Under this initiative, the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management, now known as Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks), delegated wildlife management to Rural District Councils (RDCs). These councils market wildlife to international hunters on behalf of local communities neighbouring protected, providing economic benefits (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023; Tchakatumba et al. 2019). The rationale behind CAMPFIRE was to encourage local communities to develop a sense of ownership over wildlife resources and to use them sustainably, benefiting from conservation rewards (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023). RDCs have contractual arrangements with safari operators that facilitate controlled trophy hunting (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023; Jani et al. 2022; Matema and Andersson 2015). Through CAMPFIRE, local communities benefit from employment opportunities, game meat, drought relief and infrastructure development (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023; Tchakatumba et al. 2019). However, the failure to devolve authority over resource management to the subdistrict level has undermined CAMPFIRE. This has led to the capture of safari hunting benefits by local elites and an unfair representation of local citizens in decision-making processes (Jani et al. 2022; Matema and Andersson 2015). Furthermore, the programme has failed to resolve HWC, as the benefits from CAMPFIRE do not offset the costs of living with wildlife (Jani et al. 2023).

Chapoto Ward is populated by two ethnic groups, namely, the Chikunda (agriculturalists) and the Doma (former hunter–gatherers). It comprises five Village Development Committees (VIDCOs) divided into 24 villages. The VIDCOs are Chiramba and Mariga on the western side of the Mwanzamtanda River, inhabited by the Doma, and Chansato, Chiruhwe and Nyaruparo on the eastern side, populated by the Chikunda. According to the 2022 census, Chapoto Ward has 952 households and a total population of 3773 (Zimstats 2022).

Dryland agriculture and livestock rearing are the main livelihood activities in Chapoto. The Chikunda grow cotton as a cash crop and rear cattle (Bos taurus) and goats (Capra hircus). Both the Doma and the Chikunda grow maize (Zea mays) and drought-tolerant crops such as sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and millet (Pennisetum glaucum) in upland fields, and they also grow vegetables along the banks of the Mwanzamtanda River. The economic activities of the Doma also include pottery making, foraging for edible plants, gathering wild fruits, honey extraction, fishing, providing wage labour and illegal hunting, which is carried out clandestinely (Jani 2022).

3.2 Study Design

The philosophical positions that informed the qualitative research methodology employed in this study were constructionism and interpretivism. Snape and Spencer (2003, 3) define qualitative research as an “in-depth and interpreted understanding of the social world of research participants by learning about their social and material circumstances, experiences, perspectives, and histories”. Ontologically, constructionism posits that different people have multiple ways of understanding the world in which they live. Epistemologically, the paradigm postulates that knowledge is socially constructed through human engagement with the physical world (Scotland 2012).

HWC is a complex problem underlain by social conflict (Dickman 2010; Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005; Madden and McQuinn 2014). As such, a qualitative approach offers an in-depth understanding of the issues underlying HWC, such as emotions, relationships and values, as well as historical, cultural, economic and political factors (Rust et al. 2017). For this reason, the constructionist paradigm was deemed appropriate for this study, as the researcher aimed to explore how participants constructed varied images of each other, shaped by their divergent agendas, experiences, perspectives, priorities and values regarding wildlife management.

3.3 Sample Size and Data Collection

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Mbire RDC and local gatekeepers, namely, Chief Chapoto and the local Councillor. My positionality, which encompasses my identity, personal experiences and philosophical stance (Yip 2023), influenced my access to research participants. As a researcher from Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe, with no prior experience in HWCs and a limited understanding of the local culture, I held a position of relative power over the marginalised subsistence farmers, especially Doma participants, who were at the bottom of the social hierarchy. This power imbalance was mitigated by working closely with the local councillor and traditional leaders, as well as hiring two local male research assistants knowledgeable about the community's culture to assist with data collection. Over time, trust was built, and this power inequality was reduced through the influence of the research assistants, who helped establish rapport with the participants.

Before the interviews commenced, the researcher explained the purpose of the study, informed participants that they were free to withdraw at any point, guaranteed their anonymity, and also assured them of the confidentiality of their responses. Verbal consent was then obtained before conducting the interviews.

Data were collected through semistructured interviews, a focus group discussion, document analysis and participant observation. A sample population of 60 heads of households was selected from 952 households using systematic random sampling to respond to face-to-face interviews. The first household was purposively selected, after which households were selected at regular intervals. The Sampling Interval (SI) was calculated by dividing the total number of households by the sample size (SI = 952/60 = 15). Hence, every 15th household was selected for inclusion in the study. A small sample size was deemed sufficient because the study aimed for an in-depth understanding of the issues under investigation. A total of 39 male and 21 female participants were interviewed, and each interview lasted approximately one and a half hours. Interviews were conducted in Chikunda and Chidoma (a mixture of Chishona and Chikunda) and later translated into English. Data collection continued until no new information emerged from the interviews (Guest et al. 2006). This theoretical saturation helped to increase the transparency of the research findings. The interview guide was refined during a pilot study conducted in Matenhahunga Village in Chiruhwe VIDCO, which was not one of the sampled villages (Majid et al. 2017). The pilot study helped clarify any ambiguities in the questions, explore emerging themes, and determine the approximate duration of the interviews.

Twelve key informants, selected using purposive and snowball sampling for their expertise on the issues under investigation, responded to in-depth face-to-face interviews. Their selection was also based on their roles and positions held in the community, with assistance from the Chief and Councillor. These included the CAMPFIRE Association Director, a ZimParks official, a Mbire RDC official, the Chapoto Ward Wildlife Management Committee (WWMC) vice-chairperson, the Antipoaching Unit (APU) chairperson, the ward agricultural extension officer, a representative from a local nongovernmental organisation, the Lower Guruve Development Association, a Doma village head, a Chikunda village head, the Safari Operator (Charlton McCallum Safaris), and the local Chief and Councillor.

A focus group session was conducted at the Chapoto Business Centre with 10 discussants selected for their profound knowledge of the issues under investigation. The business centre was chosen for its convenience to participants from all five VIDCOs. The focus group included a member of the APU and WWMC, an ex-WWMC member, a Doma village head, a Chikunda village head, two Doma women, two Chikunda women, and a local agricultural expert. The participants were selected with the assistance of the Chief and Councillor.

Document analysis was also used to supplement the interview data. Documents gathered included the Parks and Wildlife Act, records of problem animal causality from the Mbire RDC, revenue records from consumptive tourism managed by the WWMC, and records of livestock predation, HWC injuries, and fatalities from the ward APU and the Mbire RDC. Additionally, the semistructured interviews were complemented by participant observation, which involved observing routine activities and attending VIDCO meetings. This approach helped to gain a deeper understanding of the local community's interactions with wildlife. The use of multiple data collection methods, including triangulation, enhanced the trustworthiness, credibility, rigour and quality of the research findings (Flick 2004).

3.4 Data Analysis

After interview transcription, the collected data were analysed inductively and thematically. This involved grouping the data into themes or categories to form a comprehensive picture of the participants' responses (Creswell 2009). The analysis followed the coding procedures suggested by Creswell (2009, 185–190), which included the following steps: preparing raw data files in Microsoft Word, carefully reading all the transcriptions to become familiar with the interview data, reading through the transcriptions multiple times to identify emerging themes, coding the data by classifying it into different headings or codes, grouping these codes into categories or themes, and refining the codes and categories by linking similar aspects. The categories reflected the meanings attributed to the diverse stakeholders. Relevant quotes from the interviews were selected to support the themes that emerged from the data. Participants were assigned pseudonyms to maintain anonymity and ensure confidentiality, in accordance with ethical guidelines (Creswell 2009).

4 Results

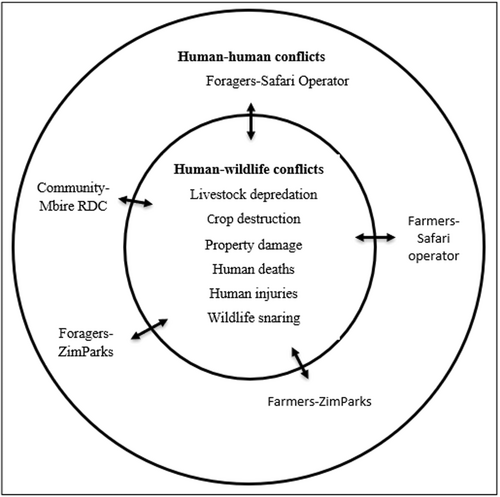

Stakeholder groups socially constructed one another in various ways, including as powerful outsiders, ignorant and inconsiderate, habitat destroyers and poachers, and uncaring, greedy and selfish. The stakeholder groups involved in these constructions are illustrated in Figure 2.

As indicated in Figure 2, HWCs often give rise to HHCs and vice versa. The inability of conservation authorities to address HWCs effectively can result in these conflicts evolving into disputes between local communities and the authorities. In turn, HHCs can escalate HWCs as local communities resort to retaliatory actions, such as snaring wildlife.

4.1 Powerful Outsiders

The local communities socially constructed the safari operators, ZimParks officials and Mbire RDC officials as “outsiders”. Led by their Chief, the locals expressed strong opposition to the imposition of the interests of “powerful outsiders”. They were particularly against the leasing of hunting concessions without their involvement and did not want “outsiders” to take the lead in wildlife conservation or in managing the CAMPFIRE programme. As one respondent stated: “Outsiders are taking a leading role in the management of wildlife at the expense of locals who share land with the animals” (Elderly Chikunda male respondent, Chiruhwe).

These outsiders should not control us. We should be consulted when hunting contracts are given to outsiders [safari operators]. The Council should show us the contract that was signed by the safari operator. Chiefs should also approve such agreements.

The local people's sentiments reflect their discontent with the lack of control over natural resources. This frustration stems from the conservation authorities' implementation of safari hunting in partnership with external conservation interests, such as safari operators, while local communities—who carry the burden of the challenges associated with living in close proximity to wildlife—are only minimally involved. As a result, these communities feel frustrated, marginalised, powerless and disempowered by the powerful elite who control decision-making. Residents are reminded that they have no de jure control over wildlife resources, as government structures are responsible for all decisions related to their management. This situation is further exacerbated by the devolution of authority over wildlife management to RDCs, instead of local subdistrict institutions.

4.2 Ignorant and Inconsiderate

“We report problem animals to the Mbire RDC, who then inform ZimParks. The problem is that they take a long time to respond to our reports. These parks people want to protect wild animals because they haven't seen what they do. They should come here to experience things and listen to what local people say. They do not care about our safety.”

(Middle-aged Chikunda male respondent, Chansato)

Most respondents cited the failure of the conservation authorities to respond to repeated reports of hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius) and elephants that destroyed crops along the banks of the Mwanzamtanda River and damaged a fence at the Chimata Irrigation Scheme. Participants felt that ZimParks and Mbire RDC officials were more interested in enforcing antipoaching laws and profiting from safari hunting than addressing the damage caused by wildlife. They also noted that conservation authorities ignored the dangers faced by the community, including the anxiety of potential wildlife attacks, the fear of crop destruction and the sleepless nights spent guarding crops. This was compounded by the lack of insurance or compensation for the communities affected by crop destruction, property loss, or even human injuries or death. As a result, damage-causing animals were viewed as problem animals belonging to the conservation authorities rather than as wildlife owned by the community.

When a game ranger was injured by a buffalo in November 2016, they rushed to take him to Mushumbi Pools District Hospital, which they never do when a local person is injured.

This example supports the local communities' claim that conservation authorities value wildlife over the safety and livelihoods of people. The residents felt that, since they lived with wildlife, the conservation authorities should devolve the responsibility of dealing with problem animals, along with the necessary resources, to the local APU, with the authorities maintaining an oversight role. In contrast, ZimParks believed that empowering communities to deal with problem animals would lead to abuse of the system, with people killing nonoffending animals for meat.

4.3 Habitat Destroyers and Poachers

The conflict between people and wildlife has intensified because of encroachment into wildlife habitats. The local people are to blame for the increasing conflict because they are expanding agricultural land without considering wildlife's shrinking habitat. If you live in the forest, you should know that wildlife also lives there. If they don't want to coexist with wild animals, they should move to other areas.

This sentiment reflects how conservationists disregarded the safety of local communities living near protected areas. The authorities failed to address the legitimate concerns of agropastoralists, framing the local people as insensitive intruders in wildlife territory. By doing so, they delegitimise the claims of agropastoralists, who viewed wildlife as a threat to their livelihoods and safety. This narrative also denied the vulnerability of these communities, portraying them not as victims of problem animals but as people deserving to be terrorised by wildlife.

Both the Chikunda and Doma participants expressed concern at the conservation authorities' stereotypical view of male victims of wildlife attacks as “poachers”, even though these individuals were attacked while performing everyday tasks, such as walking between villages, gathering firewood or going to the river for fishing. Participants noted that park officials only responded to reports of problem animals when a female was killed because women were not perceived as poachers. One participant remarked: “When a person is injured or killed by wild animals, they ask if it's a man or woman. Men are seen as poachers” (Elderly Doma male respondent, Mariga). Another participant lamented: “The fact that conservationists label us as poachers shows that we are not important. They do not appreciate our role in conserving wildlife on the ground” (Elderly Doma female respondent, Mariga).

Participants cited several examples of victims of wildlife attacks who were labelled as poachers. These included three Doma men killed by rampaging lions in 2010, a Doma man killed by a crocodile while fishing along the banks of the Zambezi River in 2013, a Doma man killed by a wounded buffalo while walking to Nyaruparo from Mariga in 2014, a Doma man killed by a leopard on his way to fish in the Zambezi River in 2015, a Chikunda man trampled to death by an elephant at Sawasawa Lodge, his workplace, in 2015, and a Doma man killed by a wounded buffalo while collecting firewood in 2016.

The conservationists' stance demonstrates a lack of concern for the safety of local people. The fact that the majority of victims of wildlife attacks were Doma allowed conservation authorities to label those attacked as poachers. Additionally, the Doma's foraging lifestyle and their involvement in clandestine hunting led to their being socially constructed as “illiterate”, “primitive”, “backward”, “consumers of bush foods”, “foragers” and “hunter–gatherers”. Consequently, their involvement in clandestine hunting resulted in them being physically assaulted whenever snares were found in the mountains bordering Chiramba and Mariga. This prompted the local communities to describe the conservationists as “cruel” for physically assaulting the Doma for alleged poaching without providing supporting evidence. The Doma argued that the conservation authorities failed to understand the impact of their “heartless conservation policies” on their foraging way of life. They also pointed out the hypocrisy of allowing professional hunters from outside the country to “kill animals for fun” while the people who lived alongside the wildlife were prohibited from hunting.

The labelling of the locals as poachers represents a perpetuation of the colonial legacy, where Indigenous communities were viewed as habitat destroyers, poachers and incapable of managing wildlife resources, while Europeans were positioned as protectors of wildlife. This paternalistic view places external actors or conservationists as the only authorities on wildlife conservation, further excluding Indigenous communities from decision-making and alienating them from the natural resources they supposedly have ownership over.

4.4 Uncaring, Greedy and Selfish

Local citizens described Mbire RDC officials as “uncaring” because they failed to provide financial assistance to victims of wildlife attacks. The RDC was supposed to pay USD300.00 in funeral assistance and cover hospital bills for fatalities and injuries caused by wildlife. However, participants revealed that the outstanding balances on funeral assistance and medical reimbursements date back to 2012. One respondent reported that the council only provided a coffin and failed to pay USD300.00 for the victim who was killed by a buffalo in 2016, citing a lack of funds. Another person injured by a buffalo in 2016 did not receive reimbursement for medical bills. This concern was raised by one respondent who said: “The RDC is misusing money allocated for victims of wildlife attacks. They always say there is no money, but this is provided for in the Council's annual budget” (Young Chikunda female respondent, Nyaruraro).

Participants also argued that the Mbire RDC was not using the 25% of trophy hunting revenue allocated for wildlife management and problem animal control (PAC), as sometimes the RDC made communities purchase ammunition for PAC. As one participant said: “The RDC tells us to source ammunition even though they receive money for PAC from CAMPFIRE” (Focus group discussion).

Furthermore, participants labelled RDC officials as “selfish” and “greedy” because they deprived local communities of game meat from PAC. The allocation of game meat to households had significantly declined due to the appropriation of meat for personal benefit by the elite, including politicians, Mbire RDC officials, the local ward Councillor and the Chief, who controlled decision-making. This was attributed to the recentralisation of wildlife resource governance, enabled by the government's appointment of local councillors as chairpersons of WWMCs. This shift led to the exclusion of local communities from participatory decision-making processes. Consequently, the apparent conflict between people and wildlife evolved into a conflict between local people and conservation authorities, which, in turn, fostered negative attitudes towards wildlife and protected area authorities.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study provide insights into the complex relationship between HHC and HWC, highlighting the profound complexities in addressing conflicts associated with wildlife conservation practices in rural communities. The findings support the argument that HWC should not be narrowly viewed as negative encounters between people and wildlife, such as crop destruction, livestock predation and human injuries or fatalities (Dickman 2010). Rather, it should also be understood as a conflict involving stakeholder groups with differing perspectives on wildlife management, which manifests as HHC (Dickman 2010; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2014). This dynamic was evident in Chapoto Ward, where the communities negatively impacted by wildlife clashed with ZimParks, the safari operator and the Mbire RDC, who were advocating for wildlife conservation objectives. Furthermore, these findings demonstrate the significant role that HHC plays in HWC, as emphasised by several researchers (Dickman 2010; Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2014). By bringing this to light, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of wildlife management.

The adverse human–wildlife interactions in Chapoto Ward were, in essence, surrogates for the competing socioeconomic and political interests of the various stakeholder groups, as well as the contrasting land uses. A key issue was the dominance of consumptive and nonconsumptive tourism, which competed with rain-fed agriculture and denied local people access to nature-based resources. This aligns with Fraser-Celin et al. (2018), who found that tensions between agriculturalists, conservationists and tourism stakeholders in Botswana regarding the conservation of African wild dogs emanated from competing socioeconomic and political interests. In Chapoto, these conflicts were also proxies for broader societal issues, such as the local communities' discontentment with their exclusion from decision-making processes related to wildlife management and the reduction of conservation benefits. Similar findings were reported in the Middle Sabi communities of Chipinge, southeastern Zimbabwe, where conflicts with conservationists arose from the exclusion of local communities from wildlife conservation efforts, the absence of compensation schemes, and the lack of inclusive stakeholder engagement (Mangiza and Chakawa 2024). In the same vein, in Binga, northwestern Zimbabwe, contestations over wildlife utilisation and control of wildlife resources, as well as a lack of participatory decision-making, led local communities to engage in illegal hunting and expand agricultural land into safari areas to protest their marginalisation (Muguti 2024). Likewise, Mariki et al. (2015) found that farmers in northern Tanzania killed elephants by driving them off cliffs to protest their marginalisation, powerlessness and disempowerment, as well as the lack of conservation benefits from the government.

The situation was further compounded by the failure of the conservation authorities to effectively deal with problem animals and disagreements over preferred conflict resolution strategies. Agropastoralists, who suffered crop and livestock losses, blamed the conservation authorities for their predicament, arguing that the failure to use lethal control measures to deal with problem animals was a key issue. In contrast, conservationists and safari operators involved in consumptive tourism argued that killing the animals would compromise trophy quality. Therefore, the local communities did not view the benefits from the CAMPFIRE programme as sufficient to offset losses caused by wildlife, particularly since ZimParks rangers were not effectively addressing the problem animals. This is supported by Matema and Andersson (2015), who found that tensions between conservationists and local communities in Mbire District, northern Zimbabwe, emanated from the perception that authorities prioritised wildlife conservation over dealing with problem animals that threatened local livelihoods and safety. Similar findings were reported by Marowa and Matanzima (2023) in Kariba, northwestern Zimbabwe, and in the Okavango Panhandle in northern Botswana by Noga et al. (2018), where local communities' frustrations with conservation authorities were exacerbated by the authorities' failure to respond quickly to reports of problem animal incidents. In Namibia's Kwandu Conservancy, Khumalo and Yung (2015) found that women expressed frustration and anger towards game guards due to delays in assessing crop damage, which delayed payment of compensation.

This study has demonstrated the existence of unequal power relations between conservationists and local communities. For example, the use of negative stereotypes and labels against local communities in Chapoto was intended to justify their exclusion from decision-making processes as well as to justify harassment for their involvement in the illegal exploitation of natural resources. In this context, powerful groups, namely, ZimParks, the Mbire RDC, and the safari operator, stereotyped agriculturalists and foragers, reinforcing their subordination. This issue was exacerbated by the restriction of local communities' access to wild resources by conservationists, who promoted the interests of private businesses (safari operators) in resource control. Similarly, in south-eastern Zimbabwe, conflicts between parks management and local communities arose from the lack of community engagement in conservation projects and their restricted access to natural resources (Dhliwayo, Muboko, and Gandiwa 2023; Dhliwayo, Muboko, Matseketsa, et al. 2023). This aligns with the argument by Matema and Andersson (2015, 94) that the apparent HWC is underpinned by “complex human–human conflicts over access to, and governance of, wildlife resources”. The stereotyping of local communities in Chapoto mirrors the labelling of the Maasai in Tanzania as “invaders” and “enemies of conservation”, which was used to legitimise the use of violence against them (Weldemichel 2020, 1497). The reinforcement of government ownership of wildlife is echoed by DeMotts and Hoon (2012), who argued that the control of elephants by the government in Botswana represented a loss of autonomy for communities affected by human–elephant conflict, resulting in antagonism towards both elephants and conservation authorities. Similarly, Mayberry et al. (2017) found that farmers in Botswana resented the government because they felt powerless relative to the conservation authorities as “owners” of elephants.

The different constructions of opposing stakeholder groups have helped to identify the interests involved in the conflict, as well as proffer appropriate mitigation measures. The fact that HWC was not only between humans and animals but also between human groups with conflicting agendas, priorities and wildlife management strategies, indicates that trying to minimise the negative impacts of wildlife through technical solutions is unlikely to resolve the conflict, as highlighted by Dickman (2010), Peterson et al. (2010) and Madden and McQuinn (2014). For example, the ineffectiveness of technical solutions was evident in Namibia, where farmers continued to report frequent livestock depredation by carnivores despite the translocation of problem animals, the use of livestock-guarding dogs and herders, and the killing of recurrent problem animals (Rust et al. 2016). This failure was attributed to wildlife managers not addressing the underlying social and economic inequalities arising from the unequal distribution of resources. Similarly, Fraser-Celin et al. (2018) found that technical solutions were unlikely to resolve human–carnivore conflicts in Botswana because they did not address the source of the human–human contestations. In the same vein, Matanzima (2024) found that technical measures were ineffective in solving human–lion conflicts in the Zambezi Valley, northwestern Zimbabwe, because local people believed that lions were sent by ancestors to punish them for quarrelling over the conducting of rituals. Likewise, Matema and Andersson (2015) argue that human–lion conflicts in Mbire District, northern Zimbabwe, could not be solved by technical solutions because predation by lions was seen as punishment from the ancestors for allowing outsiders to interfere in wildlife governance and for engaging in abominable activities. As indicated by Skogen (2017), using mitigation measures that do not address the underlying social conflict can increase tensions between stakeholder groups involved in the conflict. Therefore, this study supports the call by Peterson et al. (2010) to embrace alternative terms that accurately depict the real nature of the conflict, enabling more effective conflict mitigation measures.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge of the use of the social constructionist approach to understand HHCs over wildlife. It corroborates the findings of similar studies conducted elsewhere, which stress the importance of the social constructionist approach in understanding conflicts over wildlife management (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Goedeke 2005; Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005; Jani 2024). More importantly, the study highlights the significance of the relationships between stakeholder groups, their perceptions of one another, and how they interact and respond to HWC and efforts to manage it. Combining the social constructionist approach with a qualitative case study, this study provides rich insights into the competing social constructions by diverse stakeholders in Chapoto Ward, reflecting the deep-rooted social issues shaping conflicting views on wildlife management (Fraser-Celin et al. 2018; Goedeke 2005; Herda-Rapp and Goedeke 2005; Hill 2015). These issues are often overlooked as the drivers of the apparent conflict between people and wildlife (Dickman 2010).

Given that communities neighbouring protected areas bear the costs of conservation, they should derive wildlife-related benefits to promote human–wildlife coexistence (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023). However, Zimbabwe's CBNRM project (CAMPFIRE) has not succeeded in ensuring human–wildlife coexistence as originally envisioned. In Chapoto Ward, community support for the project is undermined by inadequate wildlife-related benefits and the lack of meaningful participation in decision-making processes, which contributes to hostility towards conservation authorities. This is compounded by the devolution of authority over wildlife management to RDCs instead of to subdistrict institutions (Jani et al. 2022). This, however, contrasts with Namibian conservancies, where communities are actively involved in managing their wildlife resources and retain 100% of the generated revenue because of a highly devolved governance model (Kansky 2022).

Furthermore, the recentralisation of control over wildlife resources by local elites, such as the councillor, Chief, political structures and conservation authorities, has culminated in the capture of CAMPFIRE benefits by these local elites. Similar patterns of elite capture have been reported elsewhere in Mbire District, northern Zimbabwe (Jani et al. 2022; Matema and Andersson 2015). This is compounded by the absence of a compensation scheme for wildlife-related losses. In contrast, Botswana and Namibia have established compensation schemes to address losses arising from HWC (Machena et al. 2017). Elite capture has also impeded the success of collective community forestry projects in India, where state and conservation organisations manipulated decision-making processes to co-opt benefits for personal gain, often at the expense of marginalised groups (Lund and Saito-Jensen 2013).

Therefore, this study calls for the reform of the CAMPFIRE programme to ensure the active participation of local communities in decision-making through the full devolution of authority over wildlife to subdistrict institutions. Such reform would enhance local ownership of the programme as originally envisioned, provide adequate wildlife benefits and more effectively involve local people in wildlife governance, thereby promoting sustainable human–wildlife coexistence (Noga et al. 2018).

Given the important role played by local communities in conserving wildlife outside protected areas, the government should initiate poverty alleviation programmes and collaborative approaches that reflect the diverse interests of the various stakeholder groups. For example, ensuring that local communities derive direct benefits from community-based tourism and granting them more control over natural resources would increase their tolerance for both wildlife and conservation authorities. In this regard, local communities should be involved from the planning phase and throughout the implementation of such projects (Dhliwayo, Muboko, Mashapa, et al. 2023; Mitincu et al. 2023). Furthermore, conservationists should align their goals with those of agriculturalists and foragers in ways that acknowledge their needs and socioeconomic interests (Manolache et al. 2020). Strategies could include identifying value-added practices in which the sustainable use of nature-based resources brings greater benefits to the foragers. Such measures would help foster long-term human–wildlife coexistence. Additionally, the development of integrated land-use management plans that consider the interests of ZimParks, RDCs, safari operators and local communities would enhance long-term conflict resolution.

Policymakers should also facilitate the involvement of all stakeholder groups in the mitigation of HWC by creating platforms for genuine consultation and open communication (Mitincu et al. 2023; Manolache et al. 2020; Noga et al. 2018). Strengthening participatory decision-making processes would help bridge competing social constructions, reconcile divergent stakeholder perspectives, beliefs, values and interests, and foster broader collaboration. During conflict reconciliation dialogues led by wildlife managers, conservationists, traditional leaders and RDCs, communities should actively participate in finding solutions to issues that affect them by freely voicing their concerns (Niță et al. 2023). Additionally, mediators should address both the proximate conflict between people and wildlife and the deeper social conflicts between stakeholder groups. Understanding the relationships and power dynamics between these groups is essential for identifying the root causes of conflict and promoting collaboration in seeking solutions (Mitincu et al. 2023; Niță et al. 2023; Pătru-Stupariu et al. 2020). Ultimately, incorporating alternative perspectives on resolving wildlife-related conflict could improve the likelihood of stakeholders reaching broadly supported, compromise-based solutions (Goedeke 2005).

6 Conclusion

This paper examined how diverse stakeholder groups—namely, agriculturalists, conservationists, foragers and the safari operator—in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, northern Zimbabwe, socially constructed one another. The findings showed that the social constructions were shaped by the groups' divergent agendas, beliefs, priorities and values regarding wildlife management, as well as by competing land-use activities and socioeconomic and political interests. The study has illuminated the broader social context in which HWC occurs and contributes to the growing recognition that such conflicts are underpinned by deep-rooted social, political and economic dynamics, and, thus, must be understood and managed as such. More importantly, the study demonstrated how the ways in which stakeholder groups construct each other further entrench HWC.

Therefore, the study underscores the need for the active participation of local communities in wildlife conservation and for greater collaboration between these communities and wildlife authorities to promote human–wildlife coexistence. By shedding light on the conflicting social constructions held by diverse stakeholder groups, this study offers valuable insights for conservation practitioners. In this regard, wildlife managers should seek to objectively understand these competing constructions and incorporate them into wildlife management policy and conflict resolution processes to develop more inclusive and effective mitigation strategies.

Author Contributions

Vincent Jani: conceptualisation, investigation, funding acquisition, writing – original draft, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, writing – review and editing, validation, supervision.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Chief Chapoto for the permission to conduct the research Chapoto Ward, the Nelson Mandela University Office of Research Development for funding this study and the people of Chapoto for responding to interviews.

Ethics Statement

Before undertaking the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Nelson Mandela University Sub-Committee for Ethics in the Faculty of Science.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.