The Primate Name Yòu (狖) and Its Referents: Implications for the Future Conservation of François' Langurs in China

灵长类动物名称“狖”及其指代对象再钩沉: 对中国黑叶猴 (Trachypithecus francoisi) 未来保护的启迪

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

ABSTRACT

enRethinking traditional animal names and their referents throughout history is important for understanding indigenous knowledge of wildlife, defining the role of animals in traditional cultures, and potentially promoting the conservation of species. The character yòu (狖) was the name of a nonhuman primate in ancient China. To date, yòu has been considered a gibbon (Nomascus spp.), a snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus spp.), or a François' langur (Trachypithecus francoisi). To better understand its original identity, I analyzed additional evidence to revisit the ideas and referents associated with yòu. Overall, identifying yòu as François' langurs is more consistent with historical archives. Historical records reveal that Fraznçois' langurs were widely distributed across South China in earlier periods. However, the species has since become extirpated from most of its primary habitats in the country. Reintroducing captive individuals into areas where François’ langurs were once found may be a key conservation strategy for restoring locally extinct populations and safeguarding this endangered species in the future.

摘要

zh重新思考历史演变中的传统动物名称及其指代对象对于准确理解野生动物的本土知识、更好解读动物在传统文化中的作用至关重要, 可能有助于推动物种的保护。汉字“狖”是古代中国的一种灵长类动物的名字。截止目前, 它被认为代指黑冠长臂猿属物种 (Nomascus spp.) 或金丝猴属物种 (Rhinopithecus spp.) 或黑叶猴 (Trachypithecus francoisi) 。为了更好地辨析其原始指代对象, 笔者对更为丰富的证据进行了分析, 重探了狖的指称与指称对象。结果表明古代文本中“狖”的原始身份最有可能为黑叶猴。同时, 历史记录揭示出在早期黑叶猴曾广泛分布于中国南方地区。但是随着时间推移, 该物种在中国已从其原有的绝大多数栖息地消失。未来将圈养个体重引入那些黑叶猴曾经分布的区域可能是恢复局部灭绝种群和拯救该物种的一项关键保护策略。

通俗摘要

zh动物的传统名称及其指代对象对于历史动物地理学研究具有启发意义。汉字“狖”是中国古代一种灵长类动物的名称。当下, 科学家与许多公众普遍认为这个名称指代金丝猴属动物 (Rhinopithecus spp.) 。在历史语言背景下, 本文通过对丰富证据的深入剖析, 重新探索了“ 狖”这一名称的观念和指代对象。笔者发现了古时“狖” 的最初且更加准确的语义值:狖为“黑猿”, 即黑叶猴 (Trachypithecus francoisi)。换而言之, “狖”的主流指代对象在历史进程中, 已从黑叶猴转变为了金丝猴。正如本研究所证明的, 在历史时期, 黑叶猴曾广布于中国的南方地区。不幸的是, 如今该物种在中国仅见于重庆市、贵州省和广西壮族自治区的部分孤立区域。因此, 在黑叶猴曾经分布的区域开展圈养个体的野外放归工作, 或将是未来拯救这一濒危物种的有用策略。

实践者要点

zh

-

相较金丝猴 (Rhinopithecus spp.) 或黑冠长臂猿 (Nomascus spp.), 黑叶猴 (Trachypithecus francoisi)更加可能是汉字“狖” 的原始指代对象。

-

历史记录揭示在较早时期, 黑叶猴曾经广泛分布于中国南方地区。

-

将黑叶猴圈养个体重引入至历史栖息地或将是未来拯救这一濒危物种的有用策略。

Summary

enTraditional animal names and their referents have implications for historical zoogeography. The character yòu (狖) was the name of a nonhuman primate in ancient China. Today, this name has often been interpreted as referring to snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus spp.) by scientists and members of the public. In this study, I analyzed additional evidence to revisit the meanings and referents of yòu in the context of historical language. I found the original and more accurate semantic value of yòu in ancient times refers to the black yuán (猿) or François' langur (Trachypithecus francoisi). In other words, the mainstream referent of the word yòu appears to have shifted from François' langurs to snub-nosed monkeys over time. As evidenced by this study, François’ langurs were widely distributed in South China in historical periods. Unfortunately, the species currently survives only in a few isolated areas in China, including Chongqing, Guizhou Province, and Guangxi Province. Hence, reintroducing captive individuals in regions where François' langurs were once found may be a useful strategy to conserve this endangered species in the future.

-

Practitioner Points

- ∘

François' langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) is more likely to be the original referent of the character yòu (狖) than the snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus spp.) or gibbon (Nomascus spp.).

- ∘

Historical records reveal that François' langurs were widely distributed in South China in earlier periods.

- ∘

Reintroducing captive individuals into areas where François' langurs were once distributed could be an important strategy to conserve this Endangered species in the future.

- ∘

1 Introduction

There is a complex relationship between names, concepts, and species identities from antiquity to the present day (Baker 2013; Aldrin 2016; Niu et al. 2022). In China, the corresponding relationship between primate names and their referents has varied over time. For instance, the referent of the Chinese character yuán (猿) has changed from François' langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) to the gibbons (Hylobatidae) known today (Niu et al. 2022). Rethinking traditional animal names and their referents throughout history is key to understanding indigenous knowledge of wildlife, explaining the role of animals in Chinese culture, and may help promote the conservation of species.

The character yòu (狖) is the name of a nonhuman primate in ancient China. In modern dictionaries, yòu means “a long-tailed black yuán mentioned in ancient works” (Ci-hai 辞海 1989). This character is composed of the semantic radical “犭—animal similar to a dog” on the left and the character “穴—cave” on the right. The pronunciations of this character were yòu or yù. Its variant forms include yù (㺠) and yòu (貁). From the character itself, the animal is inferred to have cave-dwelling habits (Niu 2023). Probably originating from Qu Yuan (屈原) (approximately 340–278 BCE), the traditional name yòu referred to primates in ancient China. van Gulik (1967) assumed that yòu is a dialectal character from the state of Chu, where Qu Yuan lived during the Warring States Period (476–221 BCE). Yuán yòu is a disyllabic form referring to the same animal as yòu (Shuō-wén-jiě-zì-xì-zhuàn说文解字系传: 狖,臣锴按:所谓蝯狖也).

Concerning the scientific identity of yòu, Liu (1954, 1980) regarded yòu as the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana). This view has evidently been accepted by several subsequent modern scientists (e.g., He 1988, 1991, 1993; Li et al. 1989, 2002; Wen 2003, 2009; Zhang 2015). Unlike Liu's (1954) opinion, van Gulik (1967) inferred yòu as yuán (gibbons). However, he did not provide compelling evidence to support the interpretation of yòu as yuán, as the referent of yuán was misinterpreted as “ape,” especially gibbons, in early modern China (van Gulik 1967; Niu et al. 2022). More recently, Niu (2023) suggested that yòu very likely represented François’ langurs (yuán) rather than a snub-nosed monkey or gibbon, based on a small number of isolated conceptual descriptions. Nevertheless, there is a high risk of misinterpretation when attempting to understand the animal name–object relationship without sufficient consideration of conceptual interpretations that vary from author to author. To date, the species identity of yòu remains controversial. In this study, I analyzed pieces of historical evidence more deeply relevant to traditional understandings of yòu to clarify its original identity.

2 Methodology

In this study, my methodology consisted of four parts as follows. First, I located the “species” in their historical context to analyze historical evidence based on scientific knowledge in primatology. Such an analytic procedure is a methodology of colligation, which involves placing one event into its historical context, tracing its internal relationship with other events, and ultimately forming a cohesive and coherent interpretation of historical issues (Qu et al. 2013; Niu 2023). Second, I analyzed reminiscence poems written about the great Chinese poet Li Bai (701–762 C. E.) by later poets and discovered robust cultural evidence to identify the original referent of yòu. Third, since 2008, I have carried out direct observations of R. brelichi, T. francoisi, and Hoolock tianxing during several field visits. This study provided direct observations and scientific data, such as vocal data and information on sleeping sites, which helped to better understand the traditional knowledge regarding these primates. Finally, in January 2025, I visited the Lingyin Feilai Peak Scenic Area in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China (Figure 1). The objective was to evaluate the reliability and validity of the historical data on primates in the Feilai Peak karst forest recorded in historical archives.

3 Analyses and Results

3.1 Yòu as a Cave-Dwelling Species

There are several historical texts that describe the cave-dwelling habits of yòu. A tale about the swordswomen Nie Yinniang (聂隐娘) tells readers about her huge living cave where many yuán yòu dwell (vol. 194, Tài-píng-guǎng-jì (太平广记)). The poet Yang Shen (杨慎) (1488–1559) writes that “left and right are all the caves of yuán yòu (左右猿狖穴).” Liang Youzhen (梁有贞) of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) heard “howls of the yuán yòu in the Yellow Dragon cave (黄龙洞深猿狖号)” at Mt. Luofu in Guangdong Province (Figure 1). Describing the mountains and rivers in Taiping Fu (太平府, which mainly corresponds to modern time Fanchang District, Wuhu City, Anhui Province, Figure 1), Gǔ-jīn-tú-shū-jī-chéng (Fāng-yú-huì-biān, vol. 811 (古今图书集成·方舆汇编, 第八百十一卷)) states that the yuán yòu lodge in caves on high cliffs (山椒石壁数十仞…猿狖穴之).

Based on the evidence above, the cave-dwelling habit of yuán yòu or yòu is consistent with the biological habit of François' langurs and the structure of the character yòu (狖). In the Dà-qīng-yī-tǒng-zhì (大清一統志), “Yuán Ridge (猿岭)” in Fengchuan the area (modern Fengkai County in Guangdong Province, Figure 1) is named because of “yuán yòu in the hill (猿狖所居)”. The yuán in this hill dwell in caves (山猿穴处泻飞泉, see Meng Yaozuo's Yuán-lǐng-fēi-quán in the Ming dynasty). All these historical records related to yòu are consistent with the cave-dwelling habits of François' langurs or yuán (Grueter and Ding 2006). Conversely, modern primatological studies have not reported findings of gibbons or snub-nosed monkeys in caves. In line with van Gulik (1967) inference, (yuán) yòu represents the same animal as yuán (Trachypithecus francoisi).

3.2 Yòu Fur Color

In terms of the fur color, the black yòu is often recorded in ancient works. Zhang Qi (张琦) of the Ming dynasty observed that the black yòu raided fruits (玄狖入偷杮霜). Tang Xianzu (汤显祖) (1550–1616) recorded black yòu occurring in the Zhenyang Gorge (玄狖接峰间) where yuán were often seen (Chen Yongyuan's Zhenyang Gorge (陈用原-浈阳峡); Qu Dajun's Guǎng-dōng-xīn-yǔ (屈大均-广东新语), Figure 1). Yǒng-lè-dà-diǎn (永乐大典) (vol. 2537) states, “the black yòu hang in trees (乔木挂玄狖).” However, one poem written by Guan Xiu (贯休) (832–912 C. E.) describes that “the yellow yòu is little (黄狖小)” (see “Pass by the Old House of Meng Haoran (经孟浩然鹿门旧居)”). This is consistent with the expectation that “yellow yòu” refers to the infant François' langur (Figure 2a). The emphasis on yòu as a type of black mammal (yòu: black yuán. see Yù-piān (玉篇), Zhèng-zì-tōng (正字通), Kāng-xī dictionary (康熙字典)) in texts above might stem from a temporary occurrence of yellow infants in langur groups, as the yellow individuals typically turn black at around 6 months of age. This biological variation may have influenced Li Shan's understanding of the color of yuán (Niu et al. 2022). Adult Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys are predominantly bright golden-orange, while newborns up to 1 year of age have light brownish-gray or light brown fur (Figure 2b). This color difference does not match that of yòu, further indicating that yòu is more likely to represent a François' langur rather than a Sichuan snub-nosed monkey.

In the Yún-nán-tōng-zhì (云南通志) (vol. 3), “Black yuán and yellow yòu (黑猿黄狖)” were recorded concurrently at Jijiao hill (犄角山) (which mainly corresponds to modern time Bijia hill (笔架山) in Daguan County (大关县), Zhaotong City) in northeast Yunnan Province, adjacent to present-day Guizhou Province (Figure 1). At first glance, this might appear consistent with the color differences between adult male and adult female gibbons (Figure 2c). But as mentioned earlier, “yellow yòu” likely refers to the golden infant of the black Francois' langur (yuán). In the poem Mountain Spirit (山鬼), Qu Yuan mentioned that “yòu chirp in the evening (狖夜鸣).” This vocalization pattern corresponds precisely to the latest time of day when François' langurs have been observed vocalizing. In contrast, scientists have not documented gibbons in China singing at sunset or after nightfall (Niu et al. 2022).

Meanwhile, in another gazetteer, Dà-qīng-yī-tǒng-zhì (vol. 183), the authors note that “there are numerous yuán yòu (多猿狖)” at Jijiao Hill. Therefore, it is more likely that yòu (or yuán yòu) refers to the François’ langur inhabiting Jijiao Hill in Yunnan Province. In addition, this area is part of Mt. Wumeng (乌蒙山). Today, the François' langur can still be found in a small area of Mt. Wumeng in the south of Guizhou (Deng and Zhou 2018). Guizhou has long been associated with the presence of yuán yòu, dating back to the Tang dynasty. The Older Book of the Tang Dynasty (旧唐书) records: “Nowadays Bozhou, in the southwest of the Tang Empire, is very remote (from Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province). Yuán yòu are found there, and few people can reach that area (今播州, 西南极远, 猿狖所居, 人迹罕至).” Bozhou refers to modern-day Zunyi City in the north of Guizhou Province, where François' Langurs are still found today (Niu et al. 2016; Zhou and Huang 2021, Figure 1).

Based on the appearance, behavior, and distribution of (yuán) yòu, I suggest that (yuán) yòu represents a François’ langur rather than a Sichuan snub-nosed monkey or gibbon.

3.3 Yuán Yòu and Li Bai's Yuán

In Anhui province, the name of Chizhou City (池州) during the Tang dynasty was Qiupu (秋浦) (Figure 1). There were many yuán in that area (see vol. 10 Guì-chí-xiàn-zhì (贵池县志), Guangxu edition (光绪版), 1883). Li Bai composed the poem series Qiupu Songs: Seventeen Poems (秋浦歌十七首) and described yuán in four of them: “There are white yuán in Qiupu. They look like pieces of falling snow when yuán jump (秋浦多白猿, 超腾若飞雪)”; and “Howls of yuán sound sorrowful in the night in Qiupu (秋浦猿夜愁),” for example. These lines became classics, widely recited by poets in later generations.

Subsequent poets often reminisced about Li Bai in their nostalgic poems when visiting or passing through Qiupu. Wang Anshi (王安石) (1021–1086) wrote a poem to honor the memory of two great Tang poets, Li Bai and Du Mu, after hearing yuán vocalizing near the river in Qiupu (see Hé-wáng-wēi-zhī-qiū-pǔ-wàng-qí-shān-gǎn-lǐ-tài-bái-dù-mù-zhī (和王微之秋浦望齐山感李太白杜牧之)). Guo Xiangzheng (郭祥正) (1035–1113), in Composing poems to reply Qiupu Songs: Seventeen Poems (3rd) (追和李白秋浦歌十七首其三) wrote: “It is so cold that yuán yòu can rarely be seen in the mountains (山寒猿狖稀).” Peng Sunyi (彭孙贻) (1615–1673) wrote: “The Yuán yòu are full of sorrow at the front of Li Bai's memorial temple (李白祠前猿狖愁)” (see Five Nostalgic Poems (3rd) (五怀诗其三)). Unlike Wang Anshi's usage, both Guo and Peng referred to Li Bai's yuán using the term “yuán yòu” rather than the monosyllabic “yuán.” Once again, this cultural tradition supports the idea that yuán yòu represents the same animal as yuán—the François' langur.

3.4 Summary

This study clearly showed that yòu is more likely to be a François' langur than a snub-nosed monkey or a gibbon. The cave-dwelling habit of yòu was supported by textual evidence and is also consistent with the formation of the character yòu (狖) and the behavioral ecology of the François' langur. Yòu are mainly black, though it may occasionally refer to the yellow infant of the François' langur. The yuán (T. francoisi) in Li Bai's Qiupu Songs (秋浦歌) represents the same animal as yuán yòu described by later poets. Each of these major biological and cultural characteristics aligns with those of François' langurs. Thus, the François’ langur is most likely to be the original referent of yòu.

4 Discussion

4.1 Animal Name and Identity

The act of naming is among the most fundamental functions of language (Borkfelt 2011). Language shapes how scientists conceive of scientific activity (Gonzalez 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the identity of traditional Chinese wildlife names to avoid further confusion. This study concurs with the inference that yòu refers to yuán (van Gulik 1967; Jiang Liangfu's view in Cui and Li 2003). Yuán yòu is a disyllable that refers to the same animal as yuán or yòu. The original identity of yuán yòu is most likely the François’ langur. With the help of traditional animal names and their referents, historical data concerning specific animals from archival documents can contribute to an understanding of traditional culture and historical zoogeography.

4.2 Reinterpretation of Traditional Culture

François' langurs held cultural and religious significance in traditional Chinese society (Niu et al. 2022). Many written records in Chinese refer to yuán yòu or yòu. Unfortunately, this disyllabic name (yuán yòu) has generally been misinterpreted in modern China as two distinct monosyllabic names, each referring to a separate taxon (e.g., Liu 1980; Li et al. 1989; Wen 2009; Zhang 2015). For instance, Qu Yuan writes: “Mysterious is the deep forest, the place where yuán yòu dwell (深林杳以冥冥兮, 乃猿狖之所居).” In contemporary academic literature, yuán yòu in this sentence has often been interpreted as yuán (gibbons) and yòu (snub-nosed monkeys), rather than as a compound name (Liu 1980; Li et al. 1989; Wen 2009; Zhang 2015). However, a more accurate interpretation of this line is: “Mysterious is the deep forest, the place where François' langurs dwell.”

Yi Yuanji (易元吉) (ca. 1100), renowned for his paintings of yuán in ancient China, is also significant in this context. Some art historians record that the primate species observed by Yi Yuanji was referred to as yuán yòu (see Table S1 4–6 in Niu 2023). This study shows that yuán yòu is a compound word referring to François’ langurs in such texts. Meanwhile, the reinterpretation of yòu as the François' langur helps resolve van Gulik's (1967) question regarding why yòu came to mean “black monkey” in modern dictionaries (Ci-hai 辞海 1989).

Niu et al. (2022) argued that the primary referent of the word yuán shifted from François' langurs to gibbons in early modern China (1890s–1950s). In a similar way, the mainstream referent of the name yuán yòu (or yòu) changed from the François' langur to the snub-nosed monkeys recognized today, coinciding with the period when Chinese scholars began studying biology as a modern scientific discipline (Liu 1954; Niu et al. 2022). This study supports the idea that the corresponding relationships between traditional primate names and their mainstream referents may shift over time in China.

Looking ahead, it is essential to clarify the referents of other traditional animal names. Doing so will allow for more accurate reinterpretation of traditional species knowledge, which could potentially play an important role in supporting the biocultural conservation of wildlife in the future (Burton 2002).

4.3 Historical Distribution of Primates: Implication for Future Conservation

Historical records are a vital data source for comprehending the geographical distribution of mammals (Nüchel et al. 2018; Wan et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2021). For instance, several authors have focused on the role of historical records in mapping the past habitat of snub-nosed monkeys (Li et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2018). This is crucial for formulating effective strategies to safeguard their survival and promote conservation efforts. Nevertheless, the correspondence between traditional animal names and the actual species they refer to can evolve over time. Therefore, accurately identifying the species represented by names in historical texts is of utmost importance (Niu et al. 2022; Niu 2023). Currently, the referent of the traditional name yòu is often misinterpreted as snub-nosed monkeys. This misunderstanding has had a lasting impact on the understanding of the historical distribution of primates in China among modern researchers. I provide three case studies to illustrate how the identification of yòu changed has influenced authors’ interpretations of historical species distributions (in Chongqing City, Guangxi Province, and Zhejiang and Fujian Provinces; see Figure 1), and I discuss the implications for species conservation in China.

First, due to the misrepresentation of yòu as referring to snub-nosed monkeys, some researchers have suggested that snub-nosed monkeys once occurred in Mt. Jinfo (金佛山), Chongqing City (e.g., Liu 1959; Wen 2009, 2018, 2019; Figure 1). However, only François’ langurs were found there during field investigations between 1980 and 1991 (Zhang et al. 1992).

Second, a similar confusion occurred when researchers interpreted yòu in gazetteers from Guangxi province. For example, He (1993) described yòu as snub-nosed monkeys in Longshan County (now Mashan County; Lóng-shān-xiàn-zhì (隆山县志), 1938; Figure 1). However, the primate species that actually inhabits this karst region is the François' langur (Zhou and Huang 2021).

Third, a passage in the Geographic Records of Wu Kingdom (吴录·地理志) states: “There are a lot of yòu in Yang County, Jian'an City (now Jian'ou City (建瓯市) in Fujian Province, Figure 1). They resemble yuán but have visible nostrils, and when it rains, they use their tails to cover their nostrils. Yòu are also found in Linhai City (now Linhai County in Taizhou City, Figure 1) (建安阳县多狖, 似猿而露鼻, 雨则以尾反塞鼻孔。郡内及临海皆有之).” Based on this or similar descriptions, most researchers concluded that yòu referred to snub-nosed monkeys and believed that these monkeys once lived in Zhejiang and Fujian Provinces (Li et al. 2002; Nüchel et al. 2018; Wen 2018, 2019; Zhao et al. 2018). However, in a different source from adjacent Zhejiang Province (see Shen Yiji (沈翼机) and coauthors' Zhè-jiāng-tōng-zhì (浙江通志)), yòu is defined as a black yuán (Trachypithecus francoisi, Niu et al. 2022). Zhè-jiāng-tōng-zhì (vol. 104) states: “Yòu, black yuán, are abundant in the mountains (狖, 黑猿, 山中多有之)” in the Guiji (会稽or Kuaiji) region (now Shaoxing City; Figure 1). Between the two contradictory accounts discussed above, the historical evidence presented below supports the interpretation that yòu more accurately refers to François' langurs in both provinces.

According to the Bā-mǐn-tōng-zhì (八闽通志) and Fú-jiàn-tōng-zhì (福建通志) from the Qing dynasty, the François' langur (yuán), not the snub-nosed monkey, was the widely distributed primate species in Fujian Province (Niu et al. 2022). This is also supported by poetic records. During the Tang dynasty, several poets described the presence of yuán in Fujian Province. Dai Shulun (戴叔伦) (732–789 CE) wrote a poem titled “Listening to yuán with Cui Facao near the Jianxi River (和崔法曹建溪闻猿),” recalling hearing loud primate calls when traveling with a friend. Luo Luoxian (骆罗宪) of the Song dynasty wrote: “Yuán's calls from mountains of Fujian echoed in the moonlight (数声猿叫闽山月).” These accounts suggest that François’ langurs were widespread in Fujian province during the Tang and Song dynasties.

In northern Zhejiang Province, near Lingyin Monastery in Hangzhou City, Xianglin Cave (香林洞) and Huyuan Cave (呼猿洞) (Figure 3) are notable landmarks. According to a study by Niu et al. (2022), in ancient times, some poets observed François' langurs (yuán) in these caves. A field visit to the Lingyin Feilai Peak Scenic Area in January 2025 confirmed that Huyuan Cave, Xianglin Cave, Cold Spring, and Feilai Peak—as described in historical records—are authentic natural features (Figure 3a–c). These microhabitats are more suitable for François' langurs than for gibbons or snub-nosed monkeys. Regrettably, this once-thriving species has now vanished from the Feilai karst forests, leaving only historical echoes behind. Moreover, others wrote a few descriptive sentences about François' langurs in the south of Zhejiang Province. In Wenzhou City, Lu Ying (路应) (745–811 C. E.) wrote: “Yuáns' calls echoed from the deep cave (猿声响深洞)” (Figure 1). Lin Jingxi (林景熙) (1242–1310) recorded: “A thirsty yuán guided its young to drink from a stream (渴猿引子下饮涧).” In Taizhou City (台州市), yuán and golden yuán (金丝猿) were recorded in Zhè-jiāng-tōng-zhì (浙江通志) (vol. 105). The behavior and coloration of these animals align more closely with François' langurs. However, a few authors have misinterpreted yòu as referring to snub-nosed monkeys in these classical texts (see also Gao You's (高诱) Huái-nán-zǐ-zhù (淮南子注)). Such misinterpretations diminish the reliability of historical data, especially when trying to understand species extinction dynamics.

This particular case of misreading yòu suggests that even sincere interpretations by ancient scholars could stray from the original intent. Considering the value of these ancient texts, modern researchers should adopt a more cautious and analytical approach. Instead of accepting earlier readings uncritically, we must engage more deeply with the source material. Tan (1982) offers several valuable suggestions for handling historical documents in geographical research; for example, avoiding premature conclusions based on limited evidence and not blindly accepting traditional interpretations of ancient literature. These recommendations are not only relevant to historical zoogeography but are also highly beneficial for the study of the historical relationship between animal names and their identities.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates the complex relationships between yòu as a name, concept, and referent from antiquity to the present day. According to my analyses, the traditional identity of yuán yòu or yòu is most likely to be a François' langur (yuán). The character yòu (狖) in traditional texts can carry one of two semantic values: the main and true semantic value (as the François' langur) or the false semantic value (as the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey). In this case, synchronic ideas and identities of yòu in traditional literature were eventually shifted to a mainstream understanding of yòu as Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys in the modern era. Therefore, researchers must consider the implications of the sociocultural and linguistic foundations for species identification of primate names found in historical discourse when conducting studies on historical zoogeography in the future. As emphasized by Niu et al. (2022), in the postcolonial era, clarifying traditional animal names and their corresponding referents (and associated ideas) has become a crucial step. This process is integral to decolonizing knowledge and fostering a more inclusive approach to wildlife conservation in numerous countries (e.g., Rubis 2020; Niu et al. 2022; Bezanson et al. 2024).

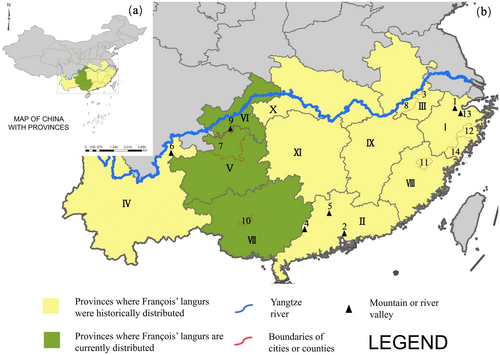

Considering the varying thoughts and identities of yòu in ancient China, researchers must be very careful when using the name yòu to extract historical records from official or formally documented histories and local gazetteers as scientific data, especially when revisiting the temporal and spatial dynamics of primate species. The François' langur was once widely distributed in South China during historical periods (Figure 1: This study: Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, Yunnan, Anhui; Niu et al. 2022; Niu 2023: Guangxi, Guizhou, Chongqing City, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Hubei, Hu'nan). Regrettably, in China, the species now exists only in a few isolated areas in Chongqing, Guizhou Province, and Guangxi Province (see Figure 1, Zhou and Huang 2021). Hence, reintroducing captive individuals to areas where François' langurs were once distributed might be a vital strategy to restore locally extinct populations and help conserve this endangered species in the future.

Author Contributions

Kefeng Niu: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mr. James Dopp and Mr. Cao Yuanming for their linguistic assistance on an earlier version of this manuscript. I express my sincere appreciation to Mr. Xiao Zhi for his assistance in map preparation. I am deeply indebted to the handling editor and four anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The author has nothing to report.