Diversity and Ecological Factors Influencing Medicinal Plant Use Among Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Philippines

21世纪菲律宾人类文化语言学族群药用植物多样性及其生态关联研究

Krizler C. Tanalgo and Yalaira Plang contributed equally to the manuscript.

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

ABSTRACT

enMany human populations rely on natural remedies for health and healing, with traditional medicinal plants playing a vital role in diverse ethnolinguistic cultures and contributing to biodiversity conservation. Research and conservation efforts to integrate traditional knowledge into healthcare are vital for preserving this heritage and for promoting sustainable healthcare in the Philippines. However, many of these systems are increasingly threatened by rapid environmental changes. In this study, we performed a nationwide synthesis to understand the diversity, distribution, and relationship of traditional plant use among various ethnolinguistic groups. We identified at least 796 plant species from 160 families and 65 orders that were utilised by 34 ethnolinguistic groups to treat 25 disease types. Our findings revealed a strong relationship between linguistically similar groups, indicating that geographical proximity, linguistic background, shared cultural practices, and environmental factors collectively influence medicinal plant use patterns among different groups. Furthermore, we developed the Species Use Priority Importance (SUPRIM) indicator to assess the priority level of plant species based on their use among ethnolinguistic groups and disease types. Factors such as the availability of healthcare facilities, proximity to roads, educational facilities, and tree density were significantly associated with higher SUPRIM indicator values. We posit that, despite modernisation and rapid development in the Philippines, the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their environment continues to shape the value of medicinal plant species within communities. Our findings further highlight the need for conservation efforts in indigenous lands that prioritise cultural protection and integrate ecological sustainability.

摘要

zh人类诸多族群至今仍依赖自然疗法维持健康与治疗疾病。传统药用植物在多样化的人类文化语言学文化体系中占据核心地位, 并对生物多样性保护具有重要贡献。将传统医学整合至现代医疗体系的研究以及对其的保护工作, 对于菲律宾民族遗产传承及促进可持续医疗发展具有关键意义。然而, 剧烈的环境变迁对传统医疗体系的威胁日甚。本研究在菲律宾进行全国性综合分析, 探讨不同人类文化语言学族群在传统药用植物利用的多样性、分布特征及其关联机制。研究发现34个人类文化语言学族群利用160科65目共计796种植物治疗25类疾病, 证实语言相近群体间存在显著的关系, 揭示出地理邻近性、语言背景、共有文化习俗及环境要素共同塑造了药用植物的利用模式。本研究创新性构建“物种使用优先重要性指标” (SUPRIM), 依据各族群的利用情况和所治疗的疾病类型对药用植物进行优先级评估。结果显示医疗设施可及性、道路邻近度、教育设施可用性及林木密度与高SUPRIM值呈现显著相关性。我们认为, 在菲律宾的快速现代化进程中, 本土居民与环境的内在联系仍然持续影响着社区对药用植物价值的认知。研究成果进一步强调需以文化保护为核心, 结合生态可持续性发展, 推进本土居民的土地保护工作。

简明语言摘要

zh许多人类社区仍然依赖传统药用植物来维持健康和治疗疾病;然而, 这些实践日益受到环境发展和全球变化的威胁。我们在菲律宾的全国性研究发现, 34个人类文化语言学族群使用796种药用植物治疗25种疾病, 使用情况受到语言, 文化以及环境的综合影响。研究成果强调了保护环境和文化传统的必要性。保存传统医学知识并将其纳入医疗保健体系, 有助于确保此类有价值的疗法继续造福子孙后代。

Summary

enMany human communities still rely on traditional medicinal plants for health and healing; however, these practices are increasingly threatened by environmental development and global changes. Our study, conducted across the Philippines, found that 34 ethnolinguistic groups used 796 plant species to treat 25 diseases, with plant use influenced by language, culture, and the environment. Our findings highlight the need to protect both environmental and cultural traditions. Preserving traditional knowledge and integrating it into healthcare systems can help ensure that these valuable practices continue to benefit future generations.

-

Practitioner Points

- ∘

This study delves into the patterns of traditional medicinal plant knowledge in the Philippines and identifies 796 plant species used by different ethnolinguistic groups to treat various diseases.

- ∘

Factors such as healthcare access, road proximity, availability of educational facilities, and forest cover influence the patterns of medicinal plant use among ethnolinguistic groups.

- ∘

This study emphasises the importance of preserving both ecosystems and indigenous knowledge, calling for further research, funding, and the inclusion of more ethnolinguistic data.

- ∘

实践者要点

zh

-

这项研究深入研究了菲律宾传统药用植物知识的模式, 并确定了不同人类文化语言学族群用于治疗各种疾病类型的796种植物。

-

医疗设施可及性、道路邻近度、教育设施可用性及林木密度等因素影响着人类文化语言学族群中药用植物的使用模式。

-

这项研究强调了保护生态系统和本土知识的重要性, 呼吁展开进一步的研究和资助以及收集更多的人类文化语言学数据。

1 Introduction

Indigenous Peoples have a rich history of using medicinal plants for healing purposes, drawing on centuries of traditional knowledge passed down through generations (Gurib-Fakim 2006). A deep understanding of local ecosystems and plant biodiversity has enabled the identification and utilisation of a wide array of plant species for various medicinal purposes. Traditional medicine, particularly in areas with limited resources, is often the most cost-effective and accessible form of healthcare in primary care systems (Bodeker and Kronenberg 2002; Sen et al. 2011; Wardle et al. 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO 2019) defines traditional medicine as ‘diverse health practices, approaches, knowledge and beliefs incorporating plant, animal and/or mineral based medicines, spiritual therapies, manual techniques and exercises applied singularly or in combination to maintain well-being, as well as to treat, diagnose or prevent illness’.

These traditional healing practices are often deeply intertwined with cultural beliefs, rituals, and holistic approaches to health and wellness (Balick and Cox 2020). Indigenous healers typically possess detailed knowledge of the properties and uses of medicinal plants, including the preparation and administration of effective treatments (Halberstein 2005; Gurib-Fakim 2006) for a wide range of ailments, including digestive, respiratory, skin infections, and spiritual or emotional imbalances (Halberstein 2005; Rubio and Naive 2018). Furthermore, indigenous medicinal plant use emphasises sustainable harvesting and conservation practices, ensuring that natural resources are managed responsibly to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem health (Bodeker and Kronenberg 2002; Fitzgerald et al. 2020). Many indigenous cultures have traditional protocols and taboos regarding the gathering and use of medicinal plants, aimed at preserving these valuable resources for future generations (Rankoana 2022; Otang-Mbeng 2023). The use of medicinal plants by Indigenous Peoples reflects not only their profound understanding of the natural world but also their holistic approach to health and well-being. By preserving and supporting indigenous medicinal plant traditions, we can learn valuable lessons about sustainable healthcare practices, biodiversity conservation, and the importance of cultural diversity in shaping our understanding of health (Bvenura and Kambizi 2023).

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of indigenous medicinal plant knowledge within broader healthcare systems (Knapp 2019; Pironon et al. 2024). According to the WHO, approximately 80% of the population in developing countries utilises traditional medicine, with approximately 40% of pharmaceutical products derived from nature and discovered through indigenous knowledge (WHO 2019). Collaboration between indigenous healers and modern medical practitioners has led to the validation of traditional remedies and the development of new treatments derived from indigenous plant knowledge (Kumar et al. 2021).

In the Philippines, there are at least 143 ethnolinguistic groups (De Vera 2007; Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino 2016), constituting approximately 10%–20% of the nation's population of 117.3 million (Data Commons 2025). These groups are primarily located in Mindanao (63%), followed by Luzon (32%) and the Visayas (3%), occupying approximately 13 million hectares of the national land territory (United Nations Office for Project Services 2023). The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) lists Igorots, Caraballe groups, Dumagats, Aetas, Mangyan, Ati, Tumanduk, Palawan groups, and other major Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines. Additionally, other ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, particularly the Moro people, are chiefly distributed in the southern part of the country, composed mainly of the Maranao, Tausug, Samal, Bajau, Yakan, Ilanon, Sangir, Melabugnan, and Jama Mapun (Minority Rights Group 2023). Historical and contemporary records have shown the high dependence of many Philippine cultural communities on traditional plant medicines for healing (Dapar et al. 2020; Cordero et al. 2022). Moreover, despite advancements in modern medicine, many Filipinos, particularly those in remote or marginalised communities, continue to rely on traditional healing practices, highlighting the enduring significance of indigenous knowledge in the Philippines' cultural landscape (Agapin 2020; Dapar et al. 2020; Rubio and Naive 2018).

However, the accelerating pace of deforestation and encroachment into protected and pristine areas of the Philippines poses a threat to human communities that depend on forest resources, including traditional medicine (Carson 2018; Global Forest Watch 2022; Agduma et al. 2023). The relentless expansion of human activities, driven by factors such as agriculture, logging, mining, and urbanisation, is rapidly eroding human-nature connections (De Vera 2007; Camacho 2016; Santini and Miquelajauregui 2022). As forests are cleared and habitats are fragmented, Indigenous communities face displacement, and countless plant and animal species teeter on the brink of extinction (Fernández-Llamazares et al. 2021). Moreover, encroachment threatens to extinguish the invaluable traditional knowledge held by these communities, which is intricately intertwined with the land and its resources (Berkes et al. 2000; Cámara-Leret et al. 2019). This includes century-old practices for sustainable resource management, medicinal plant usage, and ecological wisdom (Carson 2018). Thus, the loss of forests not only imperils the physical environment and its inhabitants but also risks the irreparable loss of a rich cultural heritage and centuries of accumulated wisdom.

While this human-nature connection has been significant for centuries, consolidated knowledge of the diversity patterns and extent of traditional medicinal plant use in the Philippines has not been thoroughly explored (Carag and Buot 2017; Magtalas et al. 2023). This is particularly true with respect to species ecology, conservation status, and socioecological drivers of medicinal plant use, which warrant a comprehensive synthesis. This study aims to understand the patterns, predictors, and priorities of medicinal plants used by ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines based on publicly available information from field surveys and assessments. We specifically aim to: (i) evaluate research efforts on traditional plant use among ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, (ii) analyse the relationship between species diversity, ecological status, ethnolinguistic affiliation, and medicinal use, (iii) identify species priorities based on ethnolinguistic and medicinal significance, and (iv) examine the correlation between priority levels and socioecological variables.

As indigenous knowledge continues to decline amid global environmental changes (Cámara-Leret et al. 2019), this synthesis seeks to enhance our understanding of traditional medicinal plant use in the Philippines. By addressing this knowledge gap and consolidating available information, we can effectively guide conservation efforts and inform policies related to cultural preservation, healthcare, and indigenous rights. Ultimately, this study highlights the intricate connections among culture, biodiversity, and sustainable development in the Philippines.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Synthesis Approach

We employed an integrative biodiversity synthesis approach, combining knowledge and utilisation of traditional medicinal plants among ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, based on publicly available information from 2000 to 2023. We then integrated this information with the conservation and ecological status of traditional plant species to identify key groups for future conservation efforts. This study covers the entire Philippines and focuses on seven (7) major ethnographic regions delineated by the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA). These regions include the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), Regions I, II, and III, the rest of Luzon, the Island Groups, the Visayas, Southern and Eastern Mindanao, Central Mindanao, and Northern and Western Mindanao (Cariño 2012; Dapar and Alejandro 2020). Additionally, the Bangsamoro people of the Philippines were included, specifically in the Palawan and Mindanao-Sulu regions.

2.2 Species Data

All literature search methods and data used for this analysis were sourced from the Herbolario v. 1 database (Plang et al. 2024). We standardised our data sampling based on published literature available through Google Scholar, although we acknowledge that we may have missed data available in other repositories not accessible through our platform (Plang et al. 2024). Within the database, we categorised our data according to ethnolinguistic group, year of publication, geographical distribution, taxonomic classification of plant species (e.g. families and orders), conservation status, and disease group classification according to the World Health Organization (WHO 2019). We classified the ethnolinguistic groups following the identification of article authors and counter-curated them using the Indigenous Peoples census from the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (2016), Philippine Statistics Authority (2020), and Reyes (2017).

The geographical distribution of each data set was mapped, visualised, and categorised according to ethnolinguistic regions (see Dapar and Alejandro 2020) and geopolitical units. The latitude and longitude of the study locations or locations where plants were collected or documented were extracted from published studies. For sites lacking specific coordinates, we used the centroid coordinates of the closest town. We released the general latitude and longitude of the study area to safeguard the locations of sensitive species and indigenous communities that are at risk of exploitation, poaching and collection.

We then classified plant species at the family and order levels. Species names were matched with the Catalogue of Life database (COL 2024), and the names of dubious species were removed from the database. Species ecological statuses, such as Red List status and endemism, were determined using the latest version of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List (IUCN Red List 2022) and the Updated National List of Threatened Philippine Plants and Their Categories (DENR Administrative Order 2017-11 2017). Lastly, we classified the medicinal application of each plant species according to disease categories affecting broad human body organ systems (e.g. circulatory, reproductive, respiratory, gastrointestinal, etc.), based on the ICPC classification from Staub et al. (2015), to create a more organised and accessible classification of the data set. In our current analysis, we excluded information on plant part utilisation.

2.3 Socioecological Predictors of Plant Use

The broad-scale relationship between socioeconomic and ecological factors and the ethnomedicinal use of medicinal plants remains largely unexplored in the Philippines. We used georeferenced data to map the spatial relationships between proxies for socioeconomic and ecological status. For the ecological variables, we included tree density (1-km resolution) (Crowther et al. 2015), forest canopy height (Potapov et al. 2021), and protected area designation (UNEP-WCMC 2024). The socioeconomic variables considered included distance to main roads (Humanitarian Data Exchange 2024c), distance to health facilities (Humanitarian Data Exchange 2024b), and distance to education facilities (Humanitarian Data Exchange 2024a). We used QGIS (QGIS Development Team 2025) to map and quantify these ecological variables.

2.4 Species Use Priority and Importance (SUPRIM) Indicator

To assess the relative significance of plant species in traditional medicine use across ethnolinguistic groups and disease types, we developed a Species Use Priority and Importance (SUPRIM) indicator. This metric was developed to address the need for a standardised measure that captures the cultural and medicinal relevance of plant species. The SUPRIM indicator quantifies plant importance at the taxonomic level by considering two key factors. First, it accounts for the number of ethnolinguistic groups utilising a given species, and second, it accounts for the diversity of traditional medicinal applications associated with the plant species. By integrating these aspects, the SUPRIM indicator provides a holistic measure of a species' benefit in indigenous healthcare systems, helping to prioritise conservation efforts and inform policies on cultural and biodiversity preservation.

Consequently, the final SUPRIM indicator values range from 0.00 to 1.00, where values near 1.00 indicate higher levels of importance, meaning the species is widely utilised by many ethnolinguistic groups for many disease types.

2.5 Data Analyses and Visualisation

Kendall's τ-b analysis was used to determine the congruence between the number of studies per island group and the year of publication. We used the Chi-square test of independence (χ2) to determine the relationship between ethnolinguistic groups, taxonomic groups, and ecological status, including occurrence within protected areas of traditional medicinal plants and disease applications. We then analysed the percent similarity of traditional medicinal plants among ethnolinguistic groups using Bray-Curtis similarity analysis in PAST (Hammer et al. 2001).

We then compared the %Ethno, %Dis, and SUPRIM indicators according to IUCN conservation status (IUCN Red List 2022) and geopolitical endemism (i.e. species-restricted distribution in the Philippines) using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. We also performed a Spearman's correlation analysis between the SUPRIM indicator values and the mean values of the quantified socioecological variables to determine the relationship between the priority and importance of species and socioecological factors.

All statistical tests and data visualisations were performed using Jamovi version 2.28 (The Jamovi Project 2023), GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism 2022), and Scimago Graphica (Hassan-Montero et al. 2022). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Research Trends and Efforts

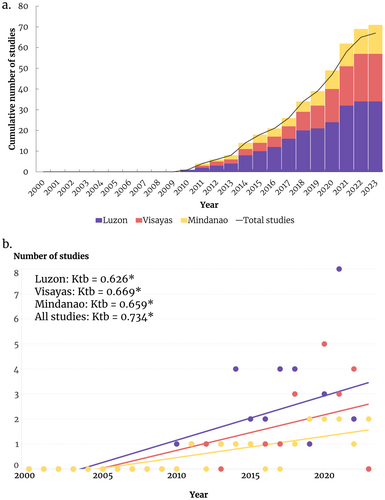

Our study collated 13,402 records of traditional medicinal plant use from 67 studies published between 2000 and 2023. Most of these records were from Luzon Island (n = 34, 48%), followed by the Visayas (n = 23, 32%), and Mindanao (n = 14, 20%). There was notable congruence in the number of studies per major island and the overall number of studies conducted over the 24-year period. However, the distribution of studies did not vary significantly among the major island groups in the Philippines (Kruskal-Wallis test: H = 1.810, p = 0.4045) (Figure 1).

3.2 Diversity and Ecological Status

We accounted for 796 plant species (including algae) from 160 families and 68 orders reported by ethnolinguistic groups as remedies for diseases and illnesses. Among these, the ten most widely represented families are Fabaceae (n = 57 spp.), Asteraceae (n = 48 spp.), Lamiaceae (n = 37 spp.), Poaceae (n = 30 spp.), Moraceae (n = 24 spp.), Euphorbiaceae (n = 25 spp.), Malvaceae (n = 25 spp.), Rubiaceae (n = 20 spp.), Apocynaceae (n = 18 spp.), and Zingiberaceae (n = 19 spp.).

In terms of IUCN Red List conservation status, at least 65% (n = 520 spp.) were considered to lack formal assessment (62% Not Evaluated, 3% Data Deficient), 32% (n = 262 spp.) were classified under non-threatened categories (30% Least Concern, 2% Near threatened), 3% (n = 22 spp. based on IUCN) fell within threatened categories (2% Vulnerable, 1% Endangered), with an additional 20 species categorised as ‘threatened’ based on DENR-DAO 2019-11.

The distribution of the conservation status categories varied significantly by plant family (χ2 = 862.61, df = 795, p = 0.048). The highest proportion of threatened species was noted among the families Combretaceae (33%) and Nepenthaceae (33%), followed by Myrtaceae (17%) and Meliaceae (14%). Of the 816 documented species, 5% were considered geopolitically endemic to the Philippines. Moreover, the distribution of endemism was significantly related to plant families (χ2 = 236.84, df = 159, p < 0.001). The highest proportion of endemism was observed in the families Dipterocarpaceae (100%), Chrysobalanaceae (100%), Burseraceae (67%), Nepenthaceae (67%), Clusiaceae (50%), Actinidiaceae (50%), Dilleniaceae (50%), Pandanaceae (40%), and Lecythidaceae (33.33%).

3.3 Plant Use Among Ethnolinguistic Groups

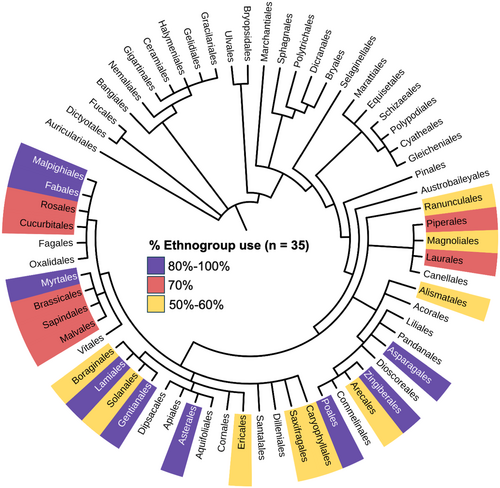

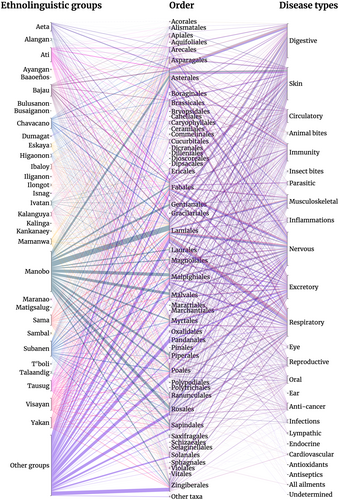

There was an apparent diversity in the distribution of plant species used by ethnolinguistic groups for the treatment of various diseases. In terms of plant use among ethnolinguistic groups, nine out of 68 dominant plant orders (Asterales, Lamiales, Poales, Zingiberales, Asparagales, Malpighiales, Myrtales, Fabales, and Gentianales) were utilised by 80%–100% of the identified ethnolinguistic groups. Eight orders were used by 70% of the groups, and nine were used by 50%–60% (Figure 2). Moreover, a significant relationship was observed between plant use at the family level and the ethnolinguistic group (χ2 = 24095.422, df = 5406, p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Furthermore, we identified 122 plant species used by at least ten ethnolinguistic groups. The Subanen Indigenous People used the greatest number of plants, with 232 species of medicinal plants (30% of all species), followed by the Visayan group (n = 192 spp., 24%) and the Bajau group (n = 190 spp., 23.87%). Moreover, a significant relationship was found between the distribution of plant families and disease applications (χ2 = 20446.937, df = 3816, p < 0.001). Among the identified plant species, 43% were used for digestive diseases and symptoms, followed by skin diseases (n = 342 spp., 42%), nervous system-related diseases (n = 311 spp., 39%), and respiratory diseases (n = 276 spp., 35%) (Figure 3). Interestingly, we found the highest similarities in plant use among the Chavacano, Sama, Tausug, and Yakan groups, all of which are located in the southern Philippines. Similarly, the Bulusanon and Busaiganon groups, located in the eastern part of the country, exhibited similarities in plant utilisation.

3.4 Indicators of Priority and Ecological Correlates of Plant Use

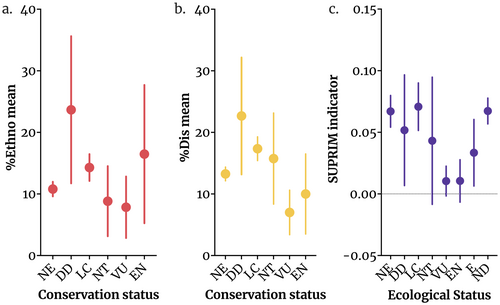

Using the SUPRIM indicator, we compared the priority levels of species based on their taxonomic classification, endemism, and conservation status. We found a strong correlation between %IP and %DIS (Spearman's ρ = 0.757, df = 792, p < 0.001). Although the SUPRIM indicator was higher among species classified as Least Concern (mean = 0.071 ± 0.15) compared to other conservation statuses, we did not find a significant difference in the SUPRIM indicator levels across conservation statuses (Kruskal-Wallis test, H = 9.129, df = 5, p = 0.104) (Figure 4). Similarly, no significant difference was found in SUPRIM levels in relation to species endemism or taxonomic classification at the plant order level.

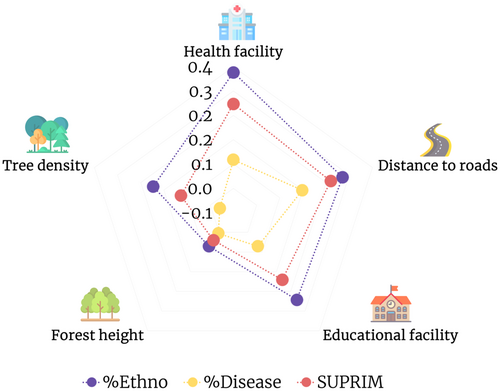

Moreover, we identified a noteworthy correlation between socioecological factors and priority indicators. Factors such as the presence of health facilities, proximity to roads, availability of educational facilities, and tree density were significantly positively associated with the SUPRIM indicators (Figure 5).

4 Discussion

4.1 Research Efforts Towards Traditional Medicinal Plants

Traditional medicinal plants hold significant value in the cultural heritage and knowledge systems of ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, which are deeply embedded and passed down from generation to generation. Studies on traditional medicinal plants across the country began before 2000 and are primarily documented in textbooks or technical reports (see https://www.tkdl.ph/library). However, the publication of field data studies in the form of scientific articles only began in 2010. Our study showed a clear gap in the distribution of studies across the major island groups over time. Although traditional medicine has been widely practiced for centuries in the Philippines, the recent emergence of studies on traditional medicinal plants has marked a significant shift in the perception and research on these plants (Dapar and Alejandro 2020; Pucot and Demayo 2021b). This growing interest may also stem from the increasing recognition of the potential health benefits (e.g., pharmaceutical advancements) offered by traditional remedies (Clemen-Pascual et al. 2022), as well as a deeper understanding of the cultural and historical significance of these plants (Pucot and Demayo 2021b).

The recent surge in the publications of field studies on traditional medicine could be due to a lack of funding or institutional support before 2010. Another possible reason could be a prevailing bias towards Western medicine, which may have overshadowed the potential of traditional remedies in the eyes of researchers and policymakers for the mainstream public (Ekor 2014a; Chali et al. 2021). Furthermore, bias in the distribution of studies across major island groups underscores broader issues of equity and access within the research landscape (Agduma et al. 2023; Hilario-Husain et al. 2024). This further suggests that certain regions or communities may have been marginalised or overlooked in terms of geographical access, socioeconomic disparities, or lack of infrastructure for research and development (Hilario-Husain et al. 2024).

The uneven distribution of studies also raises concerns regarding potential implications for healthcare outcomes and public health policies. Limited research in the country, alongside the government's recognition of public data regarding traditional herbal therapy (Pucot and Demayo 2021a), may contribute to the underrepresentation of traditional medicinal plants in scientific literature. This could mean that important knowledge about effective remedies is being overlooked, leading to disparities in healthcare access and outcomes across different communities. To date, the Traditional and Alternative Medicine Act of 1997, Sampung Halamang Gamot of the Department of Health 1990, and the National Integrated Research Program of the Philippines are the only known initiatives to promote the use of medicinal plants (Maramba-Lazarte 2020). Addressing these disparities will require a coordinated effort from researchers, policymakers, and funding agencies to ensure that research on traditional medicinal plants is conducted equitably and inclusively, resulting in publicly available data. This may involve targeted funding initiatives, capacity-building programmes in underserved regions, and partnerships with local communities to ensure that their knowledge and expertise are valued and incorporated into research efforts. The increased availability of studies on traditional medicinal plants since 2010 represents a positive step towards harnessing the potential of these natural healthcare remedies (Howes et al. 2020). However, it also highlights the need for greater attention to equity and inclusivity in research practices to ensure that all communities benefit from the wealth of knowledge offered by traditional medicine (Badke 2012; Howes et al. 2020).

4.2 Plants and People in the Philippines

Our study found that ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines generally rely on traditional medicinal plants due to their accessibility and availability within their communities. We found a strong similarity among geographically related ethnolinguistic groups, such as Chavacano, Sama, Tausug, and Yakan in the southern Philippines and Bulusanon and Busaiganon in the eastern part of the country. The degree of overlap between neighbouring ethnolinguistic communities suggests extensive traditional knowledge transfer between cultures, as well as the ongoing transmission of this knowledge to future generations (Yurur 2023). The parallels in medicinal plant use among groups with close geographical and linguistic ties indicate that cultural customs and environmental factors have likely shaped and influenced this usage (Saslis-Lagoudakis 2014; Teixidor-Toneu et al. 2018). Geographically close groups or those with linguistic similarities are more likely to interact and exchange knowledge, including information about the use of medicinal plants, resulting in shared practices despite being separate cultural entities. Moreover, historical migration patterns and contact between neighbouring groups may have contributed to the sharing of medicinal plant knowledge as people exchanged goods and cultural practices, including traditional remedies.

In regions where access to modern healthcare is limited, medicinal plants serve as accessible and affordable alternatives, reflecting the resourcefulness of these communities (Badke 2012; de Boer and Cotingting 2014; Howes et al. 2020). The rich biodiversity of the Philippines provides a vast array of medicinal plants, with each ethnolinguistic group utilising plants endemic to their local environment (Carag and Buot 2017; Dapar and Alejandro 2020; Pucot and Demayo 2021b). Beyond mere physical healing, traditional practices often involve holistic approaches that address the spiritual and cultural dimensions of health, emphasising harmony and balance within individuals and communities (Rubio and Naive 2018; Agapin 2020; Berondo 2023). Furthermore, the continued use of medicinal plants serves as a means of preserving indigenous knowledge amidst the pressures of modernisation and globalisation (Fernández-Llamazares et al. 2021; Harisha et al. 2023).

Our study also found that ethnolinguistic groups tended to collect and use plants in areas with high tree and forest cover. Indigenous Peoples often possess an intimate understanding of their local ecosystems and the plants within them, knowledge that has been passed down through generations (Turner et al. 2022). Our findings emphasise the critical relationship between Indigenous communities and their environments, which may play an important role in sustainable resource management, ensuring the availability of medicinal plants for future generations (Hill et al. 2020). This also highlights the importance of protecting forests and indigenous lands for environmental conservation, as well as safeguarding the cultural heritage and traditional knowledge of these communities (Tran et al. 2020; Dawson et al. 2021). Prioritising areas with high concentrations of indigenous plant use is a useful proxy for conservation efforts (Velazco 2022). Medicinal plants represent more than just therapeutic remedies; they also embody cultural resilience, accessible healthcare, biodiversity conservation, and the preservation of traditional wisdom among the diverse populations of the Philippines (Cámara-Leret and Bascompte 2021).

4.3 Priorities for Conservation

Analysis of the SUPRIM indicator offers valuable insights into the prioritisation of species based on taxonomic classifications, endemism, conservation status, and socioecological factors. A strong correlation was observed between the %Ethno and %Dis components of the SUPRIM indicator, indicating that species perceived as important tend to be more distinct within their taxonomic groups and geographical ranges. While the SUPRIM indicator was higher among species categorised as least threatened, no significant difference was detected in SUPRIM indicator levels across different conservation status categories. This suggests that species with varying conservation statuses are perceived with similar levels of importance and distinctiveness by ethnolinguistic groups, emphasising the cultural significance placed on these plants regardless of their conservation status. Similarly, no significant difference was found in SUPRIM indicator levels concerning endemism, implying that both endemic and non-endemic species are equally valued and prioritised for medicinal use by these communities.

Endemic medicinal plant species play a significant role in the cultural heritage and traditional knowledge systems of Indigenous communities. Their loss would not only impact biodiversity but also erode centuries-old healing traditions and cultural identities. Recognising the cultural significance of endemic plants and integrating traditional knowledge into conservation initiatives can help preserve both biodiversity and cultural heritage. Additionally, the presence of threatened and endemic medicinal plants has important implications for biodiversity conservation and traditional healthcare practices in the Philippines. The utilisation of threatened medicinal plants in traditional healing practices raises concerns about unsustainable harvesting practices, which could further endanger these species (da Silva et al. 2019; Campos and Albuquerque 2021). Implementing sustainable harvesting guidelines and regulations in collaboration with local communities and traditional healers is crucial to ensuring the long-term viability of medicinal plant populations (Rajasekharan and Wani 2020). This may involve establishing quotas, seasonal harvesting restrictions, and promoting alternative sources or substitutes for endangered species (Shafi 2021).

Many Indigenous communities in the Philippines rely heavily on traditional medicine for healthcare because of the limited access to modern healthcare facilities. The loss of threatened medicinal plants could deprive these communities of essential healthcare resources, exacerbate health disparities, and compromise the well-being of marginalised populations. Efforts to conserve threatened species should consider the implications for healthcare accessibility and explore alternative sources or substitutes for endangered medicinal plants (Howes et al. 2020; Cámara-Leret and Bascompte 2021; Shafi 2021). Moreover, prioritising endemic and threatened medicinal plants should be a key agenda, as they hold value for their ecological roles, medicinal properties, and conservation needs, contributing to both biodiversity conservation and healthcare innovation (Mir 2021).

4.4 Ecological Predictors of Plant Use

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first extensive synthesis of ethnomedicinal knowledge among ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, with the aim of understanding the socioecological predictors of traditional plant use. The positive relationship between socioecological factors and the SUPRIM indicator highlights the complex interplay between environmental context, healthcare accessibility, and the prioritisation of medicinal plant species among ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines. The correlation between the SUPRIM indicator and factors such as health and educational facilities suggests that ethnolinguistic groups may rely on traditional medicine practices because of their limited access to modern healthcare services (Ssenku et al. 2022; Liheluka et al. 2023). In areas with few and distant healthcare facilities, communities in remote or underserved locations may primarily rely on medicinal plants (da Silva et al. 2019; Howes et al. 2020). The proximity to roads may also influence the availability and accessibility of medicinal plants (Papageorgiou et al. 2020). Communities located farther from major roads may have limited access to markets where modern pharmaceuticals are available, further reinforcing their reliance on locally available medicinal plants (Marrone 2007; Davy et al. 2016). The correlation with educational facilities suggests that the level of education within communities may influence awareness and utilisation of medicinal plants among ethnolinguistic groups. Higher levels of education may lead to greater awareness of modern healthcare practices and Western pharmaceuticals, potentially reducing reliance on traditional medicine (Rahayu et al. 2020; Zubaidah 2020). Conversely, communities with limited access to formal education may have stronger ties to traditional healing practices and medicinal plant usage (Zubaidah 2020; Rondilla et al. 2021; Liheluka et al. 2023). The relationship between socioecological factors and the prioritisation of medicinal plant species emphasises the close ties between the environment, healthcare accessibility, and cultural practices (da Silva et al. 2019; Sousa et al. 2022). Understanding these dynamics is crucial for preserving generations of indigenous knowledge (Tamene et al. 2024) and, most importantly, for designing effective conservation strategies, promoting sustainable healthcare practices, and addressing health disparities in the Philippines.

4.5 Challenges and Progress in Philippine Herbal Drug Discovery

Similar to other nations, the Philippines has adopted different approaches to utilise, preserve, and incorporate traditional medicine into modern medicine. Systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in China, Ayurveda in India, Kampo in Japan, Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM) in Korea, and Unani (Perso-Arabic traditional medicine) are examples of such regulated traditional medicinal practices worldwide (Ansari 2021). In the Philippines, the Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care (PITAHC) was established to improve the quality and delivery of healthcare services to Filipinos by integrating traditional and alternative healthcare into the national healthcare delivery system (Dapar and Alejandro 2020).

Regulatory measures and pharmacovigilance are essential to guarantee the safety and efficacy of herbal medicines (Ekor 2014b). The successful integration of herbal medicines into mainstream clinical practice requires rigorous research, both nonclinical and clinical, comparable to the standards applied to synthetic medicines (Maramba-Lazarte 2020). However, evidence-based herbal drug development faces challenges related to product quality, safety, standardisation, and methodological issues. Nevertheless, there has been increasing adoption of modern pharmaceutical science and ethical standards in this field (Karbwang et al. 2019). This progress has led to the discovery of new and promising therapeutic agents isolated from plants, some of which have since been approved for use (Li and Weng 2017). Notable examples include morphine from Papaver somniferum (Brook et al. 2017) for pain relief, paclitaxel from Taxus brevifolia (Wani et al. 1971) for cancer treatment, vinblastine and vincristine from Catharanthus roseus (Neuss et al. 1959) as cancer therapeutics, and artemisinin from Artemisia annua for malaria treatment (Tu 2011). However, only three of the ten medicinal plants endorsed by the Department of Health of the Philippines in 1997 through R.A. 8423, otherwise known as the Traditional and Alternative Medicine Act, have gained widespread popularity—Vitex negundo, Momordica charantia, and Blumea balsamifera. This is largely due to the limited scientific evidence demonstrating the efficacy and safety of the remaining species of medicinal plants in the Philippines (Tupas and Gido 2021). To discover more local biodiversity with medicinal potential, the Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Health Research and Development (DOST-PCHRD) launched its ‘Tuklas Lunas’ Research and Development Program. This programme aims to develop efficacious, safe, and affordable medicines using standardised methods (Tupas and Gido 2021; DOST-PCHRD 2022).

4.6 Caveats and Moving Forward

Indigenous Peoples are stewards of nature, deeply connected to it through their customs and practices. They play an important role in conserving biodiversity, preserving the environment, and promoting sustainable ecosystem services (Abas et al. 2022). Across generations, they have accumulated a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) (Abas et al. 2022), offering complex insights into local ecosystems, species behaviours, and sustainable resource management strategies (Tanalgo 2017; Sangha et al. 2018; Das et al. 2022). Their management practices, guided by the principles of reciprocity and respect for the natural world, have significantly contributed to biodiversity conservation (Posey 1999; Díaz 2019; Von Der Porten et al. 2019). Indigenous communities are increasingly taking leadership positions in conservation initiatives by combining their traditional knowledge with contemporary scientific techniques (Becker and Ghimire 2003; Rist and Dahdouh-Guebas 2006). The advocacy for land rights and sustainable development models by Indigenous Peoples further underscores their crucial role in conservation (Etchart 2017; Paing et al. 2022). By acknowledging and supporting indigenous contributions, we not only safeguard biodiversity but also promote fairness and sustainability for present and future generations.

Recognising the importance of traditional knowledge for conservation, we developed a database and analysed the traditional use of plants by ethnolinguistic groups. To date, this is the first attempt to synthesise ethnobiological knowledge of traditional Philippine plants and to identify key predictors of their use by ethnolinguistic groups. While our study only covered approximately 30% of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines, it provides a useful overview of the importance of the human-environment relationship and the ecosystem services provided to Indigenous Peoples. We highlight that despite modernisation and rapid development in the Philippines, the value and use of medicinal plant species among ethnolinguistic communities remain intact and continue to be shaped by the environment. While urbanisation and improved access to formal healthcare have introduced alternative and fast medical options, many communities still rely on traditional plant-based remedies, particularly in rural and ecologically diverse regions. In addition to environmental exploitation and rapid environmental changes that threaten traditional knowledge systems by depleting plant populations and altering ecosystems, the rising global demand for herbal medicines places key regions at risk of large-scale, unsustainable harvesting for trade and industry. This underscores the urgent need for effective indigenous-centric conservation approaches that integrate ecological sustainability with cultural preservation to safeguard valuable ecosystem services.

While our research aims to map significant traditional medicinal plants, the communities that rely on them, and their ecological drivers, we acknowledge the potential risks associated with such studies. Specifically, we argue that medicinal plant research and documentation may inadvertently expose Indigenous communities to unethical industrial exploitation and biopiracy (Imran et al. 2021). Therefore, it is essential to adhere to strict ethical guidelines that prioritise the rights, autonomy, and well-being of these communities at every stage of medicinal plant research involving Indigenous Peoples (Celidwen et al. 2023; Plang et al. 2024). The challenges associated with the extraction and use of medicinal plants are linked to their geographical distribution and accessibility. Preserving forest cover and maintaining the remoteness of areas in which these important and threatened species occur are crucial strategies for preventing overexploitation and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Furthermore, we acknowledge that there are important caveats in our present study that need to be addressed, and future analyses present an opportunity to better map and protect indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants. Specifically, improving the robustness of the database by including other ethnolinguistic groups and plant species is a key area for development. To achieve this, we encourage increased funding to support ethnobotanists and conservation biologists in their fieldwork and research, which would help improve current databases and medicinal plant directories (Plang et al. 2024). Investigating the impacts of climate change and continuous land-use changes on important herbal medicines should also be a priority in future studies.

Lastly, we demonstrate the importance of democratising biodiversity data to understand human-environment interactions, especially in fast-changing environments. We hope that our study will inspire greater efforts to document traditional knowledge on plant-use to consequently bolster the protection and conservation of traditional medicinal knowledge and culture in the Philippines and beyond.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the development of this database under the Eco/Con Lab Biodiversity Synthesis+ Centre. Krizler C. Tanalgo: conceptualisation, supervision, methodology, software, formal data analysis, writing the original manuscript, reviewing the manuscript, software, validation, visualisation, and data curation. Yalaira Plang: conceptualisation, formal data analysis, reviewing and editing the manuscript, validation, data curation. Kier C. Dela Cruz: conceptualisation, supervision, methodology, software, formal data analysis, writing the original manuscript, reviewing manuscript, validation, visualisation, data curation. Jeaneth Magelen V. Respicio: data curation, validation, visualisation, reviewing and editing the manuscript. Asraf K. Lidasan: data curation, validation, visualisation, reviewing and editing the manuscript. Sumaira S. Abdullah: data curation, validation, visualisation, reviewing and editing the manuscript. Gerald Vince N. Fabrero: data curation, validation, visualisation, reviewing and editing the manuscript. Angelo R. Agduma: formal data analysis, writing the original manuscript, reviewing and editing the manuscript, validation, visualisation, data curation. Meriam M. Rubio: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Bona Abigail Hilario-Husain: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Renee Jane A. Ele: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Sedra A. Murray: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Lothy F. Casim: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Jamaica Delos Reyes: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Yvonne V. Saliling: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. Radji A. Macatabon: supervision, reviewing, and editing manuscript. All authors approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of our work. We also extend our appreciation to the researchers, practitioners, and community members who have contributed to the documentation of Philippine traditional medicine. Their dedication has provided a crucial foundation for understanding indigenous healing practices and preserving valuable ethnobotanical knowledge. We sincerely thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript. The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available in https://doi.org/10.15468/hj76g7.