What's the story of the elephant? Evaluation of choose-your-own-adventure activities on public perception of human–elephant conflict

与亚洲象的故事?关于人象冲突公众观感的CYOA的评估

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enChoose-your-own-adventure (CYOA) narratives offer immersive experiences that can effectively convey complex conservation concepts, fostering empathy and critical thinking, particularly in addressing issues like human–elephant conflict. Despite their potential, there is limited research on the use of CYOA activities in conservation education. In this study, we created an interactive story centered on elephant conservation, drawing from existing research to distill scientific concepts into engaging narratives and utilizing various modes of delivery (YouTube and live performances) to reach diverse audiences. We conducted postactivity surveys to assess variations in audience perception, learning, and conservation engagement intentions in relation to sociodemographic factors, activity type, and messages encountered. We then modeled the relationships between ordinal responses and explanatory variables using cumulative ordinal mixed models (N = 398). For the YouTube version, we also considered sociodemographic factors (YouTube n = 53, non-YouTube n = 47). Our findings indicate a preference for live performances over online YouTube activity, with participants gaining knowledge about elephant conservation from both formats. For the YouTube activity, participants strongly agreed that the activity allowed engagement with the character and topic. They also expressed a higher likelihood of participating in several conservation actions, relative to a control group. While CYOA storytelling shows promise for conservation education, challenges remain in simplifying scientific language, assessing its impact on comprehension of complex issues, standardizing outcomes, and effectively communicating knowledge. Further research is recommended to adapt this approach, making it applicable to various audiences and domains beyond conservation.

Abstract

zh“CYOA(choose-your-own-adventure,选择你自己的冒险)”的叙事方式能够提供身临其境的体验,可以有效传达复杂的动物保护概念,同时培养同理心和批判性思维,处理人象冲突等问题。然而,关于CYOA在动物保护教育中的应用研究很少。本研究创建了一个涉及亚洲象保护的互动故事,从现有的研究中提炼出科学概念,并将其转化为引人入胜的叙事,同时利用多种呈现方式(例如YouTube和现场表演)来吸引不同的受众。我们进行了活动后调查,以此对和社会人口因素有关的观众观感、学习以及参与动物保护的意图的变化,以及他们接触的活动类型和消息进行了评估。之后,我们使用累积序数混合模型(N = 398)对序数反应和解释变量之间的关系进行了建模。我们还在YouTube版本中考虑了社会人口因素(YouTube n = 53,非YouTube n 47)。总体而言,我们发现现场表演的方式比在线YouTube活动的方式更受欢迎。此外,参与者还从这两种活动中了解了关于亚洲象保护的事情。在 Youlube活动中,参与者非常认同该活动能够让他们参与到人物和主题中。与对照组相比,他们展现出了更多参与多项保护行动的积极性。CYOA叙事方式具有动物保护教育的潜力,但在简化科学语言、评估其对复杂问题理解的影响、结果规范化和有效的知识交流方面仍存在问题。建议通过进一步研究来让这种方法能够适应动物保护以外的不同受众和领域。

Plain language summary

enChoose-your-own-adventure (CYOA) narratives offer immersive experiences that can effectively convey complex conservation concepts, like human–elephant conflict, while also fostering empathy and critical thinking. However, there has been little research on the use of CYOA activities in conservation education. This study created an interactive story based on elephant conservation, drawing from existing research to translate scientific concepts into accessible and engaging narratives, and utilizing various modes of delivery (YouTube and live performances) to reach diverse audiences. We used surveys to assess how participants engaged with the activities, what they learned, and their conservation intentions after exposure. We further analyzed differences in responses based on mode of delivery, message type, and sociodemographic factors. For one of the live performances (Merdeka), we specifically assessed knowledge before and after the activity. The live performances were generally rated more favorably than the online activity, and participants showed an increased understanding of elephant conservation. The Merdeka activity, in particular, led to improvement in knowledge accuracy. CYOA storytelling holds promise for conservation education, but challenges remain in simplifying the scientific language used, assessing its impact on the comprehension of complex issues, standardizing outcomes, and effectively communicating knowledge. Further research is needed to adapt this approach to different audiences and domains beyond conservation.

简明语言摘要

zhCYOA的叙事方式能够提供身临其境的体验,可以有效地将复杂的动物保护概念传达出来,同时培养同理心和批判性思维,处理人象冲突等问题。然而,关于CYOA在保护教育中的应用研究很少。本研究需要创建一个互动故事,内容涉及亚洲象保护,从现有的研究中提炼出科学概念,将其转化为引人入胜的叙事,同时利用多种呈现方式(例如YouTube和现场表演)来吸引不同的受众。我们调查评估了观众在接触活动后的参与度、学习和行为意图,通过进一步分析了解了不同的呈现方式、消息类型和社会人口因素之间的差异。我们对其中的一场现场表演(Merdeka)前后的学习情况进行了评估。现场表演的评分高于在线活动的评分。此外,参与者还了解了关于亚洲象保护的内容,在Merdeka活动之后,参与者知识的准确性有所提高。CYOA叙事方式具有动物保护教育的潜力,但在简化科学语言、评估其对复杂问题理解的影响、结果规范化和有效的知识交流方面仍存在问题。建议通过进一步研究来让这种方法能够适应动物保护以外的不同受众和领域。

Practitioner points

en

-

Choose-Your-Own-Adventure narratives can effectively convey complex conservation concepts, fostering empathy and critical thinking to address issues like human–elephant conflict.

-

Employing multiple delivery methods, such as live performances and online platforms, enables educators to reach diverse audiences and maximize the impact of conservation education.

-

Conducting evaluations and adapting content based on audience feedback can help to simplify scientific language, standardize educational outcomes, and improve communication strategies for better comprehension and engagement.

实践者要点

zh

-

CYOA可以有效地将复杂的保护概念传达出来,同时培养同理心和批判性思维,处理人象冲突等问题。

-

多种呈现方式,如现场表演和YouTube等在线平台,以此能够接触到不同的受众,并最大限度地发挥动物保护教育的影响。

-

根据受众反馈进行评估并调整内容,此简化科学语言,规范教育成果,并改进沟通策略,以获得更好的理解和参与。

1 INTRODUCTION

Stories have a profound and lasting impact on audiences by engaging their cognitive processes, including thought, perception, and imagination (Stein, 1982; Young & Monroe, 1996). Conservation and sustainability are multidimensional fields that encompass social, experimental, and practical aspects (Martín-Regalado et al., 2022; Mbaru et al., 2021). The outcomes of conservation efforts are often long-term and not immediately observable, making them difficult to interpret or experience directly (Margules & Pressey, 2000). Narrative techniques can be highly effective in educating people about complex conservation issues. To strengthen the awareness, attitudes, and motivation for conservation actions, stories can be used in educational settings as a proxy for direct experiences, albeit on a smaller scale, increasing familiarity with the subject matter (Evans & Evans, 1989; Young & Monroe, 1996). Although recreating direct experiences for complex issues is challenging, stories and narratives help bridge the gap between behavior change and the resulting environmental impact (Fazio & Zanna, 1981). Stories increase audience engagement of all ages by encouraging cognitive processing that aligns with existing mental and social frameworks (Bruner, 1986; Young & Monroe, 1996). By personalizing content and immersing the audience, stories capture attention and encourage the proposal of unique solutions (Lepper & Malone, 1987; Young & Monroe, 1996). The use of engaging narratives in education has been shown to positively influence conservation action.

Narrative stories link characters' actions to the plot, effectively reinforcing the consequences of those actions (Frazier & Gonzales, 2022). This narrative structure can incorporate a variety of actions and subsequent outcomes to allow the audience to explore different perspectives within the story, reflecting the diverse motivations and goals of the characters (Dincelli & Chengalur-Smith, 2020). Such simulations provide a safe space for audiences to explore different angles of a problem without being subjected to the negative impacts that may be associated with direct experience. The use of narratives in conservation education has yet to be studied extensively, but some notable positive outcomes have already been found (Din, 2006; Tan et al., 2018).

Meaningful and engaging stories enhance the exploration of complex subject matter and can be incorporated into higher education (Aarseth, 2012; Breien & Wasson, 2021; Bruner, 1986; Ebner & Holzinger, 2007). Engaging narratives typically include elements such as interestingness, coherence, problem resolution, character, concreteness, and vivid imagery (Bruner, 1986; Young & Monroe, 1996). By combining engaging themes, believable characters, and causal storylines, conservation education can achieve its educational outcomes (Breien & Wasson, 2021; Jose & Brewer, 1984).

Choose-your-own-adventure (CYOA) stories offer a dynamic learning experience by presenting different outcomes based on the audience's decisions at various stages of the narrative (Bodrow et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2021). This interactive approach allows participants to engage with content on a more manageable scale (Hanus & Fox, 2015), resulting in long-term learning outcomes that are applicable in real-world settings. The replayability of CYOA stories is a significant advantage, as it allows players to explore different characters and paths, thereby encountering a range of problems and consequences resulting from certain actions (Göbel & Mehm, 2013).

The rationale for developing and exploring CYOA methodology in education is multifaceted. First, it aims to broaden the reach of educational content by making learning more interactive and engaging, which is particularly beneficial for addressing the inefficiencies of traditional, passive learning methods (Panjaitan, 2016). Second, CYOA stories can cater to diverse learning preferences and foster sustained interest by allowing participants to take an active role in their learning journey (Panjaitan, 2016). Third, this methodology is driven by the need for fundamental research in education to explore innovative teaching tools that enhance knowledge retention, critical thinking, and behavioral change. By incorporating elements of choice and consequence, CYOA stories offer a unique way to simulate real-life decision-making processes, making them highly relevant for conservation education (Green & Jenkins, 2014; Jenkins, 2014; Scott et al., 2021).

The plotline of our CYOA narrative designed in this study revolves around the critical issue of elephant conservation. The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) is one of the three extant elephant species globally (Sharma et al., 2018). Today, this species faces significant threats from habitat destruction and fragmentation, driven by the rising development of agricultural activities. As humans and elephants increasingly share the same landscapes, conflicts have become more frequent (Billah et al., 2021; Ladue, Eranda, et al., 2021). Human–elephant conflict (HEC) in Malaysia dates back to the early 1900s but has intensified since the 1950s with the advent of large-scale plantations, leading to an annual increase in conflict incidents from 8% to 22% (Wahab et al., 2016). HEC can result in injuries or fatalities for humans and elephants, economic losses, and psychological distress. Specifically, annual crop loss due to elephant conflict, affecting crops such as oil palm, rubber, durian, and banana for 137 respondents, was reported to cost RM 2,962,475 over an area of 4638 hectares, including expenses for seedlings, labor, fertilizer, and pesticides (Sinha, 2022). The economic and psychological toll of these conflicts has been cited as justification for translocating elephants from conflict areas, though the effectiveness of this strategy in reducing HEC has been mixed (Fernando & Pastorini, 2011; Ly, 2011; Saaban, n.d.). Moreover, conflicts have led to retaliation by affected stakeholders through poisoning, poaching, and shooting (LaDue, Eranda, et al., 2021). LaDue, Farinelli, et al. (2021) reported a positive correlation between farming yields and elephant deaths, with 70% of these deaths attributed to humans. The population of Asian elephants in Peninsular Malaysia has significantly declined in part due to this conflict, with estimates suggesting only 1223–1677 individuals remain in fragmented habitats (IUCN, 2023).

Given the critical status of Asian elephants and the escalating HECs, there is an urgent need for comprehensive education and awareness programs to foster coexistence. HECs are generally tackled through a combination of short- and long-term strategies, integrating education and land-use planning (Sampson et al., 2021). Here, we developed a story featuring a male elephant as the main character, allowing players to choose the elephant's actions, leading to different outcomes. The objective of this narrative was to educate players about the threats faced by Asian elephants through anthropogenic causes (e.g., land use conversions, poaching) and to explore ways to protect these elephants. The use of CYOA stories, with the elephant as the protagonist, aims to instill empathy through self-identification, potentially bridging the gap in conservation education and mitigation planning. Moreover, CYOA narratives enable the audience to engage in critical thinking and explore counterfactuals, carefully considering alternative strategies for mitigating HECs and understanding the direct consequences of their decisions without facing any real-world repercussions. This approach allows players to explore alternate outcomes for the elephants and affected stakeholders, enhancing narrative persuasion and deepening their understanding of conservation challenges (Jenkins, 2014).

CYOA activities have been widely utilized for pedagogical research in various fields, including conservation (Green & Jenkins, 2014; Jenkins, 2014; Scott et al., 2021). However, their application in conservation education remains limited, and their educational effectiveness has yet to be thoroughly assessed (Andrade et al., 2022). Additionally, the relationship between narrative teaching styles and student performance and motivation is not well understood (Chen et al., 2019; Cliburn & Miller, 2008). Therefore, this study aims to create a CYOA story revolving around the theme of elephant conservation, with a focus on understanding its effects on participants' learning, behavior, and perceptions using narratives based on local HECs.

The primary objectives of this study are to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of using interactive CYOA stories as an educational tool to enhance knowledge and shift attitudes toward elephant conservation and HEC among diverse audiences; (2) assess the impact of this educational intervention on participants from different backgrounds, specifically members of the plantation and Lok Heng community who are directly affected by HEC, as well as high school students engaged in STEM education; and (3) explore the potential of CYOA stories to foster a deeper understanding of conservation issues and promote behavioral change.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Story creation and delivery

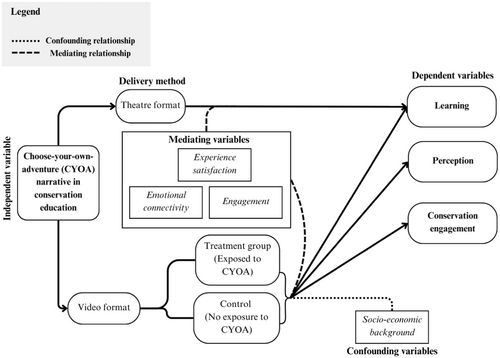

An extensive research and literature review on elephant behavior, the ecological impact of elephants on ecosystems, HEC issues, and conservation strategies was conducted to understand pertinent issues (Appendix SA), which then informed the development of the interactive CYOA story. Complex scientific concepts were simplified into accessible and engaging narratives while ensuring that the material remained scientifically accurate and relevant. This process involved first identifying core ideas, translating technical terms into everyday language, and then synthesizing the topics into a coherent storyline. The resulting story was both understandable and engaging for the public while preserving its educational value. The story was delivered in two modes: online animation via YouTube and live performances. Both formats allowed for participant interaction at fixed decision-making intervals, leading to one of four possible endings, which were framed either positively or negatively. The YouTube version of the story was disseminated through social media platforms from 14 March to 14 August 2022. At the end of the activity, participants could choose to replay the story, and if they did, they were asked in the postactivity survey how many endings they had witnessed. The live performances were conducted at two events with different audiences. The first was at the “World Elephant Day” (WED) carnival in FELDA Lok Heng Barat, Johor, on 13 August 2022, where the story was performed three times (10:00 AM, 1:00 PM, and 3:00 PM) for members of the plantation and Lok Heng community, who frequently face conflicts with elephants due to crop-raiding. The second event was part of the “Merdeka Lecture” series at the University of Nottingham Malaysia (UNM) campus on 1 September 2022, where the story was performed once for high school students to spark their interest in STEM education. During the live performances, a collective decision-making process was implemented through audience voting, with the majority vote determining the story's direction. The stories for the online and live versions differed slightly, with the live performances being extended to increase the duration of audience engagement (Appendices SB and SC). Figure 1 illustrates the research concept, focusing on the evaluation of the CYOA's impact on audience perception, learning, and engagement in conservation activities related to elephant conservation. Table 1 summarizes the parameters measured and the research questions tackled.

| Event | Types of surveys | Covariates measured | Number of participants | Gender | Age | Region of current residence | Socioeconomic level (class) | Occupation | Research questions answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Elephant Day (live) | Postactivity | Number of participants, sociodemographic details not collected | 39 | What is the knowledge, perception and engagement with the complexities of elephant behavior of participants living near elephants and experiencing human–elephant conflict postactivity? | |||||

| Merdeka (live) | Pre- and postactivity | Number of participants, sociodemographic details not collected | 259 | How does high school students' understanding and engagement with the complexities of elephant behavior differ between pre- and postactivity? | |||||

| YouTube (online) | Postactivity | Number of participants, sociodemographic details collected | 53 | Males: 21 | >25 years old: 25 | Southeast Asia: 43 | Nonworking: 5 | Education: 16 | - How effective is the online CYOA story in delivering conservation messages and influencing participants' knowledge, attitudes, and potential conservation behaviors? - What sociodemographic variables might explain the variation in response to the online activity? - How do different message types (positive, negative) and ending types (direct, indirect, multiple) in CYOA stories impact viewers' behavioral intentions toward conservation actions? |

| Females: 32 | <25 years old: 28 | Others: 23 | Working: 15 | Others: 37 | |||||

| Middle: 20 | |||||||||

| Upper middle: 13 | |||||||||

| Control for YouTube | 47 | Males: 9 | >25 years old: 16 | Southeast Asia: 25 | Nonworking: 3 | Education: 23 | |||

| Females: 38 | <25 years old: 31 | Others: 22 | Working: 9 | Others: 24 | |||||

| Middle: 8 | |||||||||

| Upper middle: 27 |

- Note: For the YouTube activity, as of January 31, 2024, the introduction video had 193 views. Some of the views might have come from the same participants. Nevertheless, only 53 viewers responded to the survey.

- Abbreviation: CYOA, choose-your-own-adventure.

To evaluate audience experiences of the CYOA activities, postactivity surveys were designed and administered at the end of each activity. The survey for the YouTube activity gathered participants' opinions on the most effective methods to protect elephants and curb poaching, their understanding of the ecological role of elephants, and their likelihood of engaging in a range of conservation activities. It included sections where respondents rated (on a Likert scale of 1–6) their engagement in specific behaviors, expressed their agreement or disagreement (on a Likert scale of 1–6) with statements related to conservation issues, and reported on actions taken while traveling, as well as their volunteer and donation behaviors (Appendix SD). Additionally, the survey sought feedback on a conservation-themed activity, evaluating participants' intrinsic motivation, overall experience, the most important lesson learned from the activity, and the most important question they had after the activity. The item on the most important lesson learned provided insights into the audience's understanding of the complexities of HEC and the need for sustainable solutions. The item on the most important question captured participants' curiosity and potential areas for further exploration, which could help to identify knowledge gaps for continued learning. The survey also collected sociodemographic details, including Gender, Age, Region, Socioeconomic level, and Occupation, with categories provided in Appendix SD. A QR code linked to the survey was provided at the end of the final YouTube video.

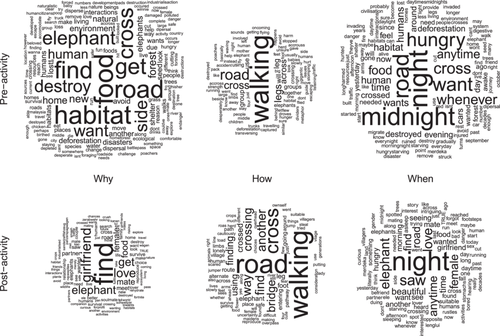

In the live version of the activity, the audience was asked three key questions: “Why, how, and when did the elephant cross the road?” These questions were designed to assess their understanding and engagement with the complexities of elephant behavior. The “why” question explored their interest in the motivations behind the elephant's behavior, “how” gauged their curiosity about the biological mechanisms and challenges involved, and “when” measured their awareness of the importance of timing in human–elephant interactions. Responses were collected both pre- and postactivity for the UNM Merdeka performance, and only postactivity for the Lok Heng Barat performance. Further details on the surveys are presented in Appendix SD.

The postactivity surveys differed between the online and live versions for several reasons. First, the time constraints during live events only permitted a brief survey to be administered after the activity, which also meant that sociodemographic details were not collected. Second, to assess the effectiveness of the online activity in delivering a conservation message, we administered a similar online survey to a control group that had not participated in the activity. This control group was recruited via social media, in the same way as the “online activity” group. Third, the differing audiences for each activity made it challenging to directly compare the responses. Hence, we adjusted the survey for each activity based on the research question we would like to address. The details of the survey designs for the online and live versions are outlined in Appendix SD.

2.2 Statistical analysis

We used a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare the ordinal ratings of the activities against a neutral score (3). We also compared each pair of ratings of the three activities using Mann–Whitney U tests. These nonparametric tests are particularly suitable for analyzing ordinal data. To determine if the lessons learned postactivity differed among the three activities, we first categorized the open-ended responses into three types: knowledge, understanding, and application. A response was categorized as “knowledge” if it involved a fact or information about elephants. If the response provided a reason or mechanism explaining elephant behavior, it was categorized as “understanding.” Responses indicating what the participant intended to do to benefit elephants were classified as “application.” We then used Fisher's exact test to assess whether the types of lessons learned differed across the activities.

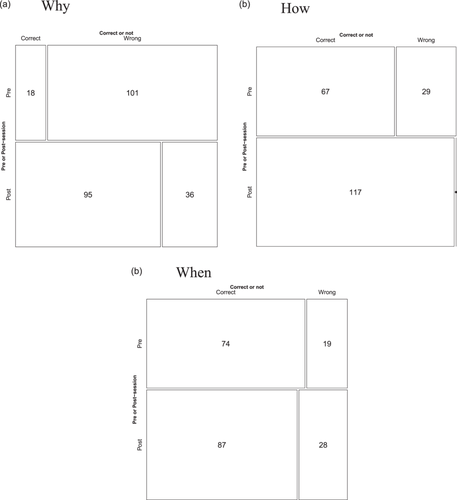

For the live performance at UNM, we first assessed the accuracy of participants' responses to the questions “Why, how, and when did the elephant cross the road?” by marking the correctness of each response. We then used Pearson's chi-squared test to determine whether the accuracy of responses differed between the preactivity and postactivity phases.

It is pertinent to note that the UNM event boasted a notably larger sample size of 259 participants, compared to the 39 participants at the WED event. While both events shared similarities, our focus primarily centered on the UNM event due to its direct relevance to the study objectives and the availability of more comprehensive data. We emphasize this context to provide transparency regarding data exclusion, ensuring clarity and rigor in our reporting of methodologies and results.

To examine whether the responses to the YouTube version differed according to socioeconomic factors, we employed a generalized linear model (GLM). The survey responses (statements 4–8 and 16–18) served as the response variable, with “gender,” “age,” “region,” “socioeconomic level,” and “occupation” as explanatory variables. Given the small number of participants in certain categories, we grouped them as follows: age (below 25 or above 25 years old), region (Southeast Asia [SEA], others), socioeconomic level (nonworking, working, middle, or upper-middle), and occupation (education, others). Additionally, to examine the effects of the activity's message on behavioral intentions, we also applied a GLM, using the responses to each of the 12 “behavioral intention” statements (question 4) as the response variable. The explanatory variables included “gender,” “age,” “region,” “socioeconomic level,” and “occupation,” along with “ending type” and “message type.” The “ending type” was categorized as “direct,” “indirect,” or “multiple.” A “direct” ending relates to the behavioral intention statement in the survey. For example, if the video's final message was “Slow down to save elephants,” it aligns with the survey statement “Be mindful and slow down when driving on roads with animal crossings.” An “indirect” ending refers to an end statement that is unrelated to the behavioral intention statements in the survey. “Multiple” means that the participant was exposed to both “indirect” and “direct” messages because they chose to replay the story. The study categorized “message type” as “positive,” “negative,” or “multiple.” A “positive” message highlights the beneficial, optimistic, or constructive aspects of a situation or idea. For example, one of our endings features a positively framed message: “Slow down, and you can help save elephants and your life.” Conversely, a “negative” message emphasizes the potential loss or adverse consequences, such as: “Slow down, or you may injure elephants and yourself.” When participants were exposed to both types of messages, it was categorized as “multiple.” For analyzing the survey data, different statistical models were employed based on the type of response variable. Binary response variables were analyzed using the “Binomial” error family, numerical (counts) used the “Poisson” error family, and ordinal data were analyzed with a cumulative link model.

3 RESULTS

The study created an interactive CYOA story focusing on elephant conservation, delivered through online animations on YouTube and live performances. Postactivity surveys were conducted to evaluate participants' engagement, understanding, and behavioral intentions. Statistical analyses were then performed to compare responses across different formats and socioeconomic factors. The sample sizes, along with the sociodemographic profiles of the participants, including those from the control group, are summarized in Table 1.

3.1 The efficacy of delivery methods in CYOA activities

To assist in interpreting the results, numbers in brackets are displayed in the following format: estimate of the difference in means ± standard error of the difference, significance of the p-value (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001), test statistics.

The study found that all activities—Merdeka, WED, and YouTube—received significantly higher overall ratings compared to the neutral score of 3 (Table 2). Specifically, theatrical activities were rated higher than the online activity (see Table 2). WED received notably higher ratings than YouTube, while Merdeka's ratings, though higher than YouTube's, were lower than those for WED (Table 2, Figure SE2). Participants across all activities primarily gained insights into elephant conservation, with slight variations in focus: WED emphasized elephant behavior and factors contributing to HEC, Merdeka highlighted coexistence, protection, and conservation, and YouTube concentrated on threats like poaching and habitat fragmentation. Fisher's exact test indicated no significant difference in the lessons learned among the three activities (p > .05) (see Table 2, Figures SE2 and SE3 for details).

| Activity | Overall rating | Pairwise comparison results | Lessons learned (main) | Fisher's exact test for lessons learned | Additional figures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merdeka | Significantly higher than 3 | Higher than YouTube (p < 0.01) | Coexistence, Elephant Protection, Conservation | No significant difference (p > 0.05) | Figures SE1 and SE2b |

| World Elephant Day | Significantly higher than 3 | Higher than YouTube (p < 0.001), Higher than Merdeka (p < 0.05) | Elephant Behavior, Factors contributing to HEC | Figures SE1 and SE2a | |

| YouTube | Significantly higher than 3 | Lower than Merdeka and World Elephant Day | Threats: Poaching, Habitat Fragmentation, Human Responsibility | Figures SE1 and E2c |

- Abbreviation: HEC, human–elephant conflict.

In the Merdeka activity, participants' postactivity responses to the three questions “Why, how, and when did the elephant cross the road?” were more consistent compared to their preactivity responses (Figure 2). The majority of preactivity responses to “why” focused on the motivations of elephants to seek shelter and sustenance, as well as habitat loss, while postactivity responses centered on the elephants' need to forage and for social interaction, particularly to find a mating partner. For “how,” prevalent answers from preactivity were on physical mechanisms used by elephants in road-crossing movement, for example, “crossed,” “walked,” and elephants' social behavior, that is, traveling in social groups. Postactivity responses were similar to the preactivity but included additional mentions of the paths elephants take, such as wildlife crossings, bridges, and overpasses. Responses to “when” revolved around the need to crossroads for food, shelter, or due to habitat loss, and the time that elephants would make these crossings, that is, midnight. The postactivity had similar themes to the preactivity, where participants mentioned the exigencies that result in road-crossing behavior exhibited by elephants, that is, for food and finding a partner, and the time these crossings were made, that is, anytime and night.

The chi-square test output revealed significant differences in the correctness of responses to the questions “why” (χ² = 80.623, df = 1***, Figure 3a) and “how” (χ² = 38.386, df = 1***, Figure 3b) pre- versus postactivity. However, there was no significant difference for the question “when” (χ² = 0.25502, df = 1, Figure 3c).

3.2 Effects of the online activity on learning, behavior, and perception

The online activity was analyzed in greater detail, offering a comprehensive examination of its impact on learning, behavior, and perception. This format allowed for an in-depth survey that gathered both quantitative data on audience engagement and qualitative insights into participants' perceptions and learning outcomes regarding elephant conservation. A control survey was also implemented, providing a basis for comparison (Table 1). The wide range of topics and demographics covered in both surveys provided a detailed understanding of how exposure to a YouTube video on conservation influences audience perception, learning, and engagement.

3.2.1 Perception

Participants' overall perception of the activity was positive, with all statements receiving ratings above average (≤3.5) (Figure SE4; Table S7). On average, participants strongly agreed that the activity allowed engagement with both the character and the topic. This enjoyment was reflected in high ratings for the following statements, that is, “time flew by,” “enthusiastic and excited,” “enjoyment,” and “overall satisfaction level of experience.” Furthermore, the activity helped participants deepen their understanding of conservation and attain positive feelings, as evidenced by the average ratings for statements like “strengthen my understanding of conservation” and “think I can help elephant achieve a good outcome.” Many participants found that their prior understanding of conservation was helpful during the activities. Details on (1) the best and most memorable features, (2) suggested improvements, and (3) participants' feelings are detailed in Figure SE6.

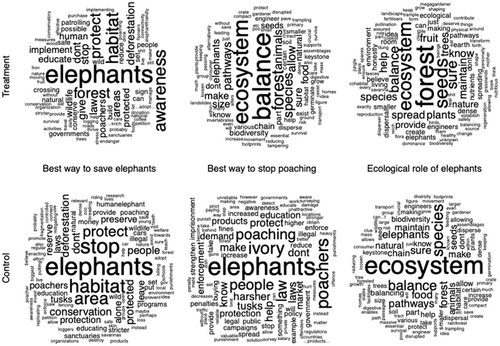

The responses to the three open-ended questions in Figure 4 reveal a wide diversity of answers. Both groups emphasized habitat protection and education as key strategies for saving elephants. However, there were notable distinctions: the treatment group mentioned law enforcement activities and wildlife bridges, while the control group suggested coexistence strategies.

When asked about the best methods to stop poaching, both groups focused on the importance of proper governance, stricter law enforcement, punishments for poachers, and education. The responses from the treatment group were more diverse when discussing the ecological role of elephants, but the themes were consistent. Participants recognized the role of elephants as keystone species, ecological engineers, and seed dispersers, and acknowledged the importance of elephant feces for soil fertility.

3.2.2 Learning

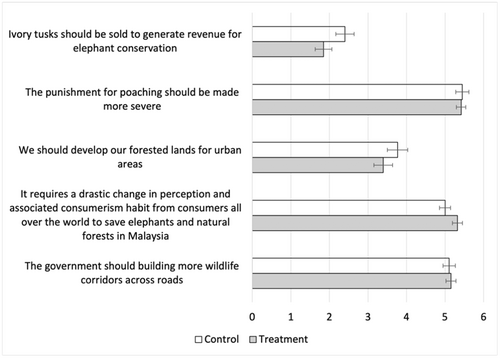

The online survey responses comparing the control and treatment groups showed similar levels of learning across statements on poaching, development, governance, and behavioral change (Figure 5). The responses only differed for one statement (Table S1): selling ivory to generate income for elephant conservation (−1.183 ± S.E. 0.461 ***, LR = 15.750).

Regarding the correctness of eight statements on elephants and forests, the treatment group showed slightly higher average correctness (Treatment: x̄ = 2.811 ± 0.183; Control: x̄ = 2.362 ± 0.198). However, the differences were not statistically significant (0.704 ± 0.409 S.E., LR = 2.984) (Table S2).

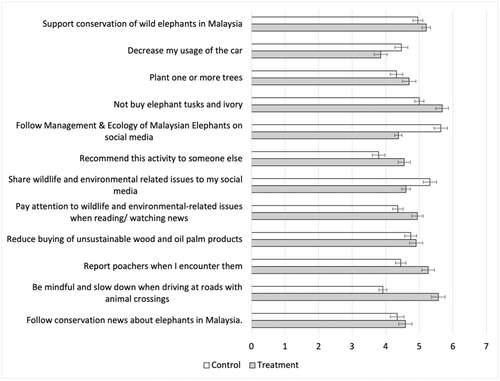

3.2.3 Engagement

Significant differences were observed between the control and treatment groups in their likelihood to engage in conservation activities, as shown in Figure 6. Specifically, the treatment group exhibited a higher likelihood of participating in five key actions: reporting poachers (1.214 ± S.E. 0.429**, LR = 8.257), paying attention to wildlife and environmental issues in the media (0.956 ± S.E. 0.423*, LR = 5.230), sharing wildlife and environmental issues on social media (−1.399 ± S.E. 0.438**, LR = 10.806), recommending the activity to others (1.535 ± S.E. 0.427***, LR = 13.500), and supporting the conservation of wild elephants in Malaysia (0.827 ± S.E. 0.422*, LR = 4.074) (Table S3).

However, participants from the treatment group ranked lower for statements related to actions taken when encountering wildlife on the road (Figures SE5): “Stop when I see an animal crossing the road” (Treatment: x̄ = 2.453 ± 0.190; Control: x̄ = 3.149 ± 0.199), “Slow down when I see ‘animal crossing’ signs” (Treatment: x̄ = 2.585 ± 0.178; Control: x̄ = 2.809 ± 0.154), and “Look out for signs on speed limit and animal crossings” (Treatment: x̄ = 3.000 ± 0.148; Control: x̄ = 3.319 ± 0.258).

Conversely, the treatment group ranked higher for statements regarding the timing of driving (Treatment: x̄ = 3.528 ± 0.204; Control: x̄ = 3.043 ± 0.164) and the use of public transport (Treatment: x̄ = 3.434 ± 0.208; Control: x̄ = 2.681 ± 0.234). Significant differences were found between the control and treatment groups for three statements: taking public transportation (1.067 ± S.E. 0.413*, LR = 6.874), driving during the day instead of at night (0.758 ± S.E. 0.403*, LR = 9.457), and stopping when encountering an animal crossing the road (−1.159 ± S.E. 0.427*, LR = 7.620).

3.3 Factors affecting learning, behavior, and perception in the online activity

3.3.1 Participants' sociodemographic background

Perception

Gender significantly influenced two key perceptions. Participants' excitement and enthusiasm showed a significant gender difference, with males rating lower than females (−1.608 ± S.E. 0.646*). Overall satisfaction also differed by gender, with males again rating lower than females (−3.252 ± S.E. 0.907***). Additionally, age played a role in overall satisfaction, where participants aged above 25 years rated higher than those younger than 25 years (1.549 ± S.E. 0.707*) (Table S7).

Learning

Region of residence was the only sociodemographic factor that influenced participants' agreeability to the need for a global perception and consumerism habit change to save elephants and natural forests in Malaysia. Participants from the Southeast Asian region rated higher on this statement than participants from other regions (1.968 ± S.E. 0.832*) (Table S4).

Engagement

Several variables affected participants' likeliness to engage in conservation actions: Participants aged 25 years and above (−1.194 ± S.E. 0.593*) and in nonconservation related occupations (−1.368 ± S.E. 0.655*) were less likely to follow conservation news about elephants in Malaysia. Male participants (0.615 ± S.E. 0.675**) were more likely than females to report poachers, while those in nonconservation-related occupations were less likely to report poachers than participants engaged in conservation-related occupations (−1.255 ± S.E. 0.741*). Southeast Asian participants were more attentive to wildlife and environmental-related issues in the media (1.490 ± S.E. 0.717*). Participants in nonconservation occupations were less likely to stop purchasing elephant tusks and ivory (−21.177*), although the variation in responses was minimal (most strongly agreed), causing the model not to converge. Therefore, no standard errors were reported in the results (Table S5), and the output should be interpreted cautiously. Participants aged above 25 years old (−1.388 ± S.E. 0.607*) and from a nonconservation occupation (−1.290 ± S.E. 0.646*) were less likely to engage in tree planting. Males scored lower than females on supporting the conservation of wild elephants in Malaysia (−1.322 ± S.E. 0.622*) and on choosing public transport over driving (−0.952 ± S.E. 0.558*).

3.4 Ending and message type on behavior and perception

The ending type in the CYOA activity did not significantly affect participants' responses to statements related to driving mindfully, reporting poachers, recommending the activity, planting trees, decreasing car usage, or supporting wild elephant conservation (Table S6).

Moreover, the difference in message type (positive or negative) did not affect participants' likelihood to engage in future conservation activities, but certain socioeconomic factors did (Table S6): Participants aged above 25 years were less likely to recommend the activity (−1.208 ± S.E. 0.655*) or be involved in tree planting (−1.479 ± S.E. 0.654*); nonconservation jobs had a negative influence on involvement in tree planting (−1.469 ± S.E. 0.678*); and being a Southeast Asian participant had a positive effect on driving mindfully on roads with animal crossings (2.00 ± S.E. 0.981*).

We found that message type affected participants' feelings. Specifically, positive messages were associated with increased positive feelings toward the activity (−1.289 ± S.E. 1.313*), while the opposite was found for negative messages (Table S7). Participants' overall satisfaction was also influenced by the ending type (1.575 ± S.E. 1.209*), with ending types 3 and 4 showing a more positive satisfaction level relative to other endings (Table S7).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 The efficacy of delivery methods in CYOA activities

Previous studies have explored various forms of CYOA activities, including visual novels, texts, and questionnaires. In our study, we tested two distinct delivery modes—live theater performances and online videos—to disseminate messages on elephant conservation. Our findings indicate a difference in participants' overall satisfaction between the two approaches, with live theater (WED and Merdeka performances) receiving higher ratings compared to the YouTube video format. The preference for live theater suggests that physical activities may foster more active participation and higher audience engagement than online activities. This aligns with existing literature that emphasizes the importance of a sense of peer community and engaging instruction in successful online learning environments (Norman, 2020). In contrast, our online activity lacked narration, potentially resulting in lower audience engagement levels. Narration in storytelling can enhance engagement by incorporating vocal elements such as tone, loudness, accents, and emotion, which may increase the attention span of the audience. Given these findings, future studies should explore whether the inclusion of narration in online CYOA activities could improve audience engagement and learning outcomes.

Regardless of the delivery method, participants from both the online and theatrical activities successfully captured the central message of elephant conservation and protection. The WED and Merdeka activities managed to convey themes of HEC and coexistence, while the YouTube activity focused on anthropogenic threats that elephants face and the human responsibility to conserve and protect these sentient beings. The results from the Fisher's exact test confirmed the similarities between the messages received by participants across the three activities, verifying the effectiveness of each delivery method in conveying the story's objectives.

The uniformity of responses in the postactivity surveys, compared to the preactivity surveys, suggests that participants were able to clearly encapsulate the overarching theme of the events. For all questions, participants' responses mirrored our hypotheses. They demonstrated an understanding of (1) the intrinsic reasons behind elephant behavior, (2) the general physical mechanisms involved in elephant movement and social behavior when crossing roads in groups, and (3) the time elephants normally cross the roads and behaviors resulting in road crossings.

These responses were consistent with existing research, such as Wadey et al. (2018), which describes road-crossing behavior in elephants as predominantly nocturnal, and Yamamoto-Ebina et al. (2016), which notes that elephants are often attracted to highways due to food availability. Postactivity responses were generally more accurate than preactivity responses; for instance, participants refined their answers to “when,” answering “midnight” and “night” in the preactivity survey and “night” for postactivity. Some of the postactivity answers were new, with participants noting the utilization of wildlife bridges for road-crossing. Similarly, when asked about the reasoning for elephant movement, participants added “social behavior,” that is, looking for mates, as one of the motivations behind road-crossing.

These patterns suggest that the activity helped correct misconceptions about elephant movement behaviors and deepened participants' understanding of the underlying mechanisms and elements involved. An increase in the number of correct responses was exhibited by participants in the postactivity survey for the “why” and “how” questions but not for “when,” possibly due to participants' awareness of the timing of elephant movement before the activity. These findings are consistent with previous studies by Melcer et al. (2020) and Panjaitan (2016), which showed that participants scored higher on postactivity surveys after being exposed to CYOA stories. CYOA activities provide appropriate contextual frameworks that help learners correct misconceptions and may improve the long-term retention of new knowledge.

4.2 Effectiveness of the online activity for learning, perception, and engagement

The perception of the online activity was positive, with participants expressing general satisfaction with the experience. The activities allowed participants to engage with the characters and topics of the story while also strengthening their understanding of elephant conservation. The concept of “online CYOA” offers an alternative narrative style of teaching, similar to educational video games. The CYOA activity available on YouTube functions much like a point-and-click video game in its mechanics. Research indicates that students are more motivated to learn ecological concepts through video games, with learning performance comparable to traditional methods (Hwang et al., 2013; Kuo, 2007). This suggests that our online CYOA can be an effective tool for enhancing ecological education and engaging learners. Additionally, the positive attribution toward the CYOA activity is consistent with findings from previous studies, with participants finding the CYOA format to be engaging, enabling a deeper understanding of the subject due to its interactive nature (Jenkins, 2014; Panjaitan, 2016; Scott et al., 2021; Stanfill & Martin, 2023; Thomas et al., 2022). Qualitative responses from participants highlighted the flexibility to explore alternative endings, the engaging storyline, animation, and messages as the best features of the activity. By allowing the exploration of multiple endings, the participants were able to understand the cause and effect of different actions. This reiterative method of understanding a new concept also contributes to strengthening learning outcomes.

To confirm the effectiveness of the online activity for individual learning, perception, and engagement in conservation, we measured the differences in audience responses toward different statements between the control and treatment groups.

4.2.1 Perception

Participants' perceptions regarding the best methods to save elephants, prevent poaching, and understand the ecological role of elephants were more diverse in the treatment group compared to the control group. Despite this diversity, there were notable similarities in the themes of responses from the two groups. This suggests that the CYOA activity may have broadened participants' understanding of elephant conservation. According to Scott et al. (2021), CYOA activities allowed pharmaceutical students to explore different treatment options for patients by simulating real-life clinical scenarios, thereby enabling a shift in perception from the “black-and-white” approaches typically seen in conventional learning. This broadening of perception through CYOA activities encourages creative thinking in problem-solving, a skill that is not easily cultivated through traditional teaching methods.

4.2.2 Learning

The responses between the control and treatment groups were largely similar across most statements, except for one concerning the sale of ivory to generate income for elephant conservation. The consistency in responses between the two groups may indicate that participants had a basic understanding of elephant conservation, regardless of their exposure to the activity (Panjaitan, 2016). This suggests that incorporating more advanced ecological content could potentially enhance the learning outcomes for participants. However, the baseline knowledge may differ for species that are less charismatic than elephants, which could result in greater differences between control and treatment groups in such cases. Nonetheless, these findings are valuable for refining the content and delivery of future CYOA educational approaches.

Similarly, although the correctness of responses to statements about elephants and forests did not differ significantly between the control and treatment groups, the latter exhibited a slightly higher correctness level. Scott et al. (2021) corroborated an improvement in learning outcomes of course contents in pharmaceutical students exposed to CYOA activities compared to those who attended conventional lectures.

4.2.3 Engagement in conservation

The CYOA activity showed a notable effect on participants' intentions to engage in future conservation actions. We found that participants from the treatment group were more likely to report poachers, pay attention to wildlife and environmental issues in the media, recommend the activity to others, and support wild elephant conservation in Malaysia. Interestingly, while these participants showed increased engagement in several areas, they were less likely to share wildlife and environmental issues on social media compared to the control group. Moreover, the treatment group assigned higher importance to five statements related to driving on highways known for wildlife crossing, indicating a heightened awareness of the risks involved. Furthermore, only participants' region of residence was found to influence their responses toward the statement on reporting poachers. These findings may allude to the higher awareness of the negative impacts that human activities have on elephants and their conservation. This awareness is key for shifting community attitudes away from fear and uncertainty about elephant presence and toward a deeper understanding of elephant behavior—a crucial step toward human–elephant co-existence.

Although the objective of the study was to explore intentions to engage in conservation as an outcome of the CYOA activities, it did not measure actual behaviors or actions taken concerning these environmental issues, which would provide a more accurate assessment of the effectiveness of this teaching method. Future studies should consider focusing on the retention of learning outcomes and how this, in turn, influences real-world behavioral changes.

4.3 Influence of sociodemography, ending, and message type on perception, learning, and engagement in the online activity

4.3.1 Perception

The study revealed that participants' perceptions of certain aspects of the CYOA activities, that is, overall satisfaction, positive feelings, excitement, and enthusiasm, were influenced by the type of message, story ending, and demographic factors such as gender and age. Participants who were exposed to positively reinforced messages reported more positive feelings toward the activity. The type of ending also played a role, positively influencing overall satisfaction with the activity. Gender and age also influenced satisfaction levels, with males generally reporting lower satisfaction than females, and participants aged 25 years and younger showing higher satisfaction levels. These findings suggest that narrative teaching styles, such as those employed in CYOA activities, have the capacity to change an audience's perception, which is an effective tool for facilitating learning about complex animal behaviors. This approach could be particularly impactful in altering the perceptions of individuals who have experienced negative encounters stemming from HECs.

4.3.2 Learning

Region of residence, that is, SEA, was the only significant factor influencing participants' learning outcomes in this study. Participants from this region were more likely to agree on the need for a global shift in perception and consumer habits to protect elephants and natural forests in Malaysia. This heightened awareness may be linked to participants' familiarity with ongoing wildlife and environmental conservation issues prevalent in developing countries. These issues include deforestation and habitat loss, driven by agricultural expansion to meet international market demands (Chakravarty et al., 2012; Taheripour et al., 2019; Vadrevu et al., 2019).

4.3.3 Engagement

Past studies have reported varying effects of sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental engagement and perception change (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Erdogan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2019). In this study, we found that the intention to engage in conservation was influenced by several factors, including age, occupation, region of current residence, and gender. However, caution is warranted in interpreting these results, as there were inconsistencies in the significance levels of some of our models when ending and message types were added as predictors. Contrary to past studies (Li et al., 2019), participants aged 25 years and below in this study were less likely to engage in conservation actions, that is, following conservation news about elephants and tree-planting activities. This lower level of engagement may be attributed to factors like environmental literacy (Jannah et al., 2013), as formal environmental education in the studied region is limited (Kamaruddin et al., 2019). On the other hand, we found that participants from the SEA region were more likely to pay attention to wildlife and environmental issues in local media. This is consistent with findings from Praet et al. (2023), where participants frequently narrated threats caused by marine litter prevalent in their locality during a story-writing activity.

In terms of behavior when driving on highways known for wildlife crossings, gender was the only factor influencing the likelihood of taking public transportation. Furthermore, we found no significant effects of ending types or multiple message types on participants' intention to engage in conservation. This was consistent with the findings of Niemiec et al. (2020), where message framing did not affect participants' intention to vote against wolf reintroduction, as they dismissed counterarguments presented by ranchers. In this study, the messages were focused on the elephant's journey in a fragmented landscape without presenting counterarguments or concerns from affected stakeholders. Future studies could explore the gender of the narrator and the inclusion of multiple characters representing key stakeholders, such as local communities, to portray and link the impacts of fragmented landscapes on all parties, including the elephant. While the audience expressed a willingness to support elephant conservation after participating in the CYOA activities, this study did not measure the retention of this willingness over time. Retention could be influenced by the social environment and future encounters with wild elephants.

4.4 Synthesis

Our results show that the CYOA story approach is both engaging and effective in enhancing comprehension, fostering engagement, and encouraging behavioral and perception changes concerning HEC. For example, participants showed significant improvement in the accuracy of their answers to the question of why elephants crossroads after engaging with the story. This suggests that interactive learning methods, such as CYOA activities, can facilitate learning and foster positive attitudes toward elephants by actively involving participants in the narrative (Bruner, 1986; Young & Monroe, 1996). However, the impact of CYOA activities on actual conservation engagement was negligible, possibly due to limitations in the storyline. The story did not adequately highlight the consequences of HEC on other key stakeholders, which could have limited its effectiveness in motivating participants to take conservation action (Niemiec et al., 2020). More research is needed to test the effects of CYOA on the intention to engage in conservation by including multistakeholder perspectives into the storyline to enable an understanding of the multidimensional impacts of HEC. Additionally, improvements to the online version of the CYOA story, such as adding voice narration, could further improve the interactive experience and potentially increase its effectiveness.

Implementing the CYOA activity approach in other topics and contexts presents several challenges. For instance, translating complex conservation information into interactive elements requires the educator to have a deep understanding of the learning outcomes associated with different narrative paths. For example, in our study, each decision path led to a specific learning outcome, but participants had to restart the story to explore alternate scenarios, and the effect of this restarting process was not measured. In addition, participants following different paths might experience inconsistent or incomplete learning outcomes. To address this, future CYOA activity designs could include a learner profile that tracks lessons learned and maps them to the story's educational objectives. Another challenge is to create a story with decision-making points that accurately reflect real-life situations. In our study, the decision tree for elephant behaviors was informed by extensive research on HEC and elephant movement ecology, but such detailed information may not be available for all species or ecosystems where conservation is urgently needed. Nonetheless, this gap highlights the need for future research to focus on the importance of understanding animal behavior and ecology in conservation efforts. Furthermore, crafting survey questions that accurately capture the lessons learned is also challenging. We suggest that future studies incorporate periodic questionnaires to assess memory retention over short, medium, and long terms. While this study highlighted the benefits of the CYOA teaching method through a paired test—comparing participants' perception, learning, and conservation engagement with and without the CYOA activity—these findings should be supplemented by quantitative comparisons of the efficiency of CYOA against other educational methods.

Storytelling is a powerful tool in conservation education, balancing the accuracy of information with mechanisms of engagement, especially for nonexpert audiences (Avraamidou & Osborne, 2009; Dahlstrom, 2014). The CYOA approach has the potential to promote engagement in conservation and build awareness of complex conservation issues by reinforcing the consequences of actions. This method also encourages a perspective shift through the exploration of different paths, promoting creative problem-solving while learning about alternative decisions that lead to different outcomes (Dincelli & Chengalur-Smith, 2020). By simulating direct experiences, CYOA storytelling can better prepare communities that are prone to conflicts with wildlife for potential encounters, increasing their willingness to coexist in shared landscapes.

Some questions arise from the results of this study that must be addressed before CYOA stories can be effectively replicated in other educational contexts, especially to foster engagement in conservation: (1) How can scientific language and evidence be simplified in a story without compromising the rigor and accuracy of information? (2) How can information and learning outcomes be standardized across stories created by different educators and between online and physical settings? (3) How well would participants communicate what they learn from the activity? Tackling these questions requires an in-depth analysis that incorporates pedagogical, social, and environmental perspectives, ensuring that CYOA stories can be a reliable and impactful tool in conservation education.

4.5 Further studies

Future research could explore the cultural adaptability of storytelling approaches, examining how different narratives and storytelling techniques resonate with diverse audiences, including those from various ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Social factors exert a significant influence on how people perceive human–wildlife conflicts (Dickman, 2010), making it imperative to adopt more innovative and interdisciplinary approaches to wildlife mitigation strategies. This study highlights the potential of CYOA storytelling in conservation education. Another avenue for future study could involve longitudinal research to assess the long-term impact of CYOA storytelling on attitudes, engagement, and decision-making related to conservation. This would also include measuring the sustainability of engagement over time. Furthermore, investigating the potential scalability of CYOA storytelling through digital platforms, social media, or mobile applications could help reach larger and more diverse audiences. Exploring the effectiveness of incorporating interactive technologies, such as virtual or augmented reality, into CYOA storytelling for conservation education is another promising area. Such research could determine whether immersive experiences further enhance engagement and behavioral change. Finally, examining the transferability of the CYOA storytelling method to other domains beyond conservation, such as public health, disaster preparedness, or environmental policy, could offer insights into its broader applications and effectiveness.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the engaging and effective nature of the CYOA storytelling approach in enhancing education about elephant movement ecology, behavior, and HEC. While our findings highlight the potential benefits of interactive teaching styles and the positive outcomes of participant engagement, several challenges remain that warrant further exploration. Replicating this approach across diverse topics and contexts will require addressing issues such as simplifying scientific language without compromising accuracy, assessing the impact on understanding complex issues, standardizing learning outcomes, and evaluating the effective communication of knowledge gained. Further studies could expand the application of the CYOA method to a wider range of educational disciplines, adapt narratives for diverse audiences, evaluate long-term impact, explore immersive technologies, and investigate its applicability beyond conservation. By addressing these considerations, we can continue harnessing the art of storytelling to balance accuracy and engagement, ultimately fostering greater engagement and awareness in environmental education.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Cedric Kai Wei Tan: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Yen Yi Loo: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Aina Amyrah Ahmad Husam: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Adeline Hii: Data curation; formal analysis; methodology; writing—review and editing. Ee Phin Wong: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the performers and the animators of this CYOA activity. Yayasan SIME Darby funded the project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of the study will only be made available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical limitations.