An integrated historical study on human–tiger interactions in China

中国人虎互动关系的综合性历史研究

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Zhihong Cao, Yu Li, and Saud uz Zafar contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

enTigers (Panthera tigris), as apex predators, play a crucial role in maintaining ecological functions within their ecosystems. Human–wildlife conflicts, particularly human–tiger conflicts (HTCs), have been a prevalent and severe issue in tiger-range countries from ancient times to the present day, with various regional characteristics. This article discusses human–tiger interactions in China, including different types of HTCs throughout history and the various measures implemented to promote human–tiger coexistence. Employing a historiographic approach, this study is based on case studies. It relies on historical documentation as its primary source, using methods such as literature analysis, digital humanities techniques, and field investigations. The results reveal various forms of direct negative human–tiger interactions, ranging from mild to intense HTCs, as well as other interactions such as tiger trade, medicinal use of tiger parts, and tiger habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation and urbanization, all of which have led to reductions in tiger populations. Meanwhile, the study also identifies different conceptions and measures for human–tiger coexistence amidst conflicts, including animal protection and tiger worship in China's history, and modern conservation efforts such as the inclusion of tigers on protection lists, bans on tiger medicine and trade, and the establishment of nature reserves and national parks to protect tiger habitats.

摘要

zh老虎(Panthera tigris)作为食物链顶端的捕食者,在维持其生态系统内的生态功能方面发挥着至关重要的作用。人类与野生动物的冲突,尤其是人虎冲突(HTCs),自古至今一直是老虎原产国普遍存在的严重问题,具有不同的区域性特征。本文探讨了中国的人虎互动情况,包括历史上不同类型的人虎冲突以及促进人虎共存的各种措施。该研究主要以历史文献作为主要资料来源,采用历史学方法,基于不同的案例研究进行综合分析,具体研究方法包括文献分析、数字人文技术和实地考察等。研究结果揭示了各种直接和间接的人虎冲突:直接人虎冲突包括一般性人虎相遇冲突和激烈的虎患冲突,间接人虎冲突包括虎产品贸易、虎产品药用、森林砍伐和城市化导致的虎栖息地丧失和破碎化等。这些消极的人虎互动导致了虎数量的减少。与此同时,本研究还探讨了在冲突中实现人虎共存的理念和措施,包括历史上的动物保护理念和虎崇拜现象,以及现代的保护措施,如将虎列入保护名单、禁止虎产品药用和虎产品贸易、设立自然保护区和国家公园来保护虎及其栖息地等【翻译: 曹志红】。

Plain language summary

enTigers are important for maintaining ecological balance within their ecosystems as top predators in the food chain. Human–wildlife conflicts, including conflicts between humans and tigers, have been a global issue for centuries. This paper explores both negative human–tiger conflict (HTCs) and positive (coexistence) human–tiger interactions across different periods in China's history. The research employs a historiographic approach, using case studies based on historical documentation, literature analysis, digital humanities techniques, and field investigations. It identifies both mild and intense direct negative interactions, such as tiger hunting and tiger attacks, and indirect interactions, including medical use, tiger trade, and habitat loss, all of which have led to population declines. Concurrently, the article also highlights positive conceptions and measures for human–tiger coexistence amidst conflicts, such as animal protection and tiger worship in China's history, alongside modern measures like trade bans, the establishment of conservation principles, and habitat preservation through nature reserves and national parks. This comprehensive study underscores the importance of understanding historical dynamics and implementing effective conservation strategies to reduce human–tiger conflicts and ensure the sustainability of tiger populations.

简明语言摘要

zh老虎是生态系统中食物链顶端的捕食者,对于维持生态平衡至关重要。人类与野生动物的冲突,包括人与老虎之间的冲突,已经是一个跨越世纪的全球性问题。本文探讨了中国历史上不同时期的人虎互动,既包括负面的人虎冲突(HTC),也包括积极的人虎共存。本研究主要以历史文献作为资料来源,基于历史学方法论,对不同区域的人虎互动情况进行个案研究,并在此基础上进行集成性的综合分析。本研究具体运用的研究方法是文献分析、数字人文和实地考察等。本研究揭示了人虎直接接触的“猎虎/打虎”和“虎患”为代表形式的一般性人虎冲突和激烈的人虎冲突,也探讨了虎产品的药用、虎产品贸易和虎栖息地丧失等间接的人虎矛盾,这些人虎之间的消极互动导致了老虎数量的下降。与此同时,文章还强调了在冲突中实现人虎共存的积极观念和措施,如中国历史上的动物保护理念和虎崇拜,以及现代的虎贸易禁令、保护立法和通过设立自然保护区和国家公园保护栖息地等。该综合研究旨在阐明,理解历史时期的人虎互动情况对于实施有效的虎种群保护策略、减少人虎冲突、确保老虎种群可持续性存续具有极端重要性。

Practitioner points

en

-

To promote harmony between humans and tigers in China, it is essential to analyze and understand their historical relationships to create effective conservation strategies and patterns of conflict and coexistence.

-

Strict legislative actions and measures addressing direct and indirect negative interactions, such as habitat loss and the illegal trade of tigers and their products, should be implemented continuously to safeguard tiger populations and their habitats from further decline.

-

Community engagement and cultural understanding are vital for tiger conservation. It is essential to collaborate with local people, respect their traditions regarding tigers, and raise awareness among them for sustainable coexistence. Along with that, International communication and cooperation are crucial for establishing ecological corridors for tiger survival.

实践者要点

zh

-

在中国,促进人虎和谐共处,梳理二者在历史时期的互动关系尤为重要。只有了解其历史过程的演变,才能制定有效的老虎保护策略,正确处理直接或间接的人虎冲突,设计合理的人虎共存模式。

-

保护虎种群及其栖息地免受进一步衰退的威胁,应针对导致直接和间接人虎负面互动的影响因素进行严格立法,并采取相应措施对虎种群进行持续性保护。例如针对虎栖息地的丧失、虎及其制品的非法交易等应持续严格立法并贯彻执行。

-

社会参与和文化理解对虎的保护至关重要。虎的保护应与虎栖息范围内的当地居民合作,尊重其与虎相关的文化传统,提高他们对人与虎可持续共存重要性的认识。同时,国际交流与合作对于建设虎种群可持续保护的生态走廊至关重要

1 INTRODUCTION

Humans and wildlife interact in complex ways, encompassing both positive and negative interactions, including different forms of conflict and coexistence (Nyhus, 2016). The dynamic nature of human societies, marked by unprecedented population growth and technological development, has led to profound changes in the nature and characteristics of human–wildlife interactions over time. Historical analyses of how these relationships have evolved are crucial for understanding how to protect threatened wildlife and promote harmonious human–wildlife coexistence.

As the largest terrestrial carnivores and apex predators in the food chain, tigers (Panthera tigris) play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity within their ecosystems, and they interact with humans in complex ways. Throughout history, human–tiger conflicts (HTCs) have been a prevalent issue across the species' range. Fundamental forms of HTCs include the predation of livestock and attacks on people by tigers, which often lead to retaliatory killing and a pervasive fear of tigers. HTCs are highly variable, exhibiting distinct features across different regions and countries. For example, in Nepal, human fatalities and livestock depredation remain the primary manifestations of HTC (Dahal et al., 2020). In India, the increasing human and livestock population around tiger reserves frequently results in HTCs, reflecting heightened competition for living space and resources between humans and tigers (Chouksey & Singh, 2018). Beyond these direct HTCs, tiger range countries are facing severe environmental challenges and degradation of tiger populations due to human population growth, rapid economic expansion, urbanization, massive infrastructural development, and climate change. The overarching challenge of tiger conservation, and biodiversity conservation in general, is that there is insufficient societal demand for the protection of wild tigers in natural landscapes (Seidensticker, 2010). Negative human–tiger interactions, such as retaliatory killings, tiger trade (Villalva & Moracho, 2019), and habitat loss and fragmentation, have made survival increasingly difficult for tigers, causing their numbers to decline rapidly. Currently, the global tiger population is estimated to range from 3726 to 5578 individuals, distributed across 10 countries. Tigers of different subspecies are listed as endangered or critically endangered (CR) (Goodrich et al., 2022).

China has historically been an important part of the tiger's range. Four subspecies of tiger used to occur in China: Bengal tigers (P. tigris tigris), Indochinese tigers (P. tigris corbetti), Amur tigers (P. tigris altaica), and South China tigers (P. tigris amoyensis). Currently, the first three subspecies still exist in the wild and in zoos/parks, while South China tigers only survive in captivity (Jinfeng et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). In the past, tigers were widely distributed throughout China. As one of the ancient totemic animals, tigers symbolized power, bravery, and protection against evil. They were also thought to bring blessings. Tigers have always been closely intertwined with the development of Chinese history and culture, and tiger culture is an indispensable element of modern Chinese culture (Zhihong, 2010). HTCs have occurred throughout Chinese history, varying in severity due to different factors (Xingliang, 2009). However, with diminishing habitats and deteriorating living conditions of tigers, the expansion of the tiger product trade and medicinal use, and the development of agriculture, industry, and urbanization, the relationship between humans and tigers has become increasingly tense. As of July 2022, the estimated number of wild tigers in China was just 73, accounting for only 1.3%–1.9% of the global population (China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation, 2022). All tiger subspecies in China are classified as CR (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People's Republic of China, 2023).

Countries and regions worldwide have implemented various measures to conserve tigers. In China, these measures include banning the medicinal use and trade of tigers, promoting alternative medicinal substitutes, prohibiting the hunting of tigers, and establishing natural reserves and national parks. Due to the low population of tigers, direct HTCs, such as tigers attacking humans and humans killing tigers in retaliation, have become rare in China. Consequently, tiger habitat management and conservation have become the major focus for ensuring human–tiger coexistence in the country.

This study examines the history of human–tiger interactions in China from a long-term perspective. Using historiography approaches, we analyze human–tiger conflicts and the measures taken to ensure human–tiger coexistence throughout history up to the present day. By improving our understanding of past human–tiger interactions, we can explore more effective ways to protect this species from extinction and preserve ecological balances in tiger ecosystems.

2 STUDY PERIODS AND REGIONS

This research spans a long-term perspective from the Prehistoric era to the present day. This approach allows us to estimate tigers' overall population trends and geographical distribution while facilitating a macroscopic understanding of the changes in human–tiger interactions over different periods.

The geographical scope of this research covers the entire territory of China. However, given the vast land area, significant regional variations, uneven development levels, and the characteristics of historical documentation, this study primarily focuses on Northeast China (comprising Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning provinces), Xinjiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Southern Shaanxi.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Materials

The research materials primarily consist of archeological data, including tiger fossils and bones, historical tiger records, gazetteers, and tiger reports.

Historical tiger records were collected and organized from several literature sources, including official history books, political and literary works, encyclopedism reference books, novels, poetry collections, tablet inscriptions, and medical books. These sources were accessed in both paper and electronic formats. Electronic literature sources include: (1) Hanji Quanwen Jiansuo Xitong 汉籍全文检索系统 (Chinese Historical Literatures Full-text Retrieval System, fourth edition), (2) Wenyuan ge Siku Quanshu (Electronic Edition) 文渊阁四库全书电子版 (Complete Library of the Four Branches), and (3) Zhonghua Yidian 中华医典 (Encyclopedia Database of Chinese Traditional Medical Books, 5th edition).

For gazetteers, the main sources were the Zhongguo Fangzhi Congshu 中国方志丛书 (Gazetteers of China) and the Zhongguo Difangzhi Jicheng 中国地方志集成 (Compilation of China's Gazetteers). In addition to these sources, we visited libraries in certain regions to access local chronicles not included in the aforementioned series. A total of 221,500 words of tiger-related records were obtained for this research from these gazetteers' chronicles.

Details about these major materials information can be found in the Supporting Information.

3.2 Approaches and methods

This integrative research is based on case studies. Hence, the study is founded on a comprehensive analysis of regional case studies used to analyze human–tiger interactions throughout China's history and to categorize human–tiger coexistence measures from past to present. The research methodology involves a combination of literature analyses, digital humanities (DH) methods, and field investigations. Regarding literature analysis, the first step was to collect records about tigers from Chinese historical documents. These records were then processed and digitized to establish databases with different topics for analysis. Field investigations supplemented the analysis of historical literature, allowing direct observation of geographical conditions and current scenarios of HTCs. Further details about the methodologies employed in this study are provided in the Supporting Information S1.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Different types of human–tiger interactions from China's history

In China's history, negative human–tiger interactions can be divided into two categories: direct and indirect interactions (Table 1).

| Category | Habitat | Event | Encounter intentionality | Reason/Purpose | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human–tiger negative interactions | Direct interactions | Nonoverlapping | Hunting of tigers | Intended | Entertainment; soldier training; official selection | Killing of tigers |

| Human–tiger encounters during people's occasional farm work in mountain areas; passing by forests, and so on | Unintended | For safety and self-protection | Human–tiger fighting killing of tigers killing of people | |||

| Overlapping | Attacks by tigers | Intended | For food and prey | Killing of livestock and people | ||

| Hunting and killing of tigers | Intended, planned/organized | By people, military, or government | Killing of tigers | |||

| Indirect interactions (hidden, invisible) | Either | Trade of tiger parts | Intended | For money/health/entertainment/authority | Killing of tigers | |

| Tiger medicinal usage | Intended | For health | ||||

| Either | Deforestation, modernization, industrialization, urbanization | Intended | For people's development | Tiger habitat fragmentation and/or loss tiger population reduction and decline |

These human–tiger negative interactions are derived from several case studies spanning different eras and regions, using the materials and approaches outlined above.

Direct interactions refer to encounters between humans and tigers, resulting in tiger attacks on humans and/or livestock and humans retaliating by hunting/killing tigers in return, often as an act of revenge. Such scenarios can differ; encounters were often unintended when people and tigers lived in separate areas (nonoverlapping habitats). For safety and self-protection, both people and tigers would fight each other. In some cases, tiger hunting was merely a form of entertainment. However, when human and tiger habitats overlapped, tigers tended to attack people or livestock, leading to intentional encounters. These included government-sanctioned killings when attacks became intense, causing drastic drops in tiger populations.

Indirect negative interactions occurred during both habitat overlap and nonoverlap periods. These included interactions for health purposes and profit from tiger medicine and trade. This demand for tiger parts led to additional tiger hunting/killing. Tiger habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from modernization, urbanization, and industrialization also led to indirect negative interactions.

In different historical periods, each type of interaction had different scenarios and varied in intensity. Specific events, their reasons, and results are discussed below.

4.1.1 Tiger hunting for entertainment, soldier training, and official selection

Hunting has been an integral part of human culture since the early days of our species. In prehistoric times, people hunted wild animals for safety and sustenance, with tigers among the targets. As societies and economies developed, tiger hunting evolved beyond necessity into a form of entertainment, a means for soldier training, and a method for selecting martial officials. The fierceness and difficulty in capturing tigers made them ideal for these purposes. Capturing and killing tigers became a recruitment test for soldiers and officials. With advancements in science and technology, hunting tools improved, making tiger hunts easier and less risky. These developments increased the number of hunts and significantly impacted tiger populations.

In the ancient Chinese chronicle Zuo Zhuan 左传 (1999), different seasonal hunting activities are mentioned as follows: “Spring hunting (春蒐 chūn sōu) is to search for nonegg-laying and nonpregnant birds and animals; Summer hunting (夏苗 xià miáo) targets birds and animals that harm crops. Autumn hunting (秋狝 qiū xiǎn) is conducted in harmony with the autumn atmosphere of solemnity. Winter Hunting (冬狩 dōng shòu) refers to hunting various birds and animals that are fully grown and can be indiscriminately encircled and hunted. All of these activities took place during the agricultural downtime” (Zuo Zhuan, 718 bce). These descriptions demonstrate that people at that time were aware of ecological processes in their hunting activities, including an explicit mention of human–wildlife conflicts in the form of crop raiding. It also indicates that organized hunting activities had a military exercise nature, serving not only as a means of hunting but also as training exercises. These activities, especially among emperors or tribal leaders, were designed to reduce fear and promote quick decision-making during sudden, uncontrolled attacks by enemies.

King Wu of the Zhou Dynasty (11th century bce) was deemed a “tiger-hunting hero.” According to records, King Wu hunted 22 tigers and many other animals (Yi Zhou Shu 逸周书, 1999). Later, King Mu of the Zhou Dynasty was also recorded to have hunted a tiger in Hulao Pass (also known as Tiger Cage Pass, named after this tiger hunting event) in Central China's Henan Province (Guo, 1989).

During the sixth to fifth century bce, King Zhuang of Chu State sought talented individuals through hunting, with tigers as one of the targeted animals. He proclaimed that if someone could kill tigers and leopards with hazelwood, they were brave; if someone could wrestle with rhinoceroses bare-handed, they were strong; and if, after the hunt, someone could fairly distribute the spoils to everyone, they were virtuous. By employing this method, King Zhuang successfully recruited various talents (Yuanjun, 1979).

Some dynasties founded by nomadic tribes, such as the Khitan-led Liao Dynasty (90–1125 ce) and the Jurchen-led Jin Dynasty (1115–1234 ce) in northeast China, excelled at hunting. Their rulers preserved the tradition of hunting as a means to demonstrate their martial spirit. It is recorded that Emperor Xingzong of Liao encountered three tigers during a hunting expedition and captured them with his dogs in 1024 ce (Tuotuo, 1974). Similarly, Emperor Zhangzong of Jin shot a tiger with a bow and arrows while hunting in the Qiu mountains (Tuotuo, 1975).

In the Qing Dynasty, tiger hunting served as a way for emperors to train and cultivate military skills among the Eight Banners leaders and soldiers. Royal tiger hunting by the Qing emperors was an activity carried out to display their martial prowess and heroic demeanor. One of the most notable emperors known for tiger hunting was Emperor Kangxi (康熙). During Emperor Kangxi's journey to Shengjing (present-day Mukden or Shengyang) in his 20th year (1681 ce), he hunted multiple tigers he encountered along the way. According to incomplete statistics, Emperor Kangxi personally hunted and killed approximately 135 Amur tigers in the northeastern region between 1662 and 1719 ce (Shizun, 2005), which was a huge number for that era.

In early modern times, Westerners also participated in tiger hunting in China's Xinjiang region. For example, in 1885, Russian military explorer Nikolay Mikhailovich Przhevalsky (Никола́й Миха́йлович Пржева́льский) visited Lop Nor for the second time and documented the local hunting customs of the Lop people, including various methods of tiger hunting. During his stay in the village of New Abu Dar, he participated in multiple local tiger hunting activities and once witnessed a tiger “running away without any injuries” (Przhevalsky, 1879, Chinese translation 1999).

4.1.2 Mild HTCs: Tiger attack and tiger killing due to occasional encounters

Encounters between humans and tigers were generally rare in China, mostly due to differences in habitat preferences. However, such encounters did occur when a tiger entered human-inhabited areas, causing disturbances to people's lives and resulting in mild forms of HTC. For example, in 1363, during the Yuan Dynasty, a tiger entered the downtown area of Lianjiang County. The following year, a tiger was captured in Fuzhou Prefecture, and in 1511, during the Ming Dynasty, a tiger unexpectedly climbed onto residents' houses and was shot by an official with a bow and arrows in the same prefecture (Jingxi et al., 1751).

Conversely, when people occasionally passed through forests or entered forested areas for production activities, encounters with tigers also led to HTCs. For example, in 1193, during the Southern Song Dynasty, a female villager was collecting bamboo shoots when she was attacked and eaten by a tiger on Shigu Mountain in Gutian County, Fujian (Mai, 2006). Another person named Lin Detai killed a tiger when he encountered one passing through a forest before the year 1496 during the Ming Dynasty in Yongchun County (Qiaosong et al., 1927).

4.1.3 Intense HTCs: Violent tiger attacks and tiger killing due to habitat overlap

As human agricultural and industrial activities developed and populations expanded into China's mountainous regions, where tigers and their habitats were more prevalent, the overlap of human and tiger habitats increased. This overlap intensified competition for land and resources, compressing the tigers' habitats and leading to more frequent and intense HTCs. These conflicts became especially pronounced during the later periods of China's history, from the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912 ce) onward.

Southern Shaanxi (including the cities of Hanzhong, Ankang, and Shangluo) is a vast mountainous region that transitions from the northern subtropical zone to the warm temperate zone. It is bordered by the Qinling Mountains in the north (with an average altitude of approximately 2000–3500 m) and the Bashan Mountains in the south (with an average altitude of approximately 2000–2500 m). This region, characterized by dense forests and numerous rivers, serves as the transitional zone between northern and southern China. The mild and humid climate provides excellent natural conditions for the survival of various animals, including tigers.

Southern Shaanxi's unique natural environment and abundant resources have historically attracted people seeking land for expansion or refuge from wars. The development of Southern Shaanxi can be categorized into five stages (Liangxue, 1998). Before the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 ad), the development activities were primarily limited to basic crop cultivation in river valleys, basins, and low mountainous areas by local indigenous residents. The activities were sporadic and limited in breadth and depth, with minimal impact on the local ecological environment. Under such development conditions, the habitat of tigers remained relatively undisturbed, tiger numbers were relatively abundant, and HTCs only occurred occasionally.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912 ce), Southern Shaanxi became one of the core areas for both official and unofficial migration, with Hubei, Hunan, Fujian, and Guangdong as the main sources of immigrants. This influx led to extensive land reclamation and profound changes in the region's mode of production. The immigrants engaged in agricultural cultivation and participated in industries such as coal mining, gold mining, charcoal burning, papermaking, and tea production. They gradually expanded their activities from the river valleys and plains to the low hills, then to the middle mountains, and finally to the high mountains and gorges. For decades, forests were cleared and burned, and the landscape of mountains and rivers was significantly altered (Zhiyi, 1842). This intensive development led to severe environmental changes and the destruction and loss of tiger habitats.

In the 55 gazetteers of Southern Shaanxi, two tablet inscriptions, as well as four related series and anthologies, a total of 83 tiger records were collected. Among these, 74 were from the Ming and Qing periods, and nine were traced back to previous dynasties. Of the 74 records, 31 were related to HTCs, including 11 mild conflicts and 20 intense ones. According to these records, tiger attacks occurred quite frequently during the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty and the mid-Qing Dynasty, mainly coinciding with peak periods of local development. In addition, there were instances where tigers appeared in groups to attack local people, extending their attacking range and causing severe injuries that threatened the daily lives of residents. Therefore, government officials began to offer substantial rewards for tiger hunting/killing. Of the 31 HTC records, 15 provided detailed descriptions, and nine involved government-organized tiger hunting efforts. Such hunting efforts were the main approach to preventing tiger attacks and mitigating the threat posed by tigers to local communities.

Tiger attacks were particularly severe in the mountainous areas of Xixiang County. During the Wanli reign (1573–1620) of the Ming Dynasty, a group of tigers began by preying on cattle and sheep in open land, then targeted pigs and dogs in villages, and eventually escalated to attacking and injuring people both day and night. Later, in 1712, during the Qing Dynasty, the tiger menace resurfaced, surpassing all previous instances. This time, tigers not only roamed the outskirts but also entered the city at midnight, harming people and causing livestock losses (Bingran, 1813).

In response, Prefect Wang Mu organized government-led tiger hunts, offering a reward of 100 strings of money for each tiger killed to the professional tiger hunters recruited for the task. These professional hunters were familiar with the tigers' paths and various tiger-hunting tools, including bows and arrows, hidden arrows, and spears. Their efforts proved successful, as it was recorded that “From 1713 to 1715, 64 tigers were killed and others were wounded as well” (Tinghuai, 1828).

Compared to individual tiger hunting, these government-led tiger eradication efforts were more effective in addressing the immediate threat posed by tigers and resulted in a rapid decline in the local tiger population. For example, numerous records indicate that “tiger attacks happened quite often during the Qianlong Emperor's reign (1736–1795). However, it is rare to see any tiger recently (1926) due to the cultivated wasteland expansion” (Zhonghuang, 1926).

4.1.4 Indirect negative interactions: Tiger habitat loss due to modernization and industrialization

The Amur tiger, which occurs in Northeast China, the Russian Far East, and the Korean Peninsula, has historically coexisted with humans since the Paleolithic Age. This area, which includes the Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, covers an area of approximately one million square kilometers. It features high mountains, dense virgin forests, abundant rainfall, and rich biodiversity, providing an excellent habitat for the Amur tigers (Excavation Team of Gezidong Site, 1975; Guoqin, 1989; Jiang, 1975, 1982; Jianzhong et al., 1981; Joint Jin-Niu-Shan Excavation Team, 1976; Chinese Archaeology Society, 1997a, 1997b; Xinxue et al., 1984; Xueshi & Guanfu, 1973; Zhenhong, 1981; Zhenhong et al., 1980; Zhenhong et al., 1985; Zhuowei et al., 2003; Zhuchen, 1947).

During ancient times, Northeast China was mostly inhabited by minority ethnic groups with nomadic lifestyles centered around hunting and gathering. Occasionally, agricultural regimes took control of these areas, but continuous agricultural production was not implemented. Thus, before the mid-19th century, except for some forest loss in the western and southern parts of Liaoning Province and the middle and lower reaches of the Yalu River, most of the region was still covered by dense virgin forests, with the overall forest coverage rate exceeding 70% (Zhongwen et al., 2009). As the birthplace of the Qing rulers, the northeast region was protected as a preserved area through a policy of isolation that forbade people from different areas from moving in for farming or hunting. This policy helped maintain the integrity of the forests and the wildlife they supported. In the early years of the Qianlong reign (1735–1795), it was recorded that tigers were found “in all the mountains of the Northeast” (Qinding Shengjing Tongzhi, 1965).

The modernization of Northeast China began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by Russia and Japan. In 1860, Imperial Russia forced the Qing government to sign the Sino-Russian Treaty of Beijing, which marked the intervention and influence of external powers in the region, driving the subsequent modernization process. In 1898, Russia leased the territories of Port Arthur and Dalian from China and began constructing ports and railroads. In 1897, Russia began the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway, which traversed the most densely forested areas of Northeast China. Russian settlements and logging operations were established along the railway line, extensively exploiting China's forestry resources. “By 1915, there were 22 Russian forest stations along the Chinese Eastern Railway, occupying an area of approximately 19,700,000 hectares” (Zhongwen et al., 2009). The primary function of the Chinese Eastern Railway was initially to transport timber, serving as a major transportation route for Russia's exploitation of Northeast China's forest resources. After the depletion of timber resources along the Chinese Eastern Railway, Russia built the South Manchuria Railway and dozens of forest railways, intensifying this exploitation of China's forest resources.

In 1905, following Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War, it acquired Russian interests in Northeast China through the Treaty of Portsmouth. Japan began promoting modernization and colonial rule in the region, developing industries, mining, and transportation infrastructure while engaging in the exploitative industrial development of its coal, iron, timber, and other natural resources. After 1931, Japan occupied Northeast China, established the puppet state of Manchukuo, and intensified colonial rule. Japan felled large amounts of timber for military installations and transported significant quantities of high-quality timber back to Japan. During Japan's colonial rule in Northeast China (1931–1945), approximately 100 million cubic meters of timber were plundered and transported to Japan (Zhongwen et al., 2009).

The Russian and Japanese indiscriminately exploited and deforested Northeast China, causing irreversible damage to its forests. Mountainous regions were severely fragmented, threatening tigers' survival in the region. By the early 20th century, the presence of Amur tigers in Liaoning Province had already become scarce. It is recorded that “the tiger is rarely seen” (Xijue & Mingshu, 1930), suggesting a significant decline in the Amur tiger population (Yu et al., 2009).

4.1.5 Usage of tiger parts in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

In TCM, almost every part of the tiger's body is believed to have unique medicinal properties. These parts include tiger bones, fat, meat, blood, stomach, gallbladder, kidney, skin, eyes, whiskers, brain, claws, teeth, nose, feces, and tail, all of which are used as medicinal ingredients with different therapeutic effects. For example, historically, it was believed that a tiger's tail could treat various skin diseases, tiger bile could treat children's spasms, tiger whiskers could relieve headaches, and tiger brain could treat laziness and acne (Shenwei, 1108; Shen, n.d.). Among the tigers' organs and body parts, bones were considered to have the highest medicinal value.

The use of tiger bones as medicine can be traced back over 1000 years. According to the Shiliao Bencao食疗本草 (Materia Medica of Food Therapy, written in 713–741 ad), “Tiger bones: boil them into a bath decoction to dispel wind pain, toxins, and swelling due to bone-joint disorders. Soak them in vinegar and apply to the knees to alleviate foot pain and swelling. The shinbone is the most effective. The decoction can also be used for bathing newborns, expelling evil qi (vital energy), treating ulcers, scabies, epilepsy, demonic possession, and ensuring healthy growth.” Therefore, “The hunter is likely to get it (tiger) and sell it at the highest market price. Its skin can be used as a mattress, and its bones can be made into medicinal wine, which is most effective in treating back and leg pain and other ailments” (Weiqing et al., 1935).

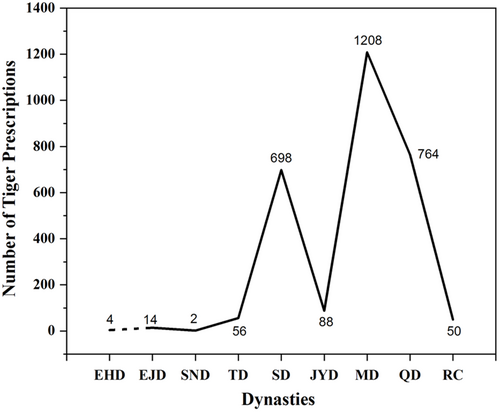

In the Zhonghua Yidian 中 华 医 典 (5th edition) (a large-scale electronic compendium of ancient Chinese medical texts), there are 2996 pieces of medicinal information about tiger products and 2884 prescriptions involving tiger parts. Through comprehensive analysis, we found that the earliest recorded literature on the medicinal value of tiger products in China can be traced back to the pharmacological work Mingyi Bielu 名医别录 (Records of Famous Physicians) from the end of the Han Dynasty (Before 220 ce [Figure 1]). By the Han Dynasty, people already had a basic understanding of the medicinal value and therapeutic uses of certain tiger parts. According to the available literature, the use of tiger-based prescriptions first appeared during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 ce) and no later than the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420 ce). The number of prescriptions increased rapidly during the Jin 晋 (265–420 ce), Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589 ce), and Tang Dynasty (618–907 ce), and reached its first peak in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 ce). During the Jin 金 (1115–1234 ce) and Yuan Dynasties (1271–1368 ce), the number of prescriptions dropped significantly, but prescription numbers experienced another peak during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 ce), making it the period with the highest number of recorded tiger-base prescriptions in history. Although there was a slight decrease during the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912 ce), the number of tiger-based prescriptions remained higher than that of the Song Dynasty. In the Republican era (1912–1949 ce), the number of tiger-based prescriptions decreased to a level nearly equivalent to that of the Tang Dynasty. Traditional Chinese medicine's utilization of tiger products for over 2000 years has been based on the hunting and killing of tigers, actions which undoubtedly have had a very negative impact on tiger populations.

4.1.6 Tiger trade and hunting

Tigers, as a resource with multiple utilitarian values, have been highly regarded throughout history due to their uniqueness and scarcity. Thus, interest in tigers and their parts has been common among ordinary people, the nobility, and elite rulers alike in tiger-range countries. This widespread fascination led to tigers and tiger parts becoming trade commodities.

In ancient times, when the commodity economy was not well developed, tiger trade was uncommon, and tiger products were mostly used as tributes, gifts, or for simple barter. Tiger skin was likely one of the earliest tiger products traded. Its stunning appearance, warmth, fine and thick fur, large size, and unique colors and patterns made it highly sought after for clothing, carpets, and decorations, signifying the prestige of the owners. Some rulers and upper-class individuals were willing to purchase tiger and leopard skins at high prices to display their privileged status.

Tiger skin was also used as tribute from minority ethnic tribes to China's central government to seek rewards or protection. In 49 ce, it was recorded that the Wuhuan leader led a crowd to submit and pay tribute to the Eastern Han Dynasty, presenting tiger and leopard skins along with slaves, cows, horses, and bows. The Han emperor ordered a grand feast and bestowed precious treasures on Wuhuan as a reward (Ye, 1959). Such a tributary relationship was a form of trade involving the reciprocal exchange of valuable local products.

With the development of the commodity economy, tiger products began to circulate as commodities. For some ethnic groups in remote areas with low economic development, tiger skins served as an intermediary currency in the commodity trade. For example, during the Southern Qi Dynasty (479–502 ce), the Qiang tribe did not produce any metallic currency. Instead, tiger skins, being rare and precious, were highly valued and used as intermediaries for trade (Zixian, 1972).

Earlier, we described the demand for tiger products in traditional medicine (Figure 1). Due to their high demand in TCM, tiger bones became the most widely circulated tiger product. The tiger bone trade appeared as early as the Han Dynasty and became commodified during the Tang and Song dynasties. During the Yuan Dynasty, tax rates were imposed on tiger products, and during the Ming and Qing periods, tiger skins, bones, and other products circulated locally. For example, it is recorded that in 1537, during the Ming Dynasty, a tiger skin was valued at three silver coins (Luo, 1443). The Lop Nor people in Xinjiang hunted and sold the skins and bones of Tarim tigers, marketing them locally as well. During the Guangxu period, merchants from Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Gansu collected tiger bones and skins, which were then transported by land into Xinjiang province or sold to Qitai County towns (Changjixian Xiangtu Tuzhi, 1908). Sven Hedin once purchased two tiger skins in Xinjiang Lop Nor (Hedin, 1940).

The commodity economy of Northeast China began in early modern times, leading to the gradual commercialization of tiger products and the formation of a tiger product trade market. Hunters went into the mountains specifically to hunt tigers for profit. During the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty, Sanxing County in Heilongjiang Province (now Yilan County) levied taxes based on the units of tiger bones and tiger skins (Guangxu Sanxing Xianzhi, 1890). During the Republican period, a large number of tiger products were marketed, even reaching international markets. In 1913 alone, 28 tigers were captured for their skins in Tongyuan County. These tiger skins were not for local consumption but were sent from Harbin to Beijing and Tianjin and then sold to agents of European stores (Chinese Eastern Railway Company, 1933). According to a 1927 record, the annual sales of tiger bone glue, a traditional Chinese medicine made by boiling and extracting gelatin from tiger bones, in Fengtian Province (now Liaoning Province), reached 355 kg (Shunan et al., 1934), indicating a significant market demand for tiger bone at that time.

4.2 Historical and contemporary measures for human–tiger coexistence

Human–wildlife coexistence is an urgent global concern with profound implications for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Target 4 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, agreed upon at the end of 2022 during COP 15, states: “Ensure urgent management actions, to […] and effectively manage human–wildlife interactions to minimize human–wildlife conflicts for coexistence” (Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

To discuss human–tiger coexistence, it is essential to clarify the perspectives and contexts for the concept of “coexistence,” as it is currently used with various interpretations, such as a desirable state, a factual occurrence, or a conservation approach. In this paper, we refer to human–tiger coexistence as “a situation where people and wildlife can both survive and flourish in shared environments” (Gao, 2023).

Currently, the tiger population in China is relatively low, which is a consequence of direct and indirect human impacts on tigers, as previously discussed. Consequently, HTCs in China are now infrequent, particularly direct forms of HTCs. In this section, we examine people's perceptions of tigers and measures to promote human–tiger coexistence in China from ancient times to the present. We explore how Chinese people historically coexisted with tigers amid conflicts, how the use of tiger parts in medicine and the tiger trade have been banned in modern times, and how China currently protects tiger habitats and wild populations.

4.2.1 Animal protection perceptions and tiger worship in China's history

Despite HTCs and the hunting and persecution of tigers, ancient China also had a culture of tiger worship and a concept of legal animal protection. These concepts and laws influenced tiger protection to varying extents at different times and in different regions.

The concept of coexistence between humans and animals was present in ancient China. In the Zhuangzi 庄子 (a compilation of Classical Philosophical Daoism of Zhuangzi and his followers), it is stated: “Heaven and earth were born alongside me, and the 10,000 things and I are one” (Zhuangzi). This reflects the ancient Chinese conception of “promoting harmony between humanity and nature” (天人合一). Influenced by this belief, there has been a long-standing tradition of protecting animals throughout Chinese history despite the conflicts between humans and animals. The Yi Zhou Shu 逸周书 mentions that “In the mountains, trees are not felled out of season to promote their growth; in rivers and lakes, nets are not cast out of season to promote the growth of fish and turtles. Birds' eggs and young animals are not taken, allowing the growth of birds and beasts. Hunting has its seasons, and no young sheep or pregnant sheep are killed. Calves do not pull carts, and colts do not run wild. The land retains its suitability, all things retain their innate characteristics, and the world follows its proper seasons.” This emphasizes the importance of “protecting and utilizing natural resources in season” (以时禁发) and protecting animals to maintain biodiversity. This regulation, issued in the 10th century bce (from the record of Yi Zhou Shu, which is a compendium of Chinese historical documents about the Western Zhou period, ~1046–771 bce), is regarded as one of the earliest forms of animal protection legislation.

During the Western Zhou Dynasty in the 11th century bce, an environmental protection decree called Fachongling 伐崇令 was issued, which stated that animals should not be harmed. Violation of this prohibition was met with severe punishment, including the death penalty (Juanli & Jiang, 2020). By the time of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 bce–220 ce), the Chinese people had already recognized the contradiction between infinite human demands on nature and limited the regeneration capacity of natural resources. Consequently, more secure and detailed animal protection regulations were formulated, specifying which animal species could be hunted and the permissible times for hunting. Violations of these regulations were met with a variety of punishments.

In ancient China, HTCs were unavoidable due to the pressures of survival and the demands of rulers and emperors. In most cases, the management goal was to keep the intensity of these conflicts at tolerable levels for both people and wildlife. Hence, besides hunting and killing, there were other ways to resolve conflicts between humans and tigers.

One such approach was using virtuous governance to subdue tigers, derived from the culture of tiger worship. From prehistoric times, tigers were regarded as a symbol of authority and bravery, as evidenced by tiger totems from 4000 to 3000 bce (Xuefei, 2018). From the Zhou Dynasty in the 11th century bce, tigers were worshiped as one of the eight agriculture gods due to their ability to prey on wild boars (Qizhi, 2008). As the king of animals, tigers were believed to confront challenges and devour demons since the Han Dynasty of the first century (Liqi, 2010). Later, in the 10th and 11th centuries, Emperor Taizu of the Jin 金 Dynasty used a piece of tiger skin on his horse's back while hunting to symbolize his authority and bravery (Wenyin, 1986).

In ancient China, tigers were also regarded as divine and auspicious creatures, embodying the moral principles of punishing evil and promoting good. The government viewed the appearance of tigers as a judgment on their governance. When tiger disturbances or attacks occurred, officials and the public considered them warnings of poor governance. Therefore, the government would adopt benevolent or virtuous governance to stop these warnings and drive the tigers away. Officials would offer sacrifices and prayers to the Cheng Huang deity, regarded as the guardian god of the city, assisting local governance. Along with the sacrifices, they would write and recite tiger articles to request Cheng Huang's help in expelling the tigers. For instance, in 1666, following the tiger attacks in Qingshui County, Shi Runzhang, the local official, composed a tiger article appealing to Cheng Huang to expel the tigers (Yi & Sunyi, 1870). In northeast China, tigers were worshiped as local deities to prevent tiger attacks.

4.2.2 Tigers' increasing legal protection

In the mid-20th century, global concerns began to rise regarding declining tiger populations due to habitat loss and hunting. Efforts were initiated to address these issues through national legislation in several tiger range countries. In 1975, tigers were included in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This listing prohibited international trade in tiger parts and products and has played a crucial role in curbing illegal poaching and trafficking. The early 1990s witnessed significant international attention and initiatives for tiger conservation, culminating in the establishment of the Global Tiger Initiative (GTI) in 2008. In 2010, the tiger range countries participated in the St. Petersburg Tiger Summit, which aimed to improve tiger habitats, strengthen antipoaching efforts, and enhance international collaborations for tiger conservation.

In 1950, the Central People's Government of China announced the Methods for the Conservation of Rare Species 稀有生物保护方法, marking the official start of wildlife protection in the People's Republic of China. Subsequently, related policies and regulations on forest protection, land resource utilization, hunting regulations, and relevant laws involving animal protection at the national level were enacted successively. These measures provided stronger prerequisites for tiger protection.

In 1959, the Ministry of Forestry of the People's Republic of China issued the Directive on Proactive Implementation of Hunting Activities 关于积极开展狩猎活动的指示, which had a contradictory approach to tiger conservation. The third article of this directive designated the Amur tiger as a rare and precious animal, prohibiting indiscriminate killing to prevent extinction, except for capturing some individuals for scientific research, exchange, and captive breeding in parks. Paradoxically, the first article encouraged hunters to eliminate harmful birds and animals that posed a threat to humans, livestock, and agricultural and forestry crops, including tigers (especially the South China tiger), bears, leopards, and wolves. As a result, the South China Tiger was not afforded any protection under this directive. In September 1962, the State Council listed the Amur tiger in the animal protection list and established nature reserves through the Directive on Proactive Protection and Rational Utilization of Wildlife Resources 关于积极保护和合理利用野生动物资源的指示. In March 1977, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry designated the Amur tiger as a first-class protected animal at the national level and the South China tiger and Bengal tiger as second-class protected animals. In 1988, China promulgated the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife 中华人民共和国野生动物保护法, which classified all subspecies of tigers as national first-class protected animals, strictly prohibiting illegal hunting. This legislation has significantly contributed to safeguarding and restoring tiger populations, as well as protecting their natural habitats. The law establishes the principles, responsibilities, legal liabilities, and management measures for the protection of wildlife and its habitats. It covers matters related to the conservation, utilization, transportation, trade, destruction, harm, rescue, and damage of wildlife.

4.2.3 Nature reserves and national park: Habitat protection for tigers

Ensuring sufficient living space and resources for tigers is an important measure to address HTCs and ensure tiger conservation. The establishment of nature reserves and national parks is an effective way to protect tiger habitats and plays a crucial role in their survival and reproduction. At present, there are seven tiger-relevant nature reserves established in the regions where the four subspecies occur or used to occur in China. For Amur tigers, there are two reserves: (1) Hunchun Amur Tiger Nature Reserve (the first national-level reserve for Amur tigers, established in 2001) and (2) Heilongjiang Laoyeling National Nature Reserve; for South China Tigers: (3) Jiangxi Yihuang Chinese Tiger Provincial Nature Reserve, (4) Jiangxi Le'an Yushan Laohunao Nature Reserve, and (5) Zhejiang Fengyangshan and Baishanzu Nature Reserve; for Indochinese Tigers: (6) Fujian Longyan Meihua Mountain Nature Reserve; and for Bengal Tigers (7) Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon National Nature Reserve.

In 2013, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China proposed the establishment of a new national park system. In 2021, at the Leadership Summit of COP 15, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the formal establishment of the first batch of five national parks, including the Northeast China Tiger and Leopard National Park. This park is located in the southern part of Laoyeling Mountain, at the junction of Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces (42°38′45″N to 44°18′36″N and 129°05′01″E to 131°18′52″E), covering an area of 1.4065 million hectares. It is the most populous, active, and important settlement and breeding area for tiger and leopard populations in Northeast China (National Forestry of China, 2017).

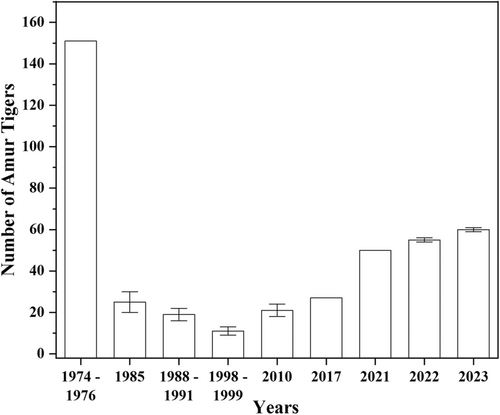

The establishment and improvement of nature reserves and national parks have led to the protection and restoration of tiger habitats, providing conditions for the return of the Amur tigers. In the 1970s, the population of Northeast Tigers was 151, but it sharply declined afterward. Since the establishment of the first Amur tiger nature reserve in 2001 and the subsequent establishment of the national park, the population of Amur tigers has shown some recovery (Figure 2).

4.2.4 Prohibition of the tiger medicine trade and scientific alternatives

Apart from HTC and the trade of tiger products, the medicinal use of tiger parts poses a significant threat to their survival. On May 29, 1993, the State Council of the People's Republic of China issued a notice titled “Prohibition of Rhinoceros Horn and Tiger Bone Trade,” which comprehensively banned the trade of rhinoceros horns and tiger bones. This notice prohibited the acquisition, utilization, import, and export of tiger bones and derived products. It also canceled the medicinal standards of tiger bones and removed them from the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Furthermore, the use of formulations containing tiger bones was prohibited. This policy put an end to China's 1000-year history of using tiger bones in medicine and halted the trade of tiger products, allowing tigers to live and reproduce. Since the ban, efforts have been made to develop artificial alternatives to tiger-based medicines.

5 CONCLUSION

Throughout different historical periods in China, both negative (HTC) and positive (coexistence) human–tiger interactions have existed. The negative interactions can be divided into direct and indirect, and there have been distinct phases of these negative interactions throughout China's complex and rich history. In ancient times, direct conflicts were mainly sporadic encounters between humans and tigers, which were relatively mild. During the Middle and Late Middle Ages, human habitats began to overlap with those of tigers, leading to an intensification of direct conflicts and state-sponsored tiger hunting activities, particularly during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In modern times, habitat fragmentation due to urbanization and modernization has become the main cause of tiger population declines in China. At the same time, the use of tiger products in traditional Chinese medicine and trade has perpetuated tiger hunting throughout history.

Despite the widespread distribution of HTCs, there has been a longstanding belief in the harmony between humans and nature, as well as the worship of the tiger. In certain regions and during specific periods, these beliefs have tempered HTCs and provided examples of human–tiger coexistence. Recently, the dissemination of scientific knowledge and the promotion of conservation principles have prompted the Chinese government to establish tiger conservation systems, create nature reserves and national parks to restore and protect tiger habitats, ban trade in tiger products, and promote human–tiger coexistence. As apex predators, tigers play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity in their ecosystems. Due to their small and dispersed populations, tigers are no longer a significant threat to local communities in China. The current focus is on restoring tiger habitats and promoting the recovery of tiger populations to ensure ecological balance and biodiversity in their ecosystems.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Zhihong Cao: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Yu Li: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Saud uz Zafar: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Yi Wang: Data curation; project administration; resources; writing—review and editing. Chuanping Nie: Conceptualization; data curation; resources; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge high gratitude to the chief editors and the reviewers for their professional advice and comments about the article. We would like to show gratitude to the Historical Animal Research Group 历史动物研究小组 from Shaanxi Normal University 陕西师范大学 for teamwork on data collection and academic discussion. Thanks also to Dr. Yu Xiaoyu 于潇雨 from Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG)西双版纳热带植物园 of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) for academic communication. Special thanks to Prof. Jiang Xuelong 蒋学龙, Li Xueyou李学友 (Kunming Institute of Zoology, CAS 中国科学院昆明动物研究所) and Wang Jingquan 王景荃 (Henan Museum 河南博物院) for providing some data and figures. Authors would like to extend gratitude to Ms. Zhai Yanhong 翟艳红 and Zhu Yufei 朱聿霏 for their sincere support for the article. The project is funded by The National Social Science Fund of China (No: 17FZS051).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Cao Zhihong). The data are not publicly available due to further research needs.