Local perceptions of anthropogenic and climate factors affecting the use and the conservation of Detarium microcarpum and Detarium senegalense in Burkina Faso (West Africa)

当地人对影响布基纳法索(西非)Detarium microcarpum(小果甘豆)和Detarium senegalense(甘豆)的使用和保护的人为因素和气候因素的看法

Editor-in-Chief: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz.

Handling Editor: Harald Schneider.

Abstract

enUnderstanding local perceptions and the different uses of multipurpose plant species is essential for their sustainable management. Despite this, anthropogenic factors such as deforestation, overexploitation of natural resources, extension of agricultural lands, overgrazing, and bushfires, coupled with the adverse effects of climate change, are contributing to the loss of these species. This study analyses the perceptions of local communities in Burkina Faso regarding the threats to Detarium microcarpum and Detarium senegalense and their implications, aiming to contribute to the effective management and conservation of such species. Through individual semi-structured and focus group interviews with 465 local people, data were collected on sociodemographic characteristics, plant parts used, use categories, threats and their effects, proposed solutions, and perceived conservation strategies. Descriptive statistics (consensus for plant part and relative frequency of citation), component analysis, and non-parametric analyses were used for data analysis. Results indicated that ethnicity, age, education level, and occupation were the most influential sociodemographic factors in relation to the use of these species. Six plant parts from both Detarium species are used across seven use categories, with fruits (0.40), trunks (0.16), and bark (0.27) being the most exploited. There was consensus among local populations regarding areas of abundance. Threat factors, their effects, and conservation solutions varied significantly according to site status. This study highlights the multipurpose uses of Detarium species throughout Burkina Faso and reveals that threats to these species are linked to the occupation and the status of each site. Sustainable use, effective conservation, and domestication of Detarium species should be considered to promote and sustain the exploitation of non-timber forest products.

摘要

zh了解当地人对多用途植物的认识与利用对这些植物的可持续管理至关重要。尽管如此,砍伐森林、过度开发自然资源、扩大农业用地、过度放牧和丛林火灾等人为因素,再加上气候变化的不利影响,正在导致这些物种的消失。本研究分析了布基纳法索当地社区对小果甘豆(Detarium microcarpum)和甘豆(Detarium senegalense)面临的威胁及其影响的认识,旨在为有效管理和保护此类物种做出贡献。通过对 465 名当地人进行个人半结构式访谈和集中小组访谈,收集了社会人口特征、植物利用部位、利用类型、威胁因子及其影响、建议的解决方案和认知保护策略认知等方面的数据。数据分析采用了描述性统计(植物部位共识和相对引用频率)、成分分析和非参数分析。结果表明,种族、年龄、教育水平和职业是对这些物种的使用最有影响的社会人口因素。2种甘豆属植物共有6个部位被用于七个用途类别,其中果实(0.40)、树干(0.16)和树皮(0.27)被利用最多。当地居民对主产区的认识是一致的,但是不同地区的威胁因素、人类的影响和保护方案有很大差异。这项研究强调了布基纳法索各地对甘豆属树种利用的多样性,并揭示了这些树种面临的威胁与每个原生地被占用情况和状态有关。为了促进和维持非木材森林产品(NTFPs)的开发利用,应考虑可持续利用、有效保护和驯化甘豆属物种。【审阅:朱仁斌】

Plain language summary

enUnderstanding rural populations' perceptions of the use and conservation of multipurpose species is crucial for effective and sustainable management of the resources these species provide. The valorisation and domestication of plant species require a scientific approach based on indigenous knowledge of their uses combined with conservation strategies. This study aims to contribute to the sustainable management of Detarium microcarpum and Detarium senegalense by analysing the perceptions of local populations regarding threats and potential solutions for their conservation. Data were gathered on informants’ sociodemographic characteristics, plant use categories, plant parts used and conservation issues. Descriptive statistics (consensus for plant part and relative frequency of citation), component analysis and nonparametric analyses were used for data analysis. Ethnicity, age, education level and main activity were sociodemographic factors that had the most influence on species use. Through the exploitation of nontimber forest products, Detarium species contribute to improving the livelihoods of rural populations. Local populations are aware of the decline and the disappearance of Detarium species in their surrounding habitats, potentially caused by increasing use and the effects of climate change. These species have high social value due to their diverse applications, including food, traditional medicine, construction and crafts, which utilise all parts of the plant. This study shows that threats to these species are linked to activities in the surrounding areas and to forest status. This research provides a foundation for scientifically informed insights into the potential risks these species face. Rural communities are aware of potential threats and have developed management strategies and solutions to ensure sustainable use practices.

简明语言摘要

zh了解农民对多用途植物利用与保护的认识,对于有效和可持续地管理这些物种资源至关重要。植物物种的价值评估和驯化需要一种基于本土知识的科学方法,并结合保护策略。本研究旨在通过分析当地居民对小果甘豆(Detarium microcarpum)和甘豆(Detarium senegalense)面临的威胁和潜在保护方案的认识,为可持续管理这两种植物做出贡献。收集的数据涉及信息提供者的社会人口特征、植物使用类别、使用的植物部分以及保护问题。数据分析采用了描述性统计(植物部位共识和相对引用频率)、成分分析和非参数分析。种族、年龄、教育水平和主要活动是对物种使用影响最大的社会人口因素。通过开发非物质文化遗产,甘豆属树种有助于改善农村人口的生计。当地居民意识到,由于使用量的增加和气候变化的影响,周围栖息地中的甘豆属物种正在减少和消失。这些物种具有很高的社会价值,因为它们有多种用途,包括食品、传统医药、建筑和手工艺品,这些用途利用了植物的各个部分。这项研究表明,这些物种面临的威胁与周边地区的活动和森林状况有关。这项研究为从科学角度深入了解这些物种面临的潜在风险奠定了基础。农村社区已经意识到潜在威胁,制定了管理策略和解决方案确保可持续利用。

Practitioner points

en

-

Local populations are aware of the decline and disappearance of Detarium species in their habitats, attributing this trend to excessive human exploitation and the effects of climate change.

-

The challenges faced by Detarium species are correlated with activities in the surrounding area and individual forest status. Detarium plant resources may face challenges in forests with different levels of protection status due to habitat fragmentation and the effects of climate change.

-

Rural communities have devised strategies and solutions which can contribute to the conservation of Detarium species.

实践者要点

zh

-

当地居民意识到在他们的栖息地中,甘豆属(Detarium)正在减少和消失,这一趋势由人类的过度开发和气候变化的影响导致。

-

甘豆属(Detarium)面临的挑战与周边地区的活动和个别森林的状况有关。生境破碎化和气候变化的使得甘豆属植物资源可能在不同保护级别的森林中面临挑战。

-

农村社区已制定保护甘豆属(Detarium)的战略和解决方案。

1 INTRODUCTION

Climate change constitutes a critical environmental factor that significantly impacts natural habitats, compromising the development of African countries with limited and fragile resources (Liu et al., 2022). This situation adversely affects the livelihoods of most rural populations, which rely on natural resources such as nontimber forest products (NTFPs). Forests serve as biodiversity reservoirs, playing a vital role in providing ecosystem services to local communities (Agbo et al., 2017). These services, which humans derive from ecosystems in various ways (Leßmeister et al., 2018), contribute to rural communities' resilience against the effects of climate change (Gning et al., 2013). Mensah et al. (2014) reported that increasing human populations have led to intensified forest degradation due to the rising demand for forest products. Tan (2022) also found that the world's ecosystems are changing more rapidly with global population growth. Human actions such as deforestation, overexploitation of natural resources, agriculture, overgrazing and bushfires, coupled with the adverse effects of climate change, contribute to the loss of many multipurpose species. This loss affects natural ecosystems, diminishing their ability to provide goods and services to West African communities (Fontodji et al., 2019). The irreversible loss of plant species biodiversity leads to ecosystem degradation, impacting both ecosystem services and human well-being (Sintayehu, 2018).

The decline of multipurpose species in Sub-Sahara Africa greatly impacts communities and societal groups most dependent on forest resources (IPCC-IPBES, 2020). Maja and Ayano (2021) explain that population growth, urbanisation and economic development have exacerbated food insecurity, increasing pressure on multipurpose woody species. Detarium microcarpum Guill. & Perr. and Detarium senegalense J.F. Gmel. are among the most exploited species in Burkina Faso (Bationo et al., 2001), Benin (Agbo et al., 2019) and Mali (Kouyaté, 2005). These species face vulnerabilities in their occurrence areas, yet their conservation status remains unclassified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Lamy Lamy et al., 2021).

In recent years, much research effort has focused on the socioeconomic contributions (Kouyaté et al., 2002; Florence et al., 2014) and regeneration concerns (Agbo et al., 2019; Bationo et al., 2001; Lamy Lamy et al., 2021; Ricez, 2008) of D. microcarpum and D. senegalense. While several studies have shown the importance of Detarium species in food and economic sectors through the exploitation of NTFPs, less attention has been given to local perceptions of the threats to these species. The exploitation of plant parts from species such as D. microcarpum and D. senegalense serves as a resilience strategy through the ecosystem services provision for rural populations. With increasing populations, NTFP market values have risen, putting greater pressure on these woody multipurpose species. This pressure contributes to the vulnerability of D. microcarpum and D. senegalense (Ouédraogo et al., 2021; Yaovi et al., 2021). In addition, the lack of effective management strategies and insecurity in West African Sahelian countries amplify the threats to these species (Zerbo et al., 2022). Understanding local communities' resilience, alongside their perceptions of climate effects and current threats to Detarium species, is essential for assessing their adaption potential (Houndonougbo et al., 2020; Ouko et al., 2018; Tiétiambou et al., 2015).

Given the significant role of Detarium species in Burkina Faso (Bationo et al., 2001; Maré & Millogo, 2019), it is necessary to investigate local perceptions regarding the degradation of these plant resources in the current context of climate change and overexploitation. Knowledge of human perceptions towards plant species is a key factor in understanding ecosystem dynamics for sustainable biodiversity management. Moreover, the valorisation and the domestication of plant species require a scientific approach that incorporates indigenous knowledge of their uses into conservation strategies (Balima et al., 2018). In Burkina Faso, several studies have been carried out on the sociocultural, economic and ecological significance of multipurpose woody species such as Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Kouyaté et al., 2002), Afzelia africana Sm. ex Pers. (Balima et al., 2018) and Bombax costatum Pellegr. & Vuillet (Zerbo et al., 2022). While previous ethnobotanical studies on Detarium species have been carried out across West Africa in countries like Benin (Agbo et al., 2017), Togo (Dangbo et al., 2019), Senegal (Diop et al., 2010), Mali (Kouyaté et al., 2002) and Burkina Faso (Bationo et al., 2001), many aspects remain unexplored. This study aims to fill some of these gaps by analysing local population perceptions regarding the threats to D. microcarpum and D. senegalense, and their implications for management. Specifically, it aims to (i) identify the specific parts of these species that are exploited, (ii) assess the impact of sociodemographic characteristics on their use, (iii) analyse the local perceptions of species decline and (iv) assess local conservation strategies to ensure their sustainable use in Burkina Faso.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

2.1.1 Study area

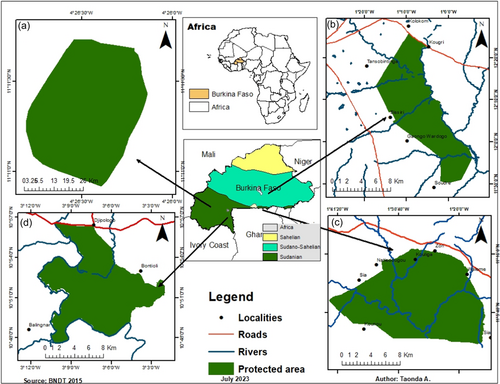

The study was conducted along a climatic gradient in Burkina Faso, a country in West Africa, located between the latitudes 09°02′–15°05′N and the longitudes 05°03′W 02°02′E. With a total area of 274,400 km2, the population is estimated at 20,487,979 habitants, resulting in a density of 51.08 inhabitants/km2 (INSD, 2020) (Figure 1). The research focused on villages surrounding four protected areas (PAs) known to harbour natural populations of Detarium species. These areas include the Classified Forest of Nakambe (located in the Sudano-Sahelian climatic zone), the Classified Forest and Game Ranch of Nazinga (located in the transition zone between the Sudanian and Sudano-Sahelian climatic zones), the Wildlife Reserve of Bontioli and the Classified Forest of Kou (both located in the Sudanian climatic zone). These classified forests were selected based on their accessibility stemming from the current security challenges the country is facing.

The main ethnic groups residing around the PAs in the study region are diverse: Mossi near the Classified Forest of Nakambe, Gourounsi around the Classified Forest and Game Ranch of Nazinga, Dagara around the Wildlife Reserve of Bontioli and Bobo around the Classified Forest of Kou. Predominantly, these communities engage in agriculture, relying on the cultivation of millet, Azia maise and sorghum, alongside herding and provisioning ecosystem services from trees (Dimobe et al., 2015).

According to National Meteorological Office data, the Sudano-Sahelian zone experiences annual rainfall ranging from 600 to 900 mm spread over 4–5 months, with average temperatures around 30°C. The Sudanian zone receives an annual rainfall of 900–1200 mm over a longer rainy season lasting 5–6 months, with a cooler average annual temperature of 26°C. The vegetation in the four PAs is characterised by various vegetation types, including shrub savannas, tree savannas, woodlands, dry forests and gallery forests (Nacoulma et al., 2018).

2.1.2 Study species

D. microcarpum and D. senegalense are woody species belonging to the Fabaceae family (Arbonnier, 2009). D. microcarpum, a medium-sized tree, can reach up to 12 m in height and is distinguished by its dense spherical crown (Maré & Millogo, 2019; Thiombiano et al., 2012). D. senegalense is larger, usually growing to between 15 and 30 m, and even reaching 40 m within forest galleries (Houénon et al., 2021). The two species differ in several morphological aspects: D. microcarpum typically has fewer, larger and tougher leaflets, more compact inflorescences, externally hairy sepals and slightly smaller fruits compared to D. senegalense (Dangbo et al., 2019; Diop, 2013; Dossa, Gouwakinnou, et al., 2020). Both species feature paripinnate leaves with 5–6 pairs of opposite leaflets arranged alternately. The leaflets are 4–6 cm long and 3–4 cm wide, oval to elliptical, rounded at the ends and emarginate at the top. The limb is thin, flexible, finely leathery, pinnate and green on the underside. Their inflorescence form in axillary panicles and measure between 5 and 8 cm in length. The creamy white flowers, in raceme, have a glabrous or glabrescent calyx. They have four elliptical sepals with an ovoid and pubescent ovary, supported by 10 white bilocular stamens. These species are mainly dispersed by animals and exhibit distinct habitats (Bationo et al., 2001; Kamou et al., 2017).

D. microcarpum thrives in dry savannas, dry forests and fallow lands on sandy or iron-rich hard soils (Houénon et al., 2021; Kouyaté et al., 2006). Detarium senegalese prefers dry lowland forests, gallery forests in savannah areas (Cavin, 2007; Diop et al., 2010) and humid forests (Sanusi, 2022). Notably, certain Detarium species, like D. microcarpum, have shown some resistance to fire (Diatta et al., 2021). Propagation of these species can occur both vegetatively and from seeds (Bationo et al., 2001; Ricez, 2008).

2.2 Method

2.2.1 Sampling

A total of 465 individuals were interviewed using a simple random sampling technique, without gender considerations, based on their knowledge of plant parts of the two species in question (Zerbo et al., 2022). The number of interviewees varied from 65 to 185 individuals across different sites, determined by the population density of each area. Participants included local residents of various ages, with a minimum age requirement of 30 years to ensure respondents had sufficient experience to identify changes in climate and anthropogenic threats to the species. Before conducting interviews, administrative and traditional leaders, as well as youth leaders at each site, were informed to aid in establishing a conducive environment for interactions with community members.

2.2.2 Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions from September to December 2022 (Balima et al., 2018; Naah & Guuroh, 2017; Zerbo et al., 2022). To ensure accurate identification, specimens of the Detarium species were provided to informants at each site. Interviews were conducted in local languages and translated by site-specific translators. Informants provided verbal consent before participation. The questionnaire included a combination of closed and open-ended questions and was designed to gather data on sociodemographic characteristics (ethnicity, sex, age, education level and occupation) and the uses of different plant parts from the targeted species (Zerbo et al., 2022). Additional questions related to areas of abundance, threats and their impacts on the species and conservation solutions for sustainable resource management were also included. Informants provided insights into the current status of the species, including stability, decline or disappearance and motivations for their conservation.

2.2.3 Data analyses

To determine the composition of the investigated population, the relative frequency of different sociodemographic characteristics, such as ethnic group, sex, age, education level and activity sectors, were computed. Regarding age consideration, the informants were grouped into three age categories following Assogbadjo et al. (2008): young (30 ≥ age < 45 years), adults (45 ≥ age < 60) and old (age ≥60 years).

To highlight which part of the species is used most often, the consensus value for plant part (CPP) was considered (Table 1). It measures the degree of agreement among informants concerning the plant part used (Monteiro et al., 2006). In addition, the relative frequency of citation (RFC) for use categories was calculated to identify the most common uses. The Kruskall–Wallis nonparametric test was used to assess whether CPP and RFC varied significantly according to the sociodemographic factors (ethnic groups, sex, age, education levels and activity sectors).

| No. | Parameters | Formula | Significations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Consensus value for plant part (CPP) | CPP = Px/Pt | Number of times a given plant part was cited (Px), divided by the total number of citations of all parts (Pt). Measures the degree of agreement among the informants concerning the plant part used (Monteiro et al., 2006). |

| 2 | Relative frequency of citation (RFC) | RFC = (S/N) × 100 | A measure calculated as RFC = (S/N), where ‘S’ represents the number of citations for a specific use of a plant part, and ‘N’ is the total number of informants. This metric provides insight into the relative importance of each plant part among the population for their provision of services. |

RFC was also used to evaluate local perceptions of presence areas, threats and conservation solutions for the sustainable use of the species. Bar plots were created to visualise the areas of presence using the tidyr package (Hadley et al., 2023). Correspondence analyses were performed to highlight the relationship between local population perceptions of threat factors and their consequences relative to different sociodemographic characteristics, using the packages factoMiner version 2.8 (Husson et al., 2023) and factoshiny (Vaissie et al., 2022).

Following Zerbo et al. (2022), RFC calculations for different ethnic groups were depicted using Sankey diagrams using the networkD3 package (Ellis et al., 2013).

All statistical analyses were performed with R software version 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2022).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the surveyed populations

The survey engaged 465 individuals across the study sites, of which 63.22% were men (Table 2). The age group 30–44 years was the most represented among respondents (56.56%). Mossi was the dominant ethnic group, comprising 38.49% of the total respondents and being the only group found at all sites. In terms of education, a significant proportion of the local population had no formal education (62.94%), followed by those with primary school education (27.31%). Occupationally, most of the respondents were farmers (43.44%) and household members (31.61%) (Table 2).

| Sociodemographic parameters | Sites | Total | Percentage (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bontioli | Kou | Nakambe | Nazinga | |||

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| Bobo | 0 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 13.55 |

| Dagara | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99 | 21.29 |

| Gourounsi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 60 | 12.90 |

| Mossi | 21 | 0 | 126 | 32 | 179 | 38.49 |

| Others | 0 | 2 | 59 | 3 | 64 | 13.76 |

| Total | 120 | 65 | 185 | 95 | 465 | 100 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 39 | 28 | 72 | 32 | 171 | 36.77 |

| Men | 81 | 37 | 113 | 63 | 294 | 63.23 |

| Total | 120 | 65 | 185 | 95 | 465 | 100 |

| Age | ||||||

| Young (30 > age ≤ 44 years) | 73 | 18 | 101 | 71 | 263 | 56.56 |

| Adult (45 > age ≤ 59 years) | 33 | 39 | 74 | 15 | 161 | 34.62 |

| Old (age >60 years) | 14 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 41 | 8.82 |

| Total | 120 | 65 | 185 | 95 | 465 | 100 |

| Education level | ||||||

| High primary | 10 | 2 | 10 | 27 | 49 | 10.54 |

| Illiterates | 88 | 46 | 107 | 48 | 289 | 62.15 |

| Primary level | 22 | 17 | 68 | 20 | 127 | 27.31 |

| Total | 120 | 65 | 185 | 95 | 465 | 100 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Farmers | 35 | 27 | 95 | 45 | 202 | 43.44 |

| Household | 30 | 25 | 60 | 32 | 147 | 31.61 |

| Official workers | 5 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 3.87 |

| Traditional mining exploitation | 33 | 33 | 7.10 | |||

| Traders | 10 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 43 | 9.25 |

| Traditional healer | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 2.58 |

| Wood exploitation | 10 | 10 | 2.15 | |||

| Total | 120 | 65 | 185 | 95 | 465 | 100 |

3.2 Use patterns of Detarium species according to sociodemographic characteristics

3.2.1 Impact of sociodemographic parameters on plant parts used

The survey identified six plant parts of Detarium species—fruits, bark, leaves, roots, branches and trunks—utilised by the local population for various purposes (Table 3).

| Sociodemographic factors | Bark | Fruits | Leaves | Roots | Branches | Trunks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Bobo | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.15 |

| Dagara | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.42 |

| Gourounsi | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Mossi | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| Others | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Mean | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| χ2 | 22.25 | 7.37 | 11.16 | 3.84 | 9.89 | 11.86 |

| p-Value | 0.0001 | 0.1177 | 0.0248 | 0.4278 | 0.0422 | 0.0184 |

| Education level | ||||||

| High Primary | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.25 |

| Primary | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.30 |

| Noneducated | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| Mean | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| χ2 | 6.01 | 3.20 | 4.53 | 3.91 | 2.47 | 2.05 |

| p-Value | 0.0497 | 0.2018 | 0.1039 | 0.1417 | 0.2906 | 0.3579 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.27 |

| Men | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| Mean | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| χ2 | 1.67 | 0.54 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 0.66 | 0.12 |

| p-Value | 0.1959 | 0.4621 | 0.9224 | 0.2729 | 0.4172 | 0.7276 |

| Age | ||||||

| Young | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Adults | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Old | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Mean | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| χ2 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 6.94 |

| p-Value | 0.5433 | 0.5433 | 0.6786 | 0.7454 | 0.5444 | 0.0312 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Farmers | 0.09 | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.49 |

| Traders | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.62 |

| Public workers | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| Household | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.38 |

| Traditional mining exploitation | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.54 |

| Wood exploitation | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.21 |

| Traditional healer | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.109 | 0.21 |

| Mean | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.54 |

| χ2 | 25.34 | 76.138 | 17.16 | 27.41 | 33.23 | 21.35 |

| p-Value | 0.00473 | 0.0000 | 0.071 | 0.0022 | 0.0002 | 0.0188 |

The CPP varied significantly according to the ethnic groups for bark (χ2 = 22.25; p = 0.0001), trunks (χ2 = 11.86; p = 0.0184), leaves (χ2 = 11.16; p = 0.0248) and branches (χ2 = 9.89; p = 0.0422), indicating distinct preferences and uses among different cultural backgrounds. However, this variation was not significant for fruits (χ2 = 7.38; p = 0.1177) or roots (χ2 = 3.84; p = 0.4278). Specifically, the Bobo group predominantly used leaves (CCP = 0.1384), while the Dagara group showed a higher usage of trunks (CPP = 0.41), followed closely by the Gourounsi (CPP = 0.33) and the Mossi (CPP = 0.30). Both Dagara (CPP = 0.10) and Gourounsi (CPP = 0.10) communities also exhibited notable use of roots.

The CPP among the surveyed populations did not significantly vary with education level (p > 0.05) for most plant parts, including fruits (χ2 = 3.20; p = 0.2018), leaves (χ2 = 4.53; p = 0.1039) roots (χ2 = 3.91; p = 0.1417), branches (χ2 = 2.47; p = 0.2906) and trunks (χ2 = 2.06; p = 0.3579), indicating a uniformity in the use of Detarium species across different educational backgrounds. However, a significant difference was observed for bark usage (χ2 = 6.01; p = 0.0497), suggesting that certain knowledge or preferences related to bark use might be influenced by education. Despite this, branches (CPP = 0.14) and trunks (CPP = 0.30) were primarily used by individuals with no formal education, perhaps reflecting traditional knowledge passed down through generations that do not rely on formal education systems. No significant differences were found in the CPP between genders (p > 0.05).

On the other hand, occupation significantly influenced the CPP (p < 0.05). Trunks (CPP = 0.54) and fruits (CPP = 0.42) were commonly used by people from all sectors. However, specific sectors showed unique preferences; for instance, public workers reported no use of roots, leaves, or branches (CPP = 0), possibly reflecting a disconnection from the traditional use of plants. Conversely, traditional healers (tradipraticiens) mostly used roots (CPP = 0.27), leaves (CPP = 0.23) and trunks (CPP = 0.20), suggesting a specific application in this sector. Interestingly, bark was most used by those in the traditional mining exploitation sector (CPP = 0.41) (Table 3).

3.2.2 Impact of sociodemographic parameters on use categories

The use of Detarium species parts spans various categories, including food, medicine, craft, energy, construction and sales (Table 4).

| Sociodemographic factors | Uses-categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Medicine | Craft | Energy | Seller | Construction | |

| Ethnics groups | ||||||

| Bobo | 18.55 | 27.34 | 12.97 | 22.56 | 17.35 | 1.25 |

| Dagara | 13.94 | 39.74 | 1.59 | 14.48 | 19.00 | 13.43 |

| Gourounsi | 20.46 | 25.07 | 13.08 | 18.23 | 19.26 | 3.92 |

| Mossi | 17.14 | 27.49 | 7.34 | 25.94 | 27.45 | 9.59 |

| Others | 18.97 | 25.03 | 8.27 | 21.25 | 22.40 | 2.08 |

| Mean | 17.81 | 28.94 | 8.66 | 20.49 | 21.09 | 6.05 |

| χ2 | 3.88 | 9.25 | 20.44 | 3.43 | 1.10 | 22.52 |

| p-Value | 0.4232 | 0.0552 | 0.0004 | 0.4882 | 0.8942 | 0.0002 |

| Age | ||||||

| Adults | 16.22 | 28.18 | 6.20 | 19.91 | 22.52 | 6.96 |

| Old | 15.52 | 33.80 | 9.20 | 20.51 | 10.98 | 9.99 |

| Youngs | 18.91 | 26.84 | 9.14 | 17.88 | 25.37 | 6.54 |

| Mean | 16.88 | 29.61 | 8.18 | 19.43 | 19.63 | 7.83 |

| χ2 | 1.95 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 1.31 | 6.93 | 6.93 |

| p-Value | 0.5827 | 0.9320 | 0.9136 | 0.7270 | 0.0743 | 0.6392 |

| Education level | ||||||

| High primary | 17.43 | 26.68 | 10.14 | 17.09 | 21.40 | 9.19 |

| Primary | 17.61 | 28.72 | 8.26 | 21.22 | 21.53 | 8.68 |

| Noneducated | 19.52 | 40.37 | 7.26 | 41.17 | 19.25 | 5.44 |

| Mean | 18.18 | 31.92 | 8.55 | 26.49 | 20.73 | 7.77 |

| χ2 | 0.03 | 22.03 | 0.03 | 18.08 | 0.24 | 0.74 |

| p-Value | 0.9860 | 0.0006 | 0.9835 | 0.0006 | 0.8863 | 0.6916 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 15.60 | 20.72 | 5.49 | 28.63 | 37.49 | 3.06 |

| Men | 19.05 | 34.20 | 10.16 | 20.07 | 6.77 | 10.36 |

| Mean | 17.33 | 27.46 | 7.82 | 24.34 | 22.13 | 6.71 |

| χ2 | 1.12 | 12.54 | 4.00 | 0.42 | 105.87 | 15.06 |

| p-Value | 0.2896 | 0.0004 | 0.0455 | 0.5181 | <2.2e−16 | 0.0001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Farmers | 38.48 | 78.52 | 45.06 | 69.26 | 32.80 | 40.88 |

| Public workers | 21.71 | 29.80 | 3.21 | 19.29 | 17.06 | 8.93 |

| Household | 27.89 | 21.88 | 4.31 | 21.03 | 29.45 | 4.44 |

| Traditional mining exploitation | 16.36 | 23.06 | 6.25 | 45.56 | 2.50 | 22.64 |

| Trader | 17.98 | 41.58 | 6.81 | 20.93 | 32.44 | 2.89 |

| Traditional healer | 7.25 | 56.06 | 7.97 | 9.68 | 17.60 | 1.45 |

| Wood exploitation | 15.14 | 31.09 | 14.46 | 11.43 | 23.79 | 4.09 |

| Mean | 20.69 | 40.28 | 12.58 | 28.17 | 22.23 | 12.19 |

| χ2 | 81.16 | 38.58 | 19.36 | 44.79 | 25.21 | 23.43 |

| p-Value | 0.0010 | 0.0001 | 0.0223 | 0.0001 | 0.0027 | 0.0053 |

The analysis of local population knowledge concerning the food use of Detarium species indicates a wide awareness across different sociodemographic groups, with no significant variation (p ≥ 0.05) among ethnic groups, age groups, education levels and gender. The activity sector presents a notable exception, where significant differences were observed (χ2 = 81.16, (p ≤ 0.05).

Gourounsi (RFC = 20.46%) and Bobo (RFC = 18.55%) ethnic groups emerged as the most knowledgeable in the use of the species for food. Similarly, younger (RFC = 18.91%) and adult age groups (RFC = 16.22%) knew more about food uses. Gender-wise, men (RFC = 19.05%) reported slightly more knowledge about food uses than women (RFC = 15.60%). Noneducated level respondents (RFC = 19.52%) reported higher use of Detarium species for food than other education levels. Farmers (RFC = 38.48%) and household members (RFC = 27.89%) reported more knowledge of food uses than those from other activity sectors.

In the medicinal use category, the analysis revealed that while knowledge does not significantly differ among ethnic groups and ages (p ≥ 0.05), it does vary with education level (χ2 = 22.02; p = 0.0006), gender (χ2 = 12.54; P = p ≤ 0.05) and activity sector (χ2 = 38.58, p = 0.0001). The Dagara (RFC = 39.74) ethnic group exhibited the highest frequency of citation of medicinal uses, followed by the Mossi (RFC = 27.49%) and Bobo groups (RFC = 27.33%). Older individuals (RFC = 33.79%), followed by adults (RFC = 28.18%), knew more about the medicinal uses of Detarium species. Regarding education level, the noneducated (RFC = 40.38%) and primary-level educated (RFC = 28.71%) individuals cited the species for medicinal use. Gender differences were evident, with men (RFC = 34.19%) reporting a higher familiarity with the species' medicinal applications than women (RFC = 20.72%). Occupationally, farmers (RFC = 78.52%) and traditional healers (56.06%) were the most knowledgeable about the species in the medicine category.

In the craft category, knowledge varied significantly according to ethnic group (χ2 = 20.44; p = 0.0004), gender (χ2 = 4.00; p = 0.0454) and occupation (χ2 = 19.37; p = 0.0222), but not across age groups and education levels (p ≥ 0.05). Farmers (RFC = 45.06%) had the highest RFC, highlighting their prominent use of the species in the craft category.

In the energy use category, knowledge of the use of Detarium species did not differ significantly by ethnic group, age, or gender (p ≥ 0.05). However, education level (χ2 = 18.08; p = 0.0006) and the occupation (χ2 = 44.79; p = 0.0001) had significant effects. The Mossi (RFC = 25.94%) and Bobo (RFC = 22.56%) ethnic groups made the most use of the species in the energy category. Older individuals (RFC = 20.51%) cited uses for energy more frequently than other age groups. Noneducated individuals (RFC = 41.17%) reported using the species for energy more than those with higher levels of education. Women (RFC = 28.63%) reported using these species for energy purposes more than men (RFC = 20.09%). Farmers (RFC = 69.27%) and those involved in traditional mining exploitation (RFC = 45.56%) indicated more knowledge about the use of Detarium species in the energy category.

The use of the Detarium species in the sales category differed significantly based on gender (χ2 = 105.87; p = <2.2e−16) and the occupation (χ2 = 25.21; p = 0.0027). Despite variations in educational background, age and ethnicity, participants shared similar knowledge (p ≥ 0.05). The Mossi ethnic group (RFC = 27.45%), followed by the other ethnic groups (RFC = 22.40%), sold more parts of the Detarium species. Younger individuals (RFC = 25.37%), adults (RFC = 22.52%), women (RFC = 37.49), farmers (RFC = 32.80%) and traders (RFC = 32.44%) were more knowledgeable about the commercial importance of the species.

In the construction use category, knowledge varied significantly between ethnic groups (χ2 = 20.44; p = 0.0004), genders (χ2 = 15.06; p = 0.0001) and occupation (χ2 = 23.44; p = 0.0053). However, educational level and age did not significantly affect knowledge in this area (p ≥ 0.05). The Dagara ethnic group (RFC = 13.43) and farmers (RFC = 40.88%) demonstrated the most knowledge about using the species for construction (Table 4).

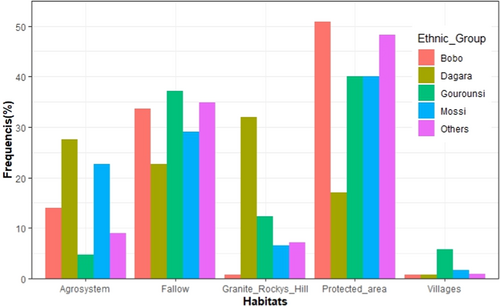

3.3 Local perceptions on the areas of abundance, threat factors and their effects on Detarium species conservation

The survey revealed five habitats identified by different ethnic groups as areas where Deatrium species are found (Figure 2). Except for the Dagaras ethnic group, which predominantly located the species on granite rocky hills (31.97%) and the agrosystem (27.50%), other groups reported higher abundance in PAs and fallows. The Bobo ethnic group observed the species most abundantly in the PAs (50.81%) and fallows (33.61%). Similarly, the Gourounsi group found the species mainly in the PAs (40.09%) and fallows (37.14%), while the Mossi group reported a significant presence in PAs (40.09%). Across all groups, villages were cited less frequently as habitats for these species, indicating a consensus on the species' rarity in village environments (Figure 2).

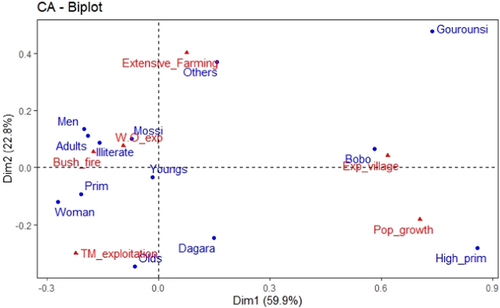

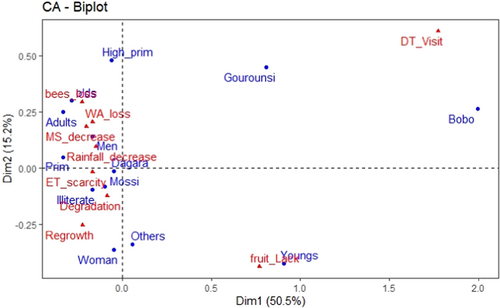

Local populations are aware that Detarium is under threat and have identified six factors that are impacting the survival of these species within their natural habitats. The correspondence analysis, which explains a significant 82.68% of the data distribution across two main axes, reveals how different sociodemographic groups perceive these threats (Figure 3). The first axis, accounting for 59.9% of the data distribution, correlates with the Mossi ethnic group, men, adults, youths, illiterate individuals and those with primary education levels. These groups perceived wood overexploitation and bushfires as the primary threats to Detarium species. The Bobo and Gourounsi ethnic groups mentioned village expansions as a significant threat, while members of the category ‘Other’ ethnic groups highlighted extensive farming as a primary concern. On the second axis, which explains 22.80% of the variation, there is a distinction between the Mossi ethnic group and their associated sociodemographic parameters against the backdrop of other ethnic groups. Here, the Dagara ethnic group, along with individuals who have high primary education levels and are older, associated traditional mining exploitation and population growth as significant threats (Figure 3).

Nine consequences associated with the threats to Detarium species were identified by the local populations (Figure 4), with their perceptions analysed through correspondence analysis, explaining 65.7% of the data distribution across two main axes. The first axis, which accounts for 50.50% of the data distribution, groups the Mossi, Dagara and ‘Others’ category ethnic groups alongside individuals who are illiterate or only have primary education, as well as adults. These groups share the same opinion that the effects of threats include regrowth and degradation of the species, a decrease in rainfall, a reduction in medicinal species decrease, loss of wild animals and a decline in bee populations'. On the second axis, explaining 15.2% of the variation, the Bobo and Gourounsi ethnic groups noted a decrease in tourist visits as a consequence of threats to the Detarium species (Figure 4).

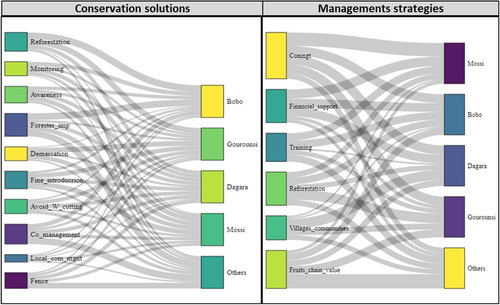

3.4 Local perceptions on conservation solutions and management strategies for Detarium species

Local populations proposed 10 solutions aimed at mitigating the decline of Detarium species, with significant variation in preferences among different ethnic groups (χ2 = 696.76; p < 0.0001) (Figure 5). The Mossi ethnic group suggested the importance of demarcation (44%) and comanagement (36%) as critical measures for preventing species decline. The Gourounsi highlighted the need for awareness (21.43%) and monitoring of the species (23.19%). The Bobo expressed a preference for comanagement (27.69%) and the introduction of fines (22.45%) (Figure 5).

For the sustainable management of Detarium species, six conservation strategies were mentioned (Figure 5), with preferences varying significantly among ethnic groups (χ2 = 696.76; p < 0.0001). The strategies of comanagement (53.29%), financial support (48.79%) and valorisation of the fruit value chain (47.38%) were the most requested. The Mossi suggested comanagement (43.41%), financial support (37.23) and reforestation (23.37%), while the Gourounsi preferred reforestation (43.28%), comanagement (41.32%) and fruit value chain valorisation (35.67%). The Dagara ethnic group mentioned local community management (36.21%), comanagement (31.62%) and financial support. Members of the ‘Others’ ethnic group category requested valorisation of the fruit value chain and training.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Variations in Detarium species use

This study showed that D. microcarpum and D. senegalense are species with multiple uses, with local communities exploiting nearly every part of these plants—roots, bark, trunk, fruit, leaves and branches—for a variety of purposes. This extensive use underscores the significant value of Detarium species as multipurpose resources for the local population (Gaisberger et al., 2017). The broad spectrum of applications for these species confirms their importance in supporting rural livelihoods (Houénon et al., 2021; Sreekumar et al., 2020). Dimobe et al. (2018) identified Detarium species among the priority multipurpose species in Burkina Faso, a designation also accorded to other species like A. africa (Balima et al., 2018) and B. costatum (Zerbo et al., 2022).

Informants mostly mentioned the use of fruits and trunks of the Detarium species. This high fruit usage indicates that the species play a role in food security, contributing to the resilience of rural populations. Similarly, the extensive use of trunks indicates the dependency on these species for timber (Sinadouwirou et al., 2022).

The study also revealed that sociodemographic factors influence the exploitation patterns of Detarium species. Women's focus on trunks and branches underlines the use of the species as firewood and is indicative of their role in gathering firewood, a task integral to cooking responsibilities within households. This pattern aligns with observations made by Kouyaté (2005) in Mali and Agbo et al. (2020) in Benin, highlighting this gendered knowledge and use of firewood trees. This particular interest in trunks poses a considerable challenge to the conservation of the species (Biara et al., 2021), as it directly impacts the availability of mature trees. Harvesting leaves, fruits and bark could also potentially affect the reproductive performance of the species, further stressing the need for sustainable management practices (Nacoulma et al., 2017).

The distinct CPPs reported by individuals with higher levels of education, compared to the lower values associated with branches and trunks, suggests that the level of education influences choices regarding energy sources. Gkargkavouzi et al. (2020) illustrated that a higher education level is often correlated with a positive stance towards species conservation, implying that education plays a crucial role in promoting conservation efforts. However, the impact of modernisation and development seems to be affecting traditional knowledge systems concerning the use of multipurpose species in the region. Monteiro et al. (2006) explained how progress in modernisation has influenced the dynamics of plant use, potentially diminishing the transmission and application of indigenous knowledge concerning these species.

The pronounced preference for fruit among traders and farmers, as indicated by the high CPP values, underscores the dual role of Detarium species as both a nutritional supplement for farmers and a source of income. This observation aligns with Lykke et al. (2004), who showed that the importance attached to a species often depends on its utility to different user groups. Furthermore, Monteiro et al. (2006) and Zerbo et al. (2022) observed that preferences for specific plant parts differ among communities, highlighting the diverse ways in which multipurpose species support the resilience and food security of rural communities. The importance of such species in the livelihoods of rural populations is further supported by studies from Kuhlman et al. (2010), Guigma et al. (2012) and Balima et al. (2018).

The broad involvement of the different parts of Detarium species across six categories of use highlights their importance to the local population. This study found that gender, age and occupation influence knowledge about the species' uses, in line with results reported by Monteiro et al. (2006). The exploitation of different parts was strongly linked to occupation and education levels. Notably, fruit sales are dominated by young people and women, highlighting their active participation in utilising these species for economic benefits. Younger individuals, full of energy and driven by the pursuit of wealth, show a keen interest in collecting the fruit of these species (Biara et al., 2021). Kristensen and Balslev (2003) suggest that sociocultural and demographic factors such as gender, age and education level correlate with the knowledge and use of plant parts. Ahenkan and Boon (2011) show women's essential role in the commercialisation of NTFPs in West Africa, contributing to rural community resilience by opening new economic opportunities. Malleson et al. (2014) demonstrated that NTFPs offer new income sources for many women in the rural areas of Cameroon and Nigeria.

The high frequency of use reported by women in the energy category (firewood) underlines the species' value to households, likely due to the wood's flame intensity and low smoke emission (Ramos et al., 2008; Sinadouwirou et al., 2022). Other studies like Dao et al. (2020) and Sinadouwirou et al. (2022) have also emphasised wood characteristics as a primary factor in firewood selection. Moreover, another study pointed out the dependence of local populations on forest resources for various needs and income generation, exacerbating deforestation and forest degradation (Hesselberga & Iversenb, 2011).

Ethnic- and age-related preferences were observed, with the Mossi using the species for firewood and the younger population engaging in fruit selling, indicating usage variations based on ethnic group and age. Diatta et al. (2021) mentioned that D. microcarpum and D. senegalense were at the heart of local income activities in Thiobon, Senegal. Their use in traditional medicine constitutes a significant degradation factor (David et al., 2017). This medicinal importance can be attributed to antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antimalarial effects, as well as nutritional components (Dieng et al., 2016; Kini et al., 2010). Dogara (2022) found that each part of the D. microcarpum plant has a therapeutic application and the plant is often referred to as a miracle plant by traditional herbalists. In addition, the widespread use of bark and roots in traditional medicine illustrates the species' therapeutic significance, aligning with global reliance on traditional medicine as a source of primary health care (Houénon et al., 2021).

The use of the Detarium species for crafts and construction reflects their wood quality, which Sawadogo (2007) identified as a factor contributing to their vulnerability. Members of the Dagara ethnic group mentioned that cultural practices, such as rituals conducted by traditional healers, also influence the use of these species. The extensive use of bark, branches, roots and fruits found in this study poses a great threat to their sustainability, with rural communities heavily relying on multipurpose species such as Detarium for income, particularly women and young people involved in fruit picking and selling (Kagambega, 2019).

4.2 Local perceptions of areas of abundance, threat factors and threat effects of Detarium species

This study shows that Detarium species are highly valued by local populations, underscoring their critical role within areas of natural occurrence. The consensus among local populations indicates that PAs and fallows are key zones of abundance, affirming the significance of these areas for species conservation (Assogbadjo et al., 2012). This is in accordance with FAO (2015) findings that highlight a positive relationship between species abundance and the level of habitat protection. The species' presence on hills and granite rocks corroborates previous studies indicating a preference for granitic soils (Aubréville & Trochain, 1937; Diop et al., 2010; Dossa, Ouinsavi, et al., 2020).

In contrast, the diminished presence of Detarium species in villages underscores the adverse impact of unregulated exploitation and habitat degradation in non-PAs. This observation is consistent with Agbo et al. (2017) and other studies, which highlight the complex interplay between species protection, uses, proximity and cultural practices (Avakoudjo et al., 2020; Coulibaly et al., 2021; Dogara, 2022). These findings suggest an urgent need for the domestication of Detarium species to mitigate the risks associated with their overexploitation and to promote sustainable use (Kouyaté et al., 2002; Sinadouwirou et al., 2022).

The study revealed that local populations are aware of the decline and the disappearance of Detarium species from their habitat, primarily attributed to the overexploitation of plant parts, such as the bark and the trunk, alongside habitat destruction for agricultural expansion. This indiscriminate exploitation across all plant parts significantly jeopardises the species' survival (Yaovi et al., 2021). The major threats identified in Burkina Faso include bushfires, population growth, wood overexploitation and traditional mining exploitation. López-Carr (2021) shows the impact of urban development related to population growth on species dynamics, while Gaisberger et al. (2017) explain that overexploitation is due to the vulnerability of local populations. Extensive farming is one of the most common causes of forest exploitation, with illegal logging for firewood contributing to the species' scarcity. Traditional mining exploitation, particularly at the Bontioli site, further exacerbates these threats. Consequently, the combined effect of these pressures constitutes a major challenge to the sustainable management of Detarium species, underlining the need for effective conservation strategies to mitigate the ongoing risks to their survival, as noted by Avakoudjo et al. (2020).

In addition to the anthropogenic factors mentioned, local populations pointed out that climate change contributes to the vulnerability of Detarium species (Agossou et al., 2012). Communities residing near PAs perceive climate events like drought, high winds and rising temperature as threat factors which impact Detarium species populations. Nunes et al. (2019) and Deb et al. (2021) support this observation, indicating that local populations are often the first to notice the effects of climate change and forest degradation. Gross-Camp et al. (2015) and Dey et al. (2017) pointed out that the experiential knowledge of local communities, shaped by their livelihoods and direct interactions with their environment, plays a crucial role in recognising and understanding these impacts.

Furthermore, the decline in fruit availability is attributed to illegal logging, targeting mature Detarium trees and climatic hazards. These events not only lead to a decrease in the number of adult trees capable of fruit production but also affect the overall health and reproductive capacity of the species (Kamou et al., 2017; Kagambega, 2019; Fontodji et al., 2019).

4.3 Local people's perceptions on conservation strategies and valorisation of Detarium species

For the sustainable conservation of Detarium species, awareness, local community management and comanagement with the foresters have been emphasised by local populations. These approaches underscore the vital role local stakeholders play in the sustainable use of ecosystem goods and services of woody species (Badjaré et al., 2018). However, the diversity of solutions proposed, influenced by occupations, showed the integral part forests play in supplementing community livelihoods. Local communities advocate for awareness, monitoring to protect against overexploitation and the introduction of alternative species like almonds, which can help combat overexploitation and the illegal exploitation of forest resources. Engaging local communities in species management enhances security through sustainable participatory management (Delvingt & Doucet, 2000; FAO, 2013, 2015), offering a unique opportunity to educate them on natural resource depletion and ecosystem service provision (Gning et al., 2013).

Site status influences management type, with suggestions including wood-cutting regulations, the promotion of more effective stoves and alternative village energy solutions. To reduce the rate of species decline, local populations propose multiple conservation strategies to ensure sustainable use, such as financial support, product valorisation, training capacity building and reforestation. This initiative proves that the sustainable management of indigenous species contributes to improving the livelihoods of rural communities. However, community contribution to forest management is highly variable and often dependent on their main occupation (Lawin et al., 2019; Mugisho et al., 2022). While some communities have a high degree of knowledge concerning species management, others require basic training specifically tailored to align with local knowledge and practices. Kristensen and Balslev (2003) explain that the local communities' opinion is the guideline to ensure the best management of the natural resources. Despite the species not receiving much attention, species managers are taking steps to enhance the sustainable management of certain versatile species, including Detarium productivity (Bowler et al., 2012; Jones & Lynch, 2007; Wouyo et al., 2014). Income diversification, especially for women and youths involved in the collection, is key to forest protection, as illustrated by studies from Tiétiambou et al. (2015) and Hounsou-Dindin et al. (2022). The development of effective management strategies that consider the opinions and needs of local communities is essential. The valorisation of Detarium fruit, particularly by women, could integrate them into the value chain, boosting their incomes. The success of these initiatives requires collaboration among all stakeholders, including policymakers, local communities, researchers, extension agencies and funding bodies.

5 CONCLUSION

This study showed the significant influence sociodemographic factors have on the uses of D. microcarpum and D. senegalense, demonstrating the rural population's awareness of the decline of these species within their environment. Detarium species have high social value, especially in use categories such as food, traditional medicine, construction and crafts, with all plant parts being exploited, reflecting their diverse application. Among the ethnic groups studied, the Mossi showed the most extensive knowledge of the utilisation of plant parts and application forms for D. microcarpum, with the Bobo similarly knowledgeable about D. senegalense.

This study underscored the negative consequences of species overexploitation on their survival, revealing that threats to these species are closely linked to site-specific activities and the status of individual forests. Moreover, rural communities demonstrated awareness of these threats, proposing certain solutions and management strategies to address them. This study also aims to provide a scientific foundation for a better understanding of the challenges facing these species. For effective conservation of the two Detarium species, it is imperative that environmental authorities, NTFP associations and nongovernmental organisations involved in plant conservation initiate training programmes and diversify the economic income of local populations through financial support. Such measures are essential for mitigating the impacts of overexploitation and ensuring the sustainable management of D. microcarpum and D. senegalense.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Adama Taonda conceived the work with advice from Issouf Zerbo, Anny Estelle N'guessan, Justin N'Dja Kassi and Adjima Thiombiano. Adama Taonda collected and Issouf Zerbo curated the data. Issouf ZERBO performed a formal analysis. Adama Taonda and Issouf Zerbo drafted the manuscript with the contribution of Anny Estelle N'guessan, Justin N'Dja Kassi and Adjima Thiombiano. All authors validated the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our sincere appreciation goes to the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the West African Science Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use (WASCAL) for providing the scholarship and financial support for this program. The authors are grateful to local authorities and the population who accepted the realisation of the study in their localities. The authors are also grateful to local people for accepting to share their perception of Detarium microcarpum and Detaium senegalense (Kou). This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (WASCAL_GRP/CCB4).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All local people involved in this research consented to the use of their information during data collection, in compliance with ethical and legal standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available if the request need after the publication. Data in WASCAL are open access and are made available upon the receipt of an official request to the institution through the Data Management Department and the corresponding author ([email protected]).