Cost-effective molecular inversion probe-based ABCA4 sequencing reveals deep-intronic variants in Stargardt disease

Abstract

Purpose

Stargardt disease (STGD1) is caused by biallelic mutations in ABCA4, but many patients are genetically unsolved due to insensitive mutation-scanning methods. We aimed to develop a cost-effective sequencing method for ABCA4 exons and regions carrying known causal deep-intronic variants.

Methods

Fifty exons and 12 regions containing 14 deep-intronic variants of ABCA4 were sequenced using double-tiled single molecule Molecular Inversion Probe (smMIP)-based next-generation sequencing. DNAs of 16 STGD1 cases carrying 29 ABCA4 alleles and of four healthy persons were sequenced using 483 smMIPs. Thereafter, DNAs of 411 STGD1 cases with one or no ABCA4 variant were sequenced. The effect of novel noncoding variants on splicing was analyzed using in vitro splice assays.

Results

Thirty-four ABCA4 variants previously identified in 16 STGD1 cases were reliably identified. In 155/411 probands (38%), two causal variants were identified. We identified 11 deep-intronic variants present in 62 alleles. Two known and two new noncanonical splice site variants showed splice defects, and one novel deep-intronic variant (c.4539+2065C>G) resulted in a 170-nt mRNA pseudoexon insertion (p.[Arg1514Lysfs*35,=]).

Conclusions

smMIPs-based sequence analysis of coding and selected noncoding regions of ABCA4 enabled cost-effective mutation detection in STGD1 cases in previously unsolved cases.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although Sanger sequencing is considered the gold standard for the identification of disease-associated variants, it is less suitable for the identification of variants in one or more genes consisting of many exons due to high costs and low throughput (Neveling, den Hollander, Cremers, & Collin, 2013). The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the genotyping of patients with inherited diseases, including inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) (Carss et al., 2017; Levy & Myers, 2016). Whole exome sequencing (WES) is a cost-effective method that reveals the large majority of coding and splice site variants but cannot detect deep-intronic and regulatory variants. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) in principle detects all variants, including structural variations, but disadvantages are extensive data processing time and storage of a huge amount of data. As an alternative, NGS-based targeted sequencing approaches have been introduced to selectively enrich and sequence the genomic regions of interest. Advantages include better coverage and faster generation of data (Lin et al., 2012).

One of the target enrichment strategies is based on molecular inversion probes (MIPs). Single-molecule (sm)MIPs contain a unique tag. Due to their dual annealing properties, smMIPs and MIPs are very specific and have been used in multiplex PCR enrichment consisting of 1,312 or 6,200 probes to analyze 33 genes involved in cancer (Hiatt, Pritchard, Salipante, O'Roak, & Shendure, 2013) or 108 genes implicated in IRDs (Weisschuh et al., 2018), respectively. This technology requires an initial investment in synthesizing smMIP oligonucleotides and balancing of their targeting properties, but thereafter it is superior in terms of cost, throughput, scalability, sensitivity and specificity. smMIPs can be used for simultaneous sequencing of hundreds of patients (Neveling et al., 2017; Weisschuh et al., 2018).

In this study, we aimed to identify mutations in patients with Stargardt disease (STGD1). STGD1 (MIM# 248200) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding the ATP binding cassette type A4 (ABCA4; MIM# 601691; Allikmets et al., 1997). With an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000 individuals (Blacharski et al., 1988), STGD1 is the most frequent juvenile inherited macular dystrophy and ABCA4 is the most frequently mutated IRD-associated gene (Hussain et al., 2018; Tanna, Strauss, Fujinami, & Michaelides, 2017). In an inventory of all reported variants and cases, 5,962 (allelic) variants identified in 3,928 cases were listed (Cornelis et al., 2017). Until recently, 35% of STGD1 cases carried one or no coding or splice site mutation (Zernant et al., 2014). Copy-number variations (CNVs), deep-intronic variants (Bauwens et al., 2015; Bax et al., 2015; Braun et al., 2013; Zernant et al., 2014), and a low-penetrant frequent coding variant (p.Asn1868Ile) (Runhart et al., 2018; Zernant et al., 2017) explained about 10% of this missing heritability. Recently, upon sequence analysis of the entire ABCA4 gene, eight novel and one known deep-intronic variant explained approximately 65% of the remaining unsolved cases (Bauwens et al., 2019; Sangermano et al., 2019; Zernant et al., 2018). As the phenotype is specific and no other gene has been described to be mutated in typical STGD1 cases since ABCA4 was identified 22 years ago (Allikmets et al., 1997), hundreds of cases have remained genetically unsolved due to the low-sensitive mutation scanning techniques that were used such as single strand conformation polymorphism (Klevering et al., 2004; Maugeri et al., 1999), denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (Maia-Lopes et al., 2009), and arrayed primer extension (Jaakson et al., 2003).

In this study, we aimed to develop a cost-effective sequencing method for the complete ABCA4 gene based on smMIPs. As a first step, we developed smMIPs to sequence all 50 exons and flanking splice sites, as well as selected regions carrying 14 known causal deep-intronic variants. Using this smMIPs platform, we sequenced 411 genetically unsolved STGD1 cases. Selected novel noncanonical splice site (NCSS) and deep-intronic variants were tested by using midigene splice assays.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study cohort

We analyzed the ABCA4 gene for sequence variants employing STGD1 cases from Lille, France (n = 223 cases) and Regensburg, Germany (n = 188 cases). Samples were collected according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. STGD1 samples from the French cohort (originating from a cohort of 1,133 probands) were prescreened using the following techniques: high resolution melting (HRM) mutation detection analysis, denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC), or NGS of four IRD-associated genes, including ABCA4. The STGD1 cases from Germany (originating from a cohort of 335 probands) were previously sequenced using a custom-designed GeneChip CustomSeq Resequencing Array (RetChip; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA; Schulz et al., 2017) or NGS on an ION Torrent semiconductor personal sequencing machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) upon multiplex-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the fragments with the STARGARDT MASTR Kit (Multiplicom, Niel, Belgium).

2.2 Design of smMIPs

The design of smMIPs was performed in two series. First, smMIPs were designed to sequence the 50 protein-coding exons of ABCA4 (NM_000350.2), including at least 20 base pair (bp) upstream and 20 bp downstream sequences encompassing the splice site consensus sequences. Also six previously reported deep-intronic variants including (c.4253+43G>A, c.5196+1137G>A, c.5196+1216C>A, c.5196+1056A>G, c.4539+2001G>A, c.4539+2028C>T) (Braun et al., 2013; Zernant et al., 2018) were captured covering small parts of introns 30 (182 bp) and 36 (226 bp). In the first sequence analysis of 22 test DNA samples, smMIPs targeting exons 7, 10, 13, 31, 33, 36, 37, 38 and 46 resulted in less than 10 reads whereas the average coverage of all smMIPs was >40 reads. To cover these gaps, 23 additional smMIPs were designed and added in the second sequence analysis to improve the coverage of these regions. All regions were covered well except for the last three nucleotides of exon 10 and the first 20 nucleotides of intron 10. Thereafter, the final rebalanced smMIP pool consisted of 309 smMIPs including 299 exonic and 10 intronic smMIPs.

In addition, eight recently discovered causal deep-intronic variants (c.769–784C>T, c.859–506G>C, c.859–540C>G, c.1937+435C>G, c.4539+1100A>G, c.4539+1106C>T, c.4539+2064C>T and c.5197–557G>T) (Bauwens et al., 2019; Sangermano et al., 2019) as well as 300 bp upstream and 300 bp downstream sequences were captured using 174 smMIPs (Table S1 and Figure S1). Larger segments were sequenced as they may carry novel causal deep-intronic variants that may affect the recognition of the same pseudoexons by the splicing machinery. Thereafter both pools were combined and consisted of 483 smMIPs.

To design smMIPs, the genomic positions were obtained from the UCSC genome browser (hg19; https://genome.ucsc.edu). smMIPs were designed using MIPgen pipeline (Boyle, O'Roak, Martin, Kumar, & Shendure, 2014). For each target region overlapping smMIPs were designed in a double-tiling fashion, that is, one on the plus strand and one on the minus strand. Details of the smMIPs and their distribution across ABCA4 are provided in Table S1 and Figure S1.

Each smMIP is 78 nucleotides long and targets 110 nt. The two annealing arms (denoted extension and ligation arm) together are 40 nt and are connected using a common linker sequence of 30 nt. In addition, an 8-nt random tag serves as “single molecule” identifier (Eijkelenboom et al., 2016). The smMIPs were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Leuven, Belgium). All smMIPs were phosphorylated after pooling, as described previously (Neveling et al., 2017).

2.3 Automated smMIPs library preparation and sequencing

ABCA4 sequencing libraries were prepared using a fully automated sequencing workflow based on smMIPs enrichment in combination with multiplex-PCR using barcoded PCR primers in two series, followed by sequencing with Illumina NextSeq 500 (by using Mid output kits, maximum of 130 million reads) as described previously (Neveling et al., 2017).

2.4 Variant calling and annotation

Data were analyzed using an in-house bioinformatics pipeline starting from the raw sequencing reads (FASTQ). In the first step unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were trimmed from the sequencing reads and stored within the read identifier for later use. The paired-end sequencing reads were then directly mapped to the reference genome (human genome build GRCh37/hg19) using BWA mem (v0.7.12). The extension and ligation arms, as well as overlap between the read-pairs, were trimmed after the alignment of each read based on the smMIPs design file, to improve the initial alignment. Duplicated reads, located on the same position and having the same UMI, were removed while the remaining unique reads were written to a single BAM file per patient based on the barcode. Variants were called using both the UnifiedGenotyper as well as the HaplotypeCaller from GATK (v3.4–46) for each individual sample followed by merging of the two variant call sets using the GATK Combine Variants and joint genotyping functions. The two resulting VCF files were used as input for an in-house annotation pipeline where variants were annotated with effect predictions, gene information as well as frequency information from various population databases (Lelieveld et al., 2016).

2.5 Variant prioritization

First, variants were prioritized by using the criteria “Quality by Depth” >500, which represents the overall coverage of the region, an Allele frequency (AF) < 0.005 in the dbSNP database and in an in-house whole exome data set of 21,559 persons, and an AF < 0.01 in control population datasets, such as the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), and passing standard quality filters including gene components such as exons and canonical splice sites were prioritized. Previously reported pathogenic variants with high AFs such as c.2588G>C and c.5603A>T (AFs in non-Finnish European [nFE] in gnomAD 0.00784 and 0.06647, respectively) (Cornelis et al., 2017; F. P. Cremers et al., 1998; Schulz et al., 2017; Zernant et al., 2014, 2017), were selected separately. Known deep-intronic variants were selected based on prior knowledge from literature (Albert et al., 2018; Bauwens et al., 2015, 2019; Braun et al., 2013; Sangermano et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2017; Zernant et al., 2014).

2.6 Coding variants classification

For novel coding variants, along with the AF filters, in silico pathogenicity assessment was performed including Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT; http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) (Kumar, Henikoff, & Ng, 2009), Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2) (Adzhubei et al., 2010) and MutationTaster (Schwarz, Cooper, Schuelke, & Seelow, 2014) by using Alamut Visual software version 2.7 (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France; www.interactive-biosoftware.com). Variants were classified according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) (Richards et al., 2015).

| Genomic position (hg 19) | cDNA variant | Protein variant | AF in study | gnomAD_AF (nFE) | In silico analysis | ACMG class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIFT (scores) | Mutation Taster | PolyPhen-2 (scores) | ||||||

| 94574132 | c.442+1G>A | p.(?) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94564408 | c.710T>C | p.(Leu237Pro) | 0.00122 | 0.000008952 | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Prob. dam. (1.000) | 3 |

| 94549602 | c.769−605T>C | p.(=) | 0.00365 | 0.00612925 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1 |

| 94544258 | c.1244A>G | p.(Asn415Ser) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Pos. dam. (0.870) | 4 |

| 94544253 | c.1249A>G | p.(Thr417Ala) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Pos. dam. (0.745) | 4 |

| 94543346 | c.1454del | p.(Gly485Alafs*83) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94528667 | c.1760+1G>A | p.(?) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94520760 | c.2494G>T | p.(Asp832Tyr) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Pos. dam. (0.797) | 3 |

| 94520684 | c.2570T>C | p.(Leu857Pro) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0.01) | Disease causing | Prob. dam. (0.969) | 3 |

| 94517247_94517248 | c.2594_2595del | p.(Tyr865Trpfs*19) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94512608 | c.2785dup | p.(Val929Glyfs*11) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94508473 | c.3191−19G>A | p.(=) | 0.00122 | 0.0001264 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3 |

| 94506943 | c.3344T>C | p.(Met1115Thr) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0.01) | Disease causing | Benign (0.062) | 5 |

| 94506788 | c.3499del | p.(Gln1167Argfs*29) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94502847 | c.3667dup | p.(Glu1223Glyfs*14) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94497515 | c.3947A>G | p.(Asp1316Gly) | 0.00122 | – | Tolerated (0.41) | Polymorphism | Benign (0.00) | 3 |

| 94497514 | c.3948C>G | p.(Asp1316Glu) | 0.00122 | – | Tolerated (1) | Polymorphism | Benign (0.00) | 3 |

| 94497334 | c.4128G>C | p.(Gln1376His) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Prob. dam. (1.000) | 5 |

| 94495001 | c.4539G>A | p.[Cys1490Glufs*12,=] | 0.00243 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94494142 | c.4539+859C>T | p.(=) | 0.03285 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3 |

| 94492936 | c.4539+2065C>G | p.[Arg1514Lysfs*35,=] | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94490511 | c.4633A>G | p.(Ser1545Gly) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Benign (0.002) | 5 |

| 94492937 | c.4706del | p.(Val1569Alafs*12) | 0.00852 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94486887 | c.4927del | p.(Leu1643Cysfs*19) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94485185 | c.5149G>T | p.(Gly1717*) | 0.00243 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94485159 | c.5175dup | p.(Thr1726Aspfs*61) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94480248 | c.5313−2del | p.(?) | 0.00243 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94480230 | c.5329A>T | p.(Met1777Leu) | 0.00122 | 0.0001263 | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Benign (0.008) | 3 |

| 94480106 | c.5453del | p.(Asn1818Ilefs*12) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94476893 | c.5509C>T | p.(Pro1837Ser) | 0.00243 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Prob. dam. (1.000) | 5 |

| 94476366 | c.5704dup | p.(Leu1902Profs*10) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94471044 | c.6100del | p.(Tyr2034Thrfs*27) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94467468 | c.6228del | p.(Lys2076Asnfs*39) | 0.00122 | – | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5 |

| 94467442 | c.6254T>C | p.(Leu2085Pro) | 0.00122 | – | Deleterious (0) | Disease causing | Prob. dam. (0.998) | 4 |

- Note: Novel rare variants found in study cohort and their classification. Data for all the novel coding variants identified in this study is provided with their genomic and cDNA positions (human genome version 19; hg19) and predicted effect at the protein level. SIFT scores range from 0 to 1 and amino acid substitutions are predicted damaging if the score is ≤0.05 and tolerated if the score is >0.05. Mutation Taster had probability-values of 1 for Disease causing variants and those designated to be Polymorphic. PolyPhen-2 scores range between 0.000 and 1.000 are shown (scores close to 1 indicate damaging effect of variants). All the variants were classified according to the ACMG guidelines from Class 1 to 5 (1, benign; 2, likely benign; 3, variant of unknown significance; 4, likely pathogenic; 5, pathogenic).

- Abbreviations: ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; AF, allele frequency; n.a., not applicable; nFE, non-Finish European; Pos. dam, possibly damaging; Prob. dam, probably damaging; SIFT, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant.

2.7 Noncoding variants classification

For the selection of noncanonical splice site (NCSS) and deep-intronic variants, in silico predictions were performed by using five algorithms (SpliceSiteFinder-like, MaxEntScan, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer, Human Splicing Finder) via Alamut Visual software version 2.7 (Biosoftware, 2014; Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France; www.interactive-biosoftware.com) (Cartegni, Wang, Zhu, Zhang, & Krainer, 2003; Desmet et al., 2009; Pertea, Lin, & Salzberg, 2001; Reese, Eeckman, Kulp, & Haussler, 1997; Yeo & Burge, 2004) by comparing splicing scores for wild-type (WT) and variant nucleotides (Table S2).

2.8 Segregation analysis

Segregation analysis was performed for 45 cases from Lille. PCR products were sequenced in sense and antisense directions using the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on a 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA).

2.9 Midigene-based splice assay and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assessment

The effect of seven NCSS and three deep-intronic variants was assessed by midigene-based splicing assays employing wild-type (WT) BA constructs described elsewhere (Sangermano et al., 2018) and a newly designed BA31 construct (Table S3). Details of mutagenesis primers and sequencing primers are given in Table S4. WT and mutant constructs were transfected in Human Embryonic Kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells and the extracted total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, as previously described (Sangermano et al., 2018).

3 RESULTS

3.1 smMIPs performance

Sequence analysis of 16 STGD1 cases carrying known ABCA4 pathogenic variants and four control samples using 483 smMIPs and a NextSeq 500 mid-output kit was performed to assess the performance of each smMIP and coverage per patient. The average read for these 20 DNA samples ranged from 10 to 37,551 per smMIP, with an overall average coverage of 2,687×. A coverage plot of the smMIPs is provided in Figure S2. All previously known 34 variants present in the 32 alleles were identified robustly. All the targeted deep-intronic variants were found in ≥31% of the total reads ranging from 1,521 reads (c.859–506G>C) to 17,538 reads (c.5196+1137G>A) (Table S5). Thereafter, 411 STGD1 proband samples were sequenced in two subsequent runs, with 226 samples (average coverage 511×) and 185 samples (average coverage 655×).

3.2 Identification of ABCA4 variants

ABCA4 sequencing was performed using 483 smMIPs in 411 STGD1 persons, identifying 173 unique sequence variants. All variants and the respective cases were uploaded into the ABCA4 LOVD at www.lovd.nl/ABCA4. Of these, 34 (20%) were new variants, including coding, NCSS, and deep-intronic variants, as listed in Table 1. The 173 unique variants account for 534 alleles in STGD1 patients, details of which are given in Table S6. Of these 173 variants, 75% (n = 131) are coding variants, comprised of missense (n = 96), frameshift (n = 23), and nonsense mutations (n = 12). The other 25% (n = 42) of variants are located in noncoding regions including canonical splice site, NCSS, and deep-intronic variants.

The most common previously reported alleles were c.4253+43G>A (n = 28), c.[5461-10T>C;5603A>T] (n = 22), c.5882G>A (n = 22), c.[1622T>C;3113C>T] (n = 14), c.[2588G>C; 5603A>T] (n = 13) and c.5196+1137G>A (n = 13) (Table S7). The most frequent single variant allele was c.5603A>T (n = 144), but its penetrance, when present in trans with a severe ABCA4 variant, is incomplete in STGD1 families and in the Dutch population (see below).

3.3 Disease-associated ABCA4 alleles in 411 STGD1 persons

Two or more pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in ABCA4 were found in 155 of 411 STGD1 cases, 97 (24%) of whom were considered solved as they carried two (likely) pathogenic variants. Another 58 (14%) cases were considered possibly solved as they carry c.5603A>T (p.Asn1868Ile), a frequent mild but low-penetrant variant (F. P. M. Cremers, Cornelis, Runhart, & Astuti, 2018; Runhart et al., 2018; Zernant et al., 2017) in trans with a moderate or severe coding or deep-intronic variant. Details of the identified alleles in each person are given in Table S7. Sixty-seven individuals carry complex alleles (Tables S7 and S8). In 133 (32%) STGD1 cases only one ABCA4 allele was identified whereas in 123 (30%) of the persons, no variants were identified in ABCA4.

3.4 Novel rare variants identification and classification

Thirty-four novel variants were identified in 534 identified alleles (Table 1). Among these, 13 variants were missense mutations, identified in 14 alleles, of which c.4128G>C (p.Gln1376His) and c.4633A>G (p.Ser1545Gly), were also situated in consensus splice site sequences of exons 28 and 31, respectively. Thirteen frameshift mutations were identified in 19 alleles (among which c.4706del, p.Val1569Alafs*12 in seven alleles), and three canonical splice site variants (c.442+1G>A, c.1760+1G>A, and c.5313–2del). One stop mutation, p.Gly1717* was identified in two alleles. In addition, a synonymous variant (c.4539G>A) was located in the splice donor site (SDS) sequence of exon 30 in two alleles, and variant c.3191–19G>A was situated close to exon 22 but not in consensus splice site sequences. Moreover, three novel deep-intronic variants (c.769–605T>C, c.4539+859C>T and c.4539+2065C>G) were identified in six alleles.

3.5 Splice defects due to selected ABCA4 noncanonical splice site variants

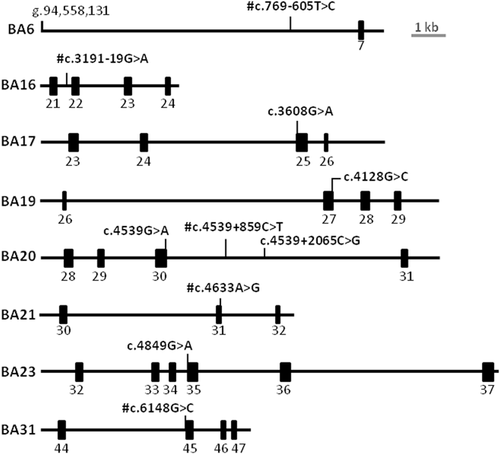

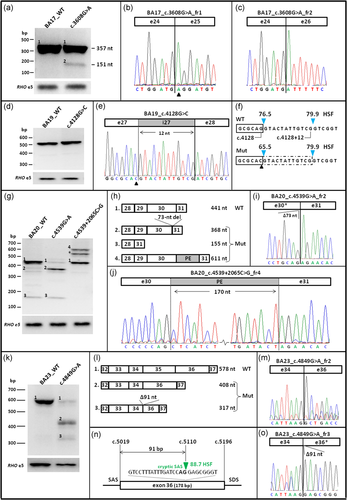

In vitro splice assays were performed in HEK293T cells to assess the impact of NCSS and novel near-exon at the transcript level by using eight WT constructs shown in Figure 1. Four of eight tested NCSS or near-exon splice site variants show splice defects: c.3608G>A, c.4128G>C, c.4539G>A and c.4849G>A. RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing results are provided in Figure 2. Variant c.3608G>A, reported previously by Cornelis et al. (2017) was predicted to reduce the strength of the SAS of exon 25 and the creation of a cryptic SAS 2 nt downstream of the canonical SAS (Table S2). It was tested in WT construct BA17 and RT-PCR was performed by using ABCA4 exonic primers located in exons 23 and 26. A fragment of 357 nt corresponding to the WT band and a 151-nt fragment in which exon 25 is skipped were observed (Figure 2a–c).

Overview of midigene splice constructs containing novel variants. #Variants showing no splice defects when tested in HEK293T cells (Figure S3). Exons are represented as black rectangles

Overview of splice defects due to three noncanonical splice site variants and one deep-intronic variant in ABCA4. All WT and Mut midigenes were transfected in HEK293T cells and their RNA subjected to RT-PCR. (a) RT-PCR for WT and c.3608G>A Mut BA17 midigene showed a splice defect when using primers in ABCA4 exons 23 and 26. Fragment 1 of 357 nt corresponds to the correct mRNA and fragment 2 of 151 nt corresponds to exon 25 skipping. (b, c) Sanger sequencing of mutant fragment 1 with a missense change (c.3608G>A) highlighted by a triangle, and fragment 2 corresponding to the skipping of exon 25. (d–f) RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing of cDNA corresponding to mutant c.4128G>C resulting in a 12-nt exon 27 elongation. HSF splice site scores (blue arrowheads) for wild-type and mutant sites. (g–j) RT-PCR for WT and Mut (c.4539G>A and c.4539+2065C>G) midigenes showed a complex splice pattern when analyzed using primers in ABCA4 exons 28 and 31. Variant at the last position of exon 30 resulted in a correct transcript (fragment 1), a deletion of 73 nt of the 3′-end of exon 30 (fragment 2) and a deletion of both exons 29 and 30 (fragment 3). Variant c.4539+2065C>G, in addition to the correct fragment 1, resulted in a 170-nt PE inclusion between exons 30 and 31 (fragment 4). Asterisks denote to a heteroduplex fragment consisting of fragments 1 and 4. (k, l) RT-PCR products of WT and Mut BA23 containing a noncanonical splice site variant at the first nucleotide of exon 35. Primers in exon 32 and 37 revealed skipping of exon 35 alone (fragment 2) or skipping of exon 35 in combination with a 91-nt deletion of the 5′-end of exon 36 (fragment 3). (m) Exon 35 skipping confirmed by Sanger sequencing of fragment 2. (n, o) The 91-nt deletion of exon 36 is the result of the use of a cryptic SAS located at position c.5110, as confirmed by Sanger sequencing. cDNA, complementary DNA; HSF, Human Splice Finder; mRNA, messenger RNA; Mut, mutant; PE, pseudoexon; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; SAS, splice acceptor site; WT, wild-type

The novel missense variants residing in splice site consensus sequences, that is, c.4128G>C and c.4633A>G, were tested in WT constructs BA19 and BA21, respectively. Variant c.4128G>C, predicted to weaken the SDS of exon 27, resulted in a single band corresponding to a 12-nt elongation of exon 27 due to the presence of a cryptic SDS (Figure 2d–f). Variant c.4633A>G, predicted to significantly weaken the SDS of exon 31, showed no splice defect in HEK293T cells (Figure S3).

The novel synonymous variant c.4539G>A, predicted to impair the SDS of exon 30 (Table S2), was tested in midigene BA20. RT-PCR was performed by using primers residing in exons 28 and 31, and variant c.4539G>A showed three bands compared to the WT which upon sequencing revealed a band of 441 nt corresponding to WT, a band of 368 nt corresponding to a deletion of 73 nt of the 3′-end of exon 30 and the third band of 155 nt corresponding to the deletion of exons 29 and 30 (Figures 2g–i).

Variant c.4849G>A, also described previously (Downs et al., 2007) and predicted to reduce the SAS of exon 35, resulted in three fragments when tested in WT BA23. Sanger sequencing revealed a fragment of 578 nt corresponding to the correct transcript, a band of 408 nt corresponding to exon 35 skipping and the third band of 317 nt corresponding to the skipping of exon 35 and a 91-bp reduction of exon 36 due to the recognition of an internal SAS at position c.5110 (Figure 2k–o).

The other novel variant c.3191–19G>A, tested in BA16, did not show a splice defect (Figure S3). In addition to this novel splice variant, the previously reported variant c.6148G>C (Schulz et al., 2017) did not show a splice defect using BA31 (Figure S3).

3.6 Deep-intronic variants identification and in vitro assessment

To investigate the occurrence of deep-intronic variants among 411 STGD1 persons, 12 selected intronic regions carrying 14 previously identified variants were targeted by smMIPs. Among 534 alleles, 67 alleles carrying different deep-intronic variants were identified (Table S7). Ten already reported deep-intronic variants were identified in 61 (15%) alleles, that is, c.769–784C>T (four alleles), c.4253+43G>A (28 alleles), c.4539+1106C>T (one allele), c.4539+2001G>A (three alleles), c.4539+2028C>T (one allele), c.4539+2064C>T (seven alleles), c.5196+1056A>G (one allele), c.5196+1136C>A (one allele), c.5196+1137G>A (13 alleles) and c.5196+1159G>A (two alleles).

In addition, three novel deep-intronic variants, that is, c.769–605T>C (three alleles), c.4539+859C>T (two alleles) and c.4539+2065C>G (one allele), were found in the regions containing known causal variants. Variant c.769–605C>T, showing an allele frequency of 0.00613 in non-Finnish Europeans, was located 12 nt downstream of a pseudoexon (PE) generated by c.769–784C>T. It was tested in WT construct BA6 but did not show a splice defect (Figure S3). Similarly, variant c.4539+859C>T, showing an allele frequency of 0.01123 in non-Finnish Europeans in gnomAD, was located upstream of variant c.4539+1106C>T and increased the strength of the existing cryptic SAS in the intronic region. It was tested in WT construct BA20 but did not show any splice defect (Figure S3).

Conversely, variant c.4539+2065C>G (not found in 7713 non-Finnish Europeans), located next to c.4539+2064C>T, creates a new SD and alters the strength of ESEs in the region predicted by Alamut visual. It was also tested in WT construct BA20 and RT-PCR was performed by using ABCA4 exonic primers located in exons 28 and 31. Gel analysis and Sanger sequencing revealed a band of 441 nt corresponding to the WT and 611 nt corresponding to a 170-nt PE insertion located between c.4539+1891 and c.4539+2060, that was observed in most of the cDNA product and led to a frameshift p.[Arg1514Lysfs*35,=] (Figure 2g, h, j).

Therefore, a total of 11 causal deep-intronic variants were found in 62 STGD1 alleles. Most carried deep-intronic variants on one allele and a severe or a moderately severe ABCA4 variant on the other allele. Two patients carried causal deep-intronic variants on both alleles, that is, individual 067332 (c.4539+2064C>T, p.[=,Arg1514Leufs*36] and c.5196+1137G>A, p.[=,Met1733Glufs*78]) and individual 067241 (c.4539+2064C>T and c.4253+43G>A, p.[=,Ile1377Hisfs*3]). Two other individuals, 066666 and 066688, carried c.4539+859C>T, p.(?) and c.4253+43G>A in a compound heterozygous manner, but the former variant was not shown to result in a splice defect.

4 DISCUSSION

To identify the missing causal variants in STGD1 cases, all 50 exons and 12 selected intronic regions of ABCA4 were sequenced in 411 previously genotyped cases by employing 483 overlapping smMIPs. In total, 173 unique sequence variants were identified in 534 alleles, solving at least 24% of the cases. Twenty percent of the variants were novel. The novel NCSS variant c.4128G>C showed a 12-nt elongation of exon 27 and variant c.4539G>A resulted in skipping of exon 30.

Ten previously detected deep-intronic variants and the novel c.4539+2065C>G were identified in 15% (62) of the alleles. Variants c.4253+43G>A and c.5196+1137G>A were identified in 28 and 13 alleles, respectively, highlighting their relatively high frequency in this patient cohort. The novel deep-intronic variant c.4539+2065C>G led to the generation of a 170-nt PE in intron 30. This PE was observed as part of one of three splicing products due to c.4539+2064C>T, that is, a 244-nt PE consisting of the 170-nt PE associated with c.4539+2065C>G, as well as a neighboring 74-nt PE (Bauwens et al., 2019).

A common c.5603A>T (p.Asn1868Ile) variant, strongly associated with late-onset STGD1 (F. P. M. Cremers et al., 2018; Runhart et al., 2018; Zernant et al., 2017), was found in a heterozygous manner as a single variant in 144 STGD1 cases. It was previously shown that p.Asn1868Ile contributes to the pathogenicity of variants c.769–784C>T and c.2588G>C, which was consistently found in cis in patients and much less frequent in healthy persons (Sangermano et al., 2019; Zernant et al., 2017).

A pathogenic role was established for one of the three newly identified deep-intronic variants, c.4539+2065C>G, when tested in HEK293T cells. However, the disease-causing effect of the other two variants c.769–605T>C and c.4539+859C>T cannot be ruled out based on in vitro midigene splice assays, as many deep-intronic variants have shown to be disease-causing only when tested in patient-derived cells due to retina-specific splice factors which are missing in HEK293T cells (Albert et al., 2018).

Despite the identification of many causal variants, 62% of STGD1 cases remained unsolved either with one (32%) or no (30%) variant. It is of note that the 411 tested probands originate from a total of 1,468 STGD1 and macular dystrophy cases that were screened previously using different genotyping methods, that is, exon and splice site mutation scanning for 1,133 French cases, and exon and splice site sequencing for 335 German cases. This means that the 411 tested probands represent a highly biased patient cohort. Nevertheless, we identified many new variants, including NCSS and deep-intronic variants. The absence of ABCA4 variants in the unsolved cases could first of all be due to genocopies, as several other genes have been implicated in STGD-like phenotypes (Ma et al., 2019; Zaneveld et al., 2015). In view of the high AF of ABCA4 variants (5%) in the general population (Cornelis et al., 2017; Maugeri et al., 1999), our cohort may contain 40 mono-allelic ABCA4 cases that in fact are due to variants in these other genes. Second, we also may have missed noncoding variants residing in noncovered sequences as the smMIPs covered ~16,500 bp, leaving ~111,500 bp of intronic sequences unscreened. Third, we may have used too stringent variant selection criteria when using in silico algorithms. Fourth, the midigene in vitro splice assay that is performed in human embryonic kidney cells is insensitive to retina-specific splice defects (Albert et al., 2018). Finally, several types of structural variations such as inversions and insertions may have been missed as they are refractory to smMIPs detection.

By employing smMIPs-based ABCA4 sequencing, a large number of cases could be simultaneously sequenced for variants in ~11,500 bp, with an average coverage of 583×. In recent studies (Tayebi et al., 2019; Weisschuh et al., 2018), 647,547 bp was sequenced using 6,129 MIPs targeting 1,524 coding regions of 108 retinal dystrophy-associated genes, with an average coverage of 213x per MIP. This is comparable to other targeted sequencing methods such as WES or Haloplex-based sequencing. smMIPs-based ABCA4 sequencing is a cost-effective method compared to Sanger sequencing (≥€500 for 50 exons) and WES, since it costs ~€20 for reagents only (excluding the smMIPs design and synthesis) to sequence ABCA4 50 exons and 12 deep-intronic regions which are 25–50-fold less than Sanger sequencing or WES (Schwarze, Buchanan, Taylor, & Wordsworth, 2018). Other advantages of smMIPs are the low input of DNA per patient. We used 100 ng, but as low as 19 ng of DNA can be sufficient (Eijkelenboom et al., 2016). Moreover, due to the small target size (140 bp including the annealing primers) many fragmented DNA samples could also be effectively used for sequence analysis. Finally, the ability to detect CNVs with smMIPs data was assessed previously by Neveling et al. (2017). By including five positive control samples in three different sequencing runs with a mean coverage per smMIP of 359×, analytical sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 88% were obtained, respectively (Neveling et al., 2017). Flexibility, automation and its sensitivity for single nucleotide variants and CNVs render the smMIP technology very attractive for diagnostic requirements. A detailed comparison of smMIPs-based sequencing with other targeted and nontargeted sequencing methods is given in Table S9. smMIPs-based sequencing can be the preferred method when the number of samples to be sequenced is (very) high, additional targets should be added in the future, DNA quality and quantity are low, and a NGS platform is available for high throughput analysis.

In conclusion, we identified causal deep-intronic variants in 15% of our genetically unexplained STGD1 cases, two of which (c.4253+43G>A and c.5196+1137G>A) are frequent. In addition, we identified four exonic NCSS variants that resulted in splice defects and one novel deep-intronic variant resulting in pseudoexon formation. Interestingly, many studies have shown the correction of ABCA4 splice defects caused by deep-intronic variants at the transcript level both in vitro and in vivo, providing a basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies for individuals with STGD1 carrying deep-intronic variants (Albert et al., 2018; Sangermano et al., 2019). To find the missing variants in the deep-intronic regions, additional smMIPs can be designed to cover the complete ABCA4 gene.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Béatrice Bocquet, Hélène Dollfus, Isabelle Drumare, Emeline Gorecki, Christian P. Hamel, Karsten Hufendiek, Cord Huchzermeyer, Herbert Jägle, Ulrich Kellner, Valérie Pelletier, Yaumara Perdromo, Charlene Piriou, Philipp Rating, Klaus Rüther, Eric Souied, Georg Spital, and Xavier Zanlonghi for their cooperation and ascertaining STGD1 cases. SmMIP hybridization, library preparation and NextSeq 500 sequencing was performed at the Genome Technology Center, Department of Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen. This work was supported by the Retina UK grant GR591 (to F. P. M. C. and S. Albert), a Fighting Blindness Ireland grant (to F. P. M. C., J. Farrar, and S. Roosing), the FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN programme EyeTN, agreement 317472 (to F. P. M. C.), the Foundation Fighting Blindness USA, grant no. PPA-0517-0717-RAD (to A. Garanto, F. P. M. C., R.W.J. Collin), the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, the Stichting Blindenhulp, and the Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden (to F. P. M. C.), and by the Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden, Macula Degeneratie fonds and the Stichting Blinden-Penning that contributed through Uitzicht 2016-12 (to F. P. M. C.). This work was also supported by the Algemene Nederlandse Vereniging ter Voorkoming van Blindheid and Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden that contributed through UitZicht 2014-13, together with the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, Stichting Blindenhulp and the Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden (to F. P. M. C.). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research, and provided unrestricted grants.