The value of genomic variant ClinVar submissions from clinical providers: Beyond the addition of novel variants

For the ClinGen/ClinVar Special Issue

Abstract

With the increasing use of clinical genomic testing across broad medical disciplines, the need for data sharing and curation efforts to improve variant interpretation is paramount. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ClinVar database facilitates these efforts by serving as a repository for clinical assertions about genomic variants and associations with disease. Most variant submissions are from clinical laboratories, which may lack clinical details. Laboratories may also choose not to submit all variants. Clinical providers can contribute to variant interpretation improvements by submitting variants to ClinVar with their own assertions and supporting evidence. The medical genetics team at Geisinger's Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute routinely reviews the clinical significance of all variants obtained through clinical genomic testing, using published ACMG/AMP guidelines, clinical correlation, and post-test clinical data. We describe the submission of 148 sequence and 155 copy number variants to ClinVar as “provider interpretations.” Of these, 192 (63.4%) were novel to ClinVar. Detailed clinical data were provided for 298 (98.3%), and when available, segregation data and follow-up clinical correlation or testing was included. This contribution marks the first large-scale submission from a neurodevelopmental clinical setting and illustrates the importance of clinical providers in collaborative efforts to improve variant interpretation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Broad genomic diagnostic technologies have been incorporated into routine clinical testing in many areas of medicine. Chromosomal microarray (CMA) is a first-tier test for patients with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability/developmental delay, and/or multiple congenital anomalies and for the prenatal evaluation of a fetus with structural anomalies (Manning & Hudgins, 2010; Muhle et al., 2017; Wapner et al., 2012). Gene panels have often been used in the evaluation of genetically heterogenous disorders, such as hearing loss, neurological disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and hereditary cancer syndromes, whereas whole exome sequencing (WES) is increasingly employed for pediatric and adult patients when there is a broad differential diagnosis or for those with non-specific features (ACMG Board of Directors, 2012). These testing options have provided a diagnostic boon due to the breadth of genomic regions and genes interrogated. However, they have also resulted in a large number of rare variants of uncertain significance (VUS), requiring extremely large case and control datasets to help inform interpretation (Coe et al., 2014; Firth et al., 2009; Lek et al., 2016). Data sharing across laboratories has emerged as a critical strategy to move variant interpretation efforts forward.

To facilitate this large-scale data sharing, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) created the ClinVar database, which serves as a repository for clinical assertions about genomic variants, their associations with disease, and any supporting evidence provided with the submission (Azzariti et al., 2018; Landrum et al., 2014; Landrum et al., 2016). The majority of ClinVar submissions come from clinical laboratories and are submitted as aggregate assertions, which therefore lack detailed case-level clinical descriptions and relevant family history information. While laboratories recognize the importance of clinical providers relaying details about a patient's clinical presentation, family history, and pertinent negative testing at the time of testing, this information is also important for variant curation efforts and other clinical providers who search for variants in ClinVar (Bush et al., 2017; Richards et al., 2015; Riggs, Jackson, Miller, & Van Vooren, 2012; Wain et al., 2012).

The clinical provider's role in variant interpretation is increasingly being recognized (Baldridge et al., 2017; Bland et al., 2018; Wain, 2018; Zirkelbach et al., 2017). The clinical provider is best suited to determine the most salient aspects of a patient's clinical history and is in the position to complete necessary post-test evaluations that can be key to informing a variant's interpretation, such as imaging, familial testing, or specialist referrals. Additionally, the clinical provider must make diagnoses and clinical recommendations based on the laboratory finding in the context of clinical correlation and judgment, a responsibility which relies on the clinical provider's unique expertise and assessment of the variant (Baldridge et al., 2017; Bland et al., 2018; Zirkelbach et al., 2017). Clinical specialists who have accumulated this expertise have a perspective that is valuable in variant interpretation and curation efforts. Working in partnership with NCBI, the NIH-funded Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) is an international, collaborative effort to improve genomic medicine through multiple initiatives, including gene and variant curation, which incorporate the expertise of laboratory and clinical providers with particular disease expertise (Rehm et al., 2015).

From a research perspective, data sharing is increasingly supported, and sometimes required, by professional societies, funding institutions, and publishers (ACMG Board of Directors, 2017; American Medical Association, 2013; Barsh et al., 2015; National Institutes of Health, 2014; National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2015). Clinical providers who value the dissemination of their clinical experience, in the form of case reports/series or other research publications, may be increasingly asked to submit variants to ClinVar or another database. Such submissions can help facilitate future research and variant identification via bioinformatics pipelines, which utilize ClinVar data annotations (Eilbeck, Quinlan, & Yandell, 2017; Harrison et al., 2016).

We report the first large submission of clinically reported genomic variants to ClinVar by Geisinger's Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute (ADMI), a pediatric multidisciplinary neurodevelopmental clinical team. These variants, identified through routine clinical genomic testing for patients with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability/developmental delay, and/or multiple congenital anomalies, are submitted along with the clinical team interpretations of the variants and additional phenotypic or other clinical testing details that enhance the utility of the data in ClinVar.

2 METHODS

This ClinVar data submission proposal was reviewed by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was determined to not meet the definition of research. Explicit consent was not required and no identifying information was included in the submission. Patients at ADMI are offered participation in our IRB-approved Making Advances Possible (MAP) protocol, which allows the use of clinically obtained data, including genomic test results, to be used for research purposes. Approximately 95% of patients and their families who are invited to participate gave consent to the project. Data for this ClinVar submission were drawn from MAP-consented individuals.

A cascade genomic testing approach, including FMR1 analysis, CMA, and WES, is the standard of care for patients who are evaluated at ADMI and diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, global developmental delay, intellectual disability, and/or multiple congenital anomalies. All testing is ordered as part of routine clinical care and insurance coverage is determined prior to ordering each step of the cascade. ADMI has generally been successful in obtaining insurance coverage for these clinical tests through commercial plans; many of our patients are insured by a Geisinger Health Plan policy, including a Geisinger Medicaid plan, which provides coverage for WES for patients with the above indications. Single gene or gene panel testing is considered on a case-by-case basis, typically for patients with very specific phenotypic presentations or insurance coverage gaps.

The ADMI medical genetics team routinely assesses the clinical significance of variants obtained through clinical testing by critically reviewing available gene and variant-specific evidence and seeking additional evidence that might not be specified in the laboratory report. Evidence is evaluated using published guidelines for copy number and sequence variants from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the ACMG/Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), respectively (Kearney, Thorland, Brown, Quintero-Rivera, & South, 2011; Richards et al., 2015). These assessments are led and managed by the clinical genetic counseling team as part of routine clinical care, with discussion of clinical correlation and the need for follow-up clinical evaluations, such as imaging, biochemical testing, or familial genetic testing and phenotyping for segregation analysis, occurring amongst the entire multidisciplinary clinical team. Any discrepancies between the ADMI clinical team and the laboratory interpretations are discussed with the testing laboratory to reach consensus, if possible.

Genomic test results from MAP-consented probands were queried and variants were selected for ClinVar submission. Copy number variants (CNVs) representing well-documented, recurrent chromosomal deletion or duplication syndromes were excluded. Five CNVs could not be submitted due to incomplete data or because the CNV was reported on a genome build not supported by ClinVar (hg17). Non-recurrent CNVs were submitted to ClinVar, but were not considered completely novel submissions in our data analysis if overlapping CNVs with very similar genomic breakpoints had been previously submitted. Additionally, two sequence variants were excluded because they are well documented in ClinVar, and our data provided no additional value.

Phenotype data were provided using terms from the Human Phenotype Ontology (Köhler et al., 2017; Robinson & Mundlos, 2010), as well as in a narrative comment field description. Five initial variants were submitted as a proof of concept in April 2017 (SUB2634283) using the “SubmissionTemplateLite” file via the ClinVar Submission Portal, with “clinical testing” as the collection method. An additional 143 sequence variants and 155 CNVs were submitted to ClinVar using the standard “SubmissionTemplate” Excel submission file and the newly developed collection method of “provider interpretation” (SUB3843551, sequence variants; SUB3918644, CNVs on GRCh37; SUB3918759, CNVs on GRCh36) (Landrum et al., 2018). The “provider interpretation” collection method includes the testing laboratory that identified the variant, the laboratory's interpretation, and the report date. These data can help ClinVar users understand that both the clinician and reporting laboratory may submit the variant and additional information about the variant to the database (Landrum et al., 2018).

3 RESULTS

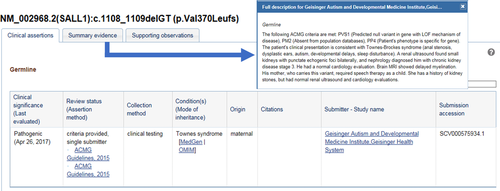

Out of 417 total variants obtained through clinical testing, we submitted 303 variants to ClinVar, including 148 sequence variants (from 120 genes) and 155 CNVs, from 215 independent probands. Probands may have had more than one variant identified across multiple tests. A brief clinical description of the proband and relevant family history was provided, including any relevant follow-up evaluations, such as imaging, blood tests, or specialist referrals (Figure 1). While complete details of all variants identified in an individual were not included to reduce risk of identification, the presence of another diagnostic genetic finding or a variant identified in trans were included for interpretive utility. Overall, 298 (98.3%) of our clinical provider submissions included detailed phenotypic descriptions, 165 (55.4%) included familial segregation data, and 67 (22.1%) included clinical correlation or follow-up clinical evaluation information.

Importantly, most variants (63.4%) had not been previously submitted to ClinVar [87 sequence variants (58.8%) and 105 CNVs (67.7%)], despite Geisinger's institutional preference for using clinical genetic testing laboratories that routinely share data. Of all clinically reported sequence variants, VUSs were less likely to have been previously submitted to ClinVar compared with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (P < 0.01, Fisher's exact test), but we did not observe this with CNVs. For those variants that had been previously submitted, 56 (50.5%) of our clinical provider submissions included documentation of literature not provided in the original submission.

In a small number of cases, the ADMI interpretation differed from the laboratory classification. In an attempt to resolve these discrepancies, the ADMI genetic counselor discussed any differences and the supporting evidence with the testing laboratory. At times, discussing these differences resulted in a changed interpretation by the clinical provider or the laboratory, but in three instances (2%) these differences were not fully resolved (Table 1). In the case of the family with a PTEN variant described in case example 2 below, the ADMI team's clinical expertise informed a higher confidence in clinical correlation, which allowed us to apply an additional ACMG/AMP criterion (PP1). Our clinical judgment resulted in a more conservative interpretation of the published literature in another case, and the third unresolved discrepancy was attributable to laboratory inclusion of unpublished internal data, to which we did not have access. We also observed 32 discrepancies in CNV classification due to outdated interpretation category terms, such as the use of “abnormal” or “positive” in older reports. In 31.3% of these, the ADMI interpretation was VUS, illustrating the importance of variant reassessment by clinical providers to ensure that up-to-date interpretations can be incorporated into clinical decision making.

| Gene (Transcript) | Variant | Relevant-associated disorder(s) | Lab interpretation | ADMI interpretation | Reason for difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN (NM_000314.4) | c.947T>C; p.Leu316Pro | - Macrocephaly/Autism Syndrome (OMIM #605309) | VUS | Likely pathogenic | Clinical correlation and segregation with proband, parent, and siblings |

| SCN2A (NM_021007.2) | c.3964G>A; p.Gly1322Arg |

|

Pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | A more conservative interpretation of case report documenting nearby amino acid changes that are not consistent with patient's phenotype |

| CACNA1E (NM_000721.3) | c.4777A>G; p.Ile1593Val | - Gene–disease association has not been fully determined | Likely pathogenic | VUS | Lack of published data supporting a clear gene–disease association; reference to internal data only in lab report |

The following are selected case examples that illustrate how clinical provider ClinVar submissions can be valuable for the clinical community, beyond simply submitting novel variants and regardless of the concordance between laboratory and clinical provider interpretation.

3.1 Case 1: Provision of post-test clinical outcomes and additional relevant literature citations

WES (trio analysis) was performed for a 5-year-old girl with global developmental delay, epilepsy, esotropia, a wide-based gait, and hypotonia. Her father had a history of learning disability and her mother had mild intellectual disability, epilepsy, and paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. A maternally inherited missense variant in SLC2A1 was identified (c.1199G>A, p.Arg400His). This variant has been previously reported in individuals with glucose transporter type 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut1DS, OMIM 606777) and was classified as pathogenic by the laboratory (Ito et al., 2015; Mullen et al., 2011; Vieker, Schmitt, Langler, Schmidt, & Klepper, 2012). This result provided a diagnosis for our proband and her mother. Both were referred for a nutrition consultation to discuss implementation of ketogenic diet. The proband, who is cared for by her paternal grandmother, has successfully adapted to the ketogenic diet with positive clinical outcomes. Her seizures have stopped and she has been successfully weaned from anti-epileptic medications. Additionally, accelerated developmental progress was observed across language, problem-solving, and motor developmental domains. While this variant had been previously submitted to ClinVar as a pathogenic variant, our clinical provider submission provided relevant phenotypic details for the proband and her affected mother, clinical outcomes after treatment, and clinically relevant literature not already referenced in ClinVar.

3.2 Case 2: Clinical correlation and judgment that impact variant interpretation

WES (trio analysis) was performed for a 6-year-old boy with autism spectrum disorder, global developmental delay, and borderline macrocephaly (>98th percentile). His father is macrocephalic and has a history of a significant speech delay, dysfluency, and a seizure disorder in adolescence that has since resolved. He also required learning supports throughout elementary and high school. The proband's brother is also macrocephalic and has a history of a speech delay. A paternally inherited missense variant in PTEN was identified (c.947T>C, p.Leu316Pro). The variant had not been reported previously in association with PTEN-related phenotypes and was classified by the laboratory as a VUS. Following a clinical genetics evaluation, the proband's affected brother and unaffected sister had targeted testing for the PTEN variant. The variant was identified in the proband's brother but not in the unaffected sister, indicating that the variant is segregating with macrocephaly and developmental delays in three informative meioses in this family. Therefore, the ADMI clinical team interpreted this variant as the likely cause of the proband's neurodevelopmental phenotype and classified it as likely pathogenic, using the following ACMG/AMP criteria (PM2, PP1, PP2, PP3, and PP4) (Richards et al., 2015). Clinical correlation provided by clinicians experienced in PTEN-related disorders enabled the confident application of the PP1 criterion, which the laboratory did not apply due to internal classification rules. While there is no known history of cancer in the family, all individuals with this variant were counseled about receiving surveillance based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network's guidelines for individuals with PTEN variants (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2018).

3.3 Case 3: Post-test follow-up clinical evaluations that inform variant interpretation and define genomic regions of clinical impact

CMA was performed for a 5-year-old girl with autism spectrum disorder, global developmental delay, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), wide-spaced teeth, and a history of feeding and sleep problems. A 142 kilobase, paternally inherited deletion was identified at 11p13 (chr11:31,312,348-31,454,239 × 1, GRCh37). Her father has a history of ADHD and bipolar disorder, though no history of learning difficulties. Similar deletions have been identified rarely in both cases and controls (Coe et al., 2014). This deletion is located telomeric to the PAX6 gene and the ELP4 gene, which is thought to harbor a PAX6 regulatory region (Balay et al., 2015). Loss-of-function or disruption of PAX6 is known to cause aniridia and other ophthalmologic abnormalities (Hingorani et al., 2003). The deletion was reported as a VUS due to lack of knowledge of this genomic region in general. Our patient was referred for an ophthalmologic evaluation, which was normal, and her father has normal vision. This post-test clinical evaluation supports the genomic boundaries of the proposed PAX6 regulatory region previously published (Balay et al., 2015), indicating that the deletion is outside of this regulatory region. However, the association of a deletion of this region with the patient's neurodevelopmental diagnoses and her father's psychiatric history remains uncertain.

4 DISCUSSION

As large-scale genomic testing has become more broadly incorporated into medical care, the number of novel, rare genomic variants identified has proven to be a major hurdle for the field of clinical variant interpretation. To address this challenge, genomic data sharing through ClinVar and other databases has emerged as a highly successful means of pooling data across clinical laboratories, researchers, the literature, and other stakeholders (Azzariti et al., 2018; Landrum et al., 2014; Landrum et al., 2016; Landrum et al., 2018). Data sharing has facilitated the resolution of interpretation discrepancies and is useful for bioinformatic approaches to clinical and research genomic testing (Eilbeck et al., 2017; Harrison et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Additionally, the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) has been instrumental in organizing and leading the collaborative curation of genes and variants to increase expert consensus of their medical relevance, a task in which clinical providers are engaged. Despite these strides, the role of the clinical provider as an active contributor to genomic variant data sharing efforts has not yet been fully realized.

Variant interpretation practices, such as searching variant databases and evaluating evidence according to published guidelines, are increasingly being acknowledged as relevant to clinical genetics providers’ practice (Baldridge et al., 2017; Bland et al., 2018; Wain, 2018; Zirkelbach et al., 2017), and educational sessions on this topic have been well attended at national genetics conferences (ACMG, 2017, 2018; NSGC, 2017). This clinical practice can also include reinterpretation of genomic variants over time, allowing the clinical provider to identify newly available literature and data that further informs interpretation and patient care. At ADMI, this clinical practice is within the purview of the genetic counseling team, who collaborate with the neurodevelopmental pediatricians, medical geneticist, and other specialists within a multidisciplinary setting to assess the interpretation of genomic variants, manage data, facilitate discussions regarding additional clinical correlation or follow-up testing, and counsel patients and families about their genetic results or updated variant interpretations. This process is part of routine clinical care, along with case preparation and post-test follow-up. As such, the time spent on variant interpretation activities varies between cases and is often dependent on the extent of the literature available about a given gene and/or variant. Submitting clinically obtained genomic variants to ClinVar as “provider interpretation” submissions allows the ADMI clinical team to contribute to the global genomic field in the following important ways.

4.1 Contribute variants that have not been shared previously

The majority of genomic variants (63.4%) identified in our patients through routine clinical testing had not been submitted to ClinVar previously, despite prioritizing the use of clinical laboratories that share data regularly. This observation demonstrates the invaluable contribution of clinical provider engagement in genomic variant data sharing, rather than relying only on clinical laboratories to build this shared resource. Large commercial laboratories typically have several distinct areas of disease or technical expertise and data sharing practices may not be consistent across all areas. Also, laboratories may choose to submit some types of variants and retain others, such as variants in genes of uncertain significance, within internal data only. These data sharing practices may be due to a perception that VUSs in ClinVar are less useful, time and workforce limitations, or laboratory decision to first gather internal data to facilitate publications and enable collaborations with ordering providers. While such partnerships and publications are valuable, these data sharing decisions can also delay the dissemination of information that may prove useful for a clinical provider at point-of-care. This practice also reduces the chance that genomic variants that are ultimately determined to be likely benign or benign are shared publicly because these variants are less likely to be published.

4.2 Provide detailed clinical descriptions

The importance of submitting patient phenotype and family history information to a testing laboratory for variant interpretation purposes has been acknowledged previously (Bush et al., 2017; Richards et al., 2015; Riggs et al., 2012; Wain et al., 2012). However, the clinical provider's role in the post-test evaluation of a patient's medical and/or family history can also provide critical information relevant to variant interpretation that was not available, or may not have seemed relevant, prior to testing. Therefore, post-test clinical correlation and relevant follow-up clinical assessments provide critical data for optimal variant interpretation, as shown in case examples 2 and 3. While best practice would include relaying this additional clinical impression to the laboratory, this may not always occur in practice, due to time constraints or variability between clinics (Bush et al., 2017). When additional information is provided to a laboratory, it may not result in an updated laboratory interpretation and test report. Additionally, it is difficult for a laboratory to fully appreciate the nuances of a clinical evaluation and clinical providers must be relied upon for clinical correlation. Many laboratory-submitted variants in ClinVar provide sparse clinical details about the patients in whom the variants were observed, even if this information was included on the test requisition form, typically because these variants are submitted in an aggregate form which excludes case-level detail. Therefore, clinical provider variant submissions are an opportunity to provide appropriately detailed descriptions of clinical presentations and histories, relevant medical assessments, family history details, segregation studies, and other pertinent genetic findings that can be lacking from existing ClinVar submissions. While the enhanced clinical detail provided by clinical provider submissions is valuable regardless of whether or not the clinical provider agrees with the laboratory interpretation, this information is particularly important for variants that a clinical provider interprets differently from the laboratory, as comments can include clinical judgment, such as “Clinical correlation was thought to be poor/good.”

4.3 Facilitate inclusion of updated interpretations and curation efforts

The clinical interpretation of a genomic variant is derived at a given point in time, using available evidence and resources and interpreted through the perspective of a given individual or laboratory. Thus, interpretations may change over time as new data become available and new interpretation guidelines are utilized. Clinical providers who engage in the critical evaluation of available literature or other genomic resources will also be able to reassess a variant's contribution to a patient's health as they care for patients over time. Therefore, ClinVar submissions from clinical providers provide an opportunity to include relevant recent publications, in addition to developmental, medical, or family history or segregation updates, that are considered in a variant's interpretation, including pertinent negative evaluations. Providing this information enhances the utility of ClinVar and allows one clinical provider's work to potentially help other providers who are caring for patients with the same or a similar genomic variant.

At times, the clinical provider may interpret the clinical significance of a variant differently than the laboratory, and these differences may not always be resolved through direct discussion. We observed this for three sequence variants (2%) from this data submission (Table 1). These instances reflect the need for the clinical provider to think about a variant's impact independently. In our experience, these interpretation differences were associated with three situations: (1) the clinical provider's ability to fully assess and be confident in the clinical phenotypes of a proband and family members, (2) a somewhat more conservative interpretation of published case reports by the clinical provider, and (3) the inability of the clinical provider to independently review unpublished laboratory internal data for a gene of uncertain significance. There may be multiple factors that could influence these situations. For example, our team's engagement with the ClinGen gene–disease curation efforts informed a more conservative interpretation of the CACNA1E variant, which we consider a gene of uncertain significance. Clinical provider ClinVar submissions ensure that this nuanced clinical perspective is considered in variant interpretation, gene and variant curation efforts, and variant discrepancy resolution activities.

4.4 Be informed of variants with updated interpretations

ClinVar submissions also provide a potential mechanism for the clinical provider to receive notifications about variant interpretation discrepancies, which may occur over time as variants are reclassified by other ClinVar submitters (Harrison et al., 2017; Landrum et al., 2016). Staying abreast of variant reclassifications has been acknowledged as a logistical challenge for clinical providers and has resulted in debate regarding where the responsibility for this lies: the laboratory, the clinical provider, the patient, and so on (Bowdin et al., 2016; Richards et al., 2015). For clinical provider submitters, ClinVar discrepancy notifications may be a more reliable means of alerting a clinical provider to a variant's reclassification than relying on laboratories to issue new reports. A laboratory that is actively sharing data is likely to submit updated interpretations to ClinVar over time, and expert panel variant curations will become increasingly available. However, policies regarding issuing updated genetic test reports and recontacting ordering providers vary between laboratories. Furthermore, if a genetics provider did not originally order the testing, an updated report may not be sent to them. Thus, if clinical provider ClinVar submissions can be included in discrepancy resolution activities, as these activities continue to expand, these submissions could have the potential to directly impact the care of a submitting provider's patients by promoting notification of variant interpretations that differ from those originally submitted.

4.5 Foster ongoing development and collaboration

Understanding how clinical providers approach variant interpretation can help foster professional development and education in this area. Familiarity with the ClinVar submission process is useful in helping clinical providers appreciate the benefits and limitations of the ClinVar database, and this understanding can help fuel additional input from these stakeholders regarding the use and design of ClinVar moving forward. For example, through our participation in ClinGen we were able to express our interest in clinical provider ClinVar submissions and contribute to the creation of the “provider interpretation” submission type (Landrum et al., 2018). While ADMI has an internal database that captured much of the data needed for this ClinVar submission, this initial large submission still involved manual curation requiring significant time over and above routine clinical practice. However, this experience has informed database improvements and changes to genetic counselors’ clinical practices that are expected to increase efficiency for subsequent submissions, case management, and future publications. Incorporating ClinVar submissions as a priority for clinical providers could spark improved genomic data organization and database infrastructure within the provider's institution, promoting the use of clinical data for research and healthcare improvements. As a learning healthcare system, Geisinger supports such clinical provider engagement and leverages such data to inform insurance policy updates and workflow improvements. Contributing to ClinVar could be a useful goal for a clinical team as they implement elements of variant interpretation into routine practice.

Finally, clinical provider submissions to ClinVar are an important means of ensuring that the nuanced assessments and judgments of clinical providers are available for ongoing gene and variant curation activities, including the curation of clinically relevant chromosomal regions. Data sharing improves variant interpretation by reducing the data silos created by individual laboratories. Further reducing the silos of accumulated clinical knowledge through clinical provider data sharing ensures that ClinVar can become a data resource that encompasses a broader range of expertise, making relevant clinical information and clinical provider judgment available for variant interpretation.

5 CONCLUSION

The Geisinger ADMI submission of sequence variants and CNVs to ClinVar as “provider interpretation” submissions marks the first large-scale submission from a neurodevelopmental clinical setting. This activity was valuable in several ways, including: (1) submission of novel variants to ClinVar (63.4%), (2) the provision of detailed patient descriptions (98.3%), segregation and family history information (55.4%), and relevant follow-up evaluations that can inform interpretation (22.1%), (3) inclusion of clinical provider judgment and experience in a variant's interpretation, such as differing interpretations or additional literature not included in a laboratory assessment, and (4) the value of the clinical provider voice in the development and improvement of genomic resources and curation efforts. Educational resources and continuing education opportunities that support clinical providers in variant interpretation and ClinVar submission will continue to be developed to facilitate this important mechanism for data sharing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge our patients and their families, and all members of the ADMI clinical team, who contributed to our efforts. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.