Identification of Novel Craniofacial Regulatory Domains Located far Upstream of SOX9 and Disrupted in Pierre Robin Sequence

Communicated by Jacques S. Beckmann

Contract grant sponsors: ANR (EvoDevoMut, CRANIRARE, and IHU-2010–001); NHMRC Training Fellowship (#607431); NIH Grants (R01HG003988, U01DE020060); SNSF Advanced Researchers Fellowship; Department of Energy (Contract DE-AC02–05CH11231).

ABSTRACT

Mutations in the coding sequence of SOX9 cause campomelic dysplasia (CD), a disorder of skeletal development associated with 46,XY disorders of sex development (DSDs). Translocations, deletions, and duplications within a ∼2 Mb region upstream of SOX9 can recapitulate the CD–DSD phenotype fully or partially, suggesting the existence of an unusually large cis-regulatory control region. Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) is a craniofacial disorder that is frequently an endophenotype of CD and a locus for isolated PRS at ∼1.2–1.5 Mb upstream of SOX9 has been previously reported. The craniofacial regulatory potential within this locus, and within the greater genomic domain surrounding SOX9, remains poorly defined. We report two novel deletions upstream of SOX9 in families with PRS, allowing refinement of the regions harboring candidate craniofacial regulatory elements. In parallel, ChIP-Seq for p300 binding sites in mouse craniofacial tissue led to the identification of several novel craniofacial enhancers at the SOX9 locus, which were validated in transgenic reporter mice and zebrafish. Notably, some of the functionally validated elements fall within the PRS deletions. These studies suggest that multiple noncoding elements contribute to the craniofacial regulation of SOX9 expression, and that their disruption results in PRS.

Introduction

SOX9 (MIM #608160) is an HMG-box transcription factor with multiple roles during embryonic development [reviewed in Pritchett et al., 2011]. Conditional deletion in mice has demonstrated that Sox9 is essential for the development of progenitors of chondrocytic, neuronal, pancreatic, and Sertoli lineages, amongst others. Sox9 also plays a role in the production of neural crest cells (NCCs) from the dorsal neural tube in several species [reviewed in Lee and Saint-Jeannet, 2011], and NCC-specific knockout mice fail to develop craniofacial cartilage [Mori-Akiyama et al., 2003]. In humans, haploinsufficiency of SOX9, due to coding mutations, results in campomelic dysplasia (CD; MIM #114290), a skeletal dysplasia often associated with disorders of sex development (DSDs). A frequent component of CD is Pierre Robin sequence (PRS; MIM #261800), which involves micro- and/or retrognathia, glossoptosis and cleft palate. PRS in its isolated form is a relatively frequent craniofacial anomaly, with the initiating event thought to be defective mandibular outgrowth, although the underlying genetic causes are unknown in the vast majority of cases [Tan et al., 2013]. Noncoding lesions (translocations, deletions, duplications) upstream of SOX9 have suggested a complex regulatory domain controlling tissue-specific expression of SOX9 during embryonic development. These lesions typically result in endophenotypes of complete CD, and approximate genotype–phenotype correlations can be made: within a 1 Mb domain upstream of SOX9, translocation breakpoints falling close to SOX9 typically result in CD, while those further upstream tend to result in acampomelic campomelic dysplasia (ACD; MIM #114290), a milder version of CD without limb involvement [reviewed in Leipoldt et al., 2007; Gordon et al., 2009]. A series of large duplications 0.78–1.99 Mb upstream were associated with brachydactyly anonychia (MIM #106995) [Kurth et al., 2009], while duplications, a triplication or deletions of a region 517–595 kb upstream lead to DSDs [Benko et al., 2011; Cox et al., 2011; Vetro et al., 2011]. Finally, a locus for isolated PRS has been identified at ∼1.2–1.5 Mb upstream of SOX9, based on the position of a translocation breakpoint cluster (TBC) [Jakobsen et al., 2007; Benko et al., 2009] and deletions falling immediately proximal to this TBC [Benko et al., 2009; Fukami et al., 2012; Sanchez-Castro et al., 2013].

Regulatory elements that drive reporter expression in specific tissues in transgenic mice have been identified in the region upstream of SOX9 [Wunderle et al., 1998; Bagheri-Fam et al., 2006; Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Benko et al., 2009; Mead et al., 2013]. The overlap of reporter expression with endogenous Sox9 expression supports the idea that disruption of these elements in patients with noncoding lesions result in CD endophenotypes due to perturbation of SOX9 expression in a restricted range of tissues. Mechanistically, individual elements, or regions containing many elements, may make contact with the SOX9 promoter to regulate expression, despite being separated from the gene by large distances in cis [Velagaleti et al., 2005; Maass et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Smyk et al., 2013] or in trans [Maass et al., 2012]. Candidate regulatory elements at the SOX9 locus have typically been selected for functional studies on the basis of conservation between distantly related species. However, only a small fraction of the conserved noncoding elements (CNEs) have been tested for regulatory activity. In the PRS locus ∼1.2–1.5 Mb upstream of SOX9, two enhancers capable of driving reporter gene expression in the embryonic mandible have been reported, consistent with their loss, and consequent disruption of SOX9 expression in the mandible, being causal in PRS patients with deletions or translocations of this region [Benko et al., 2009]. Within this PRS locus there exist at least 14 elements conserved between human and chicken, the regulatory potential of which has not been tested. Also, reporter studies have demonstrated that some craniofacial enhancers exist much closer to SOX9 [Wunderle et al., 1998; Bagheri-Fam et al., 2006; Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Mead et al., 2013]; restricted disruption of these elements could theoretically lead to craniofacial phenotypes similar to those associated with the lesions far upstream.

Here, we screened patients with nonsyndromic PRS for microdeletions at the SOX9 locus in order to highlight noncoding regions that may harbor novel craniofacial regulatory elements. We combined this with a global analysis of chromatin marks at the Sox9 locus in mouse embryonic craniofacial tissue. Our findings suggest that appropriate expression of SOX9 during craniofacial development is achieved via the action of multiple discrete regulatory elements.

Materials and Methods

Comparative Genomic Hybridization

The PRS183 deletion was identified using a custom-designed oligonucleotide microarray (Agilent Technologies) consisting of 44,000 60-mer oligonucleotide probes (eArray; Agilent Technologies). The design included the following genomic regions (hg19): FBN2 (MIM #612570) (chr5:125,172,101–128,172,101), SOX9 (chr17:67,988,405–71,988,405), SATB2 (MIM #608148) (chr2:198,591,755–201,191,755), TBX1 (MIM #602054) (chr22:19,720,000–19,820,000), and TBX22 (MIM #300307) (chrX:78,613,344–79,963,344) with an average probe spacing of 260 bp. “Dye-swap” experiments were performed for each patient sample to reduce the variation related to labeling and hybridization efficiencies. Briefly, 1 μg of genomic DNA from the patient and the control (pool of five samples) was digested with AluI and RsaI enzymes, and the digested DNA was labeled with Cyanine 3-dUTP or Cyanine 5-dUTP in dye-swap reactions, followed by hybridization, as per the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies). Slides were scanned using an Axon GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices). Images were extracted and normalized using the linear-and-Lowess normalization module implemented in the Feature Extraction software (Agilent Technologies). An R-script was used to correct for systematic differences in probe efficiencies seen on a particular array using the “self-self” microarray data [T. Fitzgerald, personal communication]. The GC bias (or wave profile) was also corrected using a 500 bp window around each probe [Marioni et al., 2007]. Copy number analysis was carried out with DNA Analytics software (Agilent Technologies) using the aberration detection module (ADM)-2 algorithm [Lipson et al., 2006] with a threshold of six and at least five consecutive probes showing a change in the copy number.

Nineteen nonsyndromic PRS patients were screened for copy number variants at the SOX9 locus using a NimbleGen fine-tiling custom array covering chr17:37,612,234–73,596,758 (these and all coordinates herein refer to assembly hg19), with a mean probe spacing of 37 bp (used for the identification of the PRS116 deletion). (Note that different custom-designed CGH arrays were used for screening case PRS183 versus the subsequent 19 nonsyndromic PRS patients because each microarray was designed independently by the FitzPatrick and Lyonnet labs, respectively).

Approval for human genetic research was obtained from the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France II.

Genomic qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was used to assess the presence or absence of the upstream SOX9 deletion in family PRS183. Reactions were carried out in triplicate and consisted of 10 ng of genomic DNA, 1 μM of each of the forward (TCTCCCAGGAGATCTTTCAATG) and reverse (GCAGCTGCGAGCCATTAT) primers, 5 μl of 2X TaqMan™ Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 μl of 20X VIC-labeled RNaseP internal control (Applied Biosystems), 0.1 μM of FAM-labeled Universal Probe Library (UPL) probe 59 (Roche Diagnostics), and 0.5 μl of PCR-grade water. Amplification and real-time data collection were performed on an HT7900 instrument (Applied Biosystems) using the following conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min. After completion of PCR, fluorescence was read using the software SDS (Applied Biosystems) and the resulting Ct values were exported and DNA copy number determined.

Sequencing

Purification of genomic DNA from lymphocytes and Sanger sequencing were performed following standard protocols. Sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing of the FOXC2 (MIM #602402) coding region and the family F1 and PRS116 deletion breakpoints are available upon request. The FOXC2 variant identified in family F2 has been submitted to a relevant locus-specific database (http://www.lovd.nl/FOXC2).

ChIP-Seq, Mouse Transgenesis, and Optical Projection Tomography

ChIP-Seq analysis of genomic regions immunoprecipitated by an anti-p300 antibody from E11.5 mouse craniofacial tissue (including nasal, maxillary, and mandibular prominences), generation of transient transgenic mice and optical projection tomography (OPT) imaging were performed as previously described [Attanasio et al., 2013]. Primers used for amplification of elements tested in transgenic reporter mice are available on request (element coordinates are listed in Table 1). Transgenic reporter data described herein will be available for viewing via the Vista Enhancer Browser at enhancer.lbl.gov [Visel et al., 2007] and FaceBase at www.facebase.org [Hochheiser et al., 2011]. The E11.5 craniofacial H3K27ac ChIP-Seq dataset was generated using similar techniques as for that of the p300 data, and will be presented in greater detail elsewhere (C.A., L.A.P., and A.V., unpublished data). Details regarding the E13.5 palatal tissue p300 ChIP-Seq data can be obtained at the FaceBase Website; see https://www.facebase.org/content/chip-seq-analysis-p300-bound-regions-e135-mouse-palates.

| cis-Regulatory elementa | Coordinates (hg19)b | Coordinates of regions used for mouse transgenic assay constructs (mm9) | Vista Enhancer Browser IDc | Craniofacial enhancer activity in vivo at E11.5 (number embryos with activity/total embryos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E11.5 p300 peak 15 | chr17:68,657,930–68,658,587 | chr11:111,424,415–111,425,316 | mm627 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 16 | chr17:68,670,660–68,671,244 | chr11:111,429,837–111,430,753 | mm628 | Positive (4/8)d |

| E11.5 p300 peak 17 | chr17:68,734,773–68,735,865 | chr11:111,488,426–111,489,423 | mm629 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 18 | chr17:68,757,543–68,758,311 | chr11:111,508,642–111,510,310 | mm630 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 19 | chr17:68,772,358–68,773,236 | chr11:111,527,366–111,528,791 | mm631 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 20 | chr17:68,930,291–68,930,938 | chr11:111,642,336–111,643,268 | mm632 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 21 | chr17:69,177,260–69,178,008 | chr11:111,822,417–111,824,278 | mm633 | No activity |

| E11.5 p300 peak 22 | chr17:69,705,542–69,709,331 | chr11:112,273,180–112,274,981 | mm634 | Positive (5/10)d |

| E11.5 p300 peak 23 | chr17:70,115,368–70,115,821 | chr11:112,641,566–112,642,353 | mm635 | Positive (5/13)e |

| E11.5 p300 peak 24 | chr17:70,371,357–70,373,428 | chr11:112,874,476–112,876,828 | mm636 | Positive (3/9)f |

| E11.5 H3K27ac peak 4 | chr17:69,696,698–69,697,764 | – | ||

| E11.5 H3K27ac peak 5 | chr17:70,116,597–70,119,020 | – | ||

| E13.5 palate p300 peak 1 | chr17:68,657,258–68,657,319 | – | ||

| E13.5 palate p300 peak 3 | chr17:68,976,805–68,976,929 | – | ||

| E13.5 palate p300 peak 4 | chr17:69,972,382–69,972,452 | – | ||

| hoc CNE-A | chr17:68,698,451–68,699,247 | – | ||

| hoc CNE-B | chr17:68,731,019–68,731,632 | – | ||

| hoc CNE-C | chr17:68,735,308–68,735,624 | – | ||

| hoc CNE-D | chr17:68,747,112–68,747,577 | – |

- a Craniofacial (or palate, as indicated) ChIP-Seq peaks and/or conserved elements. In the latter case, elements are labeled hoc CNE-A to -D. hoc indicates human-opossum-chicken CNEs in the F1-PRS183 deletion overlap region. Note that hoc CNE-C falls within E11.5 p300 peak 17.

- b The LiftOver tool at the UCSC genome browser was used for conversion of ChIP-Seq peak coordinates from mm9 to hg19.

- c Element identity available for viewing via the Vista Enhancer Browser at enhancer.lbl.gov.

- d Reporter expression in the mandible.

- e Reporter expression in the lower lip.

- f Reporter expression in the lateral nasal prominence.

Zebrafish Transgenesis

Stable lines of transgenic zebrafish were generated and analyzed following methods described elsewhere [Bhatia et al., in preparation and Ravi et al., 2013]. Briefly, the primers attB4-CACTTGATGAATTTCGGCA, attB1r-CAATTACATTTCATACTGGAG, and attB1r-CAGTTACATTTCATACTGGAG were used for amplification of wildtype and variant versions of HCNE-F2 from control and patient genomic DNA respectively. Fragments were cloned into a P4P1r entry vector before being recombined with a pDONR221 construct containing either a gata2 promoter-eGFP-polyA or a gata2 promoter mCherry-polyA cassette into a destination vector with a Gateway R4-R2 cassette flanked by Tol2 recombination sites. The peak 17 fragment was cloned into the gata2 promoter-eGFP-pA reporter construct according to the same strategy using primers attB4-GCCCTCCTGAGGAAGAGTG and attB1r-CATAATGACAGTGACCAGTG.

Immunofluorescence

Cryosections of paraformaldehyde-fixed wildtype mouse embryos were processed by standard techniques for Sox9 immunofluorescence. Primary antibody: rabbit polyclonal anti-Sox9 (AB5535; Chemicon). Secondary antibody: Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit (A31572; Invitrogen).

Results

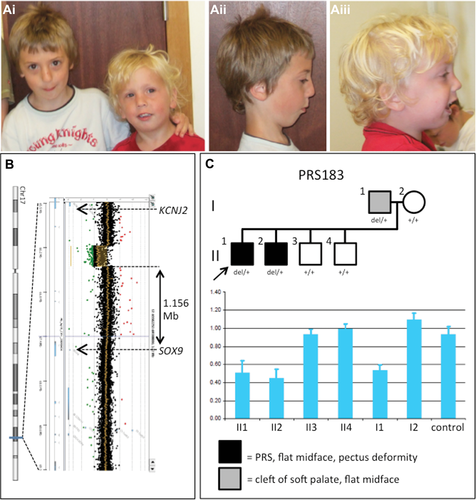

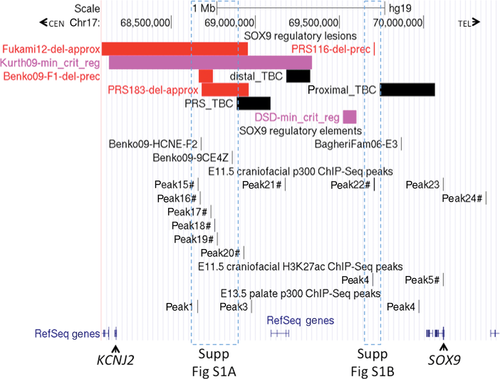

As a means to identify novel SOX9 craniofacial regulatory regions, we screened 20 patients with nonsyndromic PRS for microdeletions at the SOX9 locus using custom-designed fine-tiling CGH arrays. In one familial case (PRS183), the proband presented with cleft palate, micrognathia, crowded teeth, flat facial features, and marked pectus deformity (Fig. 1A). X-rays showed hypoplastic clavicles. His brother also had cleft palate, micrognathia, flat facial appearance, and mild pectus, whereas his father had a cleft soft palate and a flat midface. The oral abnormalities in both boys impacted on early feeding, causing failure to thrive. In the PRS183 proband, we identified a deletion of 280 kb at 1,156 kb upstream of the SOX9 transcription start site (maximum deletion coordinates, Hg19: chr17:68,680,882–68,965,323; minimum deletion coordinates: chr17:68,681,261–68,960,704), and genomic qPCR demonstrated segregation of the deletion with affected family members (Fig. 1B and C). (We note that although a high-density custom array was used to identify this deletion, the deletion is large enough that it would likely have been detected using a number of commercially available microarray platforms.) The telomeric boundary of the deletion falls within the PRS TBC, whereas the centromeric boundary falls within the F1 deletion of Benko et al. (2009) (Fig. 2 and Supp. Fig. S1A).

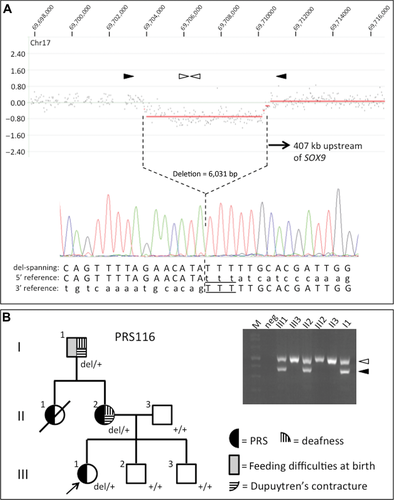

Screening of 19 additional nonsyndromic PRS patients by high-density custom CGH led to the identification of two CNVs not listed in the Database of Genomic Variants, in the region surrounding SOX9. Firstly, in the female proband of a familial case of isolated PRS (her sister also presented with PRS), a 6.78 kb duplication was identified within an intron of SLC39A11, the next coding gene telomeric to SOX9. The duplicated region is 563 kb downstream of the SOX9 transcription start site. However, a duplication junction-spanning PCR product used to genotype other family members indicated that the duplication was inherited from the proband's unaffected mother, and was not present in her affected sister (data not shown), suggesting that the duplication was not a major pathogenic factor, and the case was not considered further. The other novel CNV consisted of a 6 kb deletion 407 kb upstream of SOX9 in the proband of family PRS116 (Fig. 3A). This patient presented with isolated PRS. PRS was also present in her mother and maternal aunt (the latter died of asphyxiation three days after birth), whereas her maternal grandfather had feeding difficulties in the neonatal period, without PRS (Fig. 3B). The proband's mother and maternal grandfather also had adult-onset hearing loss and Dupuytren's contracture (MIM #126900). No radiographic anomalies were detected in the proband. The mother had supernumerary digital folds without radiographic anomalies of the hands. The deletion was verified in the proband by amplification and sequencing of a breakpoint-spanning PCR product (Fig. 3A; chr17:69,704,137–69,710,167 deleted, inclusive). A three basepair region of microhomology was identified at the 5′ and 3′ breakpoints (sequence TTT); microhomology of this size is a frequent signature of CNV breakpoints [Hastings et al., 2009; Conrad et al., 2010]. Using the breakpoint-spanning PCR product to genotype the family, the deletion was present in the proband and her affected mother and grandfather, but not in her healthy father and brothers (Fig. 3B). The deletion falls much closer to SOX9 than the previously described PRS cases and does not contain any previously reported regulatory elements, but harbors a single CNE conserved from humans to nonmammalian vertebrates (Fig. 2 and Supp. Fig. S1B).

The size of the deletion in the PRS family F1 was previously reported as ∼75 kb, at ∼1.38 Mb upstream of SOX9 [Benko et al., 2009]. As depicted in Supp. Fig. S1A, the F1 and PRS183 deletions are partly overlapping, suggesting that important craniofacial regulatory elements may fall within this region of overlap. In order to more precisely define the extent of overlap, and the CNEs that this region contains, we amplified and sequenced a deletion-spanning PCR product from genomic DNA of one affected individual from the F1 family. This analysis indicated a deletion of 84 kb (chr17:68,663,923–68,748,011 inclusive; Hg19), accompanied by an insertion of 9 bp (Supp. Fig. S2). The region of overlap between the F1 and PRS183 deletions (67 kb) contains four CNEs displaying conservation of at least 70% over 300 bp between human and each of opossum and chicken (selected at the ECR Browser; http://ecrbrowser.dcode.org/) (Supp. Fig. S1A and Table 1). Although two previously reported craniofacial enhancers, HCNE-F2 and 9CE4Z, lie centromeric to the PRS TBC [Benko et al., 2009], neither falls within the F1-PRS183 overlap (Supp. Fig. S1A). (Despite several attempts, we were unable to amplify a PRS183 deletion-spanning PCR product; therefore, the precise boundaries of the PRS183 deletion were not mapped. However, more than 10 nondeleted CGH probes fell between HCNE-F2 and the first deleted probe of the PRS183 deletion interval (a region of approximately 5 kb), indicating that HCNE-F2 falls outside the PRS183 deletion and hence outside the F1-PRS183 overlap.) This suggests that other craniofacial regulatory elements may exist within the F1-PRS183 deletion overlap.

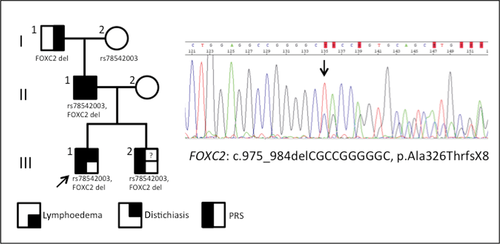

The HCNE-F2 element was previously investigated because it harbors a single base variant in several affected individuals of a PRS family [family F2 in Benko et al., 2009]. HCNE-F2 is not conserved outside placental mammals, and was the only CNE within the F1 deletion that was tested for regulatory activity [Benko et al., 2009]. Subsequent to that report, we identified features suggestive of lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome (LDS; MIM #153400) in several members of the F2 family (Fig. 4). Sequencing of the coding region of the major candidate gene for LDS, FOXC2, revealed a 10 bp deletion, leading to a frameshift and a premature stop (RefSeq transcript NM_005251.2:c.975_984delCGCCGGGGGC, p.Ala326ThrfsX8), in the proband, his brother and his father, each of whom have PRS, and in the paternal grandfather who does not have PRS (Fig. 4). The proband and his brother have not yet developed lymphedema. PRS or cleft palate has been reported in a proportion of LDS patients harboring FOXC2 mutations [Fang et al., 2000; Erickson et al., 2001; Finegold et al., 2001; Bahuau et al., 2002; Brice et al., 2002; Tanpaiboon et al., 2010], and Foxc2 homozygous null mice display mandibular dysplasia and cleft palate [Iida et al., 1997; Winnier et al., 1997]. The single base change in HCNE-F2 was inherited from the paternal grandmother, who did not present with PRS [Benko et al., 2009]; therefore, the three members of this family with PRS are the only three with both the FOXC2 mutation and the HCNE-F2 variant, suggesting that both these events may have contributed to the PRS phenotype. Although the variant was initially not detected in a group of control patients [Benko et al., 2009], the same base change has recently been reported as a SNP (rs78542003, T>C), with a C allele frequency of 1.433% (33 counts/2302 alleles) (from UCSC data last updated 2012–11–09). Previous in vitro assays suggested that the variant sequence modified the binding of MSX1 (MIM #142983), a transcriptional regulator with essential roles during craniofacial development. To support the argument that the HCNE-F2 variant can alter enhancer activity in vivo, we performed transgenic analysis in zebrafish embryos, testing the ability of the wildtype and variant versions of the enhancer to drive mCherry or GFP reporter expression, respectively, in four independent stable lines (each line harboring both transgenes). We found that wildtype HCNE-F2 could drive expression in the developing pharyngeal arches and craniofacial cartilage (but not Meckel's cartilage), whereas this activity was decreased or lost for the version harboring the variant (representative images are shown in Supp. Fig. S3). Collectively these results suggest that the HCNE-F2 variant is likely to play a less important role in the pathogenesis of PRS than previously suspected, however it remains possible that it may contribute to the phenotype by acting as a modifying allele in the presence of the FOXC2 coding mutation.

We also conducted a genome-wide analysis of craniofacial cis-regulatory activity, by performing ChIP-Seq for p300- or acetylated H3K27 (H3K27ac)-associated genomic elements in E11.5 mouse craniofacial tissue and p300-associated elements in E13.5 mouse palatal tissue. H3K27ac and p300 chromatin marks have been used previously as predictors of developmental enhancers [Visel et al., 2009; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011]. We focused on p300 and H3K27ac binding events (peaks) within a ∼3 Mb interval encompassing Sox9. Following conversion from mouse to human coordinates (where possible), we compared the distribution of peaks with genomic lesions associated with PRS in previous studies and the present report, with the hypothesis that the peaks represent elements involved in the normal expression of SOX9 during early craniofacial development, and that their loss could contribute to the PRS phenotype. Nine E11.5 p300 peaks were identified in the 1.9 Mb interval between KCNJ2 (MIM #600681) and SOX9, and one fell within a 1 Mb region downstream of SOX9 (Fig. 2). Apart from peak23, which falls on a portion of the SOX9 proximal promoter, all eight other peaks in the KCNJ2–SOX9 interval overlapped a CNE with conservation between human and chicken (according to the Multiz alignment track in the UCSC browser), supporting the functional relevance of these peaks. Importantly, five of these eight peaks (peaks 15–19) were clustered in a domain of 115 kb, proximal to the PRS TBC (Fig. 2 and Supp. Fig. S1A). Peak22 falls within the 6 kb deletion identified in PRS116 (Supp. Fig. S1B); this is particularly striking considering that it is the only p300 peak within a 0.9 Mb interval upstream of the SOX9 proximal promoter (Fig. 2). Two peaks from the E11.5 craniofacial H3K27ac and three from the E13.5 palatal p300 ChIP-Seq studies fell in the KCNJ2–SOX9 interval (Fig. 2, Supp. Fig. S1A and S1B); several of these were also either within or adjacent to regions deleted in PRS patients.

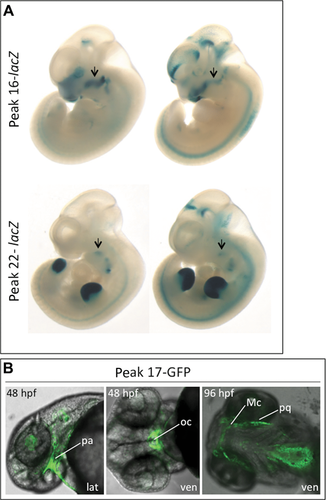

For each of the 10 E11.5 p300 peaks, in vivo reporter activity was tested in transient transgenic mouse assays at E11.5, using constructs harboring a given peak region upstream of lacZ (genomic coordinates of the regions used and a summary of in vivo craniofacial reporter activity are listed in Table 1). Two peaks demonstrated lacZ expression in mandibular mesenchyme (peaks 16 and 22; Fig. 5A and Supp. Fig. S4). Peak 16 drove expression in the proximal first arch in 4/8 embryos (Fig. 5A, upper row), and peak 22 drove relatively weak but reproducible expression in a specific region of the mandible (5/10 embryos; Fig. 5A, lower row). Examination of OPT slices from peak 16- and peak 22-lacZ embryos indicated an overlap of lacZ expression with a portion of the endogenous Sox9 protein expression domain in the mandible (Supp. Fig. S4 and see Supp. Movies S1 and S2). Peak 23 drove reporter expression in the lower lip in 5/13 embryos and peak 24 drove expression in the lateral nasal prominence in 3/9 embryos. Peak 22-lacZ also displayed strong relative staining in distal limb bud mesenchyme (9/10 embryos; Fig. 5A, lower row and Supp. Fig. S4E). Peak 24 drove expression in an anterior domain of the limb bud in 6/9 embryos and peak 15-lacZ showed staining in a specific region of the limb bud in 6/11 embryos (data not shown).

The only E11.5 p300 peak falling within the minimal region of overlap between the F1 and PRS183 deletions is peak 17. This peak covers one of the four human-opossum-chicken CNEs in this minimal region of overlap. However, the peak 17 region displayed no reproducible lacZ reporter activity in transient transgenic mice at E11.5. Given the potential importance of this element, we tested its activity in a different model. We generated four independent lines of zebrafish stably expressing a peak 17-GFP reporter gene. We observed consistent expression of GFP in the region surrounding the oral cavity at 48 hpf and in first branchial arch-derived cartilages, including Meckel's, at 96 hpf (Fig. 5B), supporting the idea that peak 17 functions as a craniofacial regulatory element.

Discussion

In this report, we have identified two novel deletions upstream of SOX9 in PRS patients, one of which (in family PRS183) partly overlaps a previously described deletion associated with isolated PRS, and the other (in family PRS116) falling in a region much closer to SOX9, not previously associated with PRS. These deletions contain or fall in close proximity to novel candidate craniofacial enhancers of SOX9, identified here by ChIP-Seq and validated in transgenic reporter assays. For each deletion, PRS was associated with other phenotypes. In the PRS183 family, other features included pectus deformity and flat midface (we note however that several features in this family displayed variable expression, with the two deletion-positive siblings more severely affected than their father). Although thorax abnormalities are common in CD, pectus deformities are not frequently reported. However, pectus was described in several members of a family affected with ACD [Stalker and Zori, 1997] and harboring a translocation breakpoint 932 kb upstream of SOX9 [Hill-Harfe et al., 2005]. The 280 kb deletion in family PRS183 falls 224 kb further proximal to this breakpoint, suggesting that both cases involve the disruption of regulatory elements that direct appropriate expression of SOX9 during thoracic skeletal development. In addition to family PRS183, a flattened face was mentioned in two PRS cases harboring balanced translocations within the PRS TBC [Jakobsen et al., 2007; Vintiner et al., 1991; Benko et al., 2009]. A flat face being a typical feature of CD, nonmandibular craniofacial enhancers of SOX9 may also exist proximal to the PRS TBC. A 3 Mb deletion upstream of SOX9 was recently reported in a patient with PRS, scapula hypoplasia and clubfeet [Fukami et al., 2012]; in this case, the telomeric breakpoint boundary also fell within the PRS TBC (see Fig. 2). It has been reported that a ∼2.4 Mb region centered on Sox9 undergoes chromatin decompaction in the embryonic mouse mandible [Benko et al., 2009] and that SOX9 co-localizes with a region 1.1 Mb upstream in human interphase nuclei [Velagaleti et al., 2005]. In the Odd Sex mouse mutant, a transgene insertion influences expression from almost 1 Mb upstream of Sox9 [Qin et al., 2004]. Recently, it has been demonstrated by chromatin conformation capture that an element 1 Mb upstream loops to the SOX9 promoter in a prostate cancer cell line [Zhang et al., 2012], while chromosome conformation capture-on-chip analysis identified interactions between the SOX9 promoter and regions ∼1.13 Mb and ∼967 kb upstream in Sertoli cells and lymphoblasts [Smyk et al., 2013]. The above data support the idea that SOX9 can be regulated by a region further than 1 Mb upstream, but that this region is not solely involved in mandibular SOX9 expression. In family PRS116, two individuals harboring the deletion had Dupuytren's contracture, a fibrotic connective tissue disorder that to our knowledge has not previously been described in the context of SOX9-related disease. The relevance of this phenotype to the deletion remains unclear; however, it is worth noting that SOX9 has been implicated in various fibrotic pathologies, where it may regulate extracellular matrix deposition [Pritchett et al., 2011]. The same two PRS116 individuals also had late-onset deafness, which is intriguing given the role of Sox9 in mice in both ossicular and otic vesicle development [Mori-Akiyama et al., 2003; Barrionuevo et al., 2008]. Further analysis of peak 22-lacZ transgenic mice at multiple stages of development will be required to determine whether this element can drive expression in the ear.

Our ChIP-Seq analysis of regions binding p300 in the KCNJ2–SOX9 interval led to the identification of several novel candidate enhancers of SOX9 expression. Transgenic analysis in mice and zebrafish demonstrated that peaks 16, 17, and 22 can drive reporter expression within the developing mandible, consistent with their loss playing a role in the pathogenesis of PRS in patients harboring deletions of these elements. The PRS183 deletion reported here does not include the previously identified craniofacial enhancer HCNE-F2 [Benko et al., 2009], whereas the family F1 deletion [Benko et al., 2009] did not include the 9CE4Z enhancer. Therefore, the region of overlap between the PRS183 and F1 deletions (67 kb) may harbor other craniofacial SOX9 enhancers—indeed, the region contains four CNEs conserved from human to chicken. Notably, peak 17, which displayed craniofacial regulatory activity in zebrafish, falls on one of these four CNEs. Although peak 22 drove reproducible but relatively weak expression in the E11.5 mandible, it was strongly active in the distal limb bud at this stage—no previously reported SOX9 enhancer shows this degree of specificity within the developing limb, and it will be of interest to explore the expression pattern of peak 22-lacZ (along with the other limb bud-active peaks identified here; peaks 15 and 24) at later stages of chondrogenic development. No single enhancer thus far identified at the SOX9 locus drives expression specifically in all chondrogenic tissue. It is possible that SOX9 expression in developing cartilage is achieved by the action of many regulatory elements, each providing maximal activity in small subdomains. Interestingly, of the two H3K27ac craniofacial peaks within the 1.9 Mb KCNJ2–SOX9 interval, one falls 8 kb away from p300 peak 22, which displayed in vivo reporter activity and falls within the PRS116 deletion. (Note the only other H3K27ac peak falls on the SOX9 proximal promoter.) Further upstream, p300 craniofacial peaks 15–19, p300 palate peak 1, HCNE-F2 and 9CE4Z all fall within a 210 kb interval proximal to the PRS TBC; note that none of these eight elements are overlapping, suggesting that many individual inputs may contribute to the craniofacial regulatory activity of the region. In addition, previous studies showed craniofacial regulatory activity closer to SOX9 [Wunderle et al., 1998; Bagheri-Fam et al., 2006; Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Mead et al., 2013], and the peak 22 craniofacial enhancer identified here in the PRS116 deletion falls at 408 kb upstream. A major question is how these dispersed activities are coordinated with respect to each other and to enhancers for other cell types.

In conclusion, we have identified novel PRS-associated deletions upstream of SOX9, and we have utilized p300 ChIP-Seq and in vivo reporter assays to define novel craniofacial regulatory elements falling within these or previously reported deletions. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that these elements are required for appropriate expression of SOX9 during craniofacial development, and that their loss contributes to the PRS phenotype.

Acknowledgments

C.T.G., J.A., and S.L. were supported by funding from the ANR grants EvoDevoMut, CRANIRARE, and IHU-2010–001. T.Y.T. was supported by a NHMRC Training Fellowship (#607431). A.V. and L.A.P. were supported by NIH grants R01HG003988 and U01DE020060. C.A. was supported by a SNSF advanced researchers fellowship. Research by A.V., L.A.P., and C.A. was conducted at the E.O. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and performed under Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02–05CH11231, University of California.

Disclosure statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.