(Mid)West Side Story: Acute Hepatitis C Virus Infection and the Opioid Epidemic in the United States

In the February 2018 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, Zibbell et al. report on a relationship between increases in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections and the rising opioid injection epidemic in the United States. The authors base their report on acute HCV case data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) and national substance use disorder (SUD) admissions data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Treatment Episode Data Set: Admissions (TEDS-A).1 The current publication is a nationwide follow-up analysis of a central Appalachia four-state analysis that identified a dual epidemic of acute HCV infections and increases in SUD treatment admissions among people with opioid use disorders.2

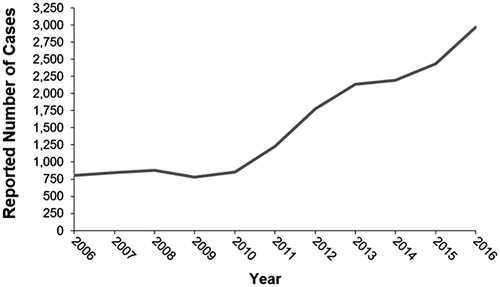

As a result of the overly generous prescribing of opioid pain relievers that started in the late 1990s, a significant number of people living in the United States have become addicted to prescription opioid analgesics (POAs) and subsequently to heroine and other opioids as well as nonopioid drugs—most often administered intravenously. This has led to a deplorable number of more than 115 people dying of an opioid overdose every day in the United States, according to the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse.3 Other consequences of intravenous drug use (IDU) include transmission of viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus and HCV through the reuse of contaminated drug paraphernalia (e.g., needles, syringes, cookers, and filters). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a total of 2,967 cases of acute HCV were reported from 42 states in 20164 (Fig. 1). The overall incidence rate for 2016 was 1.0 case per 100,000 people, an increase from 2015 of 0.8 case per 100,000 people. Actual acute cases are estimated to be 13.9 times the number of reported cases in any year. In addition, recent research has reported that the U.S. opioid epidemic is moving away from metropolitan centers, potentially fueling the acute HCV epidemic, because access to syringe service programs and medication-assisted therapy for opioid addiction is far more limited in rural settings.5

Zibbell et al.’s analysis is both timely and informative because it establishes a connection between increasing acute HCV cases and the ongoing opioid injection epidemic on a national level. The authors’ data come with the usual caveats when interpreting retrospective cohort data. For one thing, only data that have been reported can be analyzed, which may have led to an underreporting of cases of both acute HCV infection in the NNDSS and SUD treatment admissions in TEDS. Up until 2012, diagnosis of acute HCV infection was based solely on clinical signs or elevated liver enzymes. Because it is frequently asymptomatic or presents with rather unspecific clinical signs, and because most people who inject drugs (PWID) do not regularly see a physician for blood checks, a substantial number of acute HCV cases might not have been diagnosed and therefore not reported. It was not until 2012 that, following a modified surveillance case definition, cases with a documented negative HCV antibody test result followed by a positive result within 6 months were also reported. With regard to SUD treatment admissions, only 67% of these admissions are estimated to be included in TEDS—potentially missing out on the ones at most risk and with minimal access to health care services. This double underreporting bias implies that the actual situation might even be more serious than described by the authors. On the other hand, the authors fail to acknowledge that rates of spontaneous clearance of acute HCV in PWID have been reported to be up to 40%; i.e., not every acute HCV infection leads to a chronic illness.6

Zibbell et al. saw the largest increases (>100% from 2004 to 2014) in acute HCV infections among persons aged 18 to 29 years and 30 to 39 years and among non-Hispanic white and Hispanic persons, all of which were statistically significant. Over the 11-year observation period, IDU was reported in 60% or more of cases that included risk factor data. Between 2011 and 2014, this rose to 75%, and in 2014, it reached 84%.

With the Midwest hit hardest by the opioid epidemic, the authors fittingly observed the highest increases in acute HCV infections (>1,000% from 2004 to 2014) here and in three other states: Kansas, Maine, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Massachusetts.

In terms of TEDS admissions attributed to IDU, the authors saw an increase of 76% over the 11-year observation period. Heroine injection increased significantly (P < 0.001), and injection of POAs increased by 258%, clearly identifying the source of the acute HCV epidemic.

The authors also detected gender differences, with rates of acute HCV infection increasing almost 4-fold among women and more than 2-fold among men over the 11-year period. The increase in women falls in line with reports of increases in infants being born to HCV-positive mothers and/or suffering from neonatal abstinence syndrome, in addition to possibly losing their mothers because of an overdose. It is this part of the authors’ analysis that turns the linkage between acute HCV cases and opioid injection into a modern-day medical emergency.

In light of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s national strategy for the elimination of hepatitis B and C, along with the availability of well-known and proven prevention measures (e.g., needle-exchange programs and opioid substitution therapy) and extremely effective HCV therapies, the report by Zibbell et al. is a serious public health wake-up call to the medical community that we can and must do better.