Quality of life and primary sclerosing cholangitis: The business of defining what counts

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by the National Institute for Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham (K.A, G.M.H.).

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Abbreviations

-

- IBD

-

- inflammatory bowel disease

-

- PROM

-

- patient-reported outcome measure

-

- PSC

-

- primary sclerosing cholangitis

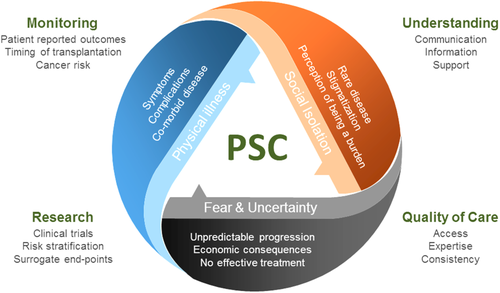

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is the rare chronic liver disease par excellence for which clinicians and patients alike seek better treatments, principally interventions that reduce the need for liver transplantation and that materially change the devastating natural history of symptomatic cholangitis, end-stage liver failure, and unpredictable malignancy. This goal is complicated by a complex, heterogeneous etiopathogenesis and clinical course, characterized by facets of disease that are autoimmune, cholestatic, inflammatory, profibrotic, premalignant, and associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1, 2 PSC is symptomatic in the majority and, above all for individuals living with this disease, provokes anxiety in patients, family, and carers. When asked, patients will readily volunteer the impact of pain, itch, fatigue, and uncertainty.3, 4 One online survey run by PSC Support (www.pscsupport.org.uk) involving over 1,000 respondents found that the most difficult thing for patients about living with PSC was the impact on their emotional well-being (cited by 74% of respondents), with specific concerns including uncertainty about the future, helplessness, and concern about their medical care and monitoring.

In parallel to the pursuit of therapies that slow down the inflammatory and profibrotic pathways associated with a relentless cholangiocyte injury, there is a paramount need for improvement to outcomes that therefore equally addresses an individual's quality, as well as quantity, of life (Fig. 1). In what is a difficult clinical trials arena, discussions continue about what is an appropriate efficacy endpoint at different stages of a product's development.5 One key consensus has been the need for future trial opportunities to place greater emphasis on patient-reported outcomes that include, in particular, the participant's quality of life. At the present time, dedicated tools that can reproducibly measure such an important vector within the disease trajectory are not available consistently and certainly are not PSC-specific. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) assess not only physical symptoms but also mental and social well-being, overall providing data as to the real impact of disease on patients' everyday lives. Disease-specific PROMs are felt to be more informative in delineating domains more specific to one particular disease, allowing for more patient-centered assessment.

In this issue of Hepatology, Younossi et al. describe the development of a new PSC-specific PROM instrument.6 This work, an important partner to a trial program, is worthy of comment because, albeit not complete, it marks a transition point for the community. The instrument was initially developed using qualitative interviewing of participants with PSC; a draft was drawn up after the first 20 interviews, and it was then validated by a further 26 independent participant interviews. While the numbers are small, this is standard practice for qualitative research methodology, where the number of interviews is often aimed at around 15-25; for a disease heterogeneous in its very core, validation of this approach will, however, be important in PSC. Once relevant changes had been made to the PROM instrument throughout, the final design contained 42 questions divided into two modules; the first describes symptom severity, and the second describes the impact of the disease. The “impact of disease” module includes domains such as physical function, work productivity, role function, emotional impact, and quality of life. The finalized PROM was then validated in 102 external participants with PSC along with four other commonly used PROM instruments: Short Form-36, Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire, PBC-40, and 5D-itch. Fifty-three participants with PSC who were assessed as clinically stable then repeated the instrument again within 3 months to assess for consistency.

Globally the authors report patient satisfaction with the instrument, and consistency was found with repeated measurements, in the scenario of clinical stability. There was a skewed distribution of domain scores toward the lower values, suggesting better health status or possibly a “floor” effect. Significant correlations were seen with the other PROM instruments; this correlation was seen less with the 5D-itch scale, and the authors reported that no correlation was >90%, indicating a role for a PSC-specific instrument.

This study equally illustrates limitations and challenges in this area. The population evaluated is clearly small, and the repeated measurements were completed in short succession. One third of the external validation cohort was male, with considerably higher scores in multiple domains. This is rather a lower sex ratio than is traditionally recognized for PSC, and thus, the application of the tool in the wider PSC population is going to be important. How the tool will fare in diverse settings with varying participant backgrounds will be a key aspect of its development. It is also unclear what effect “survey fatigue” may have had on patients who were completing five separate instruments concurrently or how feasible a 7-15-minute instrument may be in differing clinical settings. A further limitation raised by the authors is that the role of comorbid IBD could not be delineated with this instrument, meaning an IBD-specific PROM is also required. This is significant as there is established evidence as to IBD being a major determinant of quality of life in PSC, and given the close association between diseases and potential therapies, accurate recognition of the role of concomitant IBD in a participant's quality of life is important.

Beyond drug therapy, it is also likely that “how” we care for patients has important impacts on their experiences, in addition to disease-specific medical management itself. Within the management of this complex rare disease and its impact upon patients must equally be layered the structural/logistic health care delivery issues that vary globally; these issues are also contributors (and opportunities) to ultimate patient experience and overall quality of life. It is also worth considering how use of disease-specific PROM tools could be used to improve routine care for patients; e.g., serial monitoring of PROM tool outputs for a patient could be used to trigger clinical review and investigations in a more targeted response-driven approach to care.

While the authors acknowledge that this PROM instrument needs further validation in a larger, multinational cohort and further assessment of the sensitivity of the instrument to clinical changes over time, the study and its outcomes are nevertheless a step forward. Once a validated disease-specific PROM instrument is embedded into practice, we will reach one step further toward obtaining varied clinically meaningful endpoints for PSC, by being able to design clinical trials tailored to produce measurable whole-patient benefit. This is a complex area, and difficulties remain as to how to delineate quality-of-life impact that is liver-specific, bowel-specific, or indeed PSC/IBD-specific. Data from PROMs will form part of a regulator's assessment of a new therapy but will always be just one aspect of evaluable data: the new therapy for primary biliary cholangitis, obeticholic acid, is the first new licenced opportunity for patients with primary biliary cholangitis, yet its close biologic properties have both positive disease impact as well as potential deleterious symptom side effects. For future therapies in PSC, similar challenges may also arise. Notwithstanding these challenges encountered by patients with PSC, there is renewed optimism that the intensity of effort being afforded to the many spinning tops PSC presents, across many domains of health, is increasingly being recognized as progress.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank PSC Support for access to their participant survey.

-

Katherine Arndtz1-3

-

Gideon M. Hirschfield1-3

-

1National Institute for Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre

-

2Institute of Immunology & Immunotherapy, University of Birmingham

-

3Centre for Rare Diseases, Institute of Translational Medicine

-

Birmingham Health Partners

-

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital

-

Birmingham, UK