Decellularized human placenta supports hepatic tissue and allows rescue in acute liver failure

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK071111 and R01-DK088561.

Abstract

Tissue engineering with scaffolds to form transplantable organs is of wide interest. Decellularized tissues have been tested for this purpose, although supplies of healthy donor tissues, vascular recellularization for perfusion, and tissue homeostasis in engineered organs pose challenges. We hypothesized that decellularized human placenta will be suitable for tissue engineering. The universal availability and unique structures of placenta for accommodating tissue, including presence of embedded vessels, were major attractions. We found decellularized placental vessels were reendothelialized by adjacent native cells and bridged vessel defects in rats. In addition, implantation of liver fragments containing all cell types successfully hepatized placenta with maintenance of albumin and urea synthesis, as well as hepatobiliary transport of 99mTc-mebrofenin, up to 3 days in vitro. After hepatized placenta containing autologous liver was transplanted into sheep, tissue units were well-perfused and self-assembled. Histological examination indicated transplanted tissue retained hepatic cord structures with characteristic hepatic organelles, such as gap junctions, and hepatic sinusoids lined by endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, and other cell types. Hepatocytes in this neo-organ expressed albumin and contained glycogen. Moreover, transplantation of hepatized placenta containing autologous tissue rescued sheep in extended partial hepatectomy-induced acute liver failure. This rescue concerned amelioration of injury and induction of regeneration in native liver. The grafted hepatized placenta was intact with healthy tissue that neither proliferated nor was otherwise altered. Conclusion: The unique anatomic structure and matrix of human placenta were effective for hepatic tissue engineering. This will advance applications ranging from biological studies, drug development, and toxicology to patient therapies. (Hepatology 2018;67:1956-1969).

Abbreviations

-

- ALF

-

- acute liver failure

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- CT

-

- computed tomography

-

- DAPI

-

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

-

- ECM

-

- extracellular matrix

-

- HBSS

-

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

-

- H&E

-

- hematoxylin and eosin

-

- KC

-

- Kupffer cell

-

- LSEC

-

- liver sinusoidal endothelial cell

-

- PBS

-

- phosphate buffered saline

-

- PH

-

- partial hepatectomy

Tissue engineering to generate organs is relevant for transplantation medicine and for basic studies. Despite advances, major challenges remain in bioartificial organs recapitulating complex structure–function relationships in tissues.1 Hepatic engineering is of major interest because of its therapeutic potential for numerous genetic and metabolic deficiencies or acquired conditions.2 For instance, treatment of serious hepatic injury or acute liver failure (ALF)3 often requires orthotopic liver transplantation, but simpler alternatives will be helpful to overcome donor organ shortages.

To survive and express functions appropriately, anchorage-dependent cells require suitable scaffolds in engineered organs.4, 5 In the liver, major hepatic functions benefit from interactions between hepatocytes and other cell types, including liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), Kupffer cells (KCs), and hepatic stellate cells.6 Hepatic organization of acini with dual systemic and portal blood supply is also central in liver biology, since this affects position-specific gene expression, mass transfer, and biliary transport.7 Whereas transplantation of hepatocytes with or without other cell types with scaffolds allows their survival over the short term,8 extracellular matrix (ECM) components in decellularized tissues offer further support.4 However, major challenges remain; for example, relining with endothelial cells of decellularized vessels to maintain patency has been problematic.1 Scaling up to large animal models for testing clinical applications has also been a hurdle. The source and state of donor organs pose other issues, because disease and post mortem effects might alter cell survival.

We hypothesized that human placenta offers outstanding opportunities for tissue engineering by serving as a suitable receptacle with multiple other advantages. For instance, healthy placentae are available universally. The placenta is endowed with vascular networks for exchanging arterial and venous blood, ample space for transplanted cells or tissues, and ECM containing beneficial factors associated with vascular, mesenchymal, parenchymal, and other cell types.9 This was eminently testable. Moreover, we considered that instead of engineering tissue by implanting one cell type or lineage at a time, which has been the usual approach, using tissue fragments containing all liver cell types at once could work.10 Here, we developed these principles to generate “hepatized placenta,” including characterization of various properties in transplanted liver tissue, followed by studies of its therapeutic potential in a large animal model (sheep), where we used autologous liver from donors for rescue in ALF. These studies established the potential of decellularized human placenta for tissue engineering.

Materials and Methods

HUMAN TISSUES

The Institutional Review Board at Tbilisi State Medical University approved tissue procurement. Informed consent was obtained. Donors were healthy with uncomplicated full-term pregnancies. Placentae were collected immediately after deliveries following standard clinical care.

ANIMALS

The Georgian National Medical Research Institute approved animal use (permit #14-48). Animals received unrestricted access to food and water. Wistar rats (n = 30) were 8-10 weeks old, weighed 200-250 g, and were obtained from the breeding facility of Tbilisi State Medical University. Ether-based anesthesia was used for rat surgery. Female sheep of a Turkish breed weighing 15-20 kg (n = 27) were obtained from a certified facility in Georgia with housing in individual pens. For anesthesia, sheep received 0.03-0.05 mg/kg atropine intramuscularly and 0.5 mg/kg diazepam intravenously followed by 20 mg/kg ketamine intravenously and 5 mg/kg xylazine intramuscularly. For analgesia, 1 mg/kg ketoprofen was given intramuscularly immediately after surgery and for 3 days subsequently. To avoid sepsis, 2 mg/kg gentamicin and ceftriaxone each were given intramuscularly twice daily for 6 days. Animals were monitored for recovery after anesthesia, normal activities, and bleeding or other complications.

TISSUE DECELLULARIZATION

The umbilical artery and veins were cannulated and cleared by irrigating normal saline containing heparin. Placentae were then stored at −80°C. For decellularization, after warming to 4°C, placentae were perfused through the artery with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) overnight, followed by 0.01%, 0.1%, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate in distilled H2O for 3 consecutive 24-hour periods, respectively, at 1 mL min−1. To remove sodium dodecyl sulfate, placentae were irrigated with distilled H2O for 30 minutes, 1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour, and PBS for 3 hours. Placentae were stored in PBS containing penicillin and streptomycin for up to 7 days at 4°C or after draining PBS indefinitely at −80°C. In some instances, placentae were lyophilized and stored at −80°C.

DNA CONTENT

Tissue DNA was extracted (G-spin Kit; iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea) and measured at 260 nm (NanoDrop 1000; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

ANATOMY OF DECELLULARIZED PLACENTA

For vascular anatomy, the placental artery and vein were cannulated and irrigated with normal saline to clear blood, and casts were obtained with 40 mL 50% latex in water (NAIRIT L-3, NAIRIT) or Minium Red oxide of lead (Pb3O4 + PbO [M−]) in turpentine oil. For angiography, radiocontrast was injected into the placental artery. For electron microscopy, samples were fixed in glutaraldehyde and dried in Tousimis Samdri-780 critical point dryer (Tousimis Research, Rockville, MD), followed by gold sputter-coating of ultrathin sections with a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

DECELLULARIZED VESSELS AND GRAFTING

Placental artery segments were irrigated with water for 12 hours and treated with heparin as described previously.11 Decellularized arteries were filled with 1% protamine sulfate under 120 mm Hg pressure, irrigated with water for 30 minutes, and soaked in 1000 U/mL heparin for 48 hours. Vessels were sterilized in PBS containing 0.1% peracetic acid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 3 hours. For mechanical strength, 2.5- to 3-cm-long vessel segments of 1.5-2.5 mm diameter were cannulated at either end with polypropylene catheters secured by 4-0 proline (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ). These segments were immersed in a normal saline bath at 37°C, and saline was pumped with increasing pressure into one end until bursting occurred. For the ability of vessels to bridge arterial defects, the common carotid artery was divided between ligatures in rats. Polyethylene cuffs with handles and a 0.7-mm outer diameter and 0.6-mm inner diameter were applied to the two ends of artery according to the method described by Zou et al.11 The edges of artery ends were everted over cuffs, and decellularized placental vessels were fixed with 9-0 sutures to the cuffs. Rats were euthanized 5, 10, 15, 30, and 40 days after surgery. Angiography used radiocontrast or fluorescein. Formalin-fixed graft sections were examined by immunostaining for desmin, α-smooth muscle actin and von Willebrand factor (Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

HARVESTING AND PROCESSING OF SHEEP LIVER AND HEPATIZATION OF DECELLULARIZED PLACENTA

The left lobe of liver (30%, typically 110-120 g) was removed after ligating its pedicle with midline laparotomy. The resected liver was irrigated through the portal vein branch with Hanks' balanced salt solution (pH 7.4). The liver was fragmented with a mechanical tissue chopper for 5-6 minutes at room temperature. This time was determined in earlier studies. Fragments >1-2 mm in size were removed by passage through two layers of surgical gauze and filtrate collected in 30 mL of Hanks' balanced salt solution. Fragment viability was determined using Trypan blue dye exclusion. Fragments were fixed in formalin for histology. For hepatization, the placenta was trimmed to size and the tissue integrity was confirmed by irrigating saline. Up to 150-mL liver fragments, 10-15 mL per cotyledon, were injected through the placenta capsule with an 18- to 20-gauge needle. Typically, the time from decellularized placenta preparation to use was <30 minutes. The hepatized placenta was tested by injecting colored latex into the vessels. For albumin secretion, RPMI 1640 medium was infused at 10 mL/min for 3 days. Aliquots of perfusate were stored daily for albumin content. For urea synthesis, 5 mM ammonium chloride was added to infusate for 1 hour, and perfusate was collected daily over this period. For hepatic transport, 3.8 mBq of 99mTc–Bromo-Billaron (Medi-Radiopharma, Budapest, Hungary) was injected into placental artery with dynamic imaging (Gamma-camera Siemens E-cam) using 20% window centered on 140 keV at 5 seconds per frame for 1 minute and 1 minute per frame for 59 minutes. Multiple regions of interest were analyzed.

HETEROTOPIC TRANSPLANTATION OF HEPATIZED PLACENTA IN SHEEP

Sheep were given 100 U heparin intravenously to decrease thrombosis. The right femoral artery and vein were partially side-clamped. The hepatized placenta was implanted subcutaneously in the ilio-inguinal space. After end-to-side anastomoses of placental and femoral arteries and veins with 6-0 proline, the graft was perfused. Vascular flow was examined using Doppler ultrasonography (Logiq7 Ultrasound Machine; GE Electronics, Tbilisi, Georgia) and computed tomography (CT) angiography (Innova-3100 Digital Cath & Angio, GE Electronics) with ULTRAVIST-300 intravenously at 3-5 mL/s to 50 mL. Arterial, venous, and renal phases were identified by established protocols.

PARTIAL HEPATECTOMY MODEL OF ALF IN SHEEP

After midline laparotomy, hepatic lobes were isolated and resected, except for portions of the anterior lobes and entire caudate lobe, to constitute 85% partial hepatectomy (PH). Hemostasis and bile leaks were secured by 5-0 sutures or fibrin (Tisseel; Baxter, Hochstadt, Germany). Hepatized placenta was transplanted after PH was completed while sheep were under anesthesia. Blood samples were collected at intervals. Animals were euthanized with intravenous pentobarbital sodium. At necropsy, liver and graft dimensions were recorded for estimating organ volume, which was converted to weight by reference liver samples containing blood from healthy sheep. Similarly, placental graft dimensions were recorded for comparisons in animal groups.

HISTOLOGICAL STUDIES

Tissues were fixed in formalin and paraffin-embedded sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson's trichrome. Glycogen was stained as described previously,12 except no counterstain was used. Lysosomal acid phosphatase staining was performed as described previously.13 For immunostaining, antigen retrieval used citrate buffer for 15 minutes and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Sections were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline for 45 minutes and incubated with anti-human antibodies for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, or von Willebrand factor (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 18 hours at 4°C followed by EnVision+ System labeled horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (DAKO) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Tissue sections were developed in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-chromogen substrate mix (DAKO) and hematoxylin counterstain. For DNA damage, sections were treated with 250 ng/mL RNAse for 1 hour at 37°C, denatured by 4 M HCl for 7 minutes with neutralization in 50 mM Tris base for 2 minutes, followed by blocking in 10% goat serum for 1 hour and incubated in 8-oxo-dG antibody overnight at room temperature (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Connexin-32 was stained by anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. Albumin was stained with polyclonal anti-rat immunoglobulin G (US Biochemical Corp, Cleveland, OH). For Ki-67, tissue sections were blocked in 5% goat serum, permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 1 hour, and incubated with anti-Ki67 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) overnight at 4°C. Detection used Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-sheep immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at room temperature with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain.

LIVER TESTS

Samples were stored for total serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, and urea. Prothrombin time was determined in fresh plasma samples. These were measured in a clinical laboratory.

STATISTICAL METHODS

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median (range) as appropriate. Statistical significances were identified using the Student t test, chi-squared test, or log-rank test. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

DECELLULARIZED HUMAN PLACENTA ALLOWED HEPATIZATION

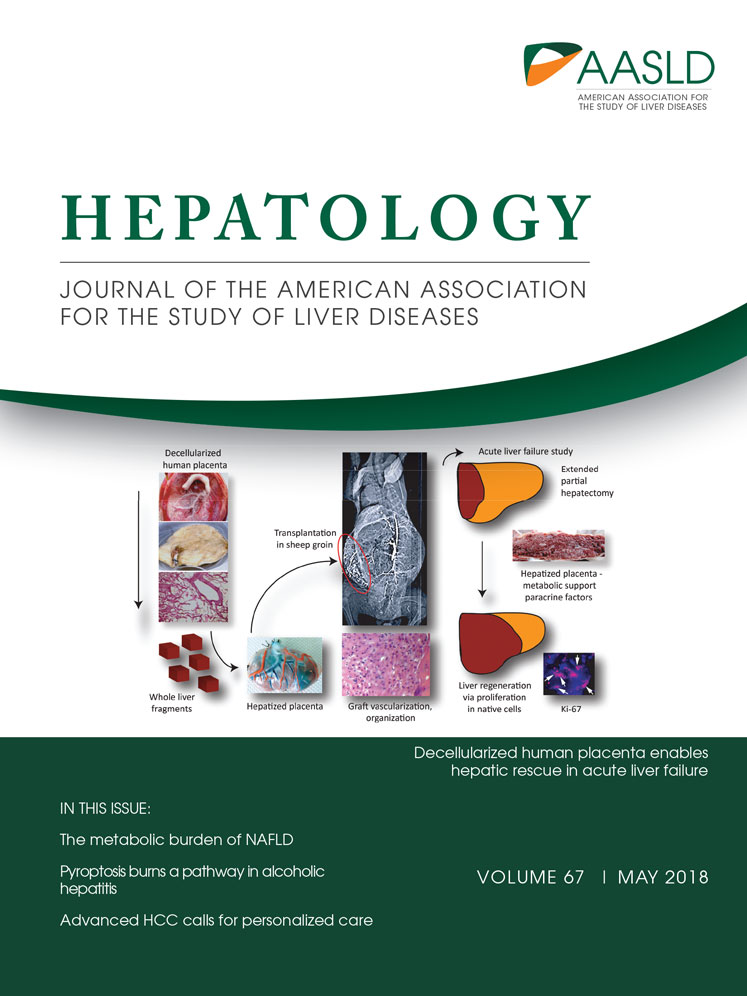

Anatomic studies, including corrosion casts (Supporting Fig. S1), revealed ample arterial and venous networks in placenta and cotyledons. This was important for tissue perfusion and mass transfer within cotyledons with implanted liver. After decellularization, vascular structures were intact without gross bulging or weakening (Fig. 1A). The DNA content after decellularization was <1% of intact placenta (4.6 μg DNA/mg dry weight). Nucleated cells were removed and stroma was well-preserved (Fig. 1B, 1C). Electron microscopy verified empty vascular and luminal spaces with ECM protrusions (Fig. 1D). Moreover, angiography revealed major and branching placental vessels leading into cotyledons were intact and filled promptly (Fig. 1E). This entry and exit of contrast from cotyledons occurred within seconds (Supporting Video 1). These parameters were naturally significant for tissue engineering. We also examined decellularized placenta after storage in saline at 4°C for days or lyophilization and cryopreservation at −80°C for months and found these were intact.

To ensure suitability of decellularized vessels, we tested tensile strength to bursting (Supporting Fig. S2). In matched arterial segments with or without decellularization (n = 10 each), including storage at −80°C, the mean burst point was 250 kPa versus 210 kPa, respectively (P > 0.05). These decellularized vessels bridged arterial defects in rats (n = 15) (Supporting Fig. S3), where all grafts showed excellent color and blood flow after 0, 3, 5, or 20 days (Supporting Fig. S4). Angiography confirmed graft patency. Similarly, decellularized veins bridged jugular vein defects (data not shown). Histology confirmed graft lumens were patent over up to 40 days. Remarkably, grafted vessels contained endothelial cells expressing von Willebrand factor and stromal cells expressing α-smooth muscle actin and desmin migrating from native tissues.

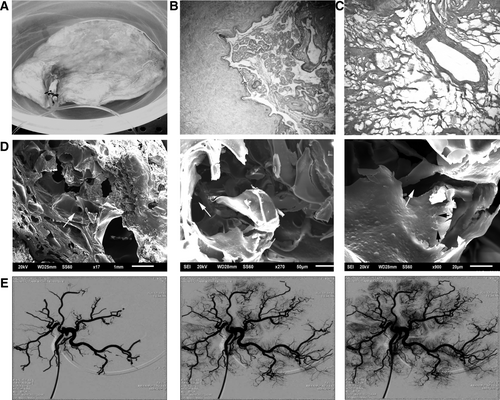

For transplantation of hepatized placenta, we trimmed excess tissue and injected donor liver through the capsule (Supporting Fig. S5). Histology verified liver fragments contained multiple cell types and tissues were intact despite passage through needles. Vessel casts and angiography confirmed transplanted tissue was well perfused (data not shown). After implantation in placenta and perfusion over 3 days in vitro, tissue maintained cord structure with sinusoids and was healthy (Supporting Fig. S5), To determine mass transfer, we perfused hepatized placenta with 99mTc-mebrofenin, which specifically enters and exits hepatocytes by way of defined transporters—members of solute carrier family and Abcc2, respectively.14 The tracer was incorporated uniformly over 5-10 minutes in hepatized placenta and cleared progressively over 60 minutes (Supporting Fig. S6). This 99mTc-mebrofenin uptake and excretion kinetics reproduced that in animals and people.10, 14 Moreover, it reemphasized hepatic tissue perfusion. In placenta hepatized with 10%-20% sheep liver, albumin was secreted in perfusate to 2.0 ± 0.2 g/L, 3.4 ± 0.3 g/L, and 3.0 ± 0.8 g/L on days 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In 60-minute samples with ammonium chloride infusion, urea was produced to 3.1 ± 2.2 mg/L, 3.4 ± 1.9 mg/L, and 4.8 ± 1.4 mg/L urea on days 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This proof of hepatic transport and synthetic functions coupled with angiographic and radiotracer evidences of graft perfusion set the stage for studies of hepatized placenta in vivo.

HEPATIZED PLACENTA IN SHEEP

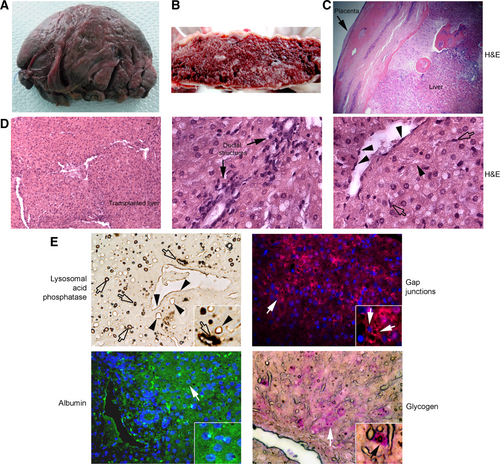

To avoid rejection, we used autologous sheep liver. Decellularized placentae were banked prospectively. To accommodate grafts in the inguinal region and to avoid the vascular “steal” phenomenon, excess placental tissue was trimmed before anastomosis with femoral vessels (Supporting Fig. S7). We examined hepatized placentae 1, 5-7, 14-15, 20, 30, and 45 days after transplantation (n = 1-2 each; total = 10) (Supporting Table S1). No sheep was lost during PH for liver harvest. In some instances, perfusion of hepatized placentae was verified by casts (Fig. 2A). Latex entered hepatized placentae and appeared in hepatic tissue. Typically, we transplanted hepatized placenta within 25-60 minutes after PH in sheep. Immediately after vascular anastomoses, grafts were well-perfused without excessive distension or rupture. Subsequently, the graft produced visible inguinal protuberance. Transplantation of hepatized placenta caused no morbidity or mortality. Evaluation of grafts after 1, 10, 15, and 45 days showed healthy placental and femoral vessel anastomoses. Histology at 1 day after grafting showed that placental cotyledons and vessels were filled with blood (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, tissue coalesced to form confluent hepatic sheets with hepatocytes and sinusoids containing blood and other cells within enclosures of connective tissue stroma from cotyledons and other cell types populated the placental capsule.

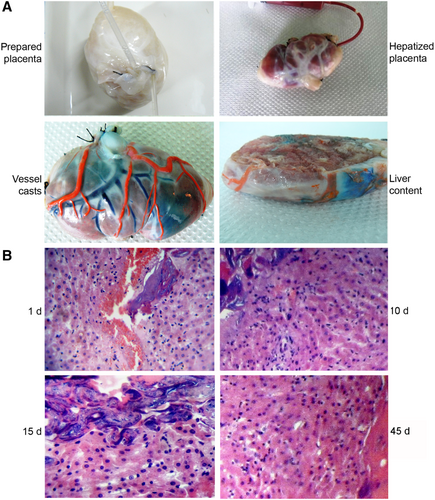

Ultrasound imaging and Doppler ultrasonography 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 days after transplantation verified blood flow in graft vessels (Supporting Fig. S8). Placental grafts were also evaluated by total body CT and angiography as indicated in images from 20 days after transplantation (Fig. 3). Blood flowed in both arterial and venous phases indicating grafts contained active arterial and venous channels.

More detailed analysis indicated additional vessels from subcutaneous tissue in graft capsule (Fig. 4A). The graft interior was typically filled with healthy tissue interspersed with blood-filled vascular spaces (Fig. 4B). Tissue sections showed graft contained confluent hepatic tissue (Fig. 4C). On occasion, less viable areas of transplanted tissue were also noted. Transplanted liver in grafts included hepatocytes with lobular organization in portal-like areas such as ductal structures and sinusoids containing blood and other cell types, leading to structures corresponding to central veins (Fig. 4D). We observed endothelial cells and additional cell types in hepatic vessels and sinusoids. To confirm the presence of LSECs and KCs, we stained lysosomal acid phosphatase activity, which is a hallmark of these cell types.13 Such LSECs and KCs with lysosomal acid phosphatase were abundant in transplanted tissue (Fig. 4E). To demonstrate whether transplanted hepatocytes maintained cell-to-cell communication for homeostasis, we localized gap junctions in adjacent cells. Immunostaining for connexin-32, which is specific to hepatocytes,15 indicated their presence in transplanted tissue (Fig. 4E). Moreover, hepatocytes in grafts expressed albumin (Fig. 4E). Also, hepatocytes contained glycogen, which was at higher levels in cells adjacent to vascular spaces compared with ductal areas to suggest position-specific hepatic function (Fig. 4E). 7 This unique hepatic organization is not readily found in hepatocytes transplanted into ectopic sites.8 Neither bile plugs nor other evidence for cholestasis were observed, suggesting that bile produced in transplanted tissue was secreted by bile canaliculi into adjacent sinusoidal blood followed by drainage into systemic circulation. This does not imply that bile ducts had been formed. Taken together, we concluded hepatized placenta engrafted and functioned in sheep over the long-term.

THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL OF HEPATIZED PLACENTA AND RESCUE OF SHEEP IN ALF

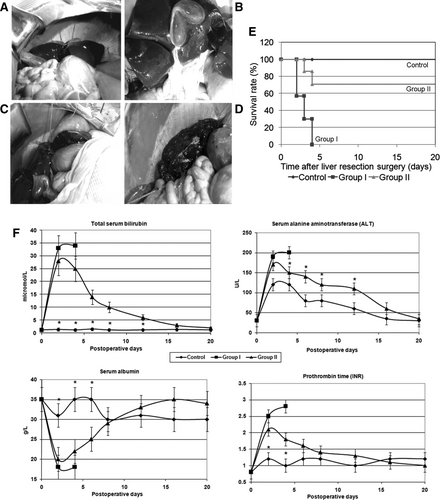

To determine whether hepatized placenta would replace deficient functions, we induced ALF in sheep by 85% PH, leaving behind only the caudate lobe plus portions of anterior lobes (Fig. 5A-5D). The hepatic loss caused progressive physical decline, lethargy, and death after 2-5 days. At necropsy, livers were small, indicating lack of liver regeneration. Then we hepatized banked placentae with liver from sheep subjected to 85% PH followed by transplantation into the same sheep within 1-2 hours. Placental grafts contained ∼20% by volume of liver. Animal groups were as follows: sham controls undergoing laparotomy without PH (n = 3), test group 1 with 85% PH to induce ALF (n = 7), and test group 2 with 85% PH plus hepatized placenta (n = 7). The placentae were grafted in the inguinal region as described above. All sham-treated controls recovered from surgery uneventfully (Fig. 5E). Group 1 with ALF worsened with lethargy and death in 7 of 7 (100%) animals. However, in group 2 with ALF plus hepatized placenta, 2 of 7 animals were less active and died on days 2 and 4 after PH, but 5 (71%) animals survived, which was superior to the outcome in group 1 (P < 0.05). Mortality in two group 2 animals was due to thrombosis of femoral vessel anastomoses and graft necrosis. Blood tests indicated higher serum ALT levels, peaking 2-3 days after surgery to 4-, 7-, and 6-fold above normal in controls, group 1 and group 2, respectively (Fig. 5F). Total serum bilirubin was unchanged in controls but increased in groups 1 and 2, peaking to 23- and 19-fold above normal 2-3 days after surgery, respectively. Serum albumin decreased in group 1 and group 2 to 18-20 g/L versus 30-35 g/L in controls 2-3 days after surgery. Similarly, group 1 and group 2 animals showed coagulation abnormalities peaking on days 2-3 after surgery. In surviving animals, liver tests normalized over time.

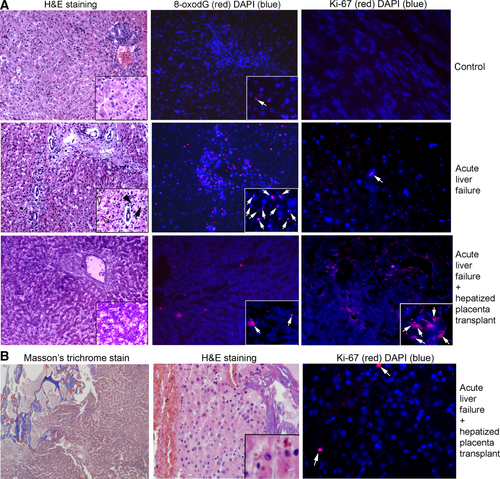

We euthanized surviving animals 20 days after PH. For histological evidences of liver injury, we examined nonsurvivors (groups 1 and 2), survivors with hepatized placenta (group 2), and sham-treated controls euthanized after 20 days. Liver morphology was normal in sham-treated controls (Fig. 6A). In groups 1 and 2 with ALF, interspersed hepatic necrosis or apoptosis and ductular reactions with mild biliary hyperplasia were noted, consistent with liver injury. In group 2 survivors, livers were healthy, although with greater KC abundances. We found widespread oxidative adducts on guanosine residues (8-oxo-dG) in group 1 with ALF (Fig. 6A, Supporting Fig. S9). This is a component of PH-induced DNA damage and ALF.16 By contrast, 8-oxo-dG adducts were infrequent in controls or group 2 following recovery over 20 days. Moreover, tissue analysis for regenerative activity showed extremely rare Ki-67–positive cells, 1 per 10-20 microscopic fields (×200) in healthy controls or group 1 with ALF. By contrast, we found 1-10 Ki-67–positive hepatocytes per field in group 2 sheep. Also, ductal cells with Ki-67 were present. Additional controls for Ki-67 staining were included (Supporting Fig. S9). Examination of placental grafts from group 2 verified that transplanted tissue was intact (Fig. 6B). These liver grafts were nonfibrotic with Masson's trichrome and were without inflammation, necrosis, or apoptosis in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Transplanted hepatocytes were healthy and hepatic sinusoids contained blood to indicate perfusion. In grafts, Ki-67 was expressed rarely (1-2 cells per 10-20 fields). This finding suggests that the native liver but not tissue in placental graft was regenerating in ALF.

Based on liver dimensions, we estimated a healthy sheep liver to be 877 ± 216 g (n = 3). The livers of group 1 sheep at death were 114 ± 55 g (n = 7), representing 13% ± 6% of healthy controls (P < 0.05). By contrast, after 20 days, the livers of group 2 sheep had recovered to 370 ± 78 g (n = 5), which was 3.2-fold greater than those in group 1, but was still only 42% ± 8% of healthy controls (P < 0.05). The placental grafts in group 2 sheep weighed 163 ± 12 g and 193 ± 8 g at transplantation and after sacrifice, respectively, which was 18%-19% of healthy liver mass and increased minimally compared with native livers in group 2.

Discussion

These studies established that human placenta offers suitable anatomical structure, vascular access, and ECM components for tissue engineering. Mechanically strong vessels and capillary networks in placenta ensured excellent tissue perfusion. Blood entered placental cotyledons rapidly via arterioles and exited equally rapidly from venules, which was verified by angiography. Latex casting indicated that after hepatization, vascular flow into cotyledons was maintained. Histology also verified the presence of blood within cotyledons and sinusoids of hepatic tissue in placenta. Radiotracer studies with 99m Tc-mebrofenin verified entry and exit of the tracer from cotyledons containing hepatic tissue. Radiological studies, including Doppler ultrasonography and CT verified blood flow in sheep. Moreover, ECM in vessels allowed migration of native endothelial and stromal cells during graft engraftment, which was critical for graft perfusion. These properties in hepatized placenta were highly significant for treating ALF. Because applications of decellularized organs have been restricted by major challenges, including thrombosis of damaged vessels with platelet aggregation, leading to only short-term tissue survival over hours or days,17 these large animal studies will be quite important.

The universal availability of human placenta would allow use of this otherwise discarded material for translational and clinical applications. Successful determination of metabolic and synthetic functions in placenta grafts will be useful as tools for drug testing or toxicological studies in vitro. This should benefit from the availability of multiple liver cell types from the outset. Moreover, individual cotyledons could be dissected for obtaining multiple units for such applications. These possibilities will be best realized by further studies with human tissues.

As indicated by our experience, decellularized placentae may be banked, including after lyophilization, and prepared with tissue grafts rapidly for use at short notice. The decellularization procedure itself is simple, requiring only common chemicals and resources. The high mechanical strength of decellularized placental vessels and their capacity to bridge arterial and venous defects indicates additional potential for vascular reconstruction or bypasses (e.g., in coronary or peripheral arterial diseases), which may be of further interest for tissue engineering.18 The migration of endothelial and other cell types in decellularized placental vessels suggested that necessary factors were immobilized in ECM. Similarly, the capsule of decellularized placenta, as well as its interior containing transplanted liver tissue, was revascularized by migrating cells. Previously, placental ECM was found to contain collagen, elastin and glycosaminoglycans, along with numerous cytokines, chemokines and growth factors, including contributors to chemotaxis (e.g., GCP, SDF-1), and angiogenesis or vasculogenesis (i.e., VEGF, HGF, EGF, FGFs, PDGF, TGF-beta).19 Interestingly, some of these substances also exert hepatotrophic effects, as in cases of VEGF, HGF, FGFs, EGF, IGF-1, IGFBPs, and so forth. Therefore, such properties in placental ECM likely benefited hepatic tissue engineering. Moreover, the placenta serves unique roles in other major biological processes, such as immunological mechanisms,9 which should have further benefits for tissue engineering.

We considered self-assembly of transplanted liver fragments in decellularized placenta to be important because this simultaneously provided multiple cell types in the graft. Introducing one cell type at a time into decellularized organs has been a general limitation for graft vascularization and survival.1 Here, reorganization of transplanted liver tissue was likely fostered by various cell types, including biliary cells, LSECs, and KCs. The multidimensional structure of liver fragments should have conferred advantages for tissue homeostasis through superior cell-to-cell interactions and access to autocrine or paracrine signals.6 Another aspect of tissue homeostasis involves metabolic intermediates that contribute in gene expression regulation.7 Similarly, gene expression is regulated by local cytokine levels; for example, networks of inflammation-associated cytokines, chemokines, and receptors under control of tumor necrosis factor α had major effects on survival of transplanted hepatocytes.20 The transplanted liver tissue was morphologically intact in placenta with hepatocytes expressing metabolic functions ex vivo or in vivo (i.e., glycogen storage, albumin secretion, urea synthesis, and hepatobiliary transport). Although we observed interspersed bile duct structures in hepatized placenta, bile was excreted in blood for disposal by the native liver as determined in other ectopic sites with 99mTc-mebrofenin,10 as also found here. These aspects will be helpful for drug testing or toxicology models where multiple liver cell types will be particularly valuable.

Our studies in sheep yielded a large animal model of ALF, where autologous tissue was convenient for demonstrating rescue with hepatized placenta by avoiding complexities due to rejection in allogeneic transplants. The capacity of transplanted tissue for ammonia-fixation, as shown by urea synthesis in our studies, would have contributed in treating metabolic encephalopathy, whereas provision of hepatic support should have allowed liver regeneration in sheep with ALF. The substantial hepatic DNA damage in sheep with ALF and regression of this damage during recovery in recipients of hepatized placenta were in agreement with such benefits for liver regeneration. Moreover, native liver regenerated after placental grafts, as indicated by Ki-67–positive cells, which were rare in grafted liver tissue. The native liver was also larger in animals receiving placental grafts and approached nearly 40%-50% of the size of healthy control liver. On the other hand, placental grafts enlarged only slightly during this period. Taken together, we concluded that native liver regeneration was advanced by grafted liver possibly by hepatic support and also paracrine signals from transplanted tissue. Although the nature of putative paracrine factors supporting liver regeneration is unknown, it should be noteworthy that transplantation of mature hepatocytes or of pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes in the peritoneal cavity also promoted liver regeneration in animals with ALF through metabolic support plus paracrine factor release, including with similar regression of hepatic DNA damage.8, 21

The successful application of hepatized placenta in ALF will be appropriate because this may allow bridging to orthotopic liver transplantation or time for regeneration of the native liver to avoid orthotopic liver transplantation altogether. The incorporation of multiple liver cell types in hepatized placenta should be of interest for studies of pathophysiological mechanisms or development of therapies in other conditions. For instance, LSECs constitute the major source of FVIII, which is deficient in hemophilia A, and transplantation of healthy LSECs was sufficient for curing hemophilia.22 Moreover, KCs also contributed in FVIII expression.23 It should be noteworthy that sheep modeling hemophilia A have been available for testing the therapeutic benefits of alternative approaches.24 Also, transplantation of healthy tissue in placental grafts could be useful for enzymatic deficiency states (e.g., Crigler-Najjar syndrome).2 Although these and other enzyme deficiency states are amenable to in vivo gene therapy, inadvertent systemic effects of gene transfer vectors could potentially be avoided by this approach. The procedure could be reversed and transplanted tissue removed for further safety, of course. Similarly, transplantation of pancreatic islets into the portal vein is of value for type-1 diabetes mellitus, but superior locations for transplanting islets where these could be revascularized are needed.25 Whether pancreatic islets could be combined with hepatization of placenta could be another possibility. The potential of cells derived from pluripotent or other stem cells for repopulating decellularized placenta26 should also be of interest.