Acute acalculous cholecystitis during zika virus infection in an immunocompromised patient

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by NIH sponsored Center for AIDS Research grant P30 AI050409 (to R.F.S.) and R21 AI129607 (to R.F.S.); Alves de Queiroz Family Fund for Research sponsored the Department of Gastroenterology. R.F.S. and N.F. report grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for Zika virus research, outside the submitted work.

Abbreviations

-

- AAC

-

- acute acalculous cholecystitis

-

- CNS

-

- central nervous system

-

- TA

-

- thymine-adenine

-

- ZIKV

-

- Zika virus

The focus of the Zika virus (ZIKV) outbreak has been on the predilection for infection of the central nervous system (CNS).1 Broader impact of ZIKV, including non-CNS involvement, is not well understood. We report a patient with acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC), which occurred during ZIKV acute infection.

Case Presentation

A 54-year-old male sought medical care with complaint of mild right hypochondrium abdominal pain lasting for 7 days with concomitant 3-day intermittent fever and 1-day nonpruritic maculopapular rash on torso and arms. One week before the onset of symptoms, the individual presented with aqueous diarrhea. Previous medical history included diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and large granular lymphocytic leukemia, for which he was treated with methotrexate, neutropenia, and past episodes of intermittent unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia attributed to Gilbert's syndrome (homozygous for the thymine-adenine [TA]7TAA-allele).

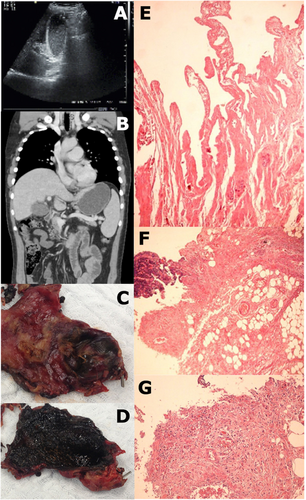

The patient was found to be dehydrated and febrile (38.3°C). He appeared to have mild abdominal discomfort, with a positive rebound tenderness sign but a negative Murphy's sign. Laboratory workup is shown in Table 1. Ultrasound and computed tomography findings were compatible with AAC (Fig. 1A,B). A comprehensive screening for infectious disease was conducted with negative results, but serum positive by polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for ZIKV. Similarly, tests confirmed ZIKV in bile and gallbladder tissue by RT-PCR, with a 100% homology to a ZIKV sequence (see Supplementary Materials).

| Laboratory Results | Normal Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 12.6 g/dL | 13.0-18.0 g/dL |

| WBC | 5,060/mm3 | 4,000-11,000/mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 1,380/mm3 | 1,600-7,000/mm3 |

| Platelets | 129,000/mm3 | 140,000-450,000/mm3 |

| Creatinine | 1.16 mg/dL | 0.7-1.2 mg/dL |

| ALT | 16 U/L | <41 U/L |

| AST | 17 U/L | <37/UL |

| GGT | 43 U/L | 8-61 U/L |

| ALP | 59 U/L | 40-129 U/L |

| Indirect bilirubin | 1.08 mg/dL | 0.1-0.6 mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.61 mg/dL | <0.3 mg/dL |

| C-reactive protein | 34 mg/L | <5.0 mg/L |

| Urinalysis | No abnormalities | No abnormalities |

- Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

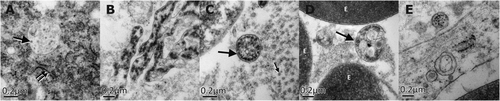

The patient received empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy, including ceftriaxone (2 g/day) and metronidazole (2.25 g/day). Nonetheless, the patient's general condition continued to deteriorate, and thus a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. No Murphy's sign developed during disease course. Surgical exploration (lasting 290 minutes) was difficult because of numerous adhesions and pericholecystic plastron. In addition, the patient was hyperthermic and hypotensive. Fluids and noradrenaline were administered and vital parameters stabilized. Intraoperative findings comprised an enlarged gallbladder with thickened walls and viscous bile inside with no calculi. Gallbladder histology revealed large portions of organizing inflammation and necrosis, and small vessels were obliterated by fibrin thrombi (Fig. 1E-G), and electron microscopy showed Flavivirus-like particles in both intracellular and extracellular compartments and emerging out of an endothelial cell into a vessel (Fig. 2).

The patient was discharged on day 4 with full recovery/improvement in vital parameters. During disease course, the patient did not develop any changes in mental status or neurological impairment, suggesting that dissemination of ZIKV disease had unlikely occurred. As of February 2017, he is alive and underlying pathologies are under control.

Discussion

AAC physiopathology is poorly defined and appears to be multifactorial. It can be caused by a variety of infectious disease agents or a resultant complication during disease course.2 Reports have linked AAC to other Flavivirus infections, such as dengue fever.3 In the current case, ZIKV detection in the gallbladder endothelium suggested ZIKV-induced microangiopathy. Several AAC cases have been associated with gallbladder microangiopathy, potentially leading to decreased emptying of the stimuli, cell death, and, ultimately, secondary bacterial growth.4

Recent reports suggest the potential for more severe infections and complications in immunocompromised hosts during ZIKV infection.5, 6 Mechanistic insights and the full clinical spectrum of ZIKV infection is unclear and further studies are required.

In this case, AAC may have resulted from multiple factors, including viral infection and host factors. We hypothesize that ZIKV-related microangiopathy induced by endothelium infection may have led to cell death and gallbladder necrosis. Finally, the patient's immunocompromised status might have impaired his ability to fight against both viral and bacterial infections. This report provides a cautionary warning for clinicians to consider the potential increased risk and disease severity and/or atypical presentations with ZIKV infections in immunocompromised patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient in this case for his willingness to provide detailed medical and biological samples; Hui-Mien Hsiao for technical assistance; Cristina Takami Kanamura for the immunohistochemistry reactions; James Kohler for writing assistance; and Marcia Lea Wajchenberg for illustration assistance.