Acute hepatic porphyrias: Recommendations for evaluation and long-term management

Supported in part by the Porphyrias Consortium (U54 DK083909), which is a part of the NCATS Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), funded through a collaboration between NCATS and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (K23 DK095946, to M.B.); and the American Porphyria Foundation 's Protect the Future Program (to B.W.).

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Anderson consults for Alnylam and Recordati Rare Diseases. Dr. Bonkovsky consults and received grants from Alnylam. He consults for Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Moderna, Recordati, and Stoke. Dr. Bissell consults for Recordati, Alnylam, and Mitsubishi-Tanabe. Dr. Desnick consults and received grants from Recordati. He consults and holds intellectual property rights with Alnylam. Dr. Bloomer consults for Recordati and Mitsubishi-Tanabe. He received grants from Alnylam. Dr. Balwani consults and received grants from Alnylam. She consults for Recordati and Mitsubishi-Tanabe. Dr. Phillips consults for Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Recordati, Alnylam, and Argus.

Abstract

The acute hepatic porphyrias are a group of four inherited disorders, each resulting from a deficiency in the activity of a specific enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway. These disorders present clinically with acute neurovisceral symptoms which may be sporadic or recurrent and, when severe, can be life-threatening. The diagnosis is often missed or delayed as the clinical features resemble other more common medical conditions. There are four major subgroups: symptomatic patients with sporadic attacks (<4 attacks/year) or recurrent acute attacks (≥4 attacks/year), asymptomatic high porphyrin precursor excretors, and asymptomatic latent patients without symptoms or porphyrin precursor elevations. Given their clinical heterogeneity and potential for significant morbidity with suboptimal management, comprehensive clinical guidelines for initial evaluation, follow-up, and long-term management are needed, particularly because no guidelines exist for monitoring disease progression or response to treatment. The Porphyrias Consortium of the National Institutes of Health's Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, which consists of expert centers in the clinical management of these disorders, has formulated these recommendations. These recommendations are based on the literature, ongoing natural history studies, and extensive clinical experience. Initial assessments should include diagnostic confirmation by biochemical testing, subsequent genetic testing to determine the specific acute hepatic porphyria, and a complete medical history and physical examination. Newly diagnosed patients should be counseled about avoiding known precipitating factors. The frequency of follow-up depends on the clinical subgroup, with close monitoring of patients with recurrent attacks who may require treatment modifications as well as those with clinical complications. Comprehensive care should include subspecialist referrals when needed. Annual assessments include biochemical testing and monitoring for long-term complications. These guidelines provide a framework for monitoring patients with acute hepatic porphyrias to ensure optimal outcomes. (Hepatology 2017;66:1314-1322)

Abbreviations

-

- AHP

-

- acute hepatic porphyria

-

- AIP

-

- acute intermittent porphyria

-

- ALA

-

- 5′-aminolevulinic acid

-

- ALAS1

-

- 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase

-

- ASHE

-

- asymptomatic high excretors

-

- GnRH

-

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HCP

-

- hereditary coproporphyria

-

- PBG

-

- porphobilinogen

-

- VP

-

- variegate porphyria

The acute hepatic porphyrias (AHPs) are inborn errors of heme biosynthesis. AHPs include three dominantly inherited disorders, acute intermittent porphyria (AIP), hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and variegate porphyria (VP), as well as the rare autosomal recessive 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria.1, 2 These disorders are all characterized by acute neurovisceral symptoms that are clinically indistinguishable. In addition, patients with HCP and VP may have chronic blistering skin lesions on sun-exposed areas.1-3 The combined prevalence of these disorders is estimated to be ∼5 per 100,000, with instances of higher prevalence due to founder effects.4-6 The penetrance of AIP, HCP, and VP is low, as >90% of heterozygotes for disease-causing mutations remain asymptomatic for life.4, 7

These disorders are clinically heterogeneous and may present with various symptoms, primarily due to effects on the nervous system. There can be multisystem involvement affecting the skin, liver, and kidneys.1 Because the symptoms are nonspecific, the AHPs are often misdiagnosed as other more common conditions and, therefore, not adequately treated.8 Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acute attacks are available2, 8; however, there are no long-term management guidelines.

Here, we outline optimal follow-up and management guidelines for AIP, HCP, and VP patients classified into four subgroups: 1 latent genetic mutation carriers who are asymptomatic and biochemically inactive (normal levels of the porphyrin precursors 5′-aminolevulinic acid [ALA] and porphobilinogen [PBG]), 2 asymptomatic high excretors (ASHE) who do not currently have acute attacks but are biochemically active (increased urinary ALA and PBG ≥4 times the upper limit of normal), 3 sporadic attack patients with infrequent acute attacks (<4 per year), and 4 recurrent attack patients (≥4 per year). The majority of symptomatic AHP patients are those with sporadic attacks; approximately 3%-5% have recurrent attacks.4 The incidence of asymptomatic latent patients is unknown, though studies indicate they are more frequent than previously thought.7, 9 ASHE represents about 10% of AHP patients.10, 11 These guidelines are based on the consensus recommendations from the physician-investigators from the National Institutes of Health–funded Porphyrias Consortium.12

Pathophysiology

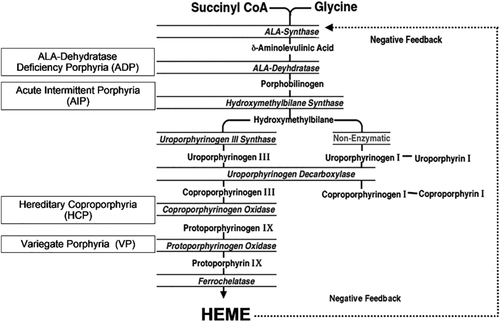

In all four AHPs, the respective enzyme deficiency predisposes patients to certain triggering factors that lead to abnormally high accumulations of the neurotoxic porphyrin precursors ALA and PBG, which can precipitate an acute neurovisceral attack. These include certain drugs, stress, fasting, alcohol use, smoking, and hormones.8, 13 These precipitating factors markedly increase the demand for hepatic heme, and the decreased hepatic free heme induces the synthesis of 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS1), the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the heme-biosynthetic pathway, by a negative feedback mechanism (Fig. 1). Due to the approximately half-normal enzyme activity in the autosomal dominant AHPs, the marked induction of ALAS1 results in the increased production and subsequent accumulation of ALA and PBG, which are always markedly elevated during acute attacks.1, 14 Urine PBG is typically elevated higher than ALA in AIP, VP, and HCP.8 Due to the severe enzyme deficiency of aminolevulinic acid dehydratase in 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria, the ALA is markedly increased with a normal to slightly increased urinary PBG and porphyrins.1, 15 As 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria is very rare, it is not discussed in this review.

Heme-biosynthetic pathway showing enzymatic defect in AHPs.

Initial Assessment

Initial assessment of a patient with a known diagnosis of an AHP includes a baseline detailed history, physical examination, and neurologic assessment for peripheral motor and sensory deficits as well as cranial nerve abnormalities, thereby establishing a baseline for future assessments (Table 1). In HCP and VP, chronic cutaneous blistering, milia, pigmented areas, and scars may occur on sun-exposed skin, especially dorsal hands and face.16, 17 Otherwise, the examination between attacks is likely to be unremarkable.

| Complete medical and family history |

|---|

| Detailed physical exam (including vital signs, neuro exam, skin exam) |

| Review of precipitating factors |

| Review of medications |

| Counseling (nutrition, avoidance of precipitating factors, inheritance, etc.) |

| Quality of life assessment |

| Porphyria-specific biochemical tests: |

| Urine PBG/g creatinine |

| Urine ALA/g creatinine |

| Urine porphyrins/g creatinine |

| Fecal porphyrins (suspected HCP and VP only) |

| Plasma porphyrins (suspected HCP and VP only) |

| PBG deaminase (optional for suspected AIP) |

| Standard blood tests: |

| CBC |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel with eGFR |

| Ferritin and iron studies (if anemic) |

| AFP (if > 50 years) |

| Genetic testing (one of the following options): |

| Mutation analysis for HMBS (AIP), PPOX (VP), or CPOX (HCP) if a specific acute porphyria is suspected |

| Acute porphyria panel |

| Targeted mutation analysis for relatives of the index case (if family mutation is known) |

| Hepatic monitoring (symptomatic and ASHE only): |

| Liver ultrasound if > 50 years |

| If history or symptoms of neuropathy (symptomatic only): |

| NCV/EMG |

- Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CBC, complete blood count; CPOX, coproporphyrinogen oxidase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EMG, electromyogram; HMBS, hydroxymethylbilane synthase; NCV, nerve conduction velocity; PPOX, protoporphyrinogen oxidase.

BIOCHEMICAL TESTING

In patients with a prior diagnosis, it is essential to obtain previous records that confirm the diagnosis; otherwise, repeat diagnostic testing including quantitative estimation of the urine PBG, ALA, and porphyrins in a spot urine sample, with results normalized to urine creatinine, is required. A 24-hour collection is unnecessary.8 For HCP and VP, urine PBG and ALA levels may be less elevated during attacks than in AIP and are more likely normal between acute episodes. Normal urine PBG in symptomatic patients excludes the three most common AHPs as the cause.8 An exception is a very dilute urine sample that may lead to “false-negative” spot urine if not normalized to urine creatinine. Short delays in refrigerating, freezing, or shielding the samples from light exposure are unlikely to cause false-negative results. Urine/plasma porphyrin analyses may differentiate the specific AHP, but mutation identification is definitive.8

GENETIC TESTING

Once a diagnosis of AHP is biochemically confirmed, gene sequencing is required to identify the mutation in an index case and to determine the specific AHP. If biochemical tests suggest a specific AHP, the respective causative gene should be sequenced. If biochemical results are incomplete or not definitive for a specific AHP, genetic testing should include sequencing the three genes for mutations causing AIP, VP, or HCP (AHP panel). Identification of the specific mutation in an index case enables testing of at-risk family members. Genetic testing is not performed as first-line testing because, generally, there are no common mutations for these disorders, with the exception of founder mutations for AIP in Scandinavia and VP in South Africa.5, 6 In addition, there are no strong genotype–phenotype correlations that predict disease severity or prognosis, although certain mutations may be associated with recurrent AIP attacks.18, 19 Genetic testing should be performed in a laboratory experienced with distinguishing pathogenic mutations from incidental polymorphisms.7

BASELINE ASSESSMENT

Laboratory Tests

A complete blood count and ferritin levels should be obtained at baseline and at least yearly. Iron deficiency is not caused by AHPs, but it is common in young women, can cause chronic symptoms, and should be treated. Hyponatremia occurs in 25%-60% of symptomatic cases, typically during attacks, and should resolve after recovery.20

Renal Evaluation

A metabolic panel should include a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate. The AHPs pose a risk of developing renal disease, typically chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy or focal cortical atrophy.21, 22 Recent studies suggest that a gene variant in the human peptide transporter 2 is associated with porphyria-related nephropathy.23

Latent cases are apparently not at risk for chronic kidney disease.24 Risk of renal disease in ASHE is unknown. Tachycardia and systemic arterial hypertension due to increased catecholamine production usually resolve after resolution of an acute attack. However, some patients may develop chronic hypertension requiring aggressive monitoring and treatment, which may help prevent renal damage. Whether chronic hypertension is a complication of AHP or a concurrent condition is uncertain.22, 25 Referral to a nephrologist is recommended if hypertension is not controlled by first-line treatment or when renal dysfunction is first recognized.

Hepatic Evaluation

Liver function tests should be obtained for all patients at baseline. Serum aminotransferases are elevated in ∼13% of patients during an acute attack and in some clinically asymptomatic patients.13, 26 Patients with persistently abnormal serum aminotransferases should be evaluated for other causes of liver disease. A liver biopsy may help diagnose concurrent conditions, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Neurologic Evaluation

The major symptoms and signs of AHPs are due to effects on the nervous system. Acute attacks can be complicated by an axonal motor neuropathy and paresis.27 A neurological consultation is often useful between attacks for better assessment of positive neurological finding(s) or unexplained symptoms and for differentiating other neurological conditions with similar signs and symptoms. Patients with frequently recurring attacks may develop chronic neuropathic pain. This complication has been poorly studied, and its prevalence and causes are unknown. Nerve conduction and electromyographic studies may detect a chronic neuropathy as the cause of ongoing pain, sensory loss, or muscle weakness.28, 29 Prospective studies are needed in patients with sporadic and recurrent attacks and ASHE.

Management

IDENTIFYING, COUNSELING, AND MONITORING FOR EXACERBATING FACTORS

An important part of the management of AHP patients is to identify and avoid or eliminate factors that precipitate or worsen acute attacks. Patients should be counseled to avoid possible precipitating factors and to consult publicly available drug databases before starting new medications8, 30 (http://www. porphyriafoundation.com/drug-database, http://www.drugs-porphyria.org/).

Latent carriers are likely to be less susceptible to attacks but should also be counseled about precipitating factors. Patients should maintain a balanced diet and avoid prolonged fasting or crash dieting. Carbohydrate loading is thought to be beneficial by some patients in the early stages of an acute attack, but evidence supporting clinical benefit is lacking. Moreover, sustained adherence to a high-carbohydrate diet does not prevent attacks and is not recommended. Patients planning to lose weight should do so gradually with advice from a dietitian. Crash diets and bariatric surgery have triggered attacks.31

Patients with severe recurrent symptoms should avoid alcohol and smoking, which can precipitate attacks. ASHE and latent patients may be able to consume alcohol in moderation without inducing symptoms. Patients with HCP and VP who have cutaneous lesions should avoid sunlight exposure and wear protective clothing to avoid developing skin lesions.16, 17 Medical alert bracelets are recommended for all AHP patients.8

In addition, all heterozygotes, whether symptomatic, ASHE, or latent, should receive appropriate genetic counseling about inheritance. In general, pregnancy is not avoided because it is usually well tolerated. Moreover, treatment is available and prognosis favorable for any offspring who inherit the familial mutation, even if they become symptomatic.

MANAGEMENT DURING ANESTHESIA AND SURGERY

Patients who will undergo surgical procedures should inform physicians about their diagnosis, and adequate time should be provided for evaluation and planning. Preprocedure evaluation by the anesthesiologist and surgeon should include review of current medications and planning anesthesia using agents that are safe in AHPs. For patients having frequently recurring attacks, a prophylactic hemin infusion to prevent a perioperative attack can be considered prior to surgery and postoperatively, but specific guidelines are lacking. Intravenous fluids containing dextrose should be given routinely to AHP patients who are fasting for surgery including latent cases. Similar considerations apply during severe medical illnesses that cause metabolic stress and compromise nutritional intake.

PREVENTION OF RECURRENT ATTACKS

Hemin

Hemin has been used prophylactically to prevent recurrent attacks that continue even after identifiable precipitating factors are eliminated.32 Patients with four or more attacks per year are candidates for either prophylactic infusions or “on-demand” infusions at an outpatient center. Management of these patients is highly individualized. A single prophylactic infusion can be given monthly, bimonthly, or weekly to prevent recurrent attacks. As heme is metabolized rapidly by heme oxygenase, its effects on ALAS1 are not likely to last for more than 1 week, so less frequent dosing may not be effective, although some patients have reported benefits with monthly or biweekly infusions. The need for ongoing prophylactic hemin treatment should be reassessed after 6-12 months of repeated prophylactic therapy. To assess whether continued prophylaxis is needed, interrupting therapy and restarting if necessary may be more effective than tapering the dose or frequency of administration.

In patients who experience prodromal attack symptoms, hemin can be administered “on demand” at an outpatient center to control symptoms and prevent hospitalization. Patients may receive a single outpatient infusion or consecutive-day doses based on their clinical status. However, patients who have already progressed to severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and hypertension are not candidates for outpatient therapy. These patients can deteriorate rapidly and should be managed in the inpatient hospital setting.

As hemin contains 9% iron by weight, long-term repeated hemin administration can lead to iron overload and contribute to hepatic damage and fibrosis.33 Therefore, serum ferritin should be measured in patients receiving prophylactic or frequent hemin treatment, at 3-month to 6-month intervals or after every ∼12 doses. To avoid acute-phase effects, serum ferritin is measured between attacks and before the next dose of hemin. Iron reduction by therapeutic phlebotomy should begin when ferritin levels are >1,000 ng/mL or earlier, and serum ferritin should be reduced to a goal of ∼150 ng/mL. Many such patients have indwelling venous ports due to limited venous access, and frequent small-volume phlebotomies may be more feasible.

Carbohydrate Loading

Carbohydrate loading with glucose tablets or concentrated dextrose solutions has been used by some patients in the early stages of an acute attack, but there are no clear clinical data showing a benefit. There is no evidence to suggest that outpatient prophylactic dextrose infusions offer any benefit.

Cyclic Attacks

Some women with AHP develop cyclic attacks related to the menstrual cycle, typically during the luteal phase when progesterone levels are highest and resolving with onset of menses. These attacks can be prevented by (1) recognizing and removing another exacerbating factor that is additive, (2) a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue, (3) switching to a low-dose hormonal contraceptive, or (4) prophylactic hemin infusions. Oophorectomy and hysterectomy should not be considered unless there is another indication. Measuring serum progesterone at the onset of symptoms is useful for identifying luteal-phase and potentially progesterone-induced attacks.

GnRH treatment is initiated during the first 1-3 days of a cycle to prevent an initial agonistic effect that induces ovulation.34 Although these agents are agonists, with prolonged use gonadotropin receptors are down-regulated and ovulation and corpus luteum formation are prevented.35, 36 Menopausal symptoms and bone loss can be prevented with a low-dose estradiol skin patch after ∼3 months, if the GnRH analogue is preventing attacks. Treatment beyond 6 months is not recommended without low-dose estrogen supplementation.35 Switching to a trial of an oral low-dose estrogen–progestin combination after 6 months will determine if the low-dose progestin is well tolerated. If a low-dose oral contraceptive combination is started initially and attacks continue, it is difficult to determine whether or not these might be due to the low-dose progestin. In women with frequent attacks that seem partially related to the cycle, a GnRH analogue can be tried for up to 3 months, then discontinued if not effective. Women treated successfully with a GnRH analogue to prevent cyclic attacks are at risk for osteoporosis, which can be prevented by supplemental estrogen or by switching to a low-dose oral contraceptive as described above. Bone density should be assessed yearly to assure that there is no continuing bone loss. There is a continuing risk of endometrial dysplasia in the absence of a progestin, and the endometrium should be monitored at least annually by a gynecologist. The need for ongoing use of a GnRH analogue should be evaluated by interrupting treatment at intervals of 6-12 months or as individually determined.

Single prophylactic hemin infusions, either weekly or once or twice during the luteal phase, can prevent cyclic attacks. This treatment requires visits to an infusion center, and timing to coincide with the luteal phase is often difficult.

LIVER AND KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION

Orthotopic liver transplantation has been successful and indeed curative in patients with severe, disabling, intractable attacks that are refractory to hemin therapy. Because orthotopic liver transplantation is associated with morbidity and mortality, it is considered a treatment of last resort. In addition, patients who already have advanced neuropathy with quadriplegia and respiratory paralysis are considered poor candidates for transplantation.37-40

AIP patients with advanced renal disease tolerate and benefit from renal transplantation, and exacerbations of porphyria do not occur with exposure to commonly used immunosuppressive agents. Rarely, AIP patients with end-stage renal disease develop elevations in plasma porphyrins and blistering skin lesions, resembling those seen in porphyria cutanea tarda, and respond well to renal transplantation.41 Some patients with both repeated attacks and end-stage renal disease have benefited from combined liver and kidney transplantation.42

NEWER THERAPIES

Preclinical studies in mice with AIP with an RNAi therapeutic that targets hepatic ALAS1 demonstrated that RNAi-mediated silencing of hepatic ALAS1 could prevent and treat acute attacks.43 Clinical trials with Givosiran, a subcutaneously administered GalNAc-conjugated RNAi therapeutic targeting hepatic ALAS1 to assess prevention of attacks are in progress.

Follow-Up Management

Continued monitoring must be individualized and is essential in an effort to prevent acute attacks, hospitalization, and long-term complications. Evaluation schedules based on age, clinical features, and ongoing treatment needs are presented in Table 2.

| ASHE | Sporadic and Recurrent Attacks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent | Every 12 Months | Every 3 Months | Every 6 Months | Every 12 Months | |

| Medical history | As clinically indicated | X | X | ||

| Physical examination | X | X | |||

| Medication review | X | X | |||

| Quality of life | X | X | |||

| Biochemical tests | |||||

| Urine ALA and PBG | X | X | |||

| Additional laboratory tests | |||||

| CBC | X | X | |||

| CMP with eGFR | X | X | |||

| Hepatic function panel | X | X | |||

| Monitoring for HCC (>50 years) | |||||

| Liver US | X | X | |||

| AFP | X | X | |||

| Treatment monitoring | |||||

| If receiving prophylactic hemin therapy | N/A | N/A | |||

| Ferritin with iron studies | X | ||||

| If receiving GnRH analogue | |||||

| DXA | X | ||||

| Gyn screening | X | ||||

- Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Gyn, gynecological; US, ultrasound.

Symptomatic AHP patients should be followed at least annually and more frequently if they are receiving prophylactic treatment or continue to have acute attacks. After hospitalization for an acute attack, a follow-up visit should occur within 1 month for reassessment of precipitating factors, preventive measures, and management of pain and other symptoms. ASHE should be followed annually, and latent patients should be followed if clinically indicated.

PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION AND PAIN MANAGEMENT

Recurrent attacks and chronic pain can have a significant impact on physical and emotional well-being. Patients with recurrent attacks have a significantly decreased quality of life due to acute attacks, chronic pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.44, 45 Psychiatric evaluation and treatment for coexistent anxiety or depression can provide long-term benefit. Patients with chronic pain may require daily pain medication and are at risk for opioid dependence. These patients should be referred to a pain-management specialist for optimal treatment.

SCREENING FOR HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

The risk for developing chronic hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis may be greater in AHP patients than the general population.46 An increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is well documented. HCC develops more commonly in symptomatic patients over age 60, although ASHE may be at increased risk as well.47, 48 There is no evidence of increased risk of HCC with latent porphyria. Liver imaging for HCC is recommended at 6-month to 12-month intervals after age 50 for patients with recurrent attacks or past symptoms. There are limited data available on screening ASHEs. Hepatic imaging should be the primary screening method; measurement of serum alpha-fetoprotein is also recommended, but it has not been found elevated in most AHP patients with HCC. Patients should be vaccinated against viral hepatitis.

FERTILITY, PREGNANCY, AND CONTRACEPTION

Fertility is not impaired in women with AHPs, unless a patient is debilitated and anovulatory due to repeated attacks. Fertility-inducing drugs have been reported to precipitate acute attacks and should be used with caution.49 Pregnancies are generally well tolerated by women with AHPs.50, 51 A minority of women have more frequent attacks during pregnancy, and sometimes the disease is first diagnosed during pregnancy. Increased rates of miscarriage have been reported in patients with a history of recurrent attacks.52 Therefore, a preconception evaluation is recommended to discuss risks during pregnancy, and patients should be followed by a high-risk obstetrician during pregnancy. The risk of attacks during pregnancy in latent and ASHE cases is presumably less than in those with previous attacks, but data are limited.

Although progesterone levels are high during pregnancy, undefined compensatory mechanisms may be protective. Nausea and decreased caloric intake that frequently occur during the first trimester may contribute to developing attacks. Attacks during pregnancy are safely treated with hemin, and interruption of pregnancy due to an acute attack is rarely needed.53 Monitoring should continue after delivery because acute attacks can occur during the postpartum period.

Oral contraceptives, hormone-releasing implants, and intrauterine devices can precipitate acute attacks.54 Evidence points to progestins rather than estrogens as the triggering agents. Contraceptive methods involving only progesterone or a progestin, including implants and intrauterine devices, should be avoided because these can achieve significant systemic levels and therefore liver exposure. Estrogen–progestin combinations can exacerbate AHPs, although newer low-dose combinations may be better tolerated than older higher-dose combinations.55 Women with frequent attacks may be more susceptible to their effects than ASHEs and latent cases; but experience is limited, so caution is important whenever they are used. Because reported experience is meager, there are no recommendations with regard to specific combinations. Barrier methods and intrauterine devices that do not contain progesterone are safe.

Conclusions

The AHPs are complex, clinically heterogenous disorders affecting multiple organ systems that require a multidisciplinary management approach to avoid significant morbidity and decreased quality of life. These recommendations for diagnosis, treatment, and counseling of patients should establish a standard of care for AHP patients and should be individualized for each patient, with the frequency of follow-up and testing tailored to the patient's clinical response.

REFERENCES

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.