Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with ribavirin for 24 weeks in hepatitis C virus patients previously treated with a direct-acting antiviral regimen

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Gane advises and is on the speakers' bureau for Gilead and AbbVie. He advises Janssen. Dr. Shiffman consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from AbbVie, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He consults, advises, and is on the speakers' bureau for Gilead and Intercept. He consults and is on the speakers' bureau for Daiichi Sankyo. He consults for Optum Rx. He is on the speakers' bureau for Bayer. He received grants from CymaBay, Galectin, Genfit, Intercept, Immuron, NGM, Novartis, and Shire. Dr. Stedman advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead. She advises and is on the speakers' bureau for AbbVie. She advises MSD. Dr. Davis consults, is on the speakers' bureau for, owns stock in, and received grants from Gilead. He consults, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from AbbVie. Dr. Hinestrosa is on the speakers' bureau for Gilead, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AbbVie. Dr. Thompson consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead. Dr. Sulkowski advises and received grants from Gilead, AbbVie, and Merck. He advises Janssen and Trek. Dr. Dvory-Sobol is employed and owns stock in Gilead. Dr. Huang is employed and owns stock in Gilead. Dr. Osinusi is employed by and owns stock in Gilead. Dr. McNally is employed and owns stock in Gilead. Dr. Brainard is employed by and owns stock in Gilead. Dr. McHutchison is employed by and owns stock in Gilead.

Supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Abstract

The optimal retreatment strategy for patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus who experience virologic failure after treatment with direct-acting antiviral–based therapies remains unclear. In this multicenter, open-label, phase 2 study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (400 mg/100 mg) plus weight-adjusted ribavirin administered for 24 weeks in patients who did not achieve sustained virologic response after prior treatment with direct-acting antiviral regimens that included the nucleotide analogue nonstructural protein 5B inhibitor sofosbuvir plus the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor velpatasvir with or without the nonstructural protein 3/4A protease inhibitor voxilaprevir. The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after the cessation of treatment. In total, 63 of 69 (91%; 95% confidence interval, 82%-97%) patients achieved sustained virologic response at 12 weeks, including 36 of 37 (97%; 95% confidence interval, 86%-100%) patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection, 13 of 14 (93%; 95% confidence interval, 66%-100%) patients with genotype 2 infection, and 14 of 18 (78%; 95% confidence interval, 52%-94%) patients with genotype 3 infection. Most adverse events were of mild or moderate severity. The most frequently reported adverse events were fatigue, nausea, headache, insomnia, and rash. One patient (1%) with genotype 1a infection discontinued all study drugs due to an adverse event (irritability). Conclusion: Retreatment of patients who previously failed direct-acting antiviral–based therapies with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin for 24 weeks was well tolerated and effective, particularly those with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 2 infection. (Hepatology 2017;66:1083-1089).

Abbreviations

-

- DAA

-

- direct-acting antiviral agent

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- LLOQ

-

- lower limit of quantification

-

- NS

-

- nonstructural (protein)

-

- RAS

-

- resistance-associated substitution

-

- SVR

-

- sustained virologic response

-

- SVR12

-

- SVR at 12 weeks

-

- ULN

-

- upper limit of normal

The therapeutic outlook for patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) has been transformed by the development of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) targeting viral proteins critical to viral replication.1-3 Approved combinations of these agents provide rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) well over 90% in most patients, including those who have historically been difficult to treat. However, the patients who do not achieve SVR with existing DAA regimens have no clear treatment options, and there have been few studies evaluating retreatment strategies for these patients.3, 4 A number of questions remain unanswered concerning retreatment, in particular, the effect of resistance. There is increasing evidence that baseline and treatment-emergent resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) can have an effect on response, but the implications for retreatment are still unclear.5

Sofosbuvir is a nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B) polymerase inhibitor that has been approved to treat patients of all genotypes in combination with other DAAs. Velpatasvir is an HCV NS5A inhibitor with pangenotypic potency. The combination of sofosbuvir 400 mg and velpatasvir 100 mg has been approved for the treatment of adult patients with chronic genotype 1-6 HCV infection with and without compensated cirrhosis.6 Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir therapy is associated with high antiviral efficacy, achieving SVR rates ≥95% in patients with HCV genotype 1-6 infection in phase 3 clinical trials.7-9

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with ribavirin administered for 24 weeks in patients who failed prior DAA-based therapies in clinical trials sponsored by Gilead.

Patients and Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENTS

We conducted this open-label phase 2 study from December 2014 to July 2016 at 31 sites in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (NCT02300103). We enrolled patients from four studies: three phase 2 clinical trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with or without ribavirin (NCT01858766, NCT01909804, and NCT01826981) and one phase 2 trial of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus voxilaprevir (NCT02202980).

Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age with documented HCV infection (screening HCV RNA ≥lower limit of quantification [LLOQ]) of any genotype who had previously received a DAA-containing regimen in a Gilead-sponsored clinical study and who had completed all treatment and posttreatment assessments as specified by the protocol of their prior study. Patients could have compensated cirrhosis (Metavir score = 4, Ishak score ≥5, or a FibroTest score >0.75 and an aspartate aminotransferase:platelet ratio index >2 during screening or a FibroScan with a result of >12.5 kPa) but without signs of hepatic decompensation (i.e., ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal hemorrhage).

Patients presenting with any of the following criteria at screening were ineligible for this study: alanine aminotransferase >10 × upper limit of normal (ULN); aspartate aminotransferase >10 × ULN; direct bilirubin >1.5 ULN; platelets <50,000/μL; hemoglobin A1c >8.5%; creatinine clearance <60 mL/minute as estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault method; hemoglobin <11 g/dL for female patients and <12 g/dL for male patients; albumin <3 g/dL; and international normalized ratio >1.5 × ULN for patients without hemophilia or not receiving an anticoagulant that affects the international normalized ratio. Those with clinically significant electrocardiogram abnormalities at screening; coinfection with hepatitis B virus (hepatitis B surface antigen–positive) or human immunodeficiency virus; a history of or ongoing clinical hepatic decompensation, significant pulmonary disease, significant cardiac disease, or porphyria; non-HCV-related chronic liver disease (hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, cholangitis); or evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma were also excluded.

The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the initiation of any study-related procedures.

STUDY PROCEDURES

All patients received sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (400 mg/100 mg) once daily with weight-adjusted ribavirin (1,000 mg for patients with a body weight of <75 kg or 1,200 mg in patients with a body weight of ≥75 kg) in a divided dose twice daily for 24 weeks. Ribavirin dose adjustments were permitted per criteria specified in the product label.

Clinical visits were scheduled for all patients at screening; at the start of treatment; at the end of weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 of treatment; and at posttreatment weeks 4, 12, and 24. Cirrhosis status was documented using a liver biopsy, FibroTest and aspartate aminotransferase:platelet ratio index, or FibroScan. HCV RNA levels were quantified with the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV Quantitative Test, v2.0 for Use with the Ampliprep System (LLOQ of 15 IU/mL; Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ) using blood samples drawn at each study visit. HCV genotype and subtype were established using the Siemens VERSANT HCV Genotype INNO-LiPA 2.0 Assay (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany). Deep sequencing of the NS3, NS5A, and NS5B coding regions was performed on samples obtained from all patients at baseline and for patients with virologic failure at the time of failure. Sequences obtained at the time of virologic failure were compared with sequences from baseline samples to detect treatment-emergent RASs (15% cutoff). IL28B genotype was determined by polymerase chain reaction of the rs12979860 single-nucleotide polymorphism using sequence-specific primers and allele-specific TaqMan MGB probes.

Safety evaluations included monitoring for adverse events, clinical laboratory testing, physical examinations, and vital sign measurements.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with SVR 12 weeks after the end of treatment (SVR12). No inferential statistical analysis was planned. The sample size of approximately 150 patients was based not on sample size calculations but on an estimate of the number of patients who would be available from previous trials. The efficacy and safety analysis populations included all patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. The two-sided 95% exact confidence interval for the SVR12 rate within each treatment group and overall was calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS AND DISPOSITION

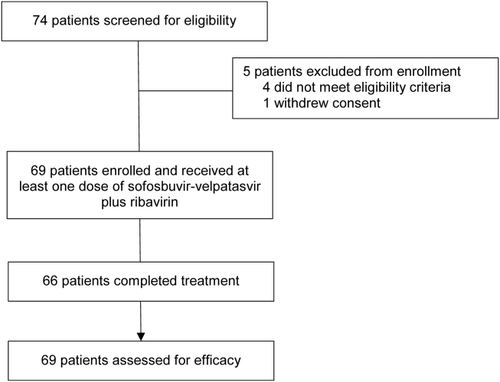

Of the 74 patients screened for this study, 69 enrolled and received study treatment (Fig. 1). Of the 5 patients who were screened but not enrolled, 1 withdrew consent and 4 did not meet eligibility criteria (3 had laboratory values outside the acceptable ranges and 1 was not able to comply with the dosing instructions).

In total, 37 patients were infected with HCV genotype 1 (32 with genotype 1a and 5 with genotype 1b), 14 with genotype 2, and 18 with genotype 3 (Table 1). Overall, most patients were white (88%) and male (77%). In all, 18 patients had compensated cirrhosis at baseline, 6 of 37 patients with genotype 1 HCV and 12 of 18 with genotype 3 HCV. None of the patients with HCV genotype 2 infection had cirrhosis at baseline. Among the 69 enrolled patients, 41 had previously received treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (27 with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir alone and 14 with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin) and 28 received sofosbuvir-velpatasvir with voxilaprevir. The duration of prior treatment ranged from 4 to 12 weeks, and the median interval between the end of the prior treatment regimen and the beginning of retreatment in this trial was 356 days, ranging from 101 to 600 days. One quarter of patients (n = 17) had received 12 weeks of prior treatment, while three quarters of patients (n = 52) had received prior treatment for 4-8 weeks per protocol-defined durations.

| Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir + Ribavirin for 24 Weeks (n = 69) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 57 (31-74) |

| Male, n (%) | 53 (77) |

| Mean body mass index, kg/m2 (range) | 28 (19-44) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 61 (88) |

| Black | 3 (4) |

| Asian | 2 (3) |

| Pacific Islander | 3 (4) |

| HCV genotype and subtype, n (%) | |

| 1 | 37 (54) |

| 1a | 32 (46) |

| 1b | 5 (7) |

| 2 | 14 (20) |

| 3 | 18 (26) |

| Mean baseline HCV RNA, log10 IU/mL (range) | 6.4 (4.4-7.4) |

| HCV RNA ≥800,000 IU/mL, n (%) | 54 (78) |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 18 (26) |

| Baseline alanine aminotransferase >1.5 × ULN, n (%) | 34 (49) |

| IL28B, n (%) | |

| CC | 23 (33) |

| CT | 46 (67) |

| TT | 14 (20) |

| Prior HCV treatment, n (%) | |

| Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir | 27 (39) |

| Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir + ribavirin | 14 (20) |

| Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir | 28 (41) |

| Prior velpatasvir dose, n (%) | |

| 25 mg | 28 (41) |

| 100 mg | 41 (69) |

| Duration of prior HCV treatment, n (%) | |

| 4-6 weeks | 25 (36) |

| 8 weeks | 27 (39) |

| 12 weeks | 17 (25) |

| Response to previous HCV treatment, n (%) | |

| No response | 1 (1) |

| Relapse or breakthrough | 68 (99) |

| Median time to retreatment, days (range) | 356 (101-600) |

ANTIVIRAL RESPONSE

By week 4 of treatment, HCV RNA was below LLOQ in 33 of 37 patients (89%) with HCV genotype 1 infection, 14 of 14 patients (100%) with genotype 2 infection, and 16 of 18 patients (89%) with genotype 3 infection (Table 2). By week 8, all patients who were still receiving treatment had HCV RNA <LLOQ, with the exception of 1 patient who discontinued therapy at week 8 due to nonresponse. This patient, a 62-year-old black man with genotype 3 HCV without cirrhosis, had declining HCV RNA from 7.08 log10 IU/mL at baseline to 2.03 log10 IU/mL by week 6; but his viral load increased to 2.19 log10 IU/mL by week 8, at which point treatment was discontinued per protocol for nonresponse. Pill counts suggested that this patient was 100% adherent to dosing.

| Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir + Ribavirin for 24 Weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genotype 1 (n = 37) |

Genotype 2 (n = 14) |

Genotype 3 (n = 18) |

Overall (n = 69) |

|

| HCV RNA <15 IU/mL during treatment | ||||

| Week 2 | 23 (62) | 10 (71) | 9 (50) | 42 (61) |

| Week 4 | 33 (89) | 14 (100) | 16 (89) | 63 (91) |

| Week 8 | 36 (97) | 13 (93) | 17 (94) | 66 (96) |

| HCV RNA <15 IU/mL after treatment | ||||

| Posttreatment week 12 (SVR12) | 36 (97) | 13 (93) | 14 (78) | 63 (91) |

| 95% confidence interval | 86-100 | 66-100 | 52-94 | 82-97 |

| By cirrhosis status | ||||

| Yes | 5/6 (83) | 0 | 9/12 (75) | 14/18 (78) |

| No | 31/31 (100) | 13/14 (93) | 5/6 (83) | 49/51 (96) |

| Virologic failure | ||||

| During treatment | 1 (3)a | 0 | 1 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Posttreatment relapse | 0 | 1 (7)b | 2 (12) | 3 (5) |

- a This patient stopped treatment at week 5.

- b The patient stopped treatment after 8 weeks of treatment due to incarceration.

- c One patient had HCV RNA <LLOQ at posttreatment week 4 (SVR4) and subsequently withdrew consent.

Overall, SVR12 was achieved by 63 (91%) of 69 patients: 36 of 37 patients (97%) with HCV genotype 1 infection (31 of 32 [97%] of those with genotype 1a infection and 5 of 5 [100%] of those with genotype 1b infection), 13 of 14 patients (93%) with genotype 2 infection, and 14 of 18 patients (78%) with genotype 3 infection. Of the 18 patients with cirrhosis, 14 (78%) achieved SVR compared with 49 of 51 (96%) without cirrhosis. SVR by genotype in patients with and without cirrhosis is shown in Table 2. Of patients who had received 12 weeks of prior treatment, 13 of 17 (82%) achieved SVR.

A total of 4 patients (6%) did not achieve SVR12 due to relapse. One 64-year-old white man with genotype 2b infection who had previously been treated with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir for 8 weeks had undetectable HCV RNA by week 2 of treatment but had to stop treatment after his week 6 visit when he was incarcerated. Upon release, this patient was found to have virologic relapse (HCV RNA 1,440,000 IU/mL). Two white male patients with genotype 3a HCV and cirrhosis relapsed at posttreatment week 4 after receiving the full course of treatment (both were 100% adherent to treatment according to pill count). Both had previously received 12 weeks of treatment, one of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir and the other of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin. Lastly, a 54-year-old white man with genotype 3a infection who had previously been treated with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks had HCV RNA <15 IU/mL from week 6 of treatment through posttreatment week 4. After receiving a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, he withdrew consent and was imputed a treatment failure.

Two patients had on-treatment virologic failure. One patient, a 62-year-old black male with HCV genotype 3a infection without cirrhosis who was a nonresponder during prior treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir, never achieved HCV RNA <LLOQ at any time during or after treatment. The other was a 67-year-old white man with genotype 1a HCV who discontinued treatment without consulting study staff after the week 2 visit, at which his HCV RNA was <LLOQ. He returned for the week 4 visit, at which his HCV RNA was 10,600 IU/mL. He resumed treatment but discontinued again 7 days later due an adverse event of irritability and subsequently withdrew consent.

One patient, a 31-year-old woman with genotype 1a infection who achieved SVR12, had detectable HCV RNA at posttreatment week 24. According to sequence analysis, the virus she was infected with at the time of virologic failure was distinct from what she was infected with at baseline, indicating reinfection rather than virologic relapse. Of note, this patient had also been documented to have achieved SVR after a previous HCV treatment course followed by reinfection.

RESISTANCE ANALYSIS

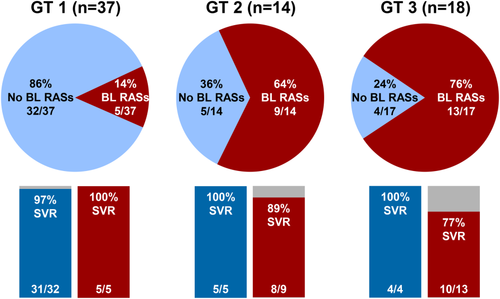

Using a 15% assay cutoff, 27 patients (39%) had baseline NS5A RASs. Baseline NS5A RASs were identified in 14% of patients with genotype 1 infection, in 64% of patients with genotype 2 infection, and in 76% those with genotype 3 infection (Fig. 2). The SVR12 rates among patients with NS5A RASs at baseline were 5 of 5 (100%) of those with genotype 1 infection, 8 of 9 (89%) of those with genotype 2 infection, and 10 of 13 (77%) of those with genotype 3 infection. The SVR12 rate among patients without baseline RASs was 40 of 41 (98%) overall and 4 of 4 (100%) for those with genotype 3 infection. Among patients with genotype 3 infection and the Y93H RAS at baseline, the SVR12 rate was 9 of 11 (82%).

The 2 patients with on-treatment virologic failure developed treatment-emergent NS5A and NS5B RASs. The patient with genotype 3a infection who had nonresponse had the emergent NS5A RASs A30R (in 4% of the viral population), L31F (3%), and Y93H (72%); and the patient with genotype 1a infection who had virologic rebound had an emergent NS5A RAS P32L (2%). NS5B nucleoside inhibitor RASs (not including S282T) emerged at low frequency (<2.5%) in both patients. Among the 3 patients who relapsed, 2 patients with genotype 3a had enrichment of NS5A RAS Y93H which was present at baseline and 1 of the 2 had emergent NS5A RAS L31M at a low level at the time of relapse. Both of these patients had received 12 weeks of prior treatment. One patient with genotype 2b had L31M at baseline and at relapse and no treatment-emergent NS5A RASs. None of the patients who relapsed and had available NS5B sequencing data had emergent NS5B RASs.

Of the patients who had 12 weeks of prior treatment, 14 of 17 had baseline NS5A RASs, with most having Y93H (12 of 14) and 2 with L31M/V. A majority of patients (12 of 14) with baseline NS5A RASs achieved SVR.

SAFETY

Overall, one patient (1%) discontinued all study drugs (sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin) due an adverse event (irritability) (Table 3); this patient subsequently withdrew consent from study participation, as described earlier. Ribavirin was discontinued in 3 other patients in response to adverse events of worsening cough, vomiting, and low mood; all 3 achieved SVR12. Nine patients interrupted or reduced dosing of ribavirin, all of whom achieved SVR12, except for 1 patient with HCV genotype 2 infection who was incarcerated and discontinued the study, as mentioned. The most frequent adverse events resulting in the modification or interruption of ribavirin therapy included hemolytic anemia (4%), nausea (4%), and fatigue (3%).

|

Overall (n = 69) |

|

|---|---|

| Any adverse event, n (%) | 61 (88) |

| Serious adverse event, n (%) | 3 (3) |

| Deaths | 0 |

| Discontinuation of all study drugs due to adverse events, n (%) | 1 (1) |

| Discontinuation of ribavirin only due to adverse events, n (%) | 3 (4) |

| Common adverse events (≥10% of patients in any treatment arm), n (%) | |

| Fatigue | 22 (32) |

| Nausea | 15 (22) |

| Headache | 12 (17) |

| Insomnia | 11 (16) |

| Pruritus | 10 (14) |

| Rash | 9 (13) |

| Irritability | 9 (13) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 (13) |

| Dyspnea | 6 (9) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (9) |

| Dyspepsia | 4 (6) |

| Hemolytic anemia | 4 (6) |

| Dry skin | 3 (4) |

| Grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities, n (%) | |

| Hemoglobin, <10 g/dL | 4 (6) |

| Lymphocytes, 350 to <500/mm3 | 1 (1) |

| Glucose (hyperglycemia), >250 to 500 mg/dL | 2 (3) |

| Lipase | |

| >3.0-5.0 × ULN | 1 (1) |

| >5.0 × ULN | 1 (1) |

| Total bilirubin (hyperbilirubinemia) | |

| >2.5-5.0 × ULN | 2 (3) |

| >5.0 × ULN | 2 (3) |

In total, 61 (88%) patients reported adverse events during the study, most of which were mild or moderate in severity. The most common adverse events were fatigue (32%), nausea (22%), headache (17%), insomnia (16%), pruritis (15%), rash (13%), irritability (13%), and upper respiratory tract infection (13%). Two patients had serious adverse events during the study: a 31-year-old white woman with genotype 1a HCV without cirrhosis had nephrolithiasis on day 59 of treatment, which resolved 3 days later, and a 54-year-old white man with genotype 3 HCV and cirrhosis was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma on posttreatment day 31.

Eight patients (12%) had grade 3 laboratory abnormalities, and 3 patients (4%) had grade 4 laboratory abnormalities. Grade 3 abnormalities in hemoglobin levels were detected in 5 patients (7%), lymphocytes in 1 patient (1%), glucose in 2 patients (3%), lipase in 1 patient (1%), and total bilirubin in 2 patients (3%). Grade 4 abnormalities in lipase were observed in 1 patient (1%) and total bilirubin in 2 patients (3%) secondary to ribavirin-induced hemolysis. None of the grade 3 and 4 elevations in lipase were accompanied by clinical evidence of pancreatitis.

Discussion

In this study, sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin for 24 weeks provided safe and effective retreatment for patients who had relapsed after prior treatment with DAA-only regimens containing sofosbuvir-velpatasvir, including those who had also received the NS3/4A protease inhibitor voxilaprevir. This regimen resulted in an overall SVR of 91%, highest in patients with genotype 1 infection (97%) and lowest in those with genotype 3 infection (78%). Among the patients who had received 12 weeks of prior treatment, 14 of 17 (82%) achieved SVR.

In contrast to NS3 and NS5B RASs, NS5A RASs appear to remain fit and persist following unsuccessful treatment with a DAA regimen that includes an NS5A inhibitor.5 As expected, there was a high prevalence of baseline NS5A RASs (40%) among the enrolled patients. The presence of NS5A RASs at the time of retreatment did not impact SVR in patients with genotype 1 or 2 infection but did reduce SVR rates in patients with genotype 3 infection. These data support the hypothesis that longer treatment duration and the addition of ribavirin can improve rates of SVR in patients with baseline RASs.

Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin for 24 weeks was safe and well tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with the known effects of ribavirin.10 While several patients experienced adverse events that led to modification and/or interruption of ribavirin, only 3 patients discontinued ribavirin, suggesting that ribavirin is tolerable in most patients.

Limitations of this study include its small sample size and single-arm, open-label design. Additionally, about one quarter of patients had previously been treated with a 12-week regimen, and the remaining three quarters of patients had previously been treated with a shorter-than-standard treatment regimen of 4, 6, or 8 weeks. Given the small sample size, caution should be used in interpretation of the results in subgroups.

In conclusion, sofosbuvir-velpatasvir plus ribavirin for 24 weeks may be an effective retreatment strategy for most patients who have failed prior NS5A-based HCV treatment.

Acknowledgment

Medical writing support was provided by Sameera Kongara, Ph.D., of AlphaBioCom, LLC, King of Prussia, PA, and funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc.