Statins decrease the risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus– and hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis: A population-based study

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

This study was supported by grants V102B-019 and V103B-034 from Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Abstract

Statin use decreases the risk of decompensation and mortality in patients with cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV). Whether this beneficial effect can be extended to cirrhosis in the general population or cirrhosis due to other causes, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection or alcohol, remains unknown. Statin use also decreases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with chronic HBV and HCV infection. It is unclear whether the effect can be observed in patients with pre-existing cirrhosis. The goal of this study was to determine the effect of statin use on rates of decompensation, mortality, and HCC in HBV-, HCV-, and alcohol-related cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis were identified from a representative cohort of Taiwan National Health Insurance beneficiaries from 2000 to 2013. Statin users, defined as having a cumulative defined daily dose (cDDD) ≥28, were selected and served as the case cohort. Statin nonusers (<28 cDDD) were matched through propensity scores. The association between statin use and risk of decompensation, mortality, and HCC were estimated. A total of 1350 patients with cirrhosis were enrolled. Among patients with cirrhosis, statin use decreased the risk of decompensation, mortality, and HCC in a dose-dependent manner (P for trend <0.0001, <0.0001, and 0.009, respectively). Regression analysis revealed a lower risk of decompensation among statin users with cirrhosis due to chronic HBV (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25-0.62) or HCV infection (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.93). The lowered risk of decompensation was of borderline significance among statin users with alcohol-related cirrhosis (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.45-1.07). Conclusion: Statin use decreases the decompensation rate in both HBV- and HCV-related cirrhosis. Of borderline significance is a decreased decompensation rate in alcohol-related cirrhosis. (Hepatology 2017;66:896–907).

Abbreviations

-

- CAD

-

- coronary artery disease

-

- cDDD

-

- cumulative defined daily dose

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- DDD

-

- defined daily dose

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HCVD

-

- hypertensive cardiovascular disease

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- ICD-9-CM

-

- International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition Clinical Modification

-

- KLF-2

-

- Kruppel-like factor-2

-

- NASH

-

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

-

- NHIRD

-

- National Health Insurance Research Database

-

- NO

-

- nitric oxide

Cirrhosis can be caused by various etiologies, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and alcohol intake. This condition leads to necroinflammation, fibrogenesis, and results in portal hypertension, hepatic dysfunction, and subsequent decompensation. Compared with compensated cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis significantly lowers the survival rate, as seen in patients with ascites with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding.1 To avoid or delay decompensation, early intervention to prevent or stabilize cirrhosis progression is required.2

Statins are a potential treatment option for lowering portal hypertension. This is done by modulating intrahepatic vascular resistance. In cirrhotic animal models, hepatic sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction with decreased nitric oxide (NO) production contributes to increased hepatic vascular resistance.3, 4 Statins improve the bioavailability of NO production, affecting sinusoidal endothelial cells, lowering hepatic vascular resistance, and thereby decreasing portal pressure.5-7 The use of statins has been found to decrease the rate of decompensation in patients with cirrhosis, as demonstrated in a retrospective investigation on medical records of patients with mainly nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).8 A similar effect of statin use was shown in HCV-related cirrhosis; as demonstrated in data from the US Veteran Affairs Clinical Case Registry.9 Regarding statin use in patients with chronic HBV infection, a dose-dependent reduction in the risk of cirrhosis and decompensation was shown in a population study from Taiwan.10 These previous reports are limited by their small scale (single health care system), restricted patient population (male veterans with HCV-related cirrhosis), or inclusion of patients with chronic HBV infection without cirrhosis. It remains to be investigated whether the beneficial effects of statin can be extended to patients with cirrhosis in the general population and patients with cirrhosis due to other causes (such as HBV or alcohol).

Statins are also able to inhibit tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis. This is done by blocking 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A reductase, the rate-limiting step of the mevalonate pathway.11 In addition, population studies have demonstrated that statin decreases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with HBV or HCV infection.12-14 However, the beneficial effect of statin use is realized primarily in patients who are in the chronic hepatitis stage; whether statins are also effective in decreasing HCC occurrence in patients who already have cirrhosis remains unknown.

Using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), we estimated the associations between statin use and the risk of decompensation, mortality, and HCC occurrence among patients with cirrhosis in general population and with different etiologies (i.e., HBV, HCV, and alcohol).

Materials and Methods

DATA SOURCE

We conducted a nested case-control study using a cohort from the Taiwan NHIRD. Taiwan's National Health Insurance is a mandatory universal health insurance program that was implemented in 1995 and offers comprehensive medical care coverage to all 23 million residents of Taiwan. The NHIRD is a comprehensive database drawn from the medical records of Taiwan's National Health Insurance. The patient information in the database includes: medical status, personal data, drug prescriptions, procedures, and the dates of both clinic visits and in-patient hospitalizations. The National Health Research Institute of Taiwan follows strict confidentiality guidelines to protect personal electronic data: it keeps the data anonymous and maintains the data as files suitable for research. The NHIRD has been used extensively in many epidemiologic studies in Taiwan.10, 12-16 The database contains highly accurate diagnoses of of major diseases, such as stroke (94%) and acute coronary syndrome (100%).17, 18 Database reliability is maintained by the Bureau of National Health Insurance of Taiwan, which performs quarterly reviews on a random sample of one of every 50-100 ambulatory and in-patient claims.

IDENTIFICATION OF PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS AND ETIOLOGIES OF CIRRHOSIS

We used a representative sample of 1 million people who were followed longitudinally from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2013. Patients aged ≥20 years with a diagnosis of cirrhosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition clinical modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 571.2, 571.5, and 571.6) were eligible for inclusion in the current study. The etiology of cirrhosis in the study cohort was identified as HBV (ICD-9-CM codes 070.2x, 070.3x, and V02.61), HCV (ICD-9-CM codes 070.41, 070.44, 070.7, 070.51, 070.54, and V02.62), and alcohol-related disease (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0, 571.0, 571.2, and 571.3). Patients with a history of any malignancy (ICD-9 codes 140-208, 230-231, and 233-234) other than HCC (ICD-9-CM code 155.0) were excluded from the study. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection (ICD-9-CM codes 042, 044, and V08) were also excluded.

STATIN EXPOSURE

We used defined daily dose (DDD) as recommended by the World Health Organization to measure the prescribed amount of statin (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical/Defined Daily Dose Index 2016; http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/). The DDD is a drug's assumed average maintenance daily dose that is consumed for its main indication. We calculated the sum of the dispensed DDD (cDDD) of all types of statins during the follow-up period. This served as an indicator of the duration of statin exposure. Patients with cirrhosis who had a cDDD ≥28 were categorized in the statin-user cohort. Patients with cirrhosis who did not take statins or who had a cDDD <28 were categorized in the statin nonuser cohort. The index date for each statin user was defined as the date of their first statin prescription. The first day of cirrhosis diagnosis was chosen as the index date for each statin nonuser. Patients who had a statin prescription before the date of cirrhosis diagnosis were excluded from the study. To examine the dose–effect relationship, we categorized the study cohort into three subgroups (<28, 28-365, and ≥365 cDDD).

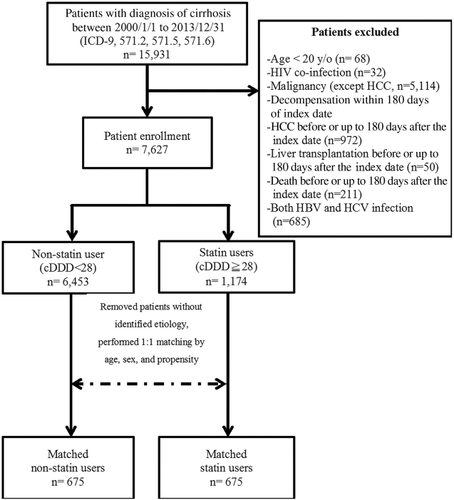

PROPENSITY SCORE AND MATCHING

We used a propensity score-matched design to minimize confounding variables. Propensity score matching was performed using a macro that we had developed and tested for SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). First, the program used logistic regression to score all patients with cirrhosis according to their statin treatment. Scoring involved 14 covariates, including age, sex, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertensive cardiovascular disease (HCVD), antiviral treatment, lipid-lowering drugs other than statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, aspirin, metformin, β-blockers, presence of nonhemorrhagic varices at the time of enrollment, follow-up duration, and cirrhosis etiology. These covariates might be relevant to our measured outcomes. Second, the macro selected the best match case for each of the statin users and nonusers. The best match was made according to the absolute value of difference between propensity scores. Third, each statin user and nonuser was matched by their propensity scores in a 1:1 ratio. The match was made using a greedy matching algorithm. A flow chart of patient identification and matching is shown in Figure 1. Our model had a c-statistic of 0.840, suggesting that the model's covariates are a good predictor of treatment status. The percentages of statin user matched to various decimals were as follows: match 8: 28/1350 = 2.1%, match 7: 0/1350 = 0%, match 6: 12/1350 = 0.9%, match 5: 74/1350 = 5.5%, match 4: 368/1350 = 27.3%, match 3: 560/1350 = 41.5%, match 2: 242/1350 = 17.9%, match 1: 66/1350 = 4.9%.

POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS

To adjust for the effects of comorbidities, we searched NHIRD for diabetes (ICD-9 code 250), CAD (410.xx-414.xx), and HCVD (401.xx-405.xx). We also searched for medications that might affect the measured outcomes (i.e., decompensation, death or HCC) in cirrhosis using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code. Drugs included: antiviral therapy (interferon, ribavirin for HCV, and nucleotide/nucleoside for HBV), metformin, aspirin, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (including captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, quinapril, benazepril, cilazapril and fosinopril), and other lipid-lowering drugs (clofibrate, bezafibrate, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate, nicotinic acid, and acipimox).

STUDY OUTCOMES

The primary outcome was decompensation, which included ascites (ICD-9-CM code 789.5) and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (ICD-9-CM code 567.23), hepatorenal syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 572.4), hepatic encephalopathy (ICD-9-CM codes 572.2, 348.30, 348.31, 348.39, and 348.89), and variceal bleeding (ICD-9-CM codes 456.0 and 456.20). The other outcomes included death or the development of HCC (ICD-9-CM code 155.0). Status after liver transplantation was also identified (ICD-9-CM code V42.7 and procedure code 50.5). To avoid potential immortal time bias,19 the outcomes were evaluated after a 180-day period of statin exposure.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

In between-group comparisons, independent t tests were used for continuous variables, and Pearson's χ2 tests were used for nominal variables. Cox regression analysis with covariates was used to estimate the relationship between statin use and the risk of decompensation, mortality, and HCC development in patients with cirrhosis. We performed the same analysis in subgroups with different etiologies of cirrhosis (i.e., HBV, HCV, and alcohol). The hazard ratios (HRs)20 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the outcomes were calculated in statin users compared with nonusers after adjusting for variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the outcomes in different study cohorts. The differences between the curves were tested with a log-rank test. For the dose–response relationship between statin use and decompensation, mortality, and HCC development, we assessed linear trends by entering the dose–response variable as a continuous variable in the conditional logistic models. The models were adjusted by potential confounders, including age, sex, cirrhosis with different etiologies, comorbidities (diabetes, CAD, and HCVD), medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, aspirin, other lipid-lowering drugs, antiviral drugs, and metformin), the presence of nonhemorrhagic varices at the time of enrollment, follow-up duration, and cirrhosis etiology. The Charlson comorbidity index score was used to determine overall health of patients with cirrhosis in both the statin user and statin nonuser groups.21 A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 15,931 patients with cirrhosis were identified. After excluding patients who met the exclusion criteria and those with cirrhosis with unidentified etiology, and after propensity score matching, 675 patients in each of the statin-user (≥28 cDDD) and nonuser groups were included. The demographic characteristics of statin users and non–statin users after matching are shown in Table 1. The mean time from year 2000 to the index date for statin users was 8.5 ± 3.5 years, which was similar to that in the non–statin user group (year 2000 to the date of enrollment, 8.6 ± 3.6 years). The Charlson comorbidity index was similar between statin user and statin nonuser groups (user vs. nonuser: 5.2 ± 2.3 vs. 5.5 ± 2.4; P = 0.323). Compared with nonusers, statin users displayed a significantly lower rate of occurrence of decompensation episodes (14% vs. 29%; P < 0.0001), mortality (9% vs. 18%; P < 0.0001), and HCC occurrence (6% vs. 10%; P = 0.0097) (Supporting Table S1). Multivariate analysis also revealed a significantly lower risk of decompensation (adjusted HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.30-0.50), mortality (adjusted HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34-0.63), and HCC development (adjusted HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35-0.76) among statin users (Table 2).

| Statin User | Statin Nonuser | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 675 | 675 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.365 | ||

| Men | 492 (73) | 476 (71) | |

| Women | 183 (27) | 199 (29) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 56.5 ± 11.2 | 57.5 ± 14.1 | 0.143 |

| Follow-up years, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 3.5 | 5.4 ± 3.6 | 0.667 |

| Cirrhosis subgroups, n (%) | |||

| HBV | 313 (46) | 292 (43) | |

| HCV | 146 (22) | 152 (23) | |

| Alcohol | 216 (32) | 231 (34) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 0.323 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 495 (73) | 510 (76) | 0.382 |

| CAD, n (%) | 334 (49) | 342 (51) | 0.703 |

| HCVD, n (%) | 546 (81) | 575 (85) | 0.042 |

| Nonbleeding varices at baseline, n (%) | 9 (1) | 7 (1) | 0.802 |

| Medication, n (%) | |||

| Antiviral treatment | 116 (17) | 116 (17) | 1.000 |

| Other lipid-lowering drug | 323 (48) | 312 (46) | 0.586 |

| ACEi | 383 (57) | 382 (57) | 1.000 |

| Aspirin | 409 (61) | 410 (61) | 1.000 |

| Metformin | 338 (57) | 332 (49) | 0.786 |

| β-blocker | 531 (79) | 536 (79) | 0.789 |

- Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; CAD, coronary artery disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCVD, hypertensive cardiovascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

| Decompensation | Mortality | HCC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||

| Statin nonuser (n = 675) | 196 (29) | 122 (18) | 69 (10) |

| Statin user (n = 675) | 95 (14) | 61 (9) | 42 (6) |

| aHR (95% CI) | 0.39 (0.30-0.50) | 0.46 (0.34-0.63) | 0.52 (0.35-0.76) |

| HBV-related cirrhosis | |||

| Statin nonuser (n = 292) | 90 (31) | 52 (19) | 37 (13) |

| Statin user (n = 313) | 38 (12) | 19 (6) | 27 (9) |

| aHR (95% CI) | 0.39 (0.25-0.62) | 0.39 (0.21-0.72) | 0.70 (0.40-1.25) |

| HCV-related cirrhosis | |||

| Statin nonuser (n = 152) | 42 (28) | 31 (20) | 22 (14) |

| Statin user (n = 146) | 21 (14) | 18 (12) | 9 (6) |

| aHR (95% CI) | 0.51 (0.29-0.93) | 0.96 (0.51-1.80) | 0.38 (0.14-1.04) |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis | |||

| Statin nonuser (n = 231) | 64 (28) | 39 (17) | 10 (4) |

| Statin user (n = 216) | 36 (17) | 24 (11) | 6 (3) |

| aHR (95% CI) | 0.69 (0.45-1.07) | 0.76 (0.43-1.35) | 0.78 (0.25-2.40) |

- All data are presented as the number of events (%) except for aHR (95% CI).

- Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

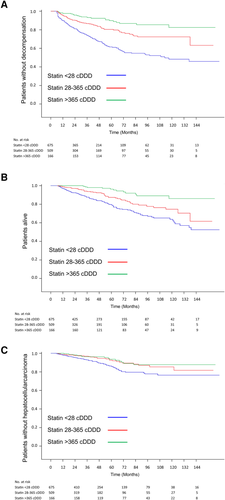

A dose–response relationship was observed between statin use and the risks of decompensation, mortality, and HCC occurrence (adjusted HRs [95% CI] with cDDD <28 vs. cDDD 28-365 and cDDD >365: decompensation, 1 vs. 0.50 [0.38-0.66] vs. 0.22 [0.14-0.35]; mortality, 1 vs. 0.61 [0.44-0.85] vs. 0.24 [0.13-0.44]; HCC, 1 vs. 0.56 [0.36-0.87] vs. 0.48 [0.26-0.86]; P for trend < 0.0001 in decompensation and mortality and P for trend = 0.009 in HCC) (Fig. 2).

The demographic data of the statin users and nonusers according to HBV-, HCV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis is shown in Table 3. Of the patients with HBV-related cirrhosis (n = 605), statin users had a significantly lower risk of decompensation (12% vs. 31%; P < 0.001) and mortality (6% vs. 19%; P < 0.001), but not HCC occurrence (9% vs. 13%; P = 0.114). (Supporting Table S2). The multivariate analysis revealed that in HBV cirrhosis, statin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of decompensation (adjusted HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.26-0.62) and mortality (adjusted HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.21-0.72), but not HCC occurrence (adjusted HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40-1.25) (Table 2).

| Etiology of Cirrhosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | HCV | Alcohol | ||||

| Statin user | Statin Nonuser | Statin user | Statin Nonuser | Statin user | Statin Nonuser | |

| No. of patients | 313 | 292 | 146 | 152 | 216 | 231 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 231 (74) | 198 (68) | 77 (53) | 73 (48) | 184 (85) | 205 (89) |

| Women | 82 (26) | 94 (32) | 69 (47) | 79 (52) | 32 (15) | 26 (11) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 56.3 ± 11.6 | 57.3 ± 14.4 | 61.5 ± 9.9 | 65.0 ± 13.8 | 53.3 ± 10.3 | 52.9 ± 11.8 |

| Follow-up years, mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 3.5 | 5.4 ± 3.5 | 5.4 ± 3.6 | 5.6 ± 3.6 | 5.4 ± 3.4 | 5.2 ± 3.7 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 224 (72) | 211 (72) | 115 (79) | 130 (86) | 156 (72) | 169 (73) |

| CAD, n (%) | 143 (46) | 138 (47) | 86 (59) | 97 (64) | 105 (49) | 107 (46) |

| HCVD, n (%) | 241 (77) | 239 (82) | 131 (90) | 136 (89) | 174 (81) | 200 (87) |

| Nonbleeding varices, n (%) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||||

| Antiviral treatment | 83 (26) | 97 (33) | 33 (23) | 19 (13) | NA | NA |

| Other lipid-lowering drug | 122 (39) | 107 (37) | 59 (40) | 73 (48) | 142 (66) | 132 (57) |

| ACEi | 162 (52) | 157 (54) | 99 (68) | 119 (78) | 123 (57) | 125 (54) |

| Aspirin | 171 (55) | 171 (59) | 107 (73) | 119 (78) | 131 (61) | 120 (52) |

| Metformin | 149 (48) | 146 (50) | 84 (58) | 78 (51) | 105 (49) | 108 (47) |

| β-blocker | 230 (73) | 222 (76) | 128 (88) | 132 (87) | 173 (80) | 182 (79) |

- Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; CAD, coronary artery disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCVD, hypertensive cardiovascular disease; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Among the patients with HCV-related cirrhosis (n = 298), statin users showed a significantly lower risk of decompensation (14% vs. 28%; P = 0.007), but not in mortality rate (12% vs. 20%; P = 0.063) and HCC occurrence (6% vs. 14%; P = 0.124) (Supporting Table S2). After the multivariate analysis, statin use in HCV-related cirrhosis patients was associated with a significantly lower risk of decompensation (adjusted HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.93) but no difference in mortality (adjusted HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.51-1.80) and borderline effect on HCC occurrence (adjusted HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.14-1.04) (Table 2).

In patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (n = 447), statin users had a significantly lower risk of decompensation (17% vs. 28%; P = 0.006) but a similar risk of mortality (11% vs. 17%; P = 0.102) and HCC occurrence (3% vs. 4%; P = 0.454) compared with nonusers (Supporting Table S2). After the multivariate analysis, statin use in alcohol-related cirrhosis was associated with a trend for lower risk of decompensation (adjusted HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.45-1.07) and no changes in the risk of mortality or HCC occurrence (adjusted HR [95% CI]: mortality, 0.76 [0.43-1.35]; HCC, 0.78 [0.25-2.40]) (Table 2).

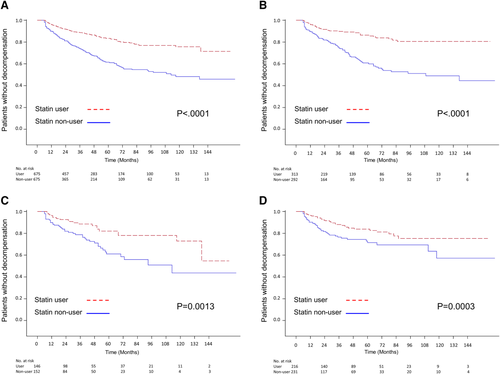

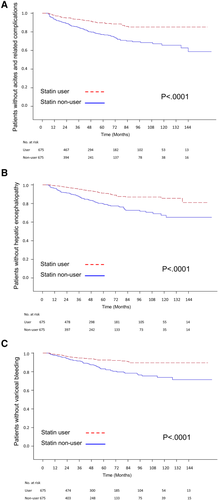

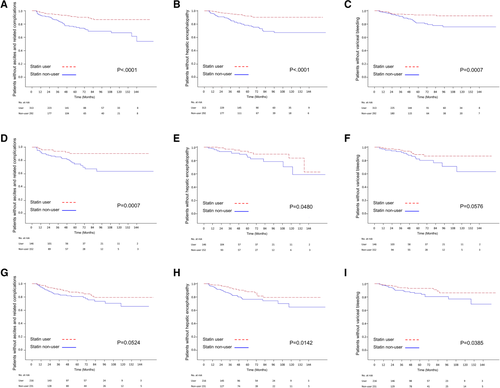

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis also demonstrated a significantly lower risk of decompensation during the 144-month follow-up for statin users in the total sample of patients with cirrhosis and in the subgroups of those with HBV-, HCV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis (Fig. 3). Further analysis based on different categories of hepatic decompensation indicated a significantly lower risk of ascites and related complications (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome), hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding in statin users compared with nonusers (Fig. 4) Subgroup analyses showed that statin users had a significantly lower probability of ascites-related events and hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis with all etiologies (Fig. 5A,B,D,E,H), except a borderline effect of ascites-related complications in the alcohol-related cirrhosis subgroup (Fig. 5G). A lower probability of variceal bleeding was noted in statin users with HBV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis (Fig. 5C,I), but borderline effect in HCV- related cirrhosis (Fig. 5F).

Around one-third of patients with HBV-related cirrhosis had received an oral antiviral agent or interferon therapy (statin users, 26.5% [83/313]; non–statin users, 33.2% [97/292]). After antiviral treatment, hepatic decompensation could still be observed at a similar rate among statin users and nonusers (15.7% [13/83] vs. 16.3% [29/97], respectively; P = 0.333). (Supporting Table S3)

Discussion

In this population-based and propensity score–matched study, we found that statin use may lower the risk of decompensation in a dose–response manner by around 50%-60% among patients with cirrhosis with chronic HBV or HCV infection, while having a borderline effect in alcoholic cirrhosis. The primary benefit of statin use were decreases in the risk of ascites-related complications and hepatic encephalopathy. Reduced risk of variceal bleeding could be observed in patients with HBV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis. Statin use was associated with significantly lower mortality (by approximately 60%), primarily in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis. Statin use also reduced overall HCC risk in patients with cirrhosis, but there was a lack of significance in subgroup analysis.

Few studies have been conducted to investigate the association between decompensation of cirrhosis and statin use. Kumar et al.8 conducted a study in a group of patients with cirrhosis with mainly NASH (43%) from the database of a single health care system, and statin usage was found to decrease the occurrence of hepatic decompensation. A recent study by Mohanty, et al.9 focusing on HCV-related cirrhosis data from the US Veteran Affairs Clinical Case Registry (primarily male patients with cirrhosis) found that statin usage is associated with a more than 40% lower risk of cirrhosis decompensation and death. Another recent placebo-controlled trial mainly in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (>70%) showed that adding simvastatin to β-blockers improved survival, but without a significant effect on the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage.22 These previous observations were limited by their inclusion of mixed etiologies of cirrhosis and restricted populations (patients from a single health system or male veterans). The current large-scale study is the first population-based study to address the association between statin use and risk of hepatic decompensation in cirrhosis with different causes. Our results extend the current knowledge and show that statin use can significantly decrease the risk of decompensation of cirrhosis in the general population in a dose–response manner among patients with cirrhosis due to chronic HBV or HCV infection, and possibly in alcoholic cirrhosis.

In patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, we also identified a dose-responsive effect of statin use in reducing the decompensation risk and a favorable effect in decreasing various types of decompensation, However, after regression adjustment, statin use could be demonstrated to result in only a borderline reduction in the risk of decompensation in patients who have alcohol-related cirrhosis. The underlying cause of this observation is unclear, but we suspect that continued alcohol consumption or poor statin adherence might have contributed to the finding. Abstinence remains the cornerstone of therapy for patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis who have received a liver transplant have reported a wide range of rates (10%-50%) of alcohol relapse with up to 5 years of follow-up,23 which could have a substantial effect on long-term survival.24 Consequently, continued alcohol consumption after the diagnosis of cirrhosis might counteract the statin effect and contribute to the borderline benefit. Similarly, poor compliance with statin use might be another factor leading to the borderline effect. Suboptimal drug adherence in antiretroviral therapy can be commonly observed in alcoholic use disorder and human immunodeficiency virus infection and has been associated with poor immunologic and virologic outcomes.25 We were not able to retrieve the data of either alcohol abstinence or the statin compliance from the NHRID. Future prospective trials are needed to clarify the statin effect in alcoholic cirrhosis.

Hepatic decompensation can be further divided into three categories: ascites with or without complication, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding. In a previous retrospective study focus on HCV-related cirrhosis, statin use was associated with a lower risk of variceal hemorrhage (adjusted HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19-0.78) and ascites (adjusted HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39-0.91). Statin use was also associated with the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (adjusted HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.29-2.90).9 In a prospective double-blind randomized trial composed of patients with mostly alcohol-related cirrhosis, adding simvastatin to the standard therapy did not have a beneficial effect on variceal rebleeding, new or worsening ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or against syndrome. However, simvastatin did have a beneficial effect on the survival of patients with Child-Pugh class A or B cirrhosis.22 In the current study, statin use seemed to provide benefits in reducing risk of most forms of the individual decompensation. Statin use decreased the development of ascites-related complication and hepatic encephalopathy in almost all cases of cirrhosis, except for a borderline effect in ascites-related complications of alcoholic cirrhosis. Statin treatment also decreased the risk of variceal bleeding in HBV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis, with a borderline effect in HCV-related cirrhosis. The underlying causes for these discrepancies among different studies are open to discussion. Further large-scale and prospective studies are needed to clarify this issue.

Multiple mechanisms could be associated with the beneficial effect of statins in decreasing decompensation risk among patients with cirrhosis. First, statins could facilitate the function of endothelial NO synthase and increase NO availability at the intrahepatic level, which in turn would contribute to intrahepatic vasodilatation and decreased intravascular resistance.5-7 These effects would not only reduce portal hypertension but also improve liver function by increasing hepatic inflow. Second, statin use could be associated with anti-inflammatory effects. Statins are able to decrease interleukin-6–mediated C-reactive protein, a product of hepatocytes and a predictor of poor prognosis in cirrhosis.26 Furthermore, in patients with chronic HCV infection, statin use is associated with a reduced risk of fibrosis progression, possibly through its anti-inflammatory effects.27 Third, statin use has been shown to abrogate liver fibrosis by enhancing the expression of Kruppel-like factor-2 (KLF-2), a factor primarily expressed in the endothelium, which confers endothelial protection against inflammation, thrombosis, and vasoconstriction.28-30 A recent animal study even showed that the overexpression of KLF2 in cirrhotic rats deactivates hepatic stellate cells and ameliorates dysfunctional hepatic endothelium. Overexpression of KLF, therefore, results in the improvement of liver cirrhosis as well as portal hypertension.31 Finally, statins can repress HCV activity both in vitro and in vivo.32, 33 In addition, the coadministration of statins has been shown to increase the opportunity for sustained virologic clearance with antiviral treatment,34, 35 which may also contribute to the observed effect.

In the current study, we also evaluated HCC occurrence among statin users in patients who had purely cirrhosis, because statins may affect the rate-limiting step in the mevalonate pathway to inhibit tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis.11, 36, 37 Previous studies have shown that statin use reduces the rate of HCC occurrence in a dose–response manner in patients who have chronic HBV and HCV infection but not cirrhosis.12, 13 We identified a chemoprotective effect of statin use in patients who already have cirrhosis. Nevertheless, the lack of a beneficial effect of statin use on reducing HCC occurrence was noted after subgroup analysis. Insufficient statistical power may have resulted in the insignificant findings in the subgroup analysis. This insufficiency is because our propensity score matching excluded around 500 statin users, contributing to the insignificant effect measured of statin use on HCC occurrence.

Our study has certain limitations. First, the effect of statin use on NASH, a major cause of cirrhosis in Western countries, was not evaluated. NASH usually coexists with obesity and requires histological examination. Because histological examination is used rarely to diagnose NASH in Taiwan, the ICD-9 coding in the NHIRD may not have been accurate enough for a detailed analysis. Thus, we did not include NASH-related cirrhosis for further analysis. Another possible confounder is the low rate of obesity/overweight in the Taiwanese population. Because body mass index is not recorded in the NHIRD, we were not able to incorporate it into the regression analysis. Second, the data on DDD obtained through NHIRD is based on official prescriptions and may not reflect the actual dose taken by patients. As already mentioned, we were not able to check for prescription adherence, because the NHIRD data are anonymous. We presumed that all medications were taken by the patients as prescribed, and this assumption could have overestimated the dosage actually ingested, leading to a biased association between statin use and decompensation occurrence. Additional confounders are self-medication and over-the-counter medication. Although this may introduce bias into the results, it remains unlikely, because medications listed in the current study were readily reimbursed by Taiwan's National Health Insurance. A third limitation is the lack of laboratory parameters (e.g., albumin and bilirubin levels) as covariates in the regression analysis. Nevertheless, we performed propensity score matching and multivariable analyses by including baseline nonbleeding varices, which would be partly adjusted for potential confounders. Finally, 79% of our patients with cirrhosis were on β-blockers, a medication that, when given together with statins, has demonstrated a synergistic effect in the lowering the portal pressure of patients with cirrhosis.38 Indications other than preventing variceal bleeding might have led to the high usage of β-blockers, because the results show that approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis had coexisting CAD and over 80% had coexisting HCVD (Table 1).

In conclusion, statin use decreased the decompensation rate in HBV- and HCV-related cirrhosis, whereas a borderline effect was noted in alcoholic cirrhosis. Improved survival was further noted in statin users with mainly HBV-related cirrhosis. Statin use may also reduce HCC occurrence among patients with cirrhosis. Statins may be considered an adjuvant therapy to prevent decompensation among patients with cirrhosis, but future prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings.

REFERENCES

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.