Are Hospital Pharmacists Ready for Precision Medicine in Nigerian Healthcare? Insights From a Multi-Center Study

ABSTRACT

Background

Precision medicine (PM) has taken center stage in healthcare since the completion of the genomic project. Developed countries have gradually integrated PM into mainstream patient management. However, Nigeria still grapples with wide acceptance, key translational research and implementation of PM. This study sought to explore the knowledge and attitude of PM among pharmacists as key stakeholders in the healthcare team.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in selected tertiary hospitals across the country. A 21-item semi-structured questionnaire was administered by hybrid online and physical methods and the results analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. A chi-square test was employed to determine the association of knowledge of PM and the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

Results

A total of 167 hospital pharmacists participated in the study. A high proportion of the participants are familiar with artificial intelligence (91.75%), Pharmacogenomics (84.5%), and precision medicine (61%). Overall, 38.9% of the pharmacists had a good knowledge while 13.2% had a poor knowledge of PM and associated terms. The level of knowledge did not correlate significantly with gender (X2 = 3.21, p = 0.201), age (X2 = 5, p = 0.27), marital status (X2 = 3.21, p = 0.201), and professional level (X2 = 6.85, p = 0.144). The most important value of precision medicine to hospital pharmacists is the ability to minimize the impact of disease through preventive medicine (49%) while a large portion are pursuing and or actively planning to pursue additional education in precision medicine.

Conclusions

There is a highly positive attitude toward the prospect of PM among hospital pharmacists in Nigeria. Education modules in this field are highly recommended as most do not have a holistic knowledge of terms used in PM. Also, more research aimed at translating PM knowledge into clinical practice is recommended.

Abbreviations

-

- EHR

-

- electronic health records

-

- MCPD

-

- mandatory continuing professional development

-

- PGx

-

- pharmacogenomics

-

- PM

-

- precision medicine

1 Introduction

The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 marked a transformative turn in medicine, leading to the emergence of precision medicine [1]. Precision medicine focuses on tailoring treatments to individual patients based on their unique genetic, phenotypic, or psychological factors [2]. It utilizes various biomedical knowledge domains such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, pharmacogenomics (PGx), metabolomics, and electronic health records to analyze diseases at different organizational scales [3-6]. This approach aims to provide the right treatment to the right patient at the right time, resulting in improved treatment decisions, reduced mortality rates, and decreased therapeutic costs [7].

Precision medicine has applications in various therapeutic settings like oncology, cardiac disease, diabetes, and rare diseases [3]. It holds promise in enhancing patient outcomes and transforming healthcare delivery models through advancements in technology such as digital therapeutics, epigenetics, and artificial intelligence (AI) [8].

Precision medicine approaches are being advanced in developed countries through initiatives such as the Precision Medicine Initiative in the United States [9], China's Precision Medicine [10], France's Genomic Medicine France 2025 [11], and Singapore's National Precision Medicine Program [12]. However, the situation in developing nations remains markedly different. In Africa, commendable efforts have been undertaken by research institutes such as the African Society of Human Genetics (AfSHG) [13], the H3Africa Consortium [14], and the African Genomic Medicine Training Initiative [15]. Their groundbreaking research aims to advance precision medicine on the continent. However, the critical challenge lies in translating this research into effective clinical practice [16]. The lack of a trained clinician workforce specialized in PM is a key factor. Previous surveys conducted outside Africa underscored the pivotal role of precision medicine knowledge, attitudes, and awareness in the adoption and dissemination of precision medicine [17-19].

In Nigeria, the most populous country in the continent, precision medicine approaches remain limited and fall short of adequacy. A Study conducted in Lagos showed that there are significant gaps in the preparedness of medical students, regarding precision medicine in Nigeria [20]. Despite the importance placed on learning about precision medicine, most students felt their education had not adequately prepared them for this field. Similar studies among nursing students also highlighted poor knowledge and readiness to integrate precision medicine approaches [21]. Efforts are being made to improve genomics education and competency among healthcare practitioners in the country [22]. To bridge these gaps, there is a need for more research and data applicable to indigenous populations in Africa. Additionally, translating genomic knowledge into diagnostics, genetic tests, or improved dosing algorithms is crucial for making precision medicine a reality in the country.

Given the absence of direct evidence regarding hospital pharmacists' involvement in precision medicine, and the growing recognition of the significance of precision medicine throughout the entire healthcare sector in Nigeria. This study aims to provide insights into the current landscape of hospital pharmacists in Nigeria regarding precision medicine. The study would evaluate their knowledge of associated terms, interest in expanding their knowledge, and willingness to undergo genetic testing. This valuable information can inform the development of targeted educational programs, address potential concerns, and facilitate the seamless integration of precision medicine into routine clinical practice.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Setting

This multi-centric study involved at least one tertiary hospital in Nigeria's six geopolitical zones. The North-Central Zone (Federal Medical Center Lokoja and Federal Medical Center, Abuja), Southwest Zone (Federal Medical Center Ebute Metta, Lagos, and Federal Teaching Hospital Ido-Ekiti), South-South Zone (Rivers State Teaching Hospital, Rivers), South-East Zone (Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Teaching Hospital, and Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Enugu), North-West zone (Federal Medical Centre, Gusau), North-East zone (Federal Medical Center Jalingo).

2.2 Study Design and Sampling Technique

This study was a cross-sectional survey assessing the hospital pharmacist's knowledge of precision medicine terminologies, perception of the knowledge, further interest in expanding their knowledge, and willingness to undergo genetic testing. Our sample comprised tertiary hospitals, selected due to their concentration of highly skilled healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, compared to primary and secondary care facilities [23] To ensure a comprehensive analysis, hospitals were chosen from all Nigerian geopolitical zones. Nine hospitals were ultimately based on their proximity and accessibility for researchers to distribute survey materials to the target population.

2.3 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The study included only licensed hospital pharmacists from the nine selected hospitals in Nigeria. Participation was voluntary, and no restrictions were placed on professional level, years of experience, or sociodemographic characteristics. This was performed to observe transient changes in knowledge at different levels. Pharmacy students who were still under training and other healthcare professionals were excluded from the study.

2.4 Sample Size Determination

Literature suggests that about 20% of the total pharmacist workforce in Nigeria practice in the hospital setting, mainly in the public sector [24]. This stands at a staggering 2000–2500 pharmacists considering the entire workforce. Our survey was distributed in 9 hospitals in at least each geopolitical zone of the country, and we expected a response rate of at least 15 pharmacists from each hospital.

2.5 Study Duration

This survey was conducted over 2 months from December 2023 to January 2024.

2.6 Data Collection Tool and Administration

A 21-question semi-structured survey was developed using adaptations from Ahmed et al., 2021 [17]. The three-sectioned survey was well-structured around four hypotheses: Hospital Pharmacists have a good awareness of precision medicine terminologies; The level of knowledge of the participants varies significantly based on their years of experience and other sociodemographic factors; Hospital pharmacists have supportive attitudes toward advancing the field of PM. Dr. Isah Abdulmuminu, a renowned clinical pharmacy researcher (Ph.D.), reassessed and approved the face validity of the survey tool [20]. Section one surveyed the respondent's sociodemographic characteristics. Their age (in years), gender (male or female), marital status (single, married), and professional level (senior-level, middle-level, and entry-level pharmacists) were assessed in this section. Section two assessed respondents' awareness of the terms Precision Medicine, Genomic Medicine, PGx', Omics-data', transcriptomics', proteomics', epigenomics', metabolomics', artificial intelligence', genomic sequencing, and electronic health records. Section three assessed the perceived knowledge of precision medicine and the attitudes of hospital pharmacists toward exploring the field of PM, assessing their interest in acquiring additional knowledge about PM, and their willingness to undergo genetic testing. The questions were disseminated both physically and online, using Google Forms.

2.7 Data Analysis

The questionnaire was assessed for completeness, and only questionnaires with complete responses were analyzed. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to summarize the data. Associations between the independent variables and sociodemographic characteristics were analyzed using a square test.

To determine the overall level of knowledge of terms associated with precision medicine, the 11-item knowledge questions were classified as “good,” “moderate” or “poor” based on the total score. “Yes” has a score of “1“ while “No” and ‘Do not Know’ both take a score of “0“ for a positive question and vice versa for a negative question. A total score equal to or less than 4 (out of a maximum possible score of 11) was considered “Poor Knowledge,” a score between 5 and 7 (out of a maximum possible score of 11) was considered “Moderate Knowledge” while a score of 8 and above (out of a maximum possible score of 11) was considered “Good Knowledge.”

2.8 Ethical Considerations

The Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Federal Medical Center, Abuja, scrutinized and approved the commencement of this study. An information sheet detailing the background and purpose of the study along with a consent form was shared with the volunteers before participating in the study. Respondents were also assured of the confidentiality of their information and no personal identification was sought in the study.

3 Results

3.1 Sociodemographics of Participants and Knowledge of Participants About Precision Medicine and Associated Terms

A total of one hundred and sixty-seven respondents were recruited for this study. These are pharmacists in various professional levels of nine selected tertiary health institutions in Nigeria. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The study population consisted predominantly of female participants (70.7%). In terms of age, the majority of participants fell within the age range of 26–40 years (69.5%), suggesting a relatively young to middle-aged cohort. Christianity represented the dominant religion among participants (79.4%), followed by Islam (19.4%) and other religions (1.2%). Additionally, the professional level of participants varied, with entry-level pharmacists comprising the majority (66.5%), followed by mid-level (23.8%) and senior-level pharmacists (9.8%).

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 118 | 70.7 |

| Male | 49 | 29.3 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 18–25 | 41 | 24.6 |

| 26–40 | 116 | 69.5 |

| Greater than 40 | 10 | 6.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 118 | 70.7 |

| Married | 49 | 29.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 131 | 79.4 |

| Islam | 32 | 19.4 |

| Others | 2 | 1.2 |

| Professional level | ||

| Senior level pharmacists | 16 | 9.8 |

| Mid-level pharmacists | 39 | 23.8 |

| Entry level pharmacists | 109 | 66.5 |

3.2 Level of Knowledge of Participants About Precision Medicine and Associated Terms and Relationship With Participants Sociodemographic

3.2.1 Hypothesis 1: Hospital Pharmacists Have a Good Knowledge About Precision Medicine and Its Associated Terms

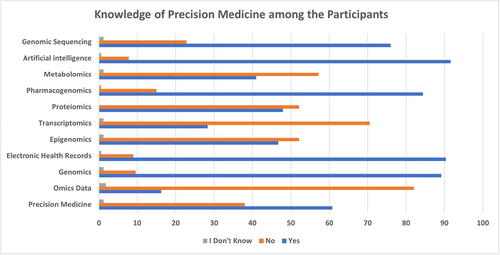

Figure 1 shows the participants' familiarity with various terms related to precision medicine. The results indicate varying levels of knowledge across different terms. Notably, a high proportion of participants reported familiarity with terms such as artificial intelligence (91.75%), PGx (84.5%), and electronic health records (90%). However, there are areas where knowledge appears to be less widespread. For instance, terms such as metabolomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics elicited lower levels of familiarity among participants, with much less than half of the respondents indicating awareness of these concepts. Furthermore, the term “precision medicine” itself yielded mixed responses, with 61% of participants indicating familiarity.

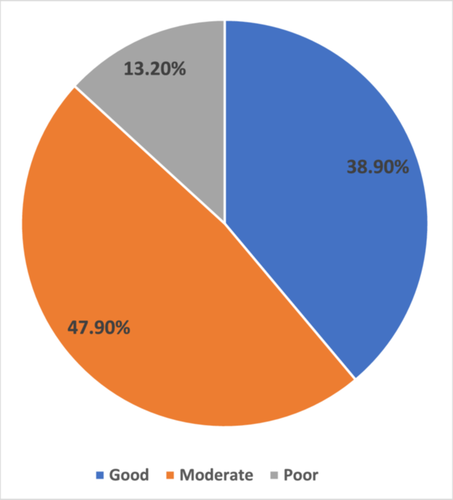

Overall, the level of knowledge of the pharmacist about precision medicine is good (38.9%). Nearly half (47.9%) of the respondents have a moderate knowledge of precision medicine while a paltry number (13.2%) admitted poor knowledge as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

| Level of knowledge | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Good | 65 | 38.9 |

| Moderate | 80 | 47.9 |

| Poor | 22 | 13.2 |

| Total | 167 | 100 |

3.2.2 Hypothesis 2: The Level of Knowledge of the Participants Varies Significantly Based on Their Years of Experience and Other Sociodemographic Factors

In Table 3, there is no marked difference in the knowledge levels between male and female Pharmacists. For the age group, there is a difference in knowledge between young Pharmacists and older ones (Good: 18–25 years (31.7%), 26–40 years (41.4%), greater than 40 years (40%). Though these differences are not significant (p = 0.201). Marital status and religion did not significantly affect the knowledge and perception of precision Medicine and related terms. The trend of knowledge in the professional -level category follows that of age closely. Senior level pharmacists took the good knowledge (9.5%) and moderate (6.3%) of precision Medicine compared with entry level pharmacists (good: 71.4%; moderate: 67.1%).

| Level of knowledge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Good | Moderate | Poor | X2 (p-value) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 39.8 | 50.0 | 10.2 | 3.21 (0.201) |

| Male | 36.7 | 42.9 | 20.4 | |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| 18–25 | 13 (31.7) | 24 (58.5) | 4 (9.8) | 5 (0.27) |

| 26–40 | 48 (41.4) | 53 (45.7) | 15 (12.9) | |

| Greater than 40 | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | 3 (30) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 47 (39.8) | 59 (50.0) | 12 (10.2) | 3.21 (0.201) |

| Married | 18 (36.7) | 21 (42.9) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 50 (38.2) | 63 (48.1) | 18 (13.7) | 0.67 (0.955) |

| Islam | 4 (12.5) | 14 (43.8) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Others | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Professional level | ||||

| Senior level pharmacists | 6 (37.5) | 5 (31.3) | 5 (31.3) | 6.85 (0.144) |

| Mid-level pharmacists | 12 (30.8) | 21 (53.8) | 6 (15.4) | |

| Entry level pharmacists | 45 (41.3) | 53 (48.6) | 11 (10.1) | |

- Note: Values significantly varied at p < 0.05.

3.3 Attitudes of Pharmacists Towards the Field of Precision Medicine

3.3.1 Hypothesis 3: Hospital Pharmacists Are Interested in Acquiring Additional Knowledge About Precision Medicine

Research Question 1: Are hospital pharmacists planning to pursue additional education or training in precision medicine?

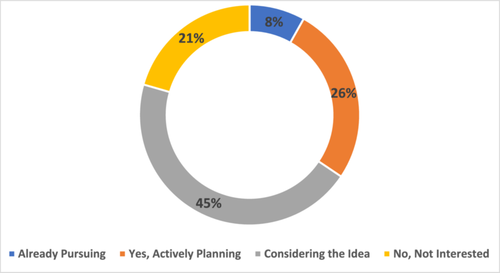

45% of pharmacists have not yet considered the prospect of pursuing additional education in precision medicine. 21% are not interested in pursuing further studies in precision Medicine while 26% are in active planning. A meager amount (8%) are already advancing their knowledge in this field. Overall, the pharmacists in this study are more inclined to seek more knowledge, experience, and capacity in the field of precision Medicine (Figure 3).

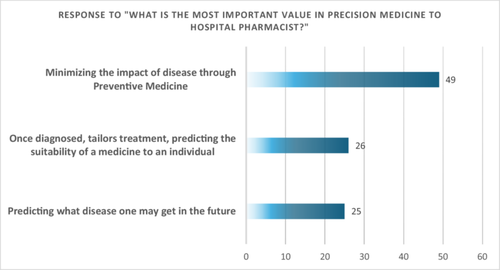

Research Question 2: What is the most important value of Precision Medicine to hospital pharmacists?

On the question of perception (the most important value of precision Medicine to hospital Pharmacists) as shown in Figure 4, 49% of the respondents believe in prevention as the goal of precision Medicine. A quarter (26%) believe in the ability of PM to cure (treatment) while another quarter think that it is intended for prognosis or to determine the risks of coming down with a disease.

Research Question 3: What Issues around precision medicine are of concern to clinical pharmacists?

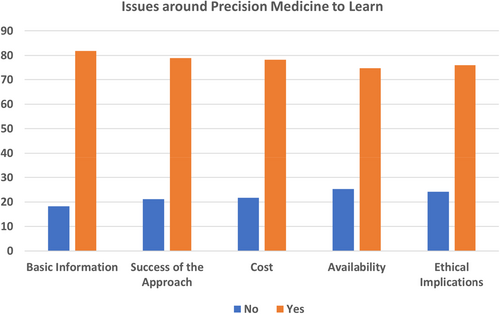

In Figure 5, More than 70% of pharmacists believe that issues like success, cost availability, and ethical implications are key in implementation of PM.

3.3.2 Hypothesis 4: Hospital Pharmacists Are Willing to Undergo Genetic Testing to Obtain Personalized Data

Research Question 1: Are hospital pharmacists willing to undergo genetic testing to obtain personalized data Table 4 shows the willingness of the pharmacists to implement the tenet of PM in their individual lives. Slightly more of the pharmacists are interested than not.

| Responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Questions | Not interested | Minimally interested | Moderately interested | Extremely interested |

| Do you want to know if you are at high risk of developing chronic diseases | 26 (15.6) | 42 (25.1) | 44 (26.3) | 45 (26.9) |

| Are you interested in undertaking a genetic test | 26 (15.6) | 32 (19.2) | 65 (38.9) | 44 (26.3) |

4 Discussion

Precision medicine is a king term in the parlance of modern healthcare delivery from diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of diseases [3]. PM is based on the genetic profiles of the individual. PM is used to forecast which course of treatment will work best for a given patient. Once broadly accessible, it can eradicate health inequities [25, 26]. Pharmacists employ PM in the use of patient-specific information to optimize drug selection, dosing, and treatment monitoring. The main tools of precision medicine are Big data, artificial intelligence, the various omics, environmental and social factors and the integration of these with preventive and population medicine. The study aimed to assess the level of knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of hospital pharmacists towards precision medicine and its associated terms. To the best our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind that has investigated this issue among hospital pharmacists in Nigeria.

4.1 Awareness and Perception of PM

The knowledge and awareness of precision medicine (PM) among hospital pharmacists in Nigeria spans a wide range, from poor to good, with a majority clustering in the moderate knowledge category. This was assessed based on their knowledge of PM-related terminology and their subjective perception of their own knowledge. Regarding the first metric, knowledge of terminology, over 50% was considered adequate knowledge, while less than 50% was deemed insufficient. Our survey revealed that more than half (50%) of participants demonstrated awareness of six terminologies, with “Artificial Intelligence (AI)” being the highest, while less than half were aware of the other five, with the lowest awareness being “omics data.”

Regarding the second metric, perception of knowledge, analysis of participants' self-reported knowledge identified subjective assessments that could influence their capacity for growth. A majority (80%) believed they had moderate knowledge of the field, while 38.9% believed they had a good grasp, and 13% thought they had poor knowledge. Globally, PM knowledge among healthcare workers is notably low in Africa [27, 28]. A recent Rwandan study by Musanabaganwa et al. examined knowledge levels and perceived challenges among healthcare workers. Less than half of participants expressed confidence in their PM knowledge and related terms [19]. The same study indicated that clinicians specializing in oncology and clinical genomics possessed a stronger grasp of PM theories and practices compared to others. Although this slightly diverges from our findings, the unique role of pharmacists as drug custodians within healthcare teams might explain their higher level of knowledge about tailored medicines. A comparable study examining knowledge and attitudes towards PM among Nigerian community pharmacists [29] found that less than half of respondents reported adequate pharmacogenomics (PGx) knowledge, amidst a high willingness for further training.

A clear correlation exists between healthcare professionals' knowledge and the emphasis placed on PM training during their education. Medical students at the University of Lagos exhibited limited knowledge of PM and their roles in genomic prescribing [20]. Similar findings were reported by Adejumo et al. for nursing students in Nigeria and by Makrygianni et al. for pharmacy students at the University of Patra, Greece, who did not consider themselves adequately prepared to practice PGx upon graduation [21, 30]. Targeted training is crucial to bridge the gap between academic knowledge and clinical practice. Successful integration of genetic and genomic evidence into clinical care hinges on training healthcare professionals and clinical researchers in genomic medicine.

Participants demonstrated the highest level of knowledge in genomic sequencing, artificial intelligence, PGx, genomics, and electronic health records (EHR). The recent surge in artificial intelligence, exemplified by OpenAI and its potential healthcare applications, might explain pharmacists' in-depth knowledge of PM [31]. Health information systems, the foundation of EHR, are essential components of a compliant and resilient healthcare system according to the World Health Organization (WHO). EHR adoption has been advocated for over a decade as a standard operating procedure in Nigerian healthcare. EHR enhances system efficiency and facilitates data storage and retrieval across various hospital units and regions, aiding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [32]. Despite its benefits, implementing a robust EHR in Nigeria has faced significant challenges, including poor data quality, incomplete data, inconsistent reporting, financial constraints, infrastructure deficiencies, and skilled personnel shortages. Electronic health records can generate large datasets containing various biomarkers (clinical and omics-based), laboratory, and radiological findings, which can be analyzed through machine learning algorithms to inform the management of specific patient populations [33].

PGx involves applying genomic variations to tailor medications for optimal clinical outcomes [4]. Pharmacists, with their deep understanding of drug action and metabolism, including associated enzymes and genes, are uniquely positioned to advocate for PGx in healthcare settings. Genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins significantly impact drug pharmacokinetics by influencing absorption, distribution, metabolism, or elimination. This study revealed high PGx knowledge among participants. While traditional PGx focuses on differentiating between rapid and slow metabolizers of drugs like isoniazid, the field has evolved to encompass both genetic and epigenetic factors influencing adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes. Tuesimi's thesis explored the perceptions and challenges of integrating PGx into Nigerian healthcare [34], identifying capacity building, ethical considerations, and public awareness as key factors for successful implementation.

The sociodemographic factors of the pharmacists in this study has a slight effect on their knowledge level, though it is statistically insignificant. Age group and professional levels are important determinants in this study. While older pharmacists possessed more practical experience, PM and AI have emerged as prominent fields in recent years. Younger pharmacists, often recent graduates completing internships or residencies, might not exhibit a causal relationship between higher knowledge and recent studies, as undergraduate pharmacy and medical students generally lack sufficient PM and PGx knowledge [20, 21, 30]. We categorized pharmacists as entry-level (interns and those with less than 2 years of experience), mid-level (less than 12 years of experience), and senior (more than 12 years of experience). Senior pharmacists appeared to lag in recent genomic and PM developments. This might be attributed to the relatively recent emergence of precision medicine and personalized medicine as major medical advancements, dating back to the publication of the first human genome sequence in 2003. Many senior and mid-level pharmacists with 15 or more years of experience lacked structured education in these areas, highlighting the need for continuous learning and upskilling. Postgraduate education can provide older pharmacists with a deeper understanding of the evolving PM field. Abubakar et al. reported higher PM knowledge and practice readiness among community pharmacists with postgraduate diplomas [29]. Our study however did not capture postgraduate qualifications and that may confound the causality of our findings.

Religion and belief systems are also important considerations on the acceptance and implementation of PM practices. A misconception of genetic alteration and manipulation in precision medicine and genomics assumes an interference in the exclusive reserve of God and may not sit well with religious and extremist groups [35]. These misconceptions abound regarding the implications and limits of genomic medicines including gene editing and therapy. Man, as argued is a whole organism in which catering for their health must ensure a delicate balance between their emotions, mind, beliefs, and the body. This in many ways addresses the ever-rising challenges of equity and the use of race in genomic studies [36]. Pharmacists in this study who are Christians had a higher knowledge of PM than those who profess other beliefs. While these differences did not reach statistical significance, they may reflect underlying sociocultural factors influencing access to education and exposure to precision medicine concepts within different religious communities. However, the imbalanced representation of Christians and pharmacists from other religions in this study could have impacted the results.

4.2 Attitudes of Participants Towards PM

Hypothesis 3 focused on the overall attitude of pharmacists toward PM and willingness to participate in its implementation and widespread acceptance. The penchant to pursue additional studies and upskilling is one of the fundamental hallmarks of professionals worldwide [37]. The pharmacist in this study reported a paltry 8% pursuing additional education while a whopping 45% have never considered the idea. This is very low considering the need for pharmacists to be in tune with the changing waves of practice around the globe. In Nigeria, the Pharmacist Council of Nigeria which regulates the practice of pharmacy rolled out the Mandatory Continuing Professional Development (MCPD) module for all licensed pharmacists to keep them abreast of advancements in pharmaceutical development and modern trends in pharmacy [38]. This is to enhance their skills in the process of providing pharmaceutical care. As reported above with community pharmacists, continued and postgraduate education has a profound impact on the skills and proficiencies of pharmacists. Abdullahi et al., assessed the attitudes and perceptions of MCPD among pharmacists across various work sectors [39]. A little above half (52%) participate regularly in professional development though finances, time, and work constraints remain major issues. Some professional, pharmacists, see embracing new advances as adding more burden to their already established job description, and thus the inertia to adapt to the changes persists.

The three foundational goals of PM are preventive medicine, diagnosis, and individually tailored treatment [3]. Our findings suggest that hospital pharmacists see the greatest value of precision medicine in preventive health than in diagnosis and tailored treatment. A common notion is that precision medicine is deterministic and more focused while preventive medicine is more community and public-health oriented. This dichotomy need not be if we clearly understand that most diseases arise from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. By employing precision medicine in a given population, key gene-related factors can be captured to address disease risks in that same population [40]. Bíró and authors called it “Precision prevention” [41]. The pharmacists in this study can therefore be said to understand the general benefits of PM in the wider population. It also reflects the more pronounced roles that pharmacists have taken all over the globe in public health campaigns and risk mitigation [35]. Precision diagnosis involves identifying patterns and establishing markers for accurate disease diagnosis within a population [42]. Tailored treatment, a cornerstone of PM, enables the application of interventions that maximize therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects based on individual or group genetic predispositions [4]. As therapeutics experts, pharmacists are well-positioned to excel in this area by leveraging pharmacogenomics for personalized treatment. The lower valuation of PM's diagnostic and treatment aspects in this study might indicate limited genomic medicine applications within Nigerian healthcare. It has already been discussed above that lack of skilled manpower, infrastructural deficits, and costs are major militating factors to full-scale implementation of PM in Nigeria and many African nations [20, 43].

Similar to the experience with vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic, individual-level participation in PM by healthcare professionals, particularly pharmacists, can foster public understanding and widespread acceptance. The active involvement of key healthcare stakeholders, including pharmacists, was instrumental in dispelling myths and conspiracy theories surrounding COVID-19 infections and vaccines [44]. Healthcare professionals should assume leadership roles in driving significant clinical practice changes and serve as advocates within the broader community. In our findings, more than two-thirds of the pharmacists were willing to check their predisposition towards diabetes mellitus as well as their individual genetic makeup. This willingness suggests a recognition among pharmacists of the potential benefits of genetic testing in informing personalized healthcare decisions and identifying potential health risks. By understanding their genetic predispositions, pharmacists may be better equipped to make informed lifestyle choices, engage in preventive measures, and tailor interventions to optimize their health outcomes. Moreover, pharmacists' willingness to undergo genetic testing emphasized their potential role as advocates for precision medicine and personalized healthcare approaches within the healthcare system. As healthcare professionals, pharmacists can leverage their knowledge and experiences to promote the integration of genetic testing into clinical practice and facilitate discussions with patients regarding the benefits and implications of genetic information. Studies on the willingness of pharmacists to adopt PGx and advocate it have been done robustly in the community setting while a paucity of studies remains in the hospital settings [29, 45]. In a US-based national study referenced above, Schwartz & Issa et al., discussed the role of hospital pharmacists in the adoption of PGx in clinical practice. They found clinical utility and or validity as a significant impediment in the update and use of PGx. While training is important, the participation of pharmacists in adopting PGx at a personal level is key to boosting their confidence [45].

4.3 Issues and Challenges Facing PM Implementation

The key challenges affecting the success of PM approaches as fully highlighted by participants falls under technical, regulatory, financial, educational, and ethical issues [46]. Doubts about the Human Genomic Project's feasibility, usefulness, applicability, and costs were a hot debate in the late 1980s just before it kicked off [47]. Saddled with limited resources and the urgent need for effective resource allocations, health policymakers are always skeptical about a new paradigm in health especially if the risks and benefits are not well understood. With the rising cost of healthcare across the globe, there is a lot of skepticism about who will bear the costs of all sequencing and genomic screening for patients if PGx is fully implemented [48]. This is especially true as the diseases with profound benefits from genomics including cancer and diabetes carry the greatest burden around the globe. In a scoping review by [49], PM aims to reduce the cost of treatment for many chronic diseases thus conferring on it the cost-effectiveness badge. Cost-effectiveness is not just about lesser costs but also which treatment/interventions offer the best outcomes within the same range of budget. Prevalence of the genetic condition in the target population, costs of genetic testing, and the probability of complications or mortality will greatly affect the extent of this cost. Though this is a pre-COVID-19 analysis, the impact of COVID-19 on the outlook and funding availability of PM remains to be considered. A meta-analysis 4 years on is still in doubt about the cost-effectiveness and value for money of precision medicine as conflicting evidence abounds between publicly funded and commercially funded studies [50]. Even though progress has been made in the African continent through Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) with its inception in 2012, a funding gap still exists in many of its projects [43].

Another challenge encountered is the technical complexity of implementing PM. PM is data-driven and necessitates the utilization of substantial volumes of heterogeneous data, ranging from genetic to clinical information. A primary obstacle lies in the integration of these diverse data sources into a unified framework for analysis. Exacerbating this issue is data compartmentalization and fragmentation within healthcare systems, which can hinder comprehensive patient assessments. Additionally, ethical considerations surrounding the use of patients' genomic data in PGx pose a critical challenge that may curtail widespread adoption. Other obstacles include a dearth of education and expertize in related fields such as genetics, genomics, translational sciences, bioinformatics, and biomedical engineering [51], disparities in genetic data between Africa and the rest of the world [52], primarily attributable to the under prioritization of genomic studies in Africa [53], and economic barriers and financial constraints that significantly impact healthcare decisions and impede proactive healthcare seeking behaviors [54].

Religious affiliations as noted earlier on coupled with illiteracy might fuel these concerns further in Africa and Nigeria. This is consistent with reports by Siamoglou et al. [55] and Mahmutovic et al. [56] among pharmacy and medical students. Schwartz & Issa et al. [45], also noted a significant concern about unauthorized access to patient data in their work among hospital pharmacists. Patient privacy and anonymity stand in jeopardy with the proliferation of genetic information in PM. This can become a biological weapon in the wrong hands. With the advances in genomic medicine being championed by private corporate entities in Nigeria and Africa, this finding highlights a need to safeguard trust and trustworthiness in informed consent and the subsequent use and dissemination of participants' genomic data by corporate bodies by ensuring the highest ethical standards are maintained. How do we handle discrimination in a society like Nigeria with a widened gap in socioeconomic class and ethnic lines? [20]. These findings highlight the multifaceted challenges associated with integrating precision medicine into clinical practice, including feasibility and ease, cost and resource allocation, ethical considerations, and societal acceptance. Though the issues of knowledge gaps and adequate skilled manpower, as well as an infrastructural deficit, were not well captured in these challenges, addressing these concerns is crucial for the successful implementation and adoption of precision medicine approaches within healthcare settings.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, this study elucidated the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of hospital pharmacists toward precision medicine. While a substantial proportion demonstrate moderate knowledge levels, opportunities exist for further education and training to enhance proficiency in this evolving field. Pharmacists exhibit a proactive stance towards acquiring additional knowledge and integrating genetic testing into their practice, highlighting their pivotal role in advancing precision medicine initiatives. Future research should focus on targeted interventions to address knowledge gaps and explore the impact of enhanced pharmacist engagement on patient outcomes in the context of precision medicine.

Author Contributions

Goodness C. Nwokebu: conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), methodology (lead), supervision (supporting), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Shadrach C. Eze: formal analysis (equal), visualization (lead), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Prince J. Meziem: writing – original draft (equal). Catherine C. Eleje: writing – original draft (equal). Emmanuel I. Ugwu: methodology (supporting), writing – original draft (supporting). Manuella O. Dagogo-George: writing – original draft (equal). Favour O. Orisakwe: writing – original draft (equal). Gerald O. Ozota: writing – original draft (supporting), writing – review and editing (lead). Abdulmuminu Isah: supervision (lead), writing – review and editing (supporting).

Acknowledgments

We extend our profound gratitude to Pharm Oluchi Nwachuya, Pharm Ngozi Obute, and Pharm Tijani Umar for their unwavering support, encouragement, and guidance throughout this research. Additionally, we are grateful to all those who contributed to data collection. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Ethics Statement

This study involved the use of human subjects, so approval was sought and obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Federal Medical Center, Abuja (Reference Number: FMCABJ/HREC/2024/133).

Consent

An information sheet detailing the background and purpose of the study, along with a concert form, was shared with the volunteers before participating in the study. Respondents were also assured of the confidentiality of their information and no personal identification was sought in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.