China's aging population: A review of living arrangement, intergenerational support, and wellbeing

Abstract

China's rapid population aging and remarkable family-level changes have raised concerns about the weakening of its family-based elderly care. The last decade indeed has seen a clear departure from multigenerational living to alternative living arrangements such as living with spouse only and solo living. However, ample evidence suggests that Chinese families have demonstrated considerable resilience amidst profound sociodemographic changes. This review article highlights the importance of government–society cooperation in meeting the social challenges of population aging. A key factor is the persistient filial piety norms, which enable children living far or close, migrant or nonmigrant, to rearrange financial, instrumental, and emotional support to aging parents. Equally important is the step-in of the government to share elderly care responsibilities, provide support through deepening pension and healthcare reforms, and implement the active and healthy aging agenda. How the two factors play out over the next decade and beyond will have profound implications on the living arrangement, intergenerational support, and wellbeing of older adults in China.

Abbreviations

-

- ADL

-

- activity of daily living

-

- CFPS

-

- China Family Panel Studies

-

- CGSS

-

- China General Social Survey

-

- CHARLS

-

- China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

-

- CLHLS

-

- Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey

-

- FYP

-

- Five Year Plan

-

- TFR

-

- total fertility rate

1 INTRODUCTION

Research on China's population aging and accompanying social challenges has proliferated in the past decade. Driving factors include growing interest in China's aging experience as a case of “getting old before getting rich” and availability of high-quality data to conduct methodologically rigorous and internationally comparable research. With the benefit of hindsight, the past decade has witnessed a very low fertility level in China, surprisingly strong rural-to-urban and city-to-city migration flows, and a steady decline in family sizes and multigeneratioal households.1 No other societies have experienced such rapid and large-scale sociodemographic changes, making China a valuable case for studying the social implications of population aging.

The past decade has also seen major policy responses to changing demography and emerging challenges. The multitrillion healthcare reform, launched in 2009 was implemented in the 2010s [1]. Following the introduction of the pension scheme for rural residents in 2009, a similar scheme was rolled out in 2011 for urban nonworking population [2]. While the healthcare and pension reforms do not target specific age groups, older adults as pensioners and more frequent users of healthcare services are arguably the largest immediate beneficiaries. China has also announced programs and initiatives designed for its senior citizens, including the long-term care insurance piloted in 16 cities in 2016, and the 13th Five Year Plan (FYP) for Healthy Aging (2016–2020), the first of its kind, followed by the 14th FYP for Healthy Aging (2021–2025) [3-5]. The healthy aging plans have identified key domains for policy action, encompassing health promotion and education, public health service, medical service system, integrated medical care and social care, supportive environment, and professional workforce. These unprecedented policy responses make China a fertile ground to study what works to what extent in tackling the challenges of population aging.

High-quality survey data enable scholars from different disciplines to advance China-focused aging research in a leap forward manner in recent years. Widely used data include CFPS (China Family Panel Studies), CGSS (China General Social Survey), CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study), and CLHLS (Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey), which allow scholars to delve deep into factors shaping the wellbeing of Chinese older adults and publish evidence-based studies in top academic journals. Symposiums and special issues examining the processes and implications of China's population aging have also appeared [6, 7].

Noting the tremendous advancement in China-focused aging research, this article aims to provide a synthetic review of how living arrangement and intergenerational support transform in the context of profound demographic changes and substantial government policy interventions, and how such transformations affect the health and wellbeing of Chinese older adults. The surveyed literature consists of published studies in leading journals of aging research that employ one of the survey datasets described above to examine living arrangement or intergenerational support in China in the past decade. The existing literature presents ample evidence that Chinese families are remarkably resilient during the transition from multigenerational living to diverse forms of living, including living with spouse only and living alone. Nonetheless, this review article suggests two areas where more research is needed. First, while efforts have been made to analyze the health effects of living with spouse only and living alone as opposed to multigenerational living, most studies focus on the subjective wellbeing such as happiness and life satisfaction. There is a need to examine a fuller set of health indicators. Second, most previous studies focus on family-level resources and coping strategies. More research is needed to analyze how the factor of government policy interventions plays out when families make care decisions and rearrange intergenerational support and how the government–society cooperation can be more effective in fostering healthy aging.

2 LIVING ARRANGEMENT AND INTERGENERATIONAL SUPPORT

A growing body of research on the health and wellbeing of Chinese older adults has emphasized the importance of living arrangements and intergenerational support. The cultural explanation argues that conforming to the prevailing norms—filial piety in the Chinese context—promotes subjective welling and therefore produces a health-enhancing effect, while any discrepancy between expected and actual living arrangement or intergenerational support is likely to hurt older adults' health and wellbeing [8]. A more general argument highlights the many benefits of coresident living arrangement, from providing daily assistance to giving emotional support, which in turn enhance geriatric health [9].

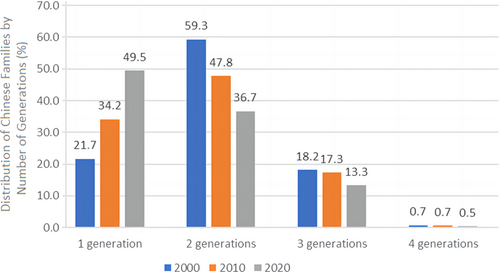

China's departure from multigenerational living is widely seen as a social challenge, a trend that has accelerated in the past decade. Figure 1 presents the percentage of Chinese families with varying numbers of generation between 2000 and 2020. Two-generation households were dominant in 2000 and 2010 with a share of 59.3% and 47.8%, respectively, and three-generation households were quite stable at 18.2% in 2000 and 17.3% in 2010. However, the landscape was drastically different in 2020. With a share of 49.5%, one-generation households became the prevailing type, while three-generation households decreased to 13.3%.2

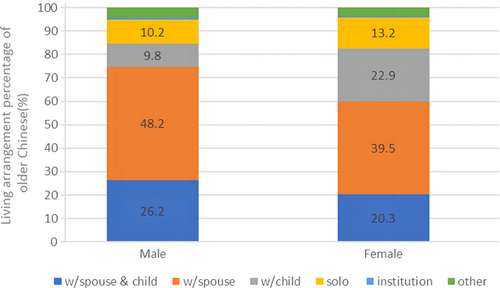

For the first time, China surveyed the living arrangement of its older population (aged 60 and above) in 2020. According to the 2020 census data, living with a spouse is currently the dominant form of living arrangement at 43.7%. Living with spouse and child is a remote second at 23.1%, followed by living with a child (16.6%). Solo living accounts for another 12%. Institutional living constitutes a very small share of 0.7%, far below the government target of 3%. Not surprisingly, there are notable gender differences in living arrangement (see Figure 2). A higher percentage of men live with spouse and child or live with spouse only. In contrast, a higher percentage of women live with child or live alone, due to the fact that women tend to outlive men.

Recent studies have examined factors that shape the living arrangement of Chinese families, paying particular attention to the process of dynamic adjustment concealed in either aggregate macro-data or cross-sectional micro-data. Using four waves of CLHLS data collected in 2005–2014, Gu et al. [10] find that about 15% of the interviewees aged 65 and above in the sample lived alone. Moreover, the transitions into and out of solo living were surprisingly frequent. Notably, over an average 3-year survey interval, more than 40% of solo-living older adults had moved to either multigenerational living or living with spouse only. Their analysis suggests that three types of factors—socioeconomic status, care needs, and living preferences—shape Chinese older adults' living arrangement. Specifically, homeownership and preference for solo living increased the likelihood of moving from non-solo living at time point 1 (T1) to solo living at time point 2 (T2) or remaining in solo living versus remaining in non-solo living. By comparison, family income and care needs (due to ADL disabilities or cognitive impairment) reduced the likelihood of either remaining in solo living or transitioning into solo living, suggesting that while Chinese families dynamically adjust living arrangements over the life course, some families are better able to adjust than others (in the absence of external help).

The rise of non-coresident living has raised concerns about intra-family support for aging parents. The existing literature has classified the flow of support from children to parents into one of three types, namely financial, instrumental, and emotional [11-14]. Available evidence suggests that the past concerns have underestimated the ability of Chinese families to cope with non-coresident living by re-arranging intergenerational support. New coping strategies include the growing prominence of spousal care-giving [15], extensive support to non-coresident parents by children living nearby [16, 17], significant financial contributions to left-behind parents from migrant children [18, 19], and the step-in of adult daughters to provide financial and emotional support to their natal parents [11, 20, 21].

Using CHARLS data collected in 2011–2012, Gruijters [15] compares care-giving to parents in three different living arrangements: coresident living with a child or child-in-law, independent living with at least one child living in the same community, and independent living without children in either the household or community. He focuses on a particular vulnerable group—functionally impaired older adults in rural China. Among them, roughly one out of seven did not receive any instrumental help. This study finds that independent living per se does not disadvantage older adults if spousal care-giving is available. Having a child in the same community does not provide extra benefit if parents are cared for by their spouse. By comparison, proximity to children becomes important for single parents, in which case spousal care-giving is not possible. Overall, the spouse has become a primary source of care-giving for older adults, while children step in as care-givers when the spouse is no longer available to perform this role.

A new line of research has begun to examine how geographic proximity affects non-coresident children's support to parents as opposed to coresident children. Not surprisingly, longer living distance leads to less frequent visits and lower levels of instrumental support from adult children to their parents. However, children living farther away often provide more financial support [11, 16, 17]. Research in this line suggests that Chinese families tend to follow the model of compensation in allocation of care responsibilities among adult children, particularly between migrant and nonmigrant children [19]. Those providing more instrumental support are expected to provide less financial support. Conversely, those providing less instrumental support are expected to provide more financial support.

Recent studies have also analyzed the role of values and norms in shaping living arrangements and intergenerational support. Ample evidence suggests that filial piety remains alive and viable in China, even though some other traditional norms such as patrilineal values are waning [13, 22, 23]. The core or essence of filial piety—xiao and jing, or supporting and respecting parents—has persisted well, while the expression of filial piety has been changing to suit the new demographic realities. There is increasingly less emphasis on adult children co-living with parents as a preferred living arrangement [24]. Meanwhile, daughters play a no less significant role than sons in supporting their natal parents [11]. Apart from filial piety, norms such as altruism and reciprocity also affect the pattern of intergenerational support. Altruistic support is channeled to family members who have greater needs yet limited or uncertain ability to return the favor. Parents with less education are more likely to receive financial support from their adult children [25]. Likewise, parents who have ADL disabilities or are widowed are more likely to co-reside with their children [26, 27]. By comparison, norms of reciprocity lead to bilateral exchange of care and support across generations, evidenced in the finding that parents are more likely to receive financial transfers from children if they provide various forms of support to their children, including housework, child-care, or wedding gifts [25].

3 EFFECTS ON HEALTH AND WELLBEING

A growing body of research has explored how living arrangements and intergeneration support affect the health and welling of Chinese older adults. In part driven by data availability, the subjective dimensions of health and wellbeing have received unprecedented attention, including psychological and mental health [9, 28-31], social security [32-35], and happiness and life satisfaction [8, 10, 36-39].

Along with growing attention to the subjective dimension of health and well-being, researchers have brought preference into the analytical framework as an important factor mediating the effect of living arrangement and intergenerational support on the health and wellbeing of older Chinese. Preference for a particular type of living arrangement or particular care-givers reflects cultural norms, care needs, and living experiences [24, 40]. According to the discrepancy theory, unmet preferences have a negative impact on the wellbeing of older adults [41].

In an analysis of the China sample from wave 1 of the WHO Study on Global Aging and Adult Health, Han et al. [8] find that living with one's spouse is associated with a higher level of subjective wellbeing than living in a multigeneration household, which in turn is associated with a higher level of subjective wellbeing than solo living. Resources are found to play a mediating role. Living with spouse only is associated with a lower level of subjective wellbeing if the respondent is in the bottom third income distribution, compared to those in the high-income group (whether living alone or not). Chen [24] explicitly analyzes the effects of living arrangement concordance—having a match between preferred and actual living—on the subjective wellbeing of elderly Chinese. Based on CHARLS data collected in 2011, he finds that realized preference enhances the subjective wellbeing measured by depressive symptoms and happiness to a greater extent than the traditional multigenerational living.

Using longitudinal data, some scholars take a step further to examine the complex relationship between living arrangement transitions and health of older Chinese. Drawing data from four waves of CLHLS surveys conducted in 2005–2014, Gu et al. [10] find that while multigenerational living reduces the likelihood of feeling lonely and unhappy compared with solo living, solo living is associated with a lower risk of ADL disability and mortality. The multifaceted relationship between living arrangement and health has a great deal to do with the selection process. Those with greater care needs are more likely to move into multigenerational living while those in better health and prefer solo living are more likely to transition into solo living. Meanwhile, those who are economically disadvantaged tend to end up in solo living involuntarily, making the solo living group heterogeneous in terms of socioeconomic status and living arrangement concordance (or discordance).

Using the same data as Gu et al. [10], Sun and Zimmer [39] focus on the comparison between coresiding with children and non-coresiding with children, factoring in living arrangement concordance (or discordance). Their analysis shows that a sizable portion of older Chinese have changed their actual living arrangement from T1 to T2—11.8% from non-coresident to coresident living, 10.7% from coresident to non-coresident living, in contrast to 32.9% remaining in coresident living and 44.7% remaining in non-coresident living. In terms of living arrangement concordance, 48.9% are consistently matched between T1 and T2, 12.8% consistently unmatched, while 18.3% move from unmatched to matched, and 20.0% from matched to unmatched. The authors present several illuminating findings. First, preference is an important determinant of life satisfaction. Having a match between preferred and actual living arrangements increases life satisfaction, regardless of actual living arrangement. Second, coresiding with children improves life satisfaction, net of the effect of matched preference. Third, the effect of matched preference and coresident living on life satisfaction changes with age, albeit in an opposite direction. The protective effect of matched preference declines with age, while that of coresident living increases with age.

Living arrangement is often a family decision involving deliberations on intergenerational care-giving (not only from children to parents, but also from grandparents to grandchildren). Liu and Chen [38] seek to disentangle the relationship between intergenerational care-giving, living arrangements, and life satisfaction of adults in mid and later life in China. Based on the 2011 and 2013 waves of CHARLS data, they find a higher level of life satisfaction among grandchild caregivers than non-caregivers. Notably, grandchild caregivers living with grandchildren enjoy higher life satisfaction even their adult children are not coresiding with them. The finding of psychological benefits of grandchild caregiving within skipped-generation households is in stark contrast to the grandparenting literature in some western countries such as the United States, where grandchild care-giving in skipped-generation households leads to an array of health problems. Further analysis shows that women and rural residents enjoy psychological advantages over men and urban residents in grandparenting within skipped-generation households, suggesting that in the Chinese context, grandchild caregiving is not necessarily a health-damaging stressor, but a self-fulfilling activity and an expression of family solidarity, which produces health-enhancing effects. Nonetheless, Song et al. [29] find that large-scale out-migration, a cause of skipped-generation households in the countryside, has a detrimental effect on the mental health of the “left-behind” in less wealthy villages (but not in wealthy villages).

Overall, research on living arrangements and intergenerational support in the past decade provides strong evidence that the decline of multigenerational living per se does not necessarily reduce care support to the aging parents and hurt their health. Chinese families by and large are capable of adjusting expectations, shifting preferences, and renegotiating care responsibility among family members.

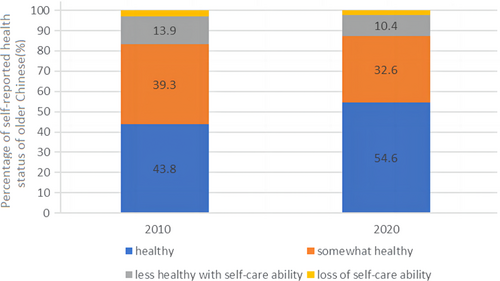

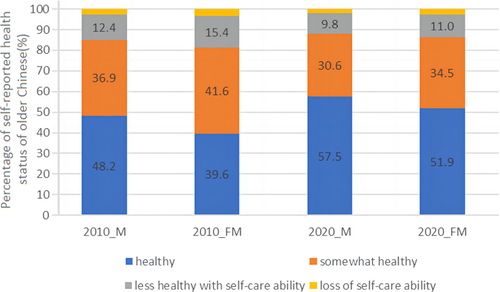

These micro-level findings provide a useful lens for understanding macro-trends unfolding in China. Despite concerns about health challenges associated with population aging, China's population census data clearly show improved health among its senior citizens. The 2010 and 2020 population census classify self-reported health status into four categories: healthy, somewhat healthy, less healthy with self-care ability, and loss of self-care ability. As Figure 3 shows, over 80% of older adults (aged 60 and above) were positive—either healthy or somewhat healthy—about their health. Notably, self-rated health has improved in the past decade. Those who reported “healthy” increased from 43.8% in 2010 to 54.6% in 2020, while those who were “less healthy with self-care ability” or “loss of self-care ability” decreased. Moreover, self-rated health has improved faster for women, resulting in growing gender parity in health. As Figure 4 shows, the gender difference in “healthy” status narrowed from 8.6 percentage points in 2010 to 5.6 percentage points in 2020. Men without self-care ability fell from 2.5% to 2.1%, compared to a decrease from 3.4% to 2.5% for women. Arguably a wide array of factors at the individual, household, community, and societal level accounts for this improvement. Among them is the ability of Chinese families to rearrange intergenerational support in coping with whatever challenges posed by falling fertility, shrinking family size, and declining multigenerational living.

While contributing to a deeper understanding of family dynamics in China in the past decade, the current literature has two notable limitations. First, its analysis of the health effect of different forms of living arrangement and intergenerational support is partial and incomplete. As the current research focus is tilted toward subjective measures of health and wellbeing such as life satisfaction and happiness, there is a need for equal attention to other aspects, including cognitive health, physical functioning, chronic or major illness, and social engagement. Second, when examining the impacts of living arrangement and intergenerational support on older adults' health and wellbeing, the current literature largely focuses on intra-family factors such as resources, preferences and care needs. As the subsequent section illustrates, with the introduction of universal pension and healthcare programs in the past decade, it is increasingly less tenable to ignore the impact of government policies and programs on family-level decisions and behaviors.

4 BRINGING GOVERNMENT SUPPORT BACK IN

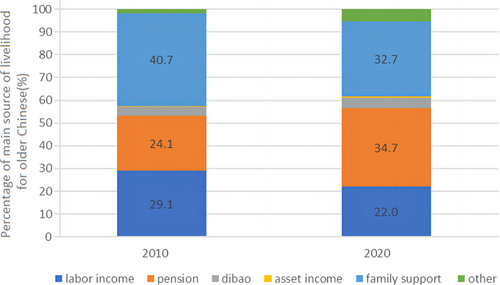

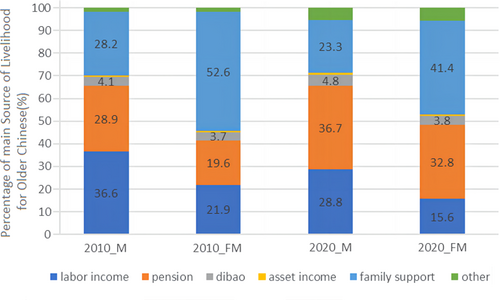

China's population census data have captured well the effect of government policy interventions, particularly the extension of pension coverage, on the livelihood of older Chinese in the past decade. The 2010 and 2020 population census listed seven mutually exclusive categories to measure the main source of livelihood for those aged 60 and above: labor income, pension, unemployment insurance, dibao (minimum livelihood guarantee program), income from assets, family support, and others. As Figure 5 shows, labor income, pension, and family support stood out as the dominant sources of livelihood. Nearly 94% in 2010 and 90% in 2020 chose one of them as their main source. By comparison, dibao—China's pivot social assistance program—was the main source for 3.9% of older Chinese in 2010 and 4.3% in 2020.

A notable change in the past decade was the growing importance of pension in supporting the livelihood of Chinese older adults. In 2010, pension was the main source of livelihood for 24.1% of the older population, falling behind family support and labor income; in 2020, it came out top with a 34.7% share. This change owes a great deal to China's remarkable pension coverage extension in the past decade: the roll-out of a pension scheme for rural population in 2009, followed by a similar scheme introduced in 2011 for urban nonworking residents and working individuals not covered by the urban employee pension scheme. Evidently, gender differences have become smaller in the past decade, with women experiencing a faster rise in pension and a more rapid decrease in reliance on family support as the main source of livelihood (see Figure 6). Pension coverage extension has also benefitted men, as their reliance on labor income decreased faster than that of women. In sum, government support through pension and other programs has become a significant source of livelihood for Chinese older adults.

While the current literature on living arrangements and intergenerational support has largely ignored the factor of government support, a separate and new line of research has started to examine how government policies and reforms reconfigure elderly care and affect older people's wellbeing. Using the 2010 and 2015 waves of CGSS data, Zhao et al. [23] report that Chinese attitudes towards elderly care responsibilities have been shifting. Belief in the traditional view that children should be the main elderly care providers is weakening, while a growing proportion of people expect the government to play a larger role and share the responsibility with children and the elderly themselves.

Han et al. [32] analyze the impacts of pension on the happiness level of Chinese older adults. Results from the 2014 wave of CFPS data show that receiving pension benefits is associated with a higher happiness level. Not surprisingly, those receiving more generous benefits from the urban employee scheme are happier than those enrolled in the urban and rural resident scheme. In another study, Hu and Wang [36] present further evidence that receiving benefits from the most privileged pension scheme for government and public institutions is associated with a higher level of life satisfaction than the two other less privileged schemes. Zhu and Walker [35] examine how receiving pension affects older people's social inclusion measured by family interaction, social support, social participation, and self-assessment. They find that having access to pension considerably improves older people's relationship with family members and friends, suggesting that the sense of security provided by pension promotes social inclusion, a precursor to or a component of health and wellbeing. Their analysis also shows that China's differentiated pension system privileges those with high pensions, who are found to have a higher level of social inclusion. These studies provide a nuanced portrait of China's pension reform. On the one hand, it has an equalizing effect by extending pension coverage to previously excluded groups, mainly rural residents and urban nonworking population. Pension coverage extension enhances their happiness level by providing a greater sense of financial security. On the other hand, the differentiated pension system itself has become a source of social variations. Through social comparison, those in the less privileged pension scheme have a lower level of subjective wellbeing. Further reform is therefore needed to reduce inequalities in pension benefits between different schemes.

Yip et al. [1] evaluate China's healthcare reform from 2009 to 2019. Using CHARLS data, they report substantial progress China has made in enhancing financial protection and improving equal access to healthcare. Notably, people of lower socioeconomic status, who are more resource constrained and vulnerable to health-related risks, have benefitted considerably from improved financial protection. Nonetheless, their evaluation also identifies remaining gaps in quality of care, efficiency in delivery, and public satisfaction. Other scholars have begun to assess the ongoing pilot on long-term care insurance. Feng et al. [42] show that the implementation of long-term care insurance has been cost-effective, reducing the length of hospital stay and inpatient expenditure. Using a difference-in-differences approach, Lei et al. [33] find that the introduction of long-term care insurance has produced a range of tangible benefits for both older people and their caregivers: lower likelihood of reporting unmet care needs, reduction in the intensity of informal care, savings in ADL-related expenditure and out-of-pocket health expenditure, improvement in self-reported health, and a lower mortality risk. Future research is needed to test whether the encouraging results can be replicated when the pilot is scaled up to more cities and provinces.

Few studies have explored the impacts of healthcare and pension reforms on living arrangement and family-based care and support. More research is needed in this regard. Currently, the growing body of research on living arrangements and intergenerational support remains largely separated from another line of research on the effectiveness of government policy interventions. Integrating these two lines of research would generate more and better insights about China's experience in tackling social challenges of population aging.

Based on a synthesis of main findings from the above two lines of research, this review article highlights government–society cooperation as a workable strategy that has helped China deal relatively well with social challenges of population aging in the past decade. The societal effort is reflected at the family level. The value of filial piety remains resilient, making it possible for families to re-negotiate living arrangement and intergenerational support in response to changes in family size and structure, preferences, and care needs. Equally important, family is no longer a “lone fighter” in coping with demographic and livelihood challenges. Through pension and healthcare reforms and by developing social services and amenities, the government has stepped in to share elderly care responsibilities, with benefits reaching people of lower socioeconomic status. China's experience in the 2010s offers a useful lesson for tackling population aging in the future.

5 DISCUSSION

China's rapid population aging and remarkable family-level changes have raised concerns about family-based elderly care and the wellbeing of older adults. Despite the widespread concerns, the 2020 population census data clearly show improved livelihoods and health among the Chinese aged 60 and above in the past decade.

Drawing on two separate lines of research, this review article suggests that a key lesson from China lies in the government–society cooperation. According to the literature on living arrangement and intergenerational support, while some traditional values and norms have been fading away, filial piety remains relatively strong in China. It enables family members to adapt to new changes, prompting children living afar or close, migrant or nonmigrant, to re-negotiate financial, instrumental, and emotional support to their parents in practical ways. Another expression of family solidarity is grandchild care-giving, which provides a sense of purpose and self-fulfillment and produces health-enhancing effects for grandparents either in multigeneration or skipped-generation households.

The literature on government policies and programs provides a complementary yet equally important account. By extending the pension and medical insurance coverage to previously excluded groups, the government has stepped in to support individuals and families. Improved financial protection has a pronounced effect on the wellbeing of elderly people from low-income groups and economically disadvantaged areas. Without government support, millions of families may find themselves in a more strained situation. Having the family and government share elderly care responsibilities also meets the growing expectations of the public.

While affirming the importance of government support, the current literature also recognizes the need for further reform to enhance the government–society cooperation. Several challenges are yet to be tackled. For one, China's pension system is differentiated, with varying levels of pension benefits for different groups. This variation in benefits can pose challenges for further enhancing the welfare of groups with lower benefits. [32, 35, 36]. A similar problem exists in the healthcare system. Making the pension and healthcare systems more equitable will improve financial protection for vulnerable people, address their resource constraints, and enhance their wellbeing, thereby contributing to China's active and healthy aging agenda. For another, discrepancies between preferred and actual living arrangement/care provision remain a problem for a sizable portion of older Chinese [39]. As many families are constrained, financially or otherwise, to realize their preferred living arrangement and care-giving, targeted support from the government is necessary. In short, how the government–society cooperation plays out in the next decade and beyond will have profound implications for the living arrangement, intergenerational support and well-being of older adults in China.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Litao Zhao: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); validation (lead); visualization (lead); writing—original draft (lead); writing—review & editing (lead).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Professor Wong Tien Yin for the invitation to write this review. The author has no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study uses publicly available data published by China's National Bureau of Statistics, which complies with ethics standards.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the website of National Bureau Statistics of China at http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/indexch.htm and http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm.

REFERENCES

- 1 China maintained a low total fertility rate (TFR) between 2010 and 2020 at the level of 1.2–1.3. Total migrant population increased nearly 70% from 221 million in 2010 to 376 million in 2020. See China Population Census Yearbook 2020.

- 2 In terms of rural–urban difference in family structure, urban areas had a considerably higher percentage of one-generation households in 2000 and 2010, while rural areas had a considerably higher percentage of three-generation households. In 2020, rural and urban families were much alike. The share of one-generation households was only slightly higher in urban areas than in rural areas (52.5% vs. 48.6%).