Subject-specific segregation of functional territories based on deep phenotyping

[Corrections added in affiliation of Lucie Hertz-Pannier on 07th January, 2021]

Funding information: Human Brain Project SGA3, Grant/Award Number: 945539; Human Brain Project SGA2, Grant/Award Number: 785907

Abstract

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has opened the possibility to investigate how brain activity is modulated by behavior. Most studies so far are bound to one single task, in which functional responses to a handful of contrasts are analyzed and reported as a group average brain map. Contrariwise, recent data-collection efforts have started to target a systematic spatial representation of multiple mental functions. In this paper, we leverage the Individual Brain Charting (IBC) dataset—a high-resolution task-fMRI dataset acquired in a fixed environment—in order to study the feasibility of individual mapping. First, we verify that the IBC brain maps reproduce those obtained from previous, large-scale datasets using the same tasks. Second, we confirm that the elementary spatial components, inferred across all tasks, are consistently mapped within and, to a lesser extent, across participants. Third, we demonstrate the relevance of the topographic information of the individual contrast maps, showing that contrasts from one task can be predicted by contrasts from other tasks. At last, we showcase the benefit of contrast accumulation for the fine functional characterization of brain regions within a prespecified network. To this end, we analyze the cognitive profile of functional territories pertaining to the language network and prove that these profiles generalize across participants.

1 INTRODUCTION

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a noninvasive neuroimaging technique widely used to study the neural correlates of mental processes in the human brain. As such, it provides a means to characterize functional responses of brain regions. Yet, to date, fMRI research in cognitive neuroscience has focused mostly on group-level effects in the performance of isolated tasks.1 On the other hand, the extraction of elementary cognitive components—from neuroimaging data in general—further requires the establishment of a link between tasks and cognitive functions (Poldrack & Yarkoni, 2016; Posner, Petersen, Fox, & Raichle, 1988; Varoquaux et al., 2018). This can only be achieved by combining responses to many tasks, which hinges on pooling data or results from different studies. So far, data pooling relies on either meta-analytic or mega-analytic methods applied to fMRI data, allowing knowledge on brain systems to be accumulated across studies. However, as it is directly impacted by intersubject and intersite variability, this approach hinders the fine demarcation of brain regions. Contrariwise, individual mapping is free from this variability (Hanke et al., 2014; Huth, de Heer, Griffiths, Theunissen, & Gallant, 2016), but the resulting functional topographies have not yet been integrated into brain function templates.

We thus investigate herein the feasibility of performing individual functional atlasing free from intersubject and intersite variability, as an effort to establish an univocal relationship between functional segregation of brain regions and human cognition. To this end, we leverage a collection of task-fMRI brain images from the individual brain charting (IBC) dataset, acquired at high spatial resolution—that is, 1.5 mm—in a fixed cohort and environment. We make use of the first IBC-dataset release (Pinho et al., 2018) composed by 12 tasks that cover already a wide variety of cognitive systems. We describe an individual-brain-modeling approach that benefits from high-resolution data, to better account for subject-specific functional organization. The main goal of this analytic approach is to reliably localize and extract regional-specific signatures from the tasks probed, at a fine-grained scale, and delineate neural territories based on such functional fingerprints.

To understand the expected benefits of this approach, we first review the current practices for data integration and knowledge accumulation in cognitive neuroscience. Particularly, knowledge accumulation in the field relies not only on task-specific studies but also, and increasingly, on meta-analyses and mega-analyses as well as individual brain mapping.

Task-specific group studies probe the neural correlates underlying the performance of a few experimental conditions. Effects-of-interest are then obtained from linear combinations—also known as contrasts—of these conditions. Ideally, activation patterns elicited by the contrasts should provide a mapping of the targeted mental process. Nevertheless, effects-of-interest may incorporate an undetermined level of inaccuracy, since contrasts are typically bound to idiosyncrasies of the task implementation. Some specific issues can be outlined: (a) arbitrary features of the elements composing the stimuli; (b) cues provided during performance and/or introduced informally by the experimenter during training, that can induce different cognitive strategies (Kirchhoff & Buckner, 2006; Miller, Donovan, Bennett, Aminoff, & Mayer, 2012); (c) specifications of the experimental equipment interacting with the presentation of the stimuli; and (d) temporal structure of the task, that influences perception and reaction times. These constraints may hamper the identification of brain cognitive systems from functional signatures.

Meta-analysis is a way to generalize across different implementations of tasks (Costafreda, 2011; Gurevitch, Koricheva, Nakagawa, & Stewart, 2018; Müller et al., 2018; Wager, Lindquist, & Kaplan, 2007). This approach typically relies on pooling published results from different task-specific studies, to assess which functional regions are consistently linked to some mental functions. However, combining results from different studies is subject to loss of information due to sparse peak-coordinate representation and the difficulty of consistently annotating cognitive activity. The variability in spatial location of activation across studies is caused mostly by the impact of: (a) the diversity of experimental settings involved in data collection; (b) the use of different data processing routines (Carp, 2012); and (c) between-subject variability, especially in the small sample-size regime encountered in the majority of neuroimaging studies (Button et al., 2013).

As an alternative to meta-analysis, mega-analysis relies instead on pooled analysis of brain maps (Costafreda, 2009, 2011). This approach solves the problems linked to the usage of postprocessed data taken from different sources. Recent studies, both in cognitive mapping (Schwartz et al., 2012; Schwartz, Thirion, & Varoquaux, 2013; Varoquaux et al., 2018; Varoquaux, Schwartz, Pinel, & Thirion, 2013) and in physiological phenotyping (Wager et al., 2013), have used mega-analytic methods in order to examine large-scale neuroimaging data. As other approaches, mega-analyses also suffer from the lack of nomenclature in the annotations of task-related data (Poldrack & Yarkoni, 2016). In this respect, large-scale public repositories of task-fMRI data, namely OpenNeuro (Poldrack et al., 2013) and NeuroVault (Gorgolewski et al., 2015; Gorgolewski, Varoquaux, et al., 2016) are opening novel perspectives regarding system-level cognitive studies. Nevertheless, it is still a challenge to mitigate heterogeneity in the data related to: (a) different acquisition settings; and (b) functional and anatomical intersubject variability.

Recent neuroimaging studies have started to adopt individual analysis, in order to overcome both functional and anatomical intersubject variability (Braga & Buckner, 2017; Chang et al., 2019; Fedorenko, Behr, & Kanwishera, 2011; Frost & Goebel, 2012; Gordon et al., 2017; Hanke et al., 2014; Haxby et al., 2011; Huth, Lee, et al., 2016; Huth, de Heer, et al., 2016; Laumann et al., 2015; Nieto-Castanon & Fedorenko, 2012). Specifically, previous neuroimaging-data initiatives have already triggered the development of large-scale datasets, laying the groundwork for a more comprehensive and systematic analysis of the organization of neural structures. Many of these projects consist of resting-state fMRI data (Biswal et al., 2010; Jovicich et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2017; van Essen et al., 2017) and some of them are specifically dedicated to research on clinical neuroscience (Book, Stevens, Assaf, Glahn, & Pearlson, 2016; Jack et al., 2015). Yet, resting-state fMRI analyses, while providing fine delineations of brain structures, do not clarify the organization of cognitive functions across territories. The task-fMRI tenet of the Human Connectome Project (HCP) sought to delineate and characterize representative functional territories, according to their implication in task performance (Barch et al., 2013; Glasser et al., 2016). The battery of tasks developed for the study comprises only 7 tasks defining maps of 20 main contrasts2—arguably not enough for a comprehensive cognitive mapping. Much emphasis of the project was also given to characterizing population variability, in order to both conceive a common contrast atlas of the cohort (Glasser et al., 2016) and investigate correlations with behavior (Smith et al., 2015) or genetics (Kochunov et al., 2015). As a precursor of the IBC dataset, Pinel et al. (2007) reported a standardized large-scale acquisition set (81 participants) of a fast event-related task—ARCHI Standard—that is also included in the IBC set of experiments. However, this study was dedicated to between-subject comparison rather than fine cognitive mapping. Part of the data are openly available in the Brainomics/Localizer database (Orfanos et al., 2017). This large-scale acquisition has now been extended to four localizers, all of which are used in the IBC dataset (i.e., ARCHI Standard, ARCHI Spatial, ARCHI Social, and ARCHI Emotional), and individual functional data, from 78 participants, make up the “CONNECT/Archi” Database (Pinel et al., 2019). Yet, this dataset only accounts for four different tasks, comprising 23 main-contrast maps. Worthy of note is also the studyforrest initiative. It stands for a group of openly available multimodal datasets stored in the OpenNeuro repository, featuring fMRI data on the continuous presentation of scenes included in the “Forrest Gump” movie. This project has thus launched several studies dedicated to investigating the neurocognitive encoding of complex auditory and visual information, like the ability to perceive language, music or social interplay, by modeling specific audio and visual properties of the stimuli (Hanke et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Sengupta et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the tasks employed across these studies were restricted to naturalistic stimuli. Hence, the ensuing results cannot be easily integrated into current brain-function knowledge bases.

The IBC dataset yields a comprehensive collection of individual contrasts that aims at characterizing the cognitive components underlying the tasks. The first release of this dataset (Pinho et al., 2018) pertains mostly to data acquired from localizers, using a fast and randomized design, whose conditions range from perception to higher-order thinking skills (Barch et al., 2013; Pinel et al., 2007). Besides, data from a rapid-serial-visual-presentation (RSVP) paradigm on language comprehension were also included in this first release (Humphries, Binder, Medler, & Liebenthal, 2006; Pinho et al., 2018). Given that language constitutes a primary form of social behavior among humans and its manipulation relies on higher-order cognitive processes, the corresponding functional networks share neural substrates with other cognitive-control mechanisms (Fedorenko, 2014). Plus, an individualized data integration approach is herein developed, keeping in mind that an average brain may not be similar to an individual brain (Fedorenko et al., 2011; Fedorenko, Duncan, & Kanwisher, 2012).

In this article, we provide a series of results that validate functional atlasing on the basis of individual contrast maps. With respect to previous work, we focus on quantitative arguments to precisely assess the amount of information captured by individual atlasing as well as the predictive value of the individualized model. To this end, we make use of the 51 main-contrast maps that can be extracted from the 12 tasks featuring the first release of the IBC dataset. These contrast maps are linearly independent and each contrast map refers to two contrasts, that is, to the labeling contrast and its reverse. Concretely, these contrast maps pertain to unthresholded z-maps that are available in NeuroVault, collection #4438 (https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:4438).

First, we performed a quality check of the IBC data to verify the reliability of the functional signatures measured in the contrast maps. We thus assessed whether contrast maps of those tasks taken from previous studies were successfully reproduced. Second, we extended this quality-checking investigation and studied the amount of variability across runs (with different phase-encoding directions) and across participants in these contrast maps. Third, we synthesized the individual contrast maps into latent components, that reflect subject-specific representations, using dictionary learning; to describe the cognitive counterpart of these components, each of them was labeled according to the most contributive contrast. Similarly to the evaluation performed for the contrast maps, we also investigated the intrasubject and intersubject stability of these individual components. Fourth, to quantify the contribution of each task to these common representations, we tested whether shared variability between contrast maps can be learnt, by estimating the prediction accuracy of contrasts belonging to one task from contrasts belonging to all remaining tasks. Importantly, we also investigated how much our predictions were affected by subject-specific organization. Fifth, we demonstrate how cognitive mapping can benefit from contrasts accumulation, by analyzing functional fingerprints of regions within the language network. We thus selected and individualized six regions-of-interest from this network and draw their cognitive profile according to a subset of language-related contrast maps from different tasks, in order to disambiguate their functional role.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

To prevent any ambiguity on the interpretation of MRI-related terms, definitions follow the Brain-Imaging-Data-Structure (BIDS) Specification version 1.2.1 (Gorgolewski, Auer, et al., 2016).

2.1 Participants

The IBC dataset refers to neuroimaging data collected in 13 individuals3 (11 males, 2 females; age mean/SD = 34 ± 5 years) with no previous history of psychiatric, neurological or any other medical disorders that can change brain function. Handedness was determined with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971); results of the survey indicate that members of the cohort are predominantly right handed (range: [0.3, 1]; mean ~0.8).

The experiments were carried out with the understanding and formal consent of the participants, in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and the French public health regulation.

For more information about demographic data of the cohort, consult Table A1 of Appendix A.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Stimuli

Stimuli consisted of both visual and auditory material presented to the participant during blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) runs. For all tasks, they were delivered through custom-made scripts that allowed for a fully automated environment and computer-controlled collection of the behavioral data. Both visual and auditory stimuli of the protocols obtained from the HCP consortium (Barch et al., 2013) were translated to French.

All protocols are available in a public repository: https://github.com/hbp-brain-charting/public_protocols.

2.2.2 MRI equipment

The fMRI data were acquired using an MRI scanner Siemens 3T Magnetom Prismafit and a Siemens Head/Neck 64-channel coil.

Behavioral responses of the participants were registered during the MRI sessions with one of the two MR-compatible, optic-fiber response devices, depending on the protocol: (a) a five-button ergonomic pad (Current Designs, Package 932 with Pyka HHSC-1x5-N4); and (b) a pair of in-house custom-made sticks featuring one-top button. MR-Confon package was used as audio system in the MRI environment.

All sessions were conducted at the NeuroSpin platform of the CEA Research Institute, Saclay, France.

2.3 Experimental procedure

The task-fMRI data of the IBC-dataset first release were collected per participant in four different MRI sessions. Upon arrival to the research center, participants were instructed about the execution and timing of the tasks referring to the upcoming session. Every session was always composed of several runs dedicated to one or more tasks and each task-related run was always repeated in multiples of two, alternating its phase-encoding direction (see Section 2.5 for details).

Full information on the structure of the MRI sessions, namely which tasks were acquired in every session, can be found in Sections 2.3 and 2.5 and Tables 2 and 3 of Pinho et al. (2018) as well as in Section 2 of the IBC documentation (see Section 2.6 of this article for more details about the IBC documentation).

Additionally, a detailed description about the procedures that were undertaken toward handling and training the participant before each MRI session are also provided in Section 2.3 of Pinho et al. (2018).

2.4 Experimental paradigms

The first release of the IBC dataset comprises 12 tasks. Their majority pertains to already-existing paradigms developed and validated in previous studies. They were thus combined in four different MRI sessions according to this criterion. For further details about the organization of the MRI sessions, consult Table 2 of Pinho et al. (2018). Concretely, these 12 tasks refer to the reproduction of the ARCHI and HCP batteries, with minor adaptations, as well as to a new task addressing language comprehension and based on a RSVP paradigm. A summary of the experimental paradigm of each task is given next. Each design is categorical, that is, it relies on the principle of “cognitive subtraction” as means to isolate effects-of-interest across experimental conditions within every task. All conditions per task are listed and described in Appendix B. More information about adaptation and implementation of the corresponding software protocols can be found in Section 2.4 of Pinho et al. (2018).

2.4.1 ARCHI tasks

The ARCHI battery was developed at NeuroSpin Research Center and validated in the context of numerous neuroimaging projects, namely Pinel et al. (2007, 2019). It is composed of four localizers—ARCHI Standard, ARCHI Spatial, ARCHI Social and ARCHI Emotional—addressing different psychological domains. For further details about these localizers, consult Appendix B.1; the list of experimental conditions composing each localizer, together with their descriptions, can be found in Tables A2–A5, respectively.

2.4.2 HCP tasks

The HCP battery refer to a subset of tasks—HCP Emotion, HCP Gambling, HCP Motor, HCP Language, HCP Relational, HCP Social, and HCP Working Memory—that were originally developed in the task-fMRI tenet of HCP, as described in Barch et al. (2013). They are organized in block-design paradigms, covering a variety of motor, sensory, emotional, and high-order cognitive mechanisms. For further details about the HCP tasks, consult Appendix B.2; the list of experimental conditions composing each task, together with their descriptions, can be found in Tables A6–A12, respectively.

2.4.3 RSVP Language task

Finally, the RSVP Language task consists in the RSVP of linguistic constituents, such as sentences of different complexity, jabberwocky, words, pseudowords, and nonwords. This novel task is a follow-up of the one presented in Humphries et al. (2006) and it aims foremost at dissociating syntactic and semantic processes related to language comprehension. Main conditions of this task are listed and described in Table A13 in Appendix B.2.8.

2.5 Imaging-data acquisition

FMRI data were collected using a gradient-echo (GE) pulse, whole-brain multiband (MB) accelerated (Feinberg et al., 2010; Moeller et al., 2010) echo-planar imaging (EPI) T2*-weighted sequence with BOLD contrasts, using the following parameters: the repetition time (TR) is 2,000 ms; the echo time (TE) is 27 ms; the flip angle is 74°; the field-of-view (FOV) is 192 × 192 × 140 mm3; voxel size is 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3; the slice orientation is axial; slices are acquired in interleaved fashion; in-plane acquisitions were accelerated by a factor (GRAPPA) of 2; and across slices, an MB factor of 3 was used. Two different acquisitions for the same task were always performed using two opposite phase-encoding directions: one from posterior to anterior (PA) and the other from anterior to posterior (AP). The main purpose was to mitigate geometrical distortions while assuring built-in, within-subject replication of the same tasks.

Spin-echo (SE) EPI-2D image volumes were acquired in order to correct for spatial distortions, using the following parameters: a TR of 7,680 ms; a TE of 46 ms; an FOV of 192 × 192 × 140 mm3; a voxel size of 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3; axial slice orientation; and acceleration factor (GRAPPA) = 2. Similarly to the GE-EPI sequences, two different acquisitions were also performed using PA and AP phase-encoding directions.

In addition, a 3D magnetization-prepared rapid GE (MPRAGE) T1-weighted anatomical-image volume, covering the whole brain, was acquired with the following parameters: voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3; sagittal slice orientation; flip angle of 9°; and FOV of 256 × 256 × 160 mm.

2.6 Data storage

The online access of all data is assured by the Human Brain Project (HBP) EBRAINS platform as well as the OpenNeuro public repository (Poldrack et al., 2013) under the accession number ds000244 (dataset DOI: 10.18112/openneuro.ds000244.v1.0.0).

The individual and unthresholded z-maps, obtained from all contrast maps of the aforementioned experimental conditions (see Section 2.4 and Appendix B), can be found in the NeuroVault repository (Gorgolewski et al., 2015), under the collection with the id = 4438: https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:4438.

The scripts used for data analysis are publicly available under the Simplified BSD license: https://github.com/hbp-brain-charting/public_analysis_code.

The documentation of the dataset, containing a full description of the experimental designs, acquisition parameters and analysis pipeline, is accessible on the IBC website: https://project.inria.fr/IBC/data/.

For further details, consult the Data and Code Availability Statement provided as Supplementary Material.

2.7 Data analysis

2.7.1 Preprocessing

Raw data were preprocessed using PyPreprocess (https://github.com/neurospin/pypreprocess). This framework stands for a collection of Python scripts oriented toward a common workflow of fMRI-data preprocessing analysis. It is built upon the Nipype interface (Gorgolewski et al., 2011) v0.12.1, thus allowing for the stand-alone use of precompiled modules in SPM12 software package (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK) v6685, and FSL library (Analysis Group, FMRIB, Oxford, UK) v5.0, used for the preprocessing of neuroimaging data.

All fMRI images, that is, GE-EPI volumes, were collected twice with reversed phase-encoding directions, resulting in pairs of images with distortions going in opposite directions. Susceptibility-induced off-resonance field was estimated from the two SE EPI volumes in reversed phase-encoding directions. The images were corrected based on the estimated deformation model. Details about the method and its implementation in FSL can be found in Andersson, Skare, and Ashburner (2003) and Smith et al. (2004), respectively.

Further, the GE-EPI volumes were aligned to each other within every participant. A rigid body transformation was employed, in which the average volume of all images was used as reference (Friston, Frith, Frackowiak, & Turner, 1995).

All analysis was carried out in both volume and cortical surface. For the volume-based analysis, the corresponding T1-weighted MPRAGE (anatomical) volume was co-registered onto the mean EPI volume for every participant (Ashburner & Friston, 1997). All anatomical volumes were then segmented to finally allow for the normalization of both functional and anatomical data (Ashburner & Friston, 2005). Concretely, the segmented volumes were used to compute the deformation field for normalization into the MNI152 space. The deformation field was then applied to the EPI data. In the end, all volumes were resampled to their original resolution, that is, 1 mm isotropic for the MPRAGE T1-weighted anatomical images and 1.5 mm for the EPI images. For the cortical-surface analysis, the anatomical and motion-corrected fMRI images were given as input to FreeSurfer v6.0.0, in order to extract meshes of the tissue interfaces and a sampling of functional activation on these meshes, as described in van Essen, Glasser, Dierker, Harwell, & Coalson, 2012. The corresponding maps were then resampled to the fsaverage7 template of FreeSurfer (Fischl, Sereno, Tootell, & Dale, 1999).

2.7.2 fMRI-model specification

fMRI data were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM). Regressors of the model were designed to capture variations in BOLD response strictly following stimulus timing specifications. They were estimated through the convolution of boxcar functions, that represent per-condition stimulus occurrences, with the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF), defined according to Friston, Fletcher, et al. (1998) and Friston, Josephs, Rees, and Turner (1998).

To build such models, paradigm descriptors grouped in triplets (i.e., onset time, duration and trial type) according to BIDS Specification were determined from the log files' registries generated by the stimulus-delivery software.

To account for small fluctuations in the latency of the HRF peak response, additional regressors were computed based on the convolution of the same task-conditions profile with the time derivative of the HRF.

Nuisance regressors were also added to the design matrix in order to minimize the final residual error. To remove signal variance associated with spurious effects arising from movements, six temporal regressors were defined for the motion parameters. Further, the first five principal components of the signal, extracted from voxels showing the 5% highest variance, were also regressed to capture physiological noise (Behzadi, Restom, Liau, & Liu, 2007).

In addition, a discrete-cosine basis was included for high-pass filtering (cutoff =  ). Model specification was implemented using Nistats library v0.0.1b, a Python module devoted to statistical analysis of fMRI data (http://nistats.github.io), that leverages Nilearn (Abraham et al., 2014), a Python library for statistical learning on neuroimaging data (https://nilearn.github.io).

). Model specification was implemented using Nistats library v0.0.1b, a Python module devoted to statistical analysis of fMRI data (http://nistats.github.io), that leverages Nilearn (Abraham et al., 2014), a Python library for statistical learning on neuroimaging data (https://nilearn.github.io).

2.7.3 Model estimation

To restrict GLM-parameters estimation of volume data to gray-matter voxels, a group-level gray-matter mask was initially generated by averaging all individual, gray-matter “density” maps obtained upon the preprocessing step; it was then thresholded at a liberal level, that is, 0.25, which corresponds to an average probability of 25% of finding gray matter in a certain voxel across subjects, in order to obtain a comprehensive mask. An illustration of the group-level, gray-matter mask is provided as Supplementary Material.

Regarding noise modeling, a first-order autoregressive model was used in the maximum likelihood estimation procedure.

A mass-univariate GLM fit was applied separately to the preprocessed GE-EPI data of each run with respect to a specific task. Parameter estimates pertaining to the experimental conditions were thus computed, along with the respective covariance at every voxel. Various contrasts—linear combinations of the effects—were then defined, referring only to differences in evoked responses between either (a) two conditions-of-interest or (b) one condition-of-interest and baseline. GLM estimation and subsequent statistical analyses were also implemented using Nistats v0.0.1b. FMR-data analysis was first employed with no regularization and, afterward, with a smoothing parameter set to 5 mm full-width-at-half-maximum. Such procedure allows for an increase of the functional signal-to-noise ratio (fSNR) and it facilitates between-subject comparison. The images used in Section 3 are based on smoothed data. The same analytical steps were carried out on the data sampled on the cortical surface.

2.7.4 Summary statistics

Because data from each task were collected, at least in two acquisitions, with opposite phase-encoding directions (see Section 2.5 for details), statistics of their joint effects were calculated for each subject with a fixed-effects (FFX) model. Specifically, t-statistics were computed at every voxel for every contrast map.

After completing the within-subject level analysis, a group-conjunction analysis (Heller, Golland, Malach, & Benjamini, 2007) was performed on the main contrasts; significance was assessed against the null hypothesis asserting that less than a fourth of the subjects display activity in a given voxel. The motivation to employ conjunction analysis instead of the random-effects (RFX) linear model relates to the small size of the cohort, that is, 13 subjects. Due to this small size, the variance term of the RFX model is estimated with few degrees of freedom, leading to unreliable and conservative estimates. Moreover, as variability tends to co-localize with large effects (Thirion et al., 2007), a form of inference relying on the consensus between subjects is more appropriate for small samples. Map consistency using either conjunction analysis or RFX-model approach was investigated on postprocessed data, with and without smoothing. Concretely, the distributions of the Jaccard index between pairs of group-level z-maps from the original set and bootstrap resampling were estimated using either conjunction analysis or RFX-model, to assess how much they are impacted by sampling variability in the population. Results are provided as Supplementary Material. We observe that the median of the indices is higher for the conjunction analysis while its interquartile range is smaller, indicating that group-level conjunction contrasts are more consistent across different samples of the population. We also denote that there is a likely difference between RFX results obtained for smoothed and unsmoothed data, whereas there is no difference between the conjunction counterparts; this evidence also hints at a greater consistency of the second-level results obtained from conjunction, regardless different postprocessing choices.

A z-transform of the t-maps was always performed both on individual and group-level statistical maps. Such procedure allows for standardized results, which are not anymore dependent on the number of degrees of freedom. This is particularly useful when comparing results from different datasets (see Sections 2.7.5 and 3.1).

2.7.5 Assessing reproducibility and functional variability

In order to assess the reproducibility of the main results, group-level contrast z-maps of the IBC dataset were compared to the corresponding ones obtained from the original ARCHI dataset, n = 78 (Pinel et al., 2019) as well as to those obtained from a subset of the HCPS900 dataset, n = 786.

To evaluate how consistent the task-specific functional signatures are among participants, the correlation of the contrast maps was computed both between and within subjects, that is, both between all subjects' pairs of FFX individual maps and between pairs of “PA” and “AP” maps of the same task per subject. The mean and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were then estimated from the distribution of this measure, as a way to quantify the functional variability of the contrasts within and across individuals.

2.7.6 Dictionary learning

To obtain individual topographies that summarize the spatial representation of the effects-of-interest, dictionary learning was applied to statistical maps featuring the main contrasts of each experiment, in each subject. This sparse decomposition method extracts spatially distinct components from the joint distribution of contrast values. It thus provides a low-dimension representation of the overlapping neural support of the contrasts probed in the dataset.

We used a multiple-subject dictionary learning model that captures functional correspondence across datasets, as described in Varoquaux et al. (2013). Such hypothesis allows the factorization of the individual contrast maps into a dictionary of cognitive profiles (common to all subjects) plus subject-specific spatial maps (also known as loadings). The sparsity was enforced with an ℓ1−norm penalty on the loadings of the components, together with a nonnegative constraint.

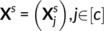

obtained for c = 51 contrasts in a subject s ∈ [n]. By enumerating the values across a mesh of vertices, each

obtained for c = 51 contrasts in a subject s ∈ [n]. By enumerating the values across a mesh of vertices, each  is a p−dimensional vector, where p is the number of vertices; Xs is thus a matrix of size p × c. Functional-correspondence dictionary learning solves the following minimization problem for λ > 0:

is a p−dimensional vector, where p is the number of vertices; Xs is thus a matrix of size p × c. Functional-correspondence dictionary learning solves the following minimization problem for λ > 0:

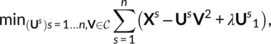

denotes the set of matrices with row norm smaller than 1. Us matrices have shape p × k, whereas the functional-loading matrix V has shape k × c, k being the number of components. Herein, we used k = 20. On the other hand, the V matrix defines the functional characteristics of the components. The estimated subject-specific spatial components (Us), s ∈ [n] can be interpreted as individual topographies; these components may overlap, although their values are zero in most regions. The λ parameter was calibrated in order to yield a sparsity of around 75%. As the estimation problem is nonconvex, initialization matters; here, we created an initial V matrix by clustering the voxels across subjects into k = 20 clusters and took the normalized average of the cluster signal. The implementation relies on the mini-batch k-means and the dictionary-learning methods of scikit-learn v0.21.3 (Pedregosa et al., 2011), a Python machine-learning library (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/).

denotes the set of matrices with row norm smaller than 1. Us matrices have shape p × k, whereas the functional-loading matrix V has shape k × c, k being the number of components. Herein, we used k = 20. On the other hand, the V matrix defines the functional characteristics of the components. The estimated subject-specific spatial components (Us), s ∈ [n] can be interpreted as individual topographies; these components may overlap, although their values are zero in most regions. The λ parameter was calibrated in order to yield a sparsity of around 75%. As the estimation problem is nonconvex, initialization matters; here, we created an initial V matrix by clustering the voxels across subjects into k = 20 clusters and took the normalized average of the cluster signal. The implementation relies on the mini-batch k-means and the dictionary-learning methods of scikit-learn v0.21.3 (Pedregosa et al., 2011), a Python machine-learning library (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/).

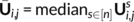

were obtained by first computing the median of the components, as follows:

were obtained by first computing the median of the components, as follows:

Then, the same labeling strategy, as the one described above, was employed at every vertex. Note that by construction, a label was assigned to a given vertex if, at least, half of the subjects obtained a nonzero loading for the corresponding component at that vertex. Because components were labeled to outline their functional definition, we chose the contrast label with the highest value in the dictionary—row of V matrix—for that component.

The stability of this decomposition was thus tested by reestimating the dictionary, using only AP- and PA-based activation maps; spatial correspondence of the components was measured through their intrasubject and intersubject correlations. A priori, it was hypothesized that such correlations would be higher within than between subjects.

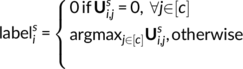

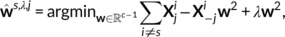

2.7.7 Prediction of contrast maps across tasks

Because functional activations are overlapping between the IBC tasks due to common underlying cognitive components, we hypothesized that such similarities allow for predicting these contrast maps from the contrast maps of other tasks.

of Xs, j ∈ [c]. We shall also consider the remaining columns

of Xs, j ∈ [c]. We shall also consider the remaining columns  that represent brain activity from the remaining contrasts, as well as all data from the other subjects Xi, i ≠ s. To this end, we used Ridge regression:

that represent brain activity from the remaining contrasts, as well as all data from the other subjects Xi, i ≠ s. To this end, we used Ridge regression:

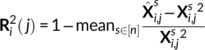

In practice, a leave-three-subjects-out cross-validation experiment was employed, that is, training sets were composed of the contrasts from 10 subjects and 3 were left for the test set. Contrasts from the same task were predicted jointly, as they are correlated; hence, predicting one from the other would lead to optimistic bias. Ward's clustering method was used for parceling the brain volume into 100 subregions. The aforementioned analysis was performed in these subregions, similarly to what was done in Tavor et al. (2016). Prediction accuracy at every voxel was measured in terms of R2−scores obtained from each data partition. The maximum of this statistic across tasks was reported afterward. The reason for taking the maximum relates to the fact that, at a given location, it is unlikely to obtain robust responses for more than one task; this means that the baseline of the predictive score is zero,4 as confirmed by the analogous computation performed with a dummy classifier. It thus becomes more appropriate to select the maximum rather than the average or the median of the accuracy predictions across tasks, since the maximum outlines the existence of, at least, one latent cognitive dimension explaining activity in a certain brain location.

Finally, the same experiment was repeated but scrambling the subject correspondence between train and test through a random permutation. This aims at quantifying the subject specificity of these functional relationships.

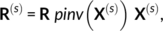

2.7.8 Region-of-interest analysis

The functional-response profiles of a set of six brain regions, previously reported to participate in the language network, were obtained from a subset of contrasts pertaining to language processing. Six regions-of-interest, based on the statistical maps obtained from Pallier, Devauchelle, and Dehaene (2011), were selected a priori.

Afterward, for each region-of-interest, the mean of the z-scores at the voxels of the selected contrasts, belonging to the corresponding subject-specific region mask, was computed in every subject. Then, for each contrast, the average across subjects and its 95% CI was estimated in order to create the functional fingerprint specific of that region.

Moreover, a leave-one-group-out cross-validation experiment was set in order to verify whether voxels can be correctly assigned to one of these six regions-of-interest, according to the profile of their functional activations. This experiment was run on data from all participants; voxels belonging to pairs of regions-of-interest were classified to their respective region—based on the functional contrasts—using a linear support vector classifier. Training sets were composed of data from 12 participants and prediction was performed in the data from the remaining participant; each group was thus referring to the data from one participant. Predictions were made between all possible combinations of two regions from the original collection of six regions-of-interest. Accuracy prediction at every voxel was measured in terms of classification accuracy per region pair. This analysis was performed using scikit-learn. To compute the chance level, the same procedure was employed using the scikit-learn's dummy classifier.

3 RESULTS

All results herein described were obtained from the individual and unthresholded z-maps of the main contrasts extracted from each task. For a cognitive description of the effects-of-interest depicted by these contrasts, refer to the IBC documentation available on the website of the project (https://project.inria.fr/IBC/data/).

3.1 Reproduction of ARCHI and HCP tasks

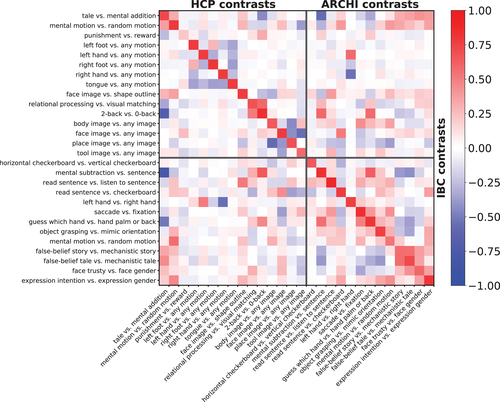

Figure 1 displays the correlation of group-average z-maps between corresponding contrasts obtained from: (a) IBC versus ARCHI datasets and (b) IBC versus HCP datasets. The diagonal of the matrix refers to homologous contrasts and, therefore, it shows how successfully the maps of ARCHI and HCP were reproduced in IBC. The high correlations present on the diagonal confirm that the functional signatures of the same contrast maps were preserved across different datasets, providing clear evidence that the original results obtained in these large datasets are reproduced using the IBC dataset. One exception stands for the punishment-reward contrast map of the HCP Gambling task; nonetheless, results for this contrast map were also very variable within and between subjects for the original dataset (see Figure A1 in Appendix C). Additionally, correlations between different contrast maps provide a quantitative measure of the similarity of their neural correlates. For instance, left hand versus right hand contrast map from the ARCHI Standard task and left hand versus any motion contrast map from the HCP Motor task are highly correlated because both functional signatures mostly refer to movements of the left hand. As another example, social-interaction motion versus random motion contrast maps from both ARCHI social and HCP social tasks are also highly correlated since their functional signatures both pertain to the social judgment of motion-specific properties of a triangle-shape clip art.

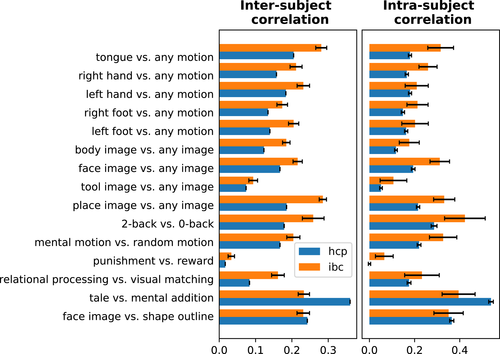

3.2 Variability of functional signatures within and between participants

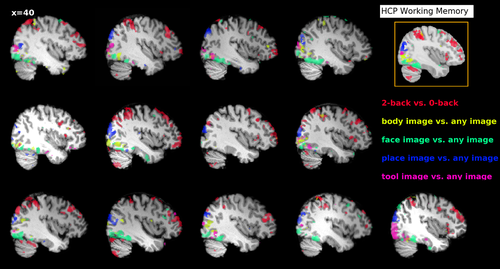

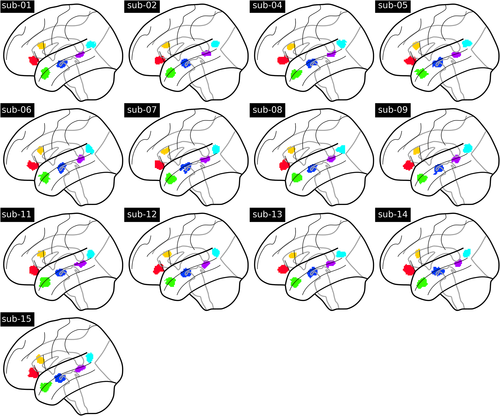

Figure 2 shows the individual functional signatures obtained for the Working Memory task adapted from the HCP protocol. It displays a qualitative visual description of the variability of such functional signatures across participants. Although the main features of functional responses are preserved at a coarse scale across individuals, there are clear differences in the precise locations of the active regions. For instance, this is the case for the place image versus any images contrast that displays an active focus in the vicinity of the transverse occipital sulcus for all participants; yet, the size of the cluster and its MNI-space position vary conspicuously among them. Similarly, the body image versus any image and face image versus any image contrasts display activity along the fusiform gyrus, as well as face image versus any image and tool image versus any image in the lateral occipital complex. However, their expressions differ across subjects, resulting into different functional preferences at the corresponding locations in MNI space. It remains to be checked whether such variations represent intrinsic between-subjects variability or simply sampling noise.

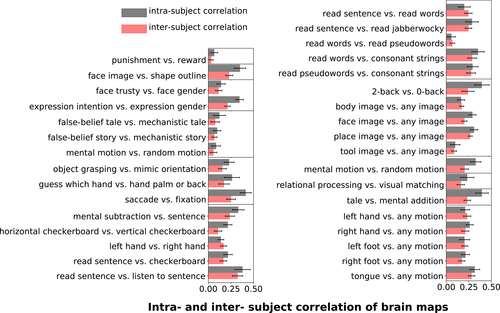

In turn, Figure 3 provides a quantitative characterization of the spatial consistency, within and between participants, of the main contrasts from each task. Consistency is measured by a similarity metric, namely Pearson correlation. The mean of the correlations between participants stands always above zero, revealing some level of spatial consistency among individual maps. Nevertheless, they are always below 0.5, which quantifies the level of noise of these maps. Importantly, the contrasts show different levels of overlap because of either the low fSNR or the large variability present in each contrast. For instance, contrasts from both ARCHI Social and HCP Social tasks, that is, false-belief story versus mechanistic story, false-belief tale versus mechanistic tale and social-interaction motion versus random motion, as well as punishment versus reward from the HCP Gambling task exhibit lower consistency than tasks involved in language or perception.

On the other hand, spatial consistency is higher at the individual level in 27/33 contrasts displayed in Figure 3. Note that, since per-session data are used to compute the individual-maps consistency, the fSNR in every map is lower for the intrasubject consistency analysis than for the intersubject consistency. These correlations also reflect imperfectly corrected PA/AP spatial distortions. Overall, the fact that maps are generally more consistent within subjects than across subjects hints at subject-specific topographies.

We have also compared intersubject consistency of the main-contrast maps (except those from the RSVP Language task) estimated from the IBC dataset and the original datasets, that is, ARCHI and HCP datasets (see Figures A1 and A2 in Appendix C). Results show that, in the large majority of the cases, considerably higher correlations were achieved using the IBC data than the ARCHI data as well as the HCP data. Intrasubject consistency was also evaluated between the IBC and HCP data and correlations are also overall higher among contrasts from the IBC dataset (see Appendix C). They thus confirm that the IBC dataset hints at good levels of fSNR—in agreement with the results stated in Pinho et al. (2018)—as well as an overall high data quality, including an adequate parametrization of the MRI acquisitions.

3.3 A dictionary of cognitive components

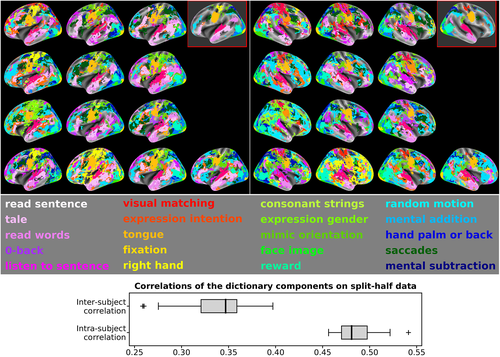

We then analyzed the topographies of 20 cognitive components obtained by decomposing, per subject, the original data of all tasks—that is, 51 main-contrast maps—using sparse dictionary learning. These individual topographies are displayed as spatial maps (see top section of Figure 4), wherein each map represents the functional profile of a component in each subject and hemisphere (i.e., maps of the top-left and top-right panels refer to the left and right hemispheres, respectively). According to Smith et al. (2009) and given the total number of IBC contrasts, k = 20 represents a consensual number of components to feature this study. A larger number of components were deliberately not chosen for the sake of readability of the present results. These components synthesize the cognitive information across all contrasts, making between-subject comparison easier. They were named according to the main conditions of the contrasts that obtained the largest value in their functional fingerprint. Such labeling was only possible due to the use of task data. The functional fingerprints of the components are provided as Supplementary Material.

Since most of the activations depicted in the original contrast maps are located in the cortex, surface-based analysis was herein employed in order to enable a fine functional parcellation of the cortical structures from the individual topographies (see Section 2.7.1 for details).

The two red-framed brain maps, displayed at the right-top corner of each panel in Figure 4, show the median map of the components across individuals, that is, each vertex has the label corresponding to the strongest component observed in—at least—half of the participants. These median maps thus provide a robust consensus model of the topographies obtained across subjects. Overall, tasks consistently map brain networks across participants. Nevertheless, one can still observe differences between subjects that are worthy of notice. For instance, components tagged as math, saccades and consonant strings are observed in similar brain regions across subjects, but one typically dominates the others. In other words, their spatial representations compete across subjects. While their outline is broadly similar, they reveal in detail notable differences at high resolution.

To assess the stability of the dictionary, the dataset was split into two halves, according to the phase-encoding direction parameter. The split-half reproducibility of the 20 components was measured as correlations of the individual topographies both within and between subjects. The topographies were, in this case, obtained through the contrast z-maps estimated from the “PA” and “AP” runs of each task. Intrasubject stability was evaluated through the distribution of the correlations between PA- and AP-related topographies in every subject. On the other hand, intersubject stability was estimated through the distribution of correlations between PA- and AP-related topographies within pairs of subjects. The results, displayed at the bottom section of Figure 4, show higher correlations estimated from intrasubject data than intersubject data, highlighting that the variability of such spatial representations is linked to individual differences.

Finally, it is also worthy of note that these aggregated components are more stable than the original contrast maps (see Figure A1 of Appendix C). Overall, means of the distributions for both intrasubject and intersubject correlations of dictionary components (see bottom section of Figure 4) are higher than means of the distributions of z-maps correlations (see Figure 3).

3.4 Reconstructing functional contrasts from different tasks

Because different conditions across tasks share the same cognitive properties, the contrasts are expected to capture commonalities resulting from the corresponding functional activations. Such commonalities can be learnt and used to predict other contrasts from tasks supposedly sharing the same cognitive properties (see, e.g., Tavor et al. (2016)). Thus, contrast maps from a target task (one contrast map at a time) are predicted from contrast maps of the training tasks. The R2−statistic was used to quantify the discrepancy between the predicted and actual maps, and the maximum of this statistic was computed across tasks.

Figure 5—top shows that a good accuracy prediction was attained throughout all regions in the brain, except in the hippocampus, superior temporal asymmetrical pit (Glasel et al., 2011; Leroy et al., 2015), precuneus, and inferior temporal gyrus. The few exceptions might be explained by either the lack of tasks targeting these regions or a reduced fSNR at these regions.

Several tasks were well predicted by other tasks (see Figure 5—bottom). Indeed, tasks whose contrasts share cognitive properties with many contrasts from other tasks—like ARCHI Standard, RSVP Language, and HCP Working Memory—received higher scores. Contrariwise, a task like HCP Motor, that yields not only on hand movements (common to other tasks) but also on foot and tongue movements—which are unique to this task—could not be as well predicted by the other tasks. At last, this analysis was repeated, but with subjects permuted between train and test, potentially breaking the fine-grained structure of brain responses. Results show a clear decrease of the proportion of the predicted voxels, confirming that topographies are subject-specific. Interestingly, such decrease was not very evident for the HCP Motor task, highlighting that low-level cognitive processes are less sensitive to spatial variability across individuals. Chance level was computed for all tasks with and without permutations of subjects between train and test. In all cases, its value was zero.

Overall, results from Figure 5 highlight two important findings. First, brain responses in different contrasts underlie a latent structure, allowing for the prediction of a response to a given task in a new subject; this structure is, in turn, conditional to other brain responses. Second, the topographic organization of these components is subject-specific.

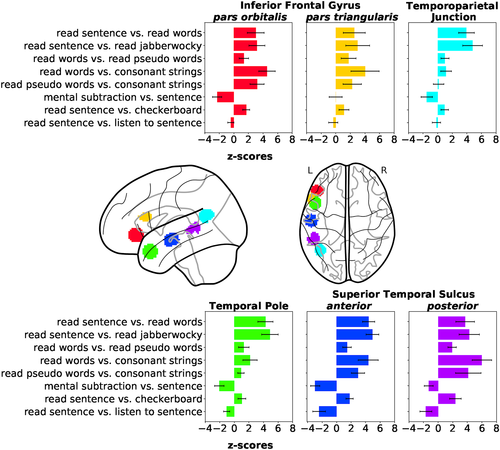

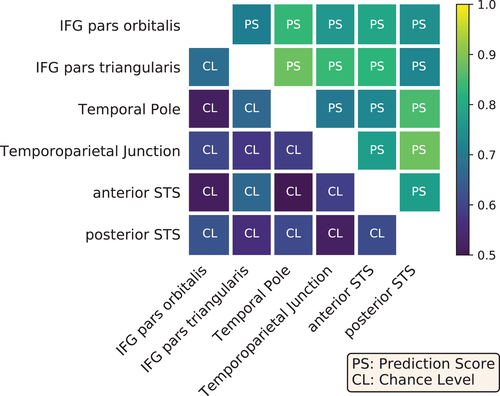

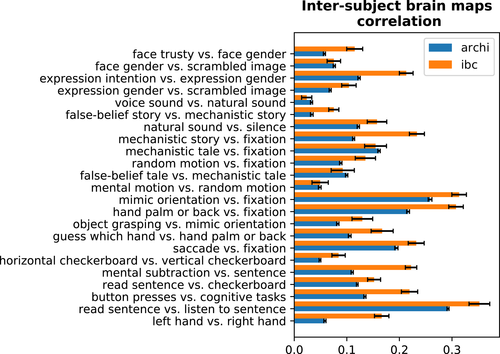

3.5 Functional mapping of the language network

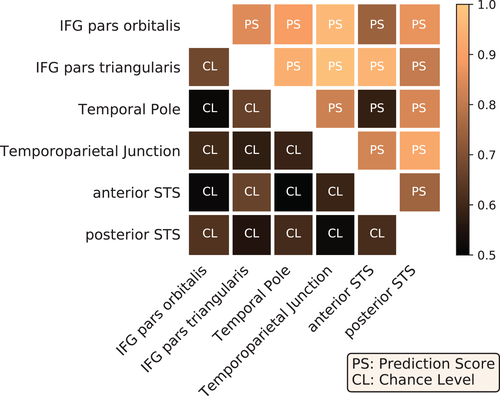

As several contrasts cover the same psychological domains, the IBC dataset provides the appropriate framework to derive a fine and unambiguous characterization of brain regions with respect to cognition. To showcase the benefits resulting from contrast-maps accumulation, we thus investigated the cognitive profile of a set of brain regions known to be linked to language mechanisms. These regions-of-interest refer to: (a) the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) pars orbitalis and (b) pars triangularis, (c) the left temporoparietal junction, (d) the left temporal pole, (e) the left anterior, and (f) posterior superior temporal sulcus (STS). They were subsequently made subject-specific using the dual-regression approach described in Section 2.7.8. The maps of their projections onto individual templates are provided in Figure A3 of Appendix D.1. To illustrate the specific function of these regions, Figure 6 shows the activations elicited by—linearly independent—contrasts selected from the ARCHI Standard and RSVP Language tasks, whose effects-of-interest are related to language.

The two portions of the left IFG reveal greater responses to read sentence than read words, as highlighted in the selected contrast from the RSVP Language task, although effects are significant in both cases. Worthy of notice are the effects obtained in all regions for the contrast sentence5 versus mental subtraction (reverse contrast of mental subtraction vs. sentence in Figure 6), except in the left IFG pars triangularis. These results indicate higher level of activation in these regions, but in the left IFG pars triangularis for the general-domain semantic condition (i.e., sentence) than the math-specific semantic condition (i.e., mental subtraction). Indeed, Amalric and Dehaene (2016) report several regions of the language network activating less for math statements than nonmath statements. On the other hand, the left IFG pars triangularis was shown to be specifically implicated in arithmetic processes (Andin, Fransson, Rönnberg, & Rudner, 2015).

The left temporoparietal Junction and left temporal pole show greater responses in the read sentence versus read words and read sentence versus read jabberwocky contrasts, revealing their involvement in the modulation of combinatorial semantics. In fact, the absence of activations in the left Temporoparietal Junction for the remaining contrasts highlights that this region is specifically responsive to sentence comprehension. Opposite effects in the read words versus read pseudowords, read words versus consonant strings and read pseudowords versus consonant strings contrasts indicate low responsiveness to lists of words. Additionally, the left Temporal Pole also exhibits a high level of activation in the listen sentence versus read sentence contrast, which reflects some sensitivity to auditory stimuli.

At last, the left STS exhibits overall strong effects to different levels of specificity in language mechanisms, given its high level of activation in most of the contrasts. Yet, its posterior portion is more responsive to list of words than the anterior, as shown in the contrasts read words versus read pseudowords, read words versus consonant strings and read pseudowords versus consonant strings. Contrariwise, its anterior portion is more responsive to combinatorial semantics than the posterior, as shown by the contrasts read sentence versus read words and read sentence versus read jabberwocky. Similarly to the left Temporal Pole, both portions of the left STS are responsive to auditory stimuli.

All regions were equally sensitive to the read sentence versus checkerboard contrast, highlighting the low level of specificity of this contrast for language-related mechanisms.

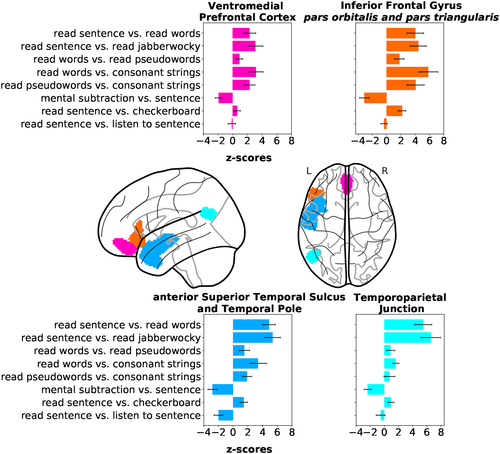

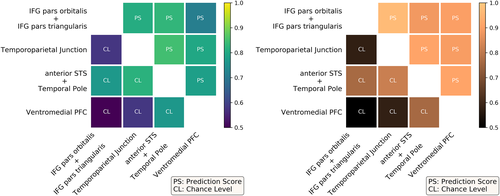

Overall, the variety of contrasts referring to language highlights differences in the functional specialization of the aforementioned regions-of-interest. To assess the statistical significance of these differences, we tested whether voxels could be reliably classified as belonging to one of these regions, based on their functional activation in the given contrasts. Figure 7 presents the prediction scores obtained between pairs of regions against their baselines, that is, the corresponding chance levels of such predictions. All scores outperformed the chance level, although the classifier between IPS pars orbitalis/pars triangularis was close to chance. In order to generalize our conclusions to other cognitive domains and demonstrate the benefits of accumulated task data, the same experiment was also performed with data extracted from all main-contrast maps obtained from the entire dataset. The decoding performance was slightly higher (see Figure A4 in Appendix D.2, which shows that including a wider range of cognitive domains improved the functional characterization of the regions-of-interest.

To further evaluate the generalizability of these results, we conducted the same analysis in another set of regions-of-interest, also pertaining to the language network but extracted from functional signatures obtained from a larger cohort. Concretely, the group-level contrast story versus math of the HCP Language task (for more information about this task, consult Section 2.4.2), referring to a subset of the HCP900 dataset (n = 786), was used to define functional regions participating in language-related mechanisms. A complete description of the procedures concerning regions' extraction can be found in Appendix D.3. This set of regions-of-interest partially overlaps with the previous one. The left Temporoparietal Junction was clearly isolated. Besides, it was possible to extract the left anterior STS as well as the left Temporal Pole but we were not able to dissociate both into two distinct regions; similarly, the results allowed the extraction of the IFG, yet comprising both pars orbitalis and pars triangularis. We further identified the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex, usually reported to be involved in semantic integration. In summary, the cognitive profiles obtained are consistent with the previous ones (see Figure A5 in Appendix D.3) and differences between them are statistically significant, since all prediction scores between pairs of regions were higher than chance (see Figure A6 in Appendix D.3).

The taskwise structure of the IBC dataset thus opens a new type of analysis, whereby brain-region profiles can be compared in order to highlight their functional specificity.

4 DISCUSSION

High-resolution brain images allow for fine-grained contrast mapping and detailed characterization of brain networks at the individual level. However, these maps only overlap partially at the group level, making it hard to build a functional template from all of them. On the other hand, system-level analysis of cognitive functions requires pooling data from multiple tasks.

This article lays the ground for individual functional atlasing, a novel analytic approach that requires a specific strategy to avoid circular reasoning, that is, delineating different topographies from functional contrasts is not sufficient to state that subjects differ regarding these contrasts. Because it aims at providing quantitative insights about individual differences of elementary processes in cognition, deep phenotyping of behavioral responses becomes crucial in such approach. To this end, it is thus important to ensure that individual data are comparable to existing resources, that is, that the contrasts used herein reproduce those of previous large-scale studies. Thence, an essential step is to analyze the consistency of functional signatures across regions. After a qualitative inspection of some contrasts in a given task, that provided propitious results, we scaled up the analysis; a relatively coarse, network-level structure was extracted from all tasks using dictionary learning, as means to obtain a global picture of the between-subject consistency of the functional patterns. Third, we controlled the predictive power of these individual topographies by reconstructing contrast maps organized by tasks, using cross-validation across individuals. Successful predictions, in particular within subjects, strictly confirm the above intuitions. We then illustrated the practical significance of this individualized mapping approach, by showing how to adapt population-level regions-of-interest to individuals. This framework allows for probing unique functional profiles associated with specialized brain regions, giving the flexibility of adapting to an individual configuration and assessing functional specialization across individuals, while avoiding circular reasoning. We review all these steps in further detail over the next sections.

4.1 A small-n, yet reliable functional mapping

Fifty-one main-contrast maps were investigated in this cross-task analysis, yielding a unique high-coverage cognitive mapping. Despite the low number of subjects, group-average results are consistent with those from previous larger-scale datasets, as highlighted by the results presented on Section 3.1.

4.2 Spatial variability of functional signatures

High-resolution, individual contrast maps provide evidence of the intersubject spatial variability inherent to functional signatures associated with cognitive processes. In Figure 2, one can see, for example, the differences across participants in the cluster extent placed on a subsection of the transversal occipital sulcus, present in the contrast place image versus any images. This variability could be mitigated by normalization techniques relying on macroanatomical landmarks (Frost & Goebel, 2012) rather than MNI coordinates; this matter is subject of further investigation. Importantly, the number and diversity of contrasts allow us to quantify such variability within and between participants (see Figure 3). For instance, it shows which cognitive domains are more stable between participants. Contrasts isolating vision processes, motor performance and low-level of semantic comprehension in language (e.g., manipulation of words) are more consistent across individuals than contrasts pertaining to social cognition or theory-of-mind. Besides, spatial consistency can also be studied within subjects for every task, showing which brain networks display a low fSNR, due to for example, geometric distortions inherently associated with MRI acquisition parameters. Overall, intrasubject consistency is higher than intersubject consistency, which hints at subject-specific topographies.

4.3 Topographies of cognitive components

The taskwise structure of the IBC dataset can support the investigation of common functional profiles or fingerprints and link them to experimental tasks. Here, we use dictionary learning to extract these functional profiles in an automatic fashion. Note that, other approaches would also be possible, such as independent components analysis or clustering. Our data-driven analysis, exploiting individual topographies across tasks, highlights the intersubject variability inherent to cognitive mapping (see Figure 4). Similarly to the results in Section 3.2, intrasubject consistency was higher than intersubject consistency. Interestingly, the mean of intrasubject correlation for all components (see bottom section of Figure 4) is about twice the intrasubject consistency registered for the contrast maps themselves (see Figure 3). Obviously, more contrasts lead to less noisy, hence more reproducible components.

Note that we chose here to arbitrarily estimate 20 components to represent the data. There is no reason to believe that this is an optimal number. We defer a more thorough discussion on this topic to future work, bearing in mind that the level of description always depends on the scientific question posed. We also note some alternative modeling choices that have been proposed in the literature, for example, relying on group structure (Varoquaux et al., 2013) or spatial regularization (Abraham, Dohmatob, Thirion, Samaras, & Varoquaux, 2013). These algorithms contain some hyperparameters that are hard to set in practice, and their convergence is computationally challenging. Hence, we have decided to rely on a simpler, data-driven approach, expecting that the accumulation of contrasts obviates the need for regularization terms.

At last, we opted to map the individual topographies on the surface, since most of the activations in the original volume-based contrasts are located in the cortex. The importance of surface-based mapping comes to the forefront when one aims at individual-specific localization in the upper cortical areas of the brain and, thus, surface-based cortical registration becomes relevant toward setting a common system of topographical representation on the surface. Recent methods based on geometric features derived from functional and diffusion imaging, such as spherical daemons (Yeo et al., 2010) or multimodal surface matching (Robinson et al., 2014), are promising in regards to deliver a better surface alignment because of a greater sensitivity to a wider variety of surface descriptors. Therefore, we acknowledge the possibility to integrate, in the future, such steps in the preprocessing pipeline.

4.4 Prediction of contrasts within the dataset

Since many contrasts share the same cognitive components, they display overlapping functional patterns. This shared variability can be learnt and used to predict other contrasts. Such a successful prediction reveals the existence of a latent structure underlying them (see Figure 5). Additionally, predictions are higher when subject identity is not randomly shuffled, highlighting once again that functional anatomy varies across subjects.

Interestingly, this experiment, together with the reproduction of contrast maps from the ARCHI and HCP datasets (see Figure 1), implies that some brain maps could be transferred from IBC to these aforementioned datasets. For instance, we hypothesize the possibility of predicting the topographies of the HCP participants from the individual contrast maps of the IBC-ARCHI or RSVP-language tasks.

4.5 Cognitive regional profiles of the language network

The taskwise organization of the dataset also opens the possibility to investigate the functional profiles of brain regions linked to cognitive domains covered by the contrasts (see Section 3.5). For instance, the results shown in Section 3.5 can identify which regions elicit effects modulated by word-level (e.g., left posterior STS) and sentence-level semantics (e.g., left Temporoparietal Junction and left Temporal Pole). On the other hand, effects modulated by syntax are difficult to isolate in the context of brain mapping. Some studies have suggested that syntactic processing is distributed throughout an ensemble of brain regions that support high-level linguistic processing. Therefore, they cannot be separated from other aspects regarding language comprehension, like lexico-semantic processing (Blank, Balewski, Mahowald, & Fedorenko, 2016), overall suggesting that the language network might be more strongly concerned with meaning than structure (Siegelman, Blank, Mineroff, & Fedorenko, 2019). Yet, as an attempt to address this issue, we plan to integrate, in a future release, a naturalistic language-comprehension paradigm, dedicated to syntactic-composition modulation (Bhattasali et al., 2019). The more tasks are included in the dataset, the greater the richness of the contrasts that can be used to not only disambiguate the cognitive role of functional regions but also delineate finer demarcations of their anatomical boundaries.

4.6 Limitations

According to the structure of the IBC dataset, the analysis is limited to 13 subjects. This is not enough if one were to report populations effects, yet it leaves the possibility of conducting parallel analysis on 13 unique brains and highlight commonalities among them. The question of deriving a sensible group-level model for this dataset remains thus open.

4.7 Toward more individualized models of brain function

One possible extension of the present work relates to the development and testing of feature-based alignment approaches (Haxby et al., 2011; Sabuncu et al., 2010) that can match specific properties of functional brain regions, such as cognitive responses or connectivity. They can thus be used to improve the estimation of functional templates in the presence of conspicuous between-subject variability, as demonstrated in the recent work by Bazeille, Richard, Janati, and Thirion (2019). Additionally, Bijsterbosch et al. (2018) have shown that most of the relevant cross-subject differences, identified through brain imaging, are rooted in the topography of their individual maps. These findings suggest that future investigations on the latent structure of individual contrast maps may contribute to improving the analysis of between-subject characteristics in brain imaging. Nevertheless, an important question still remains: what is the most appropriate method to achieving these correspondences?

4.8 Ongoing taskwise development of the Individual Brain Charting dataset

The collection of new data in IBC is ongoing until year 2022 and more releases are planned over the upcoming years. The second and third releases have recently been made publicly available—source data are available in OpenNeuro under the data accession ds0026856 and derivatives in NeuroVault with the id collection 6618 7— and they comprise a variety of cognitive tasks. Like the first release, the second release covers tasks on both lower-order and higher-order cognitive functions, such as mental-time travel (Gauthier & van Wassenhove, 2016a, 2016b), positive-incentive value (Lebreton, Abitbol, Daunizeau, & Pessiglione, 2015), theory-of-mind and pain matrices (Dodell-Feder, Koster-Hale, Bedny, & Saxe, 2011; Jacoby, Bruneau, Koster-Hale, & Saxe, 2016; Richardson, Lisandrelli, Riobueno-Naylor, & Saxe, 2018), numerosity (Knops, Piazza, Sengupta, Eger, & Melcher, 2014), self-reference effect (Genon et al., 2014), and speech recognition (Campbell et al., 2015). The third release is dedicated instead to an extensive data collection tackling the visual system; it is concerned with tasks on visualization of naturalistic scenes (Huth, Nishimoto, Vu, & Gallant, 2012), classic retinotopy, and movie watching (Haxby et al., 2011). The fourth release is currently in preparation and it includes a tonotopy task (Santoro et al., 2017) as well as two batteries of localizers (Aron, Behrens, Smith, Frank, & Poldrack, 2007; Bissett & Logan, 2011; Crump, McDonnell, & Gureckis, 2013; Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974; Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz, & Posner, 2002; Figner, Mackinlay, Wilkening, & Weber, 2009; Hamame et al., 2012; Kaller, Rahm, Spreer, Weiller, & Unterrainer, 2011; Kirby & Maraković, 1996; Ossandon et al., 2012; Otto, Skatova, Madlon-Kay, & Daw, 2014; Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2012; Saignavongs et al., 2017; Schneider & Logan, 2011; Shallice, 1982; Stroop, 1935; Vidal et al., 2010; Ward & Allport, 1997) addressing many other cognitive modules, such as: stimulus salience, working memory, visual object categorization, audio perception, risk-associated decision making, motor inhibition, planning and vigilance. Our ultimate goal is to achieve a comprehensive brain coverage of functional signatures, associated with a large variety of mental functions, by the end of the project.

5 CONCLUSION

Our results show that the application of rich taskwise datasets is necessary in studies concerned with cognitive mapping and individual modeling of the human brain.

Tasks adapted from former projects are in overall agreement with the ones reported by the original studies. Therefore, this study advocates the principles of data-sharing and reproducibility in neuroscience, as means to achieving transparency in research practice and consistency of results across time. Raw data and data derivatives of the first release of the IBC dataset have been made available in the public repositories of OpenNeuro and NeuroVault, respectively. In particular, individual and unthresholded z-maps in NeuroVault were extensively used to deliver the results of the present article. They are thus intended to serve as a valuable tool for the community and complement mega-analytic and meta-analytic studies dedicated to the functional examination of cognition in the human brain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Framework Program for Research and Innovation under Grant Agreement No. 945539 (Human Brain Project SGA3) and Grant Agreement No. 785907 (Human Brain Project SGA2). A battery of tasks developed by the HCP were reproduced in this study. The authors are thus thankful to the coordination facility of HCP for having made publicly available the corresponding behavioral protocols. The authors are also thankful to the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, University of Minnesota for having kindly provided the MB Accelerated EPI Pulse Sequence and Reconstruction Algorithms. At last, the authors especially thank all volunteers who have accepted to be part of this challenging study, with many MRI-repeated scans over a long period of time.

Endnotes

Appendix A.: DEMOGRAPHIC DATA OF THE PARTICIPANTS

Table A1 summarizes the demographic profile of the extended version of the IBC dataset, which accounts for 13 participants in total.

For more information about the profile of the participants and procedures undertaken during recruitment, consult Pinho et al., 2018.

Appendix B.: DESCRIPTION OF THE BEHAVIORAL CONDITIONS INCLUDED IN THE TASKS

This section provides a summarized description of the tasks featuring the first release of the IBC dataset. For a full description of the tasks, consult Pinho et al. (2018).

1 ARCHI tasks

The ARCHI tasks consist of a series of localizers targeting several cognitive processes of interest.

1.1 ARCHI standard

This multifunctional localizer—dedicated to fast brain mapping—isolates a variety of elementary mental functions, ranging from low-level to high-level cognition. They are concerned with visual perception, motor actions, reading, language comprehension, and mental calculation. The task is organized as a fast event-related paradigm, composed of trials including 10 different experimental conditions. These conditions are listed and described in Table A2.

1.2 ARCHI spatial

This task isolates neurocognitive mechanisms concerned with visual orientation and body representation in space. Its paradigm is organized in terms of five conditions; events per condition are combined and displayed in blocks. Conditions are listed and described in Table A3.

1.3 ARCHI social

This task examines mental functions about social representations and social identity, such as animacy perception, narrative comprehension, mentalization, and theory-of-mind. Its paradigm is organized in terms of eight conditions; events from subsets of different conditions are combined and displayed in blocks. Conditions are listed and described in Table A4.

1.4 ARCHI emotional

This task isolates mental functions involved in the perception of emotions, from facial to eye expressions, required for judging temper or subjective trustworthiness. Its paradigm is organized in terms of five conditions; events from subsets of different conditions are combined and displayed in blocks. Conditions are listed and described in Table A5.

2 HCP tasks

These set of tasks were adapted from the task-fMRI paradigms used in HCP, yet with some timing differences and more trials for a subset of them (consult Pinho et al. (2018) for further details).

2.1 HCP emotion

The main purpose of this task is to isolate neurocognitive mechanisms involved in the perception of fear and anger, from the visual comparison between generic geometric shapes and affective facial expressions. The paradigm is organized in terms of two conditions; events of these conditions are combined and displayed in blocks. They are listed and described in Table A6.

2.2 HCP gambling

The aim of this task is to capture effects concerned with incentive as well as aversive salience. The paradigm is organized in eight blocks, each of them composed of eight events. Every event consists of playing a gambling game, whose goal is to guess whether the next number to be displayed—ranging from one to nine—will be smaller or larger than five. Feedback is given afterward and conditions are defined according to the reward or loss experienced after a given outcome (see Table A7).

2.3 HCP motor

The aim of this task is to isolate contralateral and ipsilateral motor representations of the foot, hand, and tongue in the motor cortex and cerebellum, respectively. The paradigm is organized in terms of five conditions concerning left foot, right foot, left hand, right hand, and tongue; events of sets of different conditions are combined and displayed in blocks. Conditions are listed and described in more detail in Table A8.

2.4 HCP language

This task aims at localizing effects involved in narrative comprehension and auditory sentence recognition. The paradigm comprises two conditions, wherein each of them is presented in a full block, one at the time. Conditions are listed and described in Table A9.

2.5 HCP relational

This task is intended to isolate neurocognitive mechanisms pertaining to relational and feature comparison as well as visual form recognition. It employs a relational match-to-sample paradigm, featuring a second-order comparison of relations between two pairs of objects. The paradigm comprises two conditions, wherein each of them is presented in a full block, one at the time. Conditions are listed and described in Table A10.

2.6 HCP social

This task aims at providing evidence for task-specific brain activation implicated in social cognition. Similarly to the ARCHI social task (see Appendix B.1.3), this task is intended to tackle functional mechanisms related to social cognition, namely animacy perception, narrative comprehension, mentalization, and theory-of-mind. The paradigm comprises two conditions, wherein each of them is presented in a full block, one at the time. Conditions are listed and described in Table A11.

2.7 HCP working memory