Give a nudge a shot: NUDGE-FLU bridging the cardiovascular quality chasm

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Journal of Heart Failure or of the European Society of Cardiology. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2913

This article refers to ‘Electronic nudges to increase influenza vaccination uptake among patients with heart failure: A pre-specified analysis of the NUDGE-FLU trial’ by N.D. Johansen et al., published in this issue on pages 1450–1458.

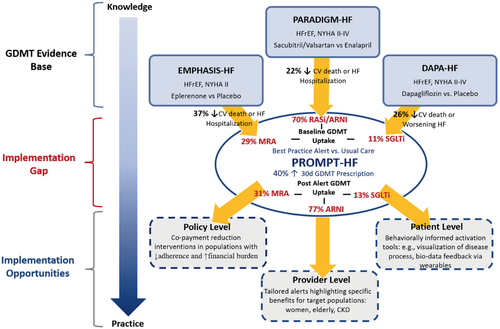

Humans are complicated and change is hard. Despite the best intentions of clinicians, the value-action gap in healthcare is, at least in part, a manifestation of cognitive biases that impact physician and patient decisions alike. Medicine has historically relied on passive diffusion and dissemination of evidence through clinical practice guidelines with a considerable lag (17 years on average) in the adoption of evidence-based interventions into routine clinical practice.1 This highlights the necessity to shift to active and evidence informed processes of implementation with insights from behavioural economics offering a promising tool for the way forward (Figure 1).

The inception of the first ‘Nudge Unit’ by the British government highlighted the utility of combining insights from behavioural economics with rapid testing to create evidence informed policy instruments. The team demonstrated how reciprocity messaging could increase organ donation registration and social norms comparisons could increase charitable donations. Behavioural insights have since been increasingly leveraged in corporate environments, within governments, as well as by intergovernmental organizations such as the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development and the World Health Organization. Many hospitals invariably use behavioural interventions to modify patient behaviour and improve clinical decision support.2 However, the integration of dedicated behavioural insights teams to inform the targeted use and evaluation of such interventions has been less intentional at the level of the health system.

The field of behavioural economics lies at the convergence of psychology and conventional economics and seeks to explain human behaviour.3 Essentially, why do we do what we do? Dual processes of thought (system 1 and 2) operate concurrently to inform decision making.4 System 1 is automatic, quick and largely unconscious while system 2 is slower, systematic and cognitively effortful. Contrary to the standard economic model which assumes that humans are purely rational, behavioural economists posit that rationality is bounded due to finite cognitive capacity (we only have so much brain power), time and information.4 Therefore, humans rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to make decisions which may result in predictable cognitive biases.5 This partly explains why clinician prescription of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) remains suboptimal and why proven preventive health measures, from exercise to influenza vaccination, are subject to misalignment between best intention and action.

Patients with cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities are at increased risk for influenza and its complications. Viral infections including those secondary to influenza may trigger acute CV events. Indeed, respiratory infections represent one of the most common precipitants of acute decompensated heart failure (HF).6 Although influenza vaccination is associated with reductions in all-cause and CV specific mortality among patients with HF, vaccination rates remain suboptimal.7 Patients with CV disease and HF specifically, represent a target group for intervention.

Cognitive biases can be leveraged to optimize decision making through behavioural interventions such as nudges. According to Thaler and Sunstein a ‘nudge’ is ‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives’.3 On the spectrum of behavioural interventions, nudges and educational campaigns are considered ‘soft’ instruments in comparison to mandates or taxes which are considered ‘hard’ measures. As it relates to health behaviours, soft instruments such as nudges, which guide individuals to make optimal choices and increase opportunities to act on those choices, tend to have higher public acceptability.8 This is an important consideration for influenza vaccination, particularly following the variable consequences of COVID-19 vaccination mandates on public trust.

How can nudges be applied to improve health at scale? NUDGE-FLU, a nationwide, pragmatic, cluster randomized controlled trial, is an exemplary model.9 This study assessed the effect of nine electronically delivered letters employing various nudging strategies on influenza vaccination rates among 964 870 Danish citizens aged >65 years. The CV ‘gain framed’ letter highlighting the CV benefits of vaccination and ‘repeated letter’ hot state priming were the two strategies found to significantly increase vaccination rates.

In this issue of the Journal, Johansen and colleagues report on a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the NUDGE-FLU trial among patients with HF.10 The authors highlight suboptimal rates of vaccination in patients with HF which was most prominent among those aged <65 years with less than half of patients receiving vaccination. Letters employing CV ‘gain framing’ and ‘repeated’ nudging strategies consistently improved vaccination rates irrespective of underlying HF status. The effect of both successful strategies did not appear to be modified by HF duration. Importantly, the intervention did not result in any un-unintended effects on longitudinal HF GDMT use.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the NUDGE-FLU trial lies in three unique design elements that may or may not apply to other regions: the availability of a widely used nationwide digital communications platform, high levels of public engagement, and ubiquitous health registries. Together this has enabled the study power (through enrolment of nearly 1 million participants) and granularity of data (extracted from integrated health system data) to begin to understand how the effects of the nudge intervention may be modified by context and within specific groups. Thus far, this has included dedicated pre-specified analyses in patients with CV disease11 and specifically HF.10 This is highly valuable since generalizability remains a major limitation of such studies and the authors should be congratulated for this endeavour.

While the effect sizes of nudge interventions have been impressive relative to landmark clinical trials (Figure 1) which inform cardiology clinical practice guidelines, the effects are heterogeneous. For instance, a best practice alert improved rates of HF GDMT prescription among outpatients in PROMPT-HF12; however, the same intervention was unsuccessful when employed in the inpatient setting in PROMPT-AHF.13 The divergent results of these two trials underscore the importance of evaluating interventions in multiple contexts. Low value alerts may result in frictions to patient care, negatively impact the review of important alerts and contribute to physician burnout. It is equally important to understand which interventions do not work in order to prevent the well-intentioned ‘nudge’ from becoming ‘sludge’.14

Behaviours are linked, consciously and subconsciously, and behavioural interventions may have unintended consequences or ‘spillover effects’ on other behaviours.15 When designing and testing behavioural nudges it is important to consider and assess both intended and unintended consequences. Although the study was not specifically powered to detect such differences, the present analysis is one of the few nudge studies which included an evaluation for such spillover effects in CV care. One may hypothesize that engaging in a perceived CV benefitting behaviuor such as influenza vaccination may have had either a permitting or promoting spillover effect on longitudinal patterns of GDMT use. In a permitting spillover, the satisfaction gained from engaging in one healthy behaviour (vaccination) may reduce the urgency in another equally important area of health (HF medical therapy).15 On the other hand, a preference to act consistently with the healthy act of vaccination may result in a promoting spillover effect on HF medical therapy.15 While there was a lower rate of influenza vaccination observed in patients that were on the lowest levels of HF GDMT, the electronic letter nudges themselves did not influence longitudinal GDMT use.

Multiple factors impact population ‘nudgeability’ or receptiveness to the influence of a nudge including pre-existing preferences.16 The effect size of the intervention in the overall Danish population as well as in the subgroup of HF patients in NUDGE-FLU were relatively modest and may reflect high baseline rates of vaccination (80%) in the older (age ≥65 years) population that was studied. NUDGE-FLU demonstrated an accentuated effect of the CV gain-framed letter in patients who were not vaccinated in the prior season compared to those that had received vaccination.9 As highlighted in the present report and mirrored in estimates in other countries, vaccination uptake was considerably lower in patients aged <65 years compared to those ≥65 years. Therefore, this younger population may represent a more ‘nudgeable’ target subgroup and is an important area for similar future study.

Beyond influenza vaccination, several studies have demonstrated the potential for behavioural interventions to optimize care delivery more broadly in cardiology (Table 1).12, 17-25 To sustainably improve patient outcomes, health system leadership must deliberately think like choice architects as one component of innovation. The MINDSPACE framework, used in public policy, summarizes the key elements that drive behaviour in various contexts and offers practical insights on opportunities for quality improvement (Table 1). Opportunities to systematically modify choice environments and evaluate outcomes to inform best practice in care delivery are increasingly available via digital platforms not only at the hospital level but even the regional or country level (as demonstrated by Johansen et al.). Further understanding the optimal timing and setting of nudge delivery as well as the potential role of nudges in reducing disparities in care are important next steps. In addition, machine learning tools could be leveraged to amplify nudge effects by delivering tailored nudges to patients and/or clinicians according to their behavioural profile: ‘precision nudging’. Overall, insights form behavioural economics have important implications as policy instruments not only for public health but also for closing the quality chasm in CV care.

| Historical example | Behavioural economics principlea | Opportunity for future study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality gap | Intervention | ||

| Health promotion by barbers improved BP control among black male barbershop patrons17 |

Messenger We are heavily influenced by who communicates information |

Suboptimal SGLT2i prescription for patients with concomitant CAD and DM by cardiologists | SGLT2i prescription reminders embedded in PCI reports by interventional cardiologists |

| Loss-framed financial incentives increased step-counts in patients with ischaemic heart disease18 |

Incentives Our response to incentives are shaped by predictable mental short cuts, e.g. desire to avoid losses |

CV risk factor modification | Social incentives through gamification for target HbA1c and LDL-C achievement |

| Peer comparison prescribing feedback increased rates of statin prescription19 |

Norms We are strongly influenced by what others do |

HF GDMT prescription and adherence | Tiered patient peer comparison feedback for GDMT uptake |

| Opt-out defaults increased cardiac rehabilitation referral rates20 |

Defaults We ‘go with the flow’ of pre-set options |

Surveillance for subclinical LV dysfunction in oncology patients undergoing cardiotoxic chemotherapy | Opt-out defaults for biomarker and LV function surveillance for patients undergoing cardiotoxic chemotherapy |

| Best practice alerts increased 30-day GDMT prescription in HF12 |

Salience Our attention is drawn to what is novel and seems relevant to us |

Suboptimal prescribing of HF GDMT in patients with CKD | Gain-framed prompts highlighting high risk and greater relative benefits for HF GDMT prescription in patients with CKD and HF |

| Visualization of asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis improved CV risk factor burden at 1 year21 |

Priming Our acts are often influenced by subconscious cues |

HF GDMT prescription and adherence | Visualization of personal LV function for patient activation to increase perception of urgency for medical therapy |

| Anti-smoking graphic health warnings improved smoking cessation and abstinence22 |

Affect Our emotional associations can powerfully shape our actions |

Disproportionately low emphasis on CV risk prevention relative to cancer diagnosis despite elevated CV risk in cancer survivors | Presenting CV risk assessments to cancer survivors to balance risk perception of heart disease relative to malignancy |

| Pre-commitment to physical activity goal (plus gamification intervention) increased daily step count23 |

Commitments We seek to be consistent with our public promises |

Under-enrolment of women and minorities in CV RCTs which inform clinical practice guidelines | Pre-trial site PI target enrolment pledges to increase representation of women and minorities in CV trials |

| Cost transparency of laboratory tests at the time of ordering reduced laboratory ordering rates24 |

Ego We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves |

Large environmental footprint of physician prescribing of in-person visits with downstream health consequences | Display carbon footprint of equivalent visit choices to encourage eco-friendly prescribing |

- BP, blood pressure, CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CV, cardiovascular; DM, diabetes mellitus; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HF, heart failure; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LV, left ventricular; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PI, principal investigator; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SGLT2i, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor.

- a Adapted from the MINDSPACE framework for influencing behaviour in public policy.25

Conflict of interest: S.C. has nothing to disclose. J.A.E. reports research support for trial leadership from Bayer, Merck & Co, Novo Nordisk, Cytokinetics, Applied Therapeutics, American Regent; honoraria for consultancy from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Bayer, Novartis; and serves as an advisor to US2.ai.