Health-related quality of life across heart failure categories: associations with clinical characteristics and outcomes

The institution where work was performed: Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Abstract

Aims

The study aims to examine characteristics and outcomes associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved, mildly reduced and reduced ejection fraction (EF) (HFpEF, HFmrEF and HFrEF).

Methods and results

Data on HRQoL were collected in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF; 2000–2021) using the EuroQoL 5-dimensional visual analogue scale (EQ 5D-vas). Baseline EQ 5D-vas scores were categorized as ‘best’ (76–100), ‘good’ (51–75), ‘bad’ (26–50) and ‘worst’ (0–25). Independent associations between patients' characteristics and EQ 5D-vas, as well as between EQ 5D-vas and outcomes were assessed. Of 40 809 patients (median age 74 years; 32% female), 29% were in the ‘best’, 41% in the ‘good’, 25% in the ‘bad’ and 5% in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas categories, similarly distributed across all EF categories. Higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class was strongly associated with lower EQ 5D-vas regardless of EF categories, followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking, body mass index, higher heart rate, anaemia, previous stroke, ischaemic heart disease, use of diuretics and living alone, whereas higher income, male sex, outpatient status and higher systolic blood pressure were inversely associated with lower EQ 5D-vas categories. Patients in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category as compared with the ‘best’ had the highest risk of all-cause death [adjusted hazard ratios 1.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.64–2.37 in HFrEF, 1.77, 95% CI 1.30–2.40 in HFmrEF and 1.43 95% CI 1.02–2.00 in HFpEF].

Conclusions

Most patients were in the two highest EQ 5D-vas categories. Higher NYHA class had the strongest association with lower EQ 5D-vas categories, across all EF categories. Patients in the worst EQ 5D-vas category were at the highest risk of mortality.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is associated with high mortality and hospitalization rates.1 It also significantly impacts physical, social and mental well-being leading to reduced health related quality of life (HRQoL).1 Compared with most other chronic diseases, HF appears to have a greater negative impact on HRQoL.2 Importantly, studies indicate that many patients with HF value improvements in HRQoL as much as, or even more than, simply living longer.3, 4 HRQoL is typically assessed through validated questionnaires, which generate scores that align with physiological parameters, changes in symptoms and alterations in clinical status.5 Lower HRQoL scores are associated with increased HF admissions and mortality.6, 7

Despite substantial evidence demonstrating the impact of HRQoL on prognosis in HF patients, less is known about characteristics associated with HRQoL and its prognostic impact, in particular across the different EF categories. Comorbidity profiles, prognosis and treatment decisions differ in patients with HF with reduced versus mildly reduced versus preserved ejection fraction (EF) (HFrEF vs. HFmrEF vs. HFpEF). HFmrEF overall resembles HFrEF, with more male patients, younger age, higher prevalence of ischaemic heart disease and primarily cardiovascular (CV) outcomes, whereas HFpEF appears more distinct, with more female patients, older age, prevalent hypertension and non-CV outcomes.8-11 Most previous studies of HRQoL in HF have focused on HFrEF. However, given the shift in the case mix of HF from HFrEF towards HFpEF, and limited disease-modifying therapies in HFpEF, incorporating HRQoL as an endpoint in clinical trials and identifying its correlates also in HFpEF are needed.12

To better characterize and compare HRQoL across all the EF categories, we sought to examine the association between HRQoL and clinical characteristics and outcomes, using the widely adopted Euro-QoL 5-dimensional visual analogue scale (EQ 5D-vas), in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF) linked with other national registries.

Methods

Data sources

SwedeHF is an ongoing large, nationwide, prospective registry of patients with HF, enrolled at hospital discharge or in the outpatient setting, regardless of EF. Details of the registry have been previously described.13 In 2021, 69 out of 76 Swedish hospitals participated in the registry, covering 32% of the HF population in Sweden, with a majority of patients being included at specialized centres rather than primary care centres.14 From 2000 to 2017, patients with HF diagnosed by their treating physician, and from 2017 onward, patients with the International Classification of Diseases; Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes I50.0, I50.1, I50.9, I42.0, I42.6, I42.7, I25.5, I11.0, I13.0 and I13.2 were enrolled in the registry.14 Approximately 80 variables are recorded at the index date including New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, clinical examination findings, findings on chest X-ray, electrocardiography, laboratory measurement and CV medications. Based on EF, patients are stratified in HFrEF defined as EF < 40%, HFmrEF as EF 40%–49% and HFpEF as EF ≥ 50%.15 The NYHA classification (Class I–IV) was assigned by the treating physician in accordance with the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute and chronic HF.1

For this analysis, SwedeHF was linked, through the Swedish personal identity number,16 with the National Patient Register and the Cause of Death Register, both managed by the National Board of Health and Welfare. From these registries, we obtained additional comorbidities according to the ICD-10 codes and the hospitalization and death outcomes. Socioeconomic data were obtained from the Longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA)17 and the Register of the Total Population (Statistic Sweden).

Establishment of SwedeHF and this analysis with linkage of the above-mentioned registries was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. Details regarding selection criteria and variable definitions are available online (https://kiheartfailure.github.io/shfdb4/, v 4.1.2).

Population

Patients enrolled in SwedeHF between 21 August 2001 and 30 December 2021, ≥18 years of age, without missing data for EF and EQ 5D-vas recorded at first registration were included in the study. Patients who died during the index hospital admission or with missing data from Statistic Sweden were excluded (Table S1). End of follow-up was 31 December 2021.

HRQoL assessment

HRQoL was measured using the EQ 5D-vas scale, which was collected during the index hospitalization or visit. The patients rated their overall perception of their health status relative to full health. Routine recording of EQ 5D-vas as a numerical scale ranging between 0 (worst HRQoL imaginable) and 100 (best HRQoL imaginable) is included in SwedeHF. Based on cut-offs used in previous studies,18 baseline EQ 5D-vas scores were categorized as ‘best’ (76–100), ‘good’ (51–75), ‘bad’ (26–50) and ‘worst’ (0–25). Self-reported symptoms of fatigue and shortness of breath were collected using a separate form within the SwedeHF registry ‘Patients' Own Registration of Lifestyle Habits and Quality of Life’. Other domains of self-reported symptoms, such as mobility, ability to maintain hygiene, engagement in main activities and pain and anxiety/depression were assessed using the EQ 5D-3L questionnaire.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes

Independent associations between baseline characteristics and EQ 5D-vas categories were evaluated. Primary outcome was all-cause death. Secondary outcomes were CV death (CVD), first HF hospitalization (HFH) and first all-cause hospitalization, separately.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were presented as percentages (proportions) and compared by the χ2 test, and continuous variables were presented as medians (quartile Q1, Q3) and were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Baseline characteristics were presented by index EQ 5D-vas categories and stratified according to EF categories. Violin plots were constructed for the distribution of EQ 5D-vas scores by age, sex, outpatients versus inpatients, HF duration, NYHA class and income strata in HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF patients.

Missing data were handled by multiple imputation (N = 10 generated databases) using mice in R.19 Rubin's rules were used for combining estimates and standard errors across the imputed datasets. Variables included in the model are indicated in Table 1. The primary outcome, all-cause death, was included as the Nelson–Aalen estimator in the model, but it was not imputed because it contained no missing values.

| Variable | Missing (%) | 76–100 | 51–75 | 26–50 | 0–25 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 11 827 (29) | 16 722 (41) | 10 304 (25) | 1956 (5) | ||

| HRQoL EQ-5D-vas | 0 | 85 [80–90] | 65 [60–70] | 50 [40–50] | 20 [10–20] | <0.001 |

| Self-reported symptoms | ||||||

| Fatiguea | 9 | <0.001 | ||||

| At rest | 199 (2) | 553 (4) | 908 (10) | 388 (22) | ||

| At moderate effort | 1166 (11) | 3724 (25) | 4396 (47) | 856 (49) | ||

| At more than moderate effort | 6174 (57) | 9091 (60) | 3656 (39) | 436 (25) | ||

| Unaffected | 3258 (30) | 1813 (12) | 413 (4) | 69 (4) | ||

| Out of breatha | 9 | <0.001 | ||||

| At rest | 68 (1) | 224 (1) | 468 (5) | 231 (13) | ||

| At moderate effort | 1375 (13) | 4137 (27) | 4760 (51) | 1006 (58) | ||

| At more than moderate effort | 6614 (61) | 9263 (61) | 3681 (39) | 429 (25) | ||

| Unaffected | 2775 (26) | 1576 (10) | 479 (5) | 81 (5) | ||

| Mobilitya | 8 | <0.001 | ||||

| Bedridden | 43 (0) | 82 (1) | 109 (1) | 40 (2) | ||

| Some problem | 2382 (22) | 6339 (41) | 6015 (64) | 1230 (70) | ||

| No problem | 8492 (78) | 8897 (58) | 3324 (35) | 493 (28) | ||

| Hygienea | 8 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cannot wash and clothe | 66 (1) | 131 (1) | 189 (2) | 77 (4) | ||

| Some problem | 370 (3) | 1122 (7) | 1624 (17) | 465 (26) | ||

| No problem | 10 479 (96) | 14 048 (92) | 7635 (81) | 1215 (69) | ||

| Main activitiesa | 8 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cannot do | 114 (1) | 330 (2) | 815 (9) | 409 (23) | ||

| Some problem | 1137 (10) | 4026 (26) | 4344 (46) | 784 (45) | ||

| No problem | 9644 (89) | 10 931 (72) | 4257 (45) | 557 (32) | ||

| Paina | 9 | <0.001 | ||||

| Severe | 221 (2) | 642 (4) | 1094 (12) | 411 (24) | ||

| Moderate | 3222 (30) | 7286 (48) | 5532 (59) | 875 (50) | ||

| None | 7424 (68) | 7326 (48) | 2767 (29) | 460 (26) | ||

| Anxiety/depressiona | 9 | <0.001 | ||||

| Severe | 86 (1) | 295 (2) | 782 (8) | 431 (25) | ||

| Moderate | 2166 (20) | 6138 (40) | 5327 (57) | 863 (49) | ||

| None | 8609 (79) | 8782 (58) | 3293 (35) | 453 (26) | ||

| Index yearb | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2000–2010 | 2044 (17) | 3245 (19) | 2056 (20) | 445 (23) | ||

| 2011–2015 | 2693 (23) | 4063 (24) | 2444 (24) | 388 (20) | ||

| 2016–2021 | 7090 (60) | 9414 (56) | 5804 (56) | 1123 (57) | ||

| Demographics/organizational | ||||||

| Sexb | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 8519 (72) | 11 342 (68) | 6502 (63) | 1288 (66) | ||

| Age (years)b | 0 | 72 [64–78] | 74 [66–80] | 75 [67–82] | 73 [64–81] | <0.001 |

| Locationb | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| Outpatient | 10 148 (86) | 14 587 (87) | 8549 (83) | 1485 (76) | ||

| Follow-up referral HF nurse clinicb | 3 | 9539 (83) | 13 453 (83) | 7965 (80) | 1446 (77) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up referral specialityb | 2 | 0.001 | ||||

| Primary care/other | 2401 (21) | 3412 (21) | 2269 (23) | 417 (22) | ||

| Hospital | 9208 (79) | 13 025 (79) | 7763 (77) | 1480 (78) | ||

| Clinical | ||||||

| Duration of HF (months)b | 2 | <0.001 | ||||

| ≥6 | 5174 (45) | 7717 (47) | 5210 (51) | 1041 (54) | ||

| LVEF (%)b | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| HFrEF | 6873 (58) | 9996 (60) | 6034 (59) | 1178 (60) | ||

| HFmrEF | 3100 (26) | 3976 (24) | 2300 (22) | 428 (22) | ||

| HFpEF | 1854 (16) | 2750 (16) | 1970 (19) | 350 (18) | ||

| NYHA classb | 7 | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 2479 (22) | 1299 (8) | 349 (4) | 51 (3) | ||

| II | 6669 (60) | 8973 (57) | 3622 (38) | 442 (25) | ||

| III | 1908 (17) | 5303 (34) | 5296 (56) | 1119 (64) | ||

| IV | 64 (1) | 140 (1) | 270 (3) | 148 (8) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2)b | 19 | 27 [24–30] | 27 [24–30] | 27 [24–31] | 27 [24–32] | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)b | 1 | 127 [115–140] | 125 [110–140] | 120 [110–140] | 120 [108–135] | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min)b | 3 | 69 [60–79] | 70 [62–80] | 72 [63–82] | 72 [64–84] | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)b | 2 | 74 [57–90] | 69 [52–87] | 66 [48–85] | 67 [48–87] | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mmol/L)c | 11 | 4.2 [4.0–4.5] | 4.2 [4.0–4.5] | 4.2 [3.9–4.5] | 4.2 [3.9–4.5] | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 7 | 138 [127–149] | 135 [124–147] | 133 [120–144] | 133 [119–146] | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 29 | 1473 [618–3140] | 1940 [844–4030] | 2254 [1000–4989] | 2453 [1030–5604] | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL)b | 29 | <0.001 | ||||

| <Median within EF | 4887 (58) | 5884 (49) | 3122 (43) | 576 (42) | ||

| ≥Median within EF | 3487 (42) | 6123 (51) | 4071 (57) | 803 (58) | ||

| NT-proBNP in AF rhythm (pg/mL) | 28 | 2190 [1279–3790] | 2488 [1423–4690] | 2912 [1700–5780] | 3000 [1632–6080] | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP in sinus/PM/other rhythm (pg/mL) | 29 | 1130 [448–2830] | 1605 [623–3761] | 1790 [700–4474] | 1958 [730–5182] | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Smokingb | 5 | 1062 (9) | 1586 (10) | 1134 (12) | 248 (14) | <0.001 |

| Diabetesb | 0 | 2487 (21) | 4115 (25) | 2940 (29) | 585 (30) | <0.001 |

| Hypertensionb | 0 | 7323 (62) | 11 048 (66) | 7000 (68) | 1290 (66) | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic heart diseaseb | 0 | 5484 (46) | 8494 (51) | 5538 (54) | 1034 (53) | <0.001 |

| Strokeb | 0 | 1173 (10) | 1984 (12) | 1474 (14) | 294 (15) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutterb | 0 | 5966 (50) | 9263 (55) | 5949 (58) | 1136 (58) | <0.001 |

| Anaemiab | 7 | 2577 (24) | 4523 (29) | 3285 (34) | 661 (36) | <0.001 |

| Valvular diseaseb | 0 | 1976 (17) | 3098 (19) | 2131 (21) | 398 (20) | <0.001 |

| Liver diseaseb | 0 | 169 (1) | 287 (2) | 263 (3) | 72 (4) | <0.001 |

| COPDb | 0 | 963 (8) | 1865 (11) | 1577 (15) | 338 (17) | <0.001 |

| Malignant cancer within 3 yearsb | 0 | 1347 (11) | 2059 (12) | 1357 (13) | 274 (14) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0 | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–4] | 3 [1–4] | 3 [1–5] | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| ACEi/ARB/ARNib | 1 | 10 936 (93) | 15 289 (92) | 9096 (89) | 1680 (86) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockerb | 0 | 10 678 (90) | 15 165 (91) | 9353 (91) | 1750 (90) | 0.148 |

| MRAb | 0 | 4544 (39) | 6691 (40) | 4249 (41) | 846 (43) | <0.001 |

| SGLT2id | 92 | 180 (20) | 279 (22) | 141 (18) | 34 (23) | 0.114 |

| Diureticb | 0 | 7487 (63) | 12 064 (72) | 8063 (78) | 1584 (81) | <0.001 |

| Nitrateb | 0 | 821 (7) | 1577 (9) | 1318 (13) | 243 (12) | <0.001 |

| Digoxinb | 0 | 1157 (10) | 1922 (12) | 1354 (13) | 271 (14) | <0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulantb | 0 | 5682 (48) | 8636 (52) | 5432 (53) | 993 (51) | <0.001 |

| Platelet inhibitorb | 0 | 4412 (37) | 6194 (37) | 3761 (37) | 719 (37) | 0.691 |

| Statinb | 0 | 6164 (52) | 8860 (53) | 5308 (52) | 975 (50) | 0.021 |

| Device therapyb | 1 | 0.155 | ||||

| No | 10 704 (91) | 15 121 (92) | 9343 (92) | 1759 (91) | ||

| CRT/ICD | 1008 (9) | 1396 (8) | 814 (8) | 183 (9) | ||

| Socioeconomic | ||||||

| Family typeb | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cohabitating | 7006 (59) | 9355 (56) | 5369 (52) | 985 (50) | ||

| Childrenb | 0 | 9961 (84) | 14 210 (85) | 8644 (84) | 1574 (80) | <0.001 |

| Educationb | 1 | <0.001 | ||||

| Compulsory/secondary school | 9019 (77) | 13 447 (81) | 8537 (84) | 1582 (82) | ||

| University | 2662 (23) | 3087 (19) | 1604 (16) | 340 (18) | ||

| Incomeb | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| <Median within a year | 4922 (42) | 8387 (50) | 5955 (58) | 1092 (56) | ||

| ≥Median within a year | 6895 (58) | 8314 (50) | 4339 (42) | 860 (44) | ||

- Abbrevations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNi, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EQ 5D-vas, Euro-QoL 5-dimensional visual analogue scale; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineral receptor antagonists; n, number; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors.

- a Included in the CRF 1 February 2008.

- b Included in multiple imputation and regression models.

- c Included in the CRF 2006.

- d Included in the CRF 28 April 2021.

Independent associations between baseline characteristics and the EQ 5D-vas categories ‘best’, ‘good’, ‘bad’ and ‘worst’ were evaluated by using a multivariable multinominal regression including the variables indicated in Table 1. The variables were selected based on clinical relevance. Possible outliers were evaluated using Cook's distance, and multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor without any cause for action.

Cox proportional hazards regressions were used to model the time to first event where death from other causes than the event itself were censored rather than treated as a competing event. Censoring was also performed at 12 months follow-up, in the case of migration from Sweden, or end of follow-up 31 December 2021. For the adjusted analyses, all baseline variables indicated in Table 1 were added to the model. The variables were selected based on clinical relevance. Separate analyses were further performed for the respective EF groups and for inpatient and outpatients. As a consistency analysis, the Fine and Gray subdistributional hazards model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was performed, where deaths not defined as an event were not censored but instead treated as a competing event.

All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1. The level of significance was set to 5%, two-sided. The R codes for all data handling and statistical analyses are found online (https://github.com/KIHeartFailure/swedehf-qol).

Results

Overall patient characteristics

Out of 207 290 registrations in SwedeHF between January 2000 and December 2021, a total of 40 809 patients fulfilled the selection criteria and therefore were included in the analyses (Table S1). Of those, 17% had HFpEF, 24% HFmrEF and 59% HFrEF. Among the included patients, 29% were in the ‘best’, 41% in the ‘good’, 25% in the ‘bad’ and 5% in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas categories. Median age (IQR) was 74 (65–80), and 32% were females.

Baseline characteristics of the overall population stratified by the EQ 5D-vas categories are shown in Table 1. Patients with ‘bad’ and ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas scores compared with those with ‘good’ or ‘best’ were older, more often female, had higher body mass index (BMI), higher NYHA class, had longer HF duration, had more CV and non-CV comorbidities, were more likely enrolled in the hospital setting, were less likely prescribed renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), were more likely to live alone, having no children, lower educational and income levels and reported a higher degree of symptoms including fatigue, shortness of breath, reduced mobility, incapability to maintain hygiene and main activities, more severe pain and anxiety/depression.

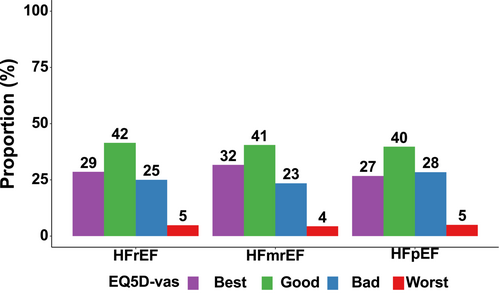

The distribution of EQ 5D-vas categories by EF category

Patients with HFpEF were more often in the ‘bad’ EQ 5D-vas category compared with those with HFrEF and HFmrEF (28% in HFpEF, 25% in HFrEF and 23% in HFmrEF) (Figure 1). Conversely, patients with HFmrEF were more frequently in the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category (32%) compared with HFrEF (29%) and HFpEF (27%). Similar proportions of patients with HFrEF (5%), HFmrEF (4%) and HFpEF (5%) were in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category. Differences in baseline patient characteristics according to EQ 5D-vas categories were consistent across HFpEF, HFmrEF and HFrEF (Table S3A–C).

Patient characteristics by EQ 5D-vas categories among inpatients and outpatients

Inpatients as compared with outpatients were more likely to suffer from other comorbidities regardless of EQ 5D-vas category (Table S4A,B). The distribution of the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category was similar among inpatients (28%) and outpatients (29%), whereas more inpatients (8% versus 4%) were in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category. Compared with inpatients, outpatients less often reported symptoms of fatigue, pain, anxiety/depression and inability to maintain main activities, even in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category. Among outpatients, patients with HFmrEF were more often in the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category as compared with HFrEF and HFpEF.

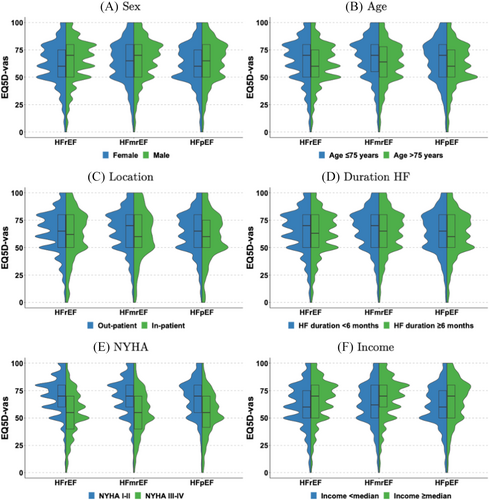

EQ 5D-vas scores by EF categories and patient characteristics

Median baseline EQ 5D-vas scores were overall slightly lower in HFpEF and HFrEF patients as compared with HFmrEF, among women, patients >75 years old and patients with longer HF duration, while EQ 5D-vas median scores were overall similarly distributed across the EF categories for inpatients, NYHA class and income level (Figure 2). The differences in EQ 5D-vas scores with regard to age and sex were greater in HFrEF, while the difference in EQ 5D-vas scores with regard to inpatient or outpatient setting was greater in HFmrEF.

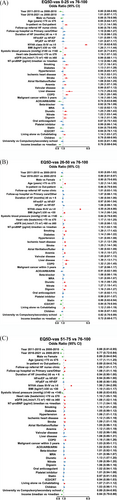

When analysing independent associations between patient characteristics and baseline EQ 5D-vas categories, NYHA class III–IV versus I–II was the strongest independent predictor of lower EQ 5D-vas [OR 7.51 (95% CI 6.62–8.52) for ‘worst’ vs. ‘best’, OR 4.55 (95% CI 4.26–4.86) for ‘bad’ vs. ‘best’ and OR 1.96 (95% CI 1.84–2.09) for ‘good’ vs. ‘best’], followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), smoking, higher BMI, higher heart rate, anaemia, previous stroke, ischaemic heart disease, use of diuretics and living alone. Higher income, male sex and higher systolic blood pressure were inversely associated with lower EQ 5D-vas (Figure 3). Being an inpatient was associated with the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category. Having children was inversely associated with the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category but not differentially with the other EQ 5D-vas categories. Liver disease was associated with the ‘bad’ and the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas categories. Older age (>75 years) and university level education were associated with the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ but not the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas categories.

EQ 5D-vas categories and clinical outcomes

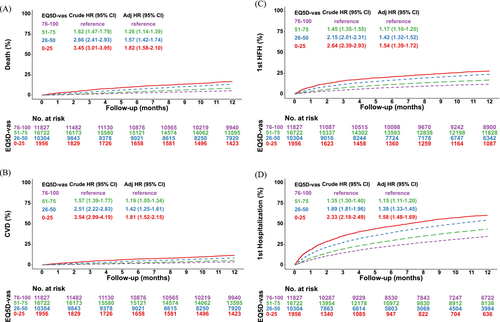

Figures 4 and S1–S2 and Tables 2, S5 and S6 present results on four outcomes up to 12 months follow-up for a total of 439 901 patient-years according to EQ 5D-vas categories for the overall population, stratified by all the three EF categories as well as separately for inpatient and outpatients. In adjusted analysis, the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category had the highest risk of all-cause death [HR 1.97 (95% CI 1.64–2.37) for HFrEF, HR 1.77 (95% CI 1.30–2.40) for HFmrEF and HR 1.43 (95% CI 1.02–2.00) in HFpEF]. The risk of all-cause death was greater for the lower EQ 5D-vas categories among inpatients as compared with outpatients. Patients in the ‘bad’ and ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas categories were at increased risk of CV death regardless of EF category, and inpatients were at greater risk than outpatients. The risks of first HF and all-cause hospitalizations increased in a stepwise manner among the lower EQ 5D-vas categories, regardless of EF categories. The increased risks of first HF and all-cause hospitalizations were more pronounced in inpatients as compared with outpatients. In a consistency analysis for the secondary outcomes, in which deaths not defined as an event were treated as a competing event, the results were consistent (Table 2).

| Outcome | Model | EQ 5D-vas 76–100 | EQ 5D-vas 51–75 | EQ 5D-vas 26–50 | EQ 5D-vas 0–25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death | Incidence/100py (95% CI) | 5 (5–6) | 9 (8–9) | 15 (14–15) | 19 (17–21) |

| Crude hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.62 (1.47–1.79), <0.001 | 2.66 (2.41–2.93), <0.001 | 3.45 (3.01–3.95), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.26 (1.14–1.39), <0.001 | 1.57 (1.42–1.74), <0.001 | 1.82 (1.58–2.10), <0.001 | |

| CV death | Incidence/100py (95% CI) | 4 (3–4) | 6 (5–6) | 9 (8–9) | 12 (11–14) |

| Crude hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.57 (1.39–1.77), <0.001 | 2.51 (2.22–2.83), <0.001 | 3.54 (2.99–4.19), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.19 (1.05–1.34), 0.006 | 1.42 (1.25–1.61), <0.001 | 1.81 (1.52–2.15), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted subdistributional hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.18 (1.04–1.34), 0.008 | 1.40 (1.23–1.59), <0.001 | 1.74 (1.46–2.08), <0.001 | |

| First HF hospitalization | Incidence/100py (95% CI) | 13 (12–14) | 19 (18–20) | 29 (28–30) | 36 (33–39) |

| Crude hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.45 (1.35–1.55), <0.001 | 2.15 (2.01–2.31), <0.001 | 2.64 (2.39–2.93), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.17 (1.10–1.25), <0.001 | 1.42 (1.32–1.52), <0.001 | 1.54 (1.39–1.72), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted subdistributional hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.17 (1.09–1.25), <0.001 | 1.38 (1.28–1.48), <0.001 | 1.46 (1.30–1.63), <0.001 | |

| First all-cause hospitalization | Incidence/100py (95% CI) | 45 (43–46) | 61 (60–62) | 87 (85–89) | 110 (103–116) |

| Crude hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.35 (1.30–1.40), <0.001 | 1.89 (1.81–1.96), <0.001 | 2.33 (2.18–2.49), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.15 (1.11–1.20), <0.001 | 1.39 (1.33–1.45), <0.001 | 1.58 (1.48–1.69), <0.001 | |

| Adjusted subdistributional hazard ratio (95% CI), P value | Reference | 1.16 (1.11–1.20), <0.001 | 1.37 (1.31–1.43), <0.001 | 1.51 (1.40–1.63), <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; EQ 5D-vas, EuroQoL 5-dimensional visual analogue scale; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; py, patient year; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Discussion

There were several important findings in the present analysis from the nationwide SwedeHF registry in which patient characteristics and clinical outcomes associated with HRQoL in patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF were examined1: among the included patients, most patients were in the ‘good’ or ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas categories.2 The distribution of the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category was similar among inpatients and outpatients.3 Median baseline EQ 5D-vas scores were overall slightly lower among HFpEF and HFrEF patients as compared with HFmrEF across several subpopulations.4 Higher NYHA class was most strongly associated with lower EQ 5D-vas while higher income and male sex had inverse associations with lower EQ 5D-vas.5 The 1 year risks of all assessed outcomes increased in a stepwise manner among the lower EQ 5D-vas categories, regardless of EF categories.

Most previous studies of HRQoL in HF have included only patients with HFrEF, are limited by small samples and lack in-depth analysis of clinical correlates and prognostic impact of HRQoL across all the EF categories and patient characteristics. In addition, previous studies have mainly assessed HRQoL with disease specific questionnaires such as the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) (evaluating 21 items) and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) (evaluating 23 items).7, 20, 21 However, these questionnaires are more time-consuming and costly than the EQ 5D-vas.22 In recent years, there has been a shift towards using single-item ‘global’ questions to assess HRQoL to improve its implementation in clinical care, although in clinical trials and for regulatory considerations, the KCCQ is the gold standard. The EQ 5D-vas, as employed in the present study, records the patient's self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale. The instrument can be applied across a diverse patient population minimizing language, cultural and socioeconomic barriers and thereby enhancing the reliability of patient-reported outcomes.

In the present study, the four HRQoL categories were distributed similarly to NYHA class, that is, with a vast majority in the middle two categories, and slightly more in the good than the bad category (analogously to more NYHA II than III) (Figure 2E). These findings are in line with a small previous study, where the median EQ 5D-vas scores were 70 (50–80) in patients with HFrEF (n = 169) and 70 (55–80) in patients with HFpEF (n = 191).23 Surprisingly, in our study, outpatients and inpatients reported being in the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category to a similar extent (29% vs. 28%, respectively). This suggests that a subset of inpatients may experience significant improvement and develop a positive outlook by the time of discharge. These findings are in line with the results of the REPORT-HF study, which demonstrated that nearly one-third of patients hospitalized with acute HF were classified as ‘alive and well’ (i.e., alive with excellent health status, defined by a KCCQ overall summary score >75) 6 months post-discharge.24 Furthermore, this positive health status generally persisted for at least 12 months. Symptoms of fatigue, pain, anxiety/depression and inability to maintain main activities were more frequently reported among the lower EQ 5D-vas categories and especially among inpatients. However, a surprisingly large proportion of the outpatients did not report any of these symptoms and not even in the ‘worst’ EQ 5D-vas category. It is possible that if HRQoL among these patients had been assessed using disease-specific questionnaires focusing on HF-related symptoms, they would have not been classified as having the ‘worst’ HRQoL.

Overall, patient characteristics differed in a similar way according to EQ 5D-vas categories in HFpEF, HFmrEF and HFrEF. Patients with HFpEF were older, had more comorbidities and reported more often ‘bad’ HRQoL. In the Global Congestive Heart Failure (G-CHF) study, including 23 291 patients from 40 countries, mean KCCQ-12 SS was comparable in patients with EF ≥ 40% and EF < 40%.25 Similarly, in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB Global Outcomes in HFpEF (PARAGON-HF) trial, patients with HFpEF (EF ≥ 40%) as compared with patients with HFrEF (EF < 40%) had similar HRQoL as assessed by the KCCQ-OS questionnaire.26 It is possible that merging HFpEF and HFmrEF into one group as in the G-CHF and the PARAGON-HF can explain these differences.

Few studies have performed a comparison of HRQoL across all the EF categories including HFmrEF. Thus, the present data add important information, given that HFmrEF appears to pathophysiologically more resemble HFrEF but in terms of severity, risk of outcomes and inclusion in clinical trials ‘belongs’ more to HFpEF.9 In a recent study reporting on change of HRQoL among the SwedeHF population, patients with HFmrEF were more often in the ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas category.27 Our findings add to this study by showing that the difference in EQ 5D-vas scores with regard to inpatient or outpatient setting was greater in HFmrEF. In addition, median baseline EQ 5D-vas scores were slightly lower among HFpEF and HFrEF patients as compared with HFmrEF, among women, patients >75 year and patients with longer HF duration while EQ 5D-vas median scores were similarly distributed among the EF categories for inpatients, NYHA class and income level. The differences in EQ 5D-vas median scores between men and women and patients >75 years were greater in HFrEF. When analysing independent associations between patient characteristics and baseline EQ 5D-vas categories, higher NYHA class was the strongest independent predictor of all lower EQ 5D-vas categories (the lower the EQ 5D-vas category, the higher OR) followed by HF-related comorbidities while male sex and sociodemographic factors such as higher income, higher educational level, having children were predictors of better HRQoL, consistent with findings of previous studies.25 Several mechanisms may underlie the impact of income disparity on HRQoL and prognosis in HF. In a study including 633 098 hospitalized HF patients in Taiwan, low-income patients had nearly a twofold increased risk of in-hospital mortality and adverse post-discharge events compared with high-income patients.28 This disparity was partly attributed to lower utilization of guideline-directed medical therapy among low-income groups. Additionally, intermediary factors such as poorly controlled blood pressure and associated behavioural risk factors, including smoking and physical inactivity, may further exacerbate outcomes in these patients.29

The EQ 5D-vas is designed so that patients are asked to mark a point on the scale that reflects their current overall health, considering all aspects of their physical and mental well-being. It is therefore interesting that NYHA class, specifically evaluating signs and symptoms of HF, is closely associated with worse EQ 5D-vas. Noncongestive conditions such as COPD, ischaemic heart disease and stroke were also observed to significantly influence HRQL, a finding that is consistent with prior studies of chronic HF.25, 26, 30 Female sex has repeatedly proven to be associated with worse reported HRQoL in HF populations, in other chronic conditions and in the general community.25, 26, 30, 31 It has been speculated that these differences may be related to increased prevalence of depression and decreased social support among women.32

In the present study, several outcomes were assessed at 12 months of follow-up including CV death, all-cause death or first HF or all-cause hospitalizations. Interestingly, the risks of all outcomes increased in a stepwise manner with worse EQ 5D-vas categories, regardless of EF categories and these risks were greater among inpatients. These findings, from a contemporary HF population seen in everyday clinical practice, are supported by the pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials in which the EQ-5D VAS scores were similarly associated with hospitalizations for HF and mortality.33 The EQ 5D-vas, although it is not a disease-specific instrument, demonstrates a high sensitivity for identifying HF patients at risk of worse outcomes.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, SwedeHF has incomplete coverage, with most patients enrolled in secondary rather than in primary care.14 The cohort size and generalizability is however considerably larger than other HF registries, and unlike epidemiological studies, it contains detailed HF-related parameters including continuous variables such as vital signs and biomarkers. Second, a substantial proportion of the SwedeHF population was excluded due to missing EF or EQ 5D-vas assessment, which may also contribute to selection bias. However, our findings are from a contemporary real-world register of patients with HF from hospitals as well as primary care centres covering the range of HF patients often excluded from clinical trials. Third, EF in the SwedeHF registry is assessed from echocardiograms performed in the context of routine clinical practice and not at an echocardiographic core laboratory. Fourth, in SwedeHF, the EF categories are defined according to the cut-off values from ESC HF Guidelines of 2016.15 According to the 2021 ESC classification of HF,34 patients with EF 40% would have been categorized as HFrEF and not HFmrEF as in the present study. However, as patients were included until 2021, all patients have been treated according to the previous ESC HF guidelines from 2016. Finally, there was no central event adjudication committee.

Conclusions

Most patients were in the ‘good’ EQ 5D-vas category, regardless of EF category. Higher NYHA class was most strongly associated with lower EQ-5D categories while higher income had the strongest inverse association with lower EQ 5D-vas categories across all EF categories. Lower EQ 5D-vas scores were associated with worse prognosis.

Clinical perspectives

Competency in medical knowledge: In this large contemporary and real-world cohort of patients with HF, most patients were in the ‘good’ and ‘best’ EQ 5D-vas categories, regardless of EF category. NYHA class was most strongly associated with lower EQ-5D-vas categories while higher income had the strongest inverse association across all EF categories. The 12 months risks of CV death, all-cause death, HF or all-cause hospitalizations increased in a stepwise manner with lower EQ 5D-vas categories. Inpatients had lower EQ 5D-vas scores across all EF categories and worse outcomes than outpatients.

Translational outlook: Patients with higher NYHA class and inpatients had worse HRQoL suggesting that improving signs and symptoms of congestion in HF may have a big impact on HRQoL across all EF categories. Addressing socioeconomic disparities in HF remain an important target for improving health status. There was a stepwise increase in the risks of CV and non-CV outcomes with lower EQ 5D-vas categories, supporting the use of the EQ 5D-vas as a feasible tool for assessing health status in HF.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff members at all care units in Sweden for their contribution to the SwedeHF Register.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Conflict of interest statement

C. Settergren: speaker's honoraria from Bayer and AstraZeneca, all outside the present work. L Benson: none declared. U. Dahlström: grants from Pfizer, Vifor, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche Diagnostics and honoraria/consultancies from Amgen, Pfizer and AstraZeneca, all outside the present work. T. Thorvaldsen: speaker's honoraria Boehringer Ingelheim, Orion Pharma and Abbot, all outside the present work. G. Savarese: grants and personal fees from Vifor, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Servier, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Cytokinetics, personal fees from Medtronic, grants from Boston Scientific, grants and personal fees from Pharmacosmos, grants from Merck, personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from TEVA, personal fees from Hikma, personal fees from GETZ, personal fees from Edwards LifeScience, personal fees from INTAS, outside the submitted work. L. H. Lund: is supported by Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Research Council (grant 523-2014-2336), the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation (grants 20150557 and 20190310) and the Stockholm County Council (grants 20170112 and 20190525) and reports unrelated to the present work; grants: AstraZeneca, Vifor, Boston Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and MSD; consulting: Vifor, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Pharmacosmos, MSD, MedScape, Sanofi, Lexicon, Myokardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Servier, Edwards Life Sciences and Alleviant; speaker's honoraria: Abbott, OrionPharma, MedScape, Radcliffe, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer; patent: AnaCardio; stock ownership: AnaCardio. B. Shahim: supported by Stockholm County Council (FoUI-969615), the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation (grants 20220524 and 20190322) and the Swedish Research Council (grant 2022-01472).