IgG4-related constrictive pericarditis with previous asbestos exposure: A case report and literature review

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis (CP) is characterized by impaired diastolic filling due to a thickened and fibrotic pericardium following trauma, inflammation, radiation or cardiac surgery. IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a multiorgan fibroinflammatory disorder that mimics many malignant, infectious and inflammatory diseases. IgG4-related CP is a rare manifestation of IgG4-RD that is known to cause pericardial fibrosis.1

Although the pathophysiology of IgG4-RD is unclear, it is thought to be involved in a mechanism of allergen tolerance. Chronic or repeated exposure to allergens may stimulate IgG4 formation and allergen binding by IgG4.2 A recent study reported that environmental exposures, particularly smoking and asbestos exposure, appear to play a role in the development of IgG-RD.3 Herein, we report a case of IgG4-related CP in a patient with a history of asbestos exposure who was successfully treated with surgical pericardiectomy and review the literature on IgG-RDs associated with asbestos exposure.4-11

Case report

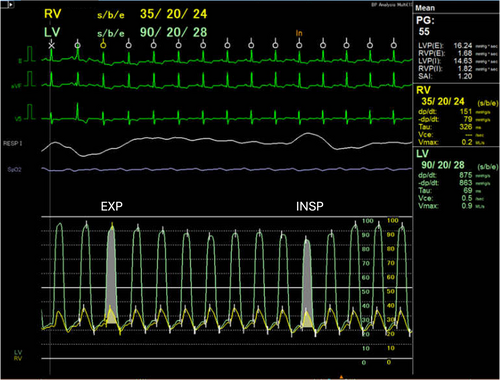

A 72-year-old man with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia presented with a two-week history of dyspnea and severe oedema. He was a civil engineer and had a history of asbestos exposure for 20 years (until age 40). At the time of presentation, he was a smoker, having smoked 15 cigarettes per day for 52 years. He had no known allergies and his family history was unremarkable. On arrival, his vital signs were as follows: body temperature of 36.5°C, blood pressure of 110/72 mmHg, heart rate of 98 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute and saturation of 93% on room air. Physical examination revealed Kussmaul's sign, rales at the base of both lungs and pitting oedema in both lower extremities. Electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm and a low voltage throughout the limb leads. Chest radiograph showed pleural effusion and calcified shadows in both lung fields (Figure 1). Laboratory tests revealed elevated levels of C-reactive protein (2.54 mg/dL; normal range < 0.14 mg/dL), serum creatinine (1.21 mg/dL; normal range 0.46–0.79 mg/dL) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (560 pg/mL; normal range < 125 pg/mL). Chest computed tomography (CT) scans showed bilateral pleural plaques and effusion, as well as thickened pericardium (pericardial thickness was a maximum of 11 mm at the apex) and pericardial effusion (Figure 1). Transthoracic echocardiography showed preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, septal bounce and pericardial thickening with effusion at the apex (Figure 2). The medial e′ velocity (9.5 cm/s) was greater than the lateral left ventricular e′ velocity (7.8 cm/s), and the mitral inflow and tricuspid valve velocity varied with respiration (Figure 2). The inferior vena cava was dilated without respiratory changes, indicating increased right atrial pressure.

After initiation of diuretics for symptom relief and an 8 kg of weight loss with the treatment, the patient underwent further diagnostic testing. Coronary angiography showed significant stenosis of the left anterior descending artery. Right heart catheterization revealed elevated levels of bilateral cardiac pressures, including pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (24 mmHg), left ventricular diastolic pressure (28 mmHg), right ventricular diastolic pressure (24 mmHg), and right atrial pressure (21 mmHg), and the systolic area index was 1.20 (Figure 3). Based on these findings, a definitive diagnosis of CP with coronary artery disease was made.

Additional laboratory tests were performed to evaluate the possibility of an undiagnosed malignancy or autoimmune disease associated with CP. Results of autoantibody testing were negative, and no apparent elevations of lung tumour markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, cytokeratin fragment, pro-gastrin releasing peptide, squamous cell carcinoma antigen and soluble mesothelin-related peptide, were noted. However, the serum IgG and IgG4 levels were 1939 and 1190 mg/dL, respectively (normal range: 861–1747 and 11–121 mg/dL). Therefore, IgG4-RD with pericardial involvement was suspected.

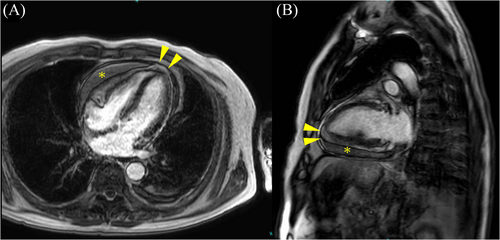

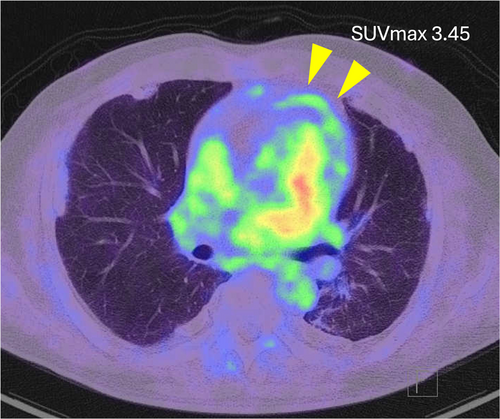

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse thickening of the pericardium with moderate pericardial effusion and increased delayed pericardial enhancement (Figure 4). The patient also underwent an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT scan, which showed uptakes of 18F-FDG in the pericardium, consistent with isolated pericardial involvement of IgG4-RD (Figure 5). The semiquantitative measurement of 18F-FDG uptake and the maximum standardized uptake value of the pericardium was 3.45, indicating active pericardial inflammation. No uptake was detected in non-pericardial tissues, including pleural plaques, and there was no evidence of malignancy or inflammation other than the pericardium. Also, the patient had no organ manifestations of IgG4-RD other than the pericardium.

The initial treatment with diuretics only worsened his creatinine level without much improvement in his symptoms and resolution of the pleural effusion; in addition, coronary intervention was required. We therefore proceeded with surgery and the patient underwent total pericardiectomy with regional waffle procedure and coronary artery bypass grafting.

After median sternotomy, circumferential pericardial thickening and adhesions with pockets of pericardial fluid around the heart were observed (Figure 6). The pericardial fluid contained elevated levels of IgG4 (481 mg/dL). Histopathological examination of the pericardial specimen revealed a thickened fibrocollagenous pericardium with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (Figure 7). Immunohistochemistry revealed >10 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high-power field with an IgG4/IgG ratio of >40% (Figure 7). Neither classic storiform fibrosis nor mild tissue eosinophilia was present. Based on the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for IgG4-RD, the diagnosis of IgG4-related CP was confirmed.12 After surgery, the patient's symptoms and laboratory values improved significantly (serum creatinine of 0.80 mg/dL and IgG4 of 414 mg/dL). The postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged home on postoperative day 9. The follow-up echocardiogram 1 month after surgery showed the disappearance of CP findings such as septal bounce, pericardial thickening and significant mitral/tricuspid inflow variations. The patient was treated with furosemide, spironolactone and dapagliflozin and had no recurrence of heart failure 5 months after surgery.

Discussion

IgG4-RD is an autoimmune disease characterized by tissue IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration.13 Although cardiovascular IgG4-RD has been reported, IgG4-related CP is under-recognized and its diagnosis is often challenging.14 Regarding the pathogenesis of IgG4-RD, a recent review reported that tobacco and asbestos exposure can trigger IgG4-RD.3 Table 1 lists the previous cases of IgG4-RD associated with smoking and asbestos exposure.4-11 Consistent with previous reports, the present case, which we diagnosed as IgG4-related CP, was a smoker and had a history of asbestos exposure.

| No | Author [reference] | Age (years) | Sex | Smoking | Asbestos exposure | Duration of asbestos exposure (years) | Latency period from last asbestos exposure (years) | Asbestos-related pleural lesions | Affected organ of IgG4-RD | Serum IgG4 (mg/dL) | Therapy | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sato4 | 72 | M | ND | Yes | ND | ND | Yes | Retroperitoneal lymph nodes | 453 | ND | ND |

| 2 | Toyoshima5 | 57 | M | Yes (30 cigarettes per day/30 years) | Yes | 10 | ND | Yes | Lung | 3520 | Fluticasone propionate (500 μg) and salmeterol xinafoate (50 μg) twice daily | Alive (2 years) |

| 3 | Kamiya6 | 65 | M | Yes (30 cigarettes per day/15 years) | Yes | 5 | ND | No | Retroperitoneum | 213 | Prednisolone 60 mg/day | Alive (6 months) |

| 4 | Onishi7 | 67 | M | Yes (20 cigarettes per day/15 years) | Yes | 42 | 5 | Yes | Submandibular glands and lung | 1430 | Prednisolone 40 mg/day | Alive |

| 5 | Gayewska8 | 58 | M | Yes (2 pack-years) | Yes | ND | 20 | Yes | Pleura | 141 | Prednisolone 37.5 mg/day → prednisolone 7.5 mg/day + azathioprine 50 mg bid → prednisolone 7.5 mg/day +methotrexate 15 mg weekly | Alive (1 year) |

| 6 | Lococo9 | 65 | M | Yes | Yes | ND | ND | Yes | Pleura | 253 | Prednisolone 50 mg/day | Alive |

| 7 | Torres10 | 78 | M | ND | Yes | 13 | 28 | Yes | Pleura, retroperitoneum and retrosternum | 592 | ND | ND |

| 8 | Ono11 | 71 | M | Yes (20 pack-years) | Yes | ND | ND | Yes | Left diaphragm | ND | Left lower lobectomy and resection and reconstruction of left diaphragm | Alive |

| 9 | Present case | 72 | M | Yes (15 cigarettes per day/52 years) | Yes | 20 | 32 | Yes | Pericardium | 1190 | Pericardiectomy | Alive |

- Abbreviations: M, male; ND, not described.

A review of the cases listed in Table 1 showed that the mean age at presentation was 67 years (range: 58–78 years). Of note, all patients were male and above middle age, both of which are consistent with previous population-based reports15 showing that most (62%–83%) IgG4-RD patients are male and older than 50 years, a finding that suggests a possible relationship with the male predominance of occupational asbestos exposure. Seven of the nine patients had a history of smoking. The duration of asbestos exposure ranged from 5 to 42 years. The latency period between the last exposure to asbestos and the onset of the disease was more than 20 years in three cases and 5 years in one case, who had the longest exposure of 42 years. Asbestos-related pleural lesions were observed in almost all cases. Affected sites of IgG4-RD may include the pleura, retroperitoneum, lung, submandibular glands, retrosternum, diaphragm and pericardium, as in the present case. The reported mean serum IgG-4 level was 974 mg/dL (range: 141–3520 mg/dL). Regarding treatment, four cases were treated with prednisolone or immunosuppressants, two cases underwent surgical resection, and one patient was treated conservatively. All cases for which clinical outcomes were available remained alive during follow-up.

In general, the treatment of IgG4-RD is pharmacological therapy with glucocorticoids as first-line agents; alternatives may include immunosuppressive drugs (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, leflunomide, tacrolimus, cyclosporin A, iguratimod and cyclophosphamide) and biological agents such as rituximab.13 However, the treatment of IgG4-related CP is controversial as to whether steroid treatment or surgery should be prioritized. A previous review reported that most cases of IgG4-related pericarditis responded well to initial treatment with pericardiectomy and/or glucocorticoids.16 In our case, the benefits and risks of steroid treatment versus surgery were extensively discussed on a multidisciplinary basis. It was agreed that if steroid treatment is chosen, the patient must first undergo a pericardial biopsy for a clearer histopathological diagnosis. In addition, the patient must also undergo percutaneous coronary intervention and dual antiplatelet therapy to treat the coronary disease. Furthermore, if the steroid treatment fails and the patient ultimately requires surgery, the subsequent surgical treatment would likely be compromised by the risk of infection and bleeding enhanced by the pharmacological therapy. Therefore, the decision was made to proceed with surgery first in this patient.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of IgG4-related CP associated with a previous asbestos exposure that was successfully treated with surgical pericardiectomy. Physicians should be aware that asbestos exposure may be a possible cause of IgG4-RDs including IgG4-related CP, even if the latency period from the last asbestos exposure is more than 20 years.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.