Reading acquisition among students in Grades 1–3 with intellectual disabilities in Sweden

Abstract

This study investigates the reading performance of younger students with intellectual disabilities to gain insight into their needs in reading education. Participants were 428 students in Grades 1 to 3 in Sweden. They performed LegiLexi tests measuring pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension based on the model of Simple View of Reading. Results demonstrate a great variation in reading acquisition among students. Some students are able to decode single words and read shorter texts with comprehension already in Grade 1. Other students still struggle with learning letters and developing phonological awareness in Grade 3. According to their longitudinal data over grades, results show that most students progress in pre-reading skills, decoding, and reading comprehension. Hence, assessing reading skills among students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1–3 using tools aligned with the Simple View of Reading seems applicable and informative for teachers. This study underscores the significance of informed instructional practices for empowering these students in reading education.

1 INTRODUCTION

Reading is crucial for success in all academic domains, daily living activities and social interactions. However, some students encounter difficulties in acquiring functional reading, particularly those with intellectual disabilities. These students have deficits in cognitive capacity, which usually impact reading negatively (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, students with intellectual disabilities constitute a highly heterogeneous group of learners (Maulik et al., 2011). However, many face substantial challenges in learning to read single words and read text with comprehension (Lemons et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2011). To our knowledge, the students' reading proficiency has yet to be comprehensively assessed in Sweden. Therefore, in the present study, we contribute insights into the performance of students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1–3 in pre-reading, decoding and reading comprehension.

Prior to word decoding, students need to develop pre-reading skills, which serve as a bridge between spoken and written language, enabling students to transition from oral language comprehension to reading comprehension (Castles et al., 2018; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012). With a solid foundation in pre-reading skills, students may avoid considerable challenges in acquiring word decoding and reading comprehension. Pre-reading skills include phonemic and phonological awareness, which refers to the ability to distinguish and manipulate the auditory units of spoken language, and letter knowledge, which refers to recognising and naming letters of the alphabet (Hogan et al., 2005). By acquiring letter knowledge, students can connect letters to their corresponding sounds and utilise this knowledge to decode words (Ehri, 2005). Similarly to peers without intellectual disabilities, both letter knowledge and phonological awareness are reported as essential in the reading development of students with intellectual disabilities (cf., Alnahdi, 2015; Browder et al., 2009). Among students with intellectual disabilities, research has demonstrated that those with higher levels of letter knowledge tend to have better reading (Alnahdi, 2015), and effective letter knowledge instruction is reported to enhance their word decoding (Afacan, 2020; Alquraini & Rao, 2020; Browder et al., 2006). Likewise, instruction in phonological awareness can improve reading in students with intellectual disabilities.

Comprehensive research has demonstrated that students with intellectual disabilities encounter more significant challenges in developing word decoding than their typically developing peers (for meta-analyses, see Dessemontet et al., 2019; Gilmour et al., 2019). However, there is considerable variability in the word decoding abilities among students with intellectual disabilities (Allor & Chard, 2011), but decoding skills are essential for reading comprehension (Ehri, 2014; Gough & Tunmer, 1986). Generally, research demonstrates that students with intellectual disabilities face challenges in reading comprehension (Alquraini & Rao, 2020; Lemons et al., 2013), potentially related to difficulties in decoding, understanding text structure and making inferences (Dessemontet et al., 2019; Gilmour et al., 2019).

1.1 Aim of the study

- How do students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1 to 3 perform on tests measuring pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension?

- How does performance in pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension develop over time among students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1 to 3?

2 METHODS

2.1 Context of the study

In Sweden, students with intellectual disabilities can either attend mainstream schools alongside their peers without disabilities or enrol in specialised schools referred to as Compulsory school for pupils with intellectual disabilities (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023). During the academic year 2022/2023, about one percent of the total student population in Sweden was enrolled in compulsory school for students with intellectual disabilities. These students attend compulsory education for 10 years, commencing Grade 1 when they turn seven. Compulsory schools for pupils with intellectual disabilities in Sweden should offer high-quality education and support, focusing on meeting individual needs and promoting inclusion in society. Publicly funded, these schools provide a tailored educational programme considering each student's needs, abilities and goals.

The compulsory schools for students with intellectual disabilities in Sweden often feature smaller class sizes and a higher student-to-teacher ratio than regular schools, facilitating more individualised instruction and support. The students follow a curriculum distinct from their peers without an intellectual disability. The curriculum addresses the academic and social needs of students with disabilities, supporting their development in communication, social skills and independence. According to the curriculum, education for students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1 to 3 should focus on letter knowledge, decoding and strategies for comprehending words and student-oriented texts (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023).

2.2 Participants

In total, results from 428 unique students are included in this study, and 72 were tested in more than one grade, which means the study includes test results from 500 testing occasions. The distribution of students is as follows across the grade levels: Grade 1 = 103, Grade 2 = 182 and Grade 3 = 215. All participants were registered as students following the compulsory school curriculum for students with intellectual disabilities (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023) and were sourced from the LegiLexi database from 2019 to 2021. LegiLexi is a cost-free, non-profit digital platform for teachers that focuses on enhancing reading among Grades 1–3 in Swedish compulsory schools (www.legilexi.org). Its purpose is to provide teachers with reading tests and recommendations for individual and class instruction in reading education.

Swedish law (2003:460) states that research involving physical intervention, biological, genetic, biometric, or sensitive personal data requires ethical approval. Ethical approval was unnecessary since the LegiLexi data used in this study does not contain sensitive personal information and cannot be linked to any specific student, which the Swedish Ethical Review Authority has confirmed.

2.3 Instruments

In the current study, all test results come from LegiLexi's database, accessible via www.LegiLexi.org. Swedish reading experts construct and evaluate these tests, which are based on the theoretical model of the Simple View of Reading (for information about the model, see Gough & Tunmer, 1986). One key feature of LegiLexi is that it provides teachers with feedback on student progress and recommendations for further teaching. LegiLexi also provides a manual that teachers can follow.

2.3.1 Pre-reading

Two tests that measured the students' pre-reading were included: letter knowledge and phonological awareness.

Letter Knowledge: This test comprises 12 tasks. The student hears a letter sound while simultaneously viewing 10 different letters. The task is to choose the letter that corresponds to the given sound. In the first four tasks, the letters are uppercase; in the next four, they are lowercase; and in the final four tasks, there is a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters. The test assesses fricative consonants (f, l, m, n, r, s, v, l, j) and plosives (b, p, d, t, g, k). It also evaluates whether the student can distinguish between similar graphemes (b/p and f/t) and letters with similar sounds (y/i, b/d). If the student fails to pass the test, meaning they score less than 11 correct answers, the test will be retaken at the next testing session. However, if the student answers all questions correctly or has only one error, the test will be concluded, and the student will not be required to further assess their letter recognition skills in subsequent testing sessions. The test duration was approximately 5 min, and the reported test–retest correlation for Grade 1 was r = 0.58 (Fälth et al., 2017).

Phonological awareness: The test consists of four parts encompassing 26 tasks. The student hears a letter sound in the first three sections while viewing five pictures illustrating common everyday words. The task is to choose the picture corresponding to the letter sound at the beginning (6 tasks), end (6 tasks) or inside (6 tasks) of the word. Tasks progressively increase in difficulty from sound-consistent to sound-inconsistent words. In the final part, the student hears the phonemes in a word pronounced and is instructed to choose the picture representing the word created by these phonemes (8 tasks). The difficulty level of the words gradually increases from three up to a total of seven phonemes. The maximum score is 26, and the reported test–retest correlation for Grades 1–2 was r = 0.63–0.75 (Fälth et al., 2017). If the student has no more than one error in each of the four parts, the test will be concluded; otherwise, the test will be retaken at the next available testing session.

2.3.2 Decoding

The students' decoding was measured by two tests, measuring decoding of words and non-words.

Decoding words: This test is conducted individually by a teacher with a student. It involves a list of 144 words, and the student must read aloud as many as possible correctly within 1 min. The teacher monitors the time, notes any misreadings and records the number of correctly read words. The list is the same at every testing point, with words progressively increasing in length and difficulty, with a maximum score of 144. The reported test–retest correlation for Grades 1–3 was r = 0.87–0.88 (Fälth et al., 2017).

Decoding non-words: Similarly, a teacher administers this test individually. It comprises a list of 84 made-up words, and the student is tasked with correctly reading as many as possible within 1 min. The teacher tracks the time, records misreadings and notes the number of correctly read words. The words in this test also progressively increase in length and difficulty, with a maximum score of 84. The reported test–retest correlation for Grades 1–3 was r = 0.84–0.86 (Fälth et al., 2017).

2.3.3 Comprehension

Reading comprehension: This test comprises 12 tasks. Students read short texts about Sara and Leo, progressively increasing in difficulty, with the readability measure indicating (LIX) the difficulty of reading a text ranging from 3 to 18. Texts with LIX < 30 are categorised as easy to read, akin to children's books. Following each text, the student must select the most fitting image from five similar options that best represent the content of the text they have just read. The test is time-limited to 5 min, assessing the student's ability to find information (reading on the line) and draw conclusions (reading between the lines). The maximum score achievable is 12, and the reported test–retest correlation for Grade 1 was r = 0.75 (Fälth et al., 2017).

2.4 Analysis

Means, standard deviations, and percentages below the 25th percentile from primary school students without intellectual disabilities were calculated for each grade and test. The cut-off of the 25th percentile is usually applied to identify students with special needs in reading (see, for example, Al Otaiba et al., 2014).

For 52 students, where missingness of the tests, phonological awareness, and letter knowledge were likely due to passing a previous test occasion, the scores were imputed to 26 and 12, respectively, to avoid underestimating the general performance.

Longitudinal development was analysed with a paired sample t-test for students from several grades. Pearson correlations between phonological awareness, letter knowledge, reading comprehension, decoding words and non-words were calculated for each grade.

3 RESULTS

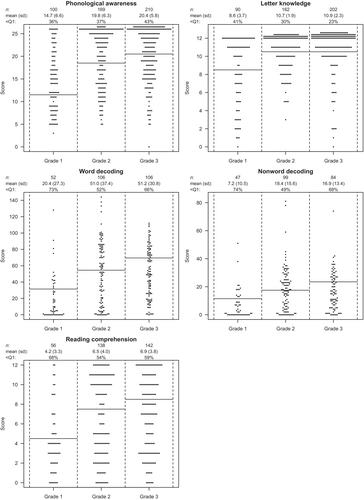

The LegiLexi tests were administered to students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1–3 to assess their pre-reading skills (letter knowledge and phonological awareness), decoding (reading words and non-words), and reading comprehension. According to the test results illustrated in Figure 1, there is a variation in the students' performance. Some students scored higher than the 25th percentile, indicating they can decode words and read shorter texts with comprehension already in Grade 1. This finding shows that some students progress well in reading acquisition. However, others received low scores and are still in Grade 3 and need education to learn letters and acquire phonological awareness to progress in reading. Subsequently, early reading education for students with intellectual disabilities must meet various skills and needs.

The strength of the associations between the tests measuring pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension was analysed with Pearson correlations, see Table 1. For students in all Grades, phonological awareness and letter knowledge had positive associations with decoding and reading comprehension. Medium to large effect sizes were demonstrated for the association between phonological awareness and decoding among students in Grades 1 and 2, while the association was weaker among students in Grade 3. The letter knowledge test showed the strongest association with decoding and reading comprehension among students in Grade 2, which could indicate that students in Grade 1 and 3 have weaker letter knowledge. Those in Grade 1 have less experience in reading education, whereas those who perform the letter knowledge test in Grade 3 struggle with pre-reading skills.

| Grade 1 n = 49–53 | Grade 2 n = 79–112 | Grade 3 n = 58–105 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Decoding words | Decoding non-sense words | Reading comprehension | Decoding words | Decoding non-sense words | Reading comprehension | Decoding words | Decoding non-sense words | Reading comprehension |

| Phonological awareness | 0.62*** | 0.55*** | 0.46*** | 0.63*** | 0.60*** | 0.64*** | 0.39** | 0.33* | 0.41*** |

| Letter knowledge | 0.43** | 0.39** | 0.20 | 0.52*** | 0.53*** | 0.49*** | 0.26* | 0.22 | 0.24* |

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.00.

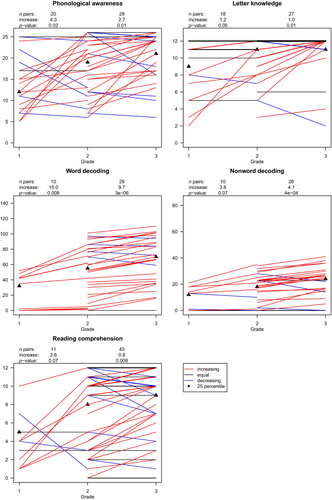

Figure 2 presents the students' pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension performance over time. The scores in different grades reveal the students' development over time. Figure 2 shows that most students have progressed in pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension. Nevertheless, some students have not developed in these tests, while others have even regressed.

4 DISCUSSION

Older students with intellectual disabilities are reported to struggle with reading (Dessemontet et al., 2019; Gilmour et al., 2019), but the reading ability among young students has not reached the same attention. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the reading performance of students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1 to 3 to gain insight into their needs in reading education. As students with intellectual disabilities show diverse linguistic and cognitive abilities (c.f., Maulik et al., 2011), our findings also demonstrated a heterogenous reading acquisition among the participating young students. For example, some students, such as seven-year-olds, are able to decode single words and read shorter texts with comprehension already in Grade 1. In contrast, others, such as nine-year-olds, struggle with learning letters and developing phonological awareness. Within and between grades, students differ greatly in pre-reading skills, decoding words and non-words, and reading shorter texts with comprehension. However, the results indicate that students develop over time, and adequate teaching should play a decisive role.

As students with intellectual disabilities have various abilities and needs in reading (cf. Afacan & Wilkerson, 2022), teachers must evaluate each student's pre-reading skills, decoding, and reading comprehension to plan meaningful lessons and teach students efficiently. Nevertheless, assessing reading acquisition among students with intellectual disabilities must be conducted with respect to each student's linguistic and cognitive abilities. Therefore, teachers must carefully choose tests and consider the aim of the assessment concerning students' abilities and reading education. First, the pre-reading skills must be assessed among the students, and those who have acquired letter knowledge and phonological awareness are ready for further assessments with tests measuring reading single words and short, easy texts (cf. Alquraini & Rao, 2020; Dessemontet et al., 2019). The test results should then form the basis for further planning and teaching of reading instructions.

However, there are no validated reading and writing tests for students with intellectual disabilities in Sweden. The lack of such tests has resulted in teachers using the LegiLexi tests among these students, and the current study is based on this use. Since the results showed various test performances, the LegiLexi tests seem to identify those struggling with pre-reading skills, decoding, and reading comprehension. Therefore, our findings suggest the usefulness of assessment tools for students with intellectual disabilities, such as LegiLexis, designed in accordance with the Simple View of Reading (for information about the model, see Gough & Tunmer, 1986). The LegiLexi tests were developed to be regularly applied three times a year in reading education, as regular reading assessment is crucial for informing instructional practices. Students with low performance need additional instructions tailored to their needs to progress in reading (Browder et al., 2009).

The longitudinal data in the current study showed that most students have progressed in pre-reading skills, decoding and reading comprehension. Notably, some students did not progress or regressed. These results indicate the importance of teachers monitoring each student's reading progress, and those students who are not progressing from one grade to another must be recognised and supported with individual instructions and digital technology.

A teacher who knows how far the student has come in reading development is better placed to provide relevant and meaningful reading instructions (see, e.g., Dessemontet et al., 2019). Some students might need support and tailored interventions, whereas others may need additional instructions to overcome more challenges in their reading than their peers (Ruppar, 2017). Teachers must not have too low expectations of their students, as their positive beliefs are related to students' reading progress (Cameron & Cook, 2013). When the students have acquired pre-reading skills, they need effective reading education focusing on word decoding, reading fluency, comprehension and vocabulary acquisition (Alquraini & Rao, 2020; Dessemontet et al., 2019). A comprehensive understanding of reading acquisition, including phonological awareness and letter-sound relationships, is imperative for effective instruction. Thorough evaluation of students' reading development ensures tailored instructional strategies, aligning appropriately with developmental stages. Gaining insights into students' reading proficiency and phonological awareness enables targeted interventions, fostering a supportive learning environment.

International research has evaluated reading education for students with intellectual disabilities (Alquraini & Rao, 2020). Generally, the students will progress with multicomponent individualised instructions. They also need teaching for a long time (Browder et al., 2006). Recent reading intervention studies in Swedish underscore the importance of systematic reading instruction for students with intellectual disabilities (Fälth et al., 2023; Samuelsson et al., 2024). In the single case study by Fälth et al., decoding skills were taught with the Wolff Intensive Programme (Wolff, 2015) supported phonemic decoding and reading fluency training during 25 sessions. The participating students with mild intellectual disabilities enhanced decoded words in a given time (NAP = 0.84–1.00) and reduced decoding errors (NAP = 0.72–1.00). In the study by Samuelsson et al., four pairs of teachers shared their perceptions of a 12-week intervention focusing on phonics and comprehension strategies by using two different apps for students with mild to severe intellectual disabilities. According to the teachers, the apps with stepwise instructions motivated the students in reading education and thereby also supported the students' reading acquisition.

4.1 Limitations

The current study is based on data from the LegiLexi database, and it included 428 students following the compulsory school curriculum for students with intellectual disabilities in Grades 1 to 3 from 2019 to 2021. Since personal information is not registered in the database, we cannot present more detailed information about the students. For example, the students' intellectual levels, diagnoses, first languages or other factors that could affect the generalisability are not accessible through the database. Although the study has a large sample, it might include some bias. Teachers using LegiLexi tests with students with intellectual disabilities might differ from other teachers educating students with such disabilities in Sweden. For instance, these teachers might have a specific interest and competence in reading education and, therefore, also promote reading acquisition among students with intellectual disabilities. Thus, the sample is large, which suggests that the results are representative of young students with intellectual disabilities in Sweden.

4.2 Conclusion

In conclusion, findings from the current study showed various reading acquisitions among students with intellectual disabilities. They have various abilities, progress, and needs in reading. Therefore, to meet this heterogeneous group of students, teachers must assess each student's pre-reading skills, decoding, and reading comprehension. The assessment results must be evaluated and form the basis for high-quality teaching, including didactic choices and adjustments in reading instructions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the LegiLexi Foundation for assisting us with anonymous data files.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study received funding from Swedish Institute for Educational Research (Dnr 2021–00049).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the authorship and publication of this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.