Epidemiology of biopsy-proven glomerular diseases in Chinese children: A scoping review

Edited by Yi Cui

Abstract

Background

Glomerular disease is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease globally. No scoping review reports have focused on China's spectrum of glomerular diseases in children. This study aimed to systematically identify and describe retrospective studies on pediatric glomerular disease based on available data on sex, age, study period, and region.

Methods

Six databases were systematically searched for relevant studies from initiation to December 2021 in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Global Health Library, Wangfang Database, and CNKI.

Results

Thirty-four studies were identified in the scoping review, including 40,430 patients with biopsy-proven diagnoses. The proportion of boys was significantly higher than that of girls. In this study, 28,280 (70%) cases were primary glomerular disease, 10,547 (26.1%) cases were diagnosed as secondary glomerular disease, and 1146 (2.8%) cases were hereditary glomerular disease. Minimal change disease is the most common glomerular disease among children in China, followed by mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, and purpura nephritis. We observed increments in glomerular diseases in periods 2 (2001–2010) and 3 (2011–2021). The proportion of major glomerular diseases varies significantly in the different regions of China.

Conclusion

The spectrum of pediatric glomerular diseases varied across sex, age groups, study periods, and regions, and has changed considerably over the past 30 years.

Highlights

-

The composition of pediatric glomerular disease in China has changed so much.

-

Few scoping review reports have focused on Chinese children with glomerular disease.

-

Unlike adults, minimal change disease was the most common glomerular disease in children.

-

Four age groups, three study periods, and four regions were included in the subgroup analysis of biopsy-proven pathological results.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been recognized as a health problem, and one of the leading causes of CKD globally and in China is glomerulonephritis. A study by Lancet showed that the number of patients has reached 132.3 million in China,1 which is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide. The increase in childhood CKD is threatening to reach epidemic proportions in the next decade. Compared with adults, a significant percentage of pediatric patients were diagnosed with congenital diseases and glomerulonephritis, rather than secondary glomerular disease. Similarly, the problem of CKD in children should not be underestimated, as reported in other countries.2-5

Glomerular disease is one of the leading causes of end-stage renal disease in adults and children.6-9 Moreover, children with glomerulonephritis may experience a progressive disease course of CKD compared to those with congenital disease.10, 11 The management and prognosis of glomerular disease may vary widely, depending on the different pathological diagnoses.12 However, few studies have been conducted on the spectrum of glomerular diseases in children compared to adults. Children are vulnerable groups who need and deserve protection. It is essential to investigate the composition of biopsy-proven glomerular disease in pediatric patients to provide more detailed information to the primary physician, regarding pathological variability across sex, age groups, time periods, and regions. A more accurate clinical diagnosis would be provided when children cannot undergo renal biopsy for various reasons.

Although some retrospective studies have provided information on Chinese children using renal biopsy, many studies have attributes that cannot explain the changes and statistical differences in children's pedigrees over the past 30 years. For example, several studies were excluded due to age <18 years or a small sample of data from inpatient children.13 Specifically, the spectrum of pediatric glomerular diseases is necessary for inquiry learning.

No scoping review reports have focused on the pediatric spectrum of glomerular diseases in China. Therefore, our study aimed to assess the evolving epidemiology of pediatric glomerular diseases in China. Specifically, we focused on summarizing the analysis of these retrospective studies and strategies used to improve the protection of pediatric patients as a vulnerable population.14

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

The goal of a scoping review is to identify quantitative or qualitative evidence, which is represented by mapping or charting the data, and summarizing the studies by time, region, and origin.15, 16 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews diagram was used to guide the review process.17 The method proposed by Arksey and O'Malley14 comprises five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

2.2 Identifying the research question

The following question was identified: What is known about the epidemiology of biopsy-proven glomerular diseases among children in China until 2021?

2.3 Identifying relevant studies

The following databases were systematically searched to identify relevant studies: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Global Health Library, Wangfang Database, and CNKI from initiation to December 2021. We combined the search terms “glomerular disease” OR “glomerulonephritis” OR “nephritis” OR “kidney patholog*” OR “renal patholog*” OR “kidney disease” OR “renal disease” OR “kidney biopsy” OR “renal biopsy” OR “GD” OR “KP” OR “RP” OR “KD” OR “RD” OR “KB” OR “RB” AND “child*” OR “adolescent*” OR “infant” OR “pediatric*” OR “pediatric patient.” The detailed search strategy is presented in Supporting Information: Table S1. The reference lists of the included studies and relevant reviews were manually searched to identify any remaining studies.

2.4 Study selection

First, researchers independently read the abstracts of relevant studies, performed key information extraction, and jointly developed a data extraction table to extract study characteristics. Subsequently, the full text was assessed by two reviewers to judge whether the study was relevant to the selection criteria. Additionally, a third party participated when the discrepancies were resolved.

Inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: (1) Chinese patients under 18 years of age; (2) studies were limited to English and Chinese languages; and (3) the sample size was >100. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Case reports, animal experiments, and commentaries; (2) studies without baseline data or original information; and (3) studies without enough quantitative data and the corresponding author cannot be contacted.

2.5 Charting the data

We collected the following information from each eligible study: the first author of the study, year of publication, sample size, region distribution, sex, age, pathological composition, and main findings. Pediatric patients were divided into four age groups: infants (<3 years), preschool (3–7 years), younger children (7–13 years), and adolescents (13–18 years). The three-period groups were defined as period 1 (studies before 2001), period 2 (studies between 2001 and 2010), and period 3 (studies between 2011 and 2021). Four region groups, including north, south, east and west, were defined based on the geographical division of China.

2.6 Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

First, we followed the workflow to search for and select studies. All data were summarized and charted as graphs, and the extracted data were analyzed using descriptive statistics according to the characteristics of the studies. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 25.0; SPSS Inc.). The Wilcoxon test and t-test were used to compare continuous variables. Categorical data are presented as frequency (n) and proportion (%). Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD. The test level was set on both sides, and α = 0.05 at p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data required to be classified were obtained from the corresponding authors of the study or were calculated through information processing. The unclassified group collected data that could not be grouped together.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search results and study characteristics

A total of 512 studies were identified through the initial search, whereas Endnote20 and manual screening eliminated repeat studies. A total of 245 studies were selected for screening after replication, of which articles were excluded during the title and abstract screening phase following inclusion and exclusion, leaving 98 articles eligible for full-text screening. From initiation to December 2021, 34 studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the final review (Supporting Information: S1). Detailed information for the 34 studies is shown in Table 1.

| Study | Time | Region | Cases, n | PGD, n | SGD, n | Gender, n | Age, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al.18 | 1998 | Central China | 101 | 96 | 1 | 70/31 | 1–14 |

| Zhang et al.19 | 2002 | North China | 110 | 86 | 0 | 64/46 | 10.2 ± 3.4 |

| Ye et al.20 | 2003 | South China | 244 | 178 | 63 | 166/78 | 8.3 ± 3.3 |

| Wang et al.21 | 2004 | East China | 218 | 135 | 57 | 120/98 | 8.6 |

| Dang et al.22 | 2007 | Central China | 1316 | 915 | 344 | 834/482 | 0–14 |

| Zhang et al.23 | 2008 | West China | 377 | 217 | 158 | 250/127 | 2.0–17.5 |

| Yang24 | 2009 | Central China | 246 | 104 | 136 | 153/93 | 12.4 |

| Liu and Wang25 | 2009 | West China | 216 | 172 | 42 | 122/94 | 9.8 ± 3.5 |

| Zheng et al.26 | 2011 | East China | 1419 | 907 | 329 | 850/569 | 8.1 ± 3.5 |

| Wu et al.27 | 2011 | Central China | 2887 | 2105 | 752 | 1662/1225 | 6.8 ± 4.2 |

| Feng et al.28 | 2012 | West China | 1000 | 742 | 246 | 524/476 | 9.2 ± 2.4 |

| Peng and Fu29 | 2013 | Central China | 896 | 635 | 261 | 591/305 | 2–17 |

| He et al.30 | 2013 | North China | 3090 | 2361 | 687 | 2078/1012 | 9.5 ± 4.1 |

| Pan et al.31 | 2013 | North China | 180 | 144 | 36 | 114/66 | 10.0 ± 1.8 |

| Xu et al.32 | 2013 | West China | 103 | 54 | 49 | 74/29 | 7.9 ± 3.2 |

| Li et al.33 | 2014 | East China | 977 | 755 | 183 | 546/431 | 7.5 |

| Yu34 | 2014 | West China | 116 | 103 | 11 | 64/52 | 1–17 |

| Wang35 | 2014 | North China | 187 | 150 | 37 | 112/75 | 9.3 ± 2.3 |

| Fu et al.36 | 2015 | East China | 353 | 206 | 135 | 216/137 | 0–17 |

| Rong et al.37 | 2015 | South China | 1313 | 921 | 312 | 824/489 | 9.3 ± 4.2 |

| Fang and Cui38 | 2015 | Central China | 313 | 254 | 41 | 200/113 | 7.5 ± 3.4 |

| Chen39 | 2015 | North China | 1708 | 1200 | 495 | 1049/659 | 11.7 ± 5.7 |

| Yao40 | 2016 | East China | 807 | 518 | 288 | 518/289 | 0–14 |

| Qiu41 | 2016 | South China | 211 | 211 | 0 | 132/79 | 7.8 ± 2.6 |

| Xiao42 | 2017 | South China | 196 | 120 | 74 | 123/73 | 10.8 ± 2.4 |

| Yang et al.43 | 2017 | East China | 156 | 138 | 18 | 77/79 | 7.9 ± 1.3 |

| Liu et al.44 | 2017 | East China | 753 | 428 | 306 | 442/311 | 8.7 ± 2.5 |

| Sun45 | 2018 | North China | 122 | 102 | 30 | 65/57 | 7.5 ± 1.3 |

| Wang et al.46 | 2018 | West China | 744 | 403 | 297 | 450/294 | 0–18 |

| Nie et al.47 | 2018 | All over China | 7962 | 5736 | 1885 | 5089/2873 | 13.5 ± 4.1 |

| Gao et al.48 | 2019 | East China | 9925 | 6564 | 2779 | 6371/3554 | 0–18 |

| Liu49 | 2019 | South China | 263 | 140 | 101 | 156/107 | 2.0–17.5 |

| Zhang et al.50 | 2019 | East China | 1136 | 846 | 253 | 685/451 | 8.1 ± 3.6 |

| Wang51 | 2020 | North China | 785 | 604 | 166 | 462/323 | 0–18 |

- Abbreviations: HGD, hereditary glomerular disease; PGD, primary glomerular disease; SGD, secondary glomerular disease.

3.2 Composition and characteristics of glomerular diseases in children

A total of 40,430 patients (aged < 18 years) were included in the study with a gender ratio of 1.66: 1. Glomerular diseases are mainly divided into three categories: primary glomerular disease (PGD), secondary glomerular disease (SGD), and hereditary glomerular disease (HGD) with gender ratios of 1.33: 1, 1.42: 1, and 1.28: 1, respectively.

A total of 28,280 (70%) patients were diagnosed with PGD by renal biopsy, while 10,547 (26.1%) patients were diagnosed with SGD, and 1146 (2.8%) patients were diagnosed with HGD. The most common diseases in PGD are minimal change disease (MCD), mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (MsPGN), IgA nephropathy (IgAN), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy (MN), endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis, (EnPGN), and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN). Additionally, the subgroup classification grades for SGD included Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis (HSPN), lupus nephritis (LN), hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis (HBV-GN), and ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). The classification of HGD mainly included thin basement membrane nephropathy (TBMN) and Al-port syndrome (Table 2).

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female), n | 25,253/15,177 |

| Primary glomerular disease | 16,130/12,150 |

| Secondary glomerular disease | 6184/4363 |

| Hereditary glomerular disease | 643/503 |

| Age, n (%) | |

| Infant (0 < age < 3) | 5234 (12.9) |

| Preschool (3 < age < 7) | 9661 (23.9) |

| Younger children (7 < age < 14) | 12,233 (30.3) |

| Adolescents (14 < age < 18) | 13,302 (32.9) |

| Group of periods, n (%) | |

| Period 1 (Before 2001) | 2473 (6.1) |

| Period 2 (Between 2001 and 2010) | 23,685 (58.6) |

| Period 3 (Between 2011 and 2021) | 14,272 (35.3) |

| Pathological subtypes, n (%) | |

| Primary glomerular disease | 28,280 |

| MCD | 8115 (28.7) |

| MsPGN | 7304 (25.8) |

| IgAN | 6250 (22.1) |

| FSGS | 2467 (8.7) |

| MN | 1600 (5.7) |

| EnPGN | 1196 (4.2) |

| MPGN | 848 (3.0) |

| Others | 735 (2.6) |

| Secondary glomerular disease | 10547 |

| HSPN | 6760 (64.1) |

| LN | 2524 (23.9) |

| HBV-GN | 804 (7.6) |

| AAV | 216 (2.1) |

| Other secondary lesions | 243 (2.3) |

| Hereditary glomerular disease | 1146 |

| TBMN | 712 (62.1) |

| AD | 409 (35.7) |

| Congenital urinary malformation | 25 (2.2) |

| Others | 457 |

- Abbreviations: AAV, ANCA-associated vasculitis; AD, Alport syndrome; EnPGN, endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HBV-GN, hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis; HSPN, Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; LN, lupus nephritis; MCD, minimal change disease; MN, membranous nephropathy; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; MsPGN, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis; TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy.

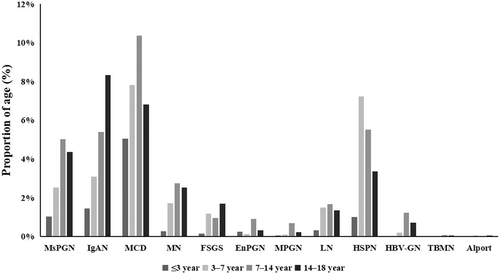

3.3 Composition of major glomerular diseases in four age groups

The four age groups were as follows: infant (12.9%), preschool (23.9%), younger children (30.9%), and adolescents (32.9%). Between age groups and disease subgroups, 22,397 patients were included in the analysis. Minimal change disease was the most common glomerular disease in infants (5%) and younger children (10.4%), while HSPN was the predominant diagnosis in preschools (7.2%), and IgAN was most common in adolescents (8.3%). The results are shown in Figure 1.

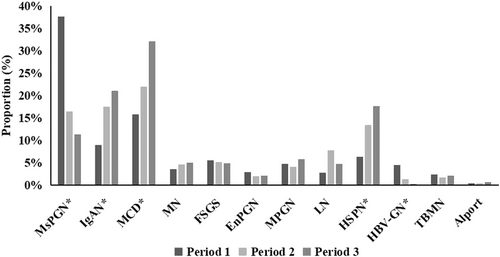

3.4 Composition of major glomerular diseases in three periods

According to the different study periods, it was divided into three periods: period 1 (6.1%), period 2 (58.6%), and period 3 (35.3%). Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (37.6%) was the most common childhood glomerular disease before 2001 (period 1), followed by MCD (15.7%), and IgAN (8.9%). Between 2001 and 2010 (period 2), the relative proportion of MCD (22%) surpassed that of IgAN (17.5%) as the predominant histological category of glomerular disease in children (Figure 2). The relative proportions of HSPN and LN increased significantly from 6.3% and 2.7%, respectively, in period 1 to 13.4% and 7.8%, respectively, in period 2.

The proportions of MsPGN and HBV-GN decreased significantly from 37.6% and 4.4% in period 1 to 11.3% and 0.3% in period 3, respectively. The proportions of MN, FSGS, EnPGN, MPGN, TBMN, and Alport were not significantly different between the groups in this study.

3.5 Composition of major glomerular diseases in four regions of China

The proportion of major glomerular diseases varied significantly in the different regions of China, as shown in Table 3. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (8.9%) and TBMN (1.7%) were most common in southern China, whereas MsPGN (24.1%) and MN (5.2%) were more common in northern China. Hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis (2.8%) was most common in Western China, while AD was more common in eastern China. No significant differences were observed in the relative proportions of other glomerular diseases.

| Regions | Cases, n (%) | Primary glomerular disease | Secondary glomerular disease | Hereditary glomerular disease | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCD | IgAN | MsPGN* | FSGS* | MN* | HSPN | LN* | HBV-GN* | TBMN* | AD* | ||

| North | 6182 (16.0) | 17 | 17.3 | 24.1 | 3 | 5.2 | 16.2 | 4.1 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| South | 13,948 (36.1) | 17.6 | 10.9 | 17 | 8.9 | 2.2 | 23.4 | 2 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1 |

| East | 15,744 (40.8) | 19.4 | 17.9 | 13.8 | 7 | 3.7 | 17.7 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| West | 2756 (7.1) | 24.1 | 10 | 20.8 | 4.3 | 2 | 22.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

- Note: *p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: AAV, ANCA-associated vasculitis; AD, Alport syndrome; EnPGN, endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HBV-GN, hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis; HSPN, Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; LN, lupus nephritis; MCD, minimal change disease; MN, membranous nephropathy; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; MsPGN, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis; TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy.

- a N = 38,630 pediatric cases performed a subgroup analysis of four regions.

4 DISCUSSION

This was a scoping review of biopsy-proven glomerular diseases in Chinese children. The importance of the present study lies in the extensive data provided on native renal biopsies in a large pediatric population over 30 years. We finally identified 34 retrospective studies in the present study, including 40,430 pediatric patients with definite renal diagnoses by renal biopsy. There were 28,280 (70%) patients who were diagnosed with primary glomerular disease (PGD), while 10,547 (26.1%) with SGD, and 1146 (2.8%) with HGD. Additionally, according to the subgroup analyses, we found significant differences among sex, age, study period, and regions. Our study provides detailed information on the pattern of pediatric glomerular diseases in China.

Birth and growth, as defined by the World Health Organization, are essential components of the social determinants of health.52 It has been reported that social, economic, and environmental conditions are associated with chronic diseases in children. Moreover, multiple adult studies have shown that problems caused by childhood environments persist during adulthood.53, 54 An equitably systematic review of adult dialysis reported that geographic remoteness and different residences were associated with a 54% increase in cardiovascular events and a 21% increase in mortality.55 Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the social needs of children. The cost of the children's healthcare system is relatively low. Compared to adults, higher healthcare spending in children is linked to better survival in renal replacement therapy.56, 57

There are differences in the spectrum of kidney diseases among different regions. Children in resource-poor and disease-aware settings are at a higher risk of kidney disease. Simple and convenient training of local medical staff in acute kidney injury care, such as peritoneal dialysis is required. Simultaneously, local government support is also needed to improve the awareness of clinicians, advocate for the significance of the biopsy-proven spectrum of kidney disease, and manage pediatric CKD to ameliorate the diagnosis and treatment of CKD in children around the world.58

Minimal change disease is the most common glomerular disease among Chinese children, followed by MsPGN, IgAN, and HSPN, consistent with previous research.47, 59 The proportion of MCD cases increased over time, which could be explained by the extensive use of electron microscopy for histopathology or by changing indications for renal biopsy.12 In our study, males had a higher proportion of pediatric glomerular disease than females, which is consistent with previous studies.5 This may be related to the higher number of boys in the population who appear to have an increased susceptibility to major glomerular diseases. Additionally, children >7 years old accounted for 63.2% of the total number of study patients in the study, which communicated and cooperated better with older children.

As shown in Table 4, the patterns of glomerular diseases in children vary by study and country. We present a summary of studies from seven different countries and regions, including one from, China. Minimal change disease is the most frequent glomerular disease diagnosis in children in some regions. The proportion of MCD in India and America accounts for more than 40% of PGD. In contrast, IgAN is reported to be the most common glomerular disease in Korea and Italy. In our study, IgAN was the third most common glomerular disease. In most of the published reports on biopsy-proven cases in China, HSPN is a secondary glomerular disease in children. However, studies from Hong Kong of China (67.3%), India (46.2%), and Arab countries (41.1%) indicated that LN is a common classification of SGD. The incidence of HGD, an important glomerular disease, has recently increased. However, the number of congenital and hereditary cases is lower than that of common glomerular diseases. Based on the rarity and diversity of HGD, we only collected AD and TBMN samples in the present study.

| Classification | China60 (2008) | America61 (2011) | Korea62 (2013) | India63 (2015) | Italy64 (2018) | Colombia65 (2018) | Arab66 (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, n | 161 | 129 | 1478 | 186 | 225 | 241 | 3083 |

| Primary glomerular disease, n (%) | 82 (51.0) | 86 (66.7) | 1128 (76.3) | 142 (76.3) | 138 (61.3) | 152 (63.1) | 2260 (73.3) |

| MCD | 28.0 | 40.7 | 11.5 | 46.5 | 28.3 | 30.9 | 29.3 |

| MsPGN | 15.9 | 19.8 | 31.8 | 1.4 | 10.1 | 8.6 | 14.8 |

| IgAN | 24.4 | 16.3 | 51.1 | 9.2 | 32.6 | 23.0 | 4.0 |

| FSGS | 14.6 | 14.0 | 1.5 | 24.6 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 22.3 |

| MN | 1.2 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 8.5 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 2.7 |

| MPGN | 2.4 | / | 2.2 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 1.3 | 6.9 |

| Secondary glomerular disease, n (%) | 55 (34) | 27 (21) | 71 (5) | 39 (21) | 32 (14.2) | 58 (24.1) | 708 (23) |

| HSPN | 23.6 | 12.4 | 42.3 | 17.9 | 43.8 | 22.4 | 1.7 |

| LN | 67.3 | 6.1 | 15.5 | 46.2 | 34.4 | 8.6 | 41.1 |

| HBV-GN | 1.8 | / | / | 30.8 | 21.9 | / | / |

| Heredity glomerular disease, n (%) | 24 (14.9) | 11 (8.5) | 207 (14) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (3.1) | 16 (6.6) | 98 (3.2) |

| AD | 20.8 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 20 | 42.9 | 18.8 | 38.8 |

| TBMN | 79.2 | / | 93.7 | 20 | 14.3 | 81.3 | / |

- Abbreviations: AAV, ANCA-associated vasculitis; AD, Alport syndrome; EnPGN, endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HBV-GN, hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis; HSPN, Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; LN, lupus nephritis; MCD, minimal change disease; MN, membranous nephropathy; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; MsPGN, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis; TBMN, thin basement membrane nephropathy.

From an evolving perspective, further exploration is required. The pattern of pediatric glomerulopathies in various studies might be due to differences in racial predisposition to different nephropathies, indications for renal biopsy, and patient referral. However, the effects of race, ethnicity, and geography were noted when comparing the distributions across regions. The importance of the environment and genetics in the incidence of glomerular diseases needs to be considered.63

We observed an increase in glomerular diseases in periods 2 (2001–2010) and 3 (2011–2021). Various reasons could explain the increase in pediatric renal biopsies over the past 20 years, such as improved renal biopsy safety and accessibility, the growing number of professionals and hospitals, the importance of renal histopathology, and more medical insurance coverage for children. The composition of glomerular disease changed significantly during the study period after controlling for the effects of possible confounders in the analysis. Additionally, the number of studies counted and research depth improved over the study period. However, compared to developed countries, pediatric patients in China have a higher risk of CKD. An increase in the number of pediatric patients with glomerular diseases results in an increase in renal endpoint events.

The limitations of this review were that it included studies on glomerular disease in children only and excluded those among young adults (aged 18–20 years) or without a biopsy-proven diagnosis. The correlation between pathological diagnosis and clinical features was not included in our review because of data acquisition. It is also an important assessment tool for children with glomerular disease. Thus, we refer readers to other reviews that address the spectrum of pediatric glomerular diseases from different perspectives.

The scoping review methodology enabled us to systematically summarize, synthesize, and analyze the composition and characteristics of pediatric patients in China. Moreover, the review allowed us to explore evidence regarding the evolving epidemiology of sex, age groups, different periods, and geographic location from initiation to December 2021. Additionally, the analysis of major pediatric glomerular diseases needs to be supplemented and refined in future studies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Wen Ge Li and Yue Yang did the study. Li Zhuo analyzed the data. Yetong Li and Yue Yang wrote the manuscript. Xiaorong Liu and Dan Wu were involved in the design, data management, and analysis of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funded by National key clinical specialty capacity building project No.2019-542. Pillar Program of National Science & Technology No.2015BAI12B06.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Professor Wenge Li is a member of Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine editorial board and is not involved in the peer review process of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.