Development of Surgical Site Infection One Year After Thyroplasty With Arytenoid Adduction

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Delayed complications of arytenoid adduction and medialization laryngoplasty are rarely reported in the literature. Clinicians should be aware that performing an AA alongside an ML may seed oral cavity bacteria into the paralaryngeal space. This may result in delayed infection—especially in immunocompromised patients—necessitating implant removal and antibiotics.

1 Introduction

Unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP) is characterized by incomplete glottic closure and decreased vocal fold tension, leading to symptoms such as dysphonia, dyspnea, dysphagia, and increased risk of aspiration that can severely impact quality of life [1]. Medialization laryngoplasty (ML), also known as type 1 thyroplasty, and arytenoid adduction (AA) are types of laryngeal framework surgery (LFS) performed to improve phonation and swallowing in UVFP. In a survey of otolaryngologist-performed LFS, Young et al. found that ML procedures had a total complication rate of 15.4%, with implant revision or extrusion, suboptimal voice outcome, and airway compromise requiring intervention being the most common complications [2].

ML involves placing an implant into a rectangular window incised in the thyroid cartilage lateral to the true vocal fold, which manually medializes the true vocal fold [1]. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, otherwise known as Gore-Tex, implants are commonly used for ML due to their ease of use, biocompatibility, and low complication rates of about 2% [3]. AA is often performed independently or alongside ML to treat UVFP. The technique involves suturing the muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage to the anterior wall of the thyroid cartilage, mimicking the action of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle [1].

We present a case of a ML and AA with a Gore-Tex implant complicated by infection 1 year after placement. To our knowledge, only one other case of delayed infection of a laryngeal implant procedure has been reported [4].

2 Case History

This study was determined to be IRB exempt, as it was a case report. A 64-year-old male with a history of Human Immunodeficiency Virus controlled with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) presented to our institution for idiopathic right vocal fold paralysis. After he successfully underwent a ML with a Gore-Tex implant and AA, his postoperative course was initially unremarkable, with satisfactory voice improvement. Pre- and postoperative Voice Handicap Index (VHI-10), Cough Severity Index (CSI), Dyspnea Index (DI), Singing Voice Handicap Index (SVHI-10), and Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) are summarized in Table 1.

| Preoperative | Postoperative | |

|---|---|---|

| VHI-10 | 32 | 14 |

| CSI | 0 | 0 |

| DI | 0 | 0 |

| SVHI-10 | 0 | 0 |

| EAT-10 | 0 | 10 |

- Abbreviations: CSI, Cough Severity Index; DI, Dyspnea Index; EAT-10, Eating Assessment Tool; SVHI-10, Singing Voice Handicap Index; VHI-10, Voice Handicap Index.

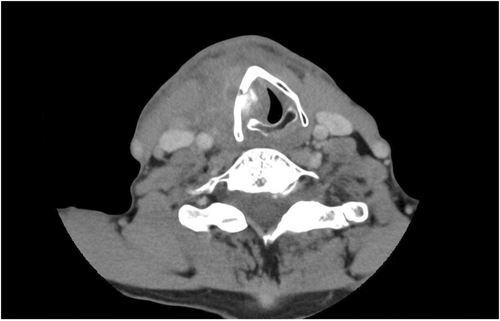

However, around 9 months postoperatively, the patient developed odynophagia with worsening vocal quality and was diagnosed with laryngeal candidiasis due to white, plaque-like deposits over the right pyriform sinus and arytenoid. His VHI-10 at the time was 33. A prolonged course of antifungal medication was ultimately unsuccessful, suggesting the involvement of bacterial infection, and the patient presented to our university emergency department 1 year postoperatively with symptoms of stridor, fever, right-sided neck swelling, and odynophagia. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated an abscess over the right thyroid lamina (Figure 1). Subsequent laryngoscopic examination demonstrated arytenoid edema and significant erythema of the right vocal fold (Figure 2).

3 Diagnosis/Treatment

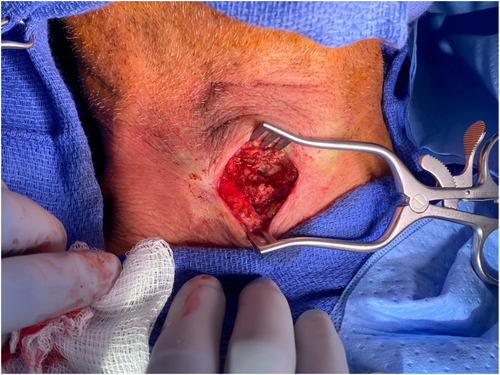

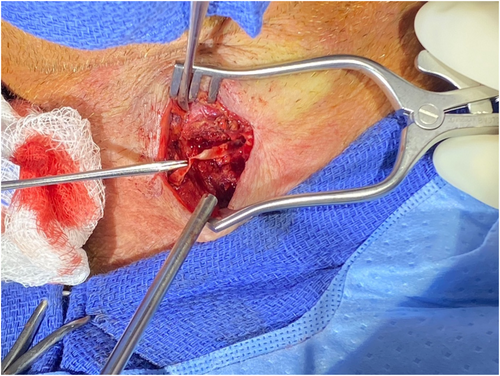

Surgical exploration revealed an abscess pocket directly overlying the site of the previously created laryngoplasty window in the right paralaryngeal space (Figure 3). Following drainage of the purulent exudate, the previously placed Gore-Tex implant was found intact without evidence of extrusion (Figure 4). The surgeon elected to remove the laryngeal implant due to its proximity to the abscess pocket and uncertainty about the source of infection. Further examination into the paraglottic space revealed unexpected minimal purulence, suggesting that the infection originated outside the paraglottic space. The AA suture was left undisturbed to await inspection after antibiotic treatment.

4 Conclusion and Results

Cultures of abscess aspirate grew common oral cavity flora, such as Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Following implant removal, the patient was placed on a two-week course of intravenous Augmentin. Right-sided laryngeal edema, odynophagia, and overall vocal quality improved, with a VHI-10 of 33 preoperatively and 21 postoperatively. Due to satisfactory improvement, the AA suture was electively left in. Of note, T-cell subset testing, in the form of CD4:CD8 ratio, was found to be normal at several measurements taken before surgery, postoperatively, and after implant removal and symptom resolution.

5 Discussion

LFS complications using Gore-Tex implants are uncommon, with delayed infectious complications even rarer as evidenced by the lack of reported cases in the literature [2]. This case report illustrates a previously successful ML and AA that was complicated by the development of a surgical site infection nearly a year after the initial procedure, ultimately necessitating removal of the implant. To our knowledge, only one previous example of delayed infection after ML, reported by Meleca et al., exists in the literature. In contrast to our case, the authors described the delayed infection of a silastic laryngeal implant by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a patient with a history of Clostridium difficile infection. The authors also note that the infection was localized to a laryngocutaneous fistula communicating with the anterior paraglottic space [4].

To our knowledge, our patient did not have any evidence of a gross laryngocutaneous fistula. Instead, the abscess pocket was confined to the external surface of the thyroid cartilage around the surgically created laryngoplasty window with no signs of infection in the paraglottic space. Coupled with the presence of anaerobic oral cavity bacteria, which are associated with polymicrobial infections in immunocompromised hosts, it is possible that bacteria were seeded into the paralaryngeal space from a fistula formed due to mucosal microperforation from the AA suture [5]. However, no actual fistula was visualized. Conversely, due to the degree of inflammation in the vocal fold, it is possible that the paraglottic space may have been infected, as the AA suture travels through the paraglottic space where it is then delivered inferiorly and through the thyroid cartilage. In our case, the Gore-Tex implant was unlikely the nidus for infection due to the lack of purulence found in the paraglottic space. We do take into account that foreign bodies, including laryngeal implants, are ideal sites for biofilm formation, and preemptive removal is recommended in cases of nearby infection, as was done in our case [6]. Despite the removal of the implant, the patient's symptoms of odynophagia and dysphonia improved, indicated by his preoperative and postoperative VHI-10 of 33 and 21, respectively. This was likely because the AA suture was left intact, providing vocal fold tension. The increase in the EAT-10 from 0 preoperatively to 10 postoperatively is expected, as odynophagia is a common acute postoperative complication due to the surgical manipulation of the airway and the piriform sinuses posteriorly. Subsequent postoperative visits indicated that the patient's odynophagia improved.

A list of abbreviations can be found in Table 2.

| Term | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Unilateral vocal fold paralysis | UVFP |

| Medialization laryngoplasty | ML |

| Arytenoid adduction | AA |

| Laryngeal framework surgery | LFS |

| Highly active antiretroviral therapy | HAART |

| Voice Handicap Index | VHI-10 |

| Cough Severity Index | CSI |

| Dyspnea Index | DI |

| Singing Voice Handicap Index | SVHI-10 |

| Eating assessment tool | EAT-10 |

| Computed tomography | CT |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | MRSA |

Author Contributions

Ethan Simmons: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Wilson P. Lao: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing. Nihal Punjabi: formal analysis, project administration, validation, writing – review and editing. Priya Krishna: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

This case report was exempt from IRB approval.

Consent

Written patient consent was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.