HUSM endocarditis team's approach to acute ruptured chordae tendineae in chronic rheumatic heart disease

Key Clinical Message

Neglected rheumatic heart disease (RHD) can lead to severe complications and change patients' quality of life, particularly that of young patients. This report highlights the importance of public health education for patients and families in preventing RHD complications. In RHD management, prevention is better than cure.

1 INTRODUCTION

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a neglected chronic disease in many regions of the world, particularly in low-resource settings. This condition is usually associated with overcrowded populations, poor housing conditions, and a lack of health education. According to the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study, the prevalence of RHD increased by 70.49% from 1990 to 2019, and individuals aged 25–29 years were the most affected age group.1 Based on geographic area, the prevalence of RHD is the lowest in Eastern Europe, followed by high-income Asia–Pacific countries and Central Europe.2 A recent prevalence study of RHD in Malaysia showed that 14 in 1000 school-going-age children are affected by this disease.3 In Malaysia, RHD remains endemic and is neglected because of a lack of awareness and healthcare resources for its early prevention. Herein, we report a case of a young patient with neglected RHD complicated by acute ruptured chordae tendineae who underwent prompt surgical intervention in a teaching hospital.

2 CASE HISTORY

A 29-year-old man, active in sports, presented to our center with intermittent fever for 2 months. The fever was described as intermittent high-grade fever with chills and rigor associated with weight loss and loss of appetite. These symptoms persisted despite several antibiotics given by a private practitioner. He had a history of RHD that was diagnosed in childhood. However, he defaulted on all follow-ups, including antibiotic prophylaxis and echocardiography, because he believed that he was well. Additionally, he had undergone endodontic treatment for the past 2 years without any antibiotic prophylaxis. On examination, his BP was 100/60 mmHg, PR was 112 beats per minute, and temperature was 38.6°C. Finger clubbing and Roth spots over the right eye were present, suggesting subacute infective endocarditis. Examination of the precordium revealed a displaced apex beat and a soft first heart sound with a grade 3 pansystolic murmur over the mitral, radiating to the axilla. A complete blood count showed hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dL, total white cells of 16.2 × 109/L, and platelet count of 273 × 109/L, with normal renal and liver function.

3 METHODS: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, INVESTIGATIONS, AND TREATMENT

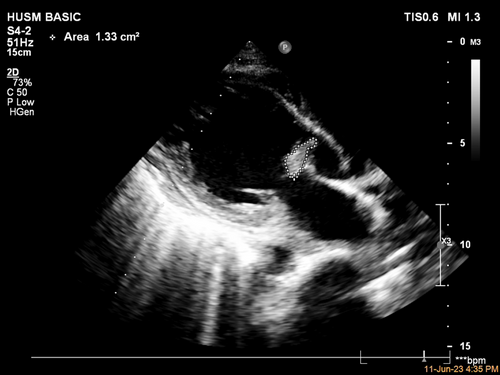

Sputum cultures showed Streptococcus viridans, but blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed severe mitral regurgitation with anterior mitral valve vegetation of 1.4–2.1 cm2 in size (Figure 1, Videos 1 and 2); thus, mitral valve infective endocarditis was diagnosed. Treatment included 3 million units of benzylpenicillin every 4 h, 2 g of cloxacillin every 4 h, and 120 mg of gentamicin once daily. Benzylpenicillin was initially used according to the Malaysian national guidelines for managing infective endocarditis. Meanwhile, cloxacillin and gentamicin were selected to empirically treat Staphylococcus aureus infection.

However, on the third day of antibiotics, he experienced sudden onset shortness of breath and diaphoresis, with blood pressure dropping to 84/60 mmHg, pulse rate rising to 130–140 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation dropping to 70% under room air. Clinical reassessment revealed severe acute heart failure and a loud pansystolic murmur. Intravenous adrenaline, intravenous furosemide, and mechanical ventilation were administered for resuscitation. Urgent transthoracic echocardiography showed evidence of a ruptured anterior mitral valve chordae tendineae with severe mitral regurgitation (Videos 3 and 4), indicating critical deterioration.

Given his sudden deterioration, he underwent emergency surgery for acute severe congestive heart failure secondary to ruptured chordae. This decision was made by consensus among the endocarditis team, consisting of a cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, cardiac anesthesiologist, and infectious disease physician, who decided to perform an emergency procedure to save the patient's life despite the limited resources at our center.

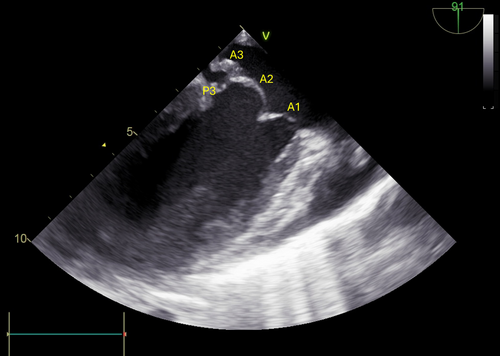

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography revealed ruptured anterior mitral chordae involving A2 and A3 scallops (Video 5). A conventional primary median sternotomy was performed, revealing serous pericardial effusion upon entering the pericardium, with dilated left atrium and ventricle displaying good contractility. Cardiopulmonary bypass with bicaval venous cannulation was established, lowering the patient's temperature to 32°C and using cold blood micro-cardioplegia solution with a total cross-clamped time of 60 min.

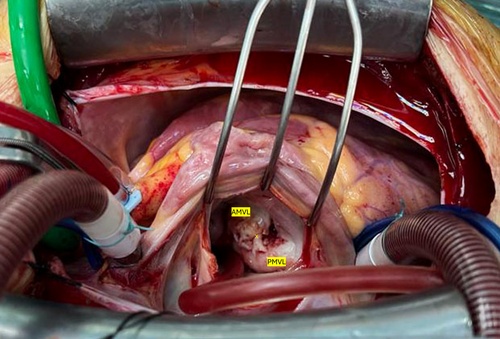

A standard left atriotomy was used to access the mitral valve, revealing vegetation at the anterior mitral valve leaflet at the A2 and A3 areas, involving ruptured chordae (Figures 2 and 3). Additionally, there was vegetation over the posterior mitral valve leaflet at the P2 and P3 areas, involving the mitral annulus. The subvalvular apparatus appeared thickened, with a jet lesion detected together with vegetation on the left atrial wall near the P3 area, extending down to the opening of the left inferior pulmonary vein. Opting for a mechanical valve replacement strategy due to irreparable damage, the anterior and most of the posterior mitral valve leaflets and infected tissue were excised. A neochordae between the posteromedial papillary muscle and annulus at the P2 area was created using a 3/0 Gore-Tex suture for valve stability. A size 33 CE Medtronic mechanical valve was implanted with 14 valve sutures along the annulus. Cardiopulmonary bypass time was 100 min, terminated after rewarming.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND RESULTS: OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

He was extubated on postoperative day 2, and he experienced cardiac tamponade after removal of cardiac pacing, which was successfully managed. After completing a 6-week course of intravenous cloxacillin and benzylpenicillin after endocarditis surgery, he was discharged on oral warfarin. The patient was under regular follow-up at the outpatient clinic. Serial echocardiography showed adequate mechanical mitral valve function with good time in the therapeutic range of warfarin. After the occurrence of this acute event, the patient became aware of the disease. He recovered well with satisfactory compliance with the warfarin clinic follow-up.

5 DISCUSSION

Acute chordae tendineae rupture leads to acute severe mitral regurgitation, a recognized complication of infective endocarditis. Antibiotic use has become common, and chronic RHD leading to infective endocarditis is rare. RHD is uncommon globally, with a decreasing trend in mortality.1 However, RHD is an endemic disease in Malaysia, and it remains a neglected disease among patients and healthcare professionals because most patients are asymptomatic.2 A recent review showed that the burden of RHD in the adult population was 77.1%, and the number of patients requiring mitral valve intervention increased from 55.8 patients per year in 1997 to 184 patients per year in 2012.2, 3 Because patients are asymptomatic, they have a higher predisposition to defaulted follow-up and treatment.

Based on the 2020 Australian guidelines for preventing, diagnosing, and managing RHD, secondary prophylaxis is an important strategy to reduce the risk of complications.4 Multidisciplinary patient-centered care comprises patient education, family support, and, moreover, regular administration of long-acting benzathine benzylpenicillin G to prevent future infection.4 In Malaysia, only 44.7% of patients with RHD on follow-up were administered with intramuscular antibiotic prophylaxis.3 We presented a case of chronic RHD complicated by infective endocarditis and ruptured chordae tendineae, which were the consequences of an inadequate RHD secondary prophylaxis plan previously given to this patient. Male sex, age >50 years, posterior mitral valve thickening, and chordal elongation with floppy mitral valve are risk factors associated with chordal rupture in rheumatic mitral valve disease.4 In our case, a floppy anterior mitral valve with the presence of infective endocarditis placed the patient at a higher risk of developing acute ruptured chordae. Infective endocarditis makes the valve tissue friable and easily ruptured. Hence, a detailed assessment of valves on transthoracic echocardiography is vital for predicting outcomes of infective endocarditis. Poor dental hygiene, including dental caries and periodontal disease, is a common cause of infective endocarditis among patients with RHD.5, 6 Our patient had undergone endodontic treatment for dental caries for 2 years, potentially increasing the risk of bacteremia and infective endocarditis. These findings indicate that a lack of information and understanding of the disease and simple prevention strategies can lead to catastrophic complications.

Acute ruptured chordae is a mechanical complication requiring emergency surgery in infective endocarditis cases. Surgery for infectious endocarditis is technically challenging and associated with high-risk complications, with the aim of controlling infection and reconstructing cardiac morphology.7, 8 Infective endocarditis is a pathological process in which microorganisms adhere to damaged valves and lead to vegetation. These microorganisms produce and release enzymes that disintegrate tissue and cause valve destruction.9, 10 Despite receiving multiple antibiotic courses before hospital presentation, our patient's infection was not fully recognized or controlled, leading to mechanical complications. According to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, we initiated benzylpenicillin and gentamicin and empirically treated the patient with cloxacillin for Staphylococcus aureus.11 Gentamicin has been reported to improve the antibiotic penetration effect in biofilm-associated infection.10 Biofilm-associated infections make the treatment of infective endocarditis challenging, and some patients require surgery.

The mechanical complication likely resulted from fibrotic chordae and significant elongation due to existing RHD. According to the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the endocarditis team approach is mandatory for successful surgical outcomes.7 In our center, the resources to manage patients requiring infective endocarditis surgery are limited (one cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, cardiac anesthesiologist, and infectious disease expert). Despite this limitation, we decided to perform emergency surgery for infective endocarditis in this young patient. An indication for urgent or emergency surgery for left-sided infective endocarditis is the presence of valve dysfunction caused by S. aureus despite the ongoing therapeutic course of antibiotics.7 However, infective endocarditis surgery is challenging, as it requires a thorough presurgical workup, including neurological assessment and explanation of surgical risks. Furthermore, performing transesophageal echocardiography before, during, and after surgery is necessary to improve surgical outcomes.7

It is important to remove all infected material, foreign bodies, and necrotic tissue during surgery to minimize the residual infection burden and to provide optimal access to antibiotic therapy.7, 8 Surgery proceeded uneventfully with mechanical valve replacement and neochordae construction. In this patient, the initial surgical plan was to perform mitral valve repair because the patient was young and was expected to have issues with anticoagulation treatment compliance. However, intraoperatively, the patient required mechanical valve replacement and neochordae construction because the infection severely damaged the valve. Postoperatively, we decided to continue antibiotics for another 6 weeks because of the endemic and indolent RHD, which could cause relapse. Given the high risk for additional valvular disease, his aortic valve was not replaced. This case highlights a known complication of a neglected disease, effectively managed by the endocarditis team despite the limited resources.

Although this case demonstrated successful infective endocarditis surgery, RHD management required long-term management and follow-up. In our patient with RHD who underwent surgical valve replacement, long-term management was vital, especially anticoagulation therapy. Given that the patient had a history of neglected RHD, comprehensive counseling and follow-up were planned, including dietary modification and annual transthoracic echocardiography surveillance.12 These measures are important to reduce the risk of valve thrombosis. Although the valve was replaced, lifelong secondary antibiotic prophylaxis will continue because RHD is endemic and the patient's aortic valve was not replaced, which leads to a residual risk of infective endocarditis. Furthermore, aggressive public health interventions should be one of the strategies to eliminate RHD in Malaysia.

Acute ruptured chordae secondary to infective endocarditis in RHD is a well-known complication. However, no case has been reported in the last decade. This may be because the incidence of RHD is decreasing in most countries, and most patients with RHD are well under follow-up.1 Hence, given that our world is easily connected, a high index of suspicion for RHD and its complications should be part of clinical judgment when treating patients from an endemic country for RHD.

6 CONCLUSION

RHD is still an endemic and neglected disease in this part of the world. Poor knowledge and awareness of this disease potentially lead to increased morbidity and mortality among young people. An endocarditis team consisting of a cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, infectious disease specialist, and cardiac anesthesiologist with supporting paramedics is important in managing a complicated case of infective endocarditis due to existing undiagnosed RHD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mohd Khairi Othman: Conceptualization; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Anis Alyani Abdullahilhai: Writing – original draft. Zurkurnai Yusof: Project administration; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. W. Yus Haniff W. Isa: Conceptualization; project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Alwi Muhd Besari: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Ariffin Marzuki Mokhtar: Writing – review and editing. Aimatnuddin Husairi Hussain: Writing – original draft. Mohamad Hasyizan Hassan: Writing – review and editing. Ahmad Zuhdi Mamat: Writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the important contribution of the healthcare personnel involved in the treatment of the patient, the Cardiology Unit, Cardiothoracic Unit, Cardiac Anesthesiology Unit, and Pathology Department, Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The local ethical committee approval does not apply in this case.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this manuscripts are available from the corresponding author upon request.