Whitaker syndrome: A case report of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 with dilated cardiomyopathy

Abstract

Key Clinical Message

This case report highlights dilated cardiomyopathy as a cardiovascular complication in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1), emphasizing the need for early recognition and a multidisciplinary approach. Comprehensive care and regular follow-up are crucial in managing these atypical presentations to optimize patient outcomes.

APS-1, also known as Whitaker syndrome, is characterized by a triad of mucocutaneous candidiasis, adrenal insufficiency, and hypoparathyroidism. This rare autosomal recessive disorder results from mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene. Cardiovascular and pulmonary manifestations in APS-1 are infrequently reported in the literature. We present a case of a 28-year-old male who presented with shortness of breath and pedal edema. Physical examination revealed alopecia, absence of eyebrows, hyperpigmentation on joints, oral candidiasis, and nail dystrophy. Echocardiography demonstrated dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and pericardial effusion. Chest x-ray showed left-sided pleural effusion. Laboratory investigations revealed hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, low parathyroid hormone (PTH), low cortisol, and high adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels. The combination of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), hypoparathyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency confirmed the diagnosis of APS-1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Pakistani and second worldwide reported case of APS-1 presenting with such a combination of manifestations. Early recognition and multidisciplinary management are crucial for improving outcomes in these patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

APS-1 is a rare autosomal recessive disorder affecting approximately 10 per million individuals.1 The presence of one out of the triad of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), chronic hypoparathyroidism (CH), and Addison's disease defines a probable case of APS-1, while a definitive case requires at least two of these manifestations.1 Mutations in the AIRE gene on chromosome 21 (21q22.3) underlie this condition.1, 2 The pathogenesis involves the development of T cells with a high affinity to auto antigens; a defect in the immune system prevents the elimination of these T cells, which then attack the host's cells. This classic triad was recognized in 1946, although the association between parathyroid deficiency and mucocutaneous candidiasis was first described by Thorpe and Handley in 1929.3 In addition to the endocrine organs (parathyroid, adrenals, thyroid, gonads, and pituitary), APS-1 can affect non-endocrine organs such as the skin, liver, kidneys, lungs, eyes, and intestines.9 Cardiovascular manifestations due to adrenal crises are reported in the literature but are rare. A case of left ventricular systolic dysfunction related to adrenal insufficiency due to APS-1 was previously reported by Yavuz Özer et al.4 We present a case of an southeast Asian patient diagnosed with APS-1 at an early age who developed cardiovascular manifestations in his twenties.

2 CASE HISTORY

A 28-year-old male patient presented to the outpatient department with complaints of shortness of breath and bilateral foot swelling for 3 months. At the age of seven, he developed alopecia and loss of eyebrows, along with peripheral tingling and numbness. He experienced an episode of generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTC) and was hospitalized for 30 days in an altered sensorium. He also reported recurrent oral white patches (Figure 1). On examination, he had a bald appearance without eyebrows, a thin and pale body with dark knuckles (Figure 2), nail dystrophy (Figure 3), and pedal edema.

3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, INVESTIGATIONS, AND TREATMENT

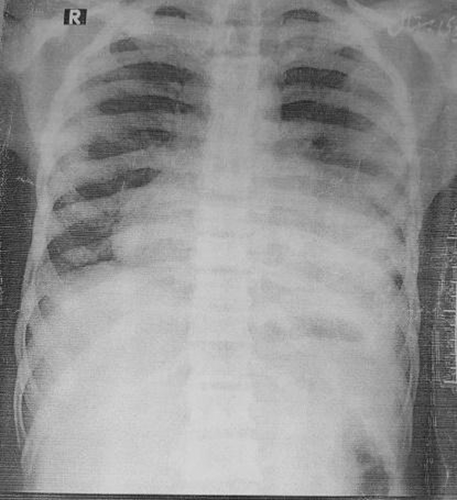

Differential diagnoses included mucocutaneous candidiasis, alopecia, and anemia. Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed epileptiform activity, and MRI of the brain revealed bilateral basal ganglia calcification (Figure 4). Laboratory investigations showed low hemoglobin (4 g/dL), hypocalcemia (6.1 mg/dL), low parathyroid hormone (PTH; 1.90 pg./mL), low morning cortisol (13.2 μg/dL), and hyperphosphatemia (6.8 mg/dL). Serum sodium, potassium, magnesium, IgE, and TSH levels were normal, and antinuclear antibody (ANA) and extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) profiles were negative. Anti-acetylcholine receptor and anti-transglutaminase antibodies were also negative. Oral and skin scrapings tested positive for Candida. Based on clinical and laboratory findings, he was diagnosed with APS-1. Echocardiography (Table 1) revealed dilated left ventricle (LV) with global hypokinesia, severe systolic dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy, and pericardial effusion with an ejection fraction (EF) of 35%. Chest x-ray showed left-sided, mild pleural effusion (Figure 5). In emergency, diuretics were given, and urine output was monitored, thus improving his shortness of breath. After admission to the ward, carbamazepine was continued for epilepsy, and nystatin drops were prescribed for oral candidiasis. Combination of spironolactone and furosemide, losartan, iron, calcium, and vitamin D supplements were administered along with blood transfusion.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Aortic root | 26 mm |

| LVEDD (LV end-diastolic diameter) | 56 mm |

| LVESD (LV end-systolic diameter) | 40 mm |

| IVS (interventricular septum) | 9 mm |

| PW (posterior wall) | 9 mm |

| EF (ejection fraction) | 35% |

| RV (right ventricle) | Normal |

| RA (right atrium) | Normal |

| LA (left atrium) | Dilated(52 mm) |

| LV (left ventricle) | Dilated with global hypokinesia with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure | 35 mmHg |

| Mitral valve | Annular dilatation of mitral valve with moderate MR |

| Aortic valve | Normal |

| Tricuspid valve | Structurally normal |

| Pulmonary valve | Structurally normal |

| Color flow mapping | Mild MR, TR |

| Doppler | Normal |

| Pericardium | Normal (14 mm), pericardial effusion posteriorly, around RA (22 mm), and anteriorly (12 mm) |

4 OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Upon discharge, his calcium level was 8.5 mg/dL, and hemoglobin was 8.0 g/dL. Post-discharge, he was prescribed antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine), vitamin D, and calcium supplements. He was advised to follow-up regularly and consult a cardiologist.

The patient's symptoms were improved during hospital stay and he was asked to follow-up in the outpatient clinic with a fresh echocardiogram, chest x-ray, and necessary laboratory investigations. On follow-up after 3 months, his symptoms were settled, and calcium and hemoglobin profiles were improved.

5 DISCUSSION

The clinical presentation of APS-1 often begins in early childhood, with complete manifestation of the classic triad typically occurring within the first two decades of life. The syndrome is caused by mutations in the AIRE gene that leads to a failure in eliminating self-reactive T cells, resulting in autoimmunity against various endocrine and non-endocrine organs.5 Our patient's clinical presentation likely stems from the underlying pathophysiology of APS-1. The hypocalcemia and seizures are due to autoimmune hypoparathyroidism, while the generalized alopecia, nail dystrophy, and mucocutaneous candidiasis result from immune-mediated destruction of hair follicles and chronic fungal infections. The presence of low cortisol and systemic features like cardiomyopathy suggest adrenal insufficiency, contributing to fluid retention and pedal edema. The constellation of these findings aligns with the multi-system autoimmune nature of APS-1.

Cardiovascular complications in APS-1 are uncommon but have been reported in association with adrenal insufficiency. For instance, Yavuz Özer et al. documented a case of left ventricular systolic dysfunction linked to adrenal insufficiency in a patient with APS-1.4 The pathophysiology behind these cardiac manifestations may involve chronic hypocalcemia, which can adversely affect myocardial function.7 Additionally, autoimmune myocarditis could contribute to the development of DCM and pericardial effusion.4

Pulmonary manifestations in APS-1 are equally rare. In our case, the patient exhibited pleural effusion. This association raises important considerations about the susceptibility of APS-1 patients to opportunistic infections, likely due to their compromised immune status. Previous literature has reported respiratory complications in APS-1, such as a case involving a 16-year-old female with pulmonary manifestations.6 However, the interplay between APS-1-induced immunodeficiency and susceptibility to infections needs further exploration.

Management of APS-1, particularly with complex presentations involving multiple organ systems, necessitates a multidisciplinary approach.8 Given the chronic nature of APS-1 and its propensity to affect multiple organ systems, regular follow-up and comprehensive management plans are critical. Endocrinologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists, and infectious disease specialists must collaborate to optimize patient outcomes. Hormone replacement therapy, vigilant monitoring for infections and supportive cardiac care are essential components of the treatment strategy.2, 3

6 CONCLUSION

The unique clusters of clinical manifestations, especially the cardiac manifestations of Whittaker syndrome are the hallmarks of this case report. The significant cardiac compromise could be attributed to the autoimmune pathophysiological mechanisms. Routine cardiac evaluation is warranted in patients with APS-1 syndrome. Multidisciplinary consultation with active management ensures satisfactory prognosis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ali Gohar: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Bilal Ahmed: Project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Shahroz Azhar: Data curation; formal analysis; project administration; resources; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Aqsa Iqbal: Validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Ali Usman: Validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Muhammad Husnain Ahmad: Validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Masab Ali: Supervision, formal analysis; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Muhammad Daim Jawaid: validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the team of clinicians who helped manage this case. We would like to thank the patient and his family members for their cooperation in bringing this case for the betterment of the scientific community.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors did not receive any funding for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was not required for this case report.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data and materials available upon request from corresponding author.