Aberrant origin of the left coronary artery from the right coronary sinus with a common orifice with the right coronary artery

Key Clinical Message

In patients with anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery, accurate classification is essential for effective management. Despite surgical refusal, successful stenting and medication can lead to favorable outcomes. Regular monitoring ensures ongoing cardiac health.

Coronary artery anomalies, including anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva, are rare occurrences with varying clinical significance. Accurate classification of these anomalies is crucial for determining their implications and guiding management. A 50-year-old man presented with chest pain and was diagnosed with an anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery. Despite refusing surgery, successful stenting and medication led to a favorable outcome. Regular monitoring is scheduled. Accurate classification of coronary anomalies, such as the left main coronary artery anomaly described, is vital for effective management. Even when surgical intervention is declined, alternative treatments, such as stenting, can be successful. Regular monitoring ensures ongoing cardiac health.

1 INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery anomalies are rare, occurring in approximately 0.8%–1.3% of patients.1 While most anomalies are asymptomatic and diagnosed postmortem, some can lead to ischemic symptoms and sudden death. Anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva is a particularly rare occurrence with implications for early cardiac mortality.2 High-risk ischemia-producing anomalies include anomalous origin of coronary arteries from the pulmonary trunk or opposite aortic sinus, single coronary artery, and hypoplastic coronary arteries.3 There are three anatomical types of these anomalies, with Type 2 being the most serious and associated with a significant risk of sudden cardiac death. Proper classification of coronary anomalies is crucial for determining their clinical significance and management strategies.4 We present a case study of a coronary anomaly with the left main ostium originating from the right coronary cusp. It is important to note that nonischemic anomalies without clinical risk include a single coronary anomaly, RCx arising from the right coronary sinus, and separate ostia of all three arteries. The clinical significance of these anomalies depends on their type.

2 CASE HISTORY/EXAMINATION

A 51-year-old man with a smoking history of 30 pack-years and no history of alcohol consumption presented with substernal chest pain for 2 days, accompanied by nausea, which was unresponsive to nitroglycerin. The patient had chronic constipation but no complaints related to the urinary, genital, or endocrine systems.

3 METHODS

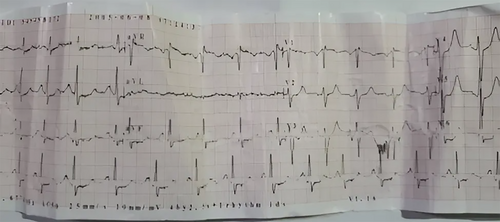

Clinical examination revealed a blood pressure of 150/95 mmHg, a pulse rate of 80 beats per minute, a temperature of 36.9°C, and a respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute. The head and neck examination showed bilateral conjunctival hyperemia and geographic tongue but no jugular distention. The chest is clear without crackles, and examination of the heart revealed a point of maximal impulse (PMI) on the fifth intercostal space left to the sternum extending over the first intercostal with regular S1, S2, and S4. The ECG shows sinus tachycardia of 135 bpm, ST segment depression in leads V2–V6, II, III, and aVF, and ST segment elevation in lead V1 and aVR (Figure 1).

The patient underwent an echocardiogram, which revealed an aortic root measuring 3.8 cm, a left atrium measuring 3.2 cm, a left ventricle with an ejection fraction (EF) of 60%, and physiological tricuspid insufficiency with a gradient of 10 mm Hg and a systolic pulmonary tension (SPAP) of 15 mm Hg. Laboratory test results showed WBC 9.2 × 10^3/μL, RBC 5.3 × 10^6/μL, HB 15 g/dL, MCV 83 fL, PLT 190 × 10^3/μL, RDW 12%, Cr 0.6 mg/dL, Ur 23 mg/dL, fasting glucose 88 mg/dL, Na 140 mmol/L, K 4 mmol/L, CKMB 6 ng/mL, and Troponin 0.1 ng/mL. All laboratory tests are within the normal range, except for high blood pressure.

The patient underwent coronary angiography with right radial access, which showed an anomalous origin of the left main from the right coronary sinus, 85% stenosis of the middle anterior descending artery (LAD), and 95% stenosis at segment 3 of the right coronary artery (Figure 2). The patient refused surgery and instead underwent right and descending anterior stenting in one session with two DES implants, resulting in an excellent final outcome (Figure 3).

4 CONCLUSION AND RESULTS

The patient was prescribed medication, including 162 mg of aspirin, 75 mg of clopidogrel, 40 mg of pantoprazole, 2.5 mg of bisoprolol after lunch, and 40 mg of rosuvastatin in the evening. The patient was scheduled for periodic monitoring every 6 months.

5 DISCUSSION

Coronary anomalies are rare but potentially serious and have been studied extensively using anatomically-based classification systems. The most prevalent anomaly is the circumflex coronary artery arising from the right sinus or the RCA.5 The next most common and clinically significant anomalies are the right coronary artery originating from the left sinus of Valsalva and the left main coronary artery arising abnormally from the right sinus of Valsalva. A study using coronary angiography showed an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery forming a common ostium with the right coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva.5

An anatomically-based classification system for coronary anomalies proposed by Shirani and Roberts encompasses all possible anatomical variations, regardless of whether or not they have been previously reported.6 In numerous instances of the anomaly where the left main artery courses between the aorta and pulmonary artery, it has been postulated that the heightened cardiac mortality is due to compression of the left main artery between the great vessels.2 However, other studies have reported cases of myocardial infarctions in which the left main artery originated from the right sinus of Valsalva but did not course between the great vessels. Numerous autopsy studies have revealed a high incidence of sudden death in young, athletic males with this anomaly. Sudden death occurred in 57% of these patients, with a higher frequency (64% of cases) during or shortly after exercise. Younger patients (under 30 years old) were significantly more likely to experience sudden death or death during exercise than older patients (over 30 years old).4

In three cases, echocardiography was performed, and in one case, an ICD (cardioverter defibrillator) was implanted. In the second case, the patient was referred for coronary artery bypass grafting and underwent surgery for three vessels. Conversely, in the third case, the patient refused surgery and instead underwent right and descending anterior stenting in one session with two DES implants, resulting in an improvement of the patient's symptoms3, 5

The anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery is a rare occurrence, and its long-term implications warrant careful consideration. Given the unique challenges posed by this anomaly, we recommend a comprehensive approach to patient care.7 Regular imaging (CT angiography or MRI) should monitor stenosis progression, while lifestyle modifications (smoking cessation, blood pressure control, lipid management) play a crucial role. Medication adherence (antiplatelet therapy, statins) and scheduled follow-up visits are essential. Educating patients about symptoms and risk factors is vital for ongoing management.8

A comparative analysis with similar cases reported in the literature highlights the significance of the findings in our case. For example, Angelini et al. examined 1950 patients with coronary anomalies and found that the incidence of the left main coronary artery originating from the right sinus of Valsalva was associated with a 6% occurrence rate of sudden cardiac death, particularly among young athletes.9 Our case involved a 51-year-old man with a significant smoking history who presented with chest pain and was found to have an anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva, similar to the cohort studied by Brothers et al., which emphasized the high-risk of myocardial ischemia and sudden death in patients with this anomaly, even without the course between great vessels.10

In terms of management, our patient refused coronary artery bypass grafting and instead underwent successful stenting of the right and descending anterior arteries with drug-eluting stents, resulting in excellent outcomes.11 However, stenting remains an effective intervention for patients not suitable for surgery.12

Patient education and counseling are crucial in managing such anomalies. In our case, comprehensive discussions about the anomaly's significance and potential risks were essential, especially as the patient declined surgery. Ensuring the patient understood the rationale behind treatment decisions was critical for informed decision-making. Monitoring the patient's cardiac health during follow-up visits includes regular imaging (CT angiography or MRI) to assess stent patency and cardiac function, blood pressure monitoring, lipid profile assessments, and adherence to prescribed medications. Follow-up visits every 6 months are recommended to evaluate the patient's condition and adjust the treatment plan as necessary.

In summary, coronary anomalies are rare but potentially serious and have been extensively studied using anatomically-based classification systems. The anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery originating from the right sinus of Valsalva is among the potentially serious coronary anomalies and has been associated with sudden death in young, athletic males. Anatomically-based classification systems encompass all possible anatomical variations, regardless of whether or not they have been previously reported. In some cases, surgery may be necessary, but other cases may respond to stenting or other interventions.

In our case, the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of the patient with an anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery presented unique challenges. Due to the tortuous course of the vessel, standard angiographic views were suboptimal, and precise catheterization was required. Balancing the risk of complications with achieving adequate stent expansion during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was crucial. Despite the severity of stenosis, the patient declined surgical intervention, emphasizing the need for alternative strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jamal Ataya: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; visualization; writing – original draft. Boushra Alkhattab: Conceptualization; methodology; visualization; writing – original draft. Nabeha Haytham Alibrahim: Conceptualization; methodology; visualization; writing – original draft. Somar Shalaby: Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing – original draft.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was also taken from the Faculty of Medicine at Damascus University—AlAssadi Hospital University.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.