Ovarian Dysgerminoma Associated With Pregnancy Presenting as Hemoperitoneum: An Obstetric Case Report

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Ovarian dysgerminomas are malignant tumors that are infrequently associated with pregnancy. These tumors are typically detected in cases of abdominal pain or during routine imaging such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging. However, we report a case of ovarian dysgerminoma in an ongoing pregnancy, discovered as a result of hemoperitoneum. A 33-year-old patient at 23 weeks of gestation presented with hemorrhagic shock and hemoperitoneum, requiring emergency surgery. During the operation, a large tumor measuring 24 × 29 cm was found in the left ovary, which was completely invaded by the mass but showed no adhesions to adjacent organs. The condition was accompanied by abundant ascites (4.5 L) mixed with blood, caused by bleeding from an ovarian vessel on the surface of the tumor. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of dysgerminoma. Haemoperitoneum is a rare but severe complication that can lead to discovering ovarian dysgerminoma. Owing to the low malignancy of this tumor, adnexectomy is an effective emergency treatment, offering favorable maternal and fetal outcomes in early-stage cases. However, larger case series are required to assess the prognosis of pregnancy associated with dysgerminoma better.

Summary

- Ovarian dysgerminoma is a rare occurrence during pregnancy and often lacks specific clinical manifestations.

- However, it may present as a severe complication such as hemoperitoneum.

- Therefore, evaluating the ovaries during pregnancy is crucial, especially using ultrasound in the first trimester, to facilitate early diagnosis of potential ovarian tumors.

1 Introduction

Dysgerminoma is a malignant ovarian tumor that is rarely associated with pregnancy [1, 2]. Physiological and anatomical changes during pregnancy, especially from the second trimester onward, often complicate diagnosis [3]. Managing dysgerminomas in pregnancy is a complex and controversial issue that requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including tumor stage, the patient's desire to conceive in the future, and gestational age [4].

Here, we present a case of ovarian dysgerminoma diagnosed during pregnancy following hemoperitoneum. This rare case highlights the diagnostic challenges, treatment options, and prognosis of ovarian dysgerminoma associated with pregnancy, as well as the unique aspects of this clinical scenario.

2 Case History/Examination

The patient was a 33-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 1, admitted as an emergency owing to a deteriorated general condition in the context of a 23-week pregnancy. She had undergone a cesarean section 3 years earlier for a placental anomaly but had no other significant medical history.

On admission to the gynecology emergency department, the patient presented in hemodynamic shock with abdominal pain (blood pressure 80/05 mmhg, pulse 115 bpm, respiratory rate 32 cpm). A 23-week pregnancy with fetal cardiac activity of 132 bpm was confirmed. Clinical examination revealed abdominal fluid accumulation (positive Flot's sign) that had been developing for 10 days.

3 Methods

3.1 Differential Diagnosis, Investigation, and Treatment

Differential diagnoses included an abdominal or ovarian pregnancy. An ultrasound performed a week prior at a primary care facility had confirmed a 23-week intrauterine mono-fetal pregnancy with fetal cardiac activity. However, the ovaries were not visualized, and neither ascites nor an ovarian mass was detected. Given these limitations and ongoing diagnostic uncertainty, the patient was referred to a tertiary center with advanced diagnostic capabilities. Her condition worsened within the same week.

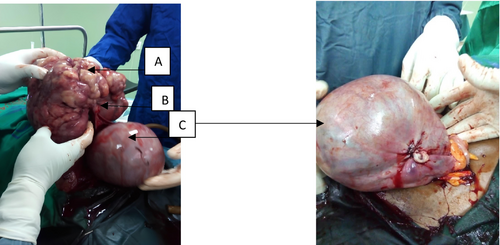

Therefore, an exploratory laparotomy was indicated. The emergency preoperative work-up revealed a hemoglobin level of 8.9 g/dL. Renal and other preoperative tests were normal (urea 0.18 g/L, creatinine 8 mg/L, blood glucose 0.85 g/L, prothrombin 97%). The patient was stabilized with two peripheral venous lines and infusion of macromolecules. Oxygen was supplied at a rate of 6 L/min via nasal mask. Intraoperatively, 4.5 L of blood-stained ascites were drained upon coeliotomy. The gravid uterus appeared normal; however, a large budding ovarian tumor of the left ovary measuring 24 × 29 cm (Figures 1 and 2), with bleeding on the surface of the tumor, was discovered. This tumor invaded the entire left ovary without adhesions to neighboring organs. A left adnexectomy was performed, which involved surgical removal of the fallopian tube and ovarian tumor. The left lumbo-ovarian ligament was ligated with absorbable sutures and sectioned. The anterior wall of the abdomen was closed plane by plane with absorbable sutures. The skin was stitched with absorbable sutures. The estimated intraoperative blood loss was 230 mL, though precise quantification was challenging owing to the mixing of blood and ascitic fluid. Postoperative management included intravenous phloroglucinol, analgesics (paracetamol), an antibiotic (amoxicillin for 7 days) and 200 mg of progesterone administered vaginally for 10 days to prevent threatened abortion.

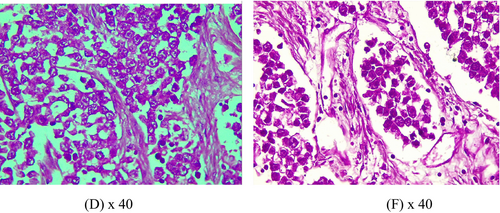

A macroscopic examination of the tumor revealed a solid, gray–white, lobulated mass without cystic components. Histological analysis confirmed ovarian dysgerminoma (Figure 3), characterized by malignant proliferation of polygonal cell nests with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cytological analysis of the ascitic fluid showed no malignant cells. Further staging via computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging concluded a stage Ia ovarian dysgerminoma, based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics classification. Treatment was limited to surgery with no need for chemotherapy given the absence of risk factors.

The pregnancy progressed normally, and an elective cesarean section at 37 weeks resulted in the delivery of a healthy newborn weighing 2600 g. The patient remained symptom-free during follow-up visits, which extended to 11 months after the adnexectomy and 6 months postpartum. Clinical monitoring, alpha-fetoprotein, and gonadotropin hormone assays returned to normal. The patient gave her informed consent for the management and scientific communication of her case.

4 Discussion

Germ cell tumors account for 3%–5% of malignant ovarian tumors, with dysgerminomas being the most common types [5, 6]. Their incidence during pregnancy is estimated to range between 0.2 to 1 per 100,000 pregnancies [4]. Dysgerminomas primarily occur in young women of reproductive age, often around 30 years [2, 7, 8]. The association of a dysgerminoma and pregnancy is rare [9], making this case noteworthy, particularly as it was discovered in the context of a hemoperitoneum. This rarity is compounded by the diagnostic challenges during pregnancy [3]. Pathophysiologically, dysgerminoma is a neoplasia of the primordial germ cell that has not yet acquired its potential for differentiation. Cytogenetic studies are certainly needed to understand the malignant transformation of these undifferentiated germ cells.

Early prenatal consultations play a pivotal role in detecting adnexal pathologies and identifying associated risks. Ovarian tumors, often asymptomatic, may initially present as an adnexal mass detected during abdominal or vaginal examination [8, 10]. During the first trimester, palpation may reveal a groove between the uterus and the adnexal mass, a feature more challenging to identify in later pregnancy stages because of anatomical changes. In contrast, physiological examination is much more difficult during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, as the volume of the uterus changes the anatomy of the pelvic organs. The ovaries remain pelvic, whereas the uterus becomes abdominopelvic, concealing the ovaries on abdominal palpation. Moreover, the groove between the uterus and the ovarian tumor may be lost, resembling a single organ during vaginal palpation. Similarly, ultrasound assessment faces limitations.

Malignant tumors, such as dysgerminoma, are characterized by abnormal neovascularization. The most frequent sign of the association between ovarian tumors and pregnancy is abdominal pain [7, 11]. In our case, ovarian dysgerminoma was discovered intraoperatively in a state of shock. The exact mechanism of hemorrhage in dysgerminomas associated with pregnancy is unknown. However, we speculate that the neovascularized state of the dysgerminoma, combined with the fragility of blood vessels induced by pregnancy, contributed to tumor hemorrhage, explaining why the ascitic fluid case was blood-tinged. In contrast, some authors have suggested that pregnancy may act as a protective factor against the development of ovarian malignancies [12].

In the first trimester of pregnancy, examining the adnexa is essential, particularly during ultrasound, to visualize the gravid corpus luteum and identify abnormalities such as masses. Certain sonographic criteria should raise suspicion of malignancy: a size greater than 6 cm, morphological features (multilocular cysts, solid components, poorly defined contours, thick walls > 3 mm), heterogeneity, presence of vegetations, and central vascularization on Doppler with a resistance index < 0.4 [13]. In our case, the ultrasound did not reveal or describe the tumor. Youssef et al. reported a case where an early ultrasound performed at 10 weeks under favorable conditions successfully diagnosed an ovarian dysgerminoma [14]. When ultrasound findings are inconclusive, magnetic resonance imaging may help clarify the diagnosis of ovarian tumors. A pelvic CT scan is generally contraindicated during pregnancy; however, a thoracic CT scan with a pelvic focus may be used to assess the extension of an advanced tumor. Diagnostic laparoscopy remains a valuable alternative when imaging is limited [14].

The tumor marker CA 125 is not useful for diagnosing ovarian dysgerminoma during the first trimester of pregnancy, as it is physiologically elevated during this period. However, CA 125 decreases in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and can be used for follow-up [13]. Owing to the urgent nature of managing our case, a CA 125 assay was not performed. Similarly, the CT scan was conducted postoperatively to assess tumor extension.

The management of dysgerminomas associated with pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary approach involving an oncologist, obstetrician, anaesthesiologist, and neonatalogist [3, 8]. Laparoscopy may be used for peritoneal cytology, and unilateral adnexectomy can provide a precise histological diagnosis and inform the therapeutic strategy when operative emergencies are absent [15]. In our emergency case, characterized by hemorrhagic shock, multidisciplinary consultation was not possible, and unilateral adnexectomy sufficed [16]. Preservation of the healthy contralateral ovary is essential for maintaining the patient's fertility [6, 8, 17]. Considerations for further management include histological type, disease stage, pregnancy term, and the patient's preferences. Litzka et al. reported a case of dysgerminoma during pregnancy where chemotherapy was deferred until after cesarean section at 34 weeks gestation to optimize neonatal survival, with complete remission achieved up to 16 months later [1]. The prognosis of these ovarian tumors discovered during pregnancy appears relatively favorable. However, definitive conclusions remain limited owing to low-quality evidence from case reports and small series.

Maternal prognosis depends on the stage at diagnosis. In our case, being at stage Ia, the outcome was favorable, with adnexectomy alone being sufficient. This observation aligns with reports by other authors [9, 18-20]. Regarding the mechanism of dysgerminoma rupture and hemoperitoneum, we hypothesize that the large size of the tumor and pressure exerted by the gravid uterus contributed to its rupture. Similar cases have demonstrated favorable fetal outcomes attributed to early surgical management before tumor rupture [4, 5, 20]. Although transplacental transmission of neoplasm is rare in ovarian germinomas, there are potential risks, including miscarriage, preterm delivery, and complications associated with treatment, such as the teratogenic effects of chemotherapy. Long-term studies of affected newborns are necessary to draw more robust conclusions.

5 Conclusion

We report a case of ovarian dysgerminoma associated with progressive pregnancy. This dysgerminoma was asymptomatic and discovered during a rare and severe complication: hemoperitoneum caused by the rupture of a blood vessel above the tumor. This rupture was likely due to the large size of the tumor and the pressure exerted by the gravid uterus, representing the primary clinical implication of this case. Given the low malignancy of the tumor, adnexectomy was an effective emergency treatment, offering favorable maternal and fetal outcomes in the medium term for early-stage disease. However, larger case series are required to assess the prognosis of pregnancy-associated dysgerminoma. Additionally, developing more sensitive diagnostic protocols for detecting ovarian tumors during pregnancy could facilitate early diagnosis and prevent complications.

Author Contributions

Eléonore Gbary-Lagaud: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. José Loba: data curation, methodology. Ramata Kouakou-Kouraogo: investigation, software. Carine Houphouet-Mwandji: investigation, software. Roland Adjoby: supervision, writing – review and editing.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [repository name, e.g., “figshare”] at [doi], reference number [reference number].