Early Detection and One-Year Follow-Up of Subclavian Steal Syndrome Treated With Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Case Report

Funding: This work was supported by the Taipei Veterans General Hospital Hsinchu Branch (Grant No. 2024-VHCT-RD-P011).

ABSTRACT

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) often goes undiagnosed because of its variable and subtle symptoms, highlighting the need for innovative diagnostic approaches. This case report explores the integration of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in both diagnosing and managing SSS, marking a pioneering contribution to the field. An 80-year-old woman with persistent dizziness, unresponsive to conventional treatments, underwent TCM pulse diagnosis, which revealed significant inter-arm pulse discrepancies. Subsequent Western imaging confirmed SSS. The patient was treated with Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) targeting Qi deficiency and blood stasis, resulting in significant symptom improvement and a reduction in inter-arm systolic blood pressure disparities. Follow-up over 1 year showed sustained benefits. The integration of TCM pulse diagnosis, CHMs, and Western imaging highlights their complementary roles and potential as adjunctive therapies for managing SSS, offering a novel and comprehensive therapeutic strategy.

Summary

- Early diagnosis of subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) is crucial.

- This case demonstrates the potential of integrating traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Western imaging for effective diagnosis and treatment, leading to significant symptom improvement and sustained benefits.

1 Introduction

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) arises when blockage or narrowing occurs in the subclavian artery proximal to the vertebral artery, causing insufficient blood flow to the ipsilateral arm and resulting in reduced blood pressure (BP) in that arm. Retrograde blood flow from the contralateral vertebral artery may supply the basilar artery, sometimes diverting blood away from the brainstem. When symptoms of cerebral ischemia, such as dizziness, occur because of reduced blood flow in the vertebrobasilar system, the condition is diagnosed as SSS [1, 2]. SSS is commonly associated with atherosclerosis, often evidenced by a notable BP difference between the right and left arms. The pulse in the affected arm may be absent or significantly weaker than in the contralateral arm [1]. This condition is typically caused by obstruction or narrowing of the subclavian artery, most often on the left side, with a difference in brachial systolic blood pressure (SBP) of over 20 mmHg between the affected and unaffected arms serving as an indicative marker [3].

For diagnosis, initial screening involves measuring BP in both upper extremities, followed by Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography to confirm subclavian artery stenosis or obstruction. Although many patients are asymptomatic and can be managed conservatively with antithrombotic therapy, glycemic and lipid control, and regular imaging [2, 4], symptomatic patients may experience dizziness, double vision, tinnitus, and hearing loss [5]. In cases with a marked BP difference between arms (> 40 mmHg), endovascular stenting may be recommended [6]. Despite significant advances in the understanding and management of SSS, the role of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in diagnosing and managing this condition remains largely unexplored. This report uniquely examines the integration of TCM in both the diagnosis and treatment of SSS, a condition traditionally managed with Western medical practices.

2 Case Presentation

2.1 Presenting Complaints and Disease History

An 80-year-old female patient with a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerotic heart disease was under regular follow-up at a cardiology outpatient clinic. Her current medication regimen includes amlodipine 5 mg and atorvastatin 10 mg (Caduet) twice daily, metformin 50 mg and vildagliptin 500 mg (Galvus) twice daily, and acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg (Aspirin) once daily. The patient denies experiencing any symptoms suggestive of transient cerebral ischemia, such as limb numbness, paralysis, or visual disturbances, over the past 10 years. However, for the past 2 years, she has reported recurrent dizziness, bilateral tinnitus, hearing impairment, and headaches. Despite multiple consultations with cardiology, otorhinolaryngology, and neurology specialists between 2017 and 2018, she was diagnosed with central vertigo and prescribed piracetam 1200 mg (Nootropil) once daily as a cerebral circulatory enhancer, which offered minimal symptom relief.

2.2 Traditional Chinese Medicine Consultation

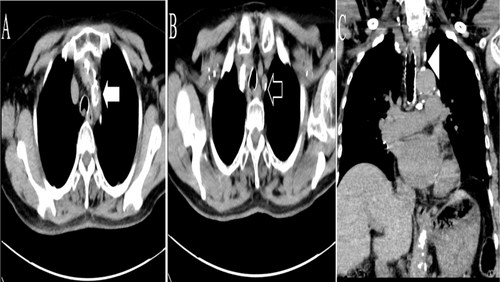

In December 2018, the patient sought a consultation at a TCM outpatient clinic due to persistent symptoms. TCM pulse diagnosis revealed a slippery pulse on the right hand and a weak pulse on the left. BP measurements indicated a significant SBP discrepancy of 53 mmHg between her right and left arms, raising suspicion of SSS. Further evaluation was advised, and a chest CTA performed on December 26, 2018, confirmed stenosis of the left subclavian artery due to atherosclerosis, thus diagnosing SSS (Figure 1). The TCM practitioner recommended a treatment plan focusing on tonifying Qi and addressing blood stasis. Due to her advanced age, the patient declined endovascular stenting and opted for conservative management. She returned to the TCM clinic on January 3, 2019, to begin ongoing treatment, which continued for ~1 year.

2.3 Neurologic Diagnosis

Other transient cerebral ischaemic attacks and related syndromes (SSS): International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10): G45.8 [7].

2.4 Therapeutic Intervention

The patient attended a total of 16 visits from December 2018 to July 2020. BP measurements throughout the treatment period are documented in Table 1. During the initial eight visits (December 2018 to March 2019), she reported persistent symptoms, including dizziness, tinnitus, and hearing loss. The TCM practitioner focused on tonifying Qi and benefiting the kidney as the primary treatment strategy, prescribing the following Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) in powder form, referred to as Group A: Yi-Qi-Cong-Ming-Tang 4 g, Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan 4 g, Yuan-Zhi (Radix Polygalae) 1 g, and Shi-Chang-Pu (Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii) 1 g, with a dosage of 5 g taken twice daily. However, after 2 months of therapy, the patient experienced minimal improvement in symptoms, and no substantial change in BP was observed between the arms, leading to a temporary interruption in TCM consultations.

| Visit | CHMs Group A treatment period (n = 8)a | Visit | CHMs Group B treatment period (n = 8)b | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right brachial BP (mmHg) | Left brachial BP (mmHg) | SBP difference (mmHg) | Right brachial BP (mmHg) | Left brachial BP (mmHg) | SBP difference (mmHg) | |||

| 1 | 134/68 | 75/57 | 59 | 9 | 132/62 | 79/63 | 53 | 0.008** |

| 2 | 151/70 | 84/65 | 67 | 10 | 130/68 | 86/67 | 44 | |

| 3 | 141/69 | 78/61 | 63 | 11 | 127/77 | 69/54 | 58 | |

| 4 | 136/64 | 73/58 | 63 | 12 | 124/62 | 69/54 | 58 | |

| 5 | 139/71 | 73/58 | 64 | 13 | 124/62 | 82/62 | 42 | |

| 6 | 152/68 | 87/69 | 65 | 14 | 127/77 | 89/58 | 38 | |

| 7 | 142/69 | 90/68 | 52 | 15 | 131/63 | 78/56 | 53 | |

| 8 | 150/70 | 78/63 | 72 | 16 | 126/66 | 78/60 | 48 | |

| M | 63.13 | M | 49.13 | |||||

| SD | 5.84 | SD | 7.30 | |||||

- Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CHMs, Chinese herbal medicines; M, mean; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

- a CHMs Group A: Yi-Qi-Cong-Ming-Tang, Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan, Yuan-Zhi (Radix Polygalae), and Shi-Chang-Pu (Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii).

- b CHMs Group B: Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu-Tang, Zhi-Gan-Cao-Tang, Shan-Zha (Fructus Crataegi), and Jue-Ming-Zhi (Semen Cassiae).

- ** p < 0.01 indicates statistical significance (paired sample t-test).

Due to recurring dizziness, the patient returned to the TCM outpatient clinic in December 2019 for additional follow-up visits (ninth through sixteenth sessions). Based on findings of a weak pulse in the left hand and imaging evidence of subclavian artery stenosis, the TCM practitioner adjusted the treatment protocol to address Qi deficiency and blood stasis. The patient was prescribed a modified herbal powder formulation, Group B, containing: Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu-Tang 3 g, Zhi-Gan-Cao-Tang 4 g, Shan-Zha (Fructus Crataegi) 1.6 g, and Jue-Ming-Zhi (Semen Cassiae) 1.4 g, with a dosage of 5 g taken twice daily for 8 months. This adjustment resulted in a significant decrease in the patient's dizziness. Table 2 lists the herbal ingredients and their effects.

| Ingredients. Pin-Yin name (pharmaceutical name) [8] | Effects of herbs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHMs A |

Herbal Formula Yi-Qi-Cong-Ming-Tang |

Huang-Qi (Radix Astragali), Gan-Cao (Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma), Ren-Shen (Radix Ginseng), Sheng-Ma (Rhizoma Cimicifugae), Ge-Gen (Radix Puerariae), Man-Jing-Zi (Fructus Viticis), Bai-Shao (Radix Paeoniae Alba), Huang-Bo (Cortex Phellodendri) | Dizziness due to Qi and blood deficiency [9]. |

| Liu-Wei-Di-Huang-Wan | Shu-Di-Huang (Radix Rehmanniae Preparata), Shan-Zhu-Yu (Fructus Corni), Shan-Yao (Rhizoma Dioscoreae), Ze-Xie (Rhizoma Alismatis), Mu-Dan-Pi (Cortex Moutan Radicis), Fu-Ling (Poria) | Dizziness caused by deficiency of the liver and kidney [8]. | |

| Single herb | |||

| Yuan-Zhi (Radix Polygalae) | Radix Ginseng, Radix Polygalae, Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii, and Poria form Kaixin San to treat depression and dizziness [10]. | ||

| Shi-Chang-Pu (Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii) | Treatment of dizziness, headaches and deafness [11]. | ||

| CHMs B |

Herbal Formula Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu-Tang |

Dang-Gui (Radix Angelicae Sinensis), Sheng-Di-Huang (Radix Rehmanniae), Tao-Ren (Semen Persicae), Hong-Hua (Flos Carthami), Zhi-Ke (Fructus Aurantii Immaturus), Chi-Shao (Radix Paeoniae Rubra), Chai-Hu (Radix Bupleuri), Gan-Cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae), Jie-Geng (Radix Platycodi), Chuan-Xiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong), Niu-Xi (Radix Cyathulae) | Activate blood circulation and improve blood stasis [12]. Treating atherosclerosis and hyperlipidemia [13]. |

| Zhi-Gan-Cao-Tang | Zhi-Gan-Cao (Radix Glycyrrhizae Praeparata), Sheng-Jiang (Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens), Gui-Zhi (Ramulus Cinnamomi), Ren-Shen (Radix Ginseng), Sheng-Di-Huang (Radix Rehmanniae), A-Jiao (Colla Corii Asini), Mai-Men-Dong (Radix Ophiopogonis), Huo-Ma-Ren (Semen Cannabis), Da-Zao (Fructus Jujubae) | Commonly used in Taiwan to treat ischemic heart disease. Can tonify the Qi and promote blood circulation [12, 14]. | |

| Single herb | |||

| Shan-Zha (Fructus Crataegi) | In Taiwan, the most often used single herb for treating hyperlipemia and atherosclerosis [15, 16]. | ||

| Jue-Ming-Zhi (Semen Cassiae) | Treatment of hyperlipidemia, prevention of atherosclerotic plaque formation [17]. |

- Abbreviation: CHMs, Chinese herbal medicines.

2.5 Follow-Up and Outcome

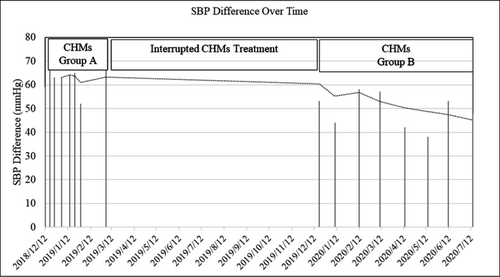

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant reduction in the SBP difference between the right and left arms, with a paired sample t-test indicating statistical significance (p = 0.008). This result underscores the potential effectiveness of TCM in alleviating SSS symptoms. Additionally, the moving average trendline in Figure 2 demonstrates that there was no change in bilateral BP during the CHMs Group A treatment, whereas a steady decline was observed during the CHMs Group B treatment. This finding suggests that the herbs targeting Qi deficiency and blood stasis (Group B) may hold promise in treating SSS.

3 Discussion

This case study underscores the innovative potential of integrating TCM diagnostic tools, particularly pulse diagnosis, with Western medical diagnostics for the early detection and management of SSS. Due to limited clinical time, routine bilateral blood BP monitoring is often overlooked, leading to delayed diagnoses of conditions such as SSS. This patient experienced significant dizziness over 2 years, consulting multiple specialists without receiving a definitive diagnosis. The breakthrough came through TCM pulse diagnosis, which revealed a critical BP discrepancy and prompted further investigation.

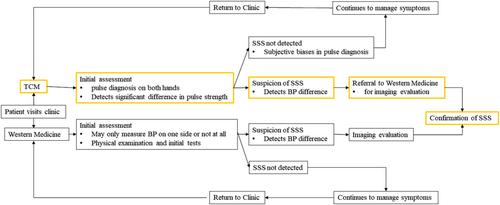

Pulse diagnosis, a fundamental technique in TCM, involves assessing the radial artery's pulsation, rhythm, and strength (as shown in Figure 3) [18-20]. In this case, a significant disparity in pulse strength between the hands was detected—a slippery pulse on the right, indicating good blood flow, and a weak pulse on the left, suggesting diminished circulation. This finding facilitated timely imaging studies, confirming left subclavian artery stenosis. Figure 4 illustrates the flowchart for early detection of SSS using TCM pulse diagnosis, one of the key reasons for presenting this case study.

Addressing Qi deficiency and blood stasis with CHMs not only helped confirm the diagnosis but also contributed to long-term management. Given the association between brachial systolic BP differences and SSS severity [3], our therapeutic aim was to reduce this disparity. Over time, the patient reported improvements in dizziness, and the BP disparity significantly decreased, suggesting the potential efficacy of CHMs in managing SSS. The condition aligns with TCM categories of Qi deficiency and blood stasis, which are associated with circulatory disorders, thrombosis, or infarction [21]. Despite the promising results, this study has limitations, including its single-case nature and the subjective nature of pulse diagnosis. The absence of objective measures, such as the Dizziness Handicap Inventory and follow-up imaging such as CTA, limits the evaluation of long-term vascular changes. These limitations highlight the need for larger, controlled studies to validate these findings.

4 Conclusion

The integration of TCM, exemplified by pulse diagnosis, offers a novel diagnostic and therapeutic pathway for SSS, complementing Western medical practices. This case demonstrates how CHMs may alleviate symptoms and reduce systolic BP disparities, positioning TCM as a potential adjunctive therapy in vascular health. However, further controlled studies with larger sample sizes and objective diagnostic tools are necessary to confirm these preliminary findings and explore broader applications of TCM in vascular conditions.

Author Contributions

Wen-Chieh Yang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital Hsinchu Branch (Grant No. 2024-VHCT-RD-P011).

Ethics Statement

As a single-case report with the patient's signed consent, no other ethical review was required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article are available upon request from the authors.