Association of Slender Patent Ductus Arteriosus Combined With PFO Related to the Transient Ischemic Attack: A Rare Case Report

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

It was a rare case of a 52-year-old female with a slender PDA combined with PFO related to a transient ischemic attack that did not improve with aspirin and/or clopidogrel treatment. We closed the PDA using the ADO-II occluder and closed the PFO with the occluder, resulting in symptom resolution.

1 Introduction

Both patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and patent foramen ovale (PFO) are common congenital heart diseases. PDA occurs when the ductus arteriosus, a blood vessel that normally connects the pulmonary artery to the aorta during fetal life to bypass the non-functional lungs, fails to close after birth. This results in an abnormal shunting of blood from the aorta to the pulmonary artery, leading to increased blood flow and pressure in the lungs. Conversely, PFO represents a persistent opening in the interatrial septum, allowing blood to flow between the right and left atriums, which is typically harmless but can cause complications in certain circumstances such as a transient ischemic attack (TIA). The TIA, also known as a mini-stroke, is a temporary episode of neurological dysfunction caused by a reduction in blood flow to the brain, often due to a blood clot or embolus. The PFO provides a direct communication between the systemic and pulmonary circulations, which could allow a clot formed in the pulmonary circulation to cross into the systemic circulation and reach the brain, causing a TIA. Adding complexity to this case, the patient also harbors a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC). However, it is extremely rare that a long tubular PDA combines with PFO. Given the rarity of this combination of anomalies and their association with a TIA, this case provides a unique opportunity to explore the interplay between congenital heart defects and cerebrovascular events, ensuring that patients receive appropriate interventions to prevent future neurological events and optimize their overall cardiovascular health.

2 Case History/Examination

A 52-year-old female patient presented with episodic dizziness for four months, accompanied by a sensation of self-rotation. She experienced episodes of dizziness several times a day or at intervals of a few days. The duration of episodic dizziness ranged from a few minutes to over 10 min.

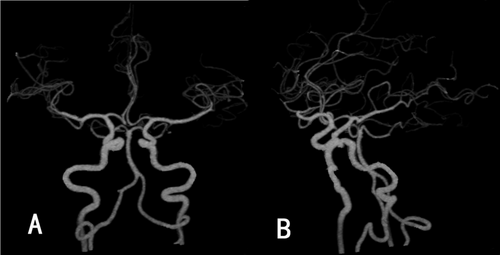

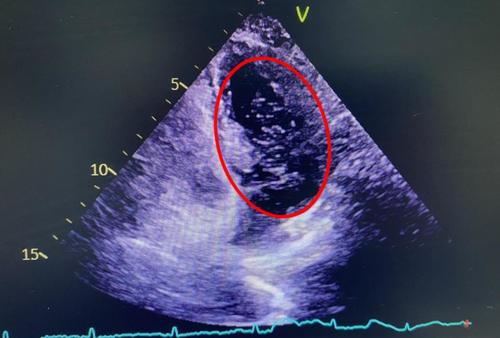

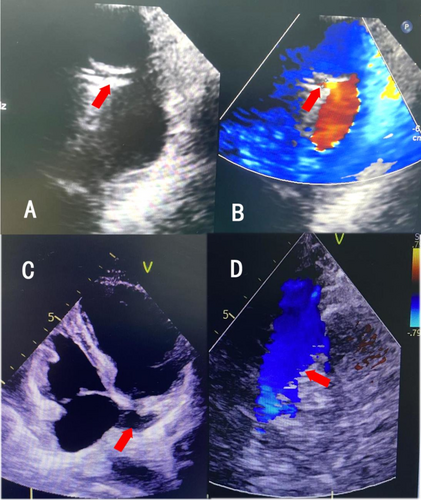

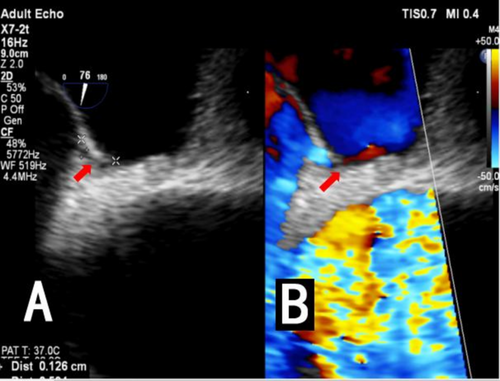

An intracranial artery CTA examination was conducted at our hospital, revealing no stenosis, infarction, or subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figure 1A,B). Therefore, the patient was considered to have a TIA and was treated with medications such as aspirin and atorvastatin. Symptoms began to improve after one week, but worsened three weeks later, with attacks becoming more frequent. The contrast right heart echocardiography demonstrated a significant presence of microbubbles in the left atrium and ventricle during the first cardiac cycle following an effective Valsalva maneuver (Figure 2). Consequently, we began to consider the possibility that the patient's vertigo symptoms might be associated with the PFO. Surprisingly, we auscultated a systolic murmur with a blowing quality at the second intercostal space along the left sternal border in the patient. The transthoracic echocardiography revealed a tubular structure with an inner diameter of approximately 2.7 mm and a length of approximately 17.5 mm, located between the left pulmonary artery and the descending aorta. Another abnormal finding on echocardiography was a persistent left superior vena cava connecting to the enlarged coronary sinus (Figure 3A–D). Upon the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) examination, an oblique septal defect was identified in the interatrial septum, with a resting oblique separation of approximately 0.5 mm and an effective Valsalva maneuver increasing the separation to about 1.3 mm. Small-volume shunt flow from the left atrium to the right atrium was also observed (Figure 4A,B).

3 Investigations and Treatment

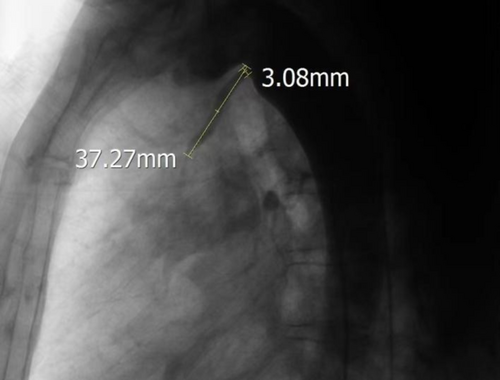

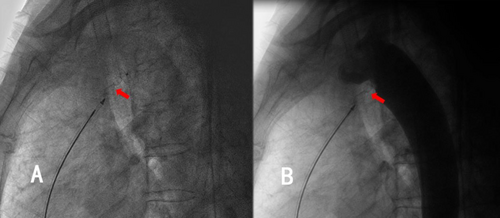

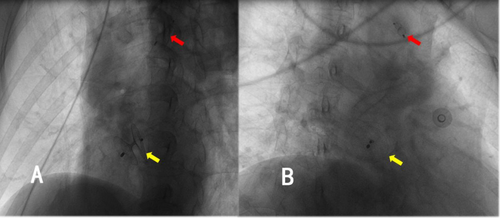

Thoracic aortic angiography revealed a rare, elongated ductus arteriosus, measuring 37.27 mm in length, with an aortic-side entry approximately 3.08 mm in diameter (Figure 5). A 6/6-mm second-generation Amplatzer ductal occluder II (ADOII) (Abbott vascular, Abbott Park, IL, USA) was used to close the ductus arteriosus. The terminal portion of the ductus arteriosus, which connected to the pulmonary artery, was markedly stenotic. This anatomy was too difficult to be antegradely approached, so the PDA was closed by building a femoral artery–PDA–pulmonary artery–moral vein wire track. Along this track, the delivery sheath was advanced through the femoral vein into the descending aorta, with its distal end positioned near the diaphragm. With the delivery sheath stabilized, a 6/6-mm ADO-II occluder was advanced along it into the descending aorta and deployed with the aortic disk released. Subsequently, the occluder and delivery sheath were simultaneously withdrawn toward the ductus arteriosus. Upon the distal end of the delivery sheath entering the ductus arteriosus and the deployed aortic disk engaging at the aortic orifice of the ductus, the withdrawal of the wire connecting to the occluder was immediately halted. Subsequently, the withdrawal of the delivery sheath was continued until both the waist and the pulmonary disk of the occluder were embedded within the elongated ductus arteriosus (Figure 6A,B). After confirming the appropriate position of the occluder within the arterial duct via aortic angiography, the steel cable was disconnected. Finally, a 26/26-mm occluder (Beijing Bairen Medical Technology Co. Ltd.) was utilized to close PFO (Figure 7A,B). The persistent left superior vena cava draining into the coronary sinus did not induce any pathophysiological changes, thus necessitating no treatment.

4 Outcome

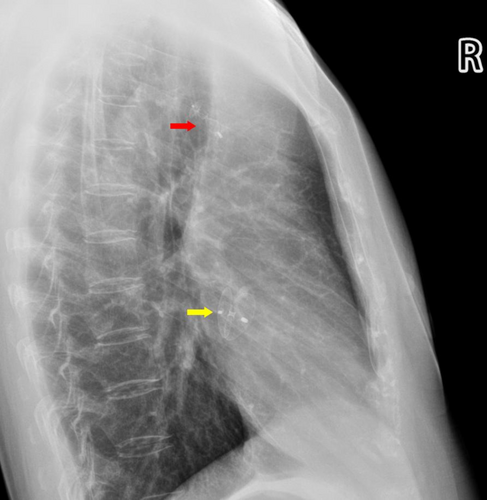

After a three-month follow-up, the patient's symptoms of dizziness and visual rotation gradually improved. Chest radiography demonstrated that both occluders were in their appropriate positions (Figure 8), and transthoracic echocardiography revealed no flow between the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

5 Discussion

The presented case involves a 52-year-old female patient who experienced episodic dizziness accompanied by a sensation of self-rotation over a four-month period. Initial diagnostic workup, including an intracranial artery CTA, failed to identify any neurological abnormalities, leading to a diagnosis of TIA. Subsequent use of contrast right heart echocardiography following an effective Valsalva maneuver was pivotal in identifying the presence of microbubbles in the left atrium and ventricle, suggesting a PFO. This finding, coupled with the auscultation of a systolic murmur and the subsequent transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic evaluations, revealed the presence of an slender PDA and a persistent left superior vena cava draining into the enlarged coronary sinus. The coexistence of a PDA and a PFO, along with a persistent left superior vena cava, is relatively rare. In most cases of TIA or stroke, the focus is often on identifying and managing vascular stenosis, infarction, or hemorrhage. This case underscores the importance of considering congenital heart defects in the differential diagnosis of neurological symptoms, particularly in patients without a clear history of cerebrovascular disease.

The American Heart Association recommends that all PDA should be closed, including the clinically silent type of PDA, which carries the risk of infective endocarditis [1]. The disks at both ends of the ADO-II serve a fixing function, thereby reducing the support requirements for its waist structure. The maximum waist diameter of ADO-II is 6 mm. When used for closing a PDA with a diameter greater than 5 mm, the waist structural cannot be compressed, resulting in unstable fixation. Therefore, ADO-II is recommended for the closure of slender PDA with a diameter of 5 mm or less. In this case, angiography revealed a rare slender PDA with an inlet diameter of 3.08 mm and a length of 37.27 mm. It was extremely challenging to withdraw the pulmonary disk of ADO-II device from the ductus arteriosus into the pulmonary artery. Therefore, embedding both the pulmonary disk and the waist section within the ductus arteriosus provided sufficient support strength to stabilize the occluder. The treatment approach was technically challenging but ultimately successful. The decision to approach the PDA via a femoral artery–PDA–pulmonary artery–femoral vein wire track was necessitated by the anatomy of the PDA, which was markedly stenotic and difficult to access antegradely. This innovative approach demonstrates the importance of adaptability and technical skill in managing complex congenital heart defects. Several studies [2-5], encompassing both retrospective analyses and prospective evaluations, have revealed that the ADO-II occluder exhibits favorable therapeutic outcomes in the treatment of PDA (PDA) in premature infants or low-birth-weight neonates. These studies have demonstrated high success rates for occlusion, with no occurrence of severe complications in the patients post-occlusion. These findings provide robust support for the use of ADO-II in occluding PDAs with narrow luminal diameters.

When the right atrial pressure experiences temporarily or sustained elevation (e.g., following termination of the Valsalva maneuver, coughing, diving, etc.), small emboli in the right heart system traverse the PFO to the left heart system, subsequently entering the cerebral arterial circulation. These emboli may occlude branches of cerebral arteries, leading to focal cerebral ischemia and triggering TIA. This is what is known as anomalous embolism, and it is one of the significant causes of TIAs or ischemic strokes [6]. The probability that a PFO is causally related to the stroke can be estimated by the Risk of Paradoxical Embolism (RoPE) Score and the PFO-Associated Stroke Causal Likelihood (PASCAL) classification system [7]. For this patient, the RoPE score is 5 points (no history of hypertension (+1) or diabetes (+1), non-somker (+1) and 52-year-old (+2)), but stroke related to PFO is possible by the PASCAL classification system because the RoPE score is 5 points and a large right-to-left shunt is present. Given the patient's recurrent and high-probability TIAs, it is reasonable to consider concurrent closure PFO and PDA [8, 9].

For this case, the initial misdiagnosis highlights the need for a thorough and comprehensive diagnostic workup in patients with neurological symptoms. A single negative test should not be sufficient to rule out a potential diagnosis. In patients without clear evidence of cerebrovascular disease, congenital heart defects should be considered in the differential diagnosis. This requires a high index of suspicion and a willingness to pursue additional diagnostic testing. It is feasible and effective to close a slender PDA with ADO-II. During the 3-month follow-up period, the patient's TIA symptoms gradually improved, suggesting a positive effect of the PFO closure.

Author Contributions

Zhi Wen: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Mingwu Tian: formal analysis, methodology. Zhiqiang Huang: validation, writing – review and editing. Changxue Wu: supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Xin Wei: supervision, validation, writing – review and editing.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author's data supporting this study's findings are available upon reasonable request.